— by Terence Falk, Curator of Photography

It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.

– Henry David Thoreau

Introduction

In the beginning of the history of photography, images were created by individuals immersed in scientific exploration. The results largely conveyed, “Look at what I can do.” As their craft became more refined, pivotal moments arrived when the message increasingly asserted, “This is what I have to say.”

There was no going back. The photographer and viewer have since become entwined in a unique reciprocal relationship of creator and viewer. Photographers make decisions, either consciously or not, which profoundly affect and even force the viewer to confront and react to what is in front of them. In turn, the viewer brings their own preconceptions or responses to the work — and it’s that interchange that fuels the life of the photograph.

One photographer that has masterfully articulated this relationship for over fifty years is Arthur Nager. With a combination of keen observation, humor, and an extraordinary sense of composition, his personal renditions of the human condition places him firmly in the pantheon of photographers such as Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, Tony Ray Jones, Harry Callahan, and Joel Sternfeld. Nager brings to the practice a uniquely personal take on what it means to be alive in all its complexities and he does so with an astonishing blend of wit, humanity, and vision.

The Elements Come Together

Arthur Nager was born in 1949 in Queens, New York. From an early age, the influences that formed him as a visual artist were in place, from his mother’s family and their insatiable sense of humor to his constant need to explore and understand music, history, art — all becoming part of his self-education and playing a critical role in forming him as a photographer. His father, a CPA, wanted his son to find something to land on to have a dependable career.

The Pivotal Moment

At twelve, Nager was fascinated with many different subjects, especially photography. He created a makeshift darkroom at home, recalling, “I was fascinated by the technology of photography. I set up a little darkroom, got a contact printer and started shooting with my Ciroflex, a 2-¼ x 2-¼ camera, which made larger contact sheet images.” When he was sixteen, he heard about an exhibition of a photographer he never heard of — Harry Callahan — at the newly created Hallmark Photography Gallery at 720 Fifth Avenue (left). It was a fateful experience, critical in shaping Nager’s destiny. “Callahan’s work was very important for me because it explored issues of composition, contrast, and various points of view,” he said, because combined with what seemed almost impossible to me — a kind of biographical, personal group of images — being an art form as well as documenting personal relationships. They were graphic, but they worked on multiple levels.”

The Right Place at the Right Time

The next stage in Nager’s journey came in 1966 with a full scholarship to University of Rochester. He was pursuing a degree in history and even thought of a career as a psychologist. After all, his father felt his son needed a “real” profession. However, his persistent curiosity in art motivated him to revisit his childhood interest in photography and he started taking history of photography classes with Beaumont Newhall [1908–1993]. Newhall was Director of the George Eastman Museum where he had built one of the largest photography collections in the world. He had earlier served as the first curator of photography at MoMA where his seminal The History of Photography (1937) was published. For Nager, this foundational experience proved nothing less than a watershed moment. During the next four years he would be introduced to the most important photographers, photo historians, and curators.

Nager’s first exposure to formal photographic practices came when he joined a photography group created by William Giles [1934–2025], founder of the university’s photography department (right). Up to this point, Nager was completely self-taught in photography. Yet he soon learned the zone system and the technical skills required to use a large format camera. Moreover, Giles was a disciple of Minor White, thereby exposing him to the concept of photography as a meditative experience and the creation of visual metaphors. Whereas Newhall exposed Nager to the history of photography and Giles plunged him into the making of photographs, both teachers were crucial catalysts in the formation of Nager’s personal voice as a visual artist.

In 1970, Nager received his B.A. and enjoyed his first exhibition at the university’s photography gallery. He then applied to the Masters Program at Visual Studies Workshop, under Nathan Lyons [1930–2016]. Looking back at Lyons’ decision to accept him into the program, Nager felt “Nathan found my application of interest not only based on the photographic work I had done up to that point, but also my background and degree in history which could lead to positions as a possible photo historian or for curatorial situations.” During Nager’s three years at the Visual Studies Workshop he was influenced by major photographers of the time. Robert Frank [1942–2018] taught filmmaking. Syl Labrot [1929–1977] also stood out as influential. “As my advisor in graduate school, Syl provided advice and support for the work I was doing at the time… He was supportive of the idea of looking at alternative approaches to the medium and being adventurous about the projects I was considering. Syl’s move to New York City really solidified our relationship…. He created beautiful large paintings, mostly abstract, and he was interested in the intersection of painting and photography. Syl was talented, worldly, sophisticated, and a genuinely sympathetic, great soul. And I felt very connected to him. His passing, which came suddenly, was tragic and a major event for me.” A fellow student with whom Nager became very close was Henry Wessel [1942–2018] who, like Nager, had contemplated a career in psychology. Wessel was one of ten photographers chosen for the highly influential 1975 exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of Man-Altered Landscape” at the George Eastman House. In 1971, when former George Eastman House curator Harold Jones became the first director of Light Gallery in New York City, Nager helped him install exhibitions when classes were not in session.

