By Wynn Parks

Brett Taylor was one of the far-flung children of the Sixties. In the era of high spirits and social revolution, when his peers were opting for demonstrations, and the excitement of street politics, Taylor chose a more classic road to romance. He set off to experience the wonders of the wide-world; to live large; to jump off into the deep end — No guts; no glory! — with Byron and Burroughs.

He needn’t have, he was already established in Tyler School of Art circles as a young, hot-shot artist. But instead of a career as an academic darling, Taylor dreamed of broader recognition, living in the Mediterranean, where one could pursue painting in the spirit of Picasso and Braque; and meantime, to create a school of art from which students would go away never seeing their world the same again.

A half century later, the images coming out of Taylor’s little-known Odyssey reach us like the light of a star that no longer exists.

Taylor was born in Florida, on the 2nd of March 1943, the son of Henry White Taylor, a well-regarded portrait artist from Philadelphia. The elder Taylor died when his son was seven months old. Taylor’s mother, Mykia, let her son know from an early age that in him she recognized both his father’s love of wordplay, and talent for painting.

In 1965, while half of his male peers sweated in Vietnam and the other half sweated their student deferments, twenty-two-year-old Taylor was teaching printmaking at Cheltenham Art Center in Philadelphia. Though he’d established himself as the Director’s protégé, the “non-vital” nature of his work wouldn’t have provided him with much immunity from the draft. Yet, Taylor’s number never came up. His luck held long enough for him to get married and complete an advanced degree at Tyler School of Art, a part of Temple University. Despite his seemingly charmed life, by March he’d opted to drop out of his tenure-track lifestyle, and go, not for Canada, but Greece. It wasn’t really a case of “dropping out.” That would have been to run away from something. Taylor was chasing.

Taylor was abetted by Gladys Wagner, his boss/mentor at Cheltenham, who ran magazine ads, seeking applicants in a summer arts program, which styled itself The Aegean School of Fine Arts.

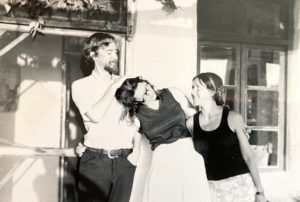

Dazed by the whirlwind of graduation, marriage, and departure, Taylor and his wife, Nina, bought a Greek-English dictionary, along with a handful of language tapes, and sailed from New York aboard a Yugoslav freighter. With time running out to locate a base of operations, Taylor and Co. set out to scout the Aegean islands on a Greek ferry. It was a squeaker: a scant three weeks before the school’s first scheduled session, Taylor hurried out wires instructing students that, from Athens they should meet on the island of Paros.

Paros, in 1966 was largely a turn of the century farming and fishing community in the Cycladic group; a twelve by six-mile mountain-top in the sea; obscure in modern-day awareness, except for its remarkable marble, and as the birthplace of the West’s original lyric poet, Archilochus.

From an approaching ferry, the island often seems to float between blue sky and blue, dolphin-spawning waters. Closer in, the geography is rocky and brilliant with an intense, perspective-shredding light. Steaming into harbor, the organic architecture of the port village, Paroikia, is a Cubist’s vision.

Taylor never considered himself a businessman, nor necessarily considered being one a virtue. But Greece, in 1966, was under a home-grown, military junta. So, aided by his Greek-English dictionary, and the country’s chilled economy, Taylor engaged the best accommodations the Aegean School would ever have: a large, old house, built by the Venetians with tall ceilings and windows; perfect for studios. The building included a wine cellar and an enclosed courtyard of five or six hundred square feet.

Within a few days of his first classes, Taylor realized the school was going to fly. The combination of relief and elation was intoxicating. In the spirit of the times, and on the principle that you can lead-a-horse-to-water, Taylor refused to play the academic “game” of “requirements.” Much was offered, but nothing, except tuition, was mandatory. The exotic lifestyle invariably put the students’ perceptions on “full gain.” The result was often an unimagined new perspective on themselves and their artwork. Speaking of the phenomenon, Taylor would grin hugely and say:

“It’s like selling ambience! All I have to do is fuel the process with art supplies, aesthetics, and group interaction!”

