This Month’s Insider’s View: Science versus Provenance

The art world is pretty sophisticated when it comes to establishing authenticity. The first step sees the professional sellers — dealers and auctioneers — engaging a triumvirate of experts who provide stylistic interpretation, provenance, and condition reports. An art historian who is the leading expert on the artist examines the work and anoints it as authentic. A researcher tracks down and confirms its history of ownership. And the conservation expert’s condition report gives it a clean bill of health. But if any of these three reports come back negative, run don’t walk. At that point there’s no reason to go to the expense of art forensics.

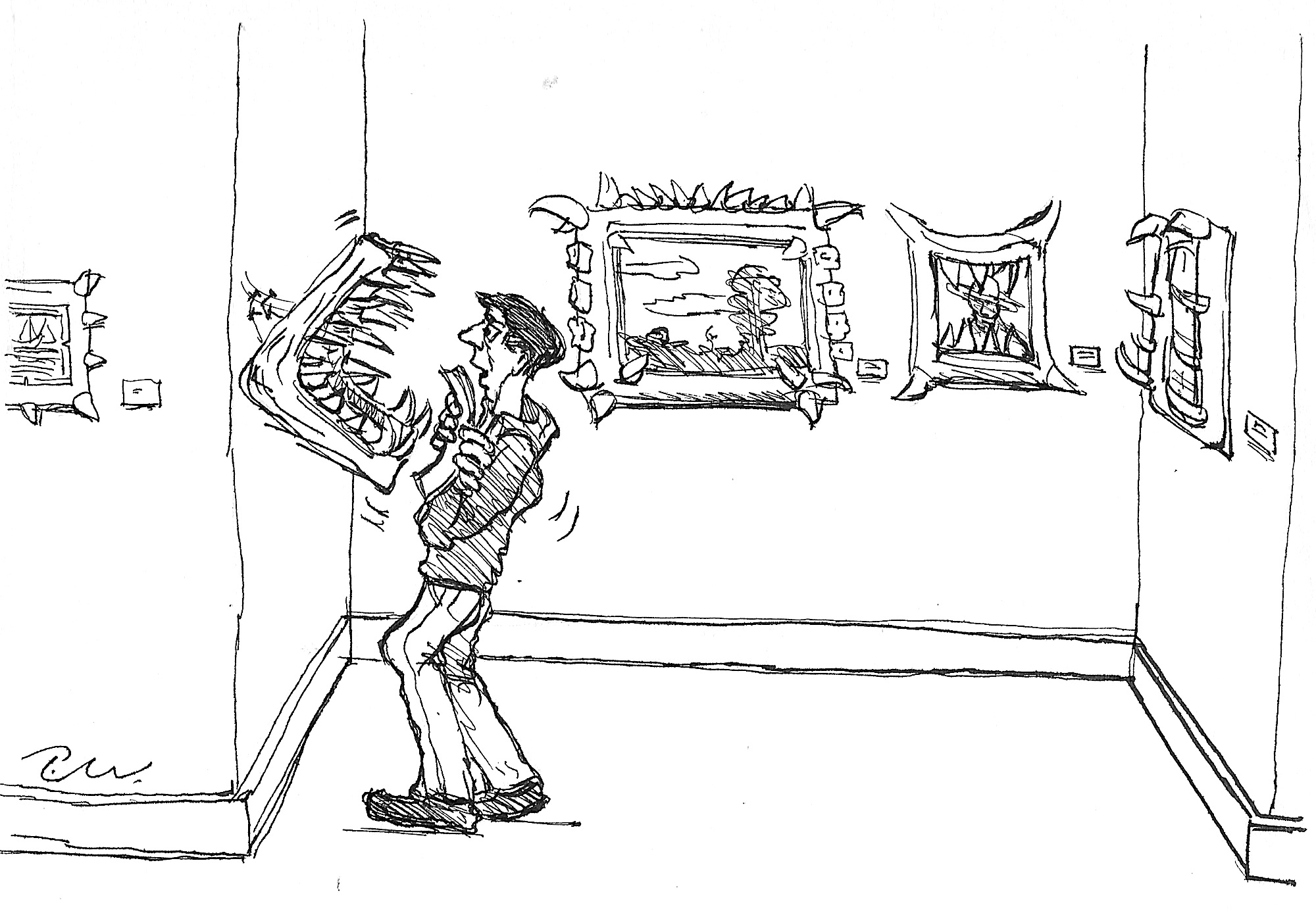

“Everything has teeth!”

From Peter Falk’s ongoing Illustrated Dictionary of Art Market Argot.1: phrase used to describe a painting or group of paintings when a lack of authenticity is strongly suspected (cartoon by Tina Waring)

End of story?…maybe not. What makes the headlines is another cautionary tale because caveat emptor was at play. From time to time all three reports and letters of authenticity have been later over-turned by forensic testing. That’s when the world’s leading auction houses and art galleries of fine reputation not only suffer egg on their faces but become embroiled in high-profile lawsuits.

But how do you know when forensic testing is essential and to whom you should go? There are several laboratories in the U.S. known for their excellent work, but since I have direct experience with several cases conducted by Microtrace in Elgin, Illinois, they are at the top of my short list. Later, I’ll reveal one of the cases I brought to them that ended in tragedy.

