Unwrapping the Mystery of New York’s Wrapper

Rescuing a Lifetime of Work

Jared Whipple never intended to become an art detective. That new episode was triggered by a phone call on September 22nd, 2017, from a friend who ran a trash removal  company. The contractor said he was cleaning out an old barn and disposing of all its contents. Whipple was curious but had no idea about those contents. He had run his own mechanics shop, “Do It All Auto,” in Waterbury, Connecticut, since he was nineteen. Plus, he shared the adventurous spirit of the hosts of the television show, “American Picker,” who focus especially on collecting items relating to vintage cars and motorcycles.

company. The contractor said he was cleaning out an old barn and disposing of all its contents. Whipple was curious but had no idea about those contents. He had run his own mechanics shop, “Do It All Auto,” in Waterbury, Connecticut, since he was nineteen. Plus, he shared the adventurous spirit of the hosts of the television show, “American Picker,” who focus especially on collecting items relating to vintage cars and motorcycles.

The next day Jared and his friend George drove through the rolling hills of the countryside. The fall foliage season had only slightly begun to emerge in the area’s state forests. Their destination was Watertown, which lays claim to the great “Oak of 1812.” It’s where the new but short-lived American flag sporting 15 red and white stripes (instead of 13) was first unfurled. Driving up a long winding access road, they eventually arrived at the property with two barns and four farmhouses. The contractor was waiting at the largest barn. It was built in the early 19th century. Its fieldstone foundation was nestled into the hillside and its dark red siding showed many years of weathering. Just outside the barn’s bays three young men paused from their labor. They had been carrying large paintings, one-by-one, and carefully stacking them upright in the Dumpster. The contractor had instructed his men to begin systematically stacking the paintings from the back wall of the Dumpster and he fully anticipated filling its capacity of 40 cubic yards. It was 22 feet long, 8 feet wide, and its walls rose 8 feet high. Suddenly, the Dumpster made him imagine the life’s work of his uncle Scott — a “starving artist” — being tossed out. “It was a gut-wrenching feeling,” he recalled, “so right then I felt I had to save them.”

The next day Jared and his friend George drove through the rolling hills of the countryside. The fall foliage season had only slightly begun to emerge in the area’s state forests. Their destination was Watertown, which lays claim to the great “Oak of 1812.” It’s where the new but short-lived American flag sporting 15 red and white stripes (instead of 13) was first unfurled. Driving up a long winding access road, they eventually arrived at the property with two barns and four farmhouses. The contractor was waiting at the largest barn. It was built in the early 19th century. Its fieldstone foundation was nestled into the hillside and its dark red siding showed many years of weathering. Just outside the barn’s bays three young men paused from their labor. They had been carrying large paintings, one-by-one, and carefully stacking them upright in the Dumpster. The contractor had instructed his men to begin systematically stacking the paintings from the back wall of the Dumpster and he fully anticipated filling its capacity of 40 cubic yards. It was 22 feet long, 8 feet wide, and its walls rose 8 feet high. Suddenly, the Dumpster made him imagine the life’s work of his uncle Scott — a “starving artist” — being tossed out. “It was a gut-wrenching feeling,” he recalled, “so right then I felt I had to save them.”

Jared returned to the barn with his flatbed trailer used for hauling cars, and George brought his truck. As they removed the paintings from the Dumpster and loaded them on the trailer, it was difficult to see the paintings’ surfaces because decades earlier each had been wrapped in a protective plastic sheet. These translucent cloaks had yellowed with age and bore the accumulation of years of dirt, grime, and animal droppings. Halfway through carrying out the paintings, a few appeared that were wrapped in cleaner plastic sheets. In the sunlight a few of those surfaces seemed to come alive, calling to Jared as if they were trying to peer through. Jared was struck by what he saw. Many of  the paintings revealed cars and parts whose shapes appeared to be wrapped up in a white fabric. “Being a mechanic my whole life, I was able to pick out many hidden car parts and noticed a bio-mechanical theme going on with some of the artwork.” Besides the familiarity with cars, Jared had an epiphany. “It was something that fine art had never done to me before,” he reflected. At that moment he had the sinking feeling that the huge Dumpster was more like a 7,000-pound iron coffin. These paintings were still alive. They were breathing life and should not be sentenced to be buried alive in a landfill. They had a story to tell. Without any art history training, Jared was nonetheless bombarded with sensory messages that over-rode the paintings’ environment and their terminal fate. Whether the artist was famous mattered little to him. He assumed that these paintings had not been created by a famous artist because, after all, they would otherwise have never been thrown away. Perhaps, he mused, some of those paintings might be suitable decorations for his expansive garage — a large part of which he had converted into an indoor skateboard park called The Warehouse. The word had spread quickly, attracting a cult-like following challenged by its big bowl as well as a meticulously built half-pipe. Since its completion, every Friday night avid skateboard enthusiasts from all over New England have congregated at The Warehouse, animating it with a live band, beer, and of course, skating. One is struck by the park’s interior with its smooth ash bowls recalling the scooping biomorphic sculpture of Jean Arp. Hanging on the surrounding walls is a collection of street-style paintings by the skaters as well as their own painted skateboards.

