What Degas Might Have Done

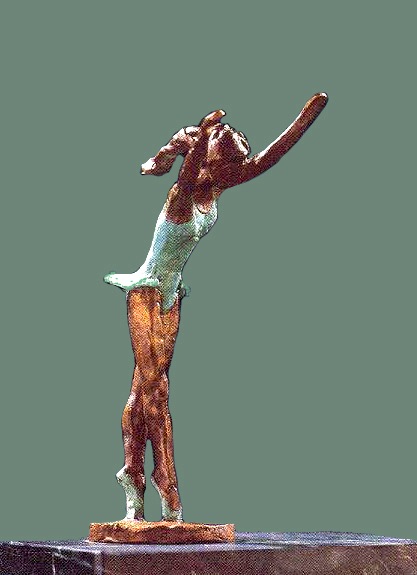

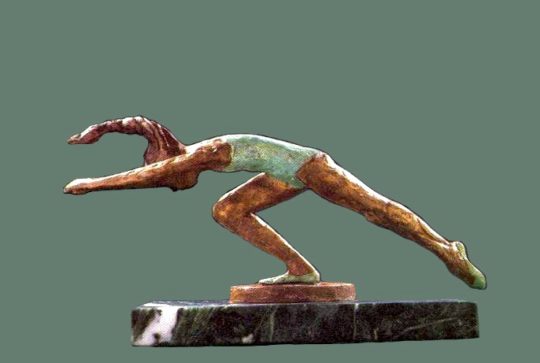

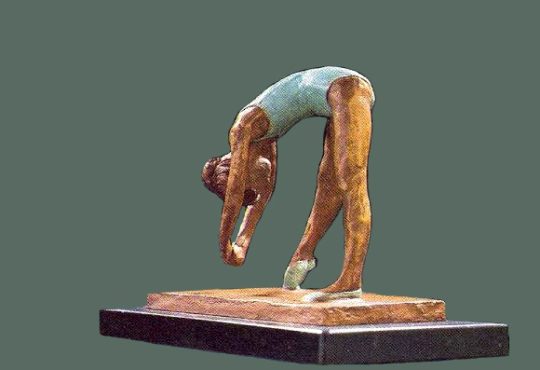

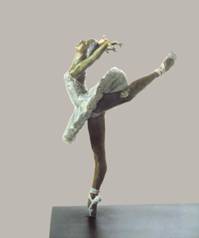

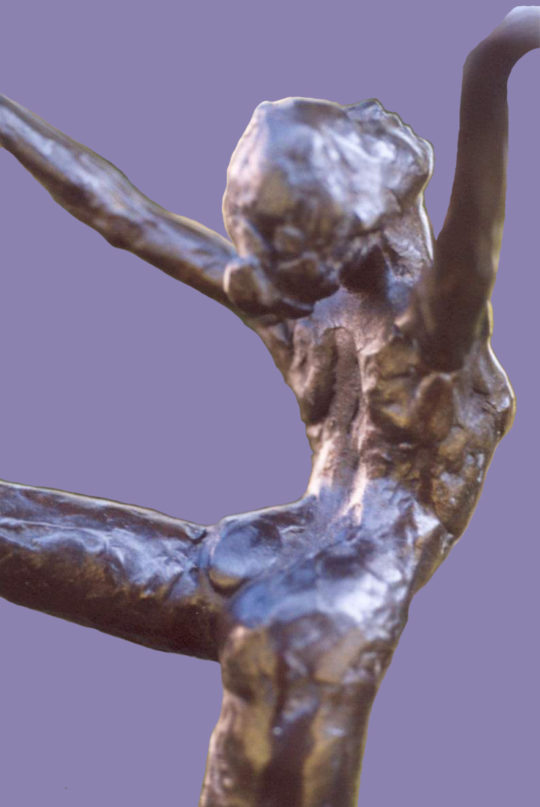

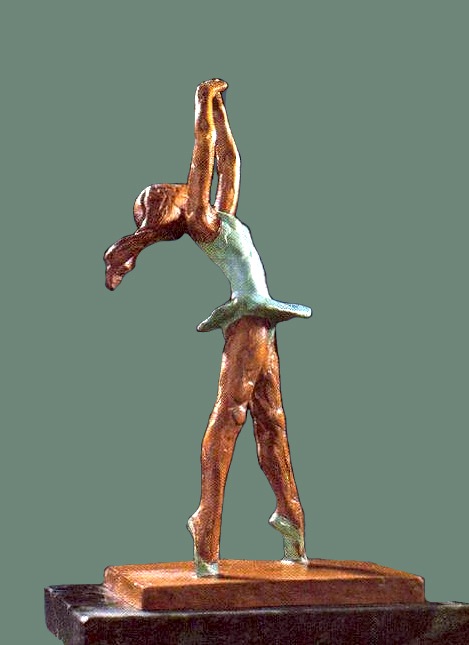

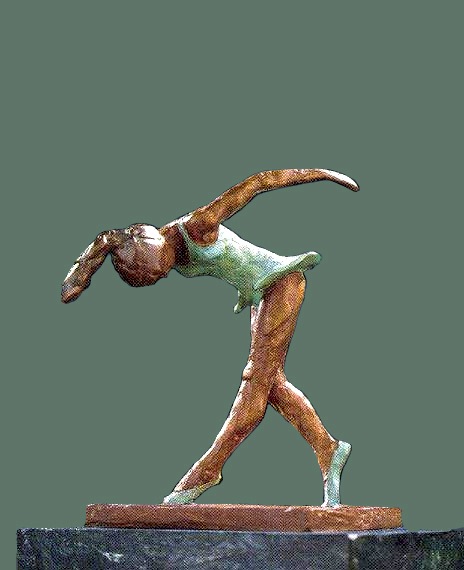

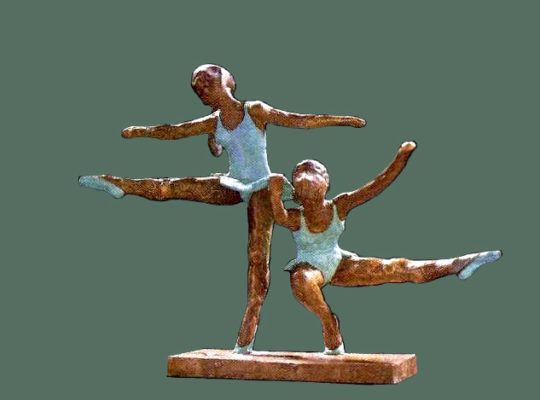

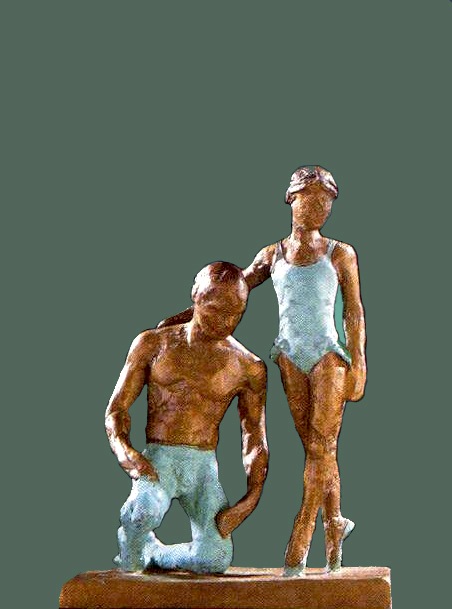

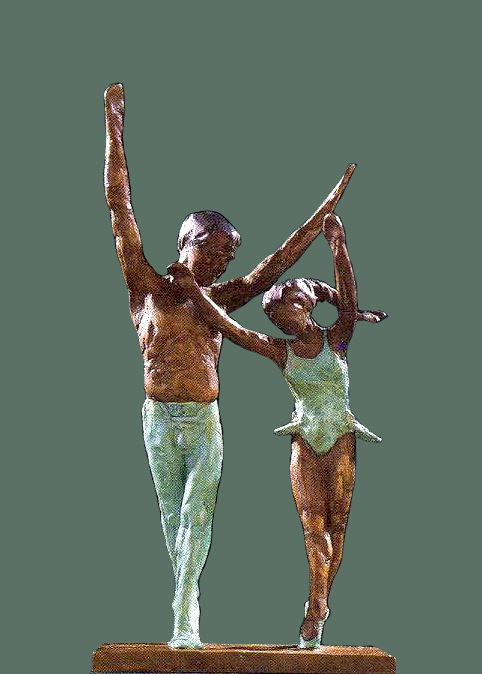

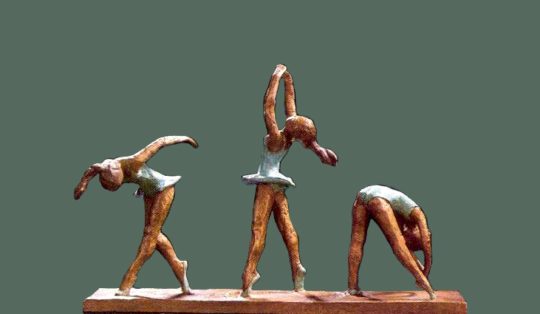

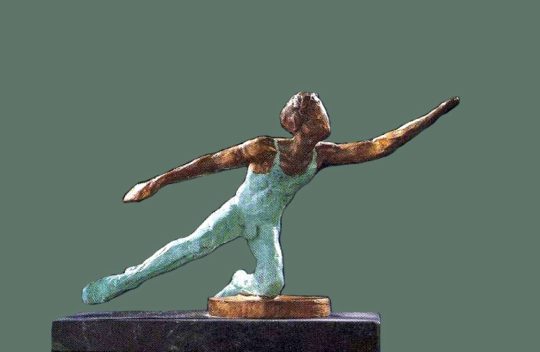

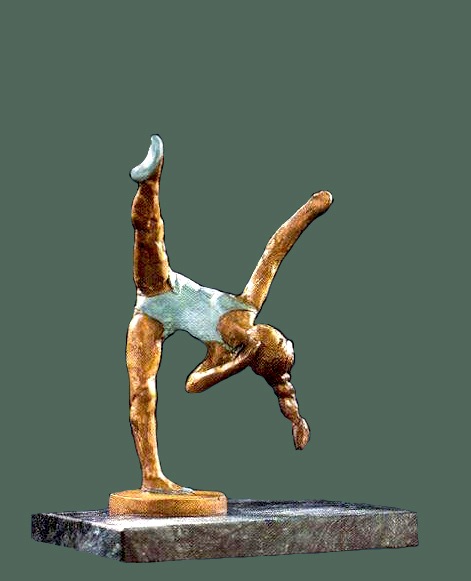

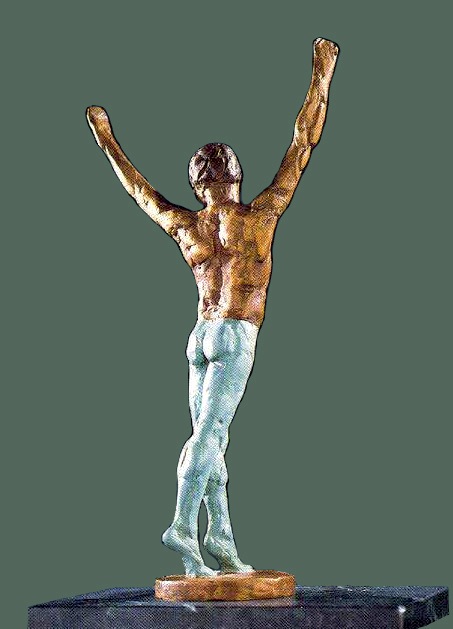

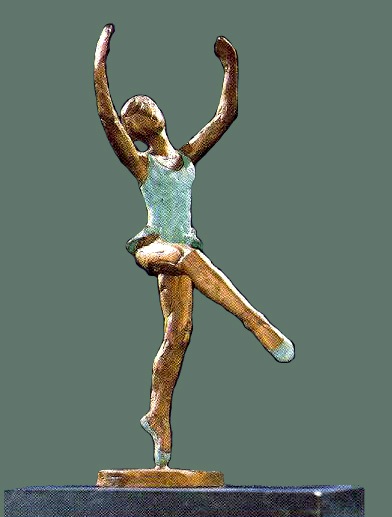

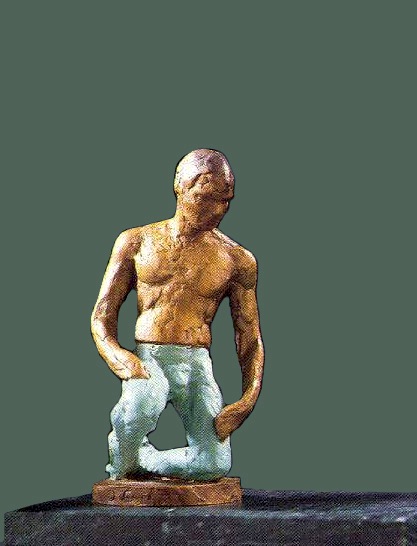

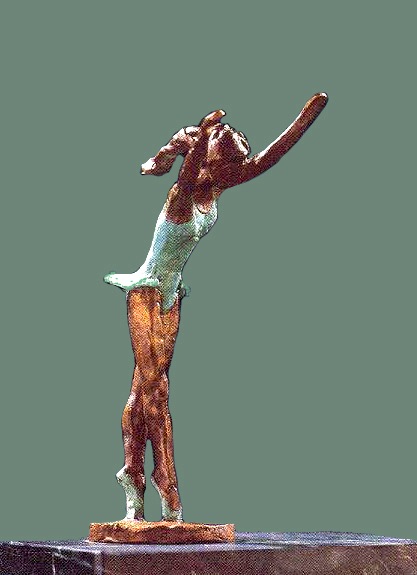

From the moment I was hooked on bronze in 1962 it has been my quest to capture the essence of dance in that medium. Fifty years and nearly three-hundred original sculptures later, the challenge remains as strong as ever: I strive to imbue each figure with an independent spirit, implied movements, and an imagined soul while being faithful to the choreographic tenets and spirit of ballet.

— Sterett-Gittings Kelsey

No artist in history is more synonymous with dance than the French Impressionist Edgar Degas [1834-1917]. In his brilliant compositions he captured the ballerina’s intimate moments — and movements — from her practice halls to her performances at the Paris Opéra. Many of his paintings and pastels of dance have rightfully achieved iconic stature. But it is important to point out that these paintings are finished products with a purpose entirely different from that of his sculptures. When Degas died in 1917 his family discovered more than 150 small figures in wax and clay in his studio. He had never exhibited them — with the exception of his famous The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer. Nor did he conceive of enlarging his wax studies to monumental size as did Rodin, Carpeaux, and other sculptors of his time. Nonetheless, just a year after his death his estate authorized 72 of them to be cast posthumously as editions by the Paris foundry, Hébrard. Had they conferred with the master when he was living he would have told them that his little wax studies of dancers were experimental — part of a grand a process that, like his sketches, were meant to sharpen his visual acuity for capturing fleeting moments of graceful movement. He would have reminded them that even his photography served the same role as an aide memoire. And he would have told them that despite his blindness, from which he had been suffering gradually since the mid 1870s, he had found special joy in immersing himself in such a tactile process.

