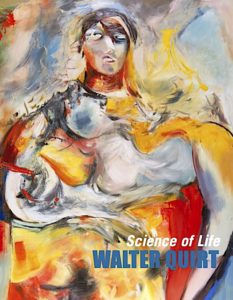

A Science of Life: The Return of Walter Quirt

— by Frederick Holmes

Introduction

In the telling of the story of 20th century Modern Art in America, we’ve all become familiar to varying degrees, of the same approximately twenty or so artists who comprise the overwhelming majority of the narrative—Pollock, Motherwell, DeKooning, Gorky, Rothko, Davis, et al. It’s only when we push aside this surface layer of the familiar, mining the strata beneath, that we discover the untold or forgotten stories. Often the stories are of those artists who perhaps enjoyed a momentary flare of critical or popular success and then as a result of personal life decisions, their inner demons, or simply being casualties of an often fickle art world, faded into obscurity. But seldom is there a case of an artist of both significant critical and popular accomplishment throughout most of his career, who in that same telling, posthumously becoming little more than a footnote.

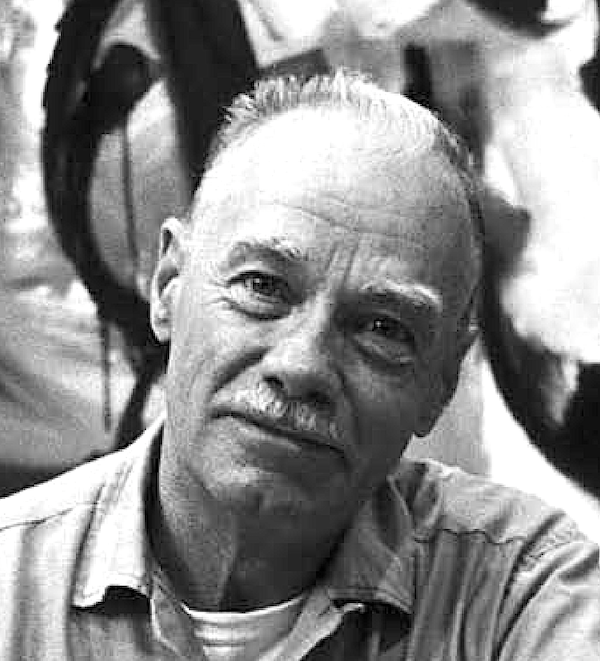

In the fall of 2014, I got a phone call from my friend and former gallery colleague, Travis Wilson. In 2012, the same year I’d relocated from San Francisco to Washington State, Travis had also left the gallery where we’d been working. Whereas I’d opened my own gallery in Seattle—Frederick Holmes And Company, Gallery of Modern & Contemporary Art—Travis became an independent curator in the Bay Area and had begun looking for intact art-historic estates of important, if often overlooked, artists. He established himself immediately with the discovery of two significant living painters for whom he coordinated individual exhibitions, that were met with enthusiastic reviews. But his call to me in 2014 was about an historic estate that would forever impact our lives.

“Fred” he began “I’m crossing Wyoming in a Penske truck and guess what I’ve got in the back?” “I don’t know, buddy, what?” I replied. “Walter Quirt — I’ve got twenty five paintings from the estate of Walter Quirt!” And like nearly everyone who’s been introduced to the name for the first time these last three years, I asked, “Who the hell is Walter Quirt?” To which he laughingly replied, “Google him and call me back!” Within two minutes I was back on the phone with him and had only two words: “I’m in!” From that point on we began a collaboration of curator and gallery, and one of the first important curatorial surveys of Walter Quirt’s work in nearly half a century was opened in Seattle, April 2015. In the catalogue published in tandem with the exhibition, Walter Quirt: Revolutions Unseen, Mr. Wilson recounts, “Several years ago I was flipping through the volume Abstract & Surrealist Art In America, written by Sidney Janis. In its pages I came across an image of a painting entitled, The Crucified (1943) by Walter Quirt and was taken aback. I remember emphatically saying to myself, “Who is that? Who is Walter Quirt?” At that time I could not have known the journey that awaited me as I have tried to answer that question.” That painting, The Crucified by Walter Quirt, printed as a black and white plate was on the opposite page facing a color plate of a painting entitled She-Wolf (1943) by an artist, who in Janis’ estimation represented, like Quirt, an emerging American avant-garde movement: Jackson Pollock. Abstract and Surrealist Art in America was considered one of the most important books of its day in it’s comparison of the intellectual movements of the European avant-garde and an emerging generation of American Moderns; that American painter being what Janis described as “a maker of a new world.”

