Art historians are finally beginning to realize that the power of abstraction in its early years was a zeitgeist not limited to the major European centers of the avant-garde — Paris, Munich, and Moscow — but one that quickly rippled to major cities throughout the world. Within a few decades that original shock of a new vision had inspired thousands of artists from different cultures — particularly those the Middle East — whose translations were not slavish imitations of works by seminal figures like Picasso, Braque, Malevich, and Kandinsky but creative variants colored by their respective cultures.

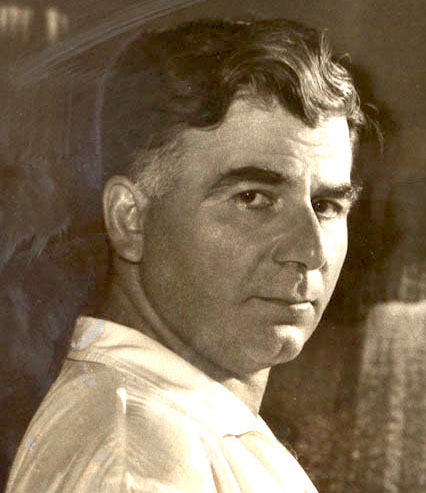

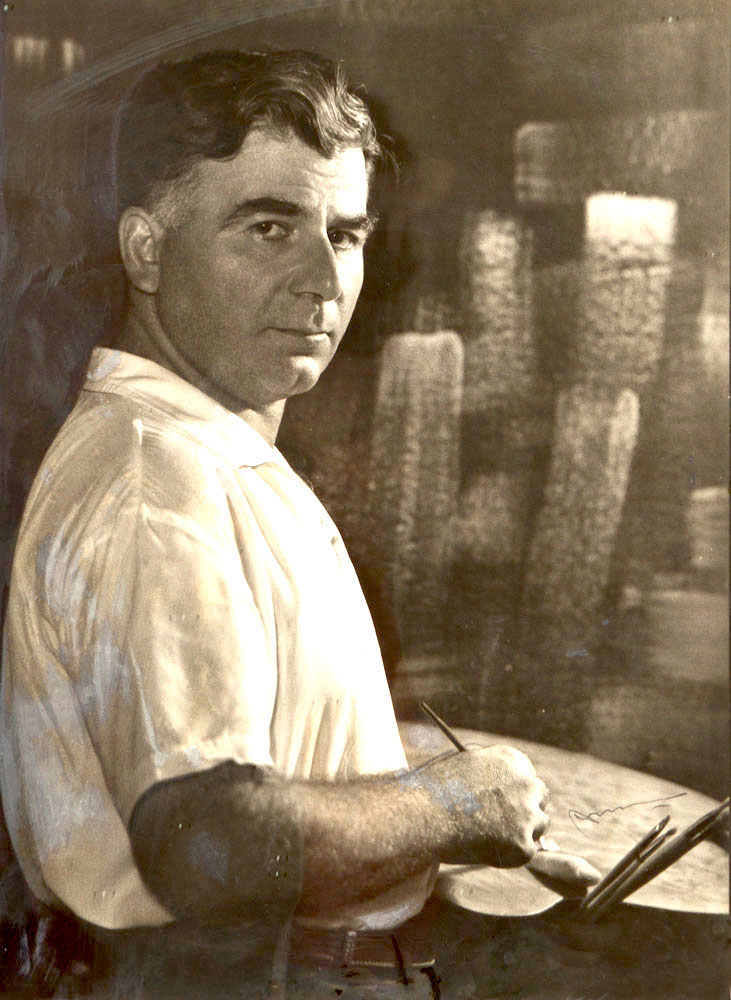

This essay focuses on an extraordinary Armenian artist, his harrowing survival of the genocide, his rise to fame in Cairo, and his creation of a unique style of abstraction.

Art historians have typically formed a chorus that teaches the history of abstraction like this: Just before and during the World War I era, several avant-garde artists emerged to create shockingly different new forms by which artists could express themselves. In Paris, Picasso and Braque broke out with cubism, quickly followed by Mondrian. In Moscow, Malevich created Suprematism, the ultimate hard-edge geometric abstraction. And in Munich, Kandinsky emerged as the father of Abstract Expressionism. Within these few short years a zeitgeist was sensed throughout the art world. American pioneers, too — particularly Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell — felt this explosive freedom of expression. When Europe was recovering after World War I it became clear that Paris would retain its title as capitol of the art world, lasting through the Roaring Twenties and even through the Great Depression. But the end of World War II changed everything. A parallel war had been won by a group of irascible young Abstract Expressionists in New York — led by Pollock, Rothko, DeKooning, and Kline. No sooner had Paris been liberated from the Germans than Picasso, Matisse, Breton, and Duchamp surrendered to the Americans. From that point on New York would be the epicenter of the art world.

…That’s the short easy version.

