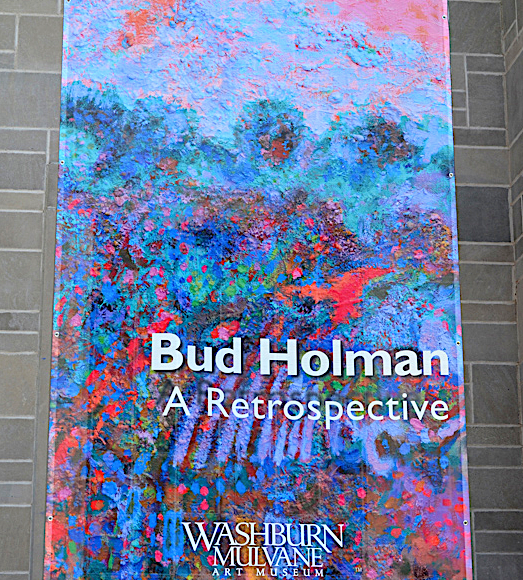

Master of the Lyrical Expressionist Landscape

How does one determine whether or not a painting style is distinctly inimitable rather than one that is constantly striving to become a style? What makes it truly innovative rather than derivative?

For Bud Holman, the proof lies in examining not only the originality and flair of his unique style but showing how he tapped and ultimately transformed those inspirational sources in creating his own brand of lyrical expressionist landscape painting.

Understanding the authenticity of Holman’s art begins with the simple edict by which he has lived and painted: “Know thyself.” Fulfilling that mandate can be burdensome for a young artist of any period but it was particularly difficult in New York during the post-war years when Abstract Expressionism had exploded on the scene, making New York the epicenter of the art world. It was a time when other movements were swirling about, from Neo Dada to Pop to Post Modern. Holman found many colleagues throughout this diverse avant-garde period, but he followed a different path than his closest artists — Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Willem de Kooning, and Alfred Jensen among them — who have long been ensconced in the pantheon of American masters.

This story reveals the life and works of a reclusive and prolific master. In his mature body of works one delights in discovering a voice that is truly original — and distinctly American — in the history of contemporary landscape painting. It’s a voice that captures the true spirit of reverence for the land in all its atmospheric moments.

COULDN’T BE MORE AMERICAN

Holman was born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1926. “I’m from Kansas — the heart of America — raised in an old Kansas family,” he proudly claims. Despite his deep knowledge of many cultures throughout history, as well as his extensive travels to many countries, he says, “My paintings are not international. I am squarely American, from Topeka, Kansas. My paintings couldn’t be more American.”

The starting point of Holman’s path — one that would keep him out of the limelight — is attributed, in part, to his upbringing in the Presbyterian church. His ancestors were abolitionists from Vermont and New Hampshire. They established the church in Topeka during the turmoil of the Civil War era in a period of territorial expansion that often turned violent, bestowing upon the state the nickname of “bleeding Kansas.” Holman’s parents impressed upon the young boy the Presbyterian ethos, which stressed the merits of being disciplined and frugal but also showing generosity and hospitality to others. Working hard on one’s own and not taking advantage of others was underscored in these principles. Every day, young Bud Holman rode his horse “Tony” to a one-room schoolhouse. These family tenets would later play significant roles in Holman’s decisions as an artist.

Growing up in Kansas during the 1930s also meant experiencing the extended period of drought that had made the Great Plains so arid that it became known as the Dust Bowl. Many farmers fled the plains seeking employment elsewhere. Most were drawn to California but often wound up in large camps of migrant workers.

One of the keys to understanding Holman’s paintings is that three disciplines — painting, art history, and archaeology — would endure as central passions throughout his life. As a boy, he had always held a fascination for Native American culture and had heard stories about the long-lost Pre-Columbian city of Etzanoa [Cibolia] in Kansas, only recently confirmed.1 In regularly scouring the Kansas farmlands he formed a large collection of arrowheads and artifacts — a collection that throughout his life was displayed in his various studios.

During the summers his parents continued to educate their sons, Bud and Calvin, by driving to every region of the United States. They even traveled throughout Mexico, where the architecture and monuments of the great Aztec culture enthralled the boys and instilled in them an appreciation of both history and the landscape. Bud was always sketching on these trips.