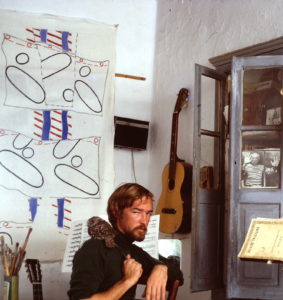

During those early years, Taylor, himself, found new direction in his work since leaving the U.S. In “Studio” he painted for the students, to illustrate points about “spontaneity,” on occasion impatiently dipping his brush into liquid medium; then into powdered pigment, and from there to the canvas, where he mixed and painted at the same time. So that, at the center of the school’s “hot” status, lay his own ferment.

Despite Taylor’s own state of grace, however, Nina wasn’t adapting quickly to the simple life. Despite her husband’s exhilaration with the nineteenth century life of kerosene lamps, and supplies borne home on their donkey, Marcel… and perhaps to avoid the distraction of family responsibilities, Taylor temporized on his wife’s desire to genetically start her own creation process.

Within two years of the couple’s arrival, Nina left Paros, bound for Crete with one of the Taylors’ Greek friends. It was a blind-siding from which the painter sought to distract himself with paint, canvas, and alcohol.

Finally, out of the crisis with his wife, and the failure of a reconciliation attempt in Paris, Taylor seemed to find sublimation. He began to express himself in an intense, new style. Combined in that style can be seen the honing effect of Aegean light, the islanders’ mystique for discerning function through all the disguises of form, and Taylor’s own fascination with the renowned marble figurines to be found in archaic Cycladic graves.

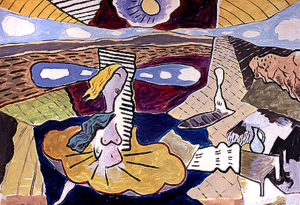

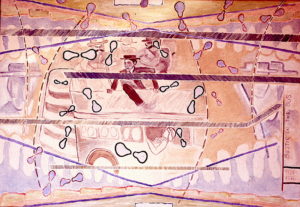

In 1967, Taylor’s response to Greek island life engendered the breakthrough painting that he’d envisioned in coming to the Mediterranean: Venus on the Half-shell. Taylor considered it a quantum-leap in his aesthetics, epitomizing the techniques, and an iconography that he would spend the next decade exploring. Venus on the Half-Shell emanates rueful humor aimed at the notion of ethereal delicacy as found in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. In contrast to the total nude innocence of Botticelli’s Venus floating to shore on a clamshell, Taylor’s Venus seems to wear the shell for a skirt. Her bare, Minoan-mother-goddess breasts entice, while the cold upraised eyebrow, and pouting lips, reject. The wind blows, and the world shifts around the love goddess, while the little man in the boat sits alone, anonymous, half in and half out of blackness.

Taylor was aware that, historically, the background for his approach to painting was established centuries before. With the rediscovery of perspective during the 15th century, artists adopted an “objective” technique for representing the world visually; one that hadn’t been employed since the time of the Romans. For the next three and a half centuries after its rebirth, the mastery of perspective, for use in representational art, was the sine qua non of artistic achievement. For many in contemporary U.S. culture it still is. It also carried the seeds of its own destruction since, ultimately, the “objective” nature of linear perspective made it photographically reproducible from the late 1800s on. Drafting skills necessary for the representational accuracy of portraits, or the manor houses of the gentry, were gradually made redundant by the camera. Taylor once remarked at a school discussion that it was no wonder that the Impressionist movement coincided with the rapid popularization of photography. Ironically, avant garde visual art ended up looking backward to validate itself against the literalistic power of the camera, back to the writings of Leon Battista Alberti, the Renaissance’s chief proponent of perspective. In his discussion of the technique, Alberti, an architect and art theoretician expressed what to his contemporaries must have seemed a quixotic reservation about linear perspective’s limitations — in that it represented its subject from only one point of view. It wasn’t until the opening of the 20th century that this particular one of Alberti’s observations was seriously considered by painters: the Cubist movement with its fracturing of space into simultaneous, multiple viewpoints.

Though Taylor vehemently rejected any attempt to classify his art, he admired Picasso, and idolized George Braque, Picasso’s alter-ego. In its own way, Venus on the Half-Shell does arrive at a Byzantine evolution of the Montmartre breakthrough of sixty years earlier. The irony is that the concepts by which Taylor worked seemed drawn from the principles of the pre-Impressionists’ old nemesis, photography. Where the Cubists unfolded and flattened at least the skin of solids into one plane, Taylor pressed the solid elements of his paintings each into its own plane in a progression of planes, often painting them so that the eye could focus on only one plane at a time. By manipulating color and tone, he sought to create non-homogenous space in the world that Picasso & Co. had flattened.