But a lens that focuses myopically on the war between the avant-garde of Paris and New York misses the wider narrative of multiple aesthetic modernities that developed in the several decades following World War I. For Armenian artists the matter is even more complex owing to the genocide of 1915 where more than 1.5 million people — seventy-five percent of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire — were massacred. Those not shot on the spot were sent on death marches through the Mesopotamian desert without food or water. Frequently, the marchers were stripped and forced to walk naked under the scorching sun until they dropped dead.

As a child Samsonian witnessed the murder of his parents and most of the members of his family. Soon thereafter, his older sister, Anahid, quickly shepherded him into a line of children being rescued by Greek nuns. But they became separated and he lost her, too. He was sent to a Greek orphanage in Smyrna (now Izmir), on Turkey’s west coast. Because he only knew his first name, the orphanage gave him a last name based on the place where they found him — Samsun — a major port on Turkey’s north coast on the Black Sea. His birth date was unknown, too. According to Samsonian’s vague recollections he assumed he was about three or four years old at the onset of the genocide, which would place his birth year in 1911 or 1912. In 1922, when Samsonian was about 10, the Turks ended their war with the Greeks by putting Smyrna to the torch in what has been called the “Catastrophe of Smyrna.” Once again, the child was on the run, escaping the fire and slaughter. He found temporary refuge in Constantinople, but within a year that major port would fall to the Turks, too, and become renamed as Istanbul. This time, Samsonian was whisked away to an orphanage in Greece founded by the American charity, Near East Relief — which is credited with saving so many Armenian orphans that the American historian Howard M. Sachar said it “quite literally kept an entire nation alive.

As a child Samsonian witnessed the murder of his parents and most of the members of his family. Soon thereafter, his older sister, Anahid, quickly shepherded him into a line of children being rescued by Greek nuns. But they became separated and he lost her, too. He was sent to a Greek orphanage in Smyrna (now Izmir), on Turkey’s west coast. Because he only knew his first name, the orphanage gave him a last name based on the place where they found him — Samsun — a major port on Turkey’s north coast on the Black Sea. His birth date was unknown, too. According to Samsonian’s vague recollections he assumed he was about three or four years old at the onset of the genocide, which would place his birth year in 1911 or 1912. In 1922, when Samsonian was about 10, the Turks ended their war with the Greeks by putting Smyrna to the torch in what has been called the “Catastrophe of Smyrna.” Once again, the child was on the run, escaping the fire and slaughter. He found temporary refuge in Constantinople, but within a year that major port would fall to the Turks, too, and become renamed as Istanbul. This time, Samsonian was whisked away to an orphanage in Greece founded by the American charity, Near East Relief — which is credited with saving so many Armenian orphans that the American historian Howard M. Sachar said it “quite literally kept an entire nation alive.

Why didn’t Samsonian know his birth date? The following poem, “3 or 4,” by his grandson, Alan Semerdjian, shines some light on the matter. This poem is an excerpt from the series, “Fragments of a Composition with Grandfather” from Semerdjian’s book of poetry, In the Architecture of Bone (2009).

3 or 4

The memory stain attaches itself and darkens on the pale

formless sheet, a hole increasing its size larger and larger until

it assimilates the boundaries and becomes itself formless.

All memory. Occupies the entire. — Theresa Hak Kyung Cha [1951-1982]

1915.

He dreams about remembering

when he was born, but he can’t.

How can anyone dream for nothing?

How can anyone remember?

I ask my friends, a mother’s touch

in the womb, the fear of running

or slow march, incessant heat…

all that violence as a newborn?

No, the closet would’ve been too dark,

the mind too fresh. No one remembers

how they were born and the color

of the scarf they were born into,

the quiet under a bed, the smell

of leather, soldier’s shoes, footsteps,

the taking away.

It doesn’t work like that.

Nothing works like that.

He doesn’t remember

works like that. But memory doesn’t

work like that. It doesn’t sit still

till its suddenly ripped open,

and then you’re born with a war

at the other end of an umbilical cord.

Memory doesn’t work like that.

It starts later. When you are born again.

He must have been 3 or 4 when it happened,

that’s what I think. He must have been –

still is – speechless about it, stained,

surrogate, and reposed, all

question marks and stone, but still,

how can anyone forget?

Any understanding of Samsonian’s approach to modernism requires careful consideration of the impact of his early years because his art is inseparable from the anguish he experienced. In 1927, when he was a teenager, he was transferred to Cairo, Egypt, then a cosmopolitan city hosting a sizable portion of the Armenian diaspora. There he lived with thirty-two other children on the top floor of the Kalousdian Armenian School. Upon graduating in 1932 he won a scholarship to attend the Leonardo da Vinci Art Institute — an Italian art school in Cairo — where he won first prize in final examinations among one hundred students. He found work with an Armenian lithographic printer and he returned to the Kalousdian Armenian School to teach drawing. In 1939 he married one of his students, Lucy Guendimian.