the paintings revealed cars and parts whose shapes appeared to be wrapped up in a white fabric. “Being a mechanic my whole life, I was able to pick out many hidden car parts and noticed a bio-mechanical theme going on with some of the artwork.” Besides the familiarity with cars, Jared had an epiphany. “It was something that fine art had never done to me before,” he reflected. At that moment he had the sinking feeling that the huge Dumpster was more like a 7,000-pound iron coffin. These paintings were still alive. They were breathing life and should not be sentenced to be buried alive in a landfill. They had a story to tell. Without any art history training, Jared was nonetheless bombarded with sensory messages that over-rode the paintings’ environment and their terminal fate. Whether the artist was famous mattered little to him. He assumed that these paintings had not been created by a famous artist because, after all, they would otherwise have never been thrown away. Perhaps, he mused, some of those paintings might be suitable decorations for his expansive garage — a large part of which he had converted into an indoor skateboard park called The Warehouse. The word had spread quickly, attracting a cult-like following challenged by its big bowl as well as a meticulously built half-pipe. Since its completion, every Friday night avid skateboard enthusiasts from all over New England have congregated at The Warehouse, animating it with a live band, beer, and of course, skating. One is struck by the park’s interior with its smooth ash bowls recalling the scooping biomorphic sculpture of Jean Arp. Hanging on the surrounding walls is a collection of street-style paintings by the skaters as well as their own painted skateboards.

Jared had just passed the “innocent eye test.” The nature of his visceral response was characterized as “significant form” by the great art critic Clive Bell a hundred years ago. The more pressing concern for Jared was his realization that he was confronted with a moral issue. Within his emotional roller-coaster he sensed a cultural imperative that it was simply wrong to trash a lifetime of creativity. “This was not being an art historian — This was about passion versus PhD,” he said. That issue became more poignant when he entered the artist’s studio on the second floor of the huge barn. He saw that the artist had freely sketched and written notes on the walls, as if he had left behind important clues to be discovered. For these reasons Jared was certain about rescuing the paintings and letting them breathe again, if only on the walls and ceilings of his indoor skateboard park.

Jared’s arrival proved to be at the eleventh hour. The contractor confessed that in the preceding days he and his team had filled the Dumpster twice — mostly with large heavy metal sculptures — and carted them to the dump. Those loads had already been processed through a huge crusher machine and buried in a landfill. Fortunately, all of the artist’s paintings and even a group of sculptures, had been held back as the last to go. Several trips later, and with the help of friends, the artworks filled 2,000 square feet of The Warehouse. All were rescued.

Jared’s arrival proved to be at the eleventh hour. The contractor confessed that in the preceding days he and his team had filled the Dumpster twice — mostly with large heavy metal sculptures — and carted them to the dump. Those loads had already been processed through a huge crusher machine and buried in a landfill. Fortunately, all of the artist’s paintings and even a group of sculptures, had been held back as the last to go. Several trips later, and with the help of friends, the artworks filled 2,000 square feet of The Warehouse. All were rescued.

The next step was to document and photograph every painting, and in the process hopefully discover the artist’s identity. Upon discarding the paintings’ old plastic sheets, the  signature “F. Hines” was consistently revealed but it was unhelpful because no candidates could be found in reference books on American artists. Many paintings later, Jared discovered the only one that was fully signed. It was as if the artist made a grand concession by signing, “Francis Mattson Hines, 1961.” With the help of his uncle, Scott, the next two months were spent sorting and categorizing sixty years of art.

signature “F. Hines” was consistently revealed but it was unhelpful because no candidates could be found in reference books on American artists. Many paintings later, Jared discovered the only one that was fully signed. It was as if the artist made a grand concession by signing, “Francis Mattson Hines, 1961.” With the help of his uncle, Scott, the next two months were spent sorting and categorizing sixty years of art.

How to Become Overlooked

During the course of the next year fragments of a compelling story gradually emerged from the rescued archival materials that led to further research on Francis Hines. He was born in Washington, D.C. in 1920. He attended the Cleveland School of Art from 1930–1942. He then served in World War II in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Photo Reconnaissance Unit for Military Intelligence in the China/Burma/India theater. At the end of the war he settled in New York, working as a freelance artist, and was briefly married. This period marked the beginning of his double life as commercial illustrator and a painter of both abstract and figurative expressionism. He remarried in 1949 and a few years later moved to Hartford Connecticut, where he held the position as chief commercial artist at G. Fox & Co., then the largest privately held department store in the country. From the late 1950s to the early 1970s he lived closer to New York and achieved continued success as an illustrator, especially of interior architecture, design, and furnishings. 1

In 1976 Hines moved from Ridgefield to Watertown, Connecticut, where a rented the large barn that became one of his studios — as well as the repository for all of his art. This was also the year he purchased a condominium on 11th Street at West Street. The next year he also took a studio at 325 Bowery at the corner of 2nd Street in NoHo. His studio loft was located directly above the famous jazz club, “The Tin Palace.” Besides attracting great jazz musicians, the club’s regulars included famous poets; and, among the artists were Joan Mitchell, Robert Indiana, Larry Rivers, Robert Frank, and the recently rediscovered Michael Goldberg. The duo Black Music Infinity — saxophonist David Murray and drummer Stanley Crouch — regularly performed upstairs in Hines’ loft.

As Hines’ story was gradually pieced together it became clear that he was a master whose chapter in American art history was nearly lost forever. His powerfully evocative images were created in a uniquely innovative style and technique that had no predecessors. So, how could it come to pass that his life’s work wound up in a Dumpster? The answers for his disappearance are found in studying the back stories of other brilliant artists who slipped into obscurity but were rescued by guardians like Jared. Brilliant careers can get derailed for a dozen primary reasons, the majority of which are tragic. Destruction is at the top of the list, many owing to calamities such as fires and floods. Destruction can also be owing to human willfulness, neglect, or an impending legal deadline preventing a hoped-for solution. The latter turned out to be the case with Hines. Tragically, the bulk of collections that have faced destruction have disappeared forever, perhaps with only a few surviving works and archival evidence in photographs and writings having been left behind as tantalizing testament to the artists’ significance.

