The Freedom of Art

— by Paul Forte

Art Frees, and in doing so, it changes us.

Art is essentially formative; it develops inwardness and independence.1

— E.E. Sleinis

After a couple of hours at an exhibition we often step out into a visual world quite different

from the one we left. We see what we did not see before and see in a new way. We have learned.2

— Nelson Goodman

The freeing potential of art and how it nurtures our independence in relation to the consciousness of others is made clear by Sleinis and implied by Goodman. Sleinis further relates his critical point about the formative nature of art to the expansion of self-consciousness and intersubjectivity, i.e., the mutual recognition of an inner life. He articulates the context within which art frees us from the habitual and routine:

Awareness of oneself as a self depends on awareness of other things and other selves.

Our subjective self only fully emerges in relation to the subjectivity of others.

Art discloses the subjectivity of others and thereby promotes expanded self-consciousness 3

Goodman’s observation about experiencing a moving exhibition illustrates how our perceptions can change, and seems in sync with Sleinis’ point about the formative nature of art and how it develops inwardness and independence. The experience of art has essentially freed us from the mundane, habitual, and routine, at least, for a time. But such freedom in and of itself is not enough. Thus, Sleinis tempers his views on artistic freedom and in doing so also suggests a link to Goodman’s insights about shared cognitive development:

Art is about freedom, but it is not merely freedom from; it is also freedom to garner rewards not otherwise attainable.

Artworks that free without furnishing rewards beyond the freeing itself must surely be judged as artistic failures. 4

For Goodman, the rewards garnered through the experience of art do not merely involve learning something new, but learning in a new way. Any concern with how art might open or free our minds is thus connected to the expansion of self-consciousness, a process that is, in turn, intimately related to cognitive growth. Furthermore, Goodman and Sleinis most likely share the belief that cognitive growth of any kind involves discovery. Discovery in the arts is not only a matter of recognizing new uses of the formal and/or conceptual means of art, discovery also seems central to learning in a new way and how this has bearing on the intersubjective power of aesthetic experience. Goodman comments on the cognitive value of aesthetic understanding and I would add, its relationship to shared aesthetic experience:

For me, cognition is not limited to language or verbal thought but employs imagination, sensation,

perception, emotion, in the complex process of aesthetic understanding.5

Goodman’s insights about the extent of human cognition in the complex process of aesthetic understanding do not explicitly take up the contentious issue of intersubjectivity. While the aesthetic understanding of individuals often differs widely, the cognitive processes underlying that understanding are something that human beings share at a fundamental level. I believe that experiencing the arts can offer the most compelling evidence for the breadth of our cognitive abilities and perhaps best reveal their universal or intersubjective dimensions. I believe that Goodman is suggesting that all human beings share basic cognitive faculties, however varied in their development given an individual’s age, mental acuity, social standing, and so forth. Inferring if not recognizing these faculties and everything else that constitutes the inner life of individuals seems essential to understanding, relating to, or even empathizing with others:

Intersubjectivity is the mutual recognition of an inner life by conscious subjects. The precondition is the conscious recognition

of one’s own inner life by a subject, as well as the assumption that other subjects share the main features of the inner constitution

which the subject identifies in itself. These include language, sensation of pain, memory capability, the drive for self-preservation,

and certain interests. Intersubjectivity is used by some authors as a substitute for an objectivity, which is regarded as unachievable.6

While it is an open question as to whether or not a shared sense of objectivity (or even relatable subjectivity), is achievable, there is broad agreement on one fact of life: We all have inner lives. Intersubjectivity is a given in so far as everyone has an inner life. However, fully relating or communicating our thoughts and/or feelings to others through art or any other means is not a given, although the inferences we make about another’s expressions, however limited or even mistaken, point to another’s inner life and can initiate a process of mutual recognition or even understanding. Awareness of oneself not only depends upon an awareness of the subjectivity of others, as one’s subjective self emerges in relation to the subjectivity of others its development can be influenced by these others and vice-versa. People who are interested in the arts might be more imaginative or perceptive, at least with respect to experiencing art, than those who are not, and if they have also sharpened their critical and/or analytical abilities, they are likely to be more fully engaged cognitively. It is possible that interest in the arts might be kindled in others through art that better reveals or encourages their imaginative or perceptive capacities, and in time, perhaps their critical abilities. The point is that we all have some capacity along these lines, whether we follow the arts or not. This capacity, however developed in the individual is the basis for our intersubjectivity. To put it the other way around, it seems safe to assume that however complex aesthetic understanding is for the individual, that individual builds this understanding on the fundamentals of cognition shared by all.

There is little doubt that the prerequisite of discovery in the arts or in any field of endeavor or even in daily life, is the freedom of an open mind. For the artist and/or thinker unconditional creative exploration and the discoveries that such exploration might lead to depend upon the cultivation of inner vision. A major problem facing the arts today is how to connect the inner vision of artists outside the purview of audiences often hungry for creative discovery. This problem is largely a socio-political and/or economic matter and the short-sightedness that accompanies the decisions of curators and others is contributing to the cultural malaise. But I do not wish to belabor this point. I will simply say that it seems imperative that freedom also be extended to the audience for art: Unconditional access to potentially rewarding art, specifically in terms of exhibition opportunities for independent artists exploring the intersubjective potential of art. It seems that the art that is often overlooked or out of favor today is work that clearly reveals the development of inwardness and independence and how this might resonate with others. How is the formative nature of art and its development of inwardness and independence related to a deeper understanding of cognition and its role in intersubjective experience and understanding? Any deeper understanding of cognition must also be accompanied by a broader understanding of this fundamentally human ability. Our individual cognitive abilities are colored by our unique experiences and yet we share core cognitive abilities with others. Our differences in terms of gender, race, and so forth, contribute to the inwardness and independence we are able to achieve as individuals, and yet however unique we might be in this regard, our achievements are always based on shared cognitive faculties seemingly unique to our species.

Today’s art market seems largely uninterested in the potential of art to enhance cognition and expand consciousness. It has no emphasis on the need to fully realize the intersubjective power of art. Formal and/or conceptual innovations in the arts may no longer be possible, leaving artistic discovery in terms of new idioms to contribute to the enhancement of our cognitive abilities, thereby expanding consciousness. Innovative works in distinctive individual styles that are provocative and cognitively engaging, are central to the freeing potential of art. This realization is at the core of a new avantgarde that has the potential to unsettle the complacency of art world insiders and their conformity to the status quo, which might explain much of the resistance to art that is both cognitively engaging and out of step with the prevailing consensus. The supporters of this revitalized art practice are often united in their belief that such art often doesn’t conform to current socio-political and/or aesthetic expectations held primarily by artists and others with vested interests in the status quo. Moreover, cognitively engaging art realized through fresh idioms is often revolutionary in its potential to deliver more than momentary diversions for a great many people, creating deeper subjective connections and mutual understanding. This is essentially the promise of creative art. The crux of the matter involves embodying creative thought and feeling in the art making process, which necessarily requires the artist and the audience paying attention to the formal dimensions and material of the artwork, with the understanding that such things are necessary but not sufficient when making or viewing a work of art. The artist thinks and feels imaginatively with images, objects, and materials, a subjective interaction that when successful elicits similar interactions in the audience. When properly recognized and understood, revolutionary or radical aesthetic practice can initiate a reevaluation in terms of art making, criticism, collecting, and curating — thus leading to a significant shift in our understanding of the place of art in our lives. Philosopher Nelson Goodman was one of the first to call for a reevaluation of the arts in relation to cognition. Goodman, writing almost forty years ago again put the issue succinctly:

The myths of the innocent eye, the insular intellect, the mindless emotion, are obsolete.

Sensation and perception and feeling and reason are all facets of cognition, and they affect and are affected by each other.

Works work when they inform vision; inform not by supplying information but by forming or re-forming or transforming vision;

vision not as confined to ocular perception but as understanding in general. 7

I believe that a new approach to art making based on this understanding and practice is well underway. Goodman’s view on how artworks work, particularly stressing that they inform not by supplying information but by reforming or transforming vision can be seen as a needed corrective addressed to conceptual art practices in the early 1970s, around the time that Goodman was writing this. Goodman was, however, primarily concerned with how we understand the various works of science and the collections in museums of, for example, cultural and natural history. He argued that the differences between the arts and sciences were misunderstood and exaggerated, that there are points of convergence in our experience and understanding of science and art. Many conceptual artists probably shared Goodman’s viewpoint, which lent credence to their work. As important as Goodman’s viewpoint about art and science is, my purpose here is to recognize the groundbreaking nature of conceptual art, that it initiated new attitudes toward art making, and to suggest a critical reason that it eventually evolved, particularly with regard to Sleinis’ view about art’s freedom to garner rewards. And yet, many in the art world have either forgotten or are unaware of Sleinis’ and Goodman’s critical insights. The insight that art offers ways of understanding the world as important as science, is founded on its intersubjective power. And it is this power that promises to free us from our isolation, connecting us with others made newly independent through shared inwardness.