New York, 1929–1944

Walter Quirt began his career initially as a student in 1921 at The Layton School of Art in Milwaukee, where by 1926 he was teaching drawing. It was during this time that he also became engaged with social activism, labor and class struggle. He enjoyed some regional success with his watercolors (he couldn’t afford oil paints) being exhibited in Milwaukee and even the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1929 he relocated to New York and quickly became acquainted with a small group of painters including Stuart Davis, Abe Rattner, Raphael Soyer, Louis Guglielmi and other members of a growing American modern movement. He joined the John Reed Club and became its secretary, organizing member exhibitions and publishing the organizations left-leaning pamphlets, often illustrated by Quirt.

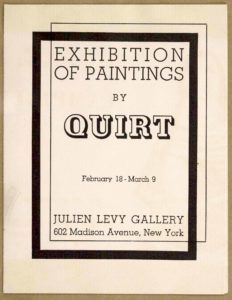

The 1930s were, of course, a time of great social/political/cultural upheaval and many artists work reflected the times. After World War I and the carnage witnessed by so many, there was a growing ideology among artists, intellectuals, and writers — both in Europe and America — influenced by Russian Contructivism, Suprematism, Futurism, and the increasing visibility of the Surrealists, that Modern Art could change society — the world — making it better through a radical change of consciousness. Growing up in a small, working-class mining town in Michigan, Walter Quirt was also keenly aware of the economic, civil, and racial inequities in American society when he arrived in New York, and increasingly his paintings, drawings, and writing began to express these sympathies. As a WPA painter, Quirt became bored and frustrated with the Social Realist style, prevalently favored by the arbiters of the WPA’S Federal Arts Project. By the mid-1930s he began integrating European Surrealism into Social Realism. It was then that he found critical success with a solo exhibition in 1936 at the Julien Levy Gallery simply titled, Exhibition of Paintings by Walter Quirt, comprised of fifteen small scale paintings described by several critical reviews as “revolutionary”. With the exception of Calder, Man Ray, (who were largely associated with the European avant-garde) and eccentric New York artist, Joseph Cornell, Julien Levy hadn’t shown much interest in American painters. His was one of the few galleries in New York exhibiting Surrealism—Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Rene Magritte, and others. In the press release announcing this exhibition, Levy wrote, “Whenever a new and vigorous contemporary painter appears on the horizon the Julien Levy Gallery has always wished to present his work to the judgment of its public, and in this case presents its first “radical painter.”

The 1930s were, of course, a time of great social/political/cultural upheaval and many artists work reflected the times. After World War I and the carnage witnessed by so many, there was a growing ideology among artists, intellectuals, and writers — both in Europe and America — influenced by Russian Contructivism, Suprematism, Futurism, and the increasing visibility of the Surrealists, that Modern Art could change society — the world — making it better through a radical change of consciousness. Growing up in a small, working-class mining town in Michigan, Walter Quirt was also keenly aware of the economic, civil, and racial inequities in American society when he arrived in New York, and increasingly his paintings, drawings, and writing began to express these sympathies. As a WPA painter, Quirt became bored and frustrated with the Social Realist style, prevalently favored by the arbiters of the WPA’S Federal Arts Project. By the mid-1930s he began integrating European Surrealism into Social Realism. It was then that he found critical success with a solo exhibition in 1936 at the Julien Levy Gallery simply titled, Exhibition of Paintings by Walter Quirt, comprised of fifteen small scale paintings described by several critical reviews as “revolutionary”. With the exception of Calder, Man Ray, (who were largely associated with the European avant-garde) and eccentric New York artist, Joseph Cornell, Julien Levy hadn’t shown much interest in American painters. His was one of the few galleries in New York exhibiting Surrealism—Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Rene Magritte, and others. In the press release announcing this exhibition, Levy wrote, “Whenever a new and vigorous contemporary painter appears on the horizon the Julien Levy Gallery has always wished to present his work to the judgment of its public, and in this case presents its first “radical painter.”

