The Double Lives of Geoffrey Moss

Geoffrey Moss has led double lives since 1961.

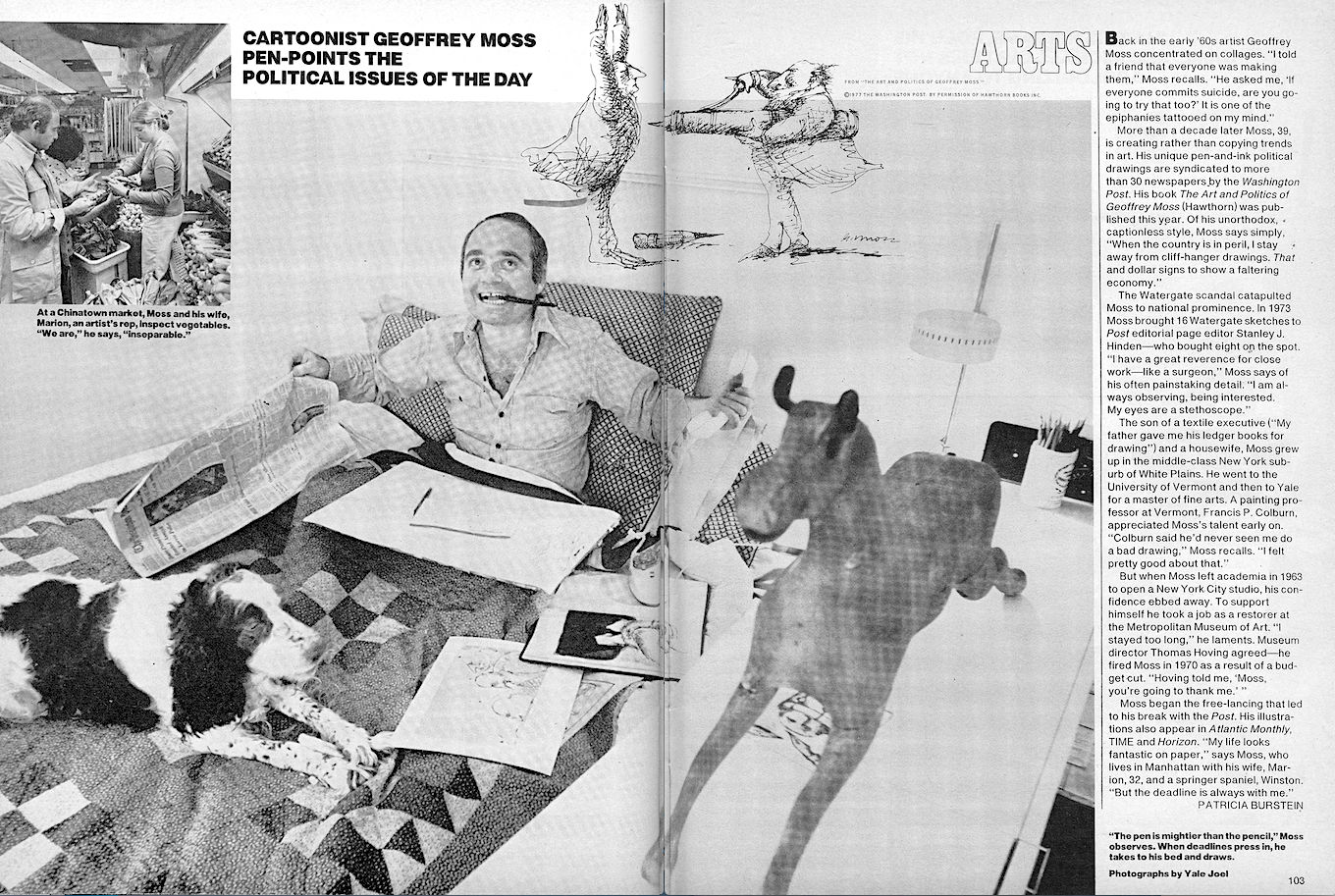

The public knows him for his instantly recognizable style of searing political cartoons that appeared in the op-ed pages of the Washington Post for decades. He was nominated two times for the Pulitzer Prize and became one of the most sought-after illustrators in the country. But during all that time — ever since 1961, when he entered Yale University’s Master of Fine Arts program — he has privately led a double life as an abstract painter.