In light of all this one must ask: Where are the champions of artists who realize through their art and/or writing the deep insights of thinkers like Nelson Goodman and E.E. Sleinis? In 2006 I raised a number of provocative questions that bear on the freedom of art and artists that remain relevant:

Where are the advocates of the arts who might stand behind those artists who, with no support from the art market,

continue year after year to produce art that is elegant, thoughtful, and compelling? Where are the true guardians of culture?

Where are the people who are willing and able and more than happy to lift the curtain on such art? Just where are they?

I am convinced that there is a great deal at stake here. Careers of individual artists, no matter how accomplished, are

not really the issue. Of course, and this is an opinion shared by many who really care about art, the vitality of the art world

depends upon new blood (and not just new faces), but even this pales in terms of a deeper, systemic problem.

What is ultimately at stake is nothing less than the freedom of our culture, our society. Artists who are truly independent,

artists who value art first and foremost as an expression of their uniqueness, may be the truest and boldest defenders

of something essential to our democracy. All artists who cherish freedom in America are behind the lines today.

We need the support of those on the inside who are our creative counterparts. We need people of courage and vision

who will act on their convictions.8

Many of us are still waiting for answers to these questions.

Footnotes

- E.E. Sleinis, Art and Freedom, University of Illinois Press, 2003. 6.

- Nelson Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, Harvard University Press, 1984. 85.

- E.E. Sleinis, Art and Freedom, 13.

- E.E. Sleinis, Art and Freedom, 195.

- Nelson Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, 9.

- Online Dictionary of Arguments, Philosophy Lexicon,

- Nelson Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, 180.

- Paul Forte, unpublished essay, 2006.

On Visually Poetic Art

— By Paul Forte

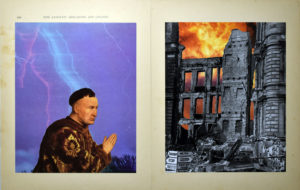

I’ve been writing poetry for almost as long as I’ve been making visual art. While this writing has perhaps had some bearing on my practice as a visual artist, the poetry or poetics of my visual work owes more to the evolution of conceptual art than to poetry per se (although, concrete poetry was a marginal influence). Before discussing conceptual art and the changes that it underwent in the 1970s, a distinction needs to be drawn between visual poetry and visually poetic artwork. This difference in light of the emergence of post-conceptual practices in the mid 1970s goes a long way toward making sense of my work as a whole. The impetus of much post-conceptual art involved what might be called a “cognitivist turn,” where the cognitive processes of knowing and understanding through art provided the basis for an aesthetic renewal. This renewal, inflected with conceptual concerns, would drive much of the art of the 1970s. Visual poets and artists making poetic objects during this period were consciously or otherwise under the sway of this aesthetic renewal. While the practices of many visually poetic artists and visual poets might be formally related, there is a fundamental difference between the two. What essentially distinguishes visual poetry from visually poetic artwork is that the former is fundamentally abstract in the way that all language is, whereas the latter is usually made from concrete, physical objects. Regardless of how imaginative each kind of work is, the experiential parameters of the poetic artwork seem broader and have an immediacy unmatched by visual poetry, however syntactically or typographically novel such work might be. Even visual poetry that discards syntax, distorts typography, or otherwise transforms the poem into a visual (or graphic) work, nevertheless still broadly functions in either a “linguistic” or semiotic way: It is a work meant to be viewed/read on a page or other two-dimensional surface. Visually poetic artworks, including two-dimensional collages and the like, on the other hand, are not limited in this way and realize a poetics in spatial and/or tactile terms through the material and form of the artwork. While the visual poem and the visually poetic artwork are both designed primarily to be seen, the latter has a pronounced material immediacy, and if words or text are also used as part of the work, they are in support of that immediacy and a visually evocative meaning or intent conveyed through the material. Written words and/or text are inherently visual and thus might also be manipulated typographically to suggest an image in addition to their semantic function, if there is one, concrete poetry being a good example of this. Consequently, there is a connection between visual poetry and visually poetic art. It should also be noted that when the language structure of some word and/or text-like work is minimal or presented as a trace or a fragment, such artworks might be considered “visually poetic” as opposed to visual poetry per se, although, given its invocation of language such work is necessarily conceptual.

An interesting relationship between visual poetry and visually poetic artwork can be extrapolated from remarks by literary scholar Willard Bohn about visual poetry. Bohn comments on how words and/or text are usually experienced and the significance of visual poetry in making us aware of the material dimensions of language: “The problem with words on the page, as with realistic artworks, is that the reader/viewer tends to look right through them. In the rush to grasp a poem’s meaning or to view the scene depicted in a painting, no attention is paid to the composition itself, which is treated as if it were transparent. Above all, therefore, visual poetry strives to motivate (or remotivate) the signifier, to restore its fundamental identity as a material object.” 1 Artworks that use images and/or objects for essentially allusive or poetic purposes, unlike much visual poetry, press the viewer/reader to see the image or object beyond its usual or accepted meaning or function. Seeing or experiencing visual poetry then seems inversely related to the viewing or experiencing of a visually poetic image or object. The visually poetic artwork is often based on found images and/or objects, the accepted meanings (and sometimes, functions) of which are preserved while at the same time offering the possibility of new meaning through novel juxtapositions and recontextualizations, combinations and changes meant to be viewed/read for their evocative poetic quality. Of course, some works of visual poetry might use, for example, collage or assemblage techniques, but the focus of these poems, however typographically striking, are usually based on the semantics of words, texts, and/or signs, as opposed to pictorial images or recognizable objects per se. Again, a visually poetic artwork might also use words and/or text, but its focus is always on the juxtaposed and recontextualized image and/or object, which is the ultimate bearer of the artist’s meaning or intent.

The visually poetic artwork or poetic object brings to mind the visual poetics of surrealism and its closely related idiom, magic realism. While the historical connections between surrealism (and magic realism) and conceptual art are tenuous at best, there are glimmers in the historical record of an underlying relationship. Marcel Duchamp’s groundbreaking readymades are a case in point, as are Rene Magritte’s word/image experiments. Arguably surreal or uncanny by virtue of their being everyday objects presented as art, Duchamp’s works not only force the viewer/reader to question the nature of art and the role of the artist, they also reveal the possibility of an inherently poetic quality in ordinary things. Duchamp’s ready-mades, long celebrated for their implicit disparagement of aesthetic values, nevertheless ultimately raised the stakes for the “aesthetic” appreciation of art through the juxtaposition of common things, particularly with his assisted readymades, in ways that enable the viewer/reader to value them for their poetic allusions, allusions often accompanied by inscriptions. According to poet Craig Dworkin this suggests that “the readymades were not just everyday objects nominated as art,” as they were often accompanied by inscriptions, and thus in his words these works embodied “a poetic/linguistic aspect from the start.” (Email, February 6, 2023) I prefer the term “designated” instead of “nominated.” The former seems a better description of Duchamp’s intention because it’s not certain that he was seeking a formal acknowledgement of his readymades as art, but Dworkin’s point is well taken. The more important question raised here is that while the act of designation as art must necessarily involve language in some sense, whether in the form of titles, artist statements, or curatorial commentary, can some designated works nevertheless be read for their allusions without the benefit of language? The issue as to whether images and/or objects can be read for connotations, poetic or otherwise, without linguistic direction or paraphrase is not fully resolved. The resolution in favor of visual meaning or intelligibility depends upon the nature of the images and/or objects employed by the artist, and particularly how well the artist has manipulated these things. Images and/or objects that are made to embody recognizable visual meaning based on shared cultural stock will more likely make sense to an audience without appealing to any linguistic input. The addition of supplemental language in terms of titles, commentaries, and so forth, accompanying artworks with culturally recognizable visual meaning, are nevertheless often useful in relating the finer details of said visual meaning. If considered for their poetic allusions, Duchamp’s readymades cannot be confined entirely to “anti-art” or relegated to the Dada camp. With time, if nothing else, this provocative work has acquired a poetic patina and become much more than a slap at bourgeois values. The readymade now seems to some as a conceptual act that also pointed toward a poetic impulse that later came to guide much surrealist art. This possibility is suggested by Dawn Ades when she observes that, “Marcel Duchamp’s readymade lit the fuse for the explosion of the object, as he took a mass-produced object out of context and gave it ‘a new thought.’ With the assisted readymade, Duchamp further explored ideas opened up by object and material. In ‘Why Not Sneeze, Rrose Selavy,’ for example, he placed marble cut to resemble sugar lumps in a birdcage, the visual deception revealed when one attempts to pick up the object.”2 (emphasis added) This work, among other assisted readymades, I contend can be regarded as a visually poetic artwork.