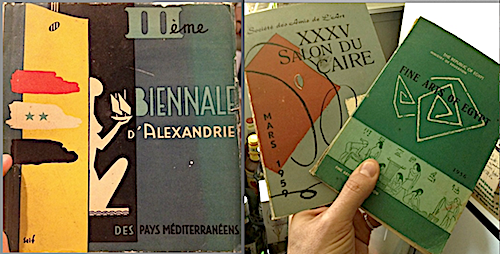

The Cairo in which Samsonian matured as an artist was home to many prominent art collectors after World War I. In this receptive environment Samsonian exhibited widely and won many awards. Beginning in 1937 and for the next thirty years he exhibited annually at the prestigious Le Salon du Caire hosted by the Société les Amis de l’Art (founded in 1921). After World War II he hit his stride as a modernist in Cairo, counting among his peers other artists of the Armenian diaspora such as Onnig Avedissian, Achod Zorian, Gregoire Meguerdichian, Hagop Hagopian, and Puzant Godjamanian.

In 1950s Samsonian made extended trips to visit the great art museums of Italy, Paris, and London. The experience proved to be a catalyst for the development of his own style of figurative cubism, boldly structured and colored.

In 1960, nearly a half century after he lost his family he was shocked to discover his sister, Anahid, was living just a few hours to the north in Alexandria. The emotional reunion also revealed his real family name: Klujian.

In 1961 Le Salon du Caire gave Samsonian a solo exhibition of his works created since 1950. It was with great media coverage that for the first time in history an Egyptian Minister of Culture personally opened an exhibition by an Armenian artist. That year, the Salon followed up by sending him on a trip to Paris and London to study contemporary art. Over the years the Salon awarded him seven gold medals at their annual exhibitions.

During the 1960s Anwar Sadat [1918-1981], then President of the National Assembly in Egypt (he became President of Egypt in 1970), acquired a painting by Samsonian and wrote him a letter, commending him as one of the country’s great artists. Samsonian would leave his adopted country in 1968, at the urging of his daughter, and resettled near her in New York. But he first spent two months in Athens where he had been invited to present a solo exhibition. Parnassos, the city’s cultural yearbook, called the exhibition “The best cultural undertaking of the year.”

Samsonian continued painting and drawing, never slowing down. But in this new phase of life he felt he had little more to prove. For decades he had received serious critical recognition and won many awards. Even though an Armenian association published a monograph on him in 1978 his heart was simply not committed to promoting his work through galleries. Samsonian, the painter whose work had become inseparable from his story, slipped away into the quietude of old age and passed away in 2003.