Quirt’s first show was received in this ideologically “radical” milieu and praised as “Revolutionary Surrealism” (Jacob Kainen/New Masses, Feb 26,1936) or dismissed as “propaganda.” Most however shared a favorable impression of the work best summarized here. “Quirt is the answer to the critic’s prayer for an art which shall be somewhere between the preciosity of the surrealists…and the passionate articulations of causists who feel that no painting has value unless it is an instrument of social revolution. . . Quirt works, like Dali, with a darker palette to be sure, but with composition, arrangement, meticulousness of brushwork and sensitivity of coloring which are comparable. But imagine the Dali technique applied to pictures. . . and then think of it flavored with the mural style of Orozco, if you possibly can. The results are as you must see for yourself, superb.” (Emily Genauer, World Telegram, February 27, 1936). This was the first of several shows with Levy that would galvanize Quirt’s reputation as a pioneer of a movement later deemed, “Social Surrealism.” The show quickly established Walter Quirt in New York’s critical and institutional arenas as a pioneering American surrealist. And when the still relatively new Museum of Modern Art, under the directorship of Alfred H. Barr, produced the groundbreaking exhibition, Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism later that same year, the museum co-produced a speakers symposium with the American Artists Congress, in order to better educate a public on this radical new movement. Among those featured speakers and representing the movement as artists, were Salvador Dali and Walter Quirt.

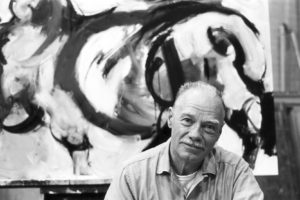

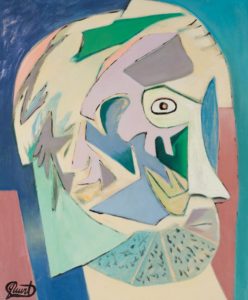

Quirt remained with Levy until 1940, by which time — always restless and excited about experimentation and new Modern theories — he moved on from Social Surrealism exploring an eclectic array of Abstract, Surrealist, and Cubist styles; yet each with his distinctive aesthetic imprimatur. This was an exciting time for many American painters who, while deeply self-conscious of the European avant-garde, were also trying to shake off its influence in their work in an effort to find their own uniquely American “language.” For Quirt, while diving deeper into varying styles of abstraction, the work nearly always retained one piece of connective, humanizing thread — the centrality of the figure. By 1944, through a succession of both gallery and museum shows, Quirt was well known and highly respected by fellow artists and gallery dealers in New York. “There was a relatively small group of well-known American painters in New York during WW II, and Quirt was one of the most influential.” (Prof. Peter Selz / 2015) It was in 1944 when Robert Coates, critic for The New Yorker (and who coined the term, “Abstract Expressionism”) in his enthusiastic review of Quirt’s solo show with the Durlacher Brothers Gallery—the same exhibition where the aforementioned The Crucified was being presented—exuberantly proclaimed, “Walter Quirt is one of the most impassioned artists alive today!”