I cannot overlook the surreal or magic realist cast of much of my own art, due primarily to the work of Duchamp and Rene Magritte (and to some extent, Man Ray, and Max Ernst). However, early on my work was inspired by conceptual art, and I appreciated Duchamp as the prototypical conceptualist. Conceptual art as I understood and came to practice it was idea-oriented art that might use images and/or objects, found or otherwise, in poetic ways. Given this viewpoint, artwork such as mine can be considered an offspring or evolutionary form of conceptual art: A post-conceptual or cognitivist art that returned sensory experience and a sense of the poetic to the propagation of ideas. Assuming that the poetic nature of Duchamp’s readymades planted a seed that eventually blossomed into some forms of surrealism as well as conceptual and eventually post-conceptual art, it might be argued that the more stringent or analytical forms of conceptualism (exemplified by the work of Joseph Kosuth, and others) that developed in the late 1960s were an aberration. The attempt to reduce art making to philosophical discourse in the barest terms eventually hit a brick wall. This putative reductive turn failed to fully eliminate the aesthetic concerns of many artists, concerns often subsumed under the methods, techniques, and materials used to produce and exhibit even the primary vehicles of conceptual art, for example, text and photographs. Moreover, as it turns out reducing or attempting to reduce art to analytical propositions (which ironically were often poetically inflected) is not the only way to make art with a philosophical bearing, or to posit an inherently “conceptual” basis for all art if those are the artist’s intentions. Artmaking might take on a philosophical bearing in an older and more fundamental way. Pre-Socratic philosophy, philosophy prior to its reduction to metaphysics integrated poetic thought with reflection on existential questions and the meaning of life in ways that seemed to respond more fully to human experience. Now, a “poetics of conceptual art” might seem a contradiction in terms, but only from a strictly analytical perspective or approach to conceptual artmaking. A number of contemporary poetic conceptualists or conceptually oriented poets come to mind: The colorful language experiments of Lawrence Weiner, the emblematic works of Ian Hamilton Finlay, the poem objects of Dieter Rot, and the word pictures of Ed Ruscha, among others. And, of course, many artists involved with conceptual art were also practicing poets, artists like Vito Acconci and Carl Andre. Even one of the founders of conceptual art, Sol Lewitt, made work that while perhaps never intended to be appreciated poetically, seems in some respects intuitively so. And how can we forget that Marcel Duchamp was influenced by the poets Apollinaire and Mallarme. It appears that there has always been a poetic strain in at least some conceptual art, and in many cases the poetry inherent in it seemed to enhance the very ideas the work was intended to deliver.

The work of philosopher Paul Crowther seems particularly relevant to visually poetic artwork as it relates to conceptual art. Crowther writes: “Many of the things we experience have quite specific cultural associations – which form a kind of contextual space – over and above their literal meaning or familiar function. Sometimes, indeed, we manipulate these things so that attention will be directed to the associated meanings. (This, of course, is a key stratagem of the advertising industry) Such manipulations can take various forms. For example, an object can be invested with associational meaning simply by being placed in a new context. Such investiture can also be brought about by physically modifying an object, or by juxtaposing one object with another, or by relating it to a title or text.” 3 Artwork based on the selection, juxtaposition and recontextualization of images and/or objects for the associations that they might occasion, connections with metaphorical and/or symbolic potential, seem more likely to sustain a poetic charge than art unconcerned with these things. When it comes to the poetic possibilities of images and/or objects to be used in this way the practice of the artist needs to be flexible and intuitive if the work is to have any vibrancy and offer surprises. An intuitive approach will largely avoid presenting preconceived or cliched results and better enable the viewer/reader to appreciate the work for its allusions and the ways that they are conveyed.

At this point it is helpful to return to the distinction between visual poetry and the visually poetic artwork and the inverse of Bohn’s observation about the restoration of the fundamental identity of the signifier in a visual poem (as a material object); the inversion being where the material of an artwork that has been juxtaposed and recontextualized might acquire allusive or metaphorical qualities in addition to the commonplace identities of these things. The notion of visual poetry has its roots in one interpretation of Ut pictura poesis (“as is painting so is poetry”), a belief that would eventually inspire, among other things, what came to be known as “emblematic poetry” in the 16th century. The sensibility informing this kind of visual poetry and shaped verse from about the same period seems to stretch back through the ages, both forms of poetry being precursors of things to come. Might Ut pictura poesis be completed by a modern sensibility bringing it full circle? Thus, “as is painting so is poetry,” but also: “as is poetry so is painting.” The fact that the inverted formulation is a tautology – that it says nothing about painting and poetry as such – might nullify my argument about the manipulation of found objects by the artist to suggest metaphorical associations, were it not for the evidence of the artwork itself. In this case, a bit of circular nonsense acquires a shimmer of meaning by virtue of experiential truth. Concrete poetry is a descendant of emblematic poetry, and this modern form of visual poetry to some extent influenced some art made after world war two. But by the early 1970s it was an intuitive sense that conceptual art was evolving that had the greatest impact on the artmaking of those artists still concerned with conceptual issues. The notion of found objects imparting meaning can be traced to the readymades, which may have contributed something important to the idea of poetic objects. Conceptual art evolved primarily through a fundamental reorientation toward ideas; that ideas might be grasped or enhanced through the senses and an understanding that the poetic presentation of ideas might also contribute significantly to understanding them. The foregrounding of ideas is the hallmark of all conceptual art, a practice presumably founded on a priori thought, where the dependence upon sensory experience in artmaking is reduced to a bare minimum. Here the analytical (or logocentric) exercise of the mind is considered the primary means and ultimately reason for making art. Ultimately this approach to conceptual art seemed to bring a fundamental question into stark relief: How is thinking manifested through art and taken up by the senses? We obviously can think in other than just linguistic, mathematical, or broadly speaking, discursive terms. So, while conceptual art was right to emphasize ideation in the making of art, thereby shifting the focus away from what was a moribund formalism that had run its course, in its most rigorous incarnations this radically new attitude seemed to downplay or deny the importance or even the possibility of sensory knowing or understanding through art. Conceptual art that embraced a strictly analytical approach thus became its Achilles heel. How this transpired first requires a good working description of the paradigm shift called “conceptual art.”

One such description of Conceptual art that has breadth and clarity is proposed by British philosopher, Matthew Kieran in his book, Revealing Art. Kieran writes: “What makes the artistic lineage of conceptual art into a coherent story is the concern with ready-made or mundane objects, the primacy of ideas, the foregrounding of language, the use of non-conventional artistic media, reflexivity and the rejection of traditional conceptions of sensory aesthetic experience.” 4 These concerns are widely recognized aspects of conceptual art, although, “the primacy of ideas,” is an inherent characteristic of all conceptually oriented art and not just one concern among others. My own work over the years has employed mundane objects, and has at times foregrounded language, used non-conventional media, and explored reflexivity. It has not, however, wholly rejected “traditional conceptions of sensory aesthetic experience.” Kieran goes on to make a comment that seems particularly relevant to the development of my work in relation to post-conceptual art: “Ironically enough, some pieces which are in part conceptual also involve sensory aesthetic appreciation [emphasis added]. They may not conform to traditional notions of beauty, or may involve materials we are not used to approaching in aesthetic terms, but there is no denying that sometimes they yield aesthetic rewards.” 5

The question arises as to whether art that is partly (or broadly) conceptual by virtue of yielding some measure of aesthetic sensory appreciation is a result of the evolution of conceptual art or a reaction to its more stringent forms. Conceptual art in its most reductive and rigorous forms essentially held that objects and/or materials were contingent elements and not the point of the art. This was the basis for a so-called “dematerialized” approach to art making. However, we have come to believe that ideas in art are inseparable from some measure of sensory experience and moreover that the power of an idea often depends in part on how aesthetically rewarding the work is. An aesthetic image or object is valuable not simply because of the pleasure it affords, rather its value resides in the way it embodies an idea or ideas, a quality that is more likely to sustain the attention or engagement of the art viewer/reader. This is the essence of the relationship between the aesthetic and the cognitive,6 which involves the sensory apprehension of ideas. The sensory quality of an artwork can have significant conceptual bearing on an artwork and therefore be inseparable from the idea that informs it. Embodied ideas are more successful when they carry an aesthetic and/or poetic charge: They inspire and move us and perhaps most importantly, often generate new ideas. A cognitivist or “sensory-based conceptual art,” is not only potentially poetic way of making art through a variety of media, it can also make an important contribution to enhancing cognition itself. The evocative appearance of the artwork, in whatever form, is often an integral part of the idea that it embodies. The conclusion then is that a cognitivist orientation was bound to surface and drive the evolution of conceptual art toward a post-conceptual phase or condition of art making.