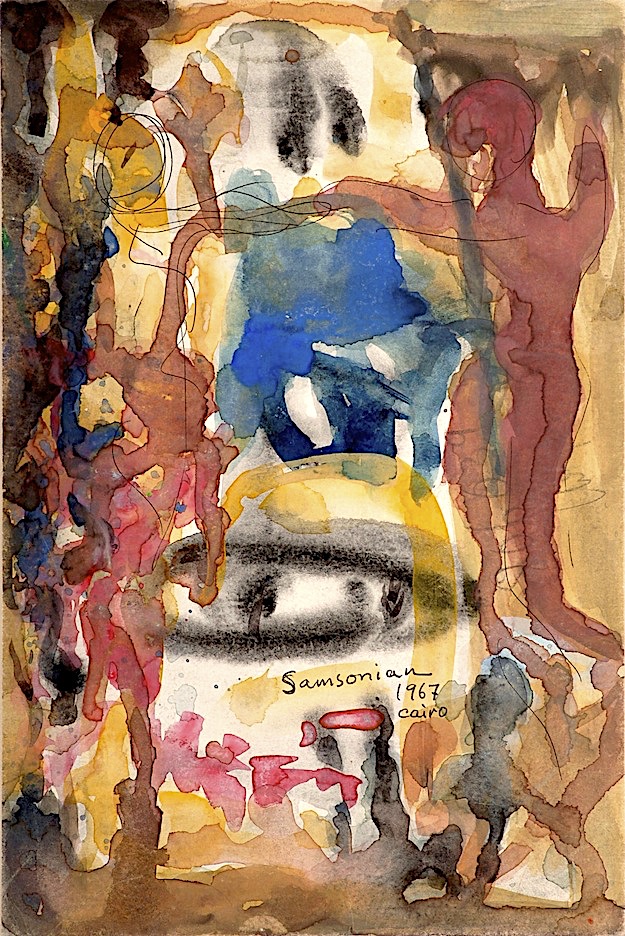

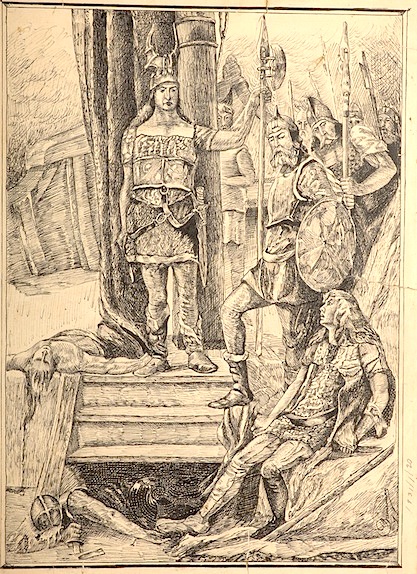

Samsonian presents compelling affinities and contrasts with Arshile Gorky [1904–1948]. While Gorky was playing an influential role as a progenitor of the Abstract Expressionists in New York, Samsonian was building his career in Cairo. Unlike Samsonian, Gorky never recovered from the horror of the genocide in Turkey where he was a traumatized child witnessing his mother starve to death in Yerevan. He had great difficulty ascertaining his own identity and waffled about his place and date of birth. Claiming that he was a relative of Maxim Gorky, he took the great Russian writer’s name. Samsonian was a survivor who also carried with him the burdening question of his personal identity. But unlike Gorky, who was so depressed he committed suicide, Samsonian celebrated life by continuing to create paintings that are bold and colorful reactions to the genocide he escaped. They are affirmations of survival — revelations of an indomitable spirit. Like many of the artists of the Armenian diaspora his early work reflected the bravura brushwork of Impressionism and the freedom of color of Fauvism. But as he matured and became famous in Cairo he was among the few who, having thoroughly absorbed the cubist principles of Braque and Picasso, developed a new style of cubism that is distinctly Armenian. M. Haigentz, author of a monograph on Samsonian published in 1978, described how the artist’s distinct style evolved to reflect symbolism, humanism, and faith:

There began to appear in his work basic aesthetic tendencies stressed through bold and strong lines. The study of generalized forms served as a basis for presenting his subjects in one unified harmonious cast. He put in each line his self and seal and made them articulate through the language of the geometrician and designer-painter, endowed the expanses of color and linear figuration with pure and ungarnished values, and made them come alive in the harmonious music of color. There they are, human sorrow and affection, which effortlessly are veiled with cheerful and live colors. Those “Samsonian” colors are but emanations of his subconscious, just as amidst the thorns of life he had loved life as a rose. He was bound with an indescribable affection for all his works and felt desolate whenever obliged to part with the “luckier” ones among them.

Samsonian’s style became the ideal backdrop on which to cast both figurative and non-objective imagery — and it seemed to serve as the perfect tool for articulating the complexity of being an orphaned genocide survivor. Some of his most famous paintings feature figures merged into cubist backgrounds, often subtle in their revelation of a cross — one that all of us must ultimately bear in one way or another.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Bibliographic Sources

Haigentz, M. Simon Samsonian: His World Through Paintings. (New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union, 1978, p.10)

http://www.armenian-genocide.org/ner.html

http://www.egy.com/community/04-12-16.php

Museum Collections

The National Art Gallery, Yerevan, Armenia (owns 25 oils)

Museum of Modern Art, Cairo, Egypt (owns 12 oils)

La Musée Arménien de France

Collection of the The Mekhitarist Fathers’ Monastic Order, Vienna, Austria

Hecksher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York

Armenian Museum of America, Boston, Massachusetts

Select Solo Gallery Exhibitions in the U.S.

Armenian General Benevolent Union, 1968

Kar Gallery of Fine Art, Toronto, 1969

Lynn Kottler Gallery, New York, 1972

Armenian Museum of America, Boston, 2015 http://www.armenianmuseum.org/collection/the-art-of-simon-samsonian/