The American painters of the Western landscape who impressed him most were Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt. The majesty and drama of their huge canvases had enthralled the 19th century public. Of even greater influence upon Holman were the paintings of Albert Pinkham Ryder, the reclusive American painter who imparted poetic mood and mystery in his landscapes. Photographs of his paintings were always tacked on the walls of Holman’s studios. “My paintings really come from the spirit of Albert Pinkham Ryder and Thomas Moran’s exuberance for the landscape of the Old West,” he said.

Holman received his first formal lessons in painting from Marion Kavenaugh Wachtel when he was a young teenager visiting relatives near Pasadena. She was one of the leading women landscape painters in California, and from her he learned not only technique but was impressed with her dramatic viewpoints that expressed a love of the Southwest landscape.

THE ARTIST AS ARCHAEOLOGIST

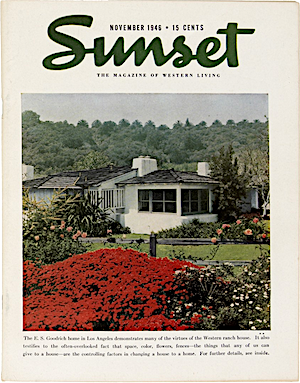

By the time Holman entered Stanford University during World War II, several lasting influences determined that he would pursue fine art, art history, and archaeology. In 1946, while he was a sophomore, he showed his drawings to Walter Doty, the editor of Sunset — a magazine that has long played a significant role in attracting Easterners to the culture and landscape of the West. Recognizing Holman’s talent, Doty commissioned him to travel to Mexico during the next two summer breaks making drawings of landscapes, gardens, and flower markets. After World War II Mexico was experiencing an explosion of tourism, and these drawings were used to illustrate articles in the magazine.

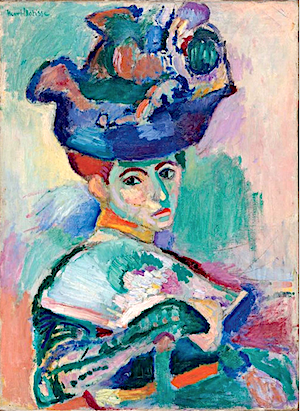

Archaeology exerted its pull when Dr. Hazel D. Hansen, head of the university’s Classics department, got Holman interested in piecing together the thousands of fragments that had formed the Cesnola Collection of ancient Greek pottery and artifacts, all of which had shattered during the 1906 earthquake and stored in the museum ever since. Art history came to life when the head of the department took Holman and several other students to the home of Sarah Stein, the wife of Gertrude Stein’s brother, Michael. In 1935, after three decades of living in Paris and collecting the art of the avant-garde, the Steins had moved from Paris to Palo Alto and were planning on donating much of their collection to the university. Sarah took a special liking to Holman and often invited him for tea in her garden while they discussed a range of art topics. As that relationship deepened, Holman’s exposure to the Stein’s formidable collection of early 20th century avant-garde French masterpieces proved a critical point in his artistic development. “The Stein’s home was wall-to-wall with Matisses, Cézannes, Braques, and Picassos,” he recalled. “One day in their living room, my gaze fell upon Woman in a Hat, Matisse’s seminal 1905 portrait of the woman with the green stripe down her nose.” It was the very painting that in 1906 had caused critics to derisively call Matisse and his colleagues “Les Fauves” (the wild beasts). Many artists have credited the paintings of these early modernist masters for having opened their eyes to new ways of seeing. Holman’s intimate exposure to the Stein’s large collection proved to be a powerful catalyst that would launch him on paths of deeper explorations that led from the Fauves to the School of Paris to the Abstract Expressionists of New York, and then to a style his own.

Holman’s exploration of painting, art history, and archaeology continued in graduate school at Stanford. As a boy he had been fascinated by the petroglyphs carved into cave walls by the ancient Native Americans of the Southwest. When, in 1948, the discovery of the 17,000-year-old Lascaux cave complex was opened to the public, it reconfirmed for Holman that mankind’s psyche has always been sparked by a primal desire for visual expression, not only to document events and communicate beliefs but to make spiritual declarations. Holman was so inspired that he began collecting art objects from the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures. “I found that the Western art world first began in Mesopotamian culture,” he said. “People paid for paintings, pottery, and tablets they considered of value.” He added to his collection a 5,000-year old painted wooden fragment from a mummy’s sarcophagus bearing a face, which has remained an inspiration.