It is not surprising that the impact of conceptual art isn’t particularly evident in the work of many contemporary artists, especially those influenced by conceptual art

who went on to make art utilizing traditional media, techniques, and so forth. Yet, conceptual art laid the groundwork, or had an implicit effect on the artistic practice of many contemporary artists, and even implicitly informs the work of those born after the heyday of conceptual art. Conceptual art of the early to mid 1960s instilled an attitude that eventually blossomed into often poetic forms of essentially cognitivist art. With Kieran’s description in mind, it’s perhaps ironic that the original conceptual approach to art making led to art based upon the sensory apprehension of ideas. On the other hand, maybe conceptual art was always divided between the “purists,” those who would reduce the art experience to proposing ideas through “non-aesthetic” uses of text and/or photographs versus those who embraced sensory or broadly non-propositional modes as a necessary or inevitable aspect of all art, including much art with a conceptual orientation. The foregrounding of ideas remains a guiding principle in the artmaking of many contemporary artists, although many artists today have rejected strictly reductive approaches and accept the premise that sensory experience is important if not essential to the dissemination of ideas through art, a premise that would have been alien to many analytical conceptualists of the 1960s. A cognitivist approach to the making of art is the result of, or inspired an early awareness of the diverse manifestations and intermedia experiments of artforms moving away from the edicts of a reductive and “dematerialized” conceptual art. Cognitivist or post-conceptual forms of art, while overshadowed by the reemergence of more traditional artforms like painting and sculpture in the 1970s and 1980s, nevertheless continued a tradition of experimentation in the arts and quietly made important inroads in our understanding of the relationship between thinking and seeing, the cognitive and the aesthetic, and words and images or objects.

By the mid 1970s, conceptual art had largely shed its austere beginnings, giving way to a plethora of art forms and revitalized traditional techniques, many of which nevertheless remained idea oriented. It seemed that conceptual art had indeed changed. Sensory modes of experience came to the fore as artists also began to look at traditional media in a new light. Consequently, “idea art” in its initial reductive and “dematerialized” phase held sway from around the mid to late 1960s and by the early 1970s had largely lost its hold on the imaginations of many artists. For those of us who were working in the 1970s and rode the tail end of the paradigmatic conceptual shift (and the emergence of post-conceptualism), the historical description of conceptual art provided by Kieran is helpful in tracing the roots of much contemporary art. While this shift in artistic practice is common knowledge to many artists and arts professionals, a fuller discussion of its impact on the art making of those more “idiosyncratic” idea artists who emerged in the 1970s is long overdue.

Having intuited a cognitivist approach to art making in the mid 1970s, I began using found material in conjunction with traditional media, but with a new attitude. In this context, philosopher Paul Crowther again raises some interesting points regarding the nature of contemporary art, particularly from this period. According to Crowther, artwork in what he calls the “designation tradition” (works designated as art by the artist based on some theoretical standpoint, a fundamental conceptual strategy initiated by Duchamp’s ready-mades) can, in his words: “stake a claim to artistic status only insofar as they adopt the presentational formats of the nodal art practices.” 7 By nodal art practices, I believe that Crowther means primarily those culturally sanctioned practices like painting and sculpture, the presentational formats of which are then adopted for unconventional purposes. To lay claim to artistic status, however, works in the designation tradition must do more than just embrace the presentational formats of recognized art practices. By simply presenting a lackluster work in the manner of, say, a painting, will not in and of itself somehow give the work the vibrancy needed to engage people. Nevertheless, Crowther is on to something when he proposes that adopting such measures for these works leads to an interesting possibility. Namely, it’s possible to produce a work that he calls a “connotative image,” even if it is, according to Crowther, “comprised entirely of elements that were not actually made by the artist.” 8 Borrowing elements to make art, of course, has become routine with many contemporary artists. But to what end? If this practice results in art that foregoes, in Crowther’s words, “a range of specific connotational meaning that is recognizable on the basis of shared cultural stock,” 9 then the art may not have much long-term significance. And that is part of the problem. Connotative images, evocative works that for example employ metaphor and/or symbolism, seem to be one solution to the further development of a cognitivist art, an art with both conceptual and aesthetic integrity.

Beyond vexing questions about the nature of originality, merely embracing the presentational formats of recognized art practices remains a problem because appropriation of elements not made by the artist for little more than the sake of novelty or to make a theoretical point, or to advance a curatorial agenda, in my opinion, can seriously undermine an appreciation of the cognitive value of art. Such practices are essentially retrograde and echo the worst aspects of an ideologically and/or economically driven “conceptualism.” Appropriated or not, the point is to use material and media in ways that engage the mind and senses imaginatively and critically. Art that does this effectively seems to better enable the production of a connotative image. The problem is very complex because many cultural practices today are undeniably creative and sometimes virtually indistinguishable from practices considered artistic. I think some artists, particularly those with a “sociological interest” in art, either confuse these terms (creative and artistic) or take advantage of the confusion. I am not suggesting that these practices have no value to the culture, only that their full status as art is problematic. A work with a socio-political message only becomes artful when it also explores the cognitive/aesthetic nexus of media with a concomitant emphasis on the artist’s individual style. A socio-political work might creatively inform the viewer/reader about current issues without providing an aesthetic experience through an individual re-working of media, but this practice cannot be considered inherently artistic. Crowther is suggesting, and I am basically in agreement, that there is something fundamental about an aesthetic experience; something essential that art offers that other cultural practices, however creative, cannot. To support his argument about the possibility of connotative images, he offers two tests that might enable us to recognize work in the designation tradition that holds out a possibility of this experience. The tests are: “(a) a work’s having a phenomenal structure or physical presence that is engrossing in its own right, and (b) it is having a specific connotative significance (or range of such significance) that is recognizable on the basis of shared cultural stock without reference to accompanying explanatory texts.” 10

While I empathize with Crowther’s overall aims, my view regarding descriptive or explanatory texts is not as prohibitive as his position seems to be. Unfortunately, such erstwhile texts are sometimes a distraction or even counter-productive when the writing provided by an artist or a curator to accompany the art has little or nothing to do with the phenomenal properties of the work at hand and is focused primarily on the social and/or political content of the art. So, I understand Crowther’s focus on an unmediated experience up to a point. But I hesitate to downplay the use of explanatory or descriptive texts in support of art, my own or anyone else’s, provided that these texts address the making of the work and its phenomenal properties in relation to any content in clear and appropriate terms. After all, phenomenological reflection on artwork that aspires to what Crowther calls a “post-curatorial status,” whether presented as an explanatory text to introduce the artwork or appearing in a related cultural context, such as a critical review, could be valuable by adding a fresh perspective on the art that might not occur to some. Moreover, text is already implicated when titles and/or work descriptions are presented along with the art in an exhibition setting. Providing such information often enhances the experience of the art and can lead to a deeper appreciation or understanding of it.

The notion of art comprised of elements that the artist finds being capable of offering a range of connotative significance, again, “recognizable on the basis of shared cultural stock,” also points toward the solution of a problem endemic in the contemporary art world. This involves what Crowther terms “curatorial art,” art that often has little to say to an art viewing public unfamiliar with or uninterested in narrow curatorial agendas. Crowther’s point is that much of this art exists simply because of the curatorial and managerial demands of the contemporary art world and little more. Art that does not accede to these demands, but instead opens avenues for self-reflection and a greater understanding of the meaning and function of art in our lives will in the end trump curatorial art for no other reason than that it truly speaks to people. The artist can never know conclusively whether his or her art truly speaks to people. But if it inspires others to be more creative in their lives, or if the work enables them to think about something in a new way, or if it just makes them feel good about being human then it speaks to them in some fundamental way. I believe that the real value of art involves how it can contribute to the personal growth of people; how it can show a way toward a more meaningful life. Perhaps most importantly, such art also advances artistic freedom.

A post-conceptual and subsequent cognitive approach to art making is revolutionary, not just because it maintains the primacy of ideas and renews the sensory aspects involved in the making and experiencing of those ideas, but revolutionary in the sense of expanding our cognitive abilities through aesthetic experience. A cognitive approach to the making and experiencing of art sets artist and audience alike free to engage the imagination on any number of fronts. The visually poetic artwork is at the forefront of this revolutionary change. The poetry of thought or poetic thought, expressed through images and/or objects can deepen our sense of being in the world by instilling wonder. The best art being made today, inside or outside the art world, offers what the best art has always offered: New ways of knowing and understanding ourselves and the world. Whether such art does or doesn’t succeed in the art market is incidental to its larger purpose. Most artists who work at this level would probably agree with this. For serious artists, art is essentially a vitally important way of exploring what it means to be human.