Psychological reasons also vie for the top spot. Psychotic breaks are the worst of it, but more common are those artists who are simply irascible characters at odds with the world, shunning both gallery owners and museum curators. Some are in contempt of what they see as a demeaning process for gaining attention in a market they see guilty of commercializing art as a commodity. Either bad experiences or personal tragedies can serve as catalysts for driving some artists into becoming reclusive at best or agoraphobic at worst. Addiction to drugs or alcohol have cut short the lives of some brilliant contemporary artists — from Pollock to Basquiat — but enhanced their mythic status. The majority, however, suffer the far greater risk of their legacies never becoming appreciated.

“Quality” in art — which is the prerequisite for recognition — means true innovation and significance compared to the work of an artist’s more famous peers along the historical timeline. Those following derivative paths need not apply. However, there are also cultural biases that have long held back artists, and the top among them are race and gender. Fortunately, the turn into the 21th century has seen both museums and galleries reassessing the quality and importance of art created by women and people of color. Another powerful external force that can knock artists out of contention is financial necessity, de-railing many during periods of economic recession. Full-time non-artistic jobs can gradually reduce the time and inspiration needed to command the spirit and focus the creative side of the brain. Many artists have been successful in achieving a measure of financial security by balancing steady income-producing jobs with the private sides of their artistic lives. Committed to schedules of intense creativity, artists leading such double lives often become prolific but with the typical side-effect of lacking the time or desire to follow up with self-promotion.

For a rare few, great family wealth has provided a financial security that, ironically, has served as the ultimate insulator from the market in which most artists are struggling to become established. Wealth eliminates any pressing need to canvas the galleries and subject oneself to the fear of possible rejection and humiliation. Wealth can eliminate any notion that the artist is painting to satisfy a trend just to make money. Perhaps most important, wealth can allow an artist to follow a spiritual path in art without being interrupted by the usual day-to-day external noises. They are allowed to meditate, to consistently do deep dives to discover their true creative selves and then reflect those visions in their art.

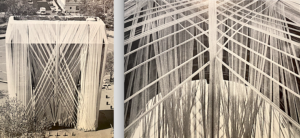

The back story on Francis Hines reveals an artist who received critical acclaim forty years ago but purposely chose to slip into obscurity. His spectacular wrapping of the Washington Square Arch in 8,000 yards of white polyester fabric lasted only a week in 1980 and had left the city awestruck. It did not take long for the art world to forget. Nick Weber, who shared studios with Hines in Manhattan for fifteen years and refers to him as his mentor, said it was not surprising that his friend later slipped into obscurity. “Hines fell through the cracks,” declared Weber, “because he had to fall through the cracks. The cracks are the only place where unconditional creativity exists. His work had touched a power unrecognizable to the commercial art world — a world which itself is so corrupt that it took a car mechanic to sense its inherent value as it lay in a Dumpster, and then rescue it and reveal it.” 2 Indeed, just a month after Jared had rescued the collection, the New York City Parks Department featured Hines’ Washington Square Arch masterpiece as one of the “Top 10” most memorable public art installations in the city’s history. That coincidence was never matched with the artist’s passing, so no one wondered whatever happened to him. No one ever thought to ask if a collection had ever been left behind.

Hines was an outsider who refused to let his creative pulse be driven by ego. The painter Beverly Brodsky reconfirmed the philosophy by which he lived. She described her friend as one who was passionate about being in the studio every day creating art, passionate in talking about it, but completely lacking any interest in becoming promoted in the art market via the bustling gallery scene. “Though his research seemed methodical, his brilliant drawings were never calculated. These ‘Organisms,’ as he called them, were entirely intuitive, as though he was connected to a great mystery or an inexplicable power in the universe which impelled him to push forward and expand.”3

Unwrapping Other Wrappers

There are not many wrappers in 20th century art. Christo [1935–2020] has emerged as the most famous but he was not the first. Few may be aware that the original wrapper who inspired Christo was Man Ray [1890–1976]. In 1920, Man Ray wrapped a sewing machine in blanket, bound it in twine, and called it L’Enigme d’Isidore Ducasse. During the 1920s he and other Dadaists and Surrealists in Paris — such as Dali, de Chirico, and Magritte — included wrapped objects as enigmatic elements in their paintings, thereby making their subjects unclear or even disconcerting. The history of wrapped objects then jumps forty years to Christo wrapping empty paint cans in his Paris studio in 1958. By the 1960s he and his wife, Jeanne-Claude, had wrapped objects such as a motorcycle, a Volkswagen, an uprooted tree, and a woman. In 1964 they moved to New York for good and by 1975 had completed all of their concept drawings for wrappings even though most projects would not become realized until many years later. This explains why the style and technique of Christo projects remained so consistent, from his first building wrapping in 1968 (of the Kunsthalle in Bern, Switzerland) to his posthumous one — the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, slated for 2021.