Post New York, 1944–1966

Whereas most of Quirt’s contemporaries remained in New York after WWII, and successfully climbed the ladder of critical and commercial success with the support of now legendary gallerists, Peggy Guggenheim, Betty Parsons, and Sidney Janis, as well as art critics like Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, Walter Quirt left New York in the summer of 1944. The WPA/FAP government stipend providing a subsistence stipend for many professional artists — creating paintings, murals, and sculpture for federal buildings, train stations, post offices, etc. — was terminated in 1943. The following year, his wife, Eleanor, announced the happy news to her husband that she was pregnant. Walter felt the responsibility of supporting a family took precedence over his still ascendant career. So, like many artists of that period, he began teaching — initially at the Layton School of Art, Milwaukee; then the University of Michigan, East Lansing; and ultimately in 1947, at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

It was in Minneapolis, far from post-war New York and the powerful wave of Abstract Expressionism with its attendant media storm of hyperbolic praise and criticism as well as growing commercial profit, that Quirt observed the triumphs and tragedies that consumed many of his contemporaries. It’s also fair to say that Quirt, an irascible, fiercely independent artist, had by the time of his exodus irritated a few dealers by refusing to follow any advice or comply with the whims of the market. Developing a “signature style” that would make his work more identifiable and marketable, was anathema to his self-image as a theoretician of art as much as painter. A favorite anecdote recounts an afternoon when Peggy Guggenheim arrived in his studio unannounced and after a brief introduction imperiously dismissed a group of works in the studio while expressing her favor of another grouping. She offered him a solo show with the caveat he was to produce an equal number of paintings in the style of the latter grouping. Quirt, still very much the anti-capitalist and not one to be told what to paint or for whom, viewed Ms. Guggenheim and her offer as a Faustian bargain. Forcefully refusing her offer, he also told her never to enter his studio again without an invitation. His close friend, Stuart Davis, with whom he maintained an exchange of correspondence for years, teasingly quipped that Quirt had left New York “just ahead of the hanging party.”

And yet through numerous gallery and museum shows, Quirt continued to maintain a powerful, if personally less visible, presence in the city, remaining a still critical figure in the enfolding canon of American Modern. As the years passed the artist was now free of financial constraints thanks to his teacher’s salary. Less ideologically strident, Quirt’s work became less about social progress and increasingly aesthetically progressive. It was also in the early 1950s, while feeling isolated from the community of artists and friends in which he’d once held such a prominent, respected role, when he began drinking more heavily, perhaps due to this same sense of isolation, and it showed in some of the work. His palette became predominated by grays and muted tones of mauves, blues, ambers, and black. The overall mood of the figures was pensive, and often seemed alienated from the world around them: Doubt, (1952); Dilemma, 1953; Pensive Girl,1952. Yet he was simultaneously able to transcend his more somber mood and create work that was remarkably joyous and even whimsical: Woman With Bare Feet, 1953; Fun, 1950; Road With No Turn, 1952. Still a fearless experimenter, he retained a reputation in New York as working on the leading edge of American Modern. Between 1938 and 1959, Walter Quirt was included in no less than seven Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting juried shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Along with Quirt, this last Whitney Annual in 1959 included work by important contemporary artists, such as Kurt Seligman, Hans Hoffman, and Jimmy Ernst. Between 1942 and 1965, his paintings were also included in six various group exhibitions produced by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Following his inclusion in the 1958–1959 Whitney Annual, Quirt was given a retrospective in 1960 by The American Federation of Arts with a grant from the Ford Foundation, which toured over two and a half years, exhibiting through seventeen cities and venues. Critic Robert Coates, still an enthusiastic supporter of Quirt’s work wrote the essay for the retrospective’s catalogue, asserting that Quirt’s “paintings have grown larger in size too…and his color has become freer. Certainly, there are suggestions of Willem de Kooning’s tribal figures in Quirt’s The Eyes Have It (1957) though from the date …what would seem to be indicated is something in the way of parallel development rather than an influence.”