Survival and Creation

-

DETAILS

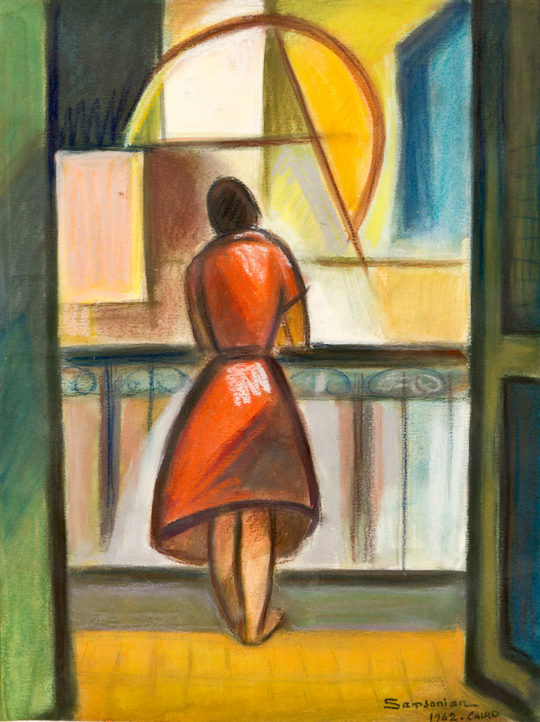

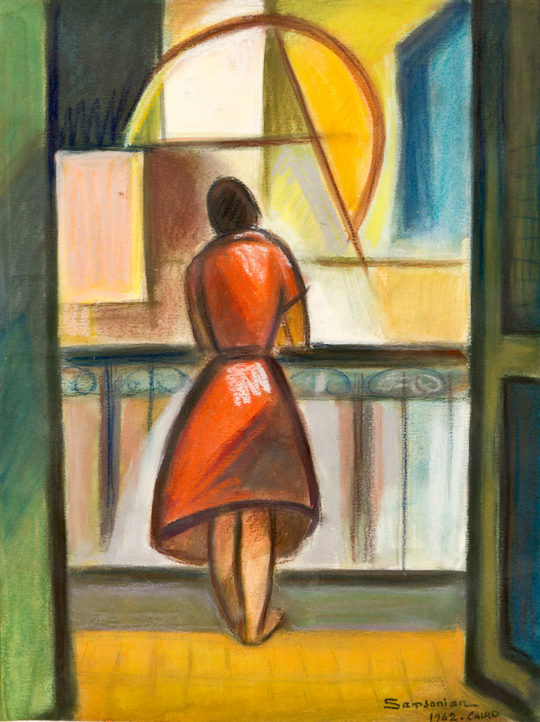

DETAILSBalcony in Cairo, 1962

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBeach Scene, Cairo, 1949

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSChristmas Dinner, Cairo, 1947

17 x 12 inches (43.18 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCouple at the Beach, Cairo, 1949

12 x 9.5 inches (30.48 x 24.13 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEyes, 1963

4.5 x 8 inches (11.43 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLiving Room, 1967

15.5 x 12 inches (39.37 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSManhattan No.2, 1980

34 x 48 inches (86.36 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

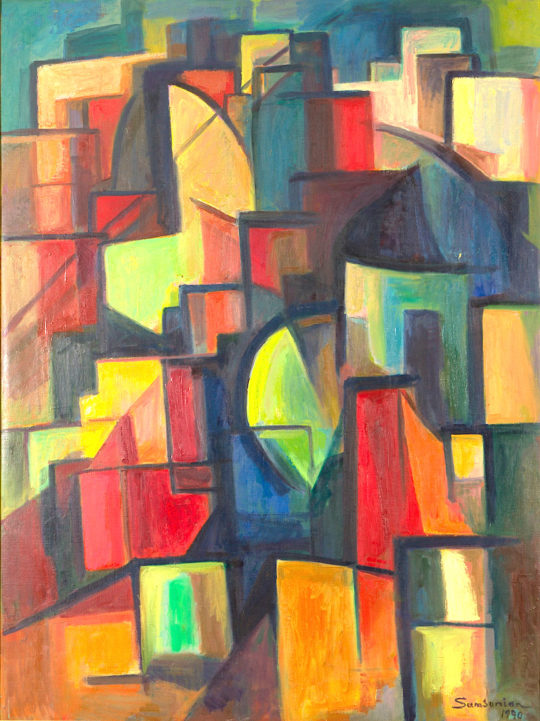

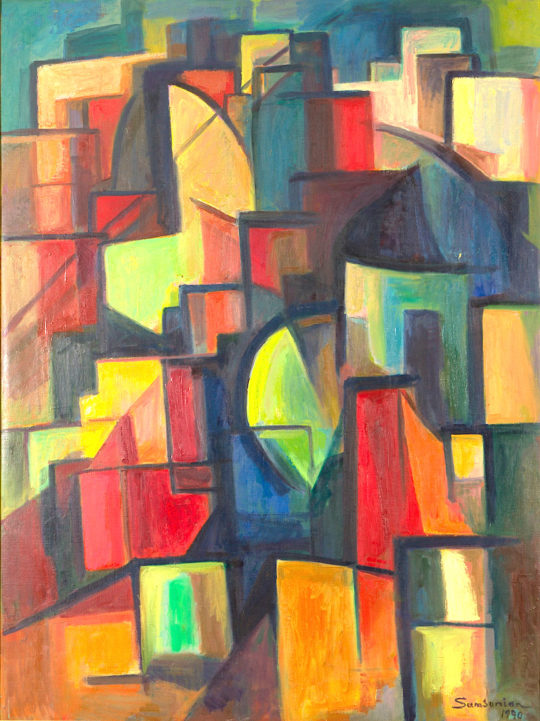

DETAILSManhattan No.3, 1990

34 x 48 inches (86.36 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOcean Overlook, Cairo, 1949

9.5 x 7.5 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPreparation, 1948

12 x 10.5 inches (30.48 x 26.67 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Memory of the Valley, 1961

9 x 6 inches (22.86 x 15.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Opening, 1968

6 x 4 inches (15.24 x 10.16 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Violincellist, 1957

31 x 47 inches (78.74 x 119.38 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTogether, Cairo, 1967

