“One small grain of sand, unstained”

In 1937 Ashlock entered the freshman class at the University of Washington in Seattle with every good intention of following a traditional education. But after his sophomore year he quit, compelled to pursue his passion for painting. His mother was supportive, but his father’s hostility to what he perceived as an insecure and unmanly calling never diminished. Ashlock moved to San Francisco and spent two years at the California School of Fine Arts. Walking long distances to find his sites, and carrying his paints and brushes around in a shoebox — he would battle financial stringencies all his life. Ashlock’s earliest works are largely of scenes around the Bay Area, painted in watercolor en plein air in the style of the Regionalists. He often spent early mornings at the racetrack, drawing the horses as they exercised, but the trainers, afraid of flapping papers, demanded he maintain a buddha-like composure as he drew, which perhaps contributed to the apparent simplicity in his lifelong working-habits.

Though Ashlock exhibited his works from time to time, he did so more out of what he perceived to be a social obligation — as a faculty member — and never actively promoted his work. He never hustled the galleries and museums but remained a classic example of the independent artist, quite wishing someone would notice but never exerting himself to bring that notice about. And perhaps because of that absence of professional fulfillment, and the unhappiness of a personal relationship in which he and his wife shared such different goals, Ashlock began to feel trapped, tormented, and prone to fits of anger. He was nearly forty, but a mature, consistent style of painting had not yet emerged. He described himself as an irascible character, at odds with the world. In 1957 he took advantage of an offer to ride East, packed his paintings onto the car-rack, and left his wife and two children to move to New York City.

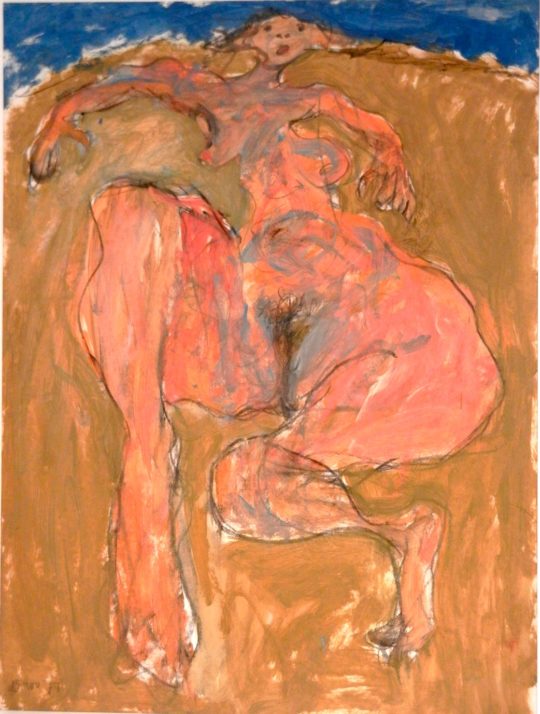

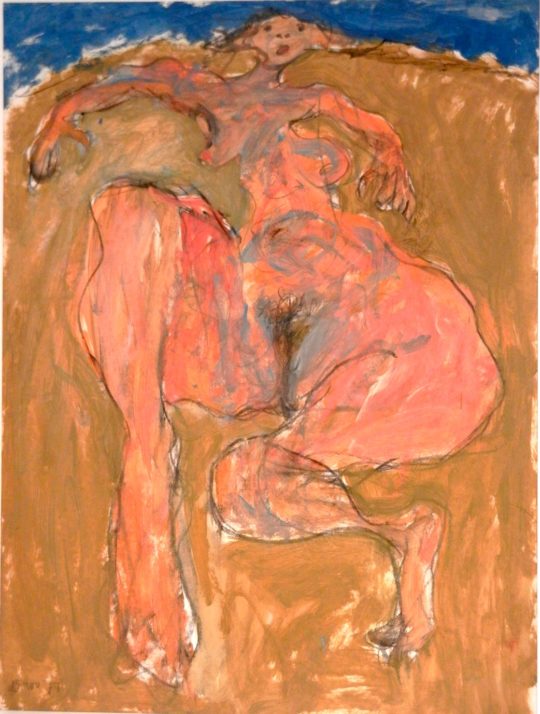

His first years in Manhattan found Ashlock settled into tiny apartments, first in Chelsea, later in Greenwich Village. He complained about the lack of space. “Kline was painting his big black-and-whites, but it wasn’t easy for me to paint [large] . . . there was furniture, paint pots on the floor, no space, and no sense of comfort or convenience.” Nor, despite his dreams, did his personal relationships ever finally provide sustained emotional support. He could paint women; the female form was an endless source of inspiration for him, but as for living with the flesh-and-blood creature herself . . . gradually, he began to derive his comfort from whisky, cigarettes, cats, and the New York Times. As he settled into drinking at the Cedar Tavern, Ashlock soon became friendly with many of the abstract artists of the first generation of the New York School, including Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. They were all still mourning the death of Cedar Tavern regular, Jackson Pollock. Ashlock recalled the summer of 1956 when, the day he arrived on his first exploratory visit to New York, the newspaper headline of Pollock’s death leapt out at him on the day he arrived.

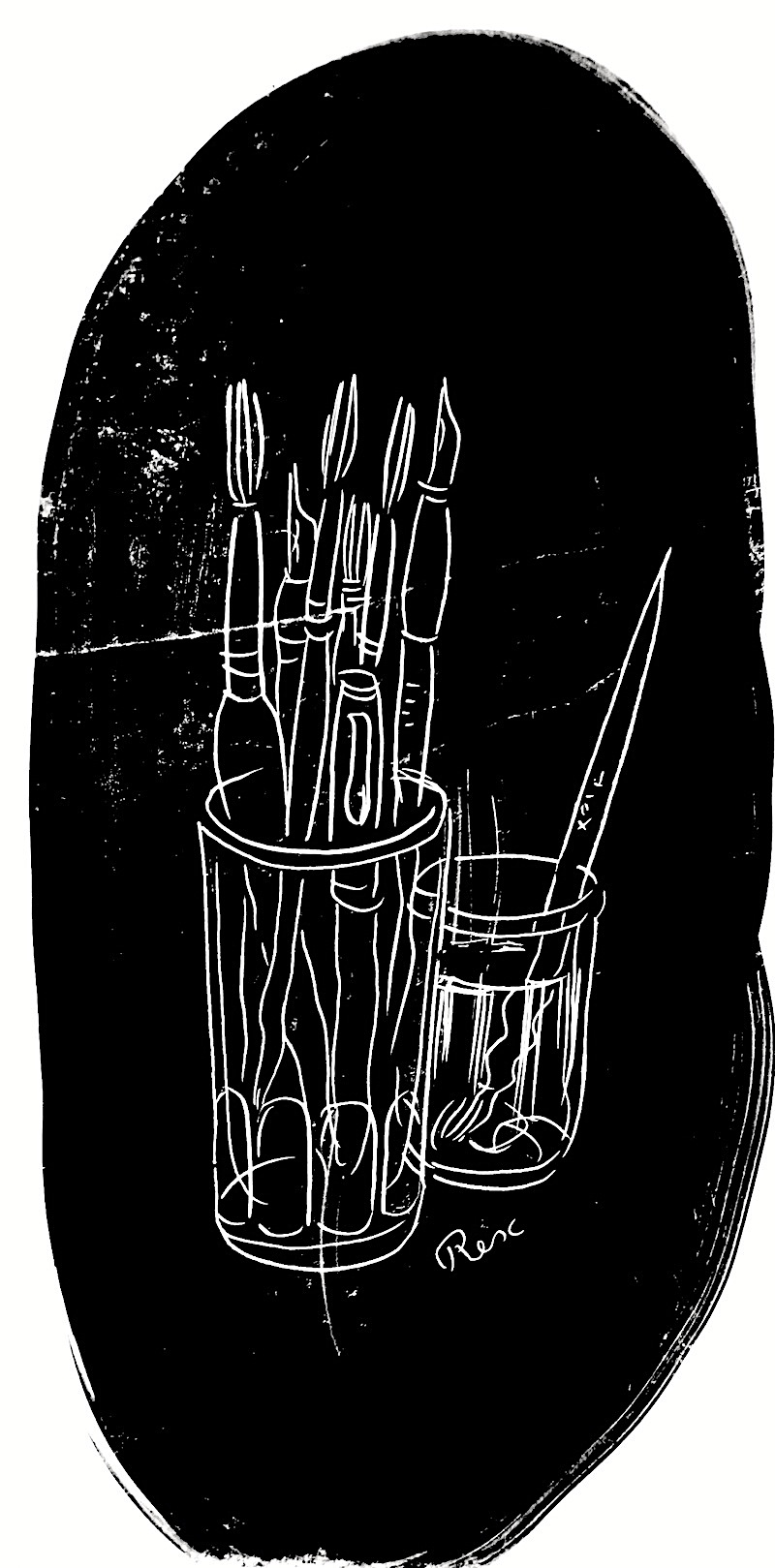

Although Ashlock soon came to know many artists in New York (like “Kostas the Greek,” who had a photographic memory of where “every painting was to be found in every European museum”) it appears he had few lasting friends. Increasingly, he began to derive his comfort from whisky, cigarettes, cats, and the New York Times. And while his Ab-Ex friends were all painting large, Ashlock was restricted by his small apartments, leaving him impatient and frustrated. “Kline was painting his big black-and-whites, but it wasn’t easy for me to paint large… there was furniture, paint pots on the floor, no space, and no sense of comfort or convenience.” Nor, despite his dreams, did personal relationships ever provide sustained emotional support. The female form was an endless source of inspiration for him, but as for living with the flesh-and-blood creature herself… Nevertheless, he survived on an erratic income by securing illustration jobs at the New York Times, The New Yorker, and other magazines. From 1963 to 1970 he also taught a painting class at the Museum of Modern Art. Later, he taught at The Artists’ Workshop in New York and at the Princeton Art Association. In between he collected unemployment insurance.

