We are grateful to Connie Gibbons, Director of the Mulvane Art Museum in Topkeka, Kansas, for sharing her essay, Bud Holman: A Retrospective, first published in her 2017 exhibition catalogue, which has been edited to reflect Holman’s passing in 2023.

“Whenever we enter the land, sooner or later we pick up the scent of our own histories, and when we begin to travel vertically, we end up following road maps in the marrow of our bones and in the thump of our blood.”

— William Least Heat Moon

Imagine, if you will, the life of one man told through the strokes and textures of paint, densely layered, streaming across miles of canvas. Each morning, he rose with the desert sun and with paint brush in hand, and began the ritual of dancing the world into being. Canvases that had been lined up capitulated to his strokes and slashes as he built layer upon layer of color and light, form and rhythm — the world of the towering mountains and rocks jutting from the earth, the colors of life blooming in an unforgiving desert, the memories of distant places and far off lands. The patterns and symmetry of nature and man emerge, disappear and reemerge as the artist constructs the world. This was the life of Bud Holman.

Cradled along the southernmost border of the United States, Holman’s studio was just a stone’s throw from the vertical beams that soared 18 to 20 feet high, still defining the landscape for as far as the eye can see. The fence that separates Old Nogales, Mexico, from Nogales, Arizona, stands as a monumental and sweeping barrier that forms a shuttered view of another world. Through the slatted wall, vestiges of businesses, homes, and architecture clinging to distant bluffs are revealed. Traces of lives lived just on the other side of this vertical fortification create dances of color, texture, shadow, and light that flicker in and out of view. Although his work is not political by nature, the presence of the steel barrier that separates Mexico and the United States pervades his latest works in the strong perpendicular slashes that advance across the horizon. The barrier echoes the rock formations that jut from the desert valley and define the tortured landscape.

The Sonoran Desert stretches across southern Arizona into Mexico and served as a prime source of inspiration for the artist. During his lifetime Holman explored its mountains, valleys, towering volcanic cliffs, and landscapes animated by changing seasons—it is this that sustained his studio practice for decades.

New Mexico Landscape, 1971-80 (page1); Catalina Mountains 1, 1983-85 (page 14); High Sonoran Desert Landscape,1985-92 (page 10); Baboquivari Mountains, 2000-07 (page 23); and The Tough Nut, 2012-15 (page 20), communicate the terrible beauty of the desert and give voice to its dominion. To the people of the Tohono O’odham Nation, Baboquivari is a sacred mountain and considered to be the navel of the world, the opening in the Earth from which they emerged after the world flood.The layers of paint, texture, form, and color built up over many years is a tribute to the sacredness of the landscape — the discipline of painting each day is a ritual act of consecration.

Working in pentimento, earlier images, forms, and strokes emerge from beneath new layers reminding us of their presence. Holman’s process was slow and methodical, as the viewer’s experience of it should be. We can sense his systematic and persistent layering of paint as he worked on multiple canvases at once. The result is arresting. Surfaces are so vast, so deep, the viewer is commanded to take a closer look. Simultaneous nearness and farness are conveyed in the very texture of the paint itself. The presence of previous layers fuse with later stages giving evidence to the mutability of the landscape and the ways the subject may have occurred to the painter through his process. For Holman, each canvas was a garden that was planted, grown, tilled, and replanted. Always the remnants of previous plots remain to remind us of the gardener’s changing relationship with the ground he cultivates.

Holman was first and foremost a colorist with an unflinching eye for the nuances of reflected light. His pallet belies what we think we may know of the desert’s barrenness. “Throughout the year, the desert portrays many different attitudes,” he said. A master at capturing the many moods and tones of the places that he has traversed, Holman captured a sense of the light, movement, and sacred in all of his landscapes’ many moods. Although Holman’s most recent paintings express the character of the Southwest, he did not hesitate to borrow from the exotic locations that reside in his memories. Topeka, 2013-16 (page 18); Shawnee, 2015-16 (page18); Old Nogales, Mexico, 2013-16 (above); Manitou, 2013-16 (page 21); and Lake Lucerne, 2013-16 (page 18), all pay tribute to these remembrances. More lyrical and darker than earlier works, deep greens are slashed with black marks and intersections of pinks, lavenders, and blues. These most recent works speak of the twilight hours and exist as evidence of the battles that were waged each morning as the artist painted a world of visions extracted from half seen light. At 90 years old, and slowly losing his eyesight, Holman gathered these scenes from memory, as he pursued the ritual of dance and creation. The colors and forms of landscapes where he has wandered coalesce as they reflect the reminiscences and heart of the artist’s relationship with the landscape of his life. Not so much a record of place, these works are a record of a voyage that is not complete.