Coincidentally, Hines moved his work from two- to three-dimensionality during the mid 1960s by embedding numerous found objects into a series of diorama-like wall hangings featuring historical figures dutifully wrapped in tin foil and various fabrics. “It was not long before the wall constructions evolved into free-standing pieces,” wrote Sonra Ross, his wife. “Often these constructions consisted of plaster female forms contained in box-like enclosures, effecting an eerie sensuality capable of moving and disturbing even the most casual viewer.”4

Both Christo and Hines invited viewers to experience a structure’s physical form in a different way. They prompted viewers to reappraise form and space — lending surprisingly new sculptural qualities to architecture. However, their final works were strikingly different. Christo was a conceptualist, a visionary who emerged from the Dadaist tradition of Man Ray. He covered structures in translucent polyethylene sheets and then bound the whole mass with ropes. The final wrapped bulk suggested the identity of the original form, but its three-dimensional volume was simplified into its basic mass. Hines, on the other hand, emerged with a completely new approach to wrapping that was distinctly separate from that of Christo. His pursuit was aesthetic, not conceptual. It was not about loosely wrapping up a form. It was instead about tightly weaving diaphanous synthetic fabrics into geometric patterns, stretching them over a building’s facades under hundreds of pounds of pressure.

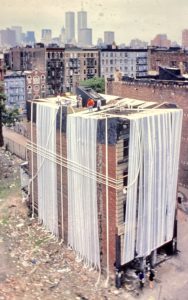

Hines remains the only artist to ever wrap a building in Manhattan. His first, in 1978, was a run-down tenement building on East 10th Street between Avenues C and D in the East Village. He wrapped 1,500 yards of heavy white synthetic gauze fabric over its façade, creating a powerful sense of tension within a symmetrical pattern. There was also an inherent tension in the dangerous neighborhoods where he chose the abandoned buildings inhabited by drug addicts and controlled by gangs. Because this building had been slated for demolition, the media interpreted his purpose as being one that would draw attention to the socio-economic plight of the neighborhood. While Hines was not trying to play the role of artist as social activist, this was the interpretation presented in the newspapers. The media’s reaction to this unique and immense wrapping must have caught Christo’s attention. After all, Christo’s several proposals to wrap buildings in Manhattan all met rejection, including that for the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

Hines second building wrap, in 1979, was also of an abandoned tenement building in the East Village. This one was at 605 East 5th Street, and he again used a heavy white gauze fabric, this time weaving across the entire structure, not just the façade. The newspapers again described the project as espousing a socio-political purpose. Hines later clarified, “The wrap has nothing to do with any social statement. I’m interested in the enormous energy that takes place when these forms are under the tension of binding.”4

The Washington Square Arch and other Public Wrappings

Hines’ wrappings of buildings brought international attention and he was asked to propose a wrapping for Milan, Italy. He declined, however, later explaining that the reason was because he considered himself a very New York-oriented artist. In this spirit, his third New York wrapping was his masterpiece — the Washington Square Arch. In 1979 Hines was approached by Evelynne Patterson, director of community relations for New York University. She explained that the great triumphal arch had long been victim to the larger graffiti blight, which had spread through the city in epidemic proportions. It was dire need of cleaning and a funding campaign was underway. “We’ve worked for five years to find a solution to the arch graffiti problem in order to call attention to the terrible condition of this monument, and in fact all monuments in this city.”5 To add insult to injury, early in 1980 a careless film crew had unlawfully painted a large area of its base in silver paint as a backdrop during a shoot for a Marilyn Monroe movie.

Hines’ wrappings of buildings brought international attention and he was asked to propose a wrapping for Milan, Italy. He declined, however, later explaining that the reason was because he considered himself a very New York-oriented artist. In this spirit, his third New York wrapping was his masterpiece — the Washington Square Arch. In 1979 Hines was approached by Evelynne Patterson, director of community relations for New York University. She explained that the great triumphal arch had long been victim to the larger graffiti blight, which had spread through the city in epidemic proportions. It was dire need of cleaning and a funding campaign was underway. “We’ve worked for five years to find a solution to the arch graffiti problem in order to call attention to the terrible condition of this monument, and in fact all monuments in this city.”5 To add insult to injury, early in 1980 a careless film crew had unlawfully painted a large area of its base in silver paint as a backdrop during a shoot for a Marilyn Monroe movie.

In May, Hines and a team of 23 women and men, many artists, set to work weaving eight-thousand yards of synthetic white fabric over the whole arch. After stretching and crisscrossing each long piece of fabric into a geometric pattern, their ends were tightly secured around thick iron loops at the base and anchored with heavy knots. The completed work not only left the public awestruck but even surprised Hines. In the PBS documentary that followed, Patterson Sims, then curator of the Whitney Museum of American Art, asked Hines if he was pleased with the huge project. “After the second day of wrapping,” Hines replied, “after night had fallen and it was dark, I could see what was starting to happen, and it started blowing my mind. It was almost as if I hadn’t done it at that point. And with any good work of art you should, I think, have that feeling…that something other than you had something to do with it…with your conscious planning mind and the whole thing.” Hines then paused and added, “I knew it would be conceptually successful, but I’m not a conceptual artist. I knew that being conceptually successful was not going to be enough…There’s already enough confusion with Christo, so I knew that sort of thing wouldn’t be particularly helpful.” 6