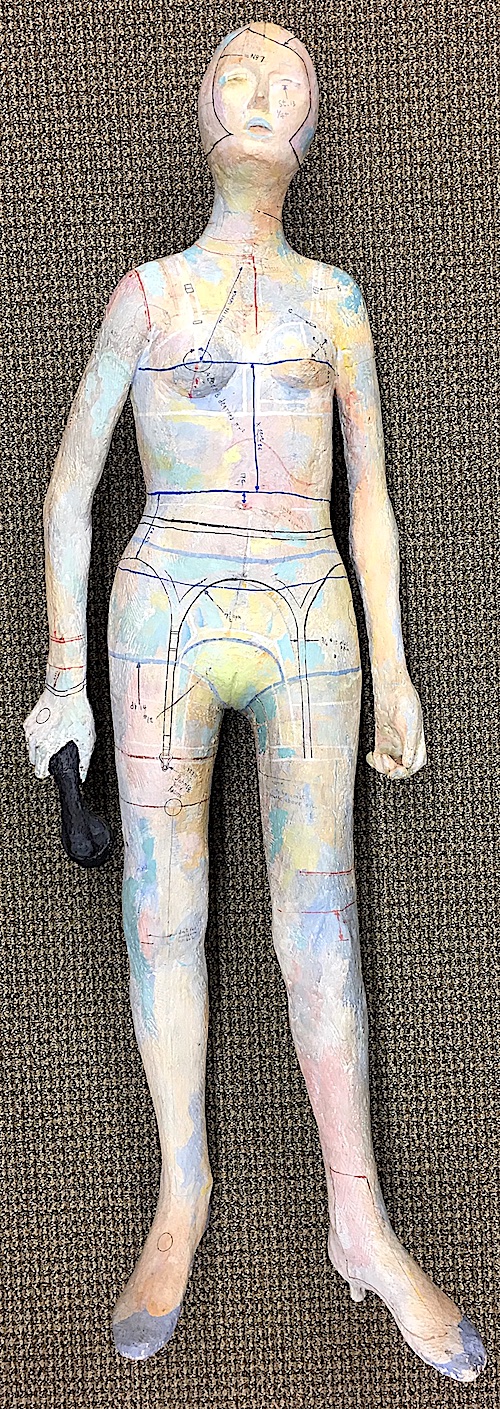

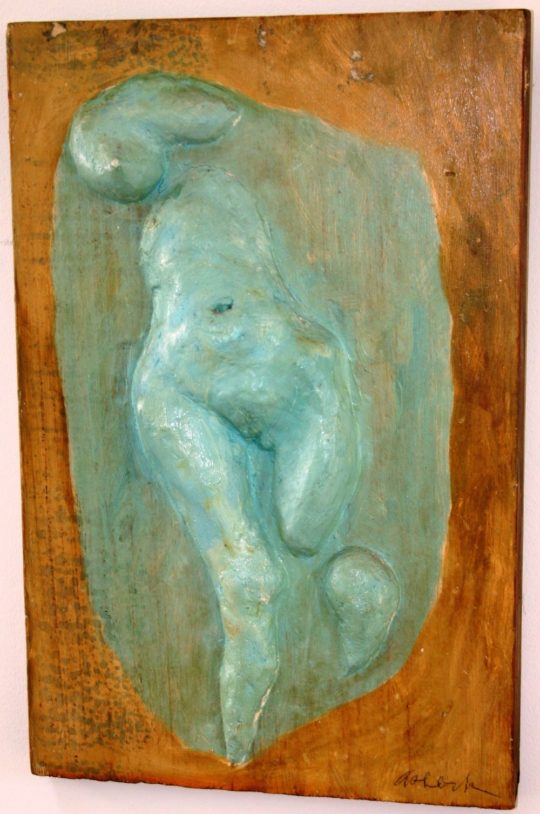

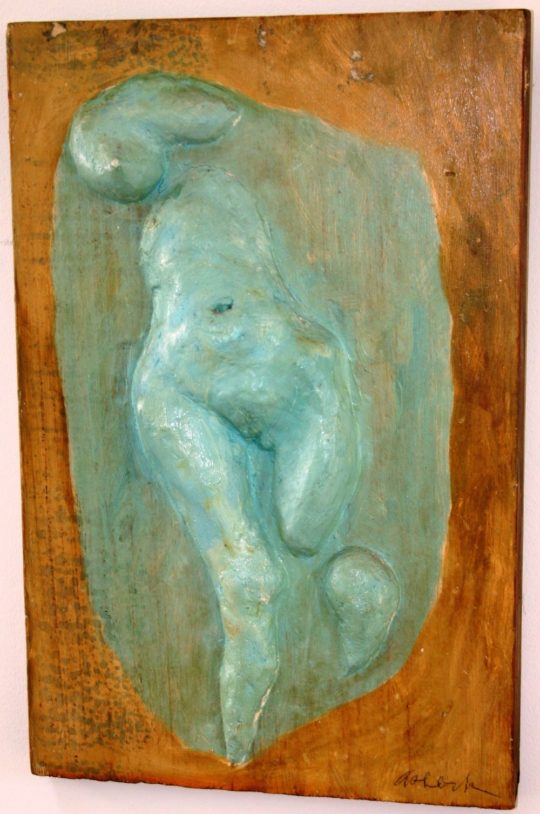

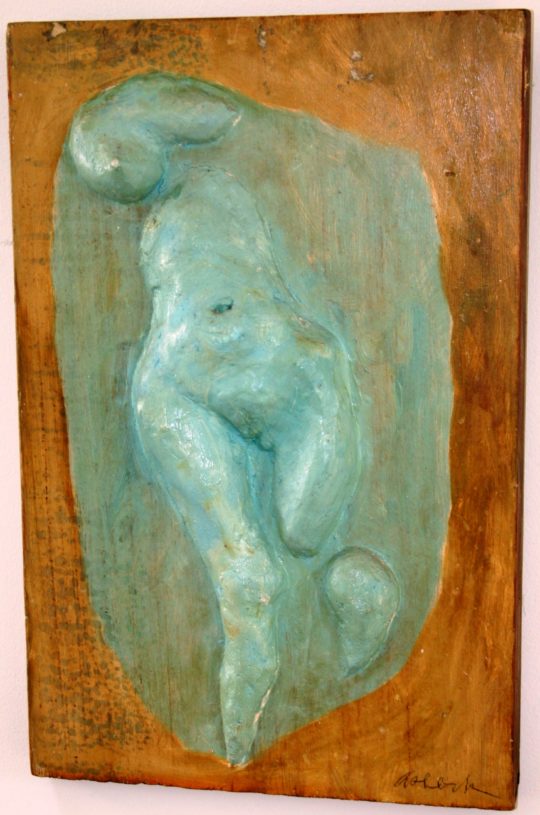

In sculpture it was not surprising that Ashlock focused on the female form. Inspired by some of the polychrome wood-sculptures of Elie Nadelman [1885-1946], he began a series of female nudes in painted plaster. Years later, one of Ashlock’s students, Nathan Oliveira — who also became a colleague and fellow teacher — began a similar series of painted nudes for which he is now well-known.