From his earliest days in Topeka, Kansas, to his most recent paintings, Holman’s connection to the land has been unassailable. For Holman, the landscape encompassed many things: the physical features of a place, the quality and character of light, the peoples, traditions, stories, and cultures that exist there. In The Lure of the Local, Lucy Lippard writes that “Space defines landscape, where space combined with memory defines place.” For Holman, landscape resided in his memory and place is expressed in the moments and impressions that encompass a ninety-plus year journey.

Born in Topeka, Kansas in 1926, Bud Holman was from a family of abolitionist Presbyterian ministers from Vermont and New Hampshire. Growing up during the Great Depression, Bud Holman lived simply, attending a one-room schoolhouse. He packed himself a sandwich in the mornings, saddled his horse, and spent his days riding across open land. He found arrowheads left by Shawnee Indians who had lived and hunted on those same plains. He also collected butterflies and night-flying moths. His resourcefulness, imagination, and closeness to the earth during these formative years became his touchstones as an artist.

Bud Holman’s first glimpse of the Southwestern desert was in the early 1940s aboard the Union Pacific Railroad, gazing out the window on two-day train rides from Kansas to California, where he spent summers as a boy. Those vast, mountainous landscapes sparked something deep down, germinating in his mind’s eye for decades before they emerged on canvas.

In his early teenage years, Bud Holman spent vacations visiting cousins in Pasadena, California. The renowned landscape painter Marion Kavenaugh Wachtel, a neighbor and friend of his cousins, gave Bud Holman his first formal lessons in landscape painting.