Dance sculpture was for Degas a very private exercise. Indeed, he intended for only a single one of them to be exhibited. Therefore, art historians must question the validity of grouping his paintings with what was originally a clandestine body of maquettes to serve together as the standard for the subject of dance. This begs the question: If Degas does not lay rightful claim as the greatest sculptor of dance, who does? There have been many sculptors throughout history who have been inspired by dance but who among them has dedicated their lives to the subject and achieved excellence?

This essay proposes that if Degas is accepted as the undisputed master painter of dance — specifically ballet — then the subject’s undisputed master sculptor is Sterett-Gittings Kelsey.

At this point it must be mentioned that every art historian remains guarded about being accused of resorting to hyperbole. The temptation to interject even a single instance of it risks damaging a professional reputation. And in an art world whose very nature is imbued with subjective judgment art historians constantly find themselves either averse to taking a stand or busily fortifying a defense that validates their positions. But the world’s art historians and museum curators have already weighed in on history’s greatest artists, further grouping them according to various thematic categories that combine period, style, medium, nationality, and subject matter — and many consensuses have been found. Indeed, college level art history textbooks have reconfirmed this principle of consensus as have those many books and exhibition catalogues focusing on specialized categories. However, there is one special medium-subject combination that has never received thorough academic treatment: dance and sculpture.

Art history abounds with magnificent examples of dance sculpture. Among the earliest are those terra-cotta figures created by the ancient Minoans thirty-six hundred years ago. Twenty-two hundred years ago sculptors of Classical Greece captured sacred dances and Dionysian rites in clay and marble. And caves in Orissa, India, have revealed sculptures of Odissi dance from the same period, which are a graceful and spiritual fusion of dance and sculpture. But one would be hard-pressed to find an artist who has dedicated most of his or her life to the subject of dance — and even harder pressed to find one who has focused upon ballet as has Kelsey.

That search would begin in 1669 with Louis XIV’s founding of the Paris Opéra. Later, during the Romanticism of the eighteenth century ballet evolved as an art form in its own right. But it was not until the mid nineteenth century when ballerinas, dancing in tutus on their tip-toes, displaced male dancers in the spotlight. And when Charles Garnier’s new Paris Opéra finally opened in 1875 Degas intensified his quest to capture the movement and gestalt that is unique to ballerinas. By the time he exhibited his The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer with the Impressionists, in 1881, the Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburg had displaced Paris as the center of the dance world. It took a revolution brewing in Russia to relocate the Ballets Russes to Paris, and throughout the 1920s the company thrived under the direction of Diaghliev. This modern era of dance imposed new strict training regimens and exacting body proportions, which were required to execute demanding performances. The dancers’ bodies and costumes that were captured by Degas in the last quarter of the nineteenth century had vanished before the end of his life.

Amidst the next generation of American sculptors who came to Paris there were four women who attempted to capture the Russian dancers in bronze. Harriet Whitney Frishmuth [1880-1980] was admired for her expressive nude poses of Desha Delteil while Malvina Hoffman [1885-1966] won early recognition for her portraits of Anna Pavolva. Both sculptors had studied with Rodin. Bessie Potter Vonnoh [1872-1955] created a few rhythmical bronzes, the best of which is of a dancer in a full flowing gown. Janet Scudder [1869-1940] also created a few dancing figures. While all four of these very talented women sculptors brilliantly expressed the movement of dance in bronze during the 1910s-1920s their involvement with ballet was at best either brief or tangential. Frishmuth stands out as the most accomplished in expressing elegant movement while Hoffman focused more on the sculpted portrait. Both Vonnoh and Scudder found success with their bronzes by concentrating on children, figures for fountains and gardens, and portrait commissions.

Emerging during the 1880s and successful through the early twentieth century was the great triumvirate of American male sculptors: Augustus Saint-Gaudens [1848-1907], Daniel Chester French [1850-1931], and Frederick MacMonnies [1863-1937]. While each of these men could effectively express movement in their bronzes none of them considered dance — particularly ballet — as a subject that stimulated their visual exploration. In Paris only one male sculptor, Demetre Chiparus [1886-1947], stands out for his sculptures of the ballet. In a distinctive Art Deco style he combined ivory with cast bronze to produce many sculptures inspired by the dancers of the Ballets Russes.

By 1929 both Chiparus and the Ballets Russes had ended their runs. The next major development in dance came in 1934 when George Ballanchine founded the School of American Ballet and his dance company, the New York City Ballet, founded in 1948. He not only carried on Diaghliev’s demanding requirements of his dancers but also developed a new choreography in concert with major composers. Indeed, very few of the dancers immortalized by Degas would qualify for the New York City Ballet. Thus, anyone attempting to capture modern dance in sculpture would not only have to be highly sensitive to the gestalt of the profession but a faithful student of the choreographic correctness of ballet’s many new movements. But no such sculptor emerged.

***

The year after Chiparus died a seven-year-old American girl fell in love with ballet when she attended a birthday party at “Red Oaks,” the magnificent Victorian home of Katharine Phillips Rutgers in Greenwich, Connecticut. Here she discovered an exquisite collection of little porcelain ballet dancers. Mrs. Rutgers, who had been a world-class ballerina, explained the stories behind each of the porcelain dancers. She then brought the transfixed girl to her ballet studio on the third floor, which was filled with costumes from the many ballets in which she had danced.

It seems as if Sterett-Gittings Kelsey had already been destined to become America’s “sculptor of dance.” She and her twin sister, Easy, were raised on their grandparents’ 350-acre farm, “ Bacon Hall, ” in the bucolic countryside of Glencoe, Maryland, north of Baltimore. It was a child’s dream world. The stream passing through the farm was lined with gray clay in which the little hands of Kelsey delighted in fashioning pots and plates. And she was born in 1941, the year of Balanchine’s premier of his ballet, Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2.

When the family moved to Greenwich in 1947 the sisters took their first pony-riding classes and subsequently competed in the National Horse Show over the years until they went to college. Thus began a life-long fascination with controlled graceful movements in both dancing and riding. If her childhood play with clay from the banks of a stream sparked her first pleasure in creating three-dimensional forms it was an art instructor at the Garrison Forest School in Maryland who was the catalyst for her addiction to sculpture. Working in Plasticine, the non-drying clay, she created her first figure on an armature.

Returning to Greenwich in 1956, she spent her final two years at the Rosemary Hall School where she studied under the accomplished octogenarian painter, Julius Delbos [1879-1970]. She and her sister also took private lessons in ballet from dancer-choreographer Felicity Foote, who had studied modern dance in Europe. From 1960 to 1964 Kelsey attended the Rhode Island School of Design where the discipline learned from an intense anatomy class under Michael B. Mazur [1935-2009] left a lasting impression. She studied sculpture under John Bozarth and Thomas Morin. In 1962 Morin’s class built the school’s first furnace for casting, which was completed after several weeks. The experience of casting her first bronze had her hooked! The capture of movement remained her focus and in the summers of 1963 and 1964 she choreographed with Felicity Foote, who had further established herself by founding the Greenwich Ballet Workshop in 1960. Kelsey created a light show that began with the shadows of her sculptures of dancers. The shadows then moved in synchrony with the live dancers and each performance ended with the live dancers in the same position as the shadows of her sculptures.

After graduation from R.I.S.D. Kelsey married Bowie Duncan, who taught English at the Wilbraham Academy in Massachusetts. A son was born in 1966 and a daughter in 1968. However, a calamity in the form of a very rare and usually fatal Salmonella D meningitis threatened the life of her infant daughter for more than a year. Miraculously, the baby survived. Having endured this nearly tragic experience Kelsey returned to sculpture more determined and impassioned than ever. Reflecting upon the vigilance and discipline imposed by her baby’s bumpy yet miraculous recovery, Kelsey noted, “I doubt that I could have become a sculptor had it not been for Salmonella D. All of my education would not have been used in any meaningful way. Without having learned a new work ethic I call “freedom of discipline” these works would never have been produced. Of this I am certain. There are many parts and pieces that must come together to make a sculptor but for me the most important ingredient was discipline.”

