The big surprise — and what makes this story so different — is that during one special span of his career Simatos was also an itinerant painter aboard a trans-Caribbean luxury cruise ship. As Reiter continued to find more portraits, he realized he was forming a time capsule of celebrities, royalty, and the haute bourgeoisie of an era spanning from the 1920s to the late 1970s. Simatos met many of his sitters while on the Promenade Deck of the S.S. Homeric. The ship belonged to the Home Lines company, based in Genoa, Italy. This was during an era when the cruising industry was far different than it is today. Ship logs reveal that Simatos pursued this engagement as artist-in-residence from about 1955–1967, most years making several mid-winter excursions. In short, Simatos was the first artist to capture a unique slice of the characters who populated mid 20th century culture.

The big surprise — and what makes this story so different — is that during one special span of his career Simatos was also an itinerant painter aboard a trans-Caribbean luxury cruise ship. As Reiter continued to find more portraits, he realized he was forming a time capsule of celebrities, royalty, and the haute bourgeoisie of an era spanning from the 1920s to the late 1970s. Simatos met many of his sitters while on the Promenade Deck of the S.S. Homeric. The ship belonged to the Home Lines company, based in Genoa, Italy. This was during an era when the cruising industry was far different than it is today. Ship logs reveal that Simatos pursued this engagement as artist-in-residence from about 1955–1967, most years making several mid-winter excursions. In short, Simatos was the first artist to capture a unique slice of the characters who populated mid 20th century culture.

This unique discovery begins in 1965 when Reiter’s parents — Toby and Harry — an upper middle-class couple from suburban Long Island, were aboard the Homeric. It’s important to point out that the business of mid-20th century luxury cruising exuded an aura quite different from today’s cruise industry with its enormous floating hotels — mega-ships numbering in the hundreds and carrying millions of passengers around the globe. Today, no one with Simatos’ role would be found on board except, perhaps, a photographer. It was at the turn of the 19th century — Mark Twain’s “Gilded Age” — when luxury cruising reached its pinnacle with seven improved luxury ocean liners. Twain even lived to read about the ill-fated Titanic and the Lusitania. But in 1965, when Toby and Harry boarded the Homeric, luxury liners were just recovering from having been virtually snuffed out by two world wars. A striking example of this occurred in 1942, when the United States, attempting to support its war effort, commandeered the French super-luxury liner, the S.S. Normandie, while it was docked in New York Harbor. During its conversion to a troop ship, this Art Deco masterpiece caught fire and sank. The ship was raised, but the damage proved so extensive that it was scrapped. Later, some of the luxury cruise lines managed to thrive by promoting their voyages as vacation-adventures in opulence and pampering. As artist-in-residence, Simatos promised that a passenger’s experience would always be remembered with a unique keepsake.

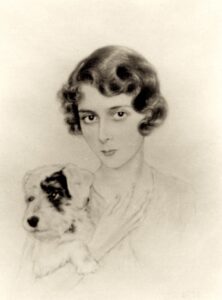

Simatos was born in Greece. To date, his earliest commissioned portrait (ca.1923) places the young artist 1,500 miles northwest, in Monte Carlo. Many more commissions would follow, and his success allowed him to maintain residences in both Cannes and Paris. It was likely in one of those cities where he became best friends with Salvador Dalí and painted his portrait as well. Reiter’s collection includes portraits of many actresses, with the location identified as “Cannes.” These are dated just after World War II when the city’s film festival was building momentum. By the early 1950s, momentum had made the Cannes Film Festival an even greater international event. Simatos welcomed its booming stature, especially since it created an increasingly larger pool of prospective commissions from many well-known actors, actresses, and auteurs.

After Simatos passed in 1979, the dissipation of his legacy was assured — hidden away in the homes of his numerous patrons. Considering the course of a fifty-year career, it’s reasonable to assume that his life’s work exceeded a thousand original portraits — yet most of them remain undiscovered. Reassembling enough of these portraits to make sense of his accomplishments would seem a daunting and nearly an impossible task. Plus, despite his notoriety, Simatos never documented his work. Owing to the nature of portrait commissions, it’s unsurprising that exhibitions of his works have never been identified. Plus, it appears that he never gave any interviews to the press — all but ensuring that the story of his life and career would be lost to the ages.