7.5 x 11 inches (19.05 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

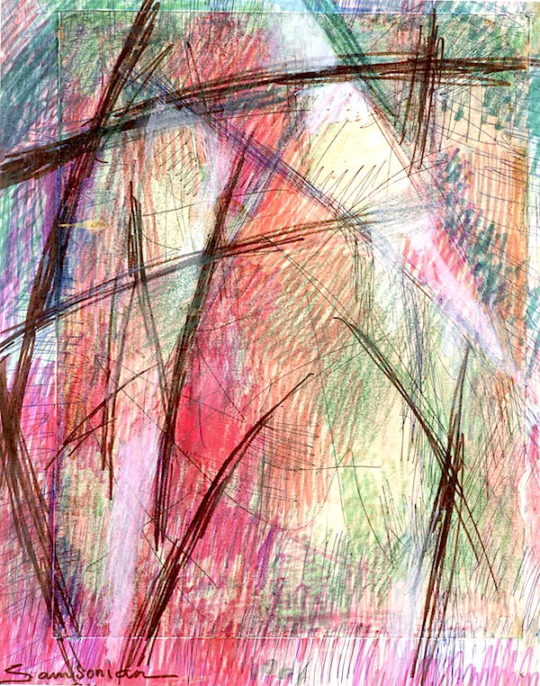

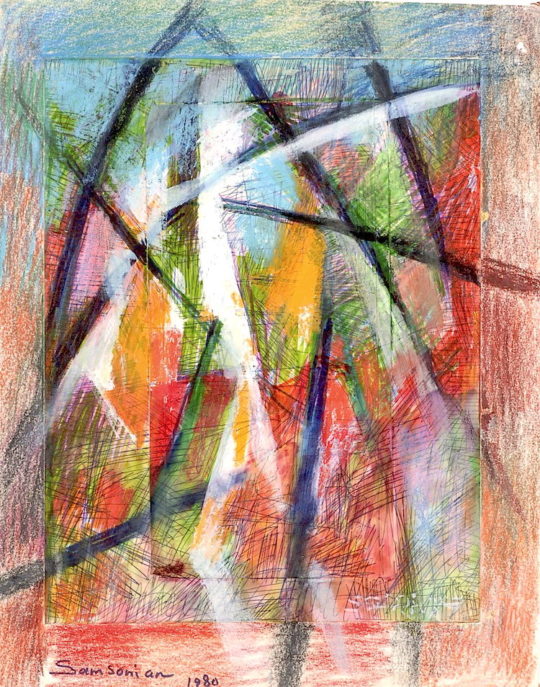

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction, New York City), 1980

10 x 14 inches (25.4 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

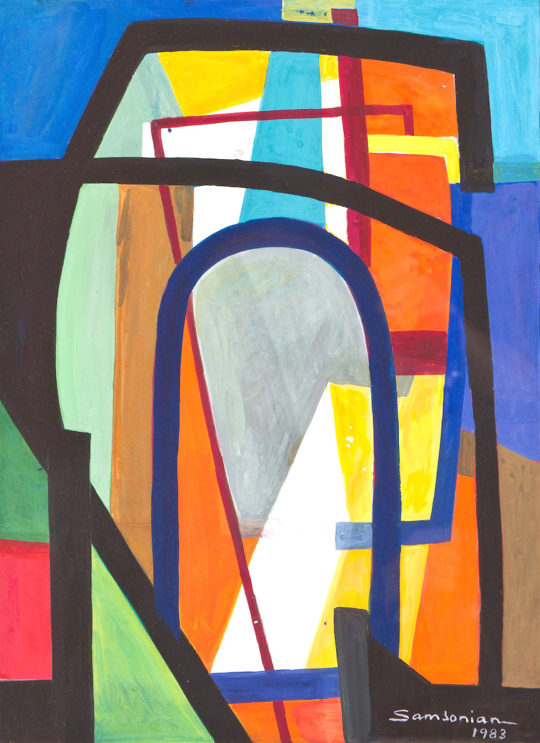

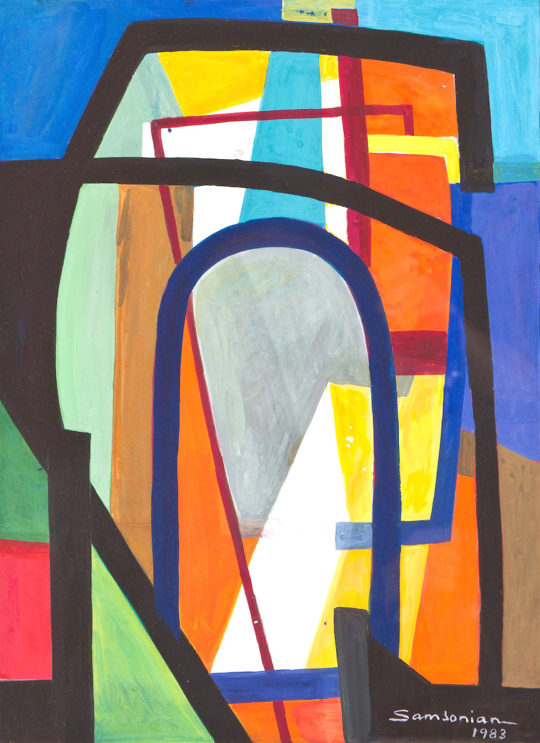

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction, New York City), 1983

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