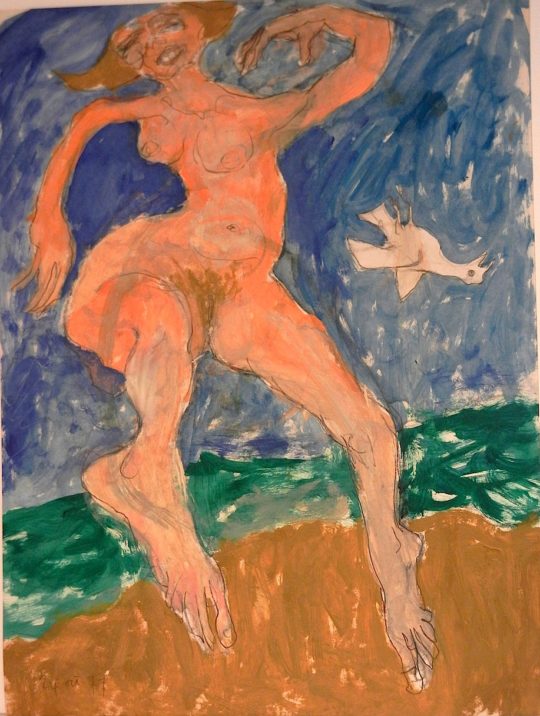

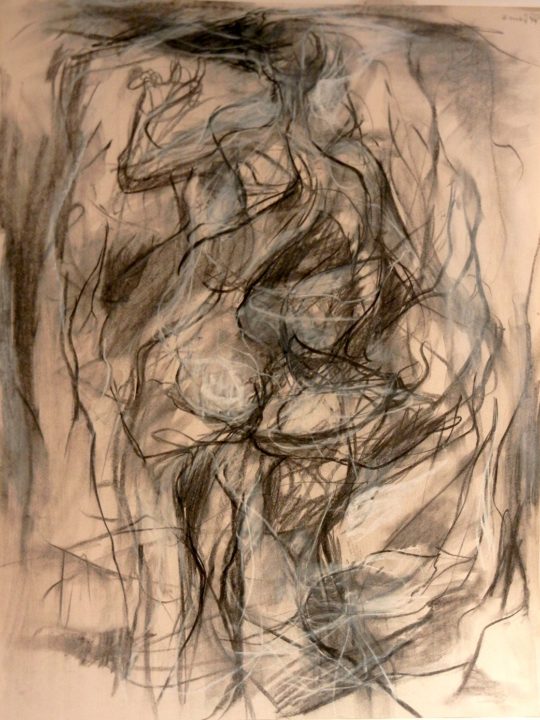

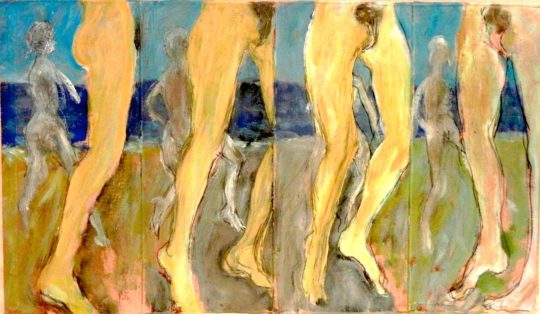

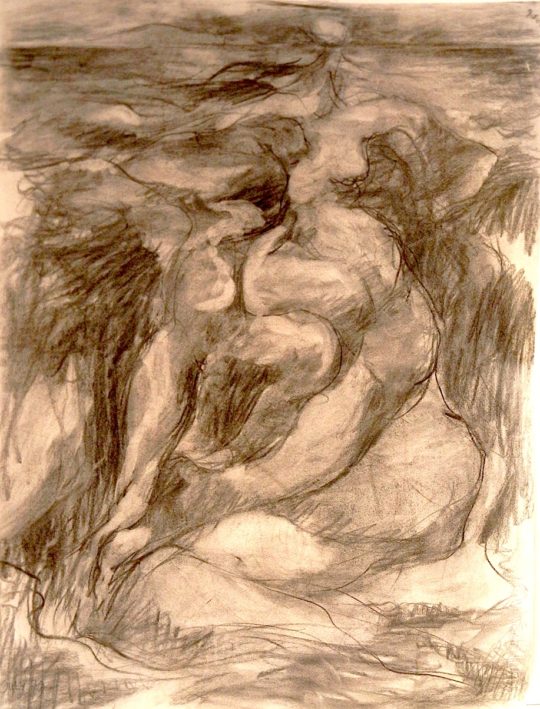

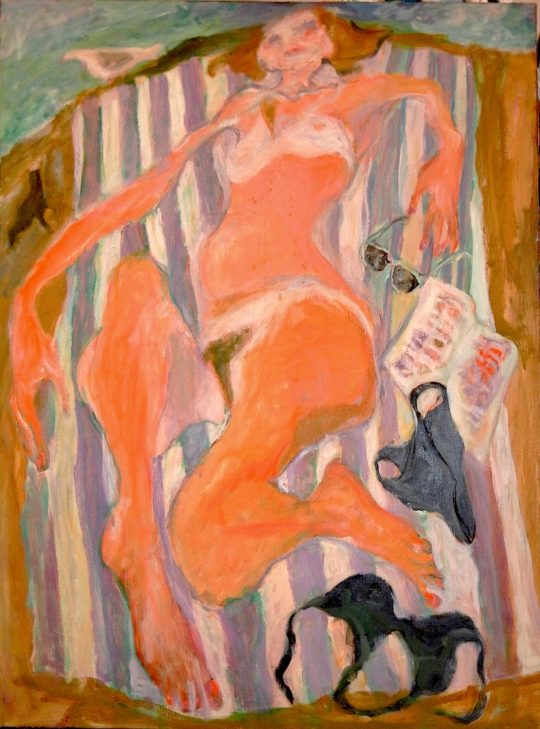

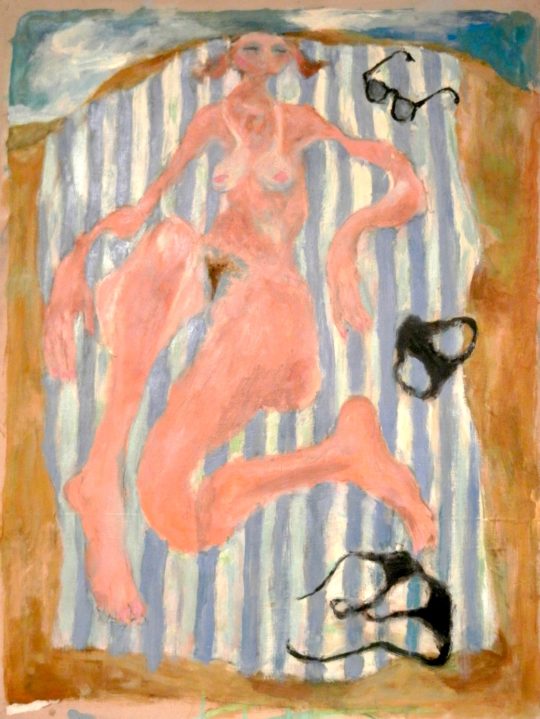

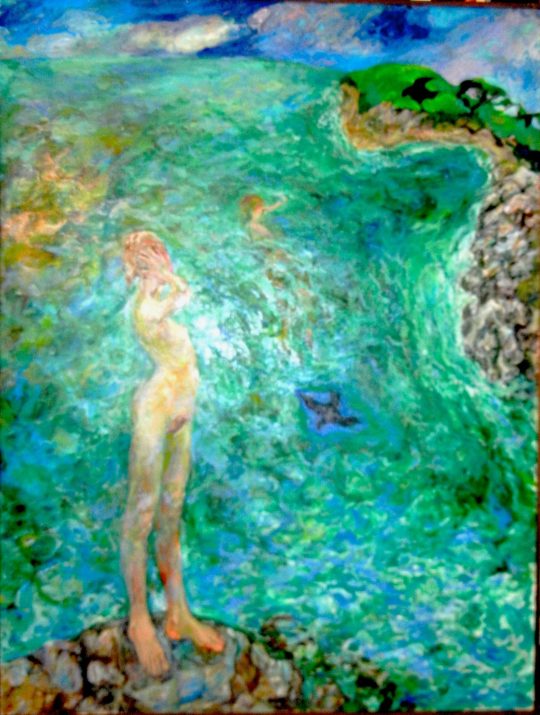

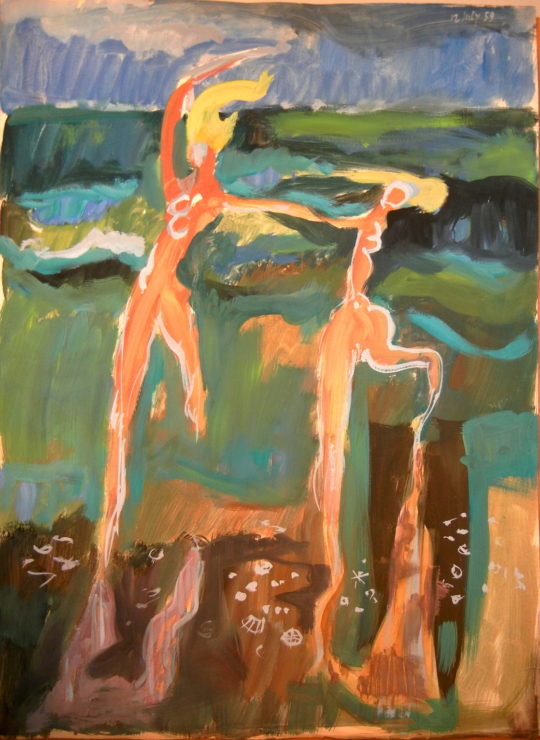

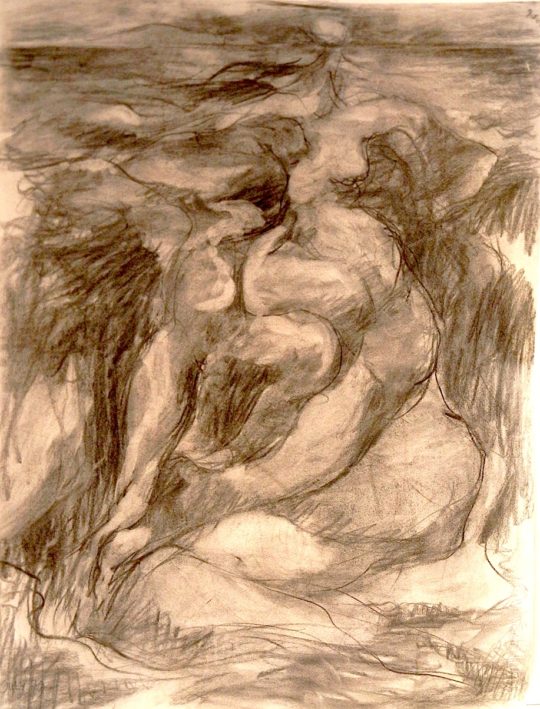

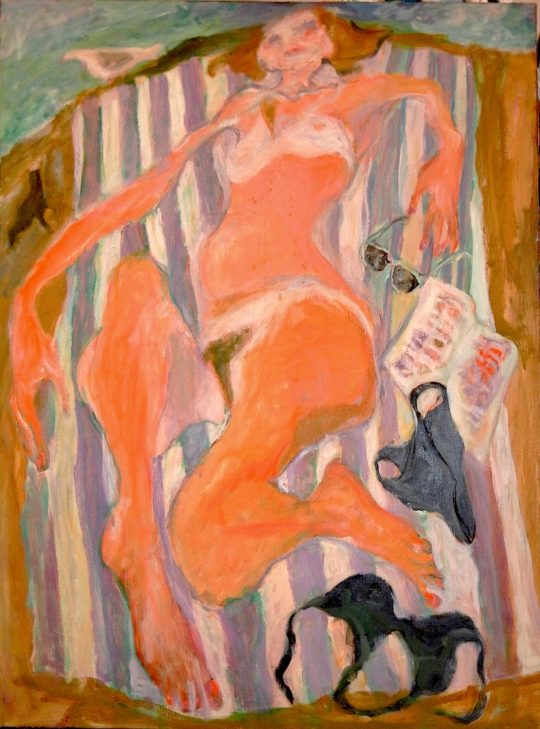

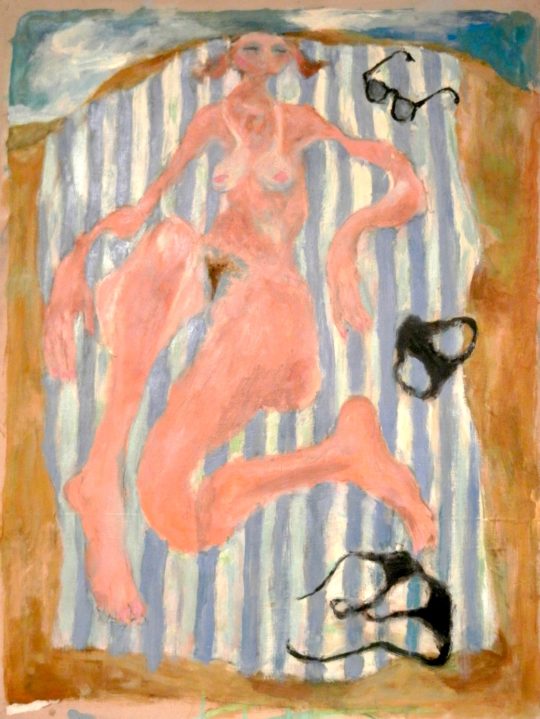

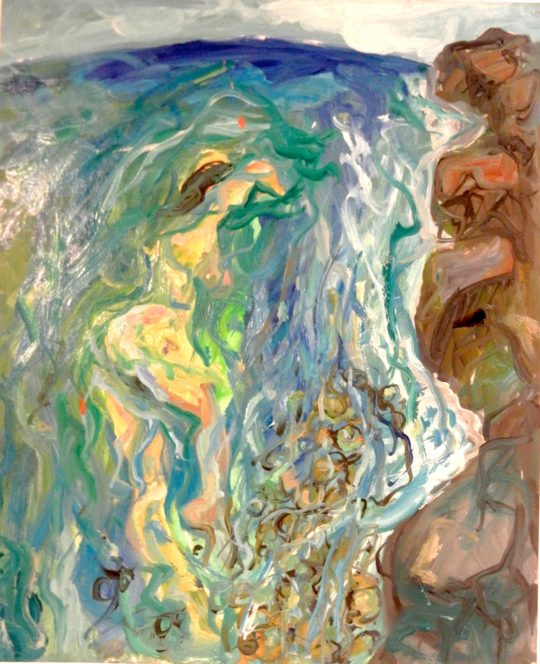

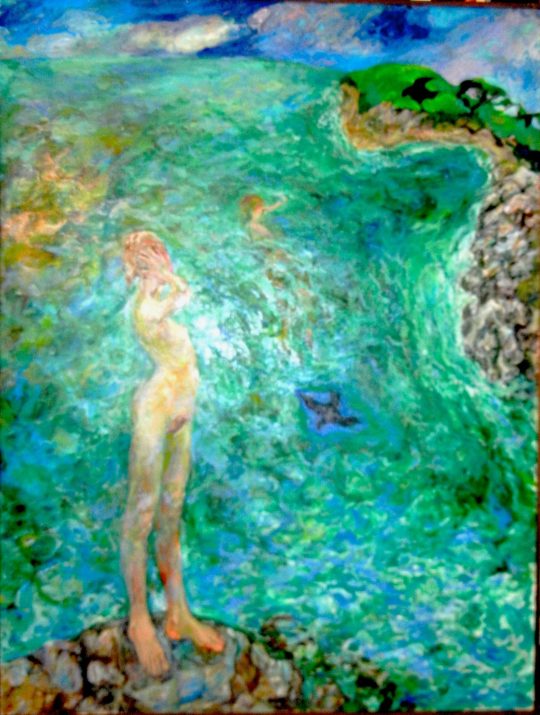

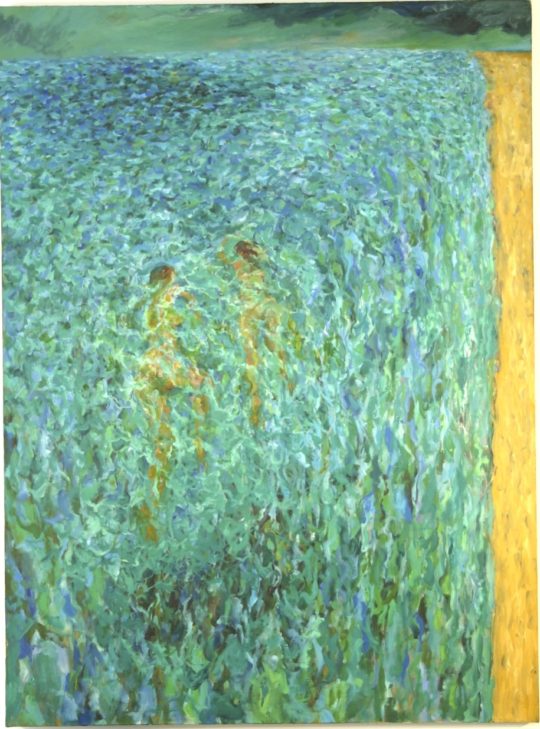

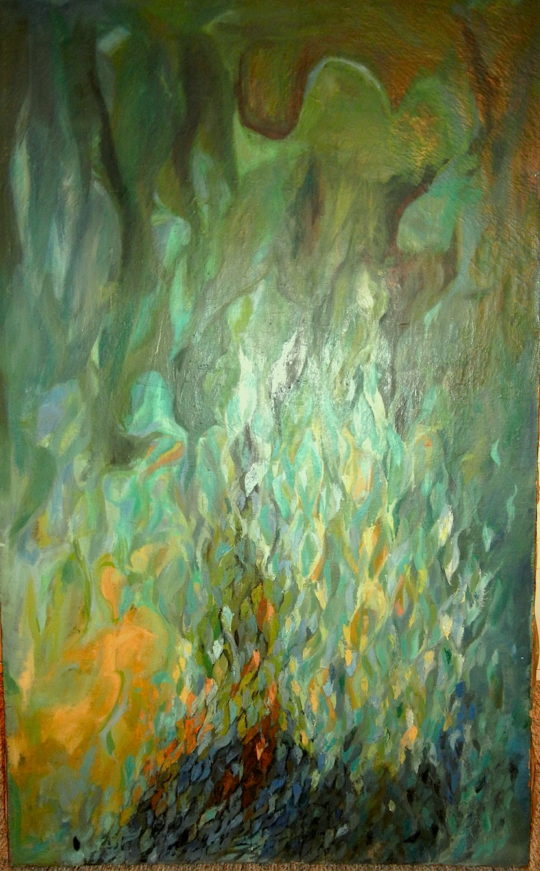

It is these mature works, rooted in figurative expressionism, which bear his unique stamp. Like Cedar-tavern acquaintance, Willem de Kooning, Ashlock was fascinated by the female figure and never abandoned it as his primary source of inspiration. “I was influenced by de Kooning and Oskar Kokoschka and German Expressionism, but I didn’t want to go abstract. I wanted to represent something.” Ashlock pointed to Mondrian as one who was more interested in spiritualism than appearance, so that his paintings conveyed an underlying force. “Mondrian may not be so concerned with the look of things as with spatial relationships, patterns, and relations between lines and color. I find it hard to be totally non-representational. The look of things is important to me.” He was also impressed by the leading English figurative painters, Francis Bacon [1909-1992] and Lucian Freud [b.1922]. He lamented, “We haven’t produced anyone here in this country like Freud or Bacon.”