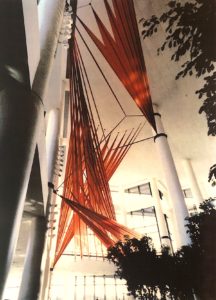

Clearly, Hines’ aesthetic objective of inserting tension into pattern was, in spirit, far from Christo’s conceptualism. Instead, Hines found a greater kinship with the works of geometric sculptors employing linear forces. The work of Richard Lippold [1915–2002] is a good example even though his medium (gold wire) was quite different. During the 1950s–60s Lippold stretched myriad gold wires fanning in tight geometric patterns to produce monumental hanging constructions, most of which are now installed in major institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Much of the artistic momentum for projects of monumental scale in the 1970s can be traced to the Earth Art movement of the late 1960s. This approach merged Minimalism and the environment, using the natural landscape as the medium. Michael Heizer [b.1944] turned a large expanse of the Moapa Valley on Mormon Mesa near Overton, Nevada into Double Negative in 1969. Most famous is the Spiral Jetty, created by Robert Smithson [1938–1973] in 1970 at Great Salt Lake in Utah. The movement was named in 1969 after its first museum exhibition — Earth Art — at Cornell University, inspiring other artists such as Richard Fleischner and Walter de Maria. During the mid 1970s Gordon Matta-Clark used abandoned buildings as his medium and his projects were distinguished by huge holes cut into concrete walls and floors. His last project, Circus or The Caribbean Orange, was completed just before he died in 1978 — just a few months before Hine’s first building wrap.

Much of the artistic momentum for projects of monumental scale in the 1970s can be traced to the Earth Art movement of the late 1960s. This approach merged Minimalism and the environment, using the natural landscape as the medium. Michael Heizer [b.1944] turned a large expanse of the Moapa Valley on Mormon Mesa near Overton, Nevada into Double Negative in 1969. Most famous is the Spiral Jetty, created by Robert Smithson [1938–1973] in 1970 at Great Salt Lake in Utah. The movement was named in 1969 after its first museum exhibition — Earth Art — at Cornell University, inspiring other artists such as Richard Fleischner and Walter de Maria. During the mid 1970s Gordon Matta-Clark used abandoned buildings as his medium and his projects were distinguished by huge holes cut into concrete walls and floors. His last project, Circus or The Caribbean Orange, was completed just before he died in 1978 — just a few months before Hine’s first building wrap.

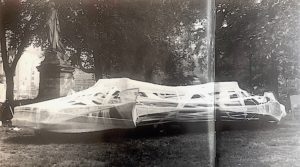

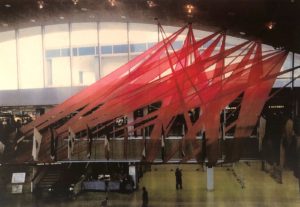

Hines had transformed the Washington Square Arch into an exotic modern cathedral. Shortly after unwrapping it ten days later he pursued other public wrappings. He produced a large series of project drawings for his proposals for wrapping each of the monuments in Union Square but they were unrealized. However, in September 1980 he wrapped Bound Police Cars in Union Square Park. In 1981 he installed Suspended Sculpture in the New York Port Authority Bus Terminal. In 1982 he performed an unauthorized “guerilla wrapping” of a section of the old Westside Elevated Highway while it was in the process of being demolished. This time the white synthetic fabric was stretched between the last remaining massive iron girders, both vertical and horizontal. In 1983 his Celebration in Flight was installed at the JFK International Airport Arrivals Building in celebration of its 25th anniversary. It was composed of 825 yards of red parachute nylon extending 100 x 50 ft — and was in conversation with Alexander Calder’s nearby 45-foot mobile, .125 from 1957 (later re-named Flight).7

A Unique Energy within the Painting-Sculpture

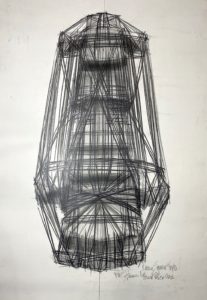

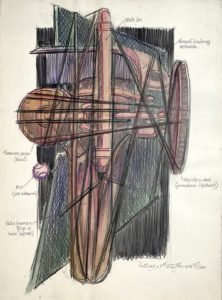

A few days before Jared Whipple arrived on the scene on September 23rd, 2017, most of Hines’ sculptures had been recycled for their metal or had become part of a landfill. Fortunately, fifteen were saved. In addition to the collection of paintings, also preserved were hundreds of large drawings and archival photographs. After reviewing these materials, the artist’s process, mission, and trajectory became clear. Hines was a meticulous and prolific draftsman. He first envisioned every project and sculpture in drawings — numerous drawings — which he later faithfully followed. His sculptures often began as cages of welded iron rebar that enclosed salvaged car parts, which were typically suspended by wire cables drawn and cinched tightly through shackles and turnbuckles. In addition to car parts, he also wrapped other objects such as chairs, stools, tables, and mannequins. In one video he described one of his sculptures of a wrapped mannequin: “I began this about forty years ago [1970s] in a figurative way. The actual mannequin of a female body that was involved in a kind of booth — in a cage of its kind — and this has always been a theme that has involved me, both in drawing and construction….When you entrap energy there is a static quality that occurs. Within that static quality there is a tension coming from that object that is being bound, and by the binding itself creating tension — and all of the energy occurs within that tension.”8

It was through tension that Hines lent architectonic force to abstract expressionism. “My building wraps are larger forms of what I do in the studio,” he clarified. The first sculptor to elevate car parts to sculpture was John Chamberlain [1927–2011], the abstract expressionist who in the 1950s merged colorful crushed bumpers, hoods, and other parts into unique forms. Another significant use of cars as sculpture occurred in 1974 when Ant Farm [1968–1978] created Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, Texas. This group of architects half-buried ten old salvaged Cadillacs in a row — an installation that has become iconic in pop culture. Hine’s approach to sculpture was to create power objects. One writer aptly noted “the repeated constricted anatomical elements that pervade the artist’s work, accompanied by the succession of ropes, cable, wrapping, plaiting, and layering of fabrics. This dizzying repetition and complexity is at the heart of Hines’ dynamics of fetishism. One senses the investment of libidinal energy in the creation of the final piece. The viewer finds himself undergoing a charged experience within a generative space.”9