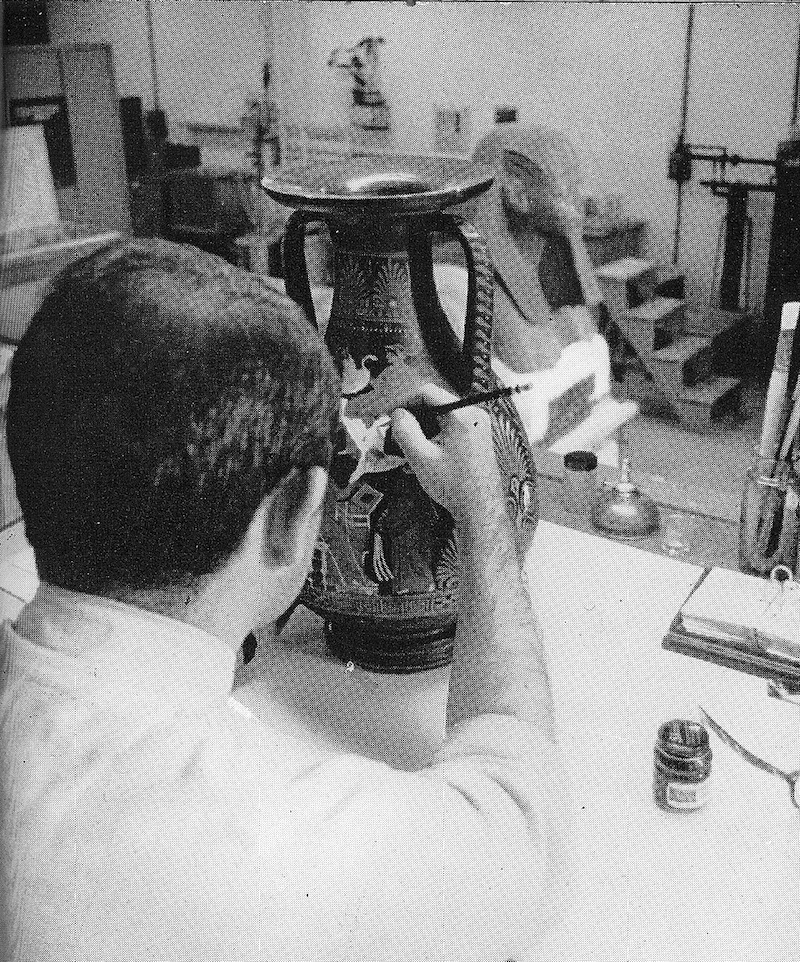

But Moss — the abstract painter — instead became a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the next eight years. There he was delighted to discover he was working with a staff composed entirely of painters. “I was an art restorer by day and a painter by night,” he says, “without having to submit myself to the vulnerability of having to peddle my work.” For the next eight years he worked primarily as a patinator, often in-painting ancient Greek vases and marveling at their compositions and colors. Thomas Hoving, then the Met’s director, even sent him traveling about Europe to learn more about art restoration techniques.