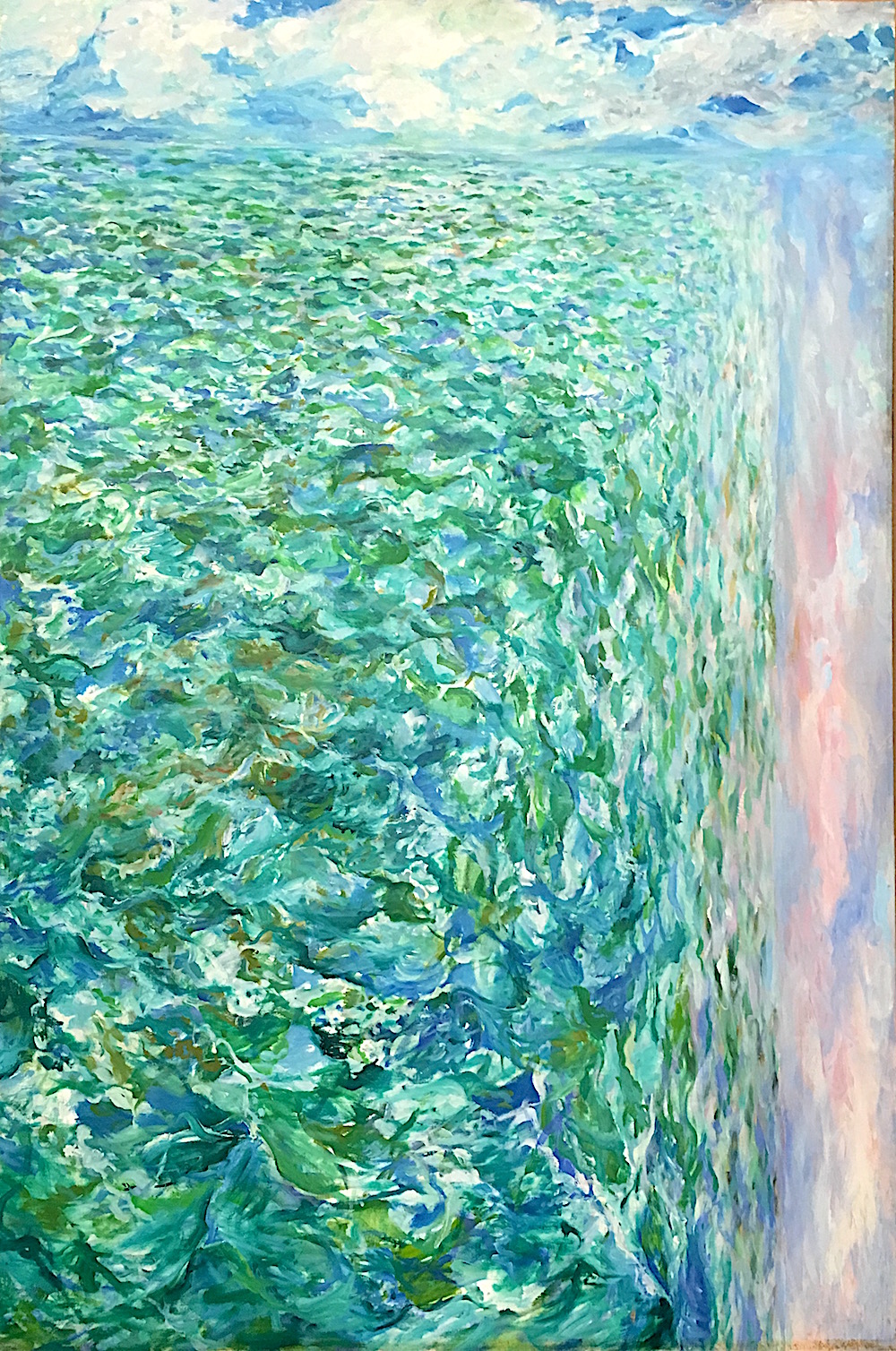

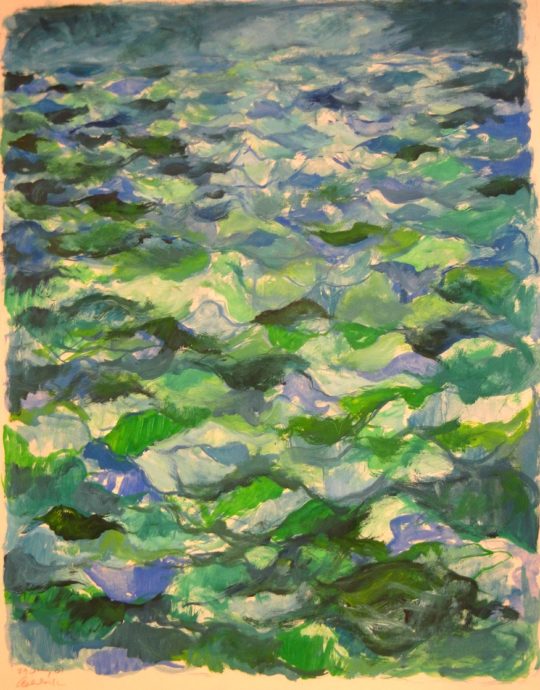

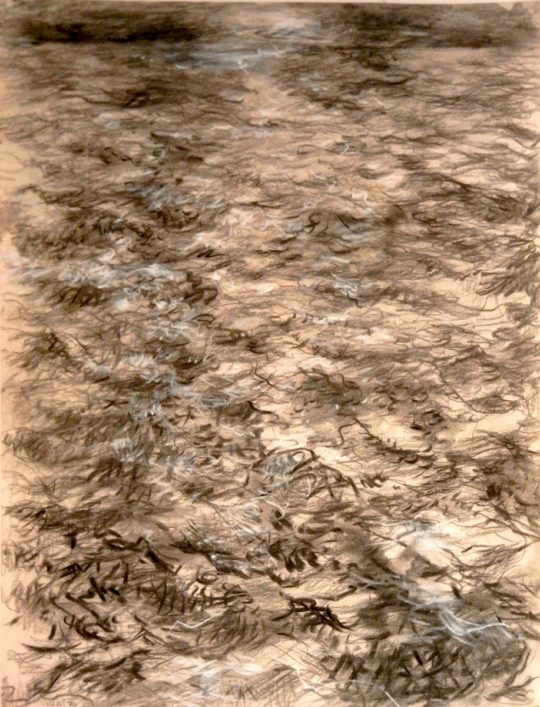

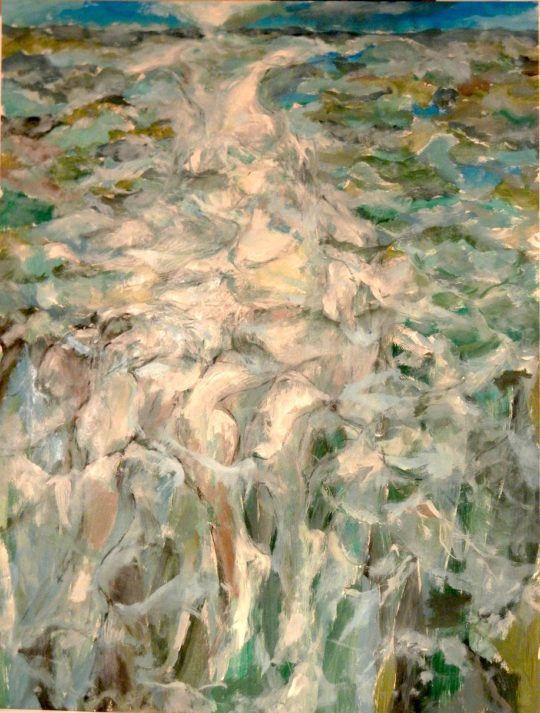

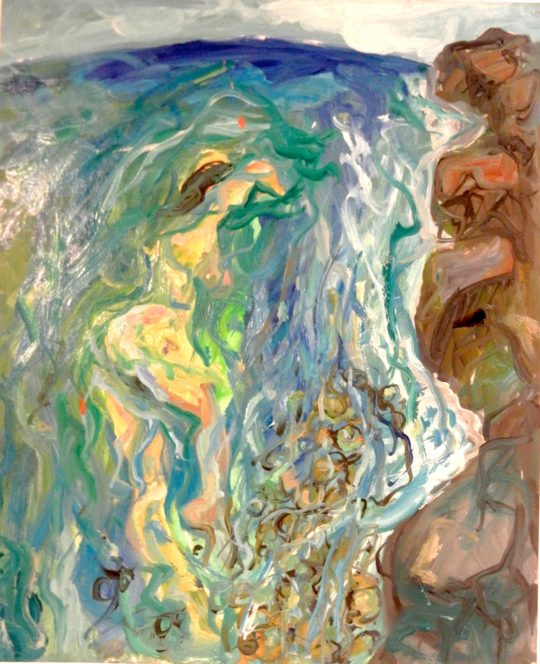

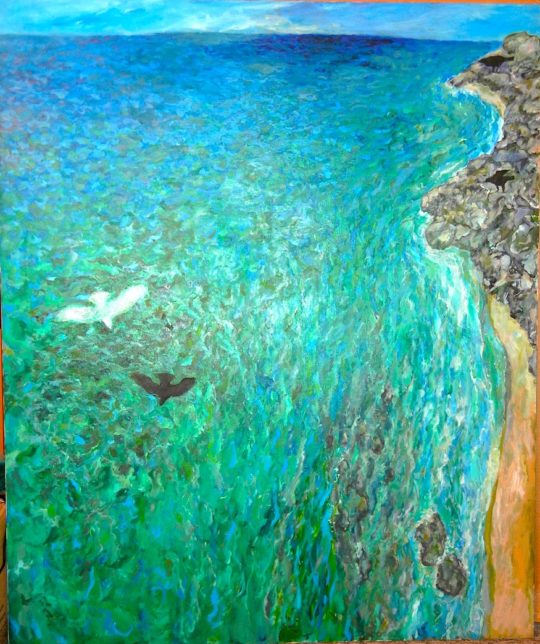

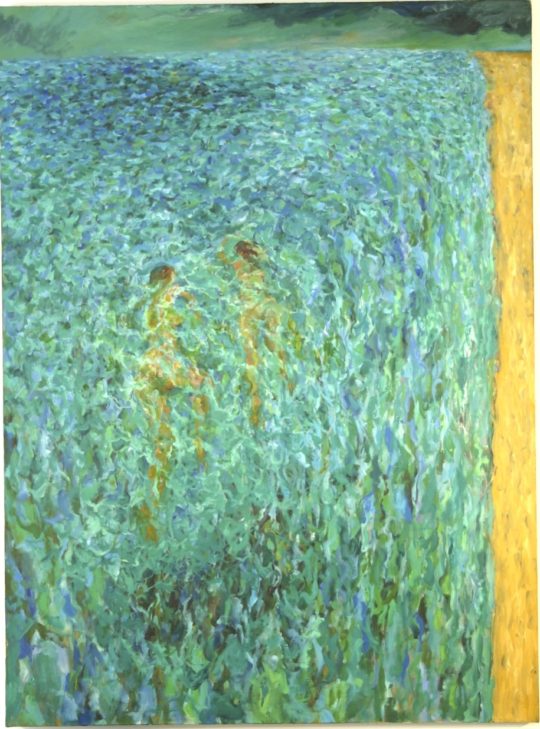

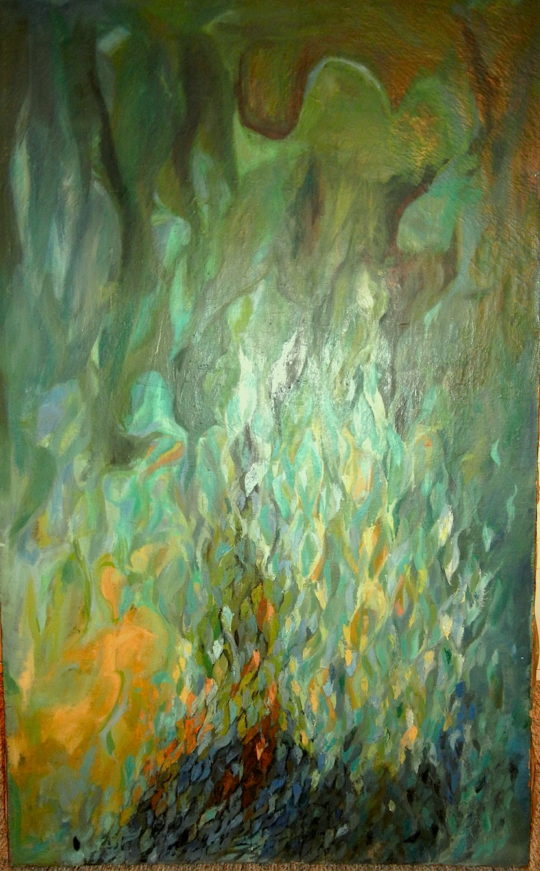

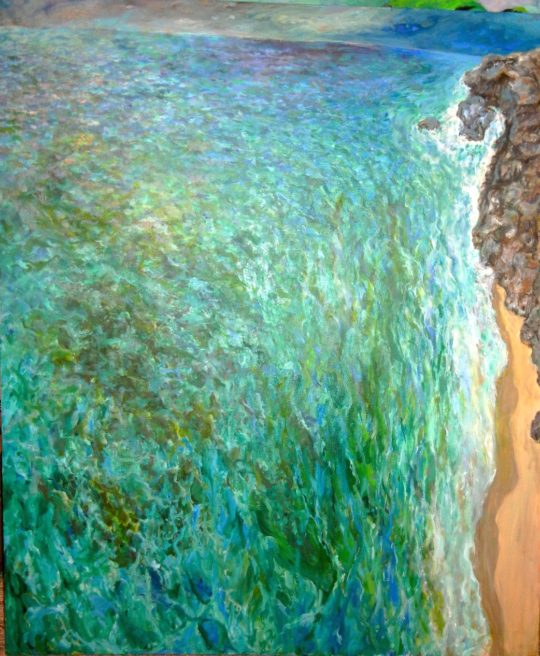

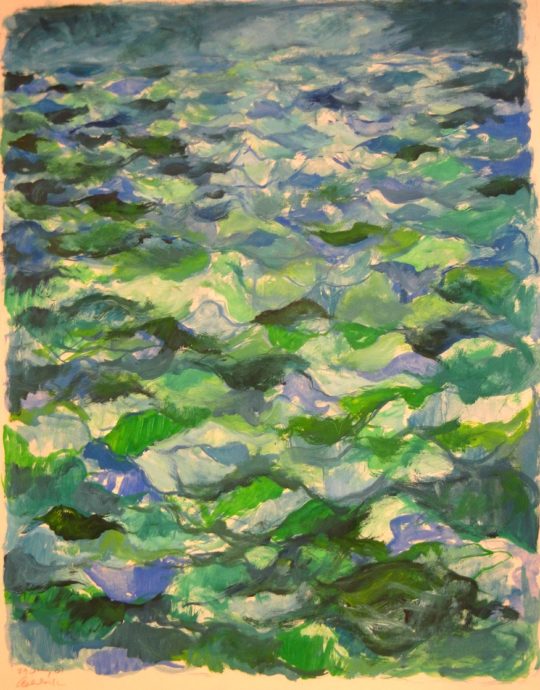

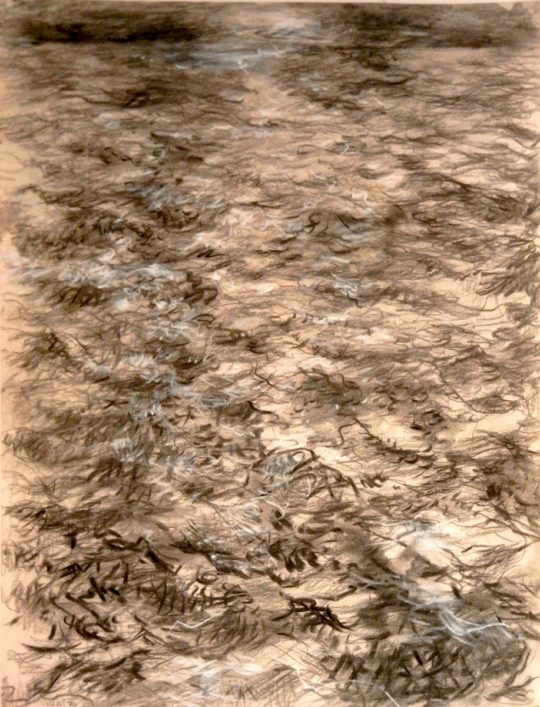

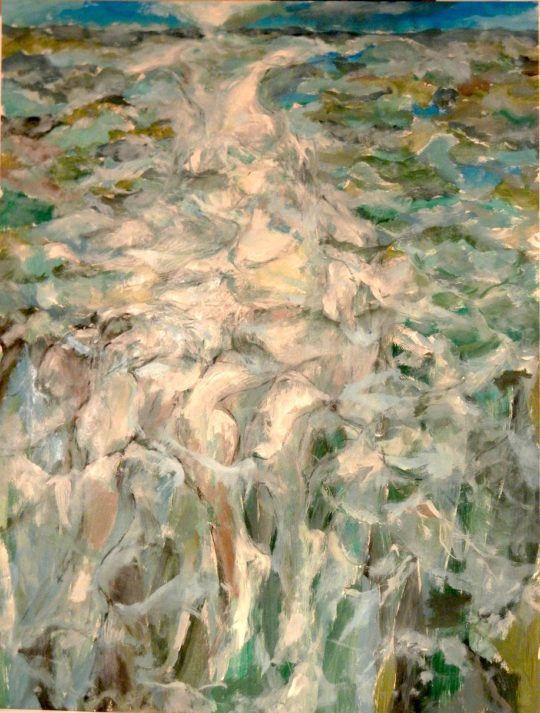

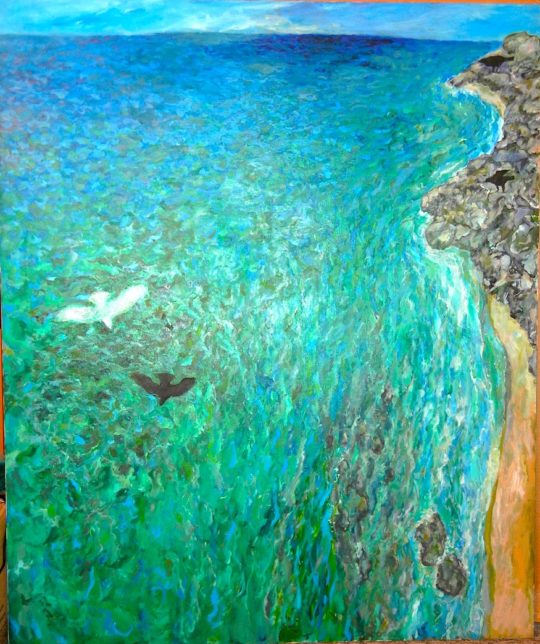

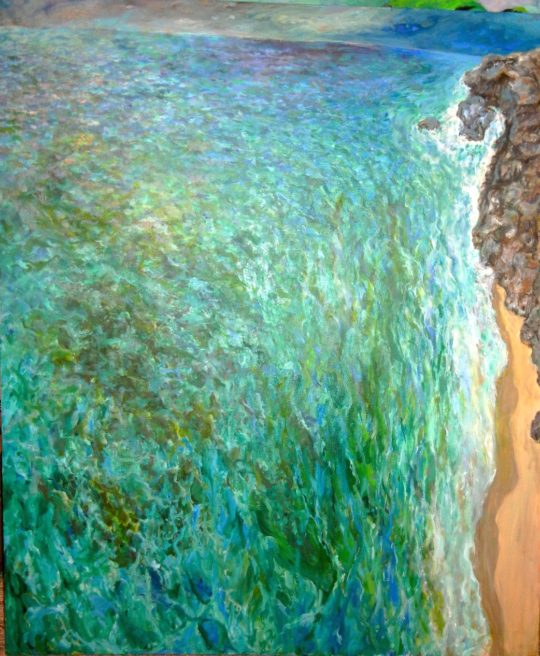

In Ashlock’s large seascapes of this same period one also feels a powerful sense of the dramatic. At first glance the viewer is faced with what appears to be a minimalist seascape of vast ocean and high horizon line. However, the eye naturally following the water suddenly plunges off the edge of the earth. We are alarmed to discover that the earth is flat! We are thrust back to the 12th century. Here is a time warp. The nexus of two worlds and two horizons are fighting for supremacy while twisting both perspective and spatial depth. This is an extraordinary series that finally reconciles pure abstraction, color field painting, calligraphic brush strokes of heavy impasto, and a recognizable subject — all into one picture plane. In fact, this series puts painting on its ear. Ashlock commented wryly that it was a matter of assuming “the perspective of several seagulls.”

For Ashlock, painting was above all about process: a process in which emotional, intellectual and physical depth was at play. In the two series discussed above, the nudes and the seascapes, it is clearly Ashlock’s desire to create the sense of motion, reinforced by color, that connects the two subjects. “At what point do you see the connections? . . . the image you want? The temptation is to continue the process, continue playing. The sense, however, is that it is important to keep putting on paint, that with the accretion of layers there is physically and emotionally greater depth.”

Ashlock remained invisible during his nearly twenty-five years in New York, living what he called “a lifestyle of extreme independence to” its fullest. Then, in 1980, he returned to the West Coast. He spent a few years in Spokane, Washington, where he continued the occasional portraits he had worked on over the years. Previously, he had painted from magazine photos – T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, P.G. Wodehouse, W.H. Auden, who also lived on St. Mark’s Place, and whose lined face would sometimes