EXPLORATION

After receiving his Masters degree in 1950, and then steeped in three disciplines, Holman traveled extensively. He returned to Central America before launching to the Mediterranean basin. He also explored of all its coastal countries — including Turkey, Greece, Israel, and Morocco — becoming directly familiar with their ancient architecture and temple plans. In Istanbul, he met Paul Underwood, the director of the Dumbarton Oaks Museum in Washington, D.C. This research institution remains known for its expertise on three of Holman’s favorite subjects: Byzantine art, Pre-Columbian studies, and garden and landscape design. Noting Holman’s enthusiasm, knowledge, and artistic vision, Underwood offered him a job to work for Dumbarton Oaks. Also, after seeing Holman’s works, he was confident that Holman could have a successful career as an artist.

Holman chose the route of the artist, settling into an apartment in Florence on the piazza overlooking the iconic Duomo designed by Brunelleschi. There he soon met Aldo Gucci, who asked him to model his jewelry for the famous fashion house. While this was an enjoyable diversion, Holman felt, like many American artists before him who made the pilgrimage to Florence, a stronger pull from the Gothic and Renaissance masters. He was particularly impressed with the architects of the many medieval churches of Northern Italy, because many exaggerated the width of their flat façades by cutting black stones to serve as long horizontal stripes in contrast to the larger areas of lighter-colored stones.

Holman observed that the Renaissance architect Alberti pushed the impact of the dark stripes to its peak in the Santa Maria Novella. The Florentine architect created a grid of geometric shapes whose black and white banding has the deceptive power perception of the flat façade. He also noted the trompe-l’oeil effect of activating a flat surface in the extraordinary interior of the Orvieto Cathedral. Its black and white horizontal stripes are dramatic counterparts to the diaphanous light filtering from its thin alabaster window panes. The stained glass windows of other cathedrals impressed upon him the work of Georges Rouault [French, 1871–1958], whose colors were made more brilliant by signature black outlines. This effect of flattening the picture plane as if it were stained glass, a cathedral façade, or a mosaic would later be found in Holman’s expressionist landscapes.

THE VIBRANT 50S IN NEW YORK

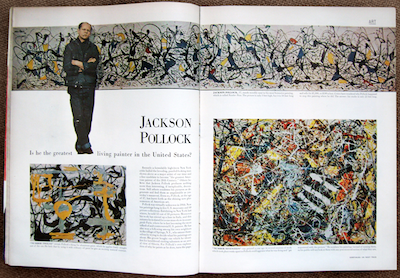

It’s important to note that Holman’s most formative years as an artist took place during World War II. When he was in college the allied forces had reduced Munich, Berlin, and Dusseldorf to rubble. Paris was free to resume its position as the capital of the art world. Before the war, the intelligentsia and the cultured set like Gertrude and Sarah Stein were collecting the French Impressionists and the early modernists such as Matisse and Picasso. In 1949, when Holman was in graduate school, the August issue of LIFE magazine changed everything. It featured a 2-page spread showing the irascible Jackson Pollock in front of one of his big drip-action paintings. The headline read: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” That provocative headline was also interpreted as mocking. In fact, the article elicited more letters than any other article LIFE received that year — and most of them were derisive. The public simply could not comprehend why Pollock was getting one or two thousand dollars for paintings that, as the old saw goes, “even my kid could paint.” But the LIFE magazine article changed all that. It announced Pollock as the great disruptor and intrigued a new generation of collectors. No sooner had Paris been freed of the Nazis than the Abstract Expressionists won another war: New York had displaced Paris as the epicenter of the art world.

After Holman’s extended sojourns in Europe he returned in 1954, settling into an apartment in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village at 40 Commerce Street. The neighborhood was lined with charming early 19th century townhouses. His studio — which was situated above the famous Cherry Lane Theatre (a playhouse founded by Edna St. Vincent Millay) — afforded a huge skylight that flooded the rooms.

He had arrived in New York with the advantage of parents who were culturally connected in Kansas. Holman’s father and namesake, Charles Edward Holman, was a successful entrepreneur and owned the Yellow Cab Company based in Topeka. During the early 1930s Charles was the first to install short- wave radios in his taxi fleets, thereby giving them an advantage in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska. Only later did police cars widely adopt this means of communication. Charles later became the head of the Topeka Savings & Loan Bank. Now, his son nicknamed “Bud” landed a job at the Museum of Modern Art. He was in luck because that June MoMA opened its Shofuso Japanese House and Garden to the public and assigned him to manage it until the exhibit was closed in the Fall of 1955. 2 He also managed MoMA’s Guest House at nearby 52nd Street — now a historic landmark — designed by Philip Johnson in 1950 and donated by Rockefeller. “The Guest House became a showplace for MoMA,” Holman recalled, “and was like an extension of the museum for private parties.”