– Paul Forte, 2023

Footnotes

- Willard Bohn, Modern Visual Poetry, Associated University Presses, 2001, p.16.

- Dawn Ades, “The Poetic Object,” in Surrealism Beyond Borders, editors Stephanie D’Alessandro & Matthew Gale, exhibition catalog, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022. p.270.

- Paul Crowther, The Transhistorical Image, Philosophizing Art and its History, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p.180.

- Matthew Kieran, Revealing Art. Routledge; London and New York, 2005. p.131.

- Ibid. p. 131.

- A good working definition of “cognitive” can be had from philosopher, Nelson Goodman: “Under ‘cognitive’ I include all aspects of knowing and understanding, from perceptual discrimination through pattern recognition and emotive insight to logical inference.” See Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, Harvard University Press, 1984. p.84. According to Goodman, “cognitive” and “conceptual” are not interchangeable terms. “Cognitive” is the overriding term here.

- Paul Crowther, “Cultural Exclusion, Normativity, and the Definition of Art,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Spring 2003. p. 129

- Ibid. p.129.

- Ibid. p.129.

- Ibid. p.129.

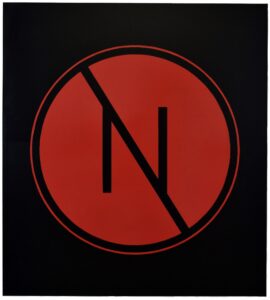

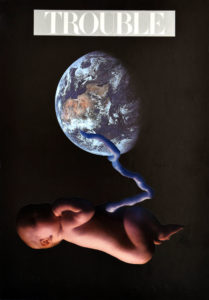

Toward A New Political Art

— by Paul Forte

Everyone is political in his or her own way — Thomas Piketty

Thousands of artworks are reviewed every day by museum directors, curators, and staff at public and private institutions. Most of the work that passes through their hands, usually in the form of digital files and other forms of representation, is nowadays often judged to be insufficiently edgy, provocative, or socially relevant, all characteristics considered to be desirable from a market standpoint. Given how closely public and private institutions that exhibit art are aligned with market forces, one might assume that art that seems to have little or no market appeal would be the primary factor in its being passed over by those mounting and promoting exhibitions. But this situation cannot be due entirely to the influence of art markets. Curatorial nay-sayers unwilling or unable to consider art that doesn’t meet their expectations often act on the belief that the work in question is “old hat,” or fails to exhibit the requisite imaginative thrill, emotional punch, formal decorum, or is not sufficiently engaged with social issues. Very often these and other criticisms are driven by narrow agendas and an insular curatorial culture that in the final analysis often panders to the worst aspects of consumerism. In this way, many directors and curators at major museums and galleries, as well as non-profit venues and other institutions, behave much like their counterparts in the commercial gallery system. The exceptions to this are, unfortunately, few and far between, and where there are differing views on what art would best serve the interests of the art-viewing public, the professionals holding these views often have little power or influence to change agendas and/or curatorial practices. Those curators and others who take note of, or at least, give the benefit of doubt to artwork that is beyond their comfort zones, are more likely those who can exercise an open mind when it comes to art that fails to meet their expectations or personal tastes, including art clearly independent of trends and styles that often advance careers and reputations. Truly independent art always challenges the status quo, but the reason for its being runs deeper than mere opposition in political and/or aesthetic terms, particularly when the art offers uniquely individual ways of regarding the world.

Being open-minded about art, or anything for that matter, usually means that a person is willing and able to consider or entertain something beyond the fold in a new way, and moreover, take it seriously. There is initially a certain amount of good faith involved when considering the value or importance of artwork that seems “out of step” with the prevailing cultural consensus, or art lacking some market-sanctioned approval. An open-minded curator, art dealer, or collector with good faith will follow through and reflect upon such artwork, including any comments about the artwork by the artist, thereby possibly initiating a deeper understanding or appreciation of the cognitive and/or aesthetic value of the artist’s individual style. The issue of individual style is central to the renewed importance of aesthetic experience, particularly when that experience enhances cognition, or better, reveals its inseparability from the aesthetic. In this respect, philosopher Paul Crowther contends that art is not a passive release, that the best of it contributes to a critical and ongoing engagement with self, others, and the world; and, that aesthetic experience is essential to our development and well-being as individuals and members of society: “Aesthetic experience invites broader questions that can develop more sustained critical consideration of who and what we are in personal and collective terms, and in our relationship to Being.”1 A lot of art with a political intent involves such questions, and yet, much of it often falls flat because it fails to fully develop a relationship to Being. Very often this amounts to art that might appease and serve ideological (and economic) interests that run counter to a more thoroughgoing progressive outlook. This leads Crowther to conclude something important about the neutralization of political art by the forces of global consumerism and how to counteract this: “We now see that, in the context of such consumerism, it is the commitment to art and second reflection upon it, as such, that is of more effective political significance. Through it, we achieve self-becoming that resists and criticizes the banalities of the consumerized world.”2 There is much optimism in Crowther’s conclusion, insofar as it speaks to a deep faith in the individual artist and cultural change. It is a position that has obvious political implications, given that it extols the critical importance of the individual artist and his or her role in cultural change, a role qualified by Crowther’s term “critical agent,” making clear that an artist can maintain real independence and develop as an individual while also making timely contributions as an engaged member of society. What is needed is a deeper sense of the value and meaning of art in relation to society and politics; it is a human need that underpins social awareness and is only effective by virtue of sharing a personal understanding and/or experience of social issues, an understanding and/or experience that people can relate to intimately. Cognitive aesthetic approaches to artmaking enlivened by the artist’s unique style can bridge the divide between individual and collective interests, particularly where political art is concerned.

Artists are a contentious lot and often downplay or deny that politics has any bearing on art and art making. Other artists fully accept that art is political and regard art as a necessary form of political engagement. I have reservations with those who would extrapolate from Thomas Piketty when he states that everyone is political in their own way, and then assumes that all art is political. My discomfort with that assumption essentially involves the possibility of a reduction of art to politics, and, as an artist, I believe that there is much more to art than this, or to paraphrase Walter Benjamin: “An artwork can only be ‘politically correct’ when it is artistically correct.” This suggests a deeper understanding of the political nature of art, an understanding that takes the way a work is made into account. If an artwork merely parrots a message, however pressing and timely, without also changing the way the work is created in relation to established idioms, for example, by modifying or enhancing existing techniques and/or methods, then the work becomes little more than a shallow form of propaganda. As mere propaganda it forgoes the radical potential of art to disrupt the status quo in more than superficial terms.

Many artists feel the need to speak out unequivocally against the injustices and inequities of a socio-political and economic system in need of overhaul if not fundamental change. Many are engaged in making art in their studios and on the streets that raise awareness of a host of alarming and persistent possibilities, including the frightening collapse of participatory democracy in the United States and around the world. Some of this art is necessarily strident in its condemnation of all the ills that have contributed to this looming threat: Institutionalized racism and white supremacy, xenophobia and anti-immigration fervor, economic injustice, voter suppression, corporate corruption, among other issues long festering in the underside of the American experiment. Art with a clear political agenda along with a ramped-up political response to this threat is needed, because to paraphrase Ben Franklin when asked, upon conclusion of the Constitutional convention of 1787, what kind of government we had, he replied: “A [democracy] if [we] can keep it.” Like many others, I recognize the challenges that we face today to keep our democracy and as an older American I will do what I can to speak out as an artist, in its defense and the United States Constitution. Our First Amendment rights are of paramount importance to artists, since most artists are generally an independent lot and given to freethinking and open-mindedness. As urgent and important as it is to call for the arts to respond forcefully to the challenges facing our democracy, I cannot stress enough that we must not lose sight of something that is fundamental to our experience of art: its value as a vehicle of self-discovery beyond or in addition to its power to inform and mobilize.

Addressing social and/or political concerns through art, particularly in concert with active protest, is an important way to exercise one’s First Amendment rights; something that art is in a unique position to accomplish. Whether through murals, poetry, performance art, or any number of means, art can express cries for democracy and justice in highly imaginative ways, grabbing people’s attention with outrage, humor, factual display, and exhortations to resist oppression and tyranny. Most artists who are also activists, provisionally or otherwise, are sincere and dedicated to both their art and the causes that they espouse. This is the case because we artists often have our fingers on the pulse of society, anticipating its perturbations, literally and figuratively. Our often-acclaimed ‘sensitivity’ is simply a matter of noticing things that others may be slow to. One of the best ways to gain some insight into the health or stability of a culture as well as its promise is to pay attention to its artists. The mainstream art world has long recognized the vision of artists in this regard and, for better or worse, capitalizes on their ability to be in the forefront of social change. However, sometimes the very recognition garnered by these artists compromises their vision, undercutting or undermining their sincerity if not political commitment. The motivations of artists are often hard to discern, but the fact is that an art of “resistance and dissent,” like anything else in a consumer society, can be co-opted and manipulated to stir the emotions of politically motivated art lovers while also making a tidy profit. The only artists perhaps above suspicion here are dedicated outdoor muralists and the like who want nothing more than to contribute something positive to their communities, often with little or no remuneration for their efforts. Their sincerity seems unquestionable, whatever their view of the function of art and its place in a free society.