The Role as Educator

In 1968, photographers Cherie and Greg Hiser started the Center of the Eye Photography Workshops in Aspen, Colorado (above). Cherie Hiser [1939–2018] excelled at cultivating academic relationships with other educators such as Nathon Lyons at the Visual Studies Workshop. It was this fateful connection in which Lyons recommended Nager, now a graduate student, to teach at the Center of the Eye in 1971-73. (During their last year, graduate students were required to leave school and spend time in the world working). Along with Nager, photographers such as Arnold Gassan, Lee Friedlander, Paul Caponigro, Bruce Davidson, and Cornell Capa taught at the workshop.

In 1972, Nager received teacher certification and became head of the photography departments at the Aurora Public Schools system in Aurora, Colorado. In 1973, he became Chair of the Photography Department at University of Bridgeport, in Connecticut. Nager recalled, “I was lucky enough to have taught in both the workshops as well as public schools. You must deal with all kinds of circumstances. I had to not only teach at the University of Bridgeport but literally had to build its program. It was a leap of faith to some extent, that photography provided opportunities to incorporate all the things I had done. I was interested in history, teaching, and I loved photography. I saw this as a chance to incorporate all the things that lead up to this point.” During his tenure at the university Nager received two research grants in support of ongoing projects that lead to solo exhibitions. While at the university, Nager served as a visiting lecturer and artist at numerous art schools including Trinity College, Southern Illinois University, and the Nova Scotia College of Art.

Coincidentally, in 1973 this author was also accepted into Nager’s newly created photography program at the university. He was my first photography instructor, and I witnessed his incredible ability to create a diverse, intensive program including an extensive curriculum of study. Additionally, he enriched the program by creating a Masters of Photography lecture series, hosting luminaries such as Frederick Sommer, Arnold Newman, Ralph Gibson, Roman Vishniac, Lotte Jacobi and Mary Ellen Mark — exposing the students to masters of the medium. It was a transformative experience for me which I will never forget. My personal experience there confirmed that Arthur Nager surpassed his goals!

Finding His Own Voice

Although Nager’s early work was influenced by the noted street photographers of the time including Harry Callahan, Robert Frank, Gary Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander he realized it was vital to express his own unique voice. In an interview with Rupert Jenkins, author of forthcoming book, Outside Influence: Photography in Colorado 1945-1995, Nager reflected on this issue, “I imagine that most photographers working in the seventies were aware and often influenced by what they were seeing at the time, and I’m no exception. Part of the dilemma for any photographer is recognizing how they are influenced by other photographers while working to establish a personal point of view. I didn’t want to become another Garry Winogrand or Hank Wessel, but what I appreciate about the medium is the diversity and options available when making photographs. It’s important to understand what other photographers are doing, but the challenge is figuring out how to chart one’s own creative path.”

In Santa Cruz, California (above, 1975) a young couple casts pensive gazes toward the photographer, unsure of his intentions. The small gesture of the girl’s hand on her boyfriend’s waist confirms their relationship and her trepidation. A row of arcade machines behind them leads to a boy who, in turn, gazes at the couple.

Nager takes on the issue of many different types of people in compressed scenes such as Las Vegas, Nevada (above, 1975). There are no conversations on this bus, and only one implied relationship. Everyone is hiding behind sunglasses except the forlorn boy near the window. Is he the only one clearly seeing the lack of human connections? The man standing at right foreground, closest to Nager, gazes at him, likely pondering the purpose for recording this assortment of people. Even the couple seated at left seem unsure of where things are going.

The three quintessential ingredients to Nager’s personal photographic vision were coalescing: humor, surrealism, and graphic composition. These elements work in harmony. Unlike the dramatically beautiful yet sometimes acerbic vision of Robert Frank’s vision of Americans, Nager is not judging his subjects but celebrating their uniqueness with humor. Winogrand’s depictions of everyday American life are an influence, but Nager goes further to share the absurd situations of our lives without harsh judgement, but insightful inclusion.

Colorado Fair (above, 1972) is simply a myriad of contradictions. Nager observed, “Here’s this guy with his handmade signs.” He then quickly asks, “If you were looking for more income, would you ever ask someone to handle your finances with such an unprofessional lack of awareness?” He then answers his own question, “This is basically a documentation of human frailty and naïveté.”

Sometimes, the simplicity of a Nager image can be simultaneously comical and surreal. In Secretary With Mounted Shark (above, 1971) a secretary on the phone glances at Nager as a huge shark looms over her head. It’s as simple as that, but what in the world is going on? Why is the shark there? The woman seems oblivious to the potent symbol of danger. By engaging with the photographer, she ultimately engages with us, the viewers. The otherwise blank wall further simplifies the scene and serves as the ocean itself. Nager explains, “I came into this office and realized the juxtaposition of this huge shark and this woman trying to do her job correctly. Compositionally, three quarters of the photograph is about the shark, and then there is the contradiction between this nautical creature and a woman in a banal 1950s era office setting that creates a tension.”