Holman quickly assimilated into New York’s art world during the vibrant 1950s. He met many of the artists of the avant-garde who had found exposure through the annual Ninth Street Exhibition. Leo Castelli originally curated that series, which had started in 1951 as a pop-up for overlooked artists and ran through 1957. 3 Holman also met his friends at those two social meccas of the avant-garde — Max’s Kansas City and the Cedar Tavern — which were not far from his studio. However, he says, “I was not an adventurous and loose creature in this bohemian society.” He knew Jackson Pollock but did not particularly care for his coarse manner, noting that he found the Cedar Tavern hangout to be “a rough, smelly, vomitty place, with Pollock hanging all over bimbos.”

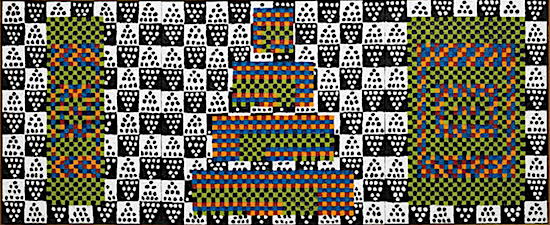

Another of Holman’s close friends who pursued a very different artistic path was Alfred Jensen. Holman immediately understood that Jensen’s diagrammatic and checkerboard compositions not only explored color relationships but were also inspired by subjects of which Holman possessed his own considerable knowledge: Greek temple plans and Mayan culture and its calendar.

Through his job at MoMA and his growing network of artist friends Holman met the three leading women who owned major galleries as well as many of the artists they represented. Edith Halpert, owner of the Downtown Gallery, was a legendary pioneer dealer in American modernism and knew the Holman family in Kansas. Holman also knew Eleanor Ward, owner of the Stable Gallery, who represented de Kooning, Kline, Motherwell, Pollock, and others. He even bought paintings from Ward, including a few by his friend Twombly from his 1957 solo exhibition at Stable. His relationship with Bertha Shaeffer, owner of her eponymous gallery, was multi-faceted. She represented Rauschenberg, Johns, and began showing Holman’s work regularly in her group shows. In 1956, thanks to Holman, his friend Alfred Jensen was given a solo exhibition at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery. The next year Schaefer asked Holman to join her gallery as a director.

When Twombly married the Italian baroness Luisa Tatiana Franchetti, an accomplished painter of high society portraits, Holman hosted a going-away party for Twombly’s last night in New York. The couple had purchased an apartment in Rome near the Spanish Steps in a 17th century palazzo built for the Borgia family. Photographs of them in their spacious rooms were shot by Horst P. Horst and illustrated in Vogue in the mid 1960s. “I’m not clever. Cy was clever,” commented Holman. “Cy worked his way into a high society nest when he married the baroness.” Twombly’s good fortune was topped off by the fact that the baroness’s brother was a prominent art collector. He also owned La Tortuga Gallery, ensconced in his enormous palazzo, where he exhibited Twombly’s paintings.

By 1959 Holman’s interest in Bertha Schaffer’s gallery had waned and he was eager for a new challenge. A friend who worked at the architectural firm of Skidmore Owens and Merrill alerted him that David Rockefeller was looking for a curator to build an art collection that would be exhibited throughout his new 60-story headquarters on Wall Street for Chase Manhattan Bank. Holman secured the job and for the next three years worked directly with Rockefeller, assembling a huge art collection. He often purchased directly from his friends’ studios — from DeKooning to Rauschenberg. Chase Bank has ever since been lauded as the pioneer corporation for collecting contemporary art.

David Rockefeller often expressed his gratitude to Holman for his curatorial role in building the collection during a three-year period. Since Rockefeller knew that Holman was eager to return to painting, for the next three years he would periodically send him friendly letters asking about his art and stressing that he was ready at any time to help promote his career. It would be one of several major opportunities of which Holman would never take advantage. “It’s a great regret that I never replied to those letters. But I was taught that you have to make your way on your own terms. I was determined to make my own success with painting. I had an absolute stubbornness to be untainted.”