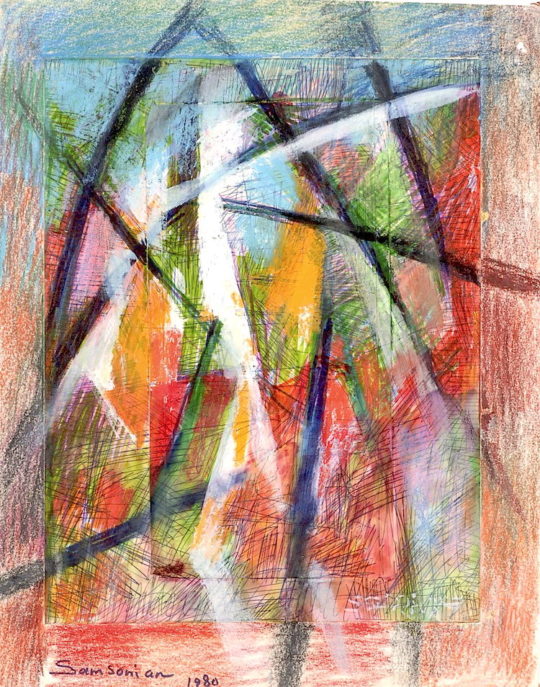

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction, New York), 1979

13 x 16 inches (33.02 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

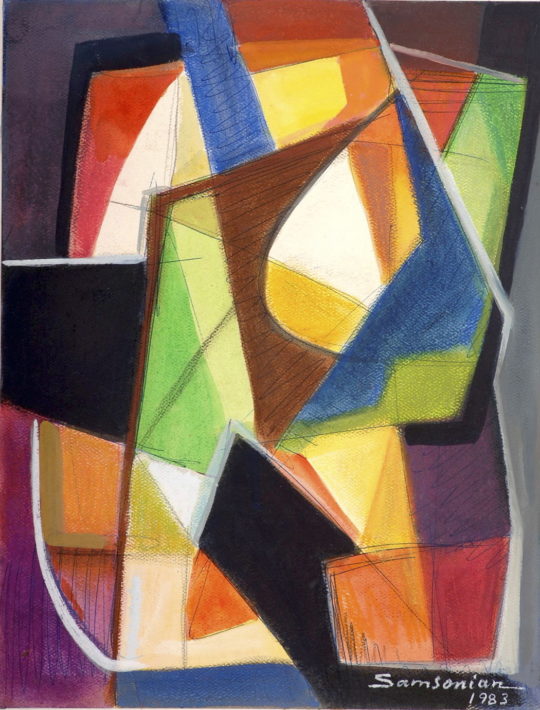

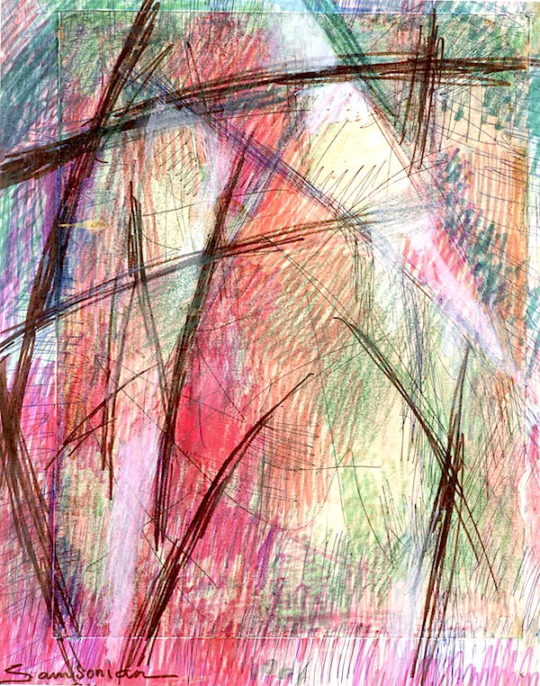

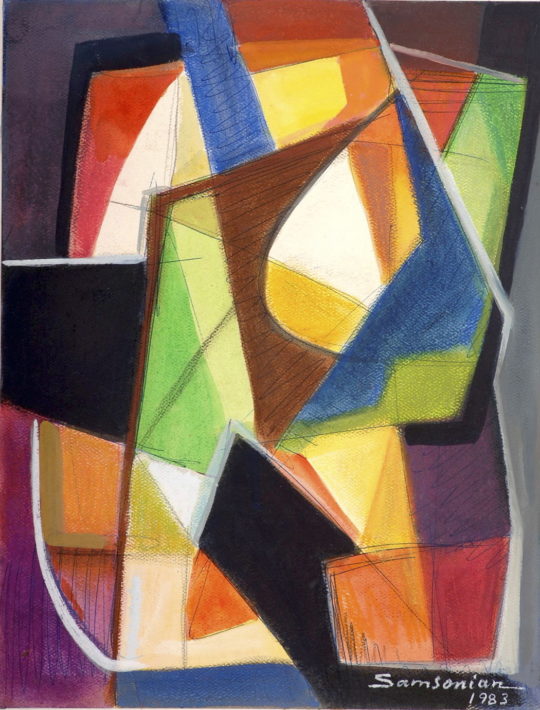

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1983

14 x 19 inches (35.56 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1979

11 x 13 inches (27.94 x 33.02 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1998