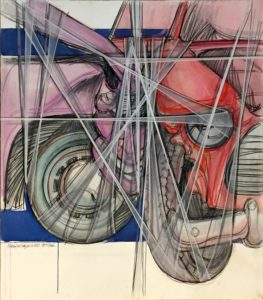

Hines’ glorification of wrecked cars extended from sculpture to painting with his Hoboken Autobody series of 1983-84. Despite the series’ title, he never had to actually trek across the Hudson River to the huge lot of salvaged cars in Hoboken. Instead, he reveled in the numerous abandoned cars right in front of his studio overlooking West Street. The area was littered with cars abandoned after accidents or breakdowns, and they got stripped down so quickly they weren’t worth salvaging. West Street, or “Death Avenue” as it was long known, had a history of numerous car crashes. The fifty numbered paintings in this series range from 3 x 4 ft to 4 x 6 ft and revel in bringing a new approach to abstraction. In his unique technique, Hines continued the spirit of wrapping the cars parts by employing strips of nylon gauze that were tightly stretched and then anchoring them into the work’s wood backing. Each painting thus stresses the linear forces exerted within the imagery.

Mutagenesis

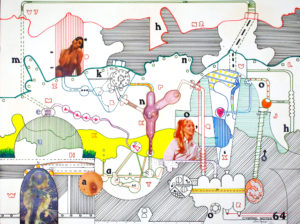

Throughout his career, Hines flexibly alternated fluidly between his wrapped paintings, his wrappings of buildings, and his indoor installations. For example, in 1985 he created an installation for the Merrill Lynch building in the Atrium Complex in Franklin, New Jersey. For the next two years he was back exploring painting, focusing on expressing the sexual symbolism of women and their inevitable transformation in a world of rapidly advancing technologies. His Urban Icons series — which he referred to as “organic mechanical improvisations” — was a theme related that pursued by Richard Lindner [1901–1978] in the late 1950s, evoking the anxiety that flares when technology collides with sexuality. Linder was also a professional illustrator, and he emerged from that role to explore subliminal sexual symbolism and gender roles hidden in media and advertising. With a style rooted in graphic design, Lindner’s later images of women became even more disturbing. They are cyborgs, alienated creatures who are clearly part machine, as reflected in their bright metallic colors. By the 1960s, the concept of cyborgs had been made popular by science fiction.4 However, Hines strictly avoided sci-fi movies and magazines.

Hines was not an apocalyptic alarmist, as was the Swiss illustrator H.R. Giger [1940–2014]. Hines’ was unaware of Giger’s Biomechanoiden series created in 1969 — dystopian illustrations on the human-machine theme. Even when Hines had begun his own exploration of the convergence of anatomy and machine, he was unaware of Giger who by then had achieved acclaim as an illustrator in the sci-fi world owing to his creation of terrifying aliens for the ongoing “Alien” movie franchise.10

Another artist who integrated creativity with futuristic warnings was Don ZanFagna [1929–2013]. His Cyborg Series of collages (1968–1974) serve as “cybernetic metaphors” that focus on the future problems that DNA mixing might cause. They are signals or warnings of things about to wrong. The artist wrote, “These works incorporate humans and machines, cloning, eco-architecture and landscape, biology and technology and make use of dark humor, skepticism, irony, and futuristic symbolism.” The resulting Cyborg environment that ZanFagna constructed shows entities that have lost their humanity and sexuality, but mechanically still reproduce new “humans” replete with nuts, bolts, and robotic controls.

The cyborg women in Hine’s Urban Icons series sometimes appear to be prisoners enduring sadomasochistic aggression. In these often-distressing images, he focused upon individual females who appear to be in the process of transforming into cyborgs. Each painting seems to document a stage in a laboratory experiment. By binding the figures tightly with fine nylon fabric he reinforced the commitment to their transformation. Owing to their foundation in abstraction it can take time to discover the disguised distress. More overt is the surrealism of the “Doll Games” series by Hans Bellmer [1902–1975]. During the mid 1930s he was preoccupied with the process of disjointing groups of prepubescent dolls, reassembling their limbs, and then photographing the final mutation. More terrifying counterparts in contemporary art are found in the zipperheads created by Nancy Grossman in the late 1960s–early 70s, bound and blindfolded in leather head-masks and straps.