While never an opportunist, Holman possessed character traits and sophistication that allowed him to easily navigate all social networks, including parties held within New York’s high society. In addition to being described as classically handsome, he was highly educated, cultured, and good-natured. After Towmbly left for Italy Holman became to close to Philip Johnson andDavid Whitney — the latter a proponent of lyrical abstraction. “David was crazy about my paintings and really encouraged me,” the artist recalled. Despite Whitney opening his eponymous gallery in 1969, Holman never actively promoting his paintings in New York. “So, now when I look back, I see I’ve wound up in an edgy place, tasting the bitter thing that I’ve caused myself.”

Holman always followed his wanderlust for new inspiration. Intrigued by the arts of Morocco, from 1961 onward he made at least twenty trips there working as a designer of luxury carpets and rugs for Edward Fields Carpet Makers. (Fields is credited for having coined the term, “area rug.”) Inspired by Morocco’s craftsmen, Holman also created rug designs for Talbot’s. His friendships in the industry grew, including that with fabric designer Eddie Bragolin, who often invited Greta Garbo to his expansive apartment for dinner. Holman recalled one evening when Garbo expressed her adulation for Bragolin’s collection of paintings by Nicolas de Stael [1914–1955].

Holman had also admired de Stael’s expressionist works because they were infused with a vocabulary of shapes and colors that poetically yielded an implied landscape yet remained essentially non-objective. Another friend in the design world was the textile manufacturer Werner Abegg, whose collection of ancient textiles is housed in his eponymous museum near Bern, Switzerland. The design business kept Holman traveling extensively from the early 1960s until 1974 but he kept painting wherever he went. “The three countries that have had the most impact on me in terms of color are Turkey, Egypt, and Morocco,” he says. “I was heavily influenced by the swirl of action, the vibrant sense of color and color combinations, the patterns of tiles, and the exotic dress of the local people.”

Looking back at the 1960s, one sees a decade that was as tumultuous as the 1950s, when even the Abstract Expressionists — those great disruptors — were in turn upset. It was a decade of seismic consequences. The art world exploded with a succession of new and disparate movements ranging from Pop Art to Hard Edge and from Minimalism to Op Art. Each was an overlapping assault reacting against, or morphing from, Abstract Expressionism.

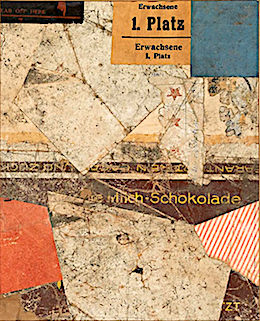

Collage was part of that assault, and Holman dove in. The work of one of the earliest masters of collage, Kurt Schwitters [German, 1887–1948], inspired him to explore that medium. Plus, in 1961 MoMA mounted an exhibition, “The Art of Assemblage,” which featured a range of masters from Braque and Picasso — and it included Holman’s friend Rauschenberg, who was pushing collage deeper into three dimensions as assemblages. Holman created a series of what he calls “painted constructions,”wherein, like an archaeologist, he used paint to “embalm” bits of cinder rock, rope, wood, toothpicks, nails, spoons, and gravel. “I sat on the floor and worked on these for years,” he said — which explains why he later dated many of them 1964.5

A UNIQUE STYLE MATURES IN NEW MEXICO

From the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s Holman had thoroughly studied and absorbed the histories and cultures of the Americas, as well as those of the Mediterranean basin — from ancient times to present day. When he emerged on the contemporary scene, he was a peer of the artists of the New York School, and not all of them were purely non-objective expressionists. Figurative expressionism and lyrical landscape expressionism were vital movements even though they did not make LIFE magazine.

Some of Holman’s good friends, like John Grillo [1917–2014], Angelo Ippolito [1922–2002], and Nicholas Marsicano [1908–1991], also took the lyrical approach to producing expressionist landscapes and figures. Despite exhibitions that brought them respect as accomplished painters, they found their greater reward not in gallery exhibitions but in dedicating themselves to a profession that offered greater security: teaching. Ippolito and Marsicano taught at Cooper Union, and Grillo taught at the New School for Social Research. At the same time, Holman found an affinity with some of the artists of his generation from the School of Paris. The best-known of the lyrical expressionists among them — and with whom his paintings relate — were Jean Fautrier, Serge Poliakoff, and Nicolas de Staël.