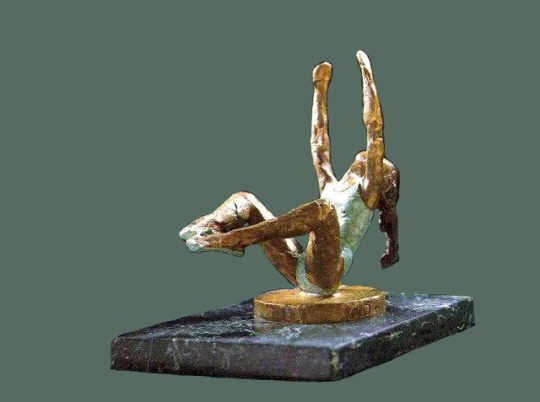

That discipline included the study of dance, choreography, and music through what became a large archive of videotapes of ballet and movies about dance. Certainly, the spontaneity of playing with wax or clay remained just as important a part of her “sketching” process as it was for Degas. “Much of the creativity comes from these little sketches but a finished work is like moving from a single melody line to a full symphony,” she says. And moving to that symphony meant choosing to replay the video cassette recorder over and over — a discipline that provided a newly-focused way of capturing motion as well as learning about film production, choreography, and set design. Soon, her past training with dance teachers, choreographers, musicians, sculpture professors, and even pony-riding instructors became integrated as an innate sense for capturing motion. “My sculpture would come from this acquired library of sounds and images, which scrambled themselves into my head, and then found their way to my hands,” she says. “I was determined to try to capture movement in my work and somehow make it sing.” Numerous films of movies and dance continued to serve as catalysts for new works. For example, in 1981 at age forty she produced two of her favorite sculptures after studying the masterful choreography of Choo San Goh in his ballet, Configurations, which was commissioned by Mikhail Baryshnikov for the American Ballet Theater and set to the music of Samuel Barber’s piano concerto. “It took my breath away!” she exclaimed.

Equally important has been Kelsey’s technical understanding of every step in the process of creating a bronze, from clay to molds, casting, finishing, and patination. For example, while creating the original figure in clay she is acutely aware of the need to compensate for the inevitable shrinkage found in the final bronze casting. Her early works were cast at the Renaissance Fine Art Foundry in Noroton, Connecticut. Since 1971 the Polich Tallix Fine Art Foundry in Rock Tavern, New York — known for having produced bronzes for Willem De Kooning, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, and other masters — has cast most of her bronzes.

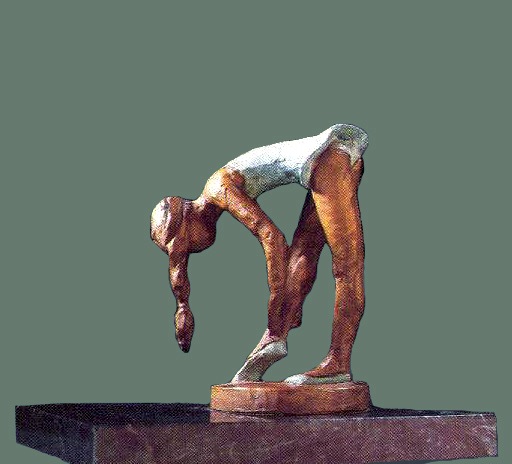

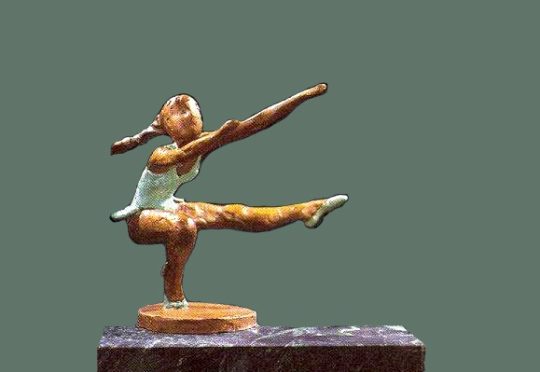

In 1966 Royal Copenhagen of Denmark desired to produce a new series of sculptures expressing different types of figural movement. In their quest to find that singular master sculptor for their project they held international competitions. Seven years later, in 1973, they finally found Kelsey. She embarked on a three-year commission, first producing fourteen porcelain figurines of children and ballerinas — and purposefully depicted the young girls dancing incorrectly in their naïveté. Next, she produced eight dance figures cast in bronze in limited editions of five-hundred. They sold out within forty-eight hours of their release. Her third contract resulted in twelve more limited editions in bronze, this time focusing on sports such as fencing, tennis, skating, gymnastics, and soccer. In order to fully understand each sport’s movement she was instructed by a champion in each sport such as Olympic cross-country skier Bill Koch and Olympic skater Dorothy Hamill.

Throughout her career Kelsey has consistently maintained the same enthusiasm for capturing lyrical movement in both humans and animals. However, ever since she was a starry-eyed seven-year-old encountering ballet in Mrs. Rutger’s attic studio it is the movement unique to modern ballet that has exerted from her the most assiduous commitment. She does not focus on the sequential positions — First, Second, Third, Fourth, and Fifth — with which all balletomanes are intimately familiar. For Kelsey, those positions are basically stationary and lack perceived movement. Rather, she captures most of her figures in those moments just before or just after these positions. Like Cartier-Bresson photographing a “decisive moment,” this decision is what brings life to her dancers.

If Degas had more fully developed many more of his small clay or wax figures to the same final stage as he did his famous The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer he would doubtlessly have achieved the same strong gestalt for dance that makes his paintings and pastels such masterpieces. But as this was never his intention the collection of his dance sculpture — all experimental maquettes save one — cannot reasonably be invoked as the standard for dance sculpture. That honor must be conferred upon Sterett-Gittings Kelsey.

***

POST SCRIPT

On December 21, 1988, one of Kelsey’s neighbors was the victim of the Lockerbie Bombing, the infamous Pan American flight No.103, which was blown up by Islamic terrorists. The tragedy, which claimed 270 lives, was the catalyst for Kelsey’s creation of a small angel in bronze donated to the memorial garden in Lockerbie, Scotland. “I named the little angel Joy because I wanted to celebrate the lives of those lost, not their deaths. Joy was shipped quietly to Lockerbie with no fan fare. I was just hoping, as one artist, to bring a bit of comfort to the town.” Twenty years later, upon hearing Bob Dole announce that American troops were being short-changed, an angry Kelsey set out to enlarge Joy to monumental size and call her The Freedom Angel.

In 2010 the Freedom Angel Foundation was formed with the mission of building a new national monument, dedicated to America’s heroes and recognizing the debt owed to our military. The foundation plans the ongoing use of Kelsey’s Freedom Angel logo as the unifying emblem for America’s returning veterans and it will be placed on various products in order to raise the dollars needed for their care.