Granting then that all art has a political dimension, the challenge seems to be one of deepening and then defining the nature of that dimension on an individual basis. This is a challenge because human beings, artists included, are not politically pure (or purely political). Furthermore, no art (or artist) is immune to exploitation or manipulation by either the art world or socio-political forces that would enlist art for its own narrow purposes. One might argue that this should be of no concern to the artist; once the work is made, shown and/or sold, its fate is out of the artist’s hands. While this is true, the expectations placed on the artist in this case, whether one is a politically motivated outdoor muralist or an artist represented by a commercial gallery, can be sizable. Very often what is at stake is the artist’s autonomy, a sense of independence that can be slowly eroded by either political or economic pressure, or both. In short, the value of art as a vehicle of self-discovery can atrophy under such circumstances. Artists then risk becoming mere instruments, either propagandists echoing political talking points or producers of high-end commodities, or again, more disturbingly, some combination of the two. When making or engaging with art, its social and/or political dimension should never be the primary consideration, for either the artist or the viewer or reader. When political and/or economic interests diminish or displace the cognitive aesthetic of art, it undermines the essential purpose of art: To explore the possibility of seeing the world and ourselves anew without restrictions of any kind. Exploratory art in this sense that also raises awareness of social and political issues, provided it hasn’t been coopted for political and/or economic reasons, is not only possible but is more effective because of its independence.

The political dimension of effective or engaging art has everything to do with the cognitive aesthetic that it embodies, in contrast to some of the “socially aware” art promoted by the commercial gallery system, art that usually employs the ossified structures of established idioms to convey a message. While most contemporary art implicitly embodies aesthetic ideas of one sort or another, often of a socio-political nature, a distinction needs to be made between this art and art that might also do this but at the same time puts a unique or individual spin on the means, or how the work is made. It bears mentioning that art consciously designed as propaganda, however laudable, has an obvious cognitive function as such, although that function rarely rises above that of a means to an end. Art meant to instruct along political lines supports instrumental views that often serve institutional careers more than contributing to a deeper understanding or appreciation of the vital exploratory and intersubjective importance of art in a society dominated by a consumerist ethic. On the face of it, intersubjectivity is about sharing subjective states or individual capacities within a social domain. I believe that the essence of intersubjectivity involves the embodied subject: all humans have bodies that are the foundation of awareness, and perhaps ultimately consciousness itself. Intersubjectivity is the relation or intersection between the cognitive capacities of individuals; capacities made possible by the fact that our thoughts, feelings, and imaginings are intertwined and ultimately inseparable from our bodily experience. Consciousness seems to arise from our bodily experience, to regard it in some manner as disembodied is to revive Descartes res cogitans (thought regarded as a “substance” independent of matter); an illusory notion that maintains that mind and body are distinct, and that the former could exist without the latter (a notion that is welcomed by most advocates of artificial intelligence). This ironic mindlessness is at best a distraction from a fundamental experience of being a body that thinks and feels, a way of being that is the enduring ground of intersubjectivity. Inter-subjectivity is not simply a matter of agreement between people, it’s far more basic. It involves our shared way, as sentient beings, of knowing and understanding ourselves and the world, a sense of embodiment regardless of our personal differences. Our embodied cognitive capacities are the essential bridge between self and others. Art can play a vital role in bringing more awareness to this and provide important ways of seeing the world and oneself in a new light.

Radical change, in social, political, and/or economic terms, begins, as any reasonably intelligent person knows, with a change of consciousness, which is different from a change in consciousness. Sidestepping the intractable problem of “consciousness in itself,” which seems to involve consciousness of itself, or self-consciousness, as such (and this suggests that it is futile to approach consciousness as a disembodied state); it is still possible to speak in practical or epistemological terms about how consciousness evolves. A change of consciousness involves a transformation in how we think about, perceive, and imagine the world and ourselves. It is a process that usually takes some time, often the result of years of experience and self-reflection. A change in consciousness, on the other hand, does not entail a change in the viewpoints that often drive our thinking, perceiving, and imagining the world and ourselves. The former is more radical because everything has changed, including one’s perspective or outlook. Art that enables or prompts a change of consciousness brings with it the potential of seeing the world and oneself anew, for artist and audience alike. Seeing things in a fresh light indicates the emergence of a new Being, entailing a greater awareness of one’s humanity and the humanity of others, and perhaps above all, a sense of the complexity of what it means to be human. Such art might at first seem blind or indifferent to social and/or political issues, leading to the notion that the artist is either working in a detached state or in a position of relative privilege, or both. Sometimes these assumptions are warranted, but we should not dismiss the artist and his or her art as inconsequential on that account. Art that contributes to a change of consciousness in some often goes unrecognized or is under-appreciated by others precisely because it fails to penetrate layers of preconceptions about art and fully realize its potential to be more deeply engaging. It might be argued that this is the fault of the art; that its failure to penetrate “layers of preconceptions about art” is an indication of the art’s aesthetic and/or cognitive weakness. Such a criticism ignores the basic meaning of the term “preconception:” an opinion or conception of something prior to actual knowledge or experience of it, in short, a prejudice. Not to put too fine a point on it: To substitute power where knowledge and /or experience is needed to fully appreciate and understand a work of art, always forecloses deep engagement with it. This, of course, is a political problem. Finely articulated art and elucidation by the artist as to the significance of his or her work can help, but to affect a lasting change of consciousness requires something more. It may be nothing more than the passage of time and the slowing down of a life to think, feel and see anew, thus lengthening one’s attention span. In other words, the key to a transformation of consciousness may begin in our mature ability to reflect on the nature of our own minds and the reason for our being. Some may see this approach to art as solipsistic or a distraction from the pressing social and/or political issues of the day. However, when art deepens a sense of our humanity, we are restored as individuals and social beings. What good is social and political change if we cannot change ourselves in some fundamental sense?

The focus on art as means to an end, either to present political views presumably in opposition to the status quo, or as just another career opportunity for institutional players, or worse, both, is a disservice to the intrinsic value of art and all those concerned with the loss of a vital, uplifting culture, not only many artists, but also, I dare say a large segment of the art viewing public. Art needs to be about more than elitist posturing, or paying lip service to social or political issues, or pandering to the latest fashion. Art should connect with people in ways that are cognitively and aesthetically engaging; the best of it brings pleasure in recognizing the unique ways that artists put things together and bring ideas to life.

Whether it has overt political content or not, art that has intersubjective potential can be deeply radical. Such art will not, in principle, strive to be a critique of the status quo, this is not its mission. The point is that art out of step with the prevailing cultural consensus while also revealing intersubjective potential is often deeply antithetical to the values of the status quo by virtue of its eclecticism and/or individual style. It is often art that is inherently oppositional. If the work is stylistically unique, expressing an individual viewpoint, then this inherent quality does not preclude such art from also taking a stand on the social and/or political issues of the day. In fact, it may be that such art is better positioned to make a lasting impression and is therefore more effective in advancing social and/or political viewpoints that might otherwise be taken for granted.

I will close with an incident in the early 1970s, when as a young political activist. I joined a picket line in Oakland, California organized by a radical leftist group protesting the racist practices of a local supermarket. I was an erstwhile poet and member of the Vietnam Veterans against the War (V.V.A.W.) picketing in support of Venceremos, a revolutionary organization in solidarity with Cuba. In those days I struggled to balance my political activism with art making and the writing of poetry, much of it that was not overtly political. I was keenly interested in language from a Conceptual art perspective and was writing poetry with a decidedly “subjective” and metaphysical orientation. I remember attempting to share a couple of my poems with one of the leaders of Venceremos and his icy response to them, which resonates with me to this day. To paraphrase, he said: “This poetry is not revolutionary and therefore irrelevant in terms of our struggle.” I was both stunned and disheartened by his response, and clearly naïve. It was an instructive encounter with ideological rigidity, a malady that infects minds on both ends of the political spectrum. Art then, as now, is destroyed when reduced to mere propaganda. The struggle for justice, equality, and human dignity must always encompass a broad array of aspirations that might contribute to the betterment of humanity. As some believe, perhaps all art is, broadly speaking, political. But the lesson that I learned and subsequently rejected that day on the picket line: When art fails to make a politically revolutionary (or socially committed) statement, it is part of the problem and not the solution, remains one of the defining moments of my artistic life. I am no less progressive in my political views today than I was in the early 1970s. What has changed is the view that if all art is essentially political, then perhaps we need a fresh understanding of politics in relation to art.