However, by the early 1970s Holman felt increasingly compelled to make a major change. He instinctively sensed that a return to his roots in the West and full immersion in that environment would allow his still-evolving painting style to reach its full maturation. That opportunity came in 1974 when his father provided both encouragement and support. Together they purchased and restored a 250-year-old adobe hacienda on Canyon Road in Santa Fe. The painter’s instincts proved correct and his bond to the landscape and its native peoples proved equally intense and enduring. He visited all 18 of the pueblos along the Rio Grande, becoming even more familiar with the customs of the Apache, Navajo, and Zuni. Observing so many of their dances and rituals brought him an even greater understanding of Native American culture and its profound respect for the distinctive landscape of the Southwest.

Fifty years earlier, the first modernists were drawn to New Mexico by the freedom presented by its vast expanses under majestic skies and surrounded by dramatic geological formations. Some of the great American modernist landscape painters who had earlier spent time in Santa Fe were Marsden Hartley [1877–1943] and John Marin [1870–1953], who made visits around 1930 before eventually settling on the coast of Maine. Another was John Sloan [1871–1951], who was a Santa Fe resident for at least four months of every year from 1919 until his passing. Painters like Lawren Harris [1885–1970], a member of The Canadian Seven, lived in Santa Fe from 1939–40. He was a founder of the Transcendental Group of Painters, who believed that art should be an authentic expression of the spirit. Georgia O’Keeffe made many visits and eventually was compelled to stay, settling at Ghost Ranch.

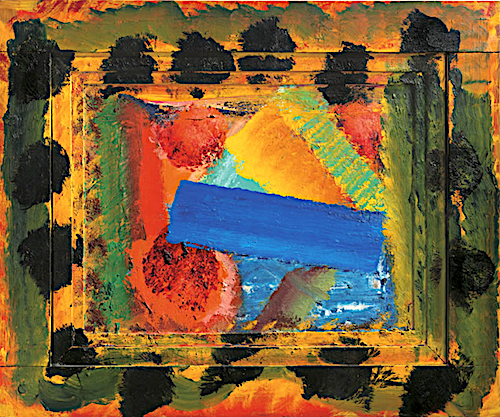

Holman was equally compelled, and he wound up creating an expressionist style that is unique among American landscape painters. He acknowledges as his first debt of inspiration the great amount of time he spent as a young man absorbing the masterpieces in Sarah Stein’s extensive collection of Fauvist paintings. In that moment he knew that his paintings could take a path that could express much more than the illusion of reality and depth. Confirmation came from his exposure to Italy’s great Gothic and Renaissance churches, which inspired him to deepen his understanding of how shapes and stripes could incite movement on a flat picture plane. These experiences, including his role among the avant-garde in New York and Europe, ignited his vision, reducing his compositions to simplified, schematic designs that yielded even greater flatness of space. All the while, his canvases burst with the energy of color while his boldly brushed shapes maintained the vocabulary of earth, trees, and sky — all merging together like the monumental and layered façades of a great Italian cathedral or a Medieval tapestry. He would never follow the easy path of realism commonly found in contemporary art of the West. Indeed, his paintings stand in direct contrast to those produced by many painters of the Southwest who have been seduced to illustrate the “big sky.” Such works subdue the role of the land in relation to the vast expanses. Holman instead asserts the mountains and hillsides for the leading role in his landscapes. The energy he finds in their great mass is reflected by a myriad of colors applied with bravura brushwork that invite us to delight in the greens, turquoises, and blues among the yellow ochres and burnt umbers of the arid soil and rocks. Being occupied in exploring this plane of activity dissuades us from searching for the depth in the actual scene that stood before him. Meanwhile, Holman often employs sparks of oranges and reds — which may be shacks in the hills — recalling the drama of the Fauves from whom he learned to use color and shape to control the structure of the patterns of the picture plane. In this way he captures movement in space, light, and color dancing across the surface. Finally, the eye finds a relief from all of this vibrant activity in the high horizon bands that crown his landscapes. They inevitably draw the eye up to them rather than allowing it to search for a path that would lead deep into the scene. After so much visual excitement they are like a pressure valve, releasing us to the sky. This is how Holman’s compositions, sparked by his color palette, resonate and play to our subconscious.

Owing to the authenticity of his spiritual grasp of the land, Holman’s elegant work celebrates nature’s landforms to monumental effect. His approach is different from that of the Fauves, who emerged during the first decade of the 20th century with bright colors that were criticized as garish and beastly. In landscape, their paragon of color was the red rocks of the Côte d’Azur, and to varying degrees they and their de facto leader, Matisse, gradually replaced pictorial depth with the shapes of the flat plane. However, Holman’s expressionist approach, which dramatically flattens the structure of the landscape, is rare among the works of the best-known Fauves such as Matisse, André Derain, Jean-Baptiste Guillaumin, Maurice de Vlaminck, Henri Manguin, and Albert Marquet. Landscapes punctuated with a high horizon band, like Holman’s, are very rare in that group. It appears that even Matisse created only a few like this, painted during the breakout summers of 1905–06.