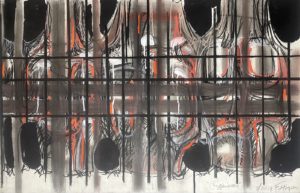

Hines’ female-centric imagery evolved in 1988 and would endure to the end of his life. The Urban Icons Series became superseded by the far more abstract Mutagenesis Series. In this final series exploring the convergence of anatomy and machine, he moved away from those uneasy interpretations implicitly rooted in sexuality and instead postulated a unique aesthetic. In this major series he remained resolute in exploring the forces driving the evolution of human genetics. He saw an era when our increasing dependence upon both mechanical and digital technology promised to inexorably alter human genetic coding. Although the outcome could have implied a dystopia populated by cyborgs, Hines never took the approach of a sci-fi illustrator. He instead focused on the persistent energy and tension inherent in the evolutionary process of mutagenesis. As a result, his paintings at first appear to be complete abstractions. However, careful observation reveals that the painter was still intuitively expressing what he perceived to be a critical evolutionary stage in the transformation of human to machine. In these carefully structured images, Hines merges machine parts with human flesh — and the image is often wrapped tightly with the same synthetic bands of fabric used in the Hoboken Autobody series. He even takes the stance of a scientist, providing a series of drawings illustrating how Mutagenesis works. These drawings seem to make an appeal for becoming the basis for a new edition of the highly influential Gray’s Anatomy. While the subjects of his anatomical drawings look like sculptures wrapped tightly in his signature gauze, he dutifully labels their integral biomechanical parts. The series of drawings are entitled Anatomy Chart of a 20th Century Totem and dutifully name the muscles in Latin. Certain automated parts are suggestively named, such as “headlight (nocturnal eye),” “optic nerve housing,” “nutritional tube,” and “brake mechanism.”

Hine’s Mutagenesis series evokes a rare energy. Ultimately, it is the beauty of these compositions, masterfully utilizing color, that capture our attention even though the artist is alluding to the larger clue that he is an insider urgently presenting evidence of a certain fate that is in the process of unfolding. His images were intended to help us understand the relationship between our bodies and technology. The organic meant flesh, so it appears painted in warm tonalities of reds, oranges, tans, and whites — just as one would see in an anatomy chart. An unconscious tension of vulnerability is created by trapping those organic forms between the geometric forms. Because these paintings so subtlety set a balance between flesh and machine, we instead appreciate the abstract whole. Even when human muscles are clearly painted, they smoothly blend with the technological components. Hines had no interest in shock factor per se, as exemplified by Francis Bacon’s Painting of 1946 (at MoMA) of a hulking carcass of beef behind a menacing caricature of Neville Chamberlain — or the archetypal Le Boeuf of 1923 by Chaim Soutine, depicting a raw and bloody side of hanging beef.

Nick Weber noted that Hines often explained, “I’m interested in nature’s process — not copying it, but doing it, being that process.” In 1994 Hines wrote, “Within the modern city the human animal has become part of a biological/industrial morass, inseparable from the structures and products it creates. Here the human represents but one element in a unique organism of its own making, an organism that is part biological, part structural and mechanical, part electronic. The complexity of this interrelationship constantly increases with ever-advancing technology among these various elements. Is our basic nature being irrevocably modified to accommodate this condition? These drawings express my response to this universal evolvment. In addition, they serve to stimulate my sculpture. The metaphor for the human or organic is human anatomy; for the inorganic I use mechanical devices. These elements are bound together to create a single cohesive organism, symbolizing the interdependence of the animate and inanimate in the city of the late 20th century.”

In 1988, amidst the development of the Mutagenesis series, Hines created yet another wrapping installation, this time called Flight. It was composed of 3,500 yards of parachute nylon (90 x 40 ft) in the atrium of Tower Center Two in East Brunswick, New Jersey (PNC Bank building).

In 2000, Weber and Hines moved to 99 Canal at Forsyth Street in Chinatown. Their studio was formerly a Chinese sweatshop. The next year, at 81 years old, Hines created his last major public sculpture in the Newtown section of central Johannesburg, South Africa. He stacked five salvaged cars in a pyramidal form, the whole wrapped in his signature synthetic fabric. The project, called CrossOvers, was located on the grounds of the Workers Library & Museum.7 During the next ten years Hines continued to produce large sculpture at the Canal Street studio along with numerous drawings inspired by an orthopedist’s MRI images (magnetic resonance imaging).

In 2010 his wife, Sondra, suffered a stroke. She had been an essential force throughout Hines’ career, organizing his projects and their teams. Hines dedicated one of his catalogues to her, declaring that “without her talent and devoted work much of what I’m about would never see the light of day.” Paralysis had left her without speech or the ability to walk, and their son, Jonathan (also an artist) cared for her until she passed away in 2013. As Hines continued to push into his 90s, Nick Weber became more concerned about his friend’s artistic legacy and occasionally asked about the works stored in the country barn in Watertown. While typically avoiding such inquiries, Hines finally turned to Weber and emphatically stated, “Just worry about where you store yourself! Then, when you wake up the next day you can get back to making more art.” Hines exhibited boundless energy working in the studio every day. He continued to push the boundaries of his Mutagenesis Series by creating two extensive sub-series of large pastels where biomorphic forms are overlaid by a grid pattern — again entrapping their energy. These were titled Cages, produced from 2007 through 2011; and, Organisms, from 2012 until just weeks before his death in 2016. In a moment of introspection Hines said, “The artist is basically a reflection of his time and place. I suppose to a certain extent it reflects the social conditions that have surrounded me, as I have developed through my lifetime — and it reflects how I feel about those circumstances. But I prefer not to dwell on that — and I just love the process of making art.” Indeed, Hines was so focused upon creating art in the studio that he avoided dealing with mundane matters such as the entreaties of the barn owner in Watertown who kept reminding him that the property was being readied for sale. Finally, in 2014 the artist who for decades always chose to ride his bike to his studio had a stroke. Shortly after he passed away in 2016 at age 96, the estate had to comply with a tight deadline that was imposed for cleaning out the barn’s contents. When no immediate solution could be found the contents were deemed abandoned and Jared’s friend in trash removal was contracted for the task.