After Simatos retired from his engagement as artist-in-residence on the Homeric, there is no record of any other portraitist picking up where he left off. His legacy, now being restored by Reiter, offers intriguing insights. The dearth of biographical information about the artist is mitigated by the story behind each portrait. This research begins with identifying the sitters. One piece of the puzzle is provided when faces are recognizable. Simatos helped with this identification by occasionally writing the sitter’s name on the verso. Reiter estimates that of all the portraits he has come across, only about half of them include a date and/or a location. Paris and Cannes appear most often. Many other locations were noted, including Monte Carlo, Monaco, the Ritz-Barcelona, Cap d’Antibes, Sanremo, the Madeira Islands, Portugal, Nice, Patiala City, India, Beaulieu, England; and of course, the Homeric. Reiter remains in pursuit of all lost Simatos portraits. As more are revealed, a fuller picture of the life and work of this mysterious artist will emerge. Determined to memorialize Simatos’ legacy, Reiter has written an essay — “My Mother’s Portrait” — telling the ongoing story of his serendipitous discovery of the artist behind these portraits — a story that never ceases to inspire, motivate, and entertain him.

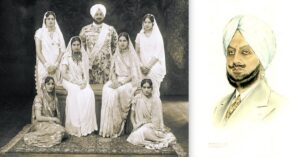

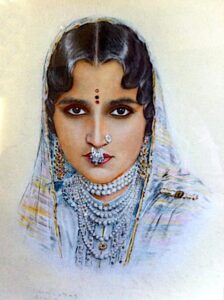

The Maharaja of Patiala

One patron of special note was Sir Bhupinder Singh, Maharaja of Patiala, India [1891-1938]. Reiter discovered that the Maharaja, instead of being referred to by the traditional title, “His Exalted Highness,” was instead known in the press as “His Exhausted Highness” owing to his prolific procreation. Reiter explains: “The Prince fathered at least 62 children in consort with his 10 Queens and upwards of 300 concubines – perhaps, explaining why, in 1938, he passed away at the young age of 46. His excessive eating habits didn’t help much, either, as sources reported his consuming a 24-egg omelet for breakfast, a luncheon of soup made from the stock of 24 snipes — and 40-50 boneless quails as a pre-dinner snack. But the Maharajah’s boundless excessiveness proved very helpful to our young artist. Starting in the mid-1930s, the Prince commissioned Simatos to memorialize — in pastel — every member of his family, plus the myriad of house guests who would drop by his 450-room palace. This was, by far, Simatos’ most expansive project, taking him three years, off and on, to complete. Another benefit of being the Maharaja’s artist-in-residence included being chauffeured around Patiala City in one of the Prince’s Rolls Royces (from his collection of twenty). Most important, this major commission embellished Simatos’ reputation with an air of notoriety, helping to launch his career as “the” portrait artist to royalty, nobility, celebrity, and those just plain old rich.”

The most elaborate example of the Maharaja’s persistent overindulgence is known as “The Patiala Necklace” — one of the most extraordinary pieces of jewelry ever created. In 1928, the Maharaja commissioned Cartier to fabricate this masterwork. It took three years to complete at a cost of $25 million. Its setting held 2,930 diamonds. Its centerpiece was the world’s seventh-largest diamond, a 234-carat yellow De Beers. Joining it were seven other major diamonds, ranging from 18 to 73 carats, plus several Burmese rubies. Worn by The Prince until his death in 1938, it was last seen in public in 1941 when worn by one of his sons. Around 1948, the necklace mysteriously disappeared from the Patiala National Treasury, rumored to have been sold off for tax reasons. In 1982, the De Beers diamond surfaced at Sotheby’s in Geneva where it was auctioned off for $3.16 million. Then, in a final twist, in 1998 a Cartier associate found the necklace in a second-hand jewelry shop, in London — stripped of all its major stones. Cartier bought the remains and restored it using cubic zirconia and synthetic diamonds.

More Gems…

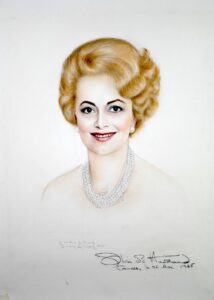

Below is the case of another diamond necklace. This portrait was painted in Paris in 1954. It made a 21st-century appearance at auction as proof of provenance for the sitter’s 69-diamond rivière necklace. The value of necklace put it out of Reiter’s reach, but after the sale, the auction house kindly connected him with the buyer who was willing to part with the portrait. The sitter is Mrs. Coussée, whose family were innovators in manufacturing plastic furniture in post WWII Europe and owned large factories in Ronse, Belgium.