Ultimately, Holman stands out as an expressionist who captured in his landscapes the rhythms of nature. While he admired a number of painters, three stand out as his brothers in spirit. Howard Hodgkin [1932–2017] was a British peer whose abstract landscapes are often composed of punches of brushwork combined with rectangles of color. At first the whole appears to be completely non-objective but closer contemplation reveals the poetry he felt in the landscape. Plus, his titles often refer to specific places and subjects. Hodgkin once explained, “My pictures are finished when the subject comes back. I start out with the subject and naturally I have to remember first of all what it looked like, but it would also perhaps contain a great deal of feeling and sentiment. All of that has got to be somehow transmuted, transformed or made, into a physical object… when that’s finally been done… and the subject comes back… then the picture’s finished.”6

Chaim Soutine [Russian–French, 1893–1943] was another expressionist brother, but from the second generation of the School of Paris. Following in the footsteps of the Fauves, Soutine travelled to the south of France in the early 1920s and brought back landscapes whose elements appeared to have been pitched askew in a gale with colors twisted together. These landscapes resonated with Holman as expressions that were at once turbulent and joyous. Oskar Kokoschka [Austrian, 1886–1980] was another painter of that generation whose intense expressionist landscapes could add him to this brotherhood.

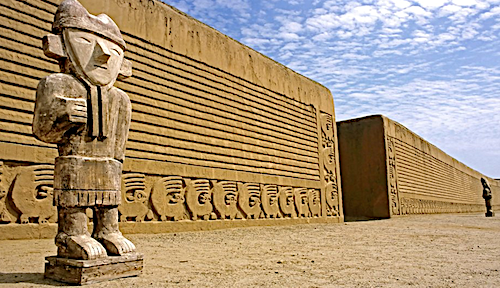

FARTHER SOUTHWEST

By 1983, Holman had found Santa Fe too crowded and his hacienda too cold in the winter, so he moved farther southwest to Tucson. Extended travel ensued, with return trips to Central and South America. Ever since he was a boy traveling with his family throughout Mexico he held an abiding interest in the Aztec empire and the designs of their ancient capital, Tenochtitlan. He was also inspired by Mayan culture and explored their monuments in the Yucatan and Guatemala. Now he explored further, into Bolivia, Chili, and Peru, learning more about the Incas. In 1984 he spent a month in Peru’s northern coast, observing the ruins of Chán-Chán and the archaeological sites of the Pre-Incan civilizations of the Moche and Chimú. He even spent a month in Russia exploring its art collections. When he returned to his studio he was revitalized, continuing his strict regime of long hours of uninterrupted painting.

In 1996, seeking further solitude, Holman moved 60 miles south of Tucson to Nogales, right on the border with Mexico. There he built a house and spacious studio, just a stone’s throw from the border fence. The region is very hilly, and he fell in love with the nearby Catalina, Santa Rita, and Tucson mountain ranges rising above the desert — all with their atmospheric beauty. His reverence reverberates through his paintings, and in his studio, one always finds several canvases upon easels giving testimony. Typically, each is at a different stage but exploring the same view. Monet’s practice of working in series immediately comes to mind — the water lilies on his pond at Giverny, the haystacks in the field near his home, and the cathedral at Rouen. Holman applied his pigments thickly and aggressively before moving on to the next canvas. Each surface bears the tactile quality lent by the impasto of layers of pigment. One practical reason for working in a series is that he must allow the oil to dry for several days before applying the next layers. When he returned, he purposely left visible the evidence of earlier underlying pigments — pentimento — to play important roles. After all, Holman the archaeologist treasured and honored the past, allowing those voices to be tangibly observed. His practice of pentimento conformed with his ingrained need to hear those voices of artists from the many ancient cultures he studied. Those voices are especially punctuated by the Native Americans whose sacred land was overtaken in the nineteenth century by a culture of Manifest Destiny, a dogma that lacked any spiritual literacy to “read” the meaning of those lands. In Holman’s canvases, these deeper meanings explode as lyrical expressionist landscapes.