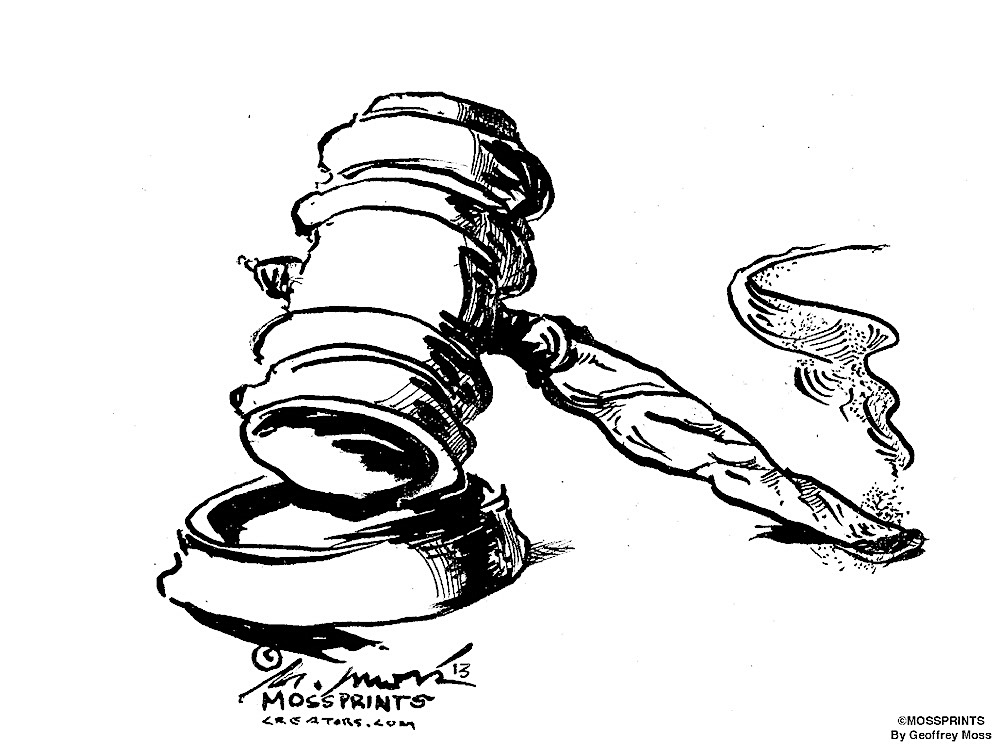

Then in 1973, he got one of those career-changing bits of advice from a classmate who was also leading double lives. His friend, a successful graphic designer, had studied under Norman Ives at Yale. But he actually became a C.I.A. agent. His inside tip for Moss was that there was good quick money in newspaper illustration, especially in the op-ed section. That year Moss sold his first political cartoon to the Washington Post — the first of hundreds. His timing was excellent, too, because when the Watergate scandal broke that summer the Nixon administration was among the first victims on his firing line. Few were spared, really. It had been one hundred years since Thomas Nast [1840–1902], the father of American political cartoons, had lambasted the corrupt Boss Tweed administration in New York. His very name was adopted as a new word, “nasty.” It was in that spirit of uncompromising morals that Dan Rather wrote the foreword to The Art and Politics of Geoffrey Moss (Washington Post, 1977). “I am addicted to his work,” he wrote. “He is a truth-seeker. And a truth-teller, specializing in tough truths…I would look at his material in the Washington Post and say to myself, ‘Hey this guy is terrific. He is on to something.’ Without a word, without so much as a single number, he hammers home truths…Moss is in another stream, one that allows him to engage in outright editorializing and satire.” Rather was referring to the fact that Moss was a pioneer who refrained from using captions to explain his satirical cartoons, depending instead upon the conceptual power of the image.

Despite his success in the world of political cartooning, by the late 1980s Moss wanted a change. Not only was it was time to focus fully on painting but he had built up a large body of work. In the process he greatly reduced his acceptance of assignments. Sure, those two Pulitzer Prize nominations were great. So was being profiled in People magazine. And in one year he even won six of the top awards from the Art Directors Club of New York. But nearly every day for decades he had steadfastly pursued abstraction. Besides, the advent of computer graphics was quickly changing conceptual thinking in illustration. To Moss, it seemed as if no one understood graphic metaphors. “All of a sudden, it seemed as if no one could think,” he said. Several universities agreed (among them M.I.T., Parsons, Syracuse, and the University of Massachusetts) and contracted him to teach innovative courses in conceptual thinking. If what he saw as the decline of illustration coincided with his turn to emphasizing painting, the death of his father provided another catalyst. At that time Moss’s good friend Brice Marden admonished, “Moss, get back to painting!” Moss recalled, “That’s when the light bulb really went on.”

But Moss had never networked with galleries. “All those years I had been seduced by my own illustrations. I had made a good living being obstinate…There had always been that pebble in my shoe, something that kept me stubbornly independent, refusing to sell out.” So when he first approached galleries his experience was predictably frustrating because he was immediately recognized as a renowned illustrator. “Illustration was the kiss of death,” says Moss. “If I had been a guard at an art museum, as many of my friends were, they would have accepted me…but not when they found out I was an illustrator.” Moss is not alone with his double lives. Throughout the 20th century a select group of highly accomplished artists were also engaged in both fine art and illustration. All felt pigeon-holed, ostracized from the fine arts galleries. This problem was first brought to light by Richard Boyle’s insightful, Double Lives: American Painters as Illustrators, 1850-1950 [New Britain Museum of American Art, 2009]. One of those more recent painters cited with a similar problem was Arthur Getz [1913-1996], the most prolific cover artist in the history of the New Yorker magazine. For his first solo exhibition of paintings at the Babcock Gallery in the 1950s he had to sign his work “Arthur Kimmig,” using his middle name to overcome this problem.

As with all kids who become artists Moss simply recalls constantly making marks. He was born in Brooklyn in 1938 and raised in White Plains, New York. He created his first abstract works by melting crayons on the radiators just to see how the colors would react. He did not recall if his mother, an artist who attended Cooper Union, was amused. The colors of comic books from the 1950s especially inform his paintings. “I was more fascinated with the colors than the stories,” he notes. Fine art came into greater focus at the University of Vermont where he was inspired by Francis Colburn [1909-1984] a painter who had turned from regionalism to surrealism, then geometric landscapes recalling John Marin. A major in American Literature and Russian History, Moss studied under the poet Winfield Townley Scott [1910-1968], also an expert on the horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. When Moss began his graduate work at Yale in 1961 color took on new meaning in Josef Alber’s course. And Alex Katz “taught painting versus rendering edges.” In 1962, Moss began his first series of abstract expressionist paintings called “The Black Series,” which deftly plumb art historical precedents from Piranesi to Seurat to Kline. Even after Moss opted out of New York’s gallery scene he remained friendly with his fellow painters. When Katz left for Skowhegan in Maine for the summers, he asked Moss to stay in his loft. There he gathered his best artist friends, Brice Marden and Al Held, and became friendly with John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

Moss is as methodical in his approach to abstraction as he has been in his political satire. Every canvas starts with pencil drawings; he then moves on to a series of increasingly larger color studies until he is ready to approach the large canvas. “I define myself as an American painter, paying attention to the essence of an idea. Painting in series, exploring the physical energy of the paint, isolating my subject. I continually return to re-examine, simplify, and abstract the essentials in my work.” Moss develops his paintings in series, typically starting with numerous studies on paper. For example, his “Inappropriate Appropriations” series is a compelling body of work that represents his most private and unseen paintings. This series uses as its reference point the classic erotica imagery of Japanese shunga painting found in ukiyo-e color woodblock prints of the 17th and 18th centuries, a subject with which he first became familiar while working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “I wanted to give this Japanese subject an American character…It’s a process of distillation in many steps” until the erotic image becomes abstracted yet still bearing a subliminal seduction. Another powerful series in abstraction is his “The Architecture of Water” — which will be revealed here soon!

— Peter Hastings Falk