Taylor’s iconography included what he sometimes called his “paddle-men,” but which others have likened to Al Capp’s fictional creatures, the shmoos. From first coming to Greece, Taylor had been fascinated with Orthodox icons. In the silhouette and tilted head of his “Venus” it isn’t difficult to spot the special influence of icons of the Virgin.

Later, Taylor would objectify the lens-flare of a camera, using it in his paintings as either a round (bubble) or square form. Appropriating that photographic “fault,” he used it frequently to key the viewer’s attention to the transparent succession of planes — like early astronomy’s Crystalline Spheres — in his paintings. Contemplated long enough, the effect can be a sense of almost febrile distraction.

In time, his work would advance more and more deeply into the realm of hyper-perspective. Not content with fracturing elements, he would more frequently distort them, discombobulating the topography of hollow objects. by presenting simultaneously, inside and out, back and front, in an orgy of the conjunction of opposites.

But from the sly humor and elation he put into his “Venus” break-through, to the last haunted portents of Moses’ Short-cut Snapshot, the horizon, mirrored in the sky, reappears time and time again. The vantage point of these hallucinatory reflections is ambivalent, since no matter how terra-bound the setting in the foreground of a painting, the distant horizon shows curvature, like a photograph of the planet’s limb from high altitude. Between the reflected limbs, the sky seems to part on another world of blue skies and fluffy, white clouds. The doubled landscapes, above and below, each reflect every detail of the other.

The fabled “Fata Morgana” is another of these floating landscapes. This mirage, named for an ancient enchantress, has appeared in the Straits of Messina to lead ships astray since time immemorial. Sailors have regarded the Fata Morgana as a wrecker of ships. An eye-witness description includes well delineated castles and “delightful plains, with herds and flocks; and many other strange figures, all in their natural colors, and proper action…”

Perhaps it was Taylor’s fascination with the realms of the air that led him to spin the legend of his Moonwalk canvas. In 1969, an invitation to hang the commemorative painting, for an Earth Day Symposium, came from a friend in Athens. As an employee of the U.S. Information Agency, the friend had put Taylor’s painting on exhibit at the American Consulate. From there the story seems to turn apocryphal: the guest speaker at the Symposium turns out to be none other than the first human moonwalker, Neil Armstrong. As the tale goes, spotting Taylor’s canvas, the astronaut muses over the symbolic, and literal complexity of images. Finally, the alpha-spaceman’s eyes go to the signature: May, ’69, (the Eagle landed in August). “It seems that Mr. Taylor has preceded us to the Moon,” says Armstrong.

Perhaps it is a man’s fascination with the quixotic that makes him attractive to women. Soon Taylor met Stephanie Nathan, an American theater student on a side trip from Paris. She had promptly skipped out on the thespian role in Paree for that of artist’s muse. Suddenly, from the emotional bleakness mirrored in Venus on the Half-shell, Taylor’s paintings take a rebound, emanating color, and movement. He makes one of his sporadic ventures into sculpture. This is the point beyond which all vestige of Taylor’s pre-Greek perspective seems to disappear.

Through the early seventies Taylor’s paintings radiate a sexual exuberance so encompassing that it finally embodies a votive canvas to the goddess of love in Venus Reprise.

Word of things happening on Paros spread among art students looking for adventure in their education. Some were journeyman artists from Europe. Students from American colleges like Antioch were the staple, and ultimately ASFA courses were academic currency in over a hundred American universities and colleges, allowing Taylor to keep the school in session year-round. To broaden the curriculum, he offered stipends to wandering expat artists to teach other mediums. As small fry shoaled on the island, it drew bigger fish. Seeking a quiet, unpressured life, veteran artists appeared and took up residence to work day-by-day at their passions; and, in the evening eat, and perhaps get drunk in the society of their fellows. One such was Willy Hempel, a painter who had attended the pre-WW II Bauhaus and joined the Yugoslavian partisans when the Nazis closed it. Then there was Gyp Mills, a sculptor who had retired from managing the career of Donovan, a British pop star from the psychedelic era. It was rubbing elbows with the big boys, and there was more.