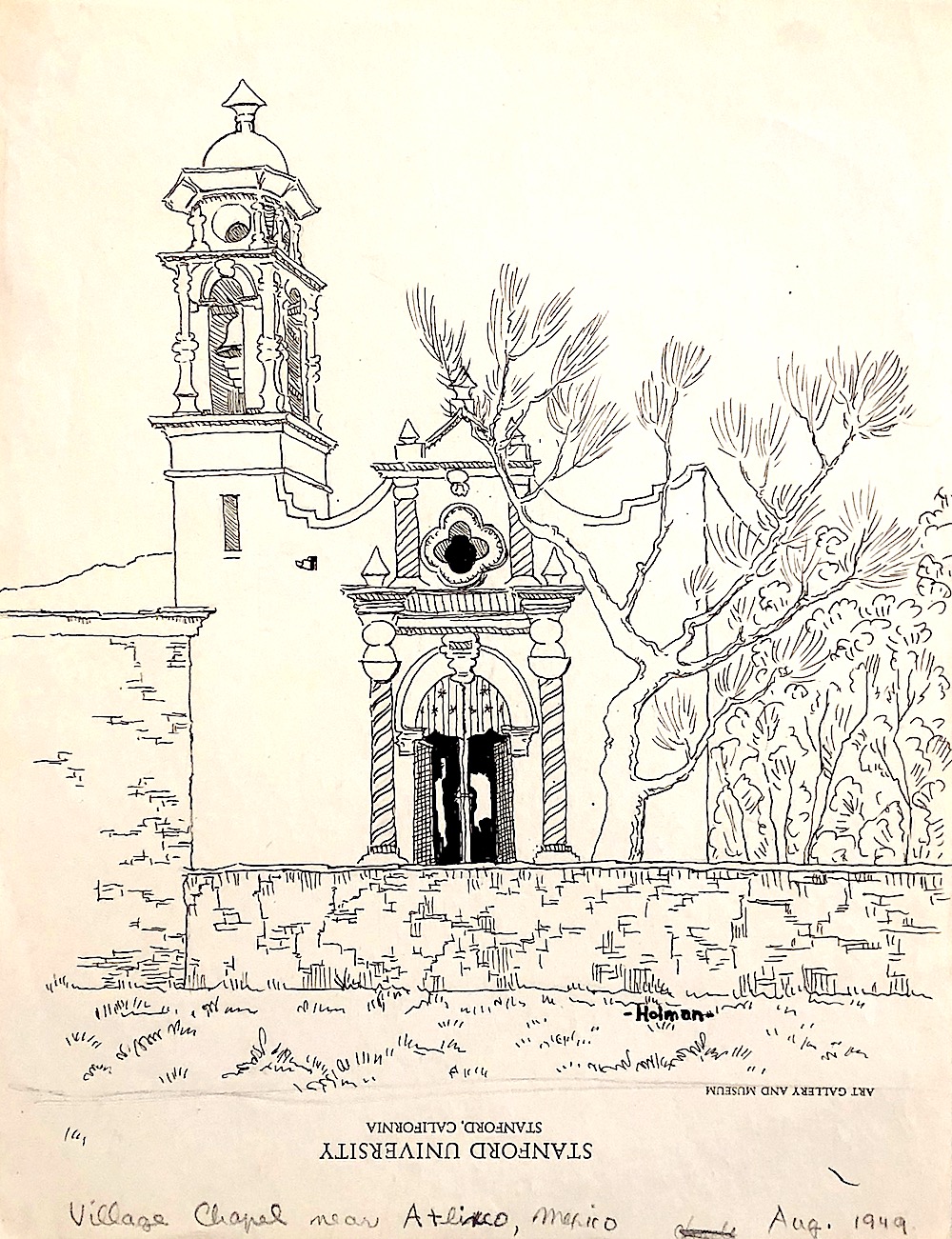

As a student at Stanford University during the 1940s, Bud Holman worked at the Stanford Museum. His job included piecing together thousands of pottery shards from the Cesnola collection from Cyprus, dating back to 2500 BC, which had been destroyed in San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake.

While at Stanford, Bud Holman joined the California Beta chapter of Phi Delta Theta. His father, Charles E. Holman, belonged to Phi Delta Theta at Washburn University. At this time, Bud Holman met Sarah Stein, the wife of Gertrude Stein’s brother Michael, who lived in Palo Alto. Stein was an influential art collector who befriended, supported, and popularized Henri Matisse. As Bud Holman sat down to tea in Stein’s living room, his gaze fell upon Woman in a Hat, Matisse’s seminal 1905 portrait of the woman with the green stripe down her nose. He was stunned by Stein’s formidable collection of early 20th century avant-garde French masterpieces. Her house was wall-to-wall with Matisses, Cezannes and Picassos. “Once when I opened a closet to hang up my coat,” Bud Holman recalls, “I found myself face-to-face with three Picasso portraits of the Stein family hanging on the inside of the door!”

Taking an interest in Bud Holman as a budding artist, Stein spent many afternoons with him in her garden, painting side by side. He still has a painting they made together of a bay tree, painted on the back of an old Masonite test board used for exams at Stanford. During the summers of his university years, Bud Holman landed a job as an artist with Sunset, being paid to travel to remote areas of Mexico to sketch scenes of old towns and cathedrals for the magazine.

After college, in 1953, Bud Holman accepted a position as the director of the Kansas State Historical Museum. The following year, Bud Holman headed for New York City. He found an artist’s studio with a huge skylight in the West Village and a job at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1957 and 1958, Bud Holman’s paintings were featured in group shows at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery with Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and Cy Twombly, who became a confidante. In 1959, Bud Holman showed his work at the prestigious Bertha Schaefer Gallery.

Bud Holman often stopped off at Twombly’s studio (where Twombly lived with Rauschenberg and Johns) to discuss art over beer and sandwiches. Twombly spent his last night in New York, before he moved to Rome, at a party thrown by Bud Holman.

In 1959, Bud Holman was hired by the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. Over the course of the next several years, he assembled a $12 million art collection for the 60-story Chase Manhattan Bank on Wall Street, under the direction of David Rockefeller.

In the 1960s, as he continued to paint, Bud Holman became friends with Warhol and Willem de Kooning, meeting up for drinks at the Cedar Bar in the East Village and Max’s Kansas City – “Artists’ hang-outs that were cheap places for serious drinking, where people got drunk out of their minds!” Bud Holman recalls.

Bud Holman traveled extensively during these years. “The three countries that have had the most impact on me in terms of color are Turkey, Egypt, and Morocco,” Bud Holman says. “I was heavily influenced by the swirl of action, the vibrant sense of color and color combinations, the patterns of tiles, and the exotic dress of the natives.”