“My paintings are like American music,” he said. “Not slick like Broadway music, but more like that of Stephen Foster, Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer, and Hoagy Carmichael.” Carmichael was the prolific songwriter from the Midwest who wrote enduring hits like “Georgia on My Mind,” “Heart and Soul,” “Deep Purple,” and “Stardust.” The lyrics of “Stardust” could very well be about one of Holman’s landscapes:

And now the purple dusk of twilight time

Steals across the meadows of my heart

High up in the sky the little stars climb

Always reminding me that we’re apart

You wander down the lane and far away

Leaving me a song that will not die

Love is now the stardust of yesterday

The music of the years gone by.

ENERGY IN THE STUDIO

Upon entering the spacious studio in Nogales, one was greeted by the soft sounds of classical music, which ranged from Debussy to Ravel. Throughout the large rooms of this vast studio-home every wall was covered with art. Beginning in 2010, Holman experienced macular degeneration — like Monet — a condition that only spurred him to become even more prolific. His paintings hung everywhere — some in conversation with works by his friends while others were interspersed between his collections of Mexican retablos and Santa Fe tin frames. This environment of visual delight was further enhanced by the discovery of whole walls displaying his collection of arrowheads, including some of the earliest prehistoric flints in America. Pre-Columbian pottery and antique Native American pots sat atop antique tables, often joined by nineteenth century American primitive carvings of animals such as pigs, snakes, and birds. As he passed by a group of prehistoric pots, he commented that they inspire him every day. They were found about a hundred years ago at the archaeological complex, Casas Grandes, which later became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and they came from the collection of William Randolph Hearst. Other tables displayed 19th century American wedding crystal, including “broken column” cut glass. The floors were decorated with the artist’s majestic collection of antique rugs from Morocco and Tibet.

Holman was a master who was a regular in the New York art world but didn’t fit neatly into a period when serial movements — from AbEx to Pop to Minimalism to Conceptualism — were de rigueur, with the newest style eclipsing the last. Instead, he slipped away to the Southwest where he could focus in peace and meditate on what the land — and art — really meant. He found peace — and fervor — in the mountains, hills, and desert. Holman had finally realized his purpose of making the sublime visual. It’s an energy that reverberates through his paintings.

“Painting is my way of life,” he said. “The 16th century philosopher Michel de Montaigne declared, ‘I want us to be doing things, prolonging life’s duties as much as we can. I want death to find me planting my cabbages, neither worrying about it nor the unfinished gardening’.” Holman added, “I, too, would like to be found at the end of my life in my unfinished garden, in the midst of one last painting.”

— Peter Hastings Falk, 2023

FOOTNOTES

The author personally conducted interviews and visits with Bud Holman in 2018–19. Insights were also gained from his nephew, Calvin Holman, who has cared for the collection upon Bud’s passing in May 2023.

1 Wenzl, Roy. “Its Location a Mystery, Huge Indian City May Have Been Found in Kansas,” Kansas City Star, 17 April 2017

2 Stein, Sadie. “A Secret Little Glass Home in the Heart of New York,” The New York Times Magazine, 23 March 2017

3 Leo Castelli curated this exhibition for artists who had been overlooked by museums. He originally titled the first exhibition in this series “Today’s Self- Styled School of New York Artists.” As it was first held at a pop-up space on Ninth Street, it became known as the Ninth Street Gallery or the Ninth Street Show.

4 In addition to the old sail-loft buildings, many along South Street were hotels and flops. By the late 1950s– early 1960s the South Street Seaport area had attracted more artists, including Chryssa, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, Lenore Tawney, and Jack Youngerman.

5 Credit must be given to Sari Dienes [1898–1992], who was an important but nearly forgotten pioneer in collage and assemblage in New York during the late 1940s. Willem de Kooning [1903–1997] also worked in collage at that time but only briefly. During the mid 1950s Dienes exhibited a series of collages at Betty Parsons Gallery that she had made with found objects as well as rubbings from the city’s sidewalks on large sheets of paper. Among her studio assistants were the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Her works were also included in the American Federation of Arts touring exhibition Art and the Found Object in 1958-59 as well as the MoMA assemblage exhibition of 1961. The collage medium was most fully adopted by the Italian-American Conrad Marca-Relli [1913–2000] who from the 1950s and throughout his long career produced large- scale collages often layered with fabric, leather, metal, or vinyl in contrasting shapes of black and dark earth tones against lighter shapes of whites, creams, and beiges.

6 Howard Hodgkin: Forty Paintings, 1973–1984 (exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1984, p.97)