Evoking the Metaphysical Power of Color

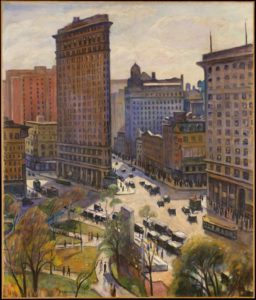

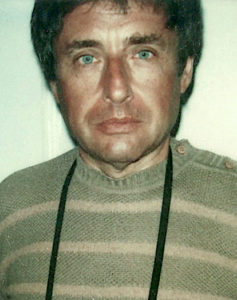

At what point can the passion for collecting art cause one to completely quit one’s business expertise and jump heart and soul into becoming a painter? Sol Ethe received his MBA from Columbia University in 1946 and became a key statistician at the Econometric Institute and then with W.R. Grace. But in 1959 he quit economics. His transformation had been germinating since tghe early 1950s owing to regular visits to Madison Avenue galleries where he acquired works by Leger, Picabia, Klee, Cornell, Miro, Mondrian, Severini, Malevich, Delaunay, and Kupka. During this early period he was so possessed by their works that he not only researched their lives and philosophies but by 1955 had begun quietly teaching himself to paint at his 25 Fifth Avenue apartment in Greenwich Village. Even though the that notorious hangout for artists, Cedar Bar, was right around the corner, Ethe was never attracted to its raucus environment. Right after quitting his job in 1959 he took the entire top floor in the 1897 Sohmer Piano Building farther down Fifth Avenue on 22nd Street in the Flatiron District. It would remain his studio for the next eight years. Every day he would walk to his new “job” dressed in business attire and upon arrival change into his paint-speckled studio clothes. At day’s end he reverted to his coat and tie and walked back home. In this play upon appearance versus reality, passersby would never suspect he was a painter.

Along his path of self-discovery Ethe was soon inspired by the Russian mystic and spiritualist George Gurdjieff [ca.1866–1949], who had built a following in New York since the 1920s. In the early 50s the Gurdjieff Foundation (to which Ethe belonged) was opened in New York by one of his closest followers, Jeanne De Salzmann. Gurdjieff proposed proposed that contemporary civilization had destroyed the soul of artists because they were too often driven by their egos. They had left behind the original sacred obligation to create art that served as a catalyst in the process of society’s conscious evolution towards greater understanding — and the transformation of art’s individual viewers. For example, Gurdjieff saw Far Eastern art as a precise form of communication reaching people whereas Western art had become based in philosophy and conceptualism. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of Gurdjieff’s ardent followers and thought of him as a great artist. Among the painters Gurdjieff influenced were Walter Inglis Anderson [1903–1965] — the reclusive modernist whose eponymous museum has preserved his deep connection to the sea life of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Another was Joseph Cornell [1903–1972], with whom Ethe became a close friend. They were drawn together owing to their spiritual imperative for creating art. Cornell was reclusive and Ethe was a quiet and thoughtful friend. They also shared a pursuit of collage. Ethe visited Cornell at his home on Utopia Parkway many times, where Cornell hung one of his friend’s paintings. Two other good friends who were aware of Gurdjieff’s enlightenment that art should express a higher state of consciousness were De Hirsh Margules [1899–1965] and Irene Rice Pereira [1902–1971]. Shortly following Ethe’s first solo exhibition at a Madison Avenue gallery in 1963, Margules wrote, “Solomon Ethe is gathering his own worldly symbol gestalt in ways that are not discovering the ghosts or anthropomorphic demanding bodies”(1) Irene Rice Pereira, a founding member of the Design Laboratory in New York, appreciated the geometric symbolism in Ethe’s paintings. She encouraged experimentation toward discovering a philosophically transcendental approach to art.

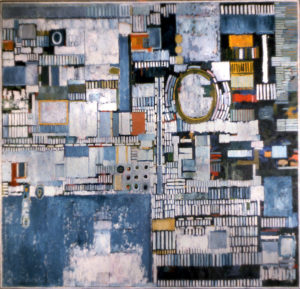

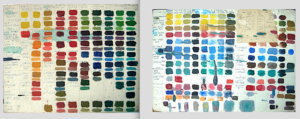

In 1966, one of Ethe’s large canvases (78 x 92 inches) was accepted for the annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 161st Annual, Philadelphia (No. 281: Untitled, 1964–65). Two years later, another was exhibited at the Gallery of Modern Art at 2 Columbus Circle (now the Museum of Arts & Design); and, in 1974 his work was selected for the annual exhibition of the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art. This momentum continued throughout the 1970s when Ethe’s studios were in SoHo — first on Greene Street near Spring Street and later on Wooster Street near Prince Street — at locations that made studio visits easy. A dozen exhibitions would follow, along with favorably insightful critical reviews that from the beginning consistently noted Ethe’s driving theme, “painting is not an expression of the artist’s self-serving ego, but has a higher, more spiritual aim.”(2) In a brief statement, the artist explained why he painted: “Because I am interested in realms inaccessible and inexpressible save through the medium of paint. Accordingly, my work is not in any way representational or does it contain literary references. Nor am I trying to be original per se or to indulge in personal fantasies or idiosyncrasies. Painting for me is the means to explore the possibilities and potentials inherent in form, color and space. My aim is to encourage the viewer to join me as an equal and active participant in the search for expression.”