Footnotes:

1 Crowther, Paul. The Aesthetics of Self-Becoming, How Art Forms Empower (London: Routledge, 2019, p. 151)

2 Ibid., 151

Why I Make Art

There is in stillness oft a magic power

To calm the breast when struggling passions lower,

Touched by its influence, in the soul arise

Diviner feelings, kindred with the skies.

— John Henry

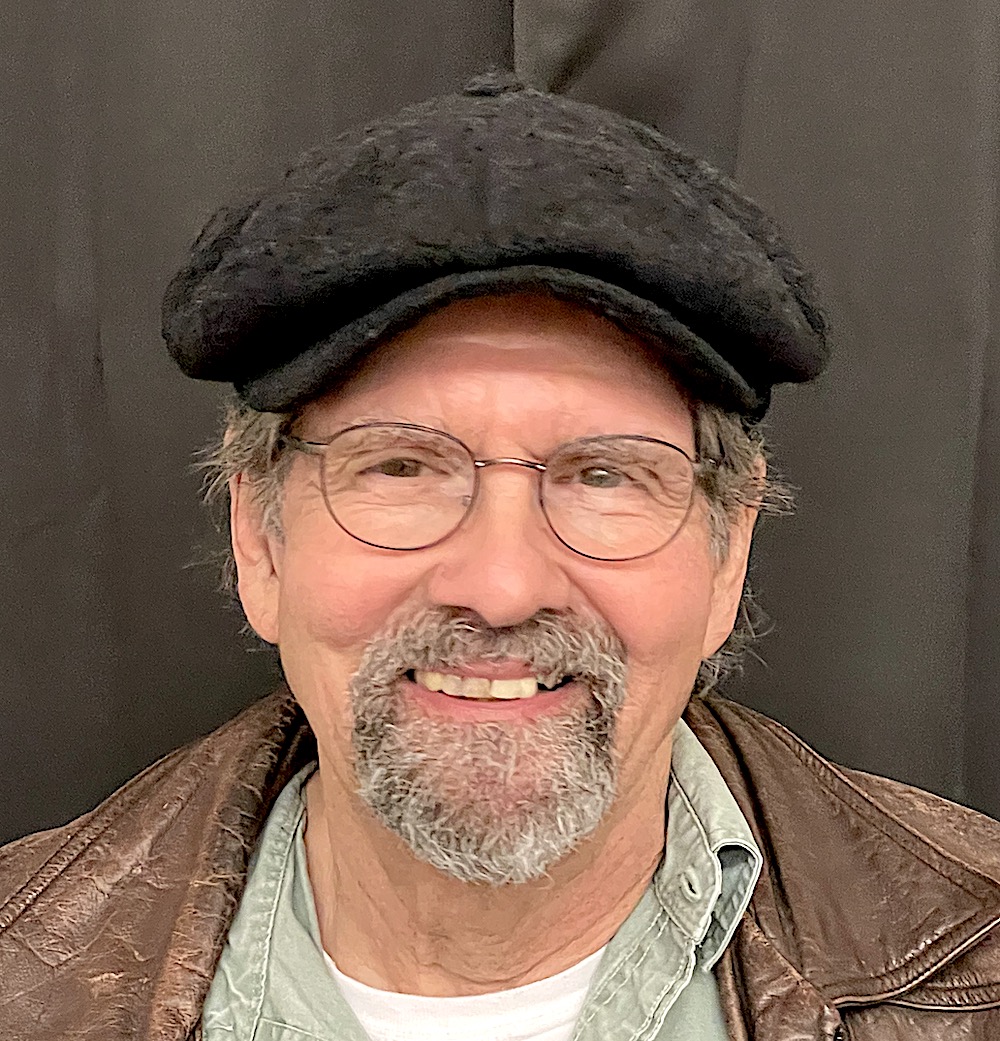

I am seventy-four and have been making art for nearly 50 years. As I have now entered my “golden years,” I feel a need to reflect upon my career; to take stock of both shortcomings and accomplishments and to share something of my life with others. The following synopsis is therefore meant to encourage not only artists my own age who might feel left behind, or unappreciated, but also perhaps even a younger generation facing a difficult and highly competitive vocation that is testing their resolve and creative potential.

Having moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1960s after a stint in the military, I enrolled in art school at the California College of Arts and Crafts (now the California College of the Arts) in the spring of 1969. I soon discovered that I was unsuited for academic life, dropping out after only one semester to continue learning on my own, while also becoming emersed in the anti-war movement. By the mid-1970s I was involved on the periphery of the San Francisco art scene and eventually gained some modest recognition (an exhibition at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1975, followed by other Bay Area venues), as well as securing a major grant: an NEA Visual arts Fellowship in 1978. At mid-career I garnered the attention of a few artworld heavy weights: Conceptual artists Sol Lewitt and Lawrence Weiner, and philosopher, Arthur Danto. Being an uncredentialed artist, my resume is not extensive, as I have not had all the opportunities that a degree makes possible. Nevertheless, my work has been included in a few group-shows on both coasts over the years. These inclusions, however, never led to representation by a commercial gallery or further group show invitations from museums and other exhibition venues. There were some hard years for me in the 1970s into the 80s; bouts of homelessness and depression, and substance abuse, but I never lost faith in my art or myself.

In 1987 I met a wonderful and caring woman and fell in love. I soon after left California and settled in Rhode Island, joining my angel in a small cottage in Narragansett. Back on my feet and with a small basement studio I was making art while holding down a job as a house painter. With renewed confidence after winning a Pollock-Krasner Fellowship in 1990, I began approaching commercial galleries, “alternative spaces,” and museums. During these years, I also applied for numerous grants: among others, an NEA Artist’s Fellowship; a Joan Mitchell Foundation grant, a Guggenheim (with excellent references), and a Gottlieb Foundation Fellowship, all unsuccessful. I repeated this process numerous times. But ever so slowly, I began to sour on what seemed like endless rejections. One of the last applications was a Pollock-Krasner Fellowship in 2009. All my endeavors to secure funding after the Pollack-Krasner Fellowship in 1990 were unsuccessful. It almost felt like being blacklisted, as if, however accomplished the work was, it didn’t matter because apparently, I wasn’t making the sort of art that interested these institutions. All this effort with no results led me to conclude, like some others, that the system was largely unresponsive to those artists without an inside track with those promoting and selling art, even accomplished artists recognized by art world professionals. To make a long story short, I eventually gave up applying for grants and making inquiries about exhibition opportunities. While my work has found some local and regional recognition since that time, other than a modest imprint provided by my website, it remains largely overlooked; lost in a sea of market-driven mediocrity.

Discouragement has certainly played a role in my giving up on grants, galleries, and museums. But more importantly, at some point around 2010, I asked myself a fundamental question: Why do I make art? With little recognition and no reward, why continue doing something that seems so fruitless? I struggled with these questions for some time, until I remembered what moved me as a young artist; a desire to explore what it means to be alive. I realized that the basic reason that I make art is that it gives my life meaning and deepens a sense of being in the world. As we get older a simple fact sets in: We only have so much time and energy to devote to our calling, whatever that might be. After the first decade of the new millennium, I reasoned that I would invest all my time and energy in art making and accept the relative obscurity of my situation. It was the right decision. And yet, I do wonder about my artistic legacy and what will become of my work when I’m gone. This is much more than a personal problem. This society has never treated its artists and poets with the respect that is their due. Frankly, my disappointment about this has been transformed over the years into a deep sadness, for myself and others. But this transformation has led to an even deeper realization: That the pain that we carry can be harnessed and channeled into positive endeavors resulting in outcomes that can enrich the lives of others. For creative people this may be the most important reason to continue working no matter what, knowing full well that there will be bumps in the road ahead.

Every now and again my inspiration ebbs and I begin to feel as if my creative life is coming to an end. As this dark moment descends, I also begin to question the significance of not only recent work but even the work of a lifetime. The spell of this uncertainty is sharpened by the fact that I have not shared in the worldly success of other artists my age. Whether real or imagined, I sense being judged irrelevant, perhaps because of my years, or my refusal or inability to respond to art world trends and the concomitant drive to exhibit or market my art. This perceived judgment of irrelevance spawns a cloud of dejection that would paralyze some artists, rendering them impotent. For some of us, however, the dejection that results from this perception spins a web of confusion amounting to a futile attempt to counter the darkness that only seems to draw one deeper into its grip. The challenge is, of course, one of will: The artist must accept this darkness and somehow keep his or her wits about them.