— Peter Hastings Falk

More information on Kelsey’s sculptures may be found at:

http://kelseysculpture.artspan.com/

More information on the Freedom Angel Foundation may be found at:

http://www.freedomangelfoundation.org

Dance: What Degas Might Have Done

-

Alexandra of Middle Patent Farm (back detail), 1980

42 x 56 inches (106.68 x 142.24 cm) -

Alexandra of Middle Patent Farm (frontal view), 1980

42 x 56 inches (106.68 x 142.24 cm) -

Alexandra of Middle Patent Farm (side view), 1980

42 x 56 inches (106.68 x 142.24 cm) -

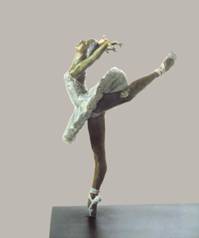

Attitude Croisée (back), 1999

42 x 87 inches (106.68 x 220.98 cm) -

Attitude Croisée (foot), 1999

42 x 87 inches (106.68 x 220.98 cm) -

Attitude Croisée (left), 1999

42 x 87 inches (106.68 x 220.98 cm) -

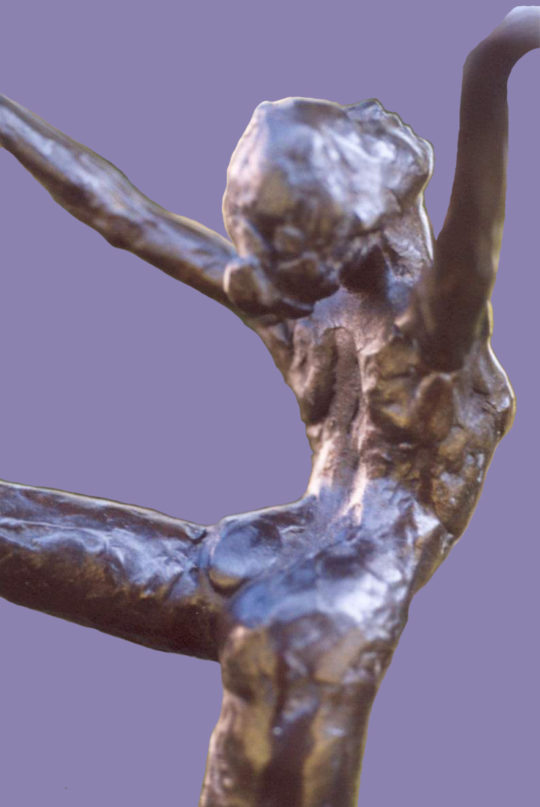

Ballanchine’s Dancer, Elise Boyce Kelsey (back), 2006

28 x 78 inches (71.12 x 198.12 cm) -

Ballanchine’s Dancer, Elise Boyce Kelsey (left front), 2006

28 x 78 inches (71.12 x 198.12 cm) -

Ballanchine’s Dancer, Elise Boyce Kelsey (waist), 2006

28 x 78 inches (71.12 x 198.12 cm) -

Clara and Her Beloved Nutcracker (back), 1999

38 x 55 inches (96.52 x 139.7 cm) -

Clara and Her Beloved Nutcracker (shoes detail), 1999

38 x 55 inches (96.52 x 139.7 cm) -

Clara and Her Beloved Nutcracker (right), 1999

38 x 55 inches (96.52 x 139.7 cm) -

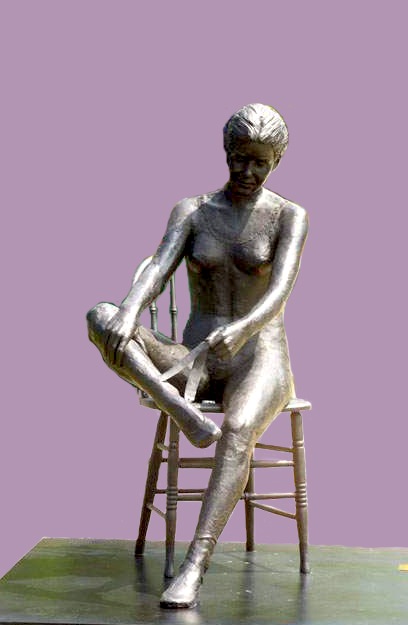

Felcity Foote and Sabina Cartier (Degas Dancers at Rest), 1989

15 x 6 inches (38.1 x 15.24 cm) -

Felcity Foote and Sabina Cartier (Degas Dancers at Rest) (detail), 1989

15 x 6 inches (38.1 x 15.24 cm) -

Felcity Foote and Sabina Cartier (Degas Dancers at Rest) (from above), 1989

15 x 6 inches (38.1 x 15.24 cm) -

Garry-Gunther (detail), 1995

6 x 12 inches (15.24 x 30.48 cm) -

Garry-Gunther (front), 1995

6 x 12 inches (15.24 x 30.48 cm) -

Garry-Gunther (right), 1995

6 x 12 inches (15.24 x 30.48 cm) -

Kasha Bukowsky of Sound View Loop (frontal), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Kasha Bukowsky of Sound View Loop (left side), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Kasha Bukowsky of Sound View Loop (right side), 1998