In its August 1972 issue on the “Aegean Islands,” National Geographic gave Taylor and his school a substantial mention. Plus, under the school’s aegis, Taylor formed Paros Chamber Ensemble, a group of American classical musicians he called his “hotshots from Boston.” The ensemble’s free-wheeling café concerts on the village waterfront, now lodged the island’s name in the minds of an increasing number of incidental tourists. Already the mayor and village dignitaries hosted an annual taverna dinner in appreciation of the school’s boosting effect on the local economy. Taylor now found himself the go-to man for newcomers, Director cum Instructor of painting, and Classical Guitar, not to mention a grab-bag of Trivium and Quadrivium seminars. The school’s eclectic approach to art included, “Taylor on Taylor” a modest introduction to himself, featuring a genealogical tree of his aesthetic descent from nineteenth century greats.

Paros in 1972 seemed to be quickly becoming the artistic Camelot that Taylor had envisioned, but at the very zenith of this golden age there was the perennial, seductive hazard of women students. Among the students of late 1971 came Gail Wetzel, a young divorcée and occupational therapist from western Pennsylvania — daughter to E.S. Wetzel, an engineer whose cousin was Jimmy Stewart, the movie star. Gail had enrolled in a painting curriculum, and when Taylor critiqued her in the studio for the first time he found himself — all six feet plus — meeting her eyes on a level gaze. Her Junoesque figure and easy good humor piqued his interest. Unaware that one day he would describe her as his raison d’être, he endeavored to keep the incipient romance incipient. At the end of her session, Wetzel packed her bags and joined with the other students on the ferry dock, for the customary stirrup-cups of ouzo.

Meanwhile, subtle friction had already begun to build up between Taylor and his actress-muse, Stephanie. In the tumultuous years between 1972–1974, she would vacate the island, his Greek friend and landlord, whom he addressed as “Papouz” (granddad) would die; and, in the U.S. his favorite grandmother would pass away, too. It must have seemed like the last straw when, Woodyard, his beloved canine companion, would disappear as well.

It was the first faintly off-key note that two years later would grow into a cacophony of “bad trips.”

During those two black years a thin thread of discontent gradually came into Taylor’s images. The exuberance with which he’d started now seemed to focus tightly on airplanes in his paintings. The theme of air travel appears in Taylor’s work like wistful sidewise glances at escape. Yet, he wasn’t his cup was overflowing where he was?

After Stephanie’s departure Taylor eventually found himself writing his former student Wetzel, and finally asked her to come and be his “co-vivant”— tongue-in-cheek euphemism he’d coined as more discrete for a school director than “mistress.” In the spring, having put her American life in mothballs, Wetzel returned to Paros. Taylor met her at the dock. On their way inland, Papouz — still alive then — shouted at them from his field wishing them, “Kaloh riziko!” (“happy, new possession”). They approached Taylor’s country house, arm in arm, up a path flapping with fanciful ship’s signal pennants painted by Taylor in his winter solitude, for that moment.

Despite its flourishing activities, by the Aegean School’s seventh year, it was chronically underfinanced. Tuition alone wasn’t enough to meet the bills. Prospects for government aid were dim. The school was incorporated in the U.S., but operating in Greece, this made it an anomaly to bureaucrats of both countries; an international orphan, a school of Lost Youths, with a “hippy” educational philosophy.

With Wetzel’s assistance in administration, Taylor, the artist, was able to devote more energy to private fund-raising. Though the Director loved entertaining friends, he chaffed at the increasing loss of painting time. There were personal friends, businessmen, alumni, and vacationing academics encountered strolling the waterfront. No stone was left unturned. There were too many relationships; too many tainted by the indignity of fund-raising. It was an activity best done over a few drinks.

In periods of faith he spoke of finding an “angel”— a wealthy patron a la theatre jargon — who would recognize the school’s revolutionary potential, and in exchange for a footnote in art history, richly endow the not-for-profit organization. The day after attending one of Taylor’s potential-angel dinner parties, a friend joked that if the fund-raiser had to keep on drinking at that rate, he would never see forty.

In the summer of 1974, Greece’s banks were closed and armed Greek soldiers appeared in the streets of Paros’ main village, Paroikia. For Taylor, as well as Greece, it was the end of an era. He would later reveal the dilemma that dogged him during the crisis of Greek-Turkish saber rattling: If the Turks came, should he fight along with his Greek neighbors, or evacuate to the U.S.?