appear in the Second Avenue tobacco shop they both frequented. He also painted Beckett, whose integrity he deeply respected. “I admired him the most,” Ashlock said, “because he turned down the Nobel Prize and then gave a speech to the press about how he felt that it was inappropriate to give prizes to works of art.” In Spokane, however, the portraits turned into a series of “imaginary friends.” Interestingly, some of the faces had more than a hint of self-portrait about them, as if he was beginning to think of himself more benignly.

After Spokane, Ashlock re-established himself in San Francisco, where he studied Chinese for several years, finally pursuing more fully his lifelong interest in the ‘visual word’. By this time, however, his former abuse of alcohol and cigarettes had begun to take its toll. His health deteriorated. Gradually, the artist found himself dependent upon others for his survival. During the 1990’s he was hospitalized for a variety of problems, ranging from heart ailments to an aneurysm. Eventually, he became bound to a wheelchair, exhausted by a kidney dialysis procedure that was required three times a week. Finally, in 1999, Rex Ashlock’s body gave in to its on-going struggle.

This is the story of a love affair with art. From his earliest years, fascinated by the tiny black-and-white reproduction of Rosa Bonheur’s “The Horse Traders,” which he found in a school-book — “I looked at it and looked at it . . . I just loved it,” Ashlock believed that the image was a gateway. What was he really seeing? And how, in all the folds of imagination, could he make perception visible? That quest — not the failed relationships; not the pain — was what was interesting. Painting the layers. Achieving cohesion. And without doubt, Ashlock’s capacity to realize his vision matured over the years in New York. He left us a series of powerful paintings, showing that whatever the personal toll, he never lost the excitement of the pursuit — these paintings tug at our senses for what “honest” paintings should be. Paintings that reveal an artist who never lost the excitement of the pursuit even though he never cared to promote his accomplishments.

In the process of rediscovering Ashlock’s painting and sculpture, we can draw a better understanding — and a fresh perspective — of the art and culture of the last half of the twentieth century. Here is art as honest as it gets. One small grain of sand, unstained.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Click here to view selections of paintings decade-by-decade at The Rex Ashlock Trust website