9 x 12 inches (22.86 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1980

10.5 x 13.5 inches (26.67 x 34.29 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1983

10 x 13 inches (25.4 x 33.02 cm) -

DETAILS

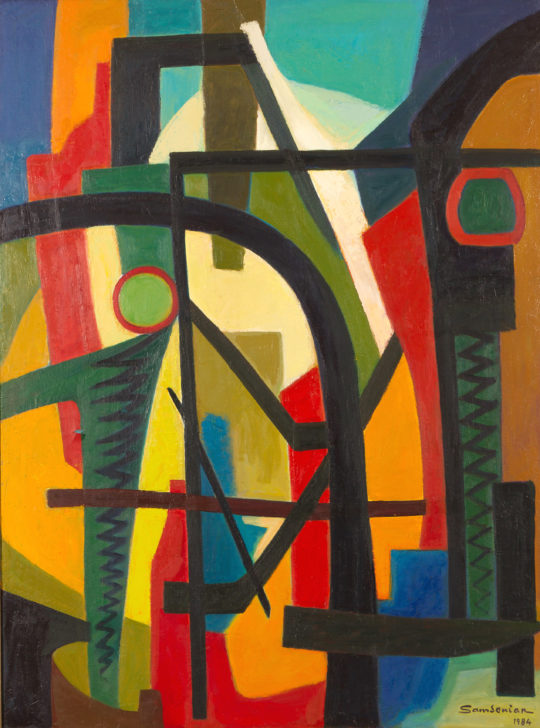

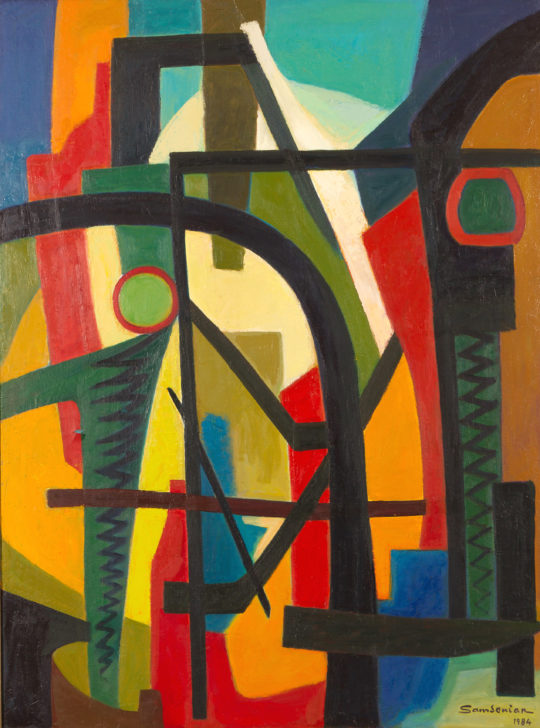

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1984

30 x 46 inches (76.2 x 116.84 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1983

14 x 20 inches (35.56 x 50.8 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSBalcony in Cairo, 1962

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBeach Scene, Cairo, 1949

4.5 x 5.5 inches (11.43 x 13.97 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSChristmas Dinner, Cairo, 1947

17 x 12 inches (43.18 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCouple at the Beach, Cairo, 1949

12 x 9.5 inches (30.48 x 24.13 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEyes, 1963

4.5 x 8 inches (11.43 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLiving Room, 1967

15.5 x 12 inches (39.37 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSManhattan No.2, 1980

34 x 48 inches (86.36 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSManhattan No.3, 1990

34 x 48 inches (86.36 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOcean Overlook, Cairo, 1949

9.5 x 7.5 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPreparation, 1948

12 x 10.5 inches (30.48 x 26.67 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Memory of the Valley, 1961

9 x 6 inches (22.86 x 15.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Opening, 1968

6 x 4 inches (15.24 x 10.16 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Violincellist, 1957

31 x 47 inches (78.74 x 119.38 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTogether, Cairo, 1967

7.5 x 11 inches (19.05 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction, New York City), 1980

10 x 14 inches (25.4 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction, New York City), 1983

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction, New York), 1979

13 x 16 inches (33.02 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1983

14 x 19 inches (35.56 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1979

11 x 13 inches (27.94 x 33.02 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1998

9 x 12 inches (22.86 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1980

10.5 x 13.5 inches (26.67 x 34.29 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1983

10 x 13 inches (25.4 x 33.02 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1984

30 x 46 inches (76.2 x 116.84 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (Abstraction), 1983

14 x 20 inches (35.56 x 50.8 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

No Events Found.