Between the late 1950s through the mid-1960s, Quirt remaining true to form, delved into a variety of subjects and styles. According to Robert Coates, “Quirt expanded his use of the counter-curve in compositions and brushstrokes…from 1957, explaining in his essays that he equated this motion with positive non-aggressive energy: ‘The psychological purpose of the counter-curve is to transform physical objects endowed with aggression into love…there is only one energy in art. It is Aggressive Energy. When this energy is released competitively the diagonal line plays a subordinate role to the S-shaped curve, symbol for feeling.’ ”(University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: Mary Towley Swanson, Walter Quirt: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, 1980). In her essay for Walter Quirt: A Retrospective, guest curator Mary Towley Swanson wrote, “Sudden stylistic changes in his compositions were unimportant to Quirt in the forties and early fifties, since he wrote that his main goal was to study and reveal man’s relationship to nature and society…The counter-curve, the more civilized linear element according to Quirt, was often found as a basis for paintings from the late fifties through the mid-sixties. Critics reacted favorably to Quirt’s facility with a brush in his exhibition at the Duveen-Graham Gallery in New York, January 22-February 9, 1957.” This period is predominated by abstract “monumental figures” in varying configurations; Horses; and abstract landscapes largely inspired by Lake Harriet, a recreational lake near the family home that Quirt used to visit and enjoy watching people picnic, playing games, swimming or sailing.

In 1961, a new series of experimental works also begin to emerge, Use of White — bold figurative paintings with aggressive, staccato-like black brushwork juxtaposed in fields of varying tones and whites. What we know of Quirt from this period, the mid-1950s through the sixties, is that his singlemindedness about the value and importance of line was such that he would even occasionally abandon color altogether, and with one brush and two cans of paint — black and white — force himself to bear down and focus on its prominence in the painting, such as in Horse, 1959. Like many other Modern painters, Walter Quirt made several trips to Mexico, drawn by its primitive topography, its history, people, and culture; the last of these being December 1966 through February 1967. He spent three months in the Yucatan, Mexico, working on what could have become recognized as one of his most remarkable achievements had he lived a little longer: The Quirt Hypothesis. His was a fascinating theory — that one could infer from a culture’s or individual’s preference in their art, crafts, architecture, dress, etc, an implied attitudinal perspective of their environment and reality; essentially their “social psychology.” (see “The Yucatan Project” and “The Quirt Hypothesis” in catalogue.) Although Quirt had long before abandoned explicit “social revolution” in his varying styles of painting, he never really abandoned his theory of art as capable of raising or stirring consciousness; indeed, he saw it as art’s duty and the artist’s mandate. In a letter written to his sister, Leila, in 1962 from San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, he stated, “A basic theoretical problem in art is to so unite the social tempo with Nature’s Time that one arrives at the Timeless, a quality in Time that is independent of both.” Five years later, while in the Yucatan for the final time — now under the auspices of The Yucatan Project — he wrote Leila again emphatically asserting that “…art contains the principles of a science of life, that it always has…I assure you, the next science will be art…that is the use of principles in energy in art applied to social problems.” Approximately fifteen months after making this prediction, Walter Quirt passed away from cancer, on March 19, 1968.

Epilogue

Today, decades later, Pollock, Davis, Bearden, de Kooning and other contemporaries of Walter Quirt have become ensconced in the narrative surrounding the development of Modern Art in America. Quirt, on the other hand, following his death in 1968, in spite of what had been a critically successful career, slowly faded into the haze of history. Some of this was due to post-Modern America’s cultural inclination of toppling the past in order to elevate the new. But much of the responsibility for Quirt’s ignominy in today’s world was due in no small part to his widow, Eleanor. Grief-stricken after her husband’s death in 1968, she made the fateful decision to keep her husband’s work close to her and her family, seldom allowing it to be publicly presented or sold. With the exception of three exhibitions at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis between 1968 and 1980 — the last being Walter Quirt: A Retrospective — the paintings and drawings remained largely out of sight over nearly half a century, and his legacy slowly slipped off the radar of the public. Still, he wasn’t entirely forgotten. In MoMA’s 1999 publication on Jackson Pollock — considered by many to be the definitive tome on the artist — co-editor and art historian, Pepe Carmel, wrote, “Quirt may be virtually forgotten today, but in 1944, he and Pollock seemed like promising young artists of comparable importance.”