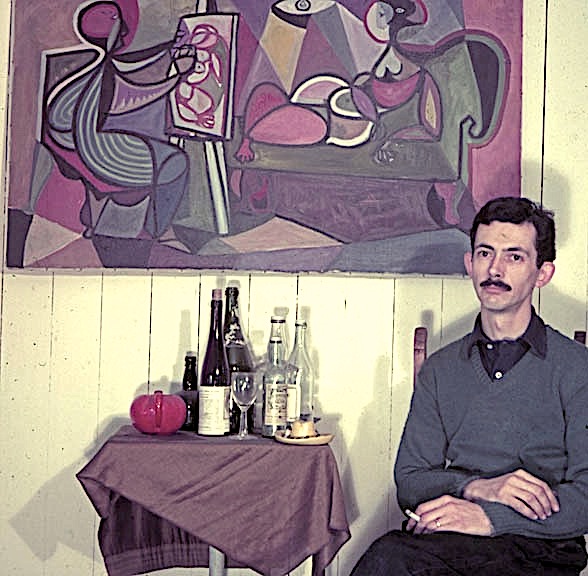

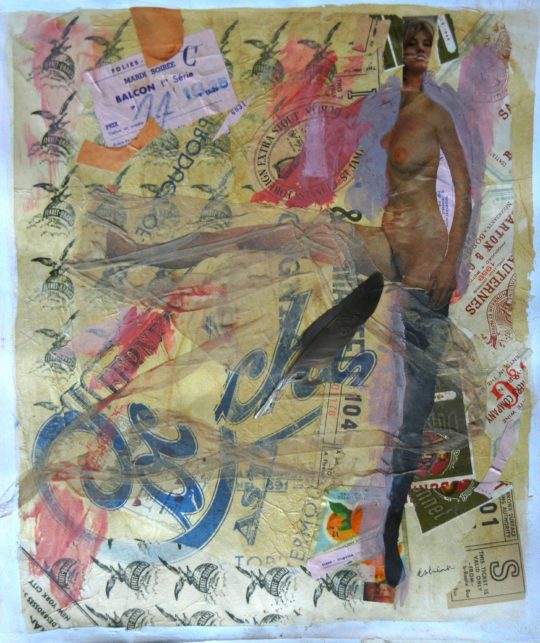

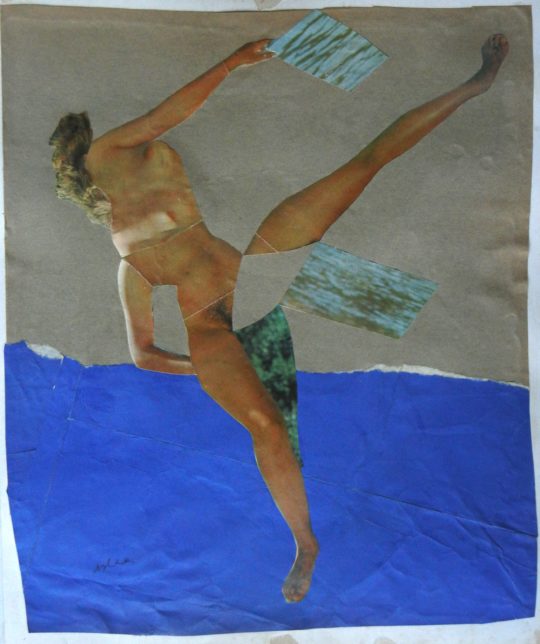

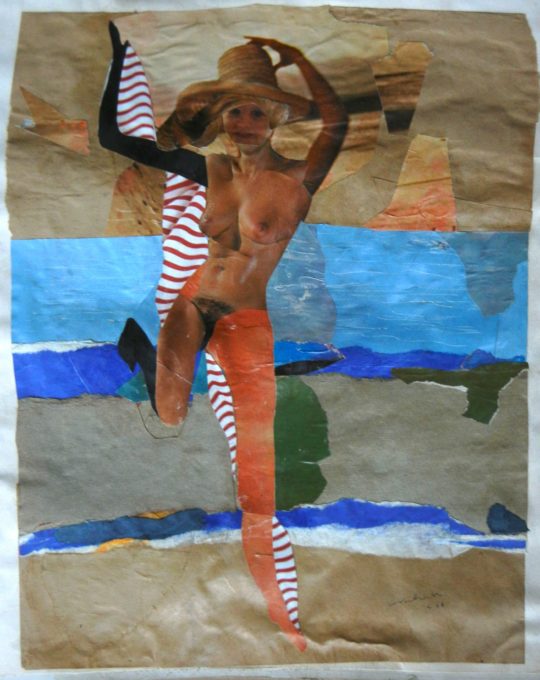

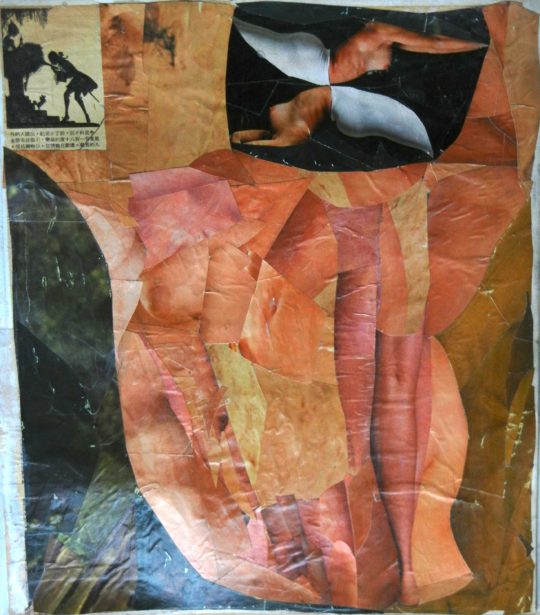

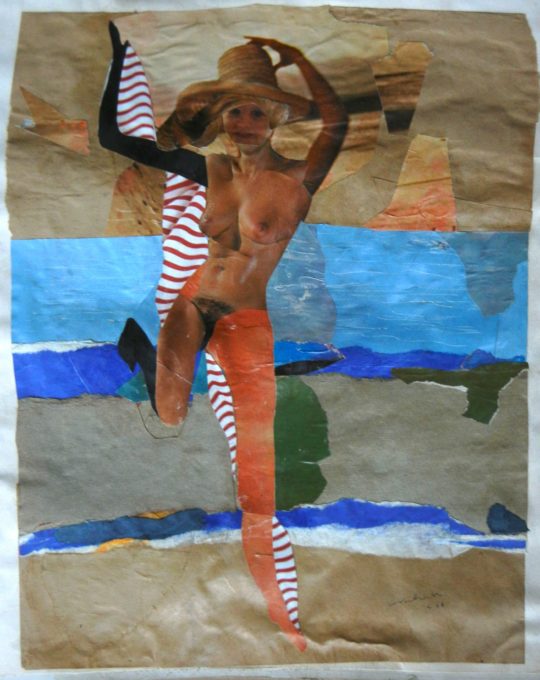

Collage: Ashlock in the 1960s

-

DETAILS

DETAILSAbolish HUAC?, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract in Gold, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract in Silver, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

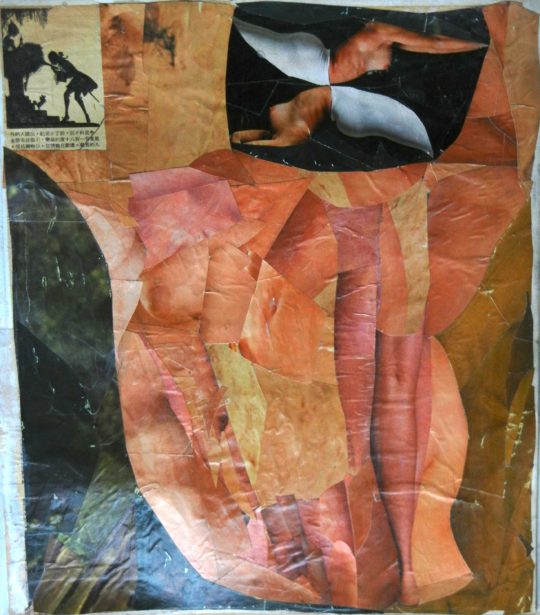

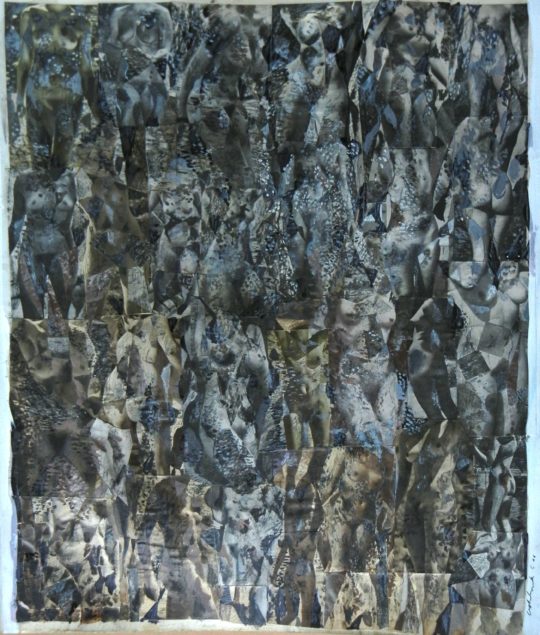

DETAILSAbstract Nude, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

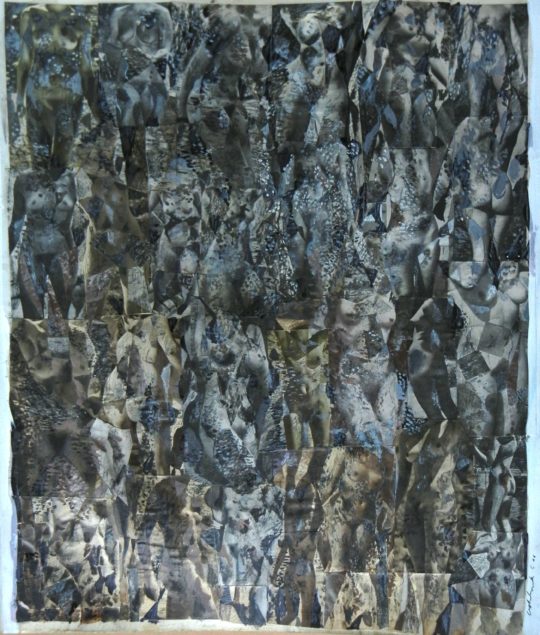

DETAILSAbstract Nudes No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCarnation Nude, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

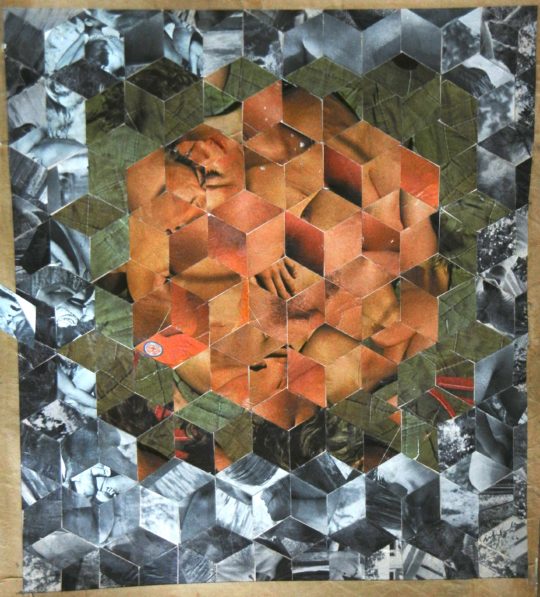

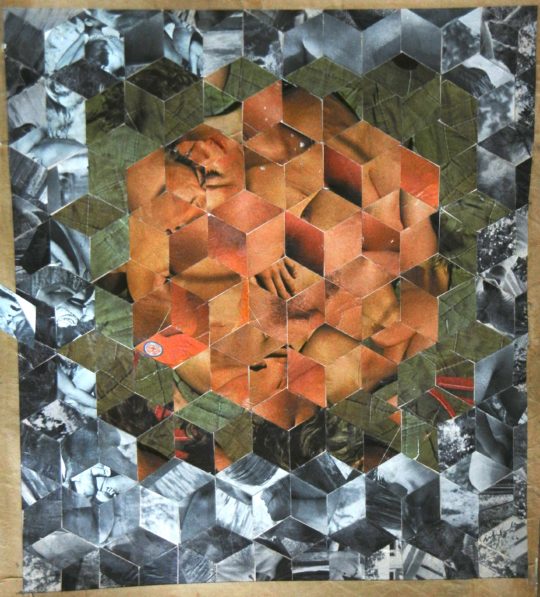

DETAILSFemale Cubed, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFemale Cubed No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFemale Nude: Eight Body Parts, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

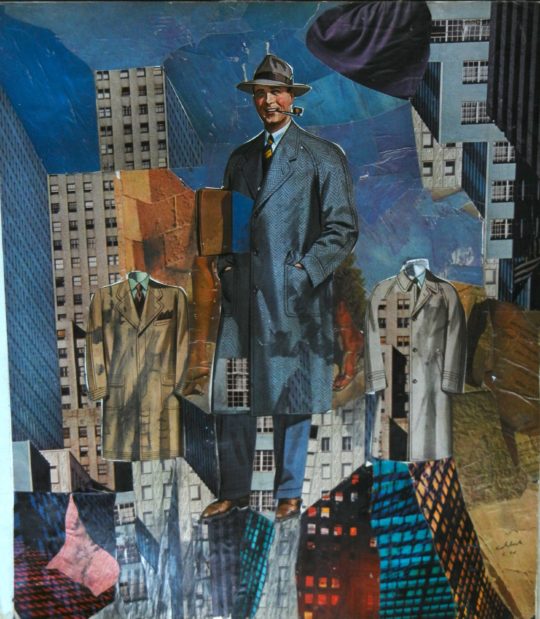

DETAILS

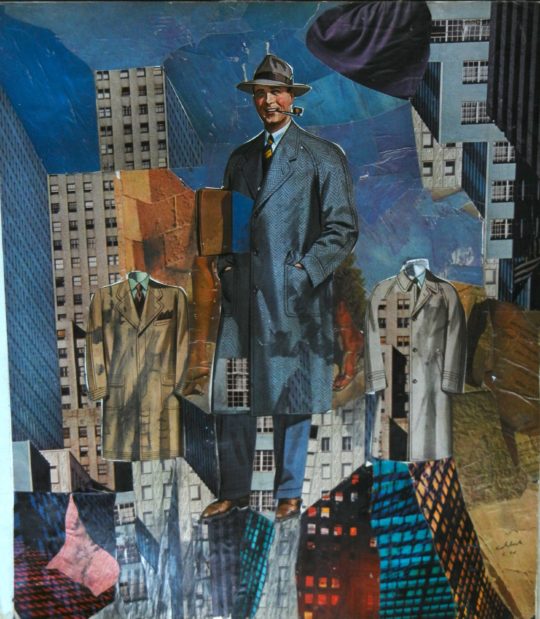

DETAILSMens’ City Fashion, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMosques and Crescents, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMovie Shoot with Nudes, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

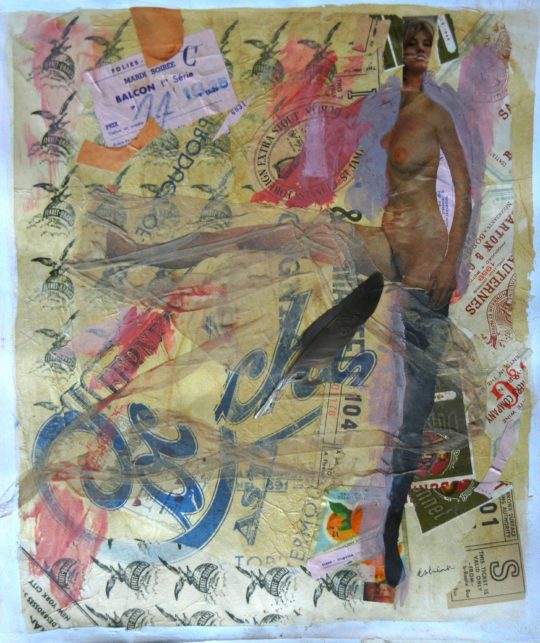

DETAILSNude at Folies, Mardi Soirée, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