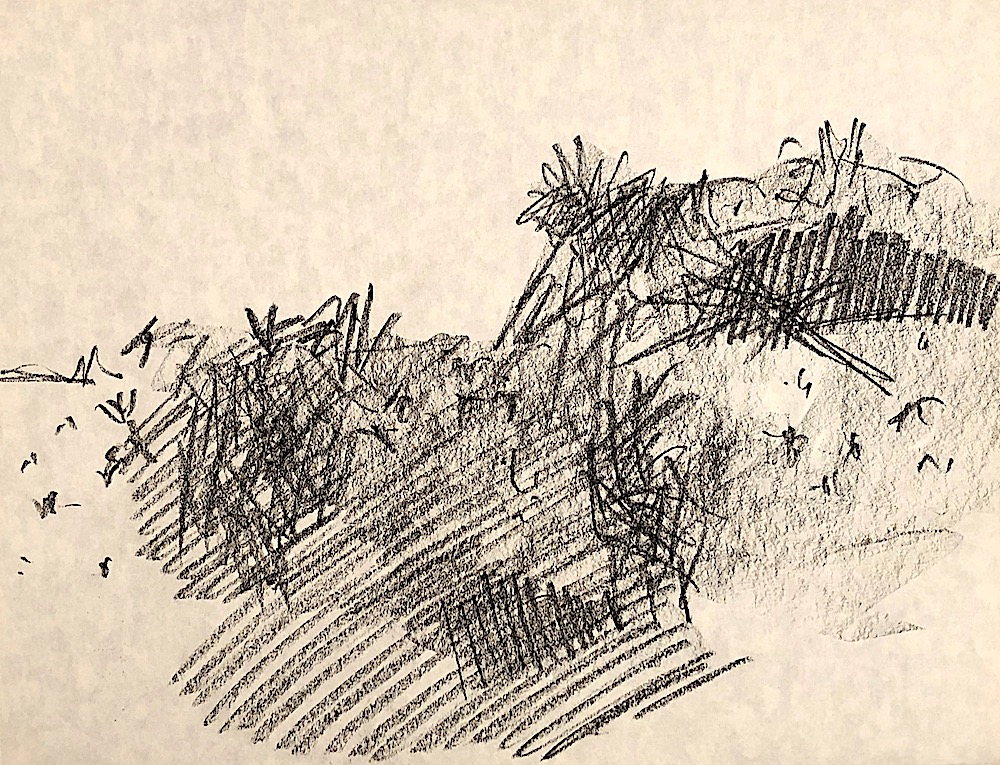

In the 1960s and 70s, Bud Holman spent summer weekends in Sagaponack, New York, painting the sea and dunes. In 1974, drawn to the freedom and open spaces of the Southwest, Bud Holman moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, purchasing a 225-year-old adobe hacienda on Canyon Road that he restored. He spent much time visiting all the pueblos along the Rio Grande and Acoma to observe the Native American dances and rituals.

In the late 1970s, he exhibited his paintings at the influential Jean Seth’s gallery on Canyon Road. Three of Bud Holman’s paintings were acquired by the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe and remain a part of their permanent collection.

There is a tactile quality to Bud Holman’s painting that sets the mood. He applied paint with aggression, creating multiple layers. Because the paint was applied thickly, Bud Holman had to allow it to dry for several days before applying the next layer, so he worked on several paintings at a time. He painted in what he refers to as a “pentimento” style, with underlying traces of past paintings barely visible beneath the surface. “Here and there,” Bud Holman said, “You can see a tidbit of a hidden layer hanging out on one side or the other of my paintings, like gardens overlaid many times for different uses.”

In Santa Fe, Bud Holman created a series of “painted constructions,” embalming bits of cinder rock, rope, wood, toothpicks, nails, spoons and gravel with paint.

In 1983, as Santa Fe became increasingly crowded, Bud Holman moved to Tucson. In 1992, four of his paintings were purchased by the Tucson Museum of Art.

At the heart of Bud Holman’s work was reverence for the desert in all its atmospheric moments. Bud Holman’s fervor for the Catalina, Santa Rita, and Tucson Mountains reverberates through his paintings. Those mountains are always present — some up close, others in the distance.

In 1996, seeking further solitude, Bud Holman left Tucson to build a house and studio in Nogales, Arizona, 60 miles south of Tucson, where he passed away in May 2023. Even entering his 90s he still painted most days from first light to dusk. “Painting is my way of life,” Bud Holman said. “The 16th century philosopher Michel de Montaigne declared, ‘I want death to find me planting my cabbages, neither worrying about it nor the unfinished gardening.’ ”

“That notion appeals to me,” Bud Holman mused. “I, too, would like to be found at the end of my life in my unfinished garden, in the midst of one last painting…”

Bud Holman returned to the west where he continued painting on a daily basis, but with no efforts to sell or show his work since 1974.

His estate collection is now being cared for in Phoenix by his heirs, who are seeking both museum exhibitions and gallery representation.