Ultimately, the Greek military junta resigned and the decision was never necessary. But perhaps, having posed the question to himself, it wouldn’t go away. That fall, on a fancy, the school’s Creative Writing instructor brought back sabers and fencing masks from a trip to Athens. Already at crossed swords with his new teacher over academic questions, Taylor took up the challenge, welcoming a possible winter’s entertainment as well as a chance to pursue their philosophical differences by means of a “conversation in steel.” Both men were highly competitive, and lacking a qualified fencing instructor, they undertook to teach each other lessons from a D.I.Y. book entitled, Fencing. Ripped clothing, red welts, and split knuckles — trial by ordeal was the order of the age. Still, while the fight-or-flight question with which Taylor thumb-wrestled, was more Byronic than existential, his struggles would soon take place on less elevated ground. Following the junta, came a civil government with economic development and Common Market prosperity in mind.

And, for a while, Taylor’s fortunes seemed to be looking up too, from an inheritance that came to Wetzel. Seeing the means to distract her companion from school/money worries, she gave him the windfall to buy a seventeen-foot sailboat Taylor had seen advertised in an English language newspaper in Athens. After eight years, Taylor’s manner was now as much Greek as American. If there remained any ambivalence about where his life would be spent, committing to a boat must have been second only to a house in burying it.

Within days, he’d picked up the little sloop, registered it as Corinne — Wetzel’s middle name — and with the help of his dueling partner, island-hopped from Marathon on the mainland, to Paros. For four days, the two erstwhile competitors careened from Kea, where they sheltered for a day; to Syros, to Paros, all in gale force winds. The wildness of the voyage permanently bonded the two men and etched itself deeply into Taylor’s imagination.

He had always loved boats and water. In truth, the voyage of the Corinne was a case of reality imitating art. Beginning in 1974, the year before the voyage, Taylor had begun painting a group of five sun-bleached canvases exploring the permutations of sun and sea and sail. A most remarkable thing about these pieces is the quasi-mechanical precision of drafting, and their progressive loss of color. Coming from the brush of one whose articles of faith were “spontaneity” and “color,” there seems an uncharacteristic struggle for control on Taylor’s canvases. The last of these — not a sailing picture — was Buster on the Bus, wherein the eponymous figure is as faded as an image from a silent, Buster Keaton film. The scene is the interior of a bus full of Greeks. The exhausted colors of the painting are ethereal, like the vision of an oxygen-starved brain. Toward the back of the bus, the figure of dead-pan comedian, Keaton, struggles forward by climbing over the backs of the other passengers’ seats.

But interpretations of art are subjective, and the apparent loss of color/affect in his paintings might also have represented a visual analogue to Taylor’s new musical enthusiasm. He’d propped his guitar in the corner of his studio. In its place, he tried to take up the Cool-School saxophone à la Coltrane. Somewhere, in the midst of the “coolest” color temperatures — and, by his own standards the most over-controlled painting he would ever do — bit by bit, the sky began to fall.

Between 1974 and 1979, Paros’ growing popularity with the café-chic, Club Med types, and assorted other jetsetters sent the cost of living steadily higher. Struggle as he might to keep up with the island’s new, tourist-inflamed economy, the dream in which Taylor had tried to envelope himself seemed constantly on the point of drying up and blowing away. He made a barn-storming effort to sell Aegean School franchises. From 1974–1977, the Aegean School of Cultural Anthropology as well as the School of Classical Studies and Philosophy held summer sessions on the neighboring island of Naxos.

But ultimately the infant mortality rate of Brett’s attempts at midwifery was one hundred percent. It was surely a lasting wound to one who set great store by creativity. He would lose the school building when it dawned on his landlord that tourist rooms paid better than studio space and photo-labs. No sooner had Taylor resituated ASFA in a smaller, Venetian-era building, than his friend in the American Consulate, who had been active in searching for school funds, died.

By the late Seventies, Taylor would lose even his dwelling of ten years. The farmhouse where he’d had his “perfect” studio had been the property of Papouz. On the old man’s death, Brett was invited, summarily, to vacate the premises, as the house was needed for Papouz’s son’s family. Though Taylor forever protested that this violated an understanding between himself and the old man, it was like trying to squirt water up a rope. The days of reasonable rents had passed, and trying to maintain the school while buying a house threatened to throw Taylor and Wetzel into a financial tail spin. A crisis was averted when Wetzel and Brett’s mother managed buy a small house on the village’s ancient castro fortifications. A short time thereafter, Papouz’s son built his family a modern house and rented the old farmhouse out to vacationers.

Taylor, the Founder/Director of the Aegean School of Fine Arts, never forgot the sting of dispossession he felt. As a member of a community he had considered “home,” he had been left “out to dry.” Taylor struck back with a bit of psycho-drama worthy of a John Fowles novel.