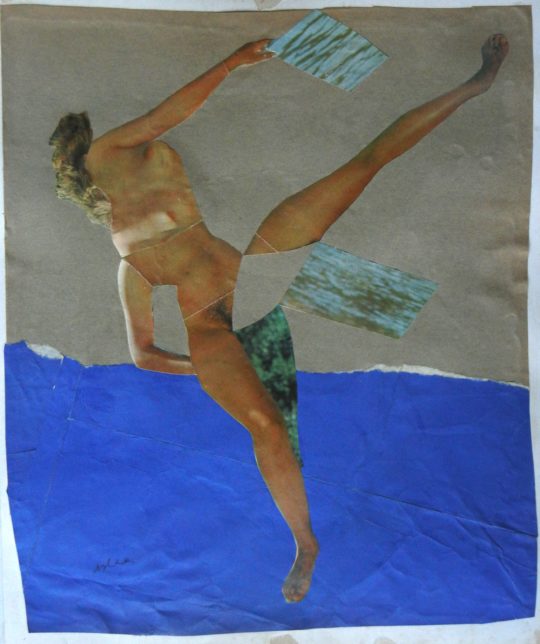

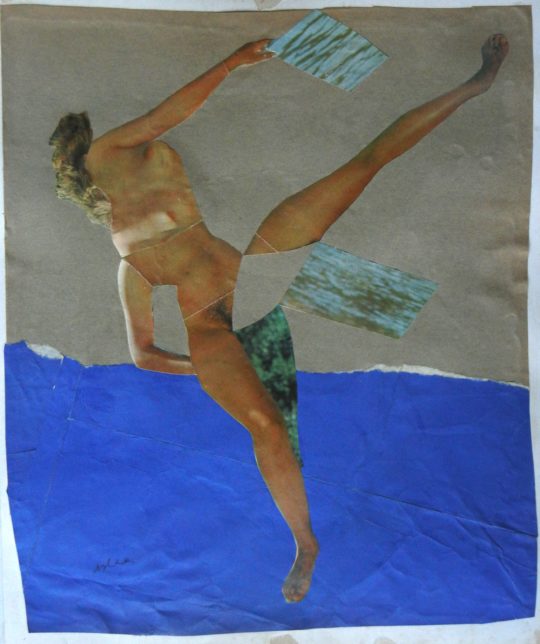

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.1, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

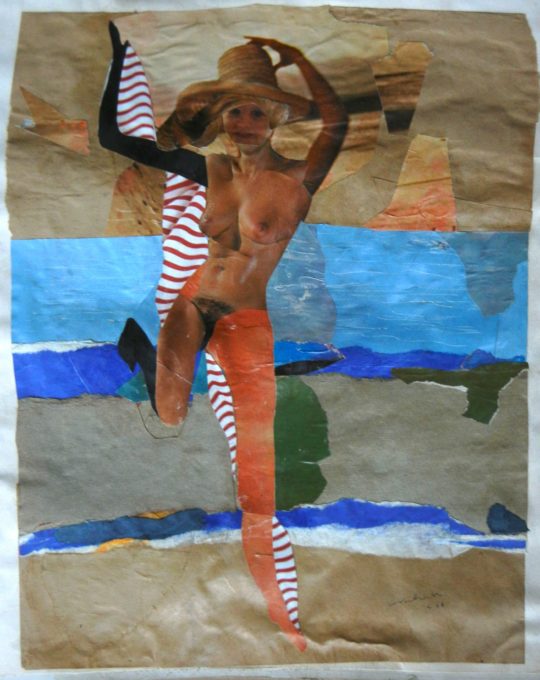

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.3, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.4, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.6, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

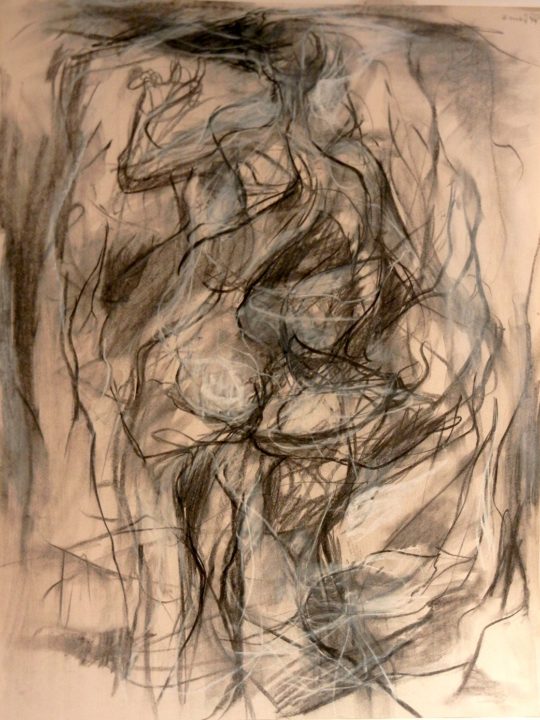

DETAILSNude Study, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.3, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.4, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.5, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

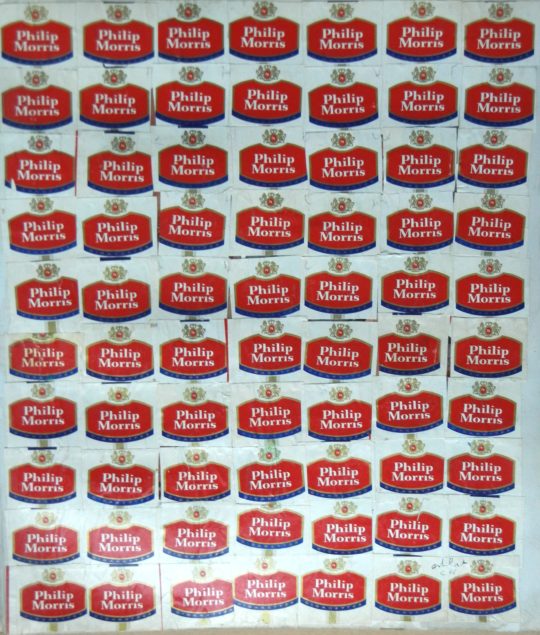

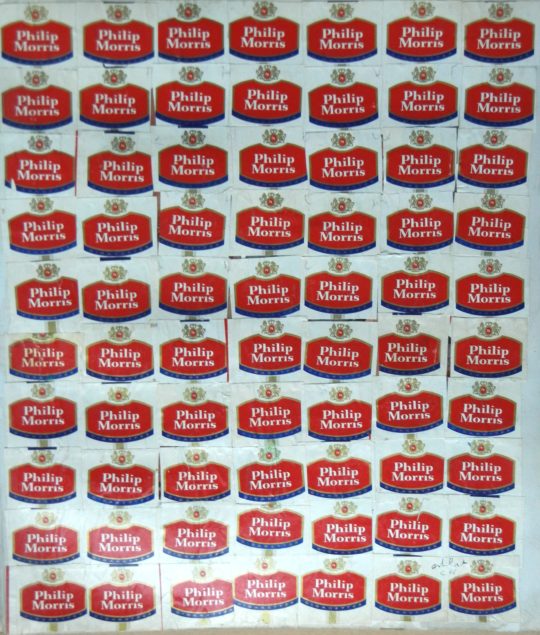

DETAILSPhilip Morris, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPlayboy Club Wants You, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScreen Star, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

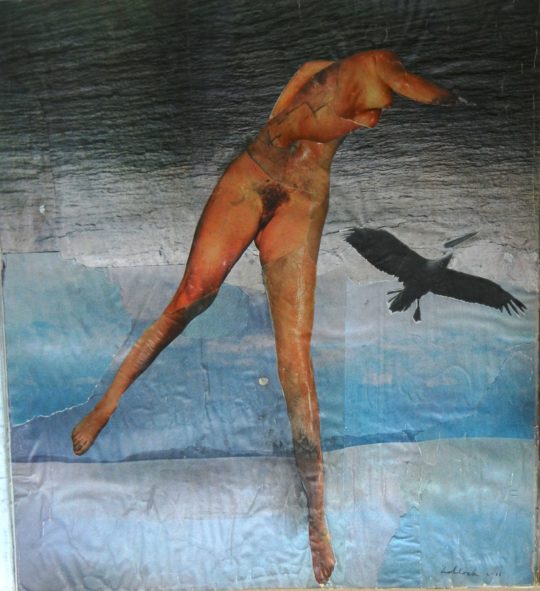

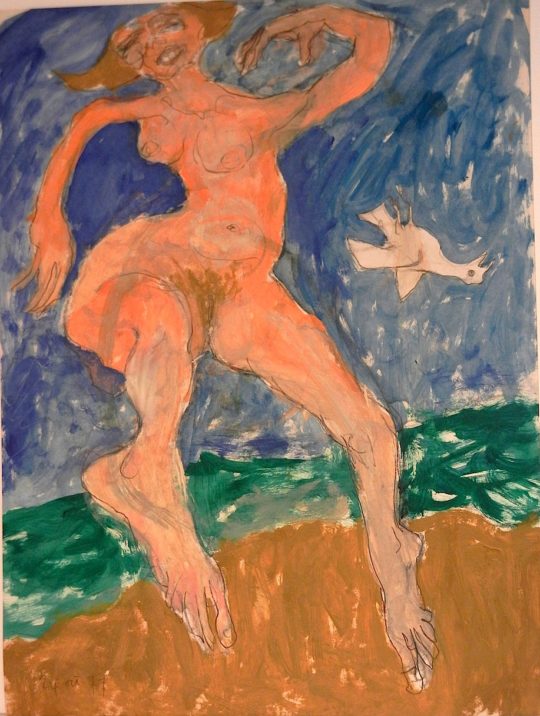

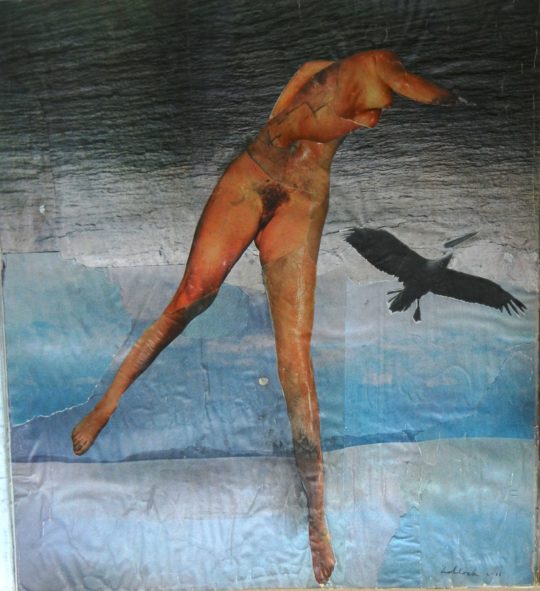

DETAILSThe Bird in the Sky, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

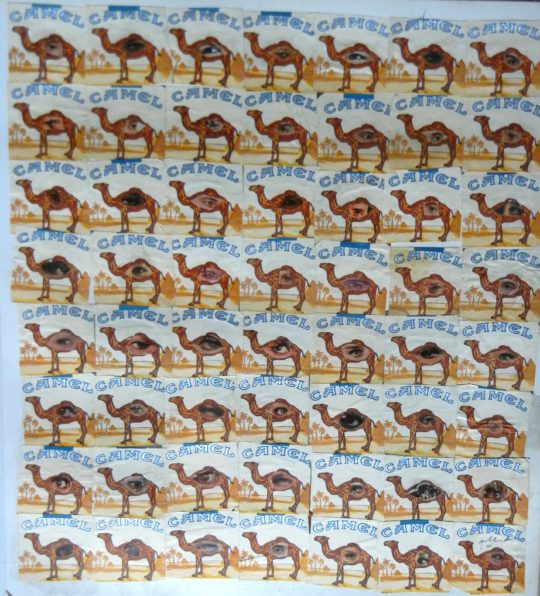

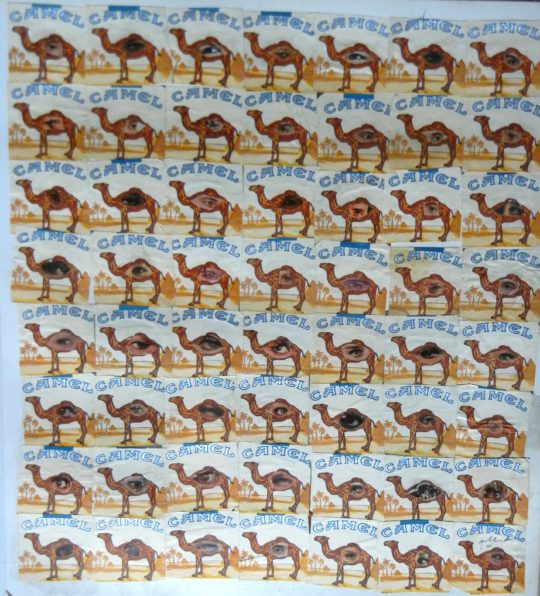

DETAILSThread a Camel Through the Eye of a Needle, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm)