The point is that when it comes to forgeries, it’s all in the science. Art forensics has been playing an increasingly crucial role in the art market. As you’ll learn, forgeries are not limited to those multi-million-dollar scams for paintings purportedly by the most famous artists. Forgers inevitably become incentivized to ply their craft once an artist’s works start pushing toward and beyond the $50,000 mark at auction. It’s almost always after the damage has been done that forensic experts like Microtrace are asked to step in and reveal the scientific evidence about how the unwitting buyer was duped. The greater the price gets, the greater the reason you shouldn’t wait for a controversy over authenticity to arise.

No better example illustrates this need more than the case studies at Microtrace, whose reputation for quality microanalysis goes back decades. They have worked on artworks from all periods, including those attributed to 20th century artists. However, professional discretion prevents them from discussing the specifics — especially since their highest profile cases have hit the news. They will say that when it comes to paintings, their approach starts with the pigments. From there, they dive deeper into binders, additives, and the supporting strata. Depending on the client’s question and the work itself, they may also look for other trace materials that could contribute to provenance.

Forensic analysis of fine art is at such a high level that it’s virtually impossible to slip a forgery by a team like Microtrace — particularly for works dated before the 1950s. Then how did the world’s five greatest forgers of all time succeed so brilliantly over so many years? After all, it’s only fairly recently that their deceits were exposed and made international headlines. Their stories are incredible. One of the most infamous in American history was Ken Perenyi, whose multi-million-dollar roll carried on for thirty years, as documented in Caveat Emptor: The Secret Life of an American Art Forger (2013). In 2016, Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese immigrant living in Queens, took the limelight after creating a series of multi-million-dollar Abstract Expressionist fakes (including Pollock, Motherwell, and Rothko) that were sold through the prestigious but now-defunct Knoedler Gallery in New York. In England, Tom Keating created more than 2,000 forgeries of works from more than 100 artists — and documented them in The Fake’s Progress (1977). More recently, he was eclipsed by a fellow Brit, John Myatt, who has been described as committing the biggest art fraud of the 20th century — as recounted in Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art (2009). Meanwhile, Wolfgang Beltracchi, a German artist living in France may well deserve the title of king of forgers. He painted more than 1,000 forgeries in the style of valuable modern masters. In the captivating 2014 documentary film — The Art of Forgery — he has been described as the “forger of the century.” It was forensic science that ultimately exposed each of the five famous forgers described above. Spontaneously, the leading auction houses and galleries who were involved fell hard in the press.

Microtrace is in the business of delivering accurate science, but sometimes that can double as bad news for its clients. This is not your ordinary laboratory because they know that every case can present unique problems. Their team of experts has experience with almost every type of material found on the planet — from organic to inorganic, from natural to man-made, from solid to liquid to volatile. In the fine arts, they collect samples of both the pigments and their ground and analyze their microscopic and nanoscopic properties. In addition to the identification of pigments and binders this includes the composition of every type of fine art ground material or support, including fibers of a canvas, cotton, wood, cardboard, paper, or even synthetics. They employ an arsenal of tests for examining these materials, isolating and analyzing incredibly small particles. Then they interpret the subtle microscopical, chemical, and elemental differences and report on the significance of the results in comparison with those materials that have been verified as having been used by the artist.

That’s the segue to my earlier reference to a case that ended tragically for one of my own clients. I was asked to broker a collection of Russian Constructivist watercolors from the 1910s–1930s. They were brilliantly executed and came with a romantic provenance that could have been part of the 1965 Doctor Zhivago movie. Knowing the Russian art market has long been fraught with fakes, the style and period immediately raised a red flag. I told the owner they just “smelled wrong.” Even though the owner was very confident about their provenance I explained that there was only one way I could help him. He agreed to let me bring a group of the watercolors to experts in this field for their examination. Afterwards, I had to deliver the bad news that their strong skepticism had only hoisted my initial red flag to the top of the pole. Despite these negative opinions, the owner remained adamant that his provenance was factual and was certain that he would be vindicated by the ultimate proof: forensic testing. Accordingly, I brought several of the watercolors to Microtrace. Their forensic testing conclusively proved that certain of the pigments did not exist until many years after the works’ dates. The owner was devastated. What I did not know is that he had not only put his entire life savings into this large collection but was also on the brink of bankruptcy. Sadly, a few months later he committed suicide.

Forensic testing shouldn’t have to end in such tragedy. Nevertheless, how did the aforementioned five greatest forgers thrive in an era when a leading laboratory like Microtrace could have illuminated the truth? The short answer is blindness and greed. Those who stood to profit never bothered to double-check with the scientists before they urged their clients to commit serious capital. The opinions of the triumvirate of experts was enough to satisfy them. This leaves only two conclusions: They were either blindly sloppy; or, if they had any suspicions they intentionally looked the other way.

Yes, those written opinions from art historians, researchers, and restoration experts are usually accurate. But when any aspect of an artwork appears to need clarification, I’ll go with science as the ultimate arbiter every time.

Peter Hastings Falk, March 2019