It was a dark and rainy winter night. The hundred meters of village market-street was lit by two or three fifty-watt bulbs. Occasional persons appeared on the street; then disappeared again, indoors. Taylor and a co-conspirator had dressed in dark overcoats with deep hoods that hid their faces. Using a discarded stretcher from the village dump, the two carried the last loads from Taylor’s old house, covered with a blanket. Each load had been artfully arranged to look like a body. On the third trip, an older woman had opened a second story window and asked who the two stretcher bearers were carrying. It was the moment that Taylor had been waiting for, and he responded in a sepulchral voice with the name of the evicting landlord. The woman had crossed herself and drawn her shutters back together. Within days, a tale of faceless monks carrying a body through town on a stretcher was all over the village.

Perhaps Taylor’s dispossession shattered some illusion about his standing with the islanders. By spring, he complained to Wetzel that “physically” something was wrong with him. And was there a yellowish cast to his eyes lately? A visit to the village doctor set Taylor off to the U.S. for blood tests.

Nothing definitive could be determined in the time Taylor could leave the school, but he returned, confiding to his co-vivant, that for health’s sake, he might have to cut down on the alcohol.

By the time of his interview with the Dominion Post in April of 1979, an ominous fatalism had crept into Taylor’s normal obliqueness in public relation matters. At the end of describing his expatriate life as an artist-cum-director, he concluded:

“It’s not a comfortable life. We don’t have any salaries. We just take enough to pay our rent and food. And by the time you get to your mid-thirties, you begin to wonder what would happen if you got sick, or suddenly had to fly to the states, and you had no insurance, and only a hundred dollars in your pocket,” then stoutly, “…but I chose it.”

For the last three years of the seventies, he managed a number of oriental-format, brush drawings on paper. Also, harkening back to his days as a printmaking instructor, he created two etchings.

At this point, those around Taylor attributed his growing gauntness to nothing more than a reflection of his four-year artistic drought. He seemed simply to have no physical reserves to burn, even on painting. Then, three years before his fortieth birthday, something in the artist spontaneously ignited. The first burst of that inner conflagration was Fred Reefing. He’d done nothing like it since before the muted washes of his “Cool School” period. The work now blazed forth with the vivid, intuitive palette of a preschooler. The artist’s vantage point had come down to Earth. The bow of the horizon is still there, but there is no tantalizing mirage, no Fata Morgana.

In real life, the voyage depicted in Reefing was an expedition to the neighboring island of Siphnos with his friend, Fred Remington III, Fred’s wife, Jenny, and three seasick students from the art school. The canvas depicts the boisterous state of affairs as the Remington’s sloop, Syrinx, comes into the wide-open fetch between islands. The couple’s utter exhilaration, and the wretchedness of the three students, encompasses both the joy and pain of existence. Technically, Taylor once again adapts photographic conventions, indicating that the students are below deck by use of the classic, film, remote-view bubbles.

Compared to the nearly obsessive multiplicity of his studied avant garde paintings, Reefing is as straightforward and sanguine as a dog chasing a ball. There is a burning urgency and a willingness to let aesthetic principles fall where they may. Yet, in the midst of all this joie de vivre, one senses a dark undercurrent. In one of only two known self-portraits from the Aegean years, Taylor paints himself at the tiller, setting the course. Reefing is clearly his voyage. He faces away from the viewer, shoulders slightly hunched revealing less profile than a one-eyed Jack. Those who knew Taylor then, will verify the visor and glasses and moustache. But like the little man in Venus on the Half-shell, thirteen years earlier, the artist sits in the boat’s stern. He seems to stare past the scene of human endeavors, across the endless sea ahead, searching perhaps, for a glimpse of the fabled realm of earlier days.

Summer of the new decade, Taylor and Wetzel traveled together to the U.S. Savoring the now almost foreign home-life, they side-tripped to see a brother-in-law run the Boston Marathon. Taylor followed up on his previous medical visit remarking afterward that his new doctor was a “teeny-bopper.”

Later, back in Greece, he’d discovered his co-vivant’s concealed desire to have children. Only at the approach of her forties had she inadvertently revealed her longing to Taylor’s mother. In Wetzel’s mind, the dead-line was forty-one. Whatever Mykia Taylor said to her son, he ruminated upon it; then, gathered himself up like an exuberant warrior flying to the front. A year later, whether from health problems, or just the throw of the dice, nothing had happened.