Today, decades later, Pollock, Davis, Bearden, de Kooning and other contemporaries of Walter Quirt have become ensconced in the narrative surrounding the development of Modern Art in America. Quirt, on the other hand, following his death in 1968, in spite of what had been a critically successful career, slowly faded into the haze of history. Some of this was due to post-Modern America’s cultural inclination of toppling the past in order to elevate the new. But much of the responsibility for Quirt’s ignominy in today’s world was due in no small part to his widow, Eleanor. Grief-stricken after her husband’s death in 1968, she made the fateful decision to keep her husband’s work close to her and her family, seldom allowing it to be publicly presented or sold. With the exception of three exhibitions at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis between 1968 and 1980 — the last being Walter Quirt: A Retrospective — the paintings and drawings remained largely out of sight over nearly half a century, and his legacy slowly slipped off the radar of the public. Still, he wasn’t entirely forgotten. In MoMA’s 1999 publication on Jackson Pollock — considered by many to be the definitive tome on the artist — co-editor and art historian, Pepe Carmel, wrote, “Quirt may be virtually forgotten today, but in 1944, he and Pollock seemed like promising young artists of comparable importance.”

In 2005, nearly forty years after his death, Walter Quirt’s 1935 painting, The Future Is Ours (which had been included in Quirt’s first solo show with the Julien Levy Gallery in 1936), appeared in a survey of American surrealism, Surrealism USA, along with two fellow contributors to Social Surrealism, James Guy and David Smith. New York Times critic, Roberta Smith, singled out Quirt’s painting stating its composition “…recasts a group of American farmers, sailors, and soldiers, as menacing xenophobes and gives its famous title a selfish ring that resonates today.” That same year, the Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa, opened an exhibition of surrealism, The Irrational and The Marvelous, exhibiting a painting by Walter Quirt, Animal Studying Its Tracks, (1951).

2019 saw the publication of the Museum of Modern Art’s book, Among Others: Blackness at MoMA, chronicling the history of African-American artists, marginalized by racism and in the Museum’s permanent collection. Recognition in the publication was also given to several non-Black artists who through their work and writings, had vehemently opposed racism. Walter Quirt’s, Burial (1936), also in the museum’s permanent collection, was included and poignantly illustrated the artist’s opposition to racism and bigotry. The painting’s subject as relevant today as when he first painted it over 85 years ago.

Figurative Expressionism

-

DETAILS

DETAILSNatures Children, 1942

40 x 48 inches (101.6 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWoman of Sorrows, 1958

66 x 41 inches (167.64 x 104.14 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDrawing Canvas, c.1958

40 x 50 inches (101.6 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStanding Invitation, 1958

50 x 30 inches (127 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTree of Hope, 1959

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGrand Pose, 1958–59

70 x 40 inches (177.8 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSHorse 711, 1959

40 x 60 inches (101.6 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled Horse, 1959

48 x 66 inches (121.92 x 167.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSHorse and Man, 1959

50 x 58 inches (127 x 147.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhite Seated Figure, c.1961

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGreen Lavender Horse, 1959

56 x 50 inches (142.24 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLone Cowboy, 1959

50 x 58 inches (127 x 147.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSRace Against Time, 1959

60 x 49 inches (152.4 x 124.46 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure 232, 1960

40 x 50 inches (101.6 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure 500, 1960–61

58 x 42 inches (147.32 x 106.68 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSong of the Guitar, 1959

58 x 40 inches (147.32 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract Figure, 1960

35 x 23 inches (88.9 x 58.42 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlue and Yellow Figure, 1964

30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled Lake Harriet, 1964

24 x 30 inches (60.96 x 76.2 cm)