32 x 75 inches (81.28 x 190.5 cm) -

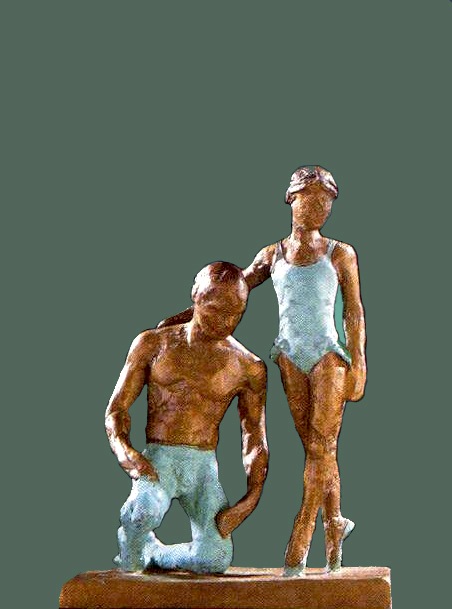

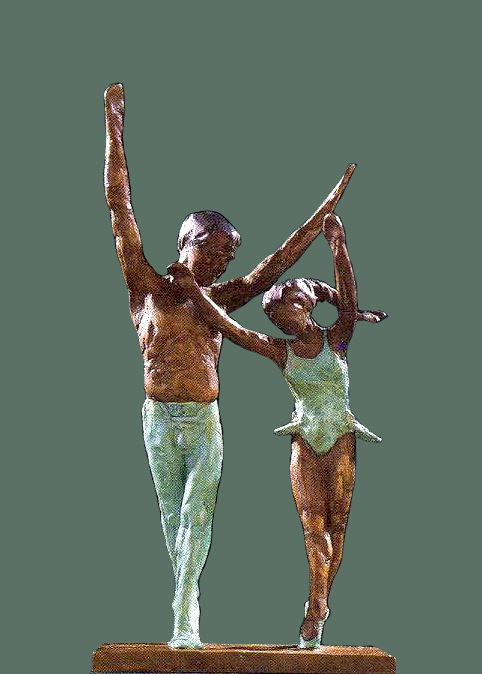

Love Sketch III, 1976

3.5 x 5 inches (8.89 x 12.7 cm) -

Love Sketch IV, 1976

5.5 x 4.5 inches (13.97 x 11.43 cm) -

Love Sketch V, 1976

4 x 6 inches (10.16 x 15.24 cm) -

Love Sketch VI, 1976

4 x 3.5 inches (10.16 x 8.89 cm) -

Love Sketch VII, 1976

5 x 6 inches (12.7 x 15.24 cm) -

Makarova’s Marina Maguire of Rosemary Hall (back), 1996

7 x 12 inches (17.78 x 30.48 cm) -

Makarova’s Marina Maguire of Rosemary Hall (left), 1996

7 x 12 inches (17.78 x 30.48 cm) -

Makarova’s Marina Maguire of Rosemary Hall (right), 1996

7 x 12 inches (17.78 x 30.48 cm) -

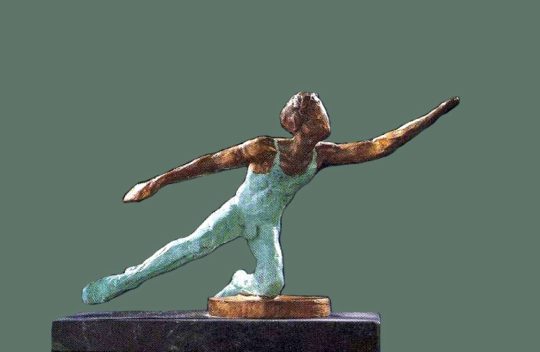

My Maiorano, 2006

6 x 9.5 inches (15.24 x 24.13 cm) -

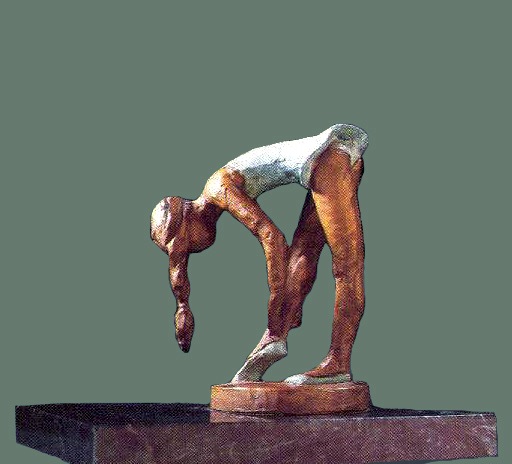

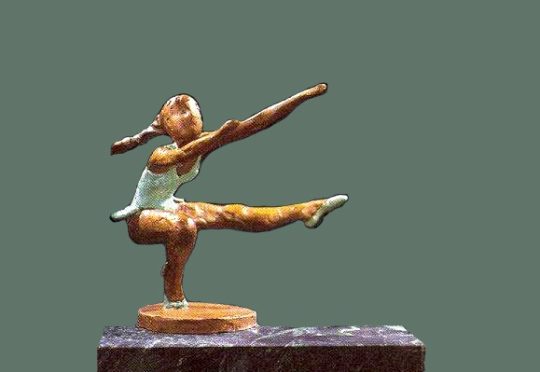

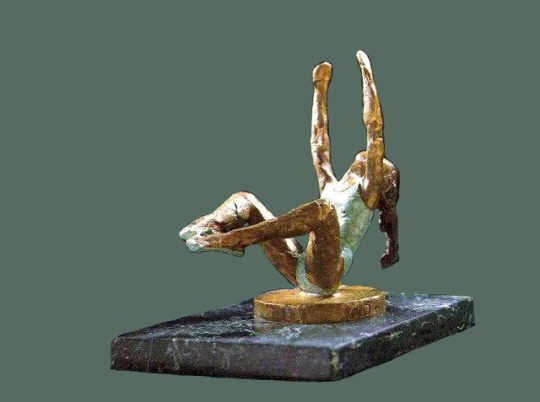

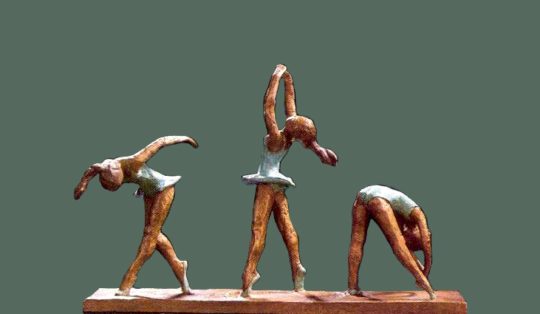

Opus 1 (from the Corps de Balet Collection), 1984

3 x 4.5 inches (7.62 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 10 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

5 x 4.5 inches (12.7 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 11 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 4.5 inches (11.43 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 12 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

5 x 6 inches (12.7 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 13 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 14 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 15 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 6 inches (11.43 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 16 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

8 x 6 inches (20.32 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 17 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 18 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

5 x 7.5 inches (12.7 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 19 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

13 x 5.5 inches (33.02 x 13.97 cm) -

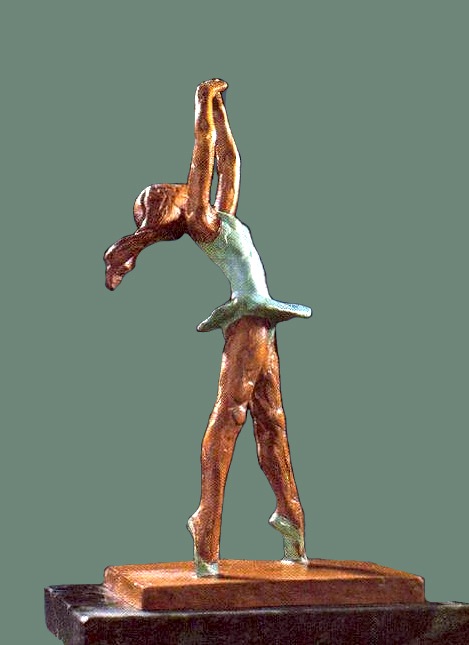

Opus 2 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

6 x 4 inches (15.24 x 10.16 cm) -

Opus 20 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5 inches (11.43 x 12.7 cm) -

Opus 21 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 22 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3 x 7.5 inches (7.62 x 19.05 cm) -

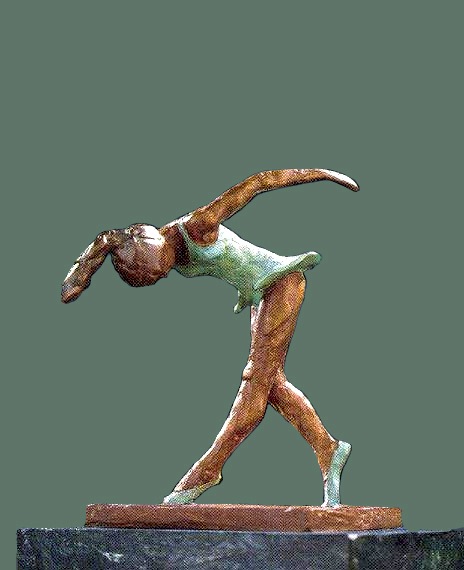

Opus 3 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

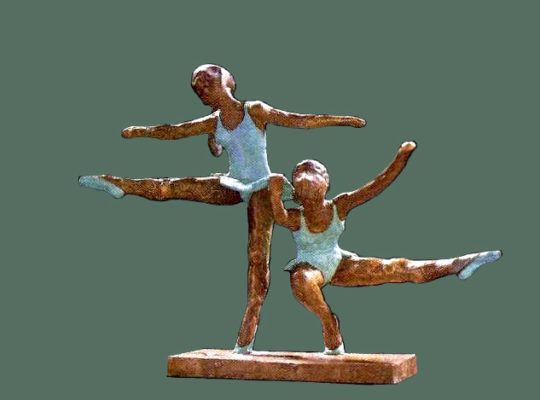

Opus 4 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 5 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3 x 4.5 inches (7.62 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 6 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7 inches (8.89 x 17.78 cm) -

Opus 7 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3 x 6 inches (7.62 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 8 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

8 x 3.5 inches (20.32 x 8.89 cm) -

Opus 9 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 4.5 inches (8.89 x 11.43 cm) -

Swan Lake’s Princess Odette (frontal detail), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Swan Lake’s Princess Odette (left side), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Swan Lake’s Princess Odette (right side), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