Placed side by side, the last three paintings that Brett Taylor completed compose a triptych confrontation of his own mortality. If Reefing had contemplated eternity, then Summer Optics meditated upon disengagement:

Summer hydro-foil service had come to the island in 1981. To many islanders, this supersonic transport of marine travel represented a giant step into the light of modernity. Yet, Summer Optics’ dark atmosphere and unbalanced, snap-shot composition seems more to reflect a disconsolate contemplation of the prospects. The ghostly, haunting images of old-time village life appear submerged beneath the wake of the phallic hydrofoil. Perhaps there, submerged like Atlantis, may be found the missing Fata Morgana. In a caricature of photographic time-exposures, Taylor uses his signature “icons” to represent both a long wail, lingering in the mind’s ear, and a photo-smear left by the hydro-foil’s ports, and running lights.

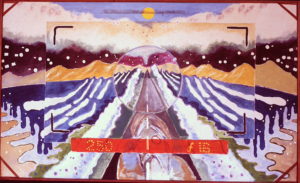

Though Moses’ Shortcut Snap-shot was the last painting that Taylor did, it could be nothing but the center image of his triptych. In contrast to either Reefing or Optics, the artist has laid out Shortcut with a near, bipolar symmetry. So static a composition wasn’t his usual way, yet, with it, he succeeds in creating a monumental stasis; an instant frozen full of impending forces: the glaring force of its saturated colors, and sheer cliffs of Red Sea water, poised to inundate all. And out of the Fata Morgana the elements come together into some looming, cloud-headed Yahweh, intent on swallowing Moses. The prophet trudges, washed-out and dismayed, insubstantial as a ghost, across the seabed.

Here, as never before, Taylor captions his painting, cryptically, in the language of f-stop, and shutter speed displayed in red before Moses’ eyes. Photographically, the numbers tell of clarity: light which reveals both near and far; clarity in which no host of Israelites crowds behind; and beyond that, up the white-lined highway, barely visible figures suggest pursuit.

Taylor finished Shortcut in the fourth quarter of his thirty-ninth year. In an unfinished poem from the same era, he writes:

“…He wants a sign.

He wants the sky to open…

He wants to see a burning bush,

With its voice of God on fire.

Let the soft clouds go brittle, and shatter.

Let the sea part…”

In the winter of 1982–83, the sky truly fell. Both Wetzel and Taylor’s health took nose-dives. First one, then the other, made emergency medical trips back to the U.S. Finally, in the spring of 1983 both of them ended up in Brigham and Women’s hospital, on different floors. They would never see Paros again together. Wetzel was soon on her way to recovery. For Taylor there was no such luck. On April 12th, at the beginning of his fortieth year the artist died from his long-deteriorating health. He’d heard of his co-vivant’s recovery before he died, and in a final Jay Gatsby flourish, sent a bottle of champagne to her room on the floor above him accompanied by a card: “Am in a state of utter relief….”

In June of 1983, against the backdrop of the Aegean School’s struggle to survive with new owners, Gail Wetzel returned from the U.S. bearing a small, plastic-lined box containing Taylor’s ashes. Honoring her co-vivant’s wishes, she met Taylor’s quondam fencing partner quietly at the south end of Paroikia village. From there they carried an inflatable dingy called Guernica along the shore to the pebbly beach of a small bay where they pumped it up. Paddling out to where the water went from turquoise to lapis, they emptied Taylor’s ashes into the Aegean.

Into which rank Taylor’s art will eventually find its way, is the province of time and the work’s appeal to the human heart. The technical innovations are more easily discerned. Since Manet’s Fifer, traditional-medium painting has been on the defensive against the camera. While his Aegean work reflects its debts to the Cubists, forty years its senior, Taylor, a lover of irony, diddled with both photographic format and theory, then did before the camera what no camera can do — psychic snapshots intended not to evoke another’s subjective “take” but communicate an objective emotional experience. Freed of native expectations, Taylor’s entire Aegean oeuvre contains the hybrid vigor of expatriate sensibilities, with their strange, half-recognizable fragments of the sixties.

The question is not whether Brett Taylor was a hero or a fool. In that realm of concern, he left the legacy of his art and The Aegean School of Fine Arts. And he was willing, however perverse the will, to live the artist’s life as he conceived it, with all its occupational hazards, to chase the Fata Morgana to the inevitable end.