During the 1970s and 80s the art historian Prof. Joseph Dreiss wrote several exhibition reviews that expressed a clear understanding of Ethe’s approach to painting. About Ethe’s first solo at the Marilyn Pearl Gallery in 1977 he wrote in ARTS magazine that “The primary formal issue with Ethe’s paintings is color: how to control it spatially and how to control it to control space; how to bring their utmost purity and piquancy, and how to orchestrate color in this heightened state.” The next year Ethe had another solo at the same gallery and Dreiss explained the artist’s deeper spiritual roots: “Solomon Ethe is a New York painter who for the last twenty years has worked quietly and carefully executing color abstractions of exceptional quality in the grand modernist tradition. The result is a body of work of great integrity and maturity that awaits discovery…Ethe’s colors are like musical chimes made visible. They express lucid and buoyant emotions…Ethe’s painting harks back to an older idea of the purpose of modern abstract art. Early pioneers such as Piet Mondrian, Vassily Kandinsky and Franz Kupka used abstract form as a vehicle to convey a metaphysical content. The spiritual was evoked as the justification and rationale for art without subject matter. American abstractionists have for the most part eschewed such explanations for their work, thus inadvertently calling attention to the materialist and predominantly secular basis of contemporary culture.”

Ethe’s moves to new studios were always one step ahead of the city’s gentrification and during the early 1980s he moved to a large loft space in Tribeca at Hudson Street. At a solo exhibition in 1984 he told Driess, “There are two impulses in me – one towards riotous sensuality, the other toward order and restraint.” Dreiss noted that the painter’s canvases were about “freedom and control, exuberance and stability, spontaneity and order” and that they were “lush, fluid, richly emotional, and deeply sensual statements about the evocative power of color.” He explained that his “original point of departure was the art of the American Synchromists Morgan Russell, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, and Patrick Henry Bruce. His earliest ambition as a painter, ‘to coax luminescence from pigments that would rival that of light rays,’ reflects this Synchromist influence and is still his most important aesthetic imperative.”(3)

In 1985 , Ethe moved to a studio at 14th St at Broadway looking out over Union Square. However, when a plumbing problem caused a flood that destroyed some paintings he put the bulk of his work in storage and instead worked on small collages at his apartment. The same problem struck again in the 1990s when water damage at the storage facility destroyed more paintings. In 2012, after living at 25 Fifth Avenue for 57 years, Ethe and his wife, Jane, moved from Greenwich Village to Chelsea where he continued to work on collages and small works. There he passed away in 2019 at the age of ninety-four.

Reflecting upon that moment in the early 1950s when Ethe became increasingly drawn to collecting works by modernist masters, one understands how his consciousness began to flow against the mechanical demands of his profession, rising like an incoming tide until he quit his fast-paced job in 1959. When he dropped his persona as a leading economic researcher, the analytical left side of his brain had given way to his artistic right side for good. The art historian Roger Lipsey observed that “Ethe seems to be working from a creative consciousness close in texture to the Zen mind. The value of voids, the cheerful surge of color, endless curiosity about surface and depth relations make these metaphysical paintings. They ask us to be simpler, lighter, emptier; and they are persuasive. They do not communicate a finished knowledge, but certainly a way of knowing.”(4)

— Peter Hastings Falk

Footnotes

1 Letter from De Hirsh Margules [1899–1965], 25 Dec 1963

2 Brown, Gordon (ARTS magazine, Jan. 1977, review of Solomon Ethe solo exhibition at Neill Gallery)

3 All three of the Dreiss quotes are from ARTS magazine, and the exhibition reviews are sequentially from Dec. 1977 and Dec. 1978 (both at Marilyn Pearl Gallery) and Nov. 1984 (at Steiger Jones Gallery)

4 Lipsey, Roger. “The Paintings of Solomon Ethe” (Parabola, 1977)

Museum Exhibitions

1974 Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art: 3rd Annual: “Contemporary Reflections” Ridgefield, CT

1968 Gallery of Modern Art (now the Museum of Arts & Design) “Dealers Choice” New York

1966 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 161st Annual, Philadelphia (No. 281: Untitled, 1964–65)

Gallery Exhibitions

2016 Carter Burden Gallery, 548 West 28th St, New York (solo: “Staccato” Oct, 2016)

2013 Carter Burden Gallery, 548 West 28th St, New York (solo, “Significant Form/Significant Space” Oct-Nov, 2013)

1989 Cathedral of St. John the Divine: “Analogues”, New York

1988 John Davis Gallery, New York (solo)

1987 Anita Shapolsky Gallery, 99 Spring St, New York (group, Feb.)

1984 Steiger Jones Gallery, 1015 Madison Ave., New York (solo, Nov.)

1984 Heidi Jones Gallery, New York (solo)

1984 Vox Populi, 511 East 6th St, New York (group, July)

1983 Vorpal Gallery, 465 West Broadway, New York (solo, Jan-Feb.)

1982 White Gallery, New York (solo)

1981 Landmark Gallery, 469 Broome St., New York (group, “Tenth Anniversary Show”

1978 Landmark Gallery, 469 Broome St., New York (group, Apr-May, “On the Edge of Color”

1977 Marilyn Pearl Gallery, 29 West 57th St., New York (solo, Dec.)

1977 Neill Gallery, 136 Greene St., New York (group, Dec.)

1977 Neill Gallery, 136 Greene St., New York (solo, Jan.)

1976 Buecker & Harpsichords, New York, 40 Years of American Collage, (group, Feb)

1975 Landmark Gallery, 469 Broome St., New York (group)

1975 Soho Center for Visual Artists, Prince St, New York (group)

1974 Hansen Galleries, SoHo, New York (solo)

1970 Star Turtle Gallery, New York (solo)

1967 Whitehouse Galleries Ltd, New York

1966 Rose Fried Gallery, New York

1966 A.M. Sachs Gallery, New York

1963 Gallery Gertrude Stein, New York (solo, Nov.)