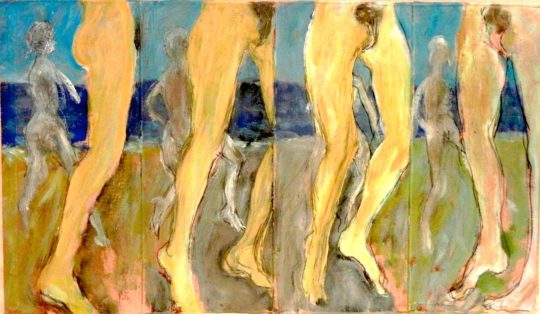

Figurative Expressionism: Swimmers, Subathers, and the Sea

-

DETAILS

DETAILSAfternoon and Twilight, 1976

40 x 60 inches (101.6 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDark Seascape, 1981

15 x 19 inches (38.1 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDark Seascape, 1978

22 x 30 inches (55.88 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.1, 1980

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.2, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.3, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.4, 1980

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLa Mèr(e), 1976

44 x 50 inches (111.76 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLarge Figure in the Sea, 1976

71 x 81 inches (180.34 x 205.74 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMirage Regatta, 1973

24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude by the Ocean, 1976

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1977

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.1, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.3, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.4, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.6, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Studies at the Beach, 1975

17 x 10 inches (43.18 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Studies at the Beach, 1975

17 x 10 inches (43.18 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Swimming, 1975

19.5 x 14 inches (49.53 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Swimming, 1975

14.5 x 17 inches (36.83 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Swimming, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSea at Night, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape, 1975

16 x 13 inches (40.64 x 33.02 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape with Pink Reflections, 1981

16 x 18.75 inches (40.64 x 47.63 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape with Reflections, 1981

15 x 19 inches (38.1 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSubather, 1977

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSunbather, 1977

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSunbather, 1959

18 x 24.5 inches (45.72 x 62.23 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSunbather, 1980

18.5 x 24 inches (46.99 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1974

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer by Rocky Shoreline, 1975

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer by Rocky Shoreline, 1975

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Birds, 1975

50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Birds of Bar Harbor, 1976

50 x 66 inches (127 x 167.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwilight & Night, 1976

40 x 50 inches (101.6 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Horizons, 1975

48 x 60 inches (121.92 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

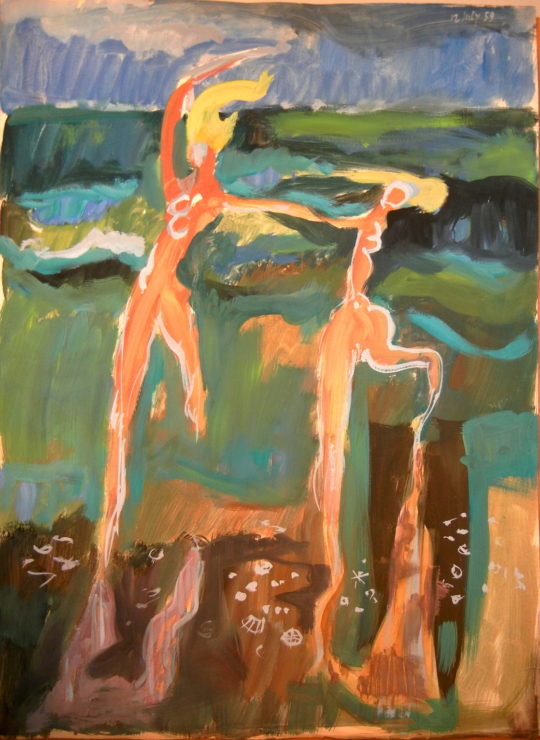

DETAILSTwo Nudes Dancing at the Beach, 1959

22 x 30 inches (55.88 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Swimmers, Double Horizon, 1975

50 x 64 inches (127 x 162.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnderwater Forms, 1957

36 x 58 inches (91.44 x 147.32 cm) -

DETAILS

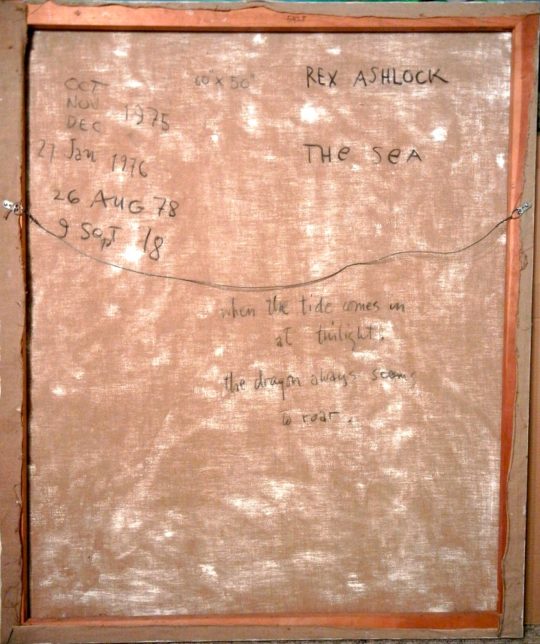

DETAILSWhen the Tide Comes in…, 1978

50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

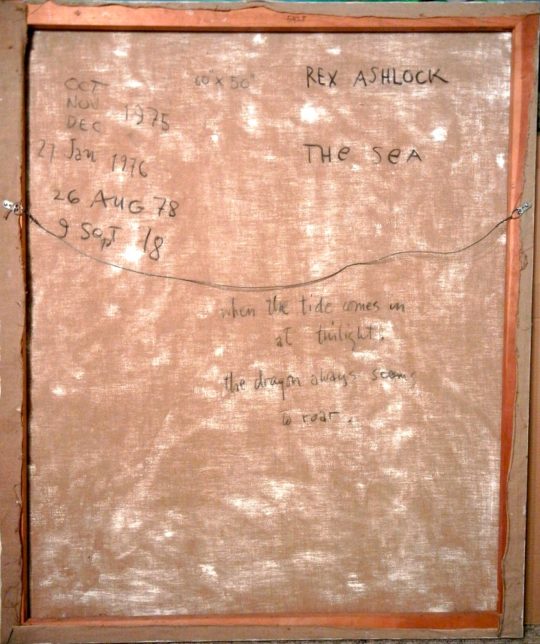

DETAILSWhen the tide comes in… (verso), 1978

50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSAbolish HUAC?, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract in Gold, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract in Silver, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract Nude, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract Nudes No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAfternoon and Twilight, 1976

40 x 60 inches (101.6 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCarnation Nude, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDark Seascape, 1978

22 x 30 inches (55.88 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDark Seascape, 1981

15 x 19 inches (38.1 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFemale Cubed, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFemale Cubed No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFemale Nude: Eight Body Parts, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.1, 1980

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.2, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.3, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure in the Sea No.4, 1980

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLa Mèr(e), 1976

44 x 50 inches (111.76 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLarge Figure in the Sea, 1976

71 x 81 inches (180.34 x 205.74 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMens’ City Fashion, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMirage Regatta, 1973

24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMosques and Crescents, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMovie Shoot with Nudes, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude at Folies, Mardi Soirée, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude by the Ocean, 1976

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1977

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on Beach, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.1, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.3, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.4, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude on the Beach No.6, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Studies at the Beach, 1975

17 x 10 inches (43.18 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Studies at the Beach, 1975

17 x 10 inches (43.18 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.2, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.3, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.4, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Study No.5, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Swimming, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Swimming, 1975

19.5 x 14 inches (49.53 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude Swimming, 1975

14.5 x 17 inches (36.83 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhilip Morris, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPlayboy Club Wants You, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScreen Star, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSea at Night, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape, 1975

16 x 13 inches (40.64 x 33.02 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape with Pink Reflections, 1981

16 x 18.75 inches (40.64 x 47.63 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape with Reflections, 1981

15 x 19 inches (38.1 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSubather, 1977

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSunbather, 1977

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSunbather, 1980

18.5 x 24 inches (46.99 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSunbather, 1959

18 x 24.5 inches (45.72 x 62.23 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1974

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer, 1979

19 x 25 inches (48.26 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer (haute relief), 1975

9.25 x 14 inches (23.5 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer (plaster on masonite), 1975

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer by Rocky Shoreline, 1975

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSwimmer by Rocky Shoreline, 1975

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Bird in the Sky, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Birds, 1975

50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Birds of Bar Harbor, 1976

50 x 66 inches (127 x 167.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Sea, 1961

40 x 50 inches (101.6 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThread a Camel Through the Eye of a Needle, 1966

14 x 16 inches (35.56 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwilight & Night, 1976

40 x 50 inches (101.6 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Horizons, 1975

48 x 60 inches (121.92 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Nudes Dancing at the Beach, 1959

22 x 30 inches (55.88 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Swimmers, Double Horizon, 1975

50 x 64 inches (127 x 162.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnderwater Forms, 1957

36 x 58 inches (91.44 x 147.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhen the Tide Comes in…, 1978

50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhen the tide comes in… (verso), 1978

50 x 60 inches (127 x 152.4 cm)

Rex Ashlock and the Sea at Carmel

Rex first came to Carmel in the late 1930s. He had grown up in Spokane, Washington and been working in Turlock, California – both inland places. The sight of the Monterey Bay – the light, subtlety of colour, texture and substance of a dancing medium which hinted at a richness of worlds below, suddenly and dramatically extended his visual awareness. He would paint the sea in every real and imaginative dimension all his life.

Early on, he set up his easel among the rocks and tide-pools near Tor Point and painted water-colors of the uneven coastline, cypresses, mists, the bay and its constant changes. Later on, in New York he expanded into oils, sea-scapes often distinguished by depths threaded with kelp-purple. In natural sequence, given his lifelong interest in the female figure, came a series of swimmers, cavorting – or teasing, almost hidden in the watery swirl. Later still, the sea, like the outer color-shell in one of his field-paintings, enclosed emerging islands, and in the 1970s it became the stuff of dream.

On a visit back to Carmel in the late 1990s Rex stood looking out at the Bay and said, This was the first sea – this was the sea I was always painting.

Margaret Ashlock Wilmot

No News found.

Exhibition Record

1945 Raymond & Raymond Gallery, San Francisco (solo)

1947 San Francisco AA (at San Fran. Museum Art. Walter watercolor prize)

1948 City of Paris Gallery, San Francisco (solo)

1949 Centennials Gallery, Berkeley (solo)

1950 Larry Blake Gallery, Berkeley (solo)

1950 San Francisco AA (at San Fran. Museum Art. Drawings prize)

1953 Contemporary Gallery, Berkeley (solo)

1953-54 de Young Museum, San Francisco

1954 L. Labaudt Gallery, San Francisco (solo)

1954 Valley Art Association, Sayre, Penn. (solo)

1954 G. Paul Bishop Gallery, Berkeley (solo)

1956-57 Duveen-Abraham Gallery, New York

1957 L’Envoi Gallery, San Francisco (solo)

1957 Phoenix Gallery, New York

1958 Bleeker Gallery, New York

1960 Brata Gallery, New York

1963 Brata Gallery, New York (solo)

1962 Bodley Gallery, New York (solo)

1962 Allan Stone Gallery, New York

1967 Avnet Gallery, Great Neck, New York

1969 Staten Island Art Association

1972-73 Princeton Art Association, New Jersey

1973 Caravan House, New York

1974 Painters & Sculptors Society of New Jersey (Honorable Mention, sculpture)

1977 Bond St. Gallery, New York

1979 Painters & Sculptors Society of New Jersey (National Arts Club, New York)

1981 Mushroom Gallery, Spokane, Wash.,

1981 Touchstone Gallery, Spokane, Wash. 1981

1983 Westside Gallery, Spokane, Wash.

- Spokane Civic Center

Other Exhibitions:

San Francisco Art Commission

Calif. Watercolor Assn, Los Angeles

Oakland Museum

Richmond Art Association, Calif.

Calif. State Fair, Sacramento.

Humboldt College

Napa College

Pacific Art Festival

Membership:

San Francisco Art Association (Artist’s Council, 1957)

Staten Island Art Association, 1969 (juror).

Work:

International House, Berkeley, Calif. (18-ft. mural)

Swedish Embassy, New York

Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC (10 drawings).

Teaching

1947-48 Calif. Sch. Arts & Crafts, Oakland

1947-56 Berkeley Evening School

1951-56 Univ. of California, Berkeley

1955-57 California School of Fine Arts

1964-65 Roslyn (NY) Adult School

1963-70 MoMA Art Center, New York

1970-73 Princeton Art Association (NJ)

1970-77 The Artists’ Workshop, New York