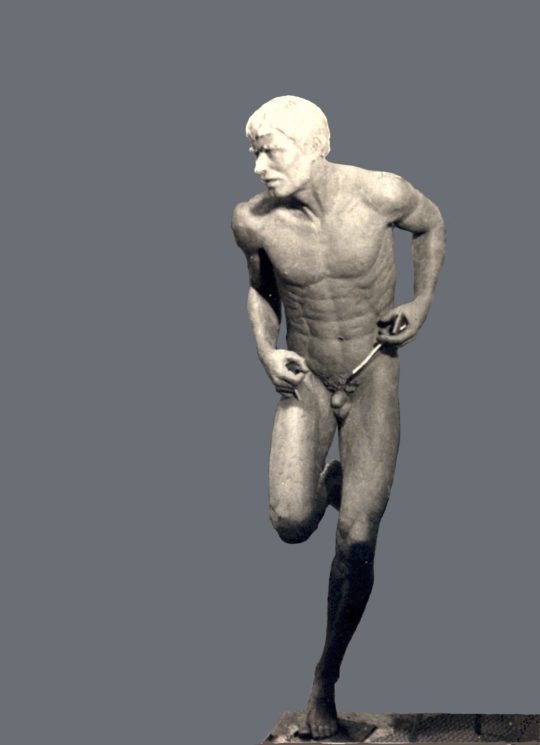

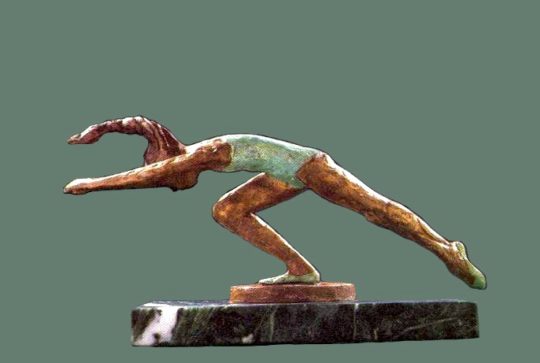

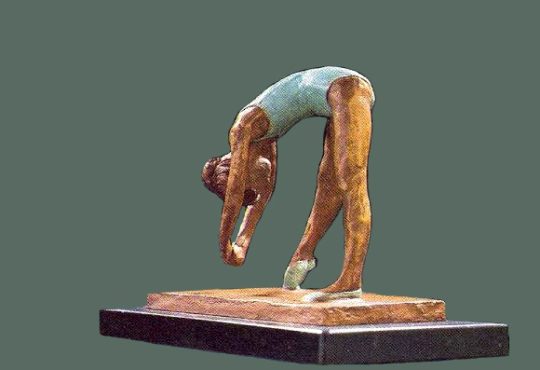

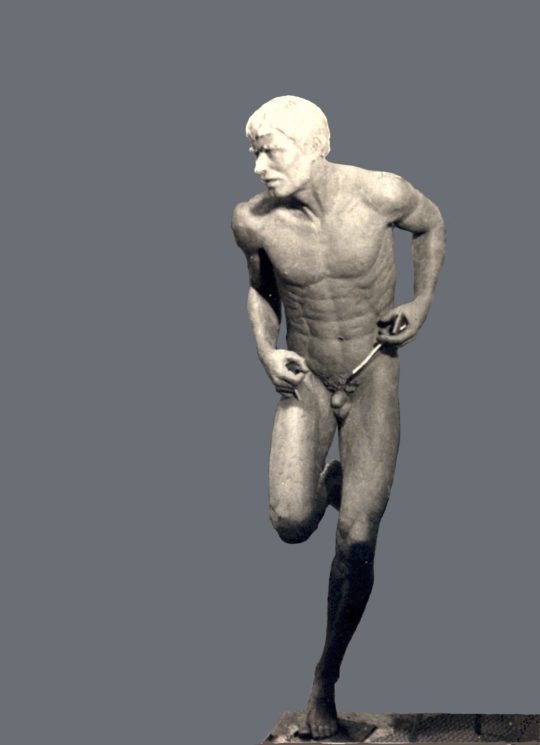

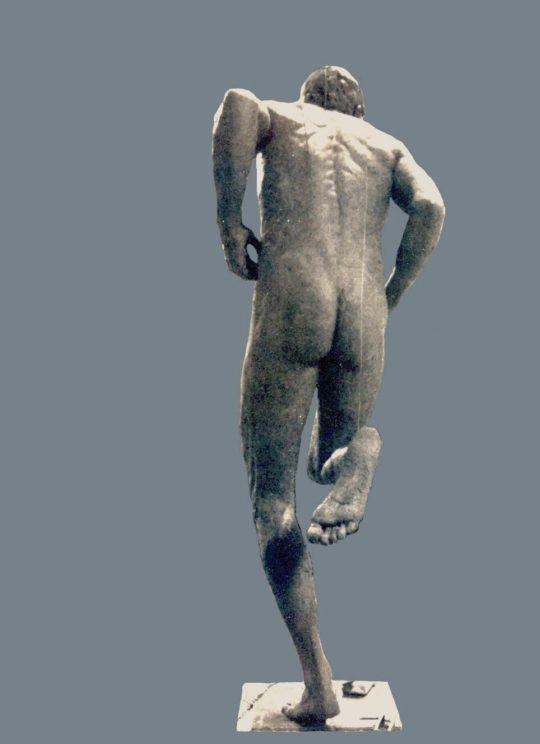

The Orienteer (National monument to the sport of Orienteering, Sweden), 1974

30 x 108 inches (76.2 x 274.32 cm) -

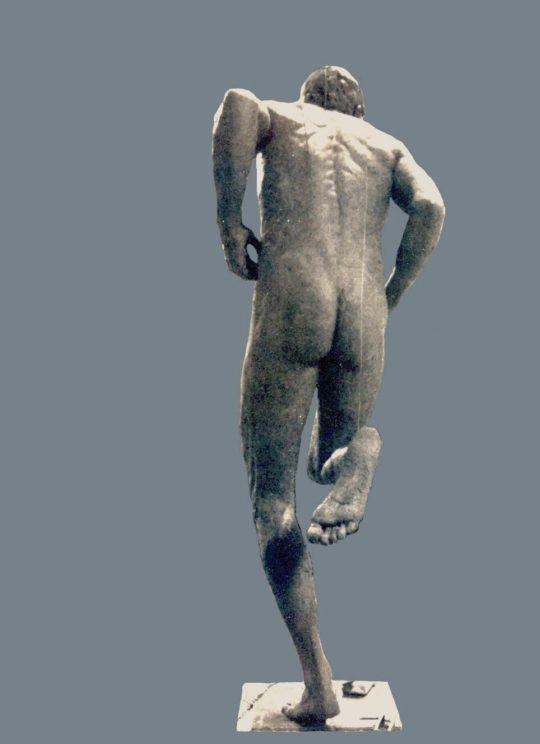

The Orienteer (National monument to the sport of Orienteering, Sweden) (back), 1974

30 x 108 inches (76.2 x 274.32 cm) -

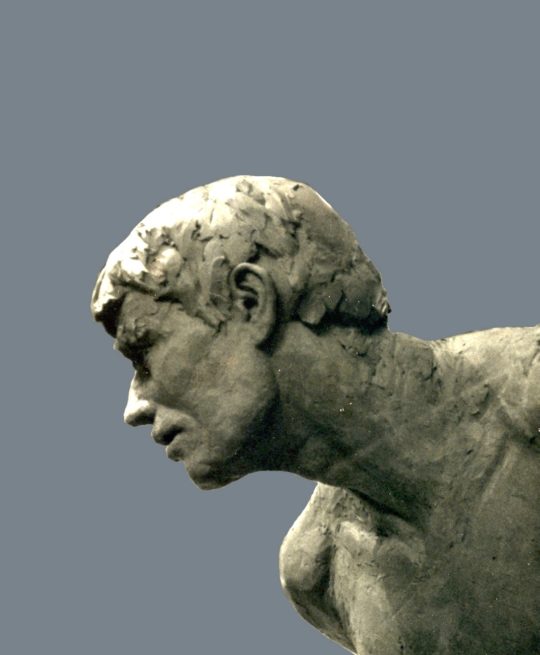

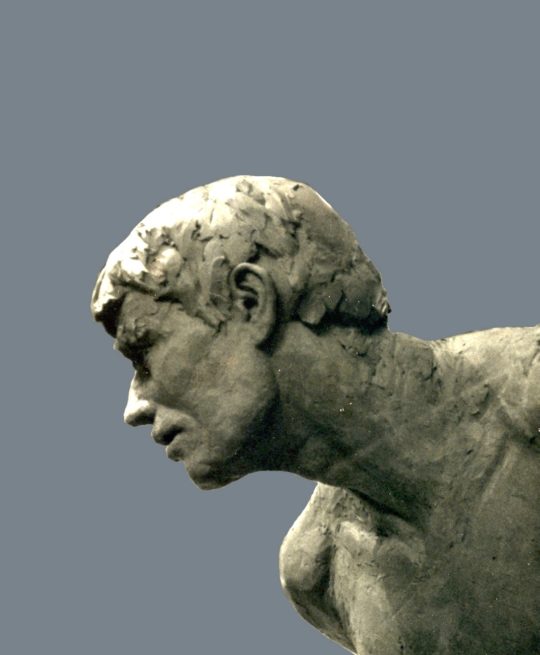

The Orienteer (National monument to the sport of Orienteering, Sweden) (detail), 1974