The authenticity of Hines’ uniquely creative approach is best summarized by the artist who knew him best, Nick Weber: “When art itself is an organic process it is evolution of consciousness made visible. If one becomes the evolutionary process one is not in a conditioned state of mind. As a result, our art helps others free themselves. This is in direct opposition to Fascism, a cultural mode of thought inherently bent on cultural homogenization and therefore the destruction of the evolutionary process. One argument posits that the contemporary art world has been under the constraints of a certain form of Fascism that serves to condition the art that makes it to the big stage. However, when art that emerges as unconditioned, untainted, it will spark a higher awareness. That art is dangerous to the system because it encourages a new freedom.”

— Peter Hastings Falk

FOOTNOTES

1 Hines served in WWII from 1943–46 (The Cleveland School of Art became Cleveland Institute of Art in 1948.) In 1957 he was living in Millwood, New York, and was set designer for a play “Ladies of the Corridor” in Chappaqua, New York. The local paper reported, “Francis Hines, as set designer, offered stunning and ingenious backdrops to depict changes from one tenant’s room to another.” (New Castle Tribune, Chappaqua, New York, 12 Dec 1957). From 1960–70 he lived in Ridgefield, Connecticut, where he raised his family.

2 All quotes from Nick Weber are from several interviews with the artist from late 2019 to early 2020. Weber shared a studio with Hines in the landmark Starrett-Lehigh Building at 601 W 26th Street from 1997–2007. In 2008, they moved their studio to 99 Canal Street, where they worked until 2011. In 2008, Weber produced a music video “Girl Problems Band – Mette” in which Hines appeared at age 88.

3 From the 2016 eulogy by Beverly Brodsky, one of Hine’s close artist-friends

4 Ross, Sondra. Hines/Frabric and Tension (Barrytown, NY: Open Book Publications, 1981, p.9)

5 “Cityscape Sculpture” The New York Times, 28 May 1979. Hine’s first building wrap of November 1978 was the subject of a documentary video by June Manton, “Cityscape Sculpture by Artist, Francis Hines” — a New York University Film School Production. In 1979 she produced a second documentary video, “Under Wraps, Francis Hines, Sculptor,” which was presented at the Global Village Video Festival and on WGBH-TV Boston.

5 from the televised documentary, “Francis Hines’ Washington Square Wrap,” Patricia Sides, Exec. Producer, PBS, 1982. At the 1982 American Film Festival, it was awarded Finalist. References to Evelynne Patterson’s role as the executive assistant to N.Y.U.’s president as well as director of community relations can be found in Fiske, Edward B. “Miracle on Washington Square,” The New York Times, 30 April 1978; and, Horseley, Carter B. “N.Y.U. Program of Rebuilding Drawing to a Close” (The Villager, 15 Feb. 1981). See also: Rack, Yannick. “Cut! Arch Movie Paintjob Preceded Park Renovation” (The Villager, 10 March 2016)

6 Ibid.

7 A video was produced by The Port Authority & Art for Public Spaces, “Suspended Sculpture: An Installation by Francis Hines” — Produced and Directed by Paul Kornblueh and Wendy Roberts. The installation remained in place from Oct 25–Nov 22, 1981 at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York. The 1982 Sony National Video Competition awarded it First Place for Documentary. Another video was produced in 1983, “JFK Airport (Celebration Flight): An Installation by Francis Hines” Hines was commissioned by the director art program for the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey to produce the installations at JFK airport wrap as well as the Port Authority Bus Terminal. That director (from 1962–1995) was Saul S. Wenegrat, who was also a professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Wenegrat was also in charge of the art for the World Trade Center’s twin towers. Among Hine’s unrealized installations were proposals for the towers’ lobbies; and later, for the 9/11 Memorial & Museum.

8 video credit

9 Nahas, Dominique. Silent Disclosures: Selected Works by Francis Hines (privately published ca.2002)

10 H.R. (Hans Ruedi) Giger [1940–2014] was a contemporary surrealist illustrator who began painting foreboding monochromatic landscapes/dreamscapes skillfully portrayed in the airbrush medium. In 1969 he began a series on the biomechanical human-machine theme called Biomechanoiden. The series continued with images such as Brain Salad Surgery in 1973. His purely biological interpretations of alien life won him acclaim in 1979 when they guided the first “Alien” movie — which has continued to be a major franchise. That work won an Oscar and international recognition followed throughout the 1980s, reinforced by his frequent illustrations during the run of Omni magazine from 1978 to 1995.

9 Ross, p.11

7 The term Cyborg — short for “cybernetic organism” first appeared in 1960. By 1980, DC Comics had introduced a man-machine system as a superhero called “Cyborg.” A plethora of human/robots have appeared ever since, often possessing superior strength, senses, and even weaponry — often with bizarre psychological consequences.

7 CrossOvers was organized by CrossPathCulture (founded in New York in 1998).

EXHIBITIONS

2021 Retrospective, Mattatuck Museum of Art, Waterbury, Connecticut

2006 Gallery 384, Catskill, New York (drawings)

1997 Vorpal Gallery, New York

1993 Galería Atenea, Sam Miguel Allende, Mexico “20th Century Totems”

1990 Vorpal Gallery, San Francisco

1989 Vorpal Gallery, New York

1977–81 Stewart Neill Gallery, 136 Greene Street (ca.1977-81) exhibited the wrapped sculptures.

1965 Smolin Gallery, New York — Abstract Paintings by Francis Hines. Located on 57th Street, Smolin was an avant-garde gallery of the 1960s.

1948 Collectors of American Art, Inc. At age 28, Hines won an art competition at this organization, which was active from around from 1937–1959 at 38 West 57th St. By 1939 they had nearly 300 “members.”