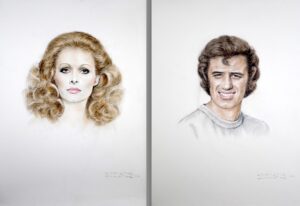

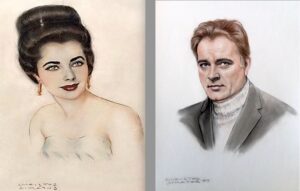

… and More Celebrities

… and More Celebrities

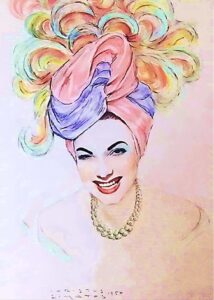

… and many “Glamour Girls”

The entire cruise delighted Toby Reiter — and she especially enjoyed her sittings with Simatos. Upon her return home, she shared with her son her distinct memory of the straightforward process Simatos implemented to capture her likeness. There were just two sittings. After the first, Simatos returned to his shipboard studio where he was assisted by a Polaroid image taken as an aide-memoire. He then completed the portrait during the second, and final, sitting. Future passengers on the Homeric would have only a few more years to sit for Simatos. It is most likely he retired to Cannes during the 1970s. That was when fleets of jumbo jets forced the cruise industry to change and adapt by appealing to the middle class. The earlier era of luxury cruising — along with a singular portraitist-in-residence amenity — slipped from memory.

While Reiter’s essay, “My Mother’s Portrait,” is personal, it is also an example of cultural journalism. In addition to investigating the artist’s famous sitters, his research and storytelling provide rare glimpses into the lives of many lesser known but nonetheless fascinating characters whose accomplishments would likely have gone largely unrecognized. Reiter’s essay also documents his global art treasure hunt and provides details on the lives of Simatos’ sitters, many of them long forgotten. His essay makes an appeal to all art hunters, especially those who haunt flea markets and antique shops, urging them to become familiar with Simatos’ portraiture and to join his hunt. He also puts out a call to the public, at large, asking for help in identifying the anonymous sitters seen in many portraits. And, when newly discovered portraits arise, Reiter intends to travel to meet the owners and document their acquisitions for his catalogue raisonné. Equally important, he intends to document their stories with a camera crew with a Q&A between Reiter and his fellow hunters. In addition to film (documentary and docu-series), Reiter’s story is highly adaptable to various forms of print media — magazines, newspapers, art journals, and, of course, a monograph in book form.

It is likely that art hunters have already come across other Simatos portraits but had not bothered to research their finds, simply because he is not listed in biographical dictionaries and other art references. After all, caution increases exponentially if one can’t easily find an artist’s bona fides. Without the security of a positive background check, interest in looking deeper usually fades. Numerous artists have suffered the cruel fate of falling through the cracks of art history. Relegated to a purgatory of marginalization, they fall victim to our collective memory loss — if, indeed, they had ever achieved some recognition in the first place. Most wind up in the dumpster. Without carefully looking at art, or being genuinely curious, it becomes too easy to quickly condemn a lesser-known artist’s work as lacking quality, historical significance, and value. Sadly, this condition of collective ignorance has proven ruthlessly repetitive in art history. Reiter vividly recalls the moment when his mother’s portrait sparked a journey of investigation. It was an epiphany, without which the Simatos signature would likely have remained just another undecipherable scribble beneath another unidentified face. Thankfully, this undeterred detective has added a significant portraitist to the chronicles of art history, illuminated his life’s work, and revealed the intriguing and largely untold back stories of his sitters.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Epilogue

This essay tells as much as is currently known about Simatos, illustrated with a selection of portraits with intriguing back stories. You can see more portraits by clicking on the tab, “The Portraits.” Moreover, Reiter’s essay — My Mother’s Portrait — features many more portraits along with their revealing histories. Most, but not all, of the portraits seen here were drawn from Reiter’s large collection. This exhibition presents a small representative selection. If you would like to read Reiter’s full essay, please send us an email and we will be pleased to forward it to him for his direct response.

Reiter explains his purpose:

“My Mother’s Portrait is of general human interest — a version of the age-old headline — ‘Man Finds Priceless Art in Dumpster’ — appealing to the near-universal fantasy that any one of us can, and sometimes do, stumble upon lost or undocumented (art) treasure. My story is truly multidisciplinary — perfect as content for a Discovery-type or arts, culture, history, or news media outlet — for a documentary, a docu-series, or a feature story. Partnership with a relevant sponsor in a branded entertainment agreement is also a possibility. My story, combined with Peter Falk’s essay, could even be transformed into a piece of historical fiction.”

Note that portraits drawn from Reiter’s collection are available for exhibition.