30 x 108 inches (76.2 x 274.32 cm) -

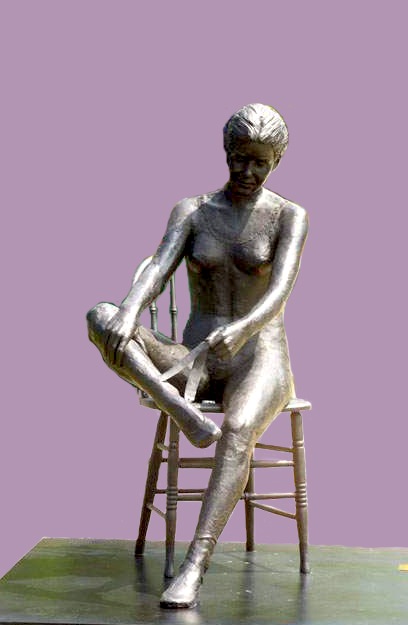

Vanessa Helena, 1988

75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm) -

Vanessa Helena (back detail), 1988

75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm) -

Vanessa Helena (skirt detail), 1988

75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm) -

Wendy Ross, 1993

6 x 10 inches (15.24 x 25.4 cm)

-

Alexandra of Middle Patent Farm (back detail), 1980

42 x 56 inches (106.68 x 142.24 cm) -

Alexandra of Middle Patent Farm (frontal view), 1980

42 x 56 inches (106.68 x 142.24 cm) -

Alexandra of Middle Patent Farm (side view), 1980

42 x 56 inches (106.68 x 142.24 cm) -

Attitude Croisée (back), 1999

42 x 87 inches (106.68 x 220.98 cm) -

Attitude Croisée (foot), 1999

42 x 87 inches (106.68 x 220.98 cm) -

Attitude Croisée (left), 1999

42 x 87 inches (106.68 x 220.98 cm) -

Ballanchine’s Dancer, Elise Boyce Kelsey (back), 2006

28 x 78 inches (71.12 x 198.12 cm) -

Ballanchine’s Dancer, Elise Boyce Kelsey (left front), 2006

28 x 78 inches (71.12 x 198.12 cm) -

Ballanchine’s Dancer, Elise Boyce Kelsey (waist), 2006

28 x 78 inches (71.12 x 198.12 cm) -

Clara and Her Beloved Nutcracker (back), 1999

38 x 55 inches (96.52 x 139.7 cm) -

Clara and Her Beloved Nutcracker (shoes detail), 1999

38 x 55 inches (96.52 x 139.7 cm) -

Clara and Her Beloved Nutcracker (right), 1999

38 x 55 inches (96.52 x 139.7 cm) -

Felcity Foote and Sabina Cartier (Degas Dancers at Rest), 1989

15 x 6 inches (38.1 x 15.24 cm) -

Felcity Foote and Sabina Cartier (Degas Dancers at Rest) (detail), 1989

15 x 6 inches (38.1 x 15.24 cm) -

Felcity Foote and Sabina Cartier (Degas Dancers at Rest) (from above), 1989

15 x 6 inches (38.1 x 15.24 cm) -

Garry-Gunther (detail), 1995

6 x 12 inches (15.24 x 30.48 cm) -

Garry-Gunther (front), 1995

6 x 12 inches (15.24 x 30.48 cm) -

Garry-Gunther (right), 1995

6 x 12 inches (15.24 x 30.48 cm) -

Kasha Bukowsky of Sound View Loop (frontal), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Kasha Bukowsky of Sound View Loop (left side), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Kasha Bukowsky of Sound View Loop (right side), 1998

32 x 75 inches (81.28 x 190.5 cm) -

Love Sketch III, 1976

3.5 x 5 inches (8.89 x 12.7 cm) -

Love Sketch IV, 1976

5.5 x 4.5 inches (13.97 x 11.43 cm) -

Love Sketch V, 1976

4 x 6 inches (10.16 x 15.24 cm) -

Love Sketch VI, 1976

4 x 3.5 inches (10.16 x 8.89 cm) -

Love Sketch VII, 1976

5 x 6 inches (12.7 x 15.24 cm) -

Makarova’s Marina Maguire of Rosemary Hall (back), 1996

7 x 12 inches (17.78 x 30.48 cm) -

Makarova’s Marina Maguire of Rosemary Hall (left), 1996

7 x 12 inches (17.78 x 30.48 cm) -

Makarova’s Marina Maguire of Rosemary Hall (right), 1996

7 x 12 inches (17.78 x 30.48 cm) -

My Maiorano, 2006

6 x 9.5 inches (15.24 x 24.13 cm) -

Opus 1 (from the Corps de Balet Collection), 1984

3 x 4.5 inches (7.62 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 10 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

5 x 4.5 inches (12.7 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 11 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 4.5 inches (11.43 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 12 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

5 x 6 inches (12.7 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 13 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 14 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 15 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 6 inches (11.43 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 16 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

8 x 6 inches (20.32 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 17 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 18 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

5 x 7.5 inches (12.7 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 19 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

13 x 5.5 inches (33.02 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 2 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

6 x 4 inches (15.24 x 10.16 cm) -

Opus 20 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5 inches (11.43 x 12.7 cm) -

Opus 21 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

Opus 22 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3 x 7.5 inches (7.62 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 3 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 4 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

Opus 5 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3 x 4.5 inches (7.62 x 11.43 cm) -

Opus 6 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 7 inches (8.89 x 17.78 cm) -

Opus 7 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3 x 6 inches (7.62 x 15.24 cm) -

Opus 8 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

8 x 3.5 inches (20.32 x 8.89 cm) -

Opus 9 (from the Corps de Ballet Collection), 1984

3.5 x 4.5 inches (8.89 x 11.43 cm) -

Swan Lake’s Princess Odette (frontal detail), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Swan Lake’s Princess Odette (left side), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

Swan Lake’s Princess Odette (right side), 1999

10 x 15 inches (25.4 x 38.1 cm) -

The Orienteer (National monument to the sport of Orienteering, Sweden), 1974

30 x 108 inches (76.2 x 274.32 cm) -

The Orienteer (National monument to the sport of Orienteering, Sweden) (back), 1974

30 x 108 inches (76.2 x 274.32 cm) -

The Orienteer (National monument to the sport of Orienteering, Sweden) (detail), 1974

30 x 108 inches (76.2 x 274.32 cm) -

Vanessa Helena, 1988

75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm) -

Vanessa Helena (back detail), 1988

75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm) -

Vanessa Helena (skirt detail), 1988

75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm) -

Wendy Ross, 1993

6 x 10 inches (15.24 x 25.4 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

No Events Found.