This self-analysis is important and necessary because the dejection that I sometimes feel never reaches the point where I question my identity as an artist, although it does give rise to a profound sense of alienation. This painful feeling of being left behind, of being nowhere, paradoxically motivates or energizes the will. I determine to prove to myself that the creative spirit is alive and well. But will, that most personal form of power, is nearly useless because one usually just goes through the motions and suffers one creative false start after another. But perseverance and such false starts can unknowingly contribute to one’s creative process. This floundering might then lead to a reassessment of past false starts: Half-realized ideas that can offer clues as to the presence of the creative spirit. By willfully following these traces I slowly begin to regain my footing and sense of purpose. And then, from the depths something miraculous: That shining face announcing the arrival of wonder. Something greater than mere will once again moves my soul. I feel alive, whole, or complete, comfortable, and confident. I am the artist that I have always been.

— Paul Forte, May 2021

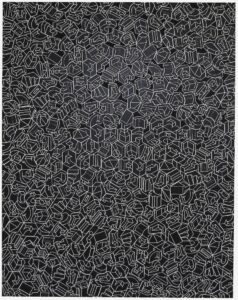

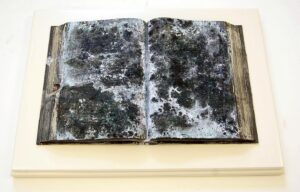

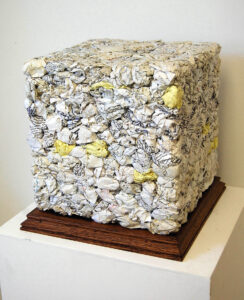

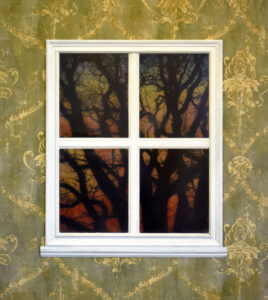

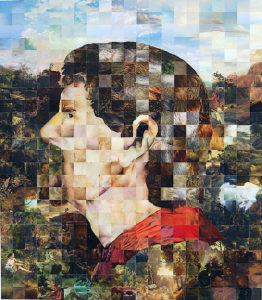

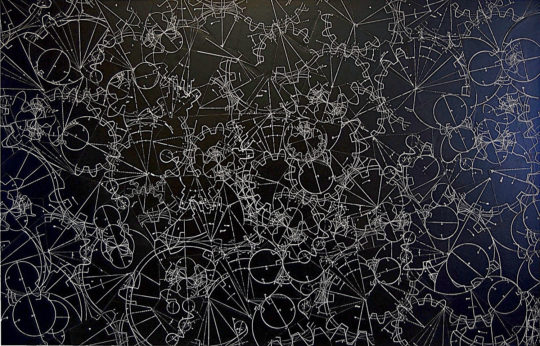

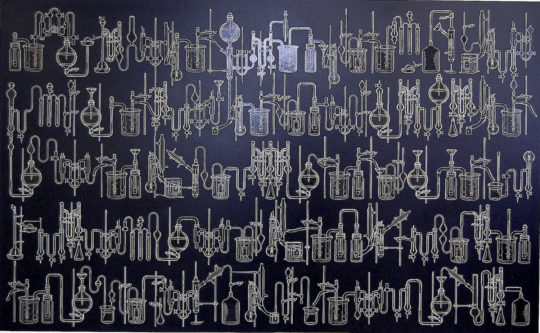

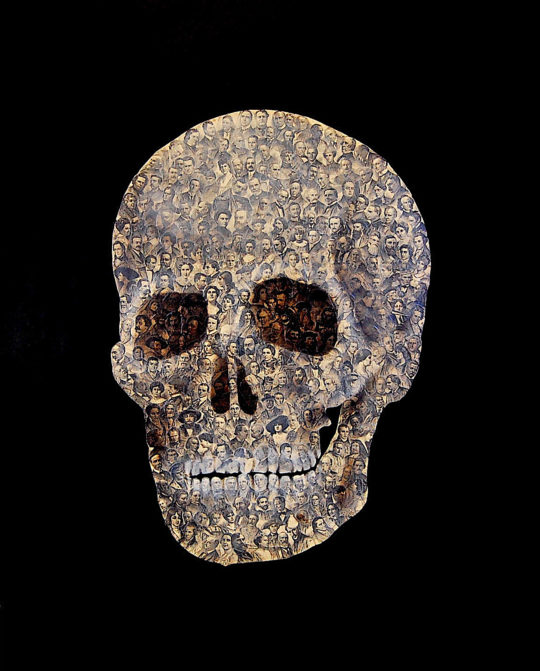

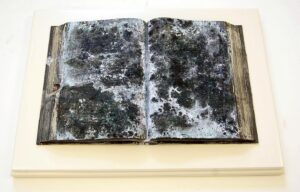

Poetic Objects:

The Commonplace Transformed

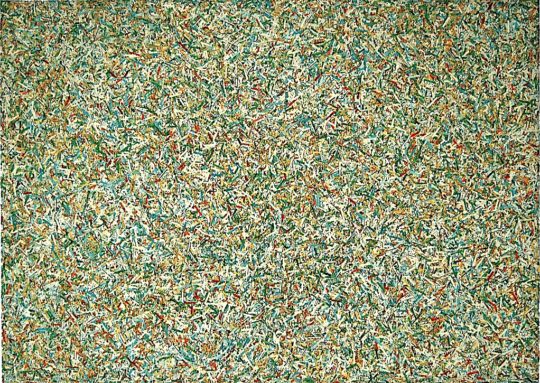

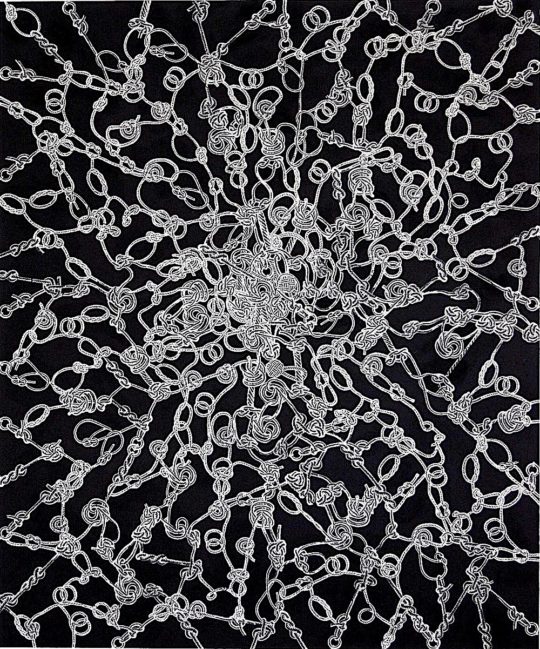

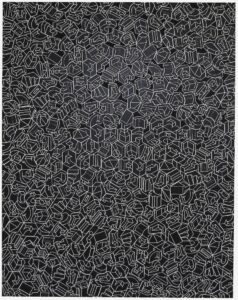

An experimental approach to art making, coupled with an abiding sense of the poetic, are the hallmarks of my art. It is an art that has explored this approach and sensibility through a variety of media and artforms over the years: text works, poetry, artist’s books and bookworks, performance art, drawings, paintings, collage, assemblage, and constructions. Central to much of this work is the use of found or readymade material. While this practice is widespread, it doesn’t always lead to compelling results. What seems required is an experimental and poetic approach to art making that makes ideas clear and palpable. This is where cognition or the cognitive enters the picture. The clarity and concreteness of an artwork stems from an active imagination and an awareness of the many ways that we think, see and feel about things. Poetic ideas can be developed from found things by paying attention to and utilizing their salient or unusual characteristics. In my work, the ideas thus realized are generally of a symbolic and or metaphorical nature: poetic ideas expressed in either visual or verbal terms, or both. Given the broad range of my art making over almost fifty years, categorizing it in terms of recognizable media or artforms serves to highlight its ongoing experimental nature. Many of the artworks represented here are hybrids in the sense that they could be categorized in more than one way. How a work is classified depends upon what aspect of the work is emphasized. A particular artwork might have elements of both a text work and a collage, or elements of both a bookwork and a construction. Any categorization of artwork is somewhat arbitrary, but it is a helpful tool, especially when the artist seems to have no appreciable “signature style.” Considering the experimental nature of much of my work, it follows that many of the artworks have inspired written commentaries; musings on the processes of their making and offering possible interpretations as to their meaning or significance. For the creative artist, creativity doesn’t end with the artwork; it is an interrelated or integrative process bringing to bear perception, imagination, thought and feeling, for artist and audience alike.

Education