Surrealism reigns in Bridgeport, Connecticut (above, 1973) Nager’s composes the shot with two vertical sections which strengthens the image and the white lights on the window edge mimic the eye patch. The mannequin is stealing the show. This is not a costume shop, its formal wear. Why on earth would the child mannequin wear an eye patch? Good photographs ask more questions than provide answers. Nager presents a dream with no escape, no answers. It simply is, and it is there for us to wonder. In my interview with Nager, he reflects on other art mediums and his decision to pursue photography, “I did try collage at Visual Studies Workshop, but I realized I am much better as an extractor, deciding what to include and what to eliminate instead of starting with a blank canvas and deciding what to put into it.”

Nager’s instinct for using the camera’s ability to flatten a scene, bringing all the elements together in the same plane, is illustrated in Downtown Denver, Colorado, (above, 1972). The results are as complex as a Cartier-Bresson photograph and a simple as a George Braque collage. Nager fuses everything together, from his use of the intense sunlight to the pedestrians merging. As the Black woman at dead center steps forward she confronts the photographer directly but is bookended by white people — perhaps representing issues of race in America. In this strong light and shadow, all faces appear stylized and flattened, almost Picasso-esque, while raising a sense of social drama. Implications overlap and abound, as if they are not just luck but innate to Nager’s working method. “I still do this,” he explained, “I will wait at a cross walk and wait for people to come across the street, especially with my current color work the way they are illuminated and in their relative positions in the frame.”

The New Topographics Work

Nager’s innovative approach to seeing, which began in the early 1970s, also shows a highly sensitive ability to document a sense of place. Even at present, his series of topographic works continue to make this clear. Historically, the New Topographic movement in photography can be traced back to the 1950s with the work of Bernt and Hilla Becher [German, 1931-2007 and 1934-2015], who obsessively documented industrial sites throughout Europe. A groundbreaking exhibition at The George Eastman House in 1975 entitled “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man Altered Landscape” featured the work of ten photographers, including Nager’s friend Henry Wessel, plus Frank Golke, Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, and the Bechers. The exhibition was a radical response to the accepted view of where we live and how we regard the land in America. Rejected were the romanticized landscapes of Ansel Adams or the meditations of Edward Weston. Photographers of the New Topographics movement forced Americans to see how they really treated the land, and they did so with photographically blunt force.

Nager’s response to the New Topographics movement was tempered by the need to create something that also stood on its own as a personal humanistic expression. While he continued to be inspired by the movement he was striving to develop a unique personal vision. Essentially, he was balancing the humanistic photographs of Harry Callahan with tightly structured paintings such as those by Josef Albers.

This scene is simultaneously confronting but not judgmental. Nager is empathetic to the inhabitants than other photographers at the time. He revels in the discovery of a place. The scene could be part of a dream. The owners of these places are celebrated instead of being judged.

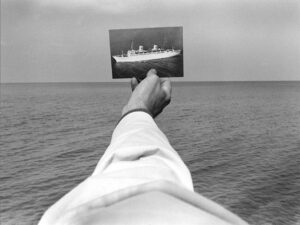

One can immediately reference the work of iconic conceptual photographer Kenneth Josephson [b.1932] (above), whose purpose for examining the role of photographs in our lives, and our perceptions of reality, is groundbreaking. In two of Nager’s works — the earlier Aurora, Colorado (1972) and the more recent color work High Line, New York (both below) — we see how Nager not only continued this passion for a sense of place. Shot decades apart, both images are clear examples of a mastery of vision. Both are photographs of photographs.

In Nager’s photograph above we see an interior with another photograph of an idyllic landscape surrounded by a lifeless interior. A set of TV rabbit ear antennas pierce the image in half. Questions abound in the ridiculous scene in front of us. Is a television, out of camera view, enjoying the photograph of nature? Has it become the viewer instead of being viewed? Or perhaps Nager is suggesting that the images we are bombarded with, either still photographs or television screens, are just illusions. This bizarre comedy cannot be ignored. The simplicity of the scene is absolute and necessary for its success. Nager commented on this photograph, “You’re touching on one important thing I’ve always found that refers to my photographs which is the implied narrative. Looking at a picture forces the viewer to make an interpretation of what is actually going on and that interpretation has a lot to do with the viewer themselves… I include people and situations that seem to suggest a story but it’s not clear what that is, and now the viewers perspective enters.”

In Highline, New York City (2010), we see an almost parallel scene, albeit outside. We are now the spectator, instead of the television suggested in the previous photograph. The distant horizon is anchored by the density and complexity of buildings in Manhattan, yet at the very center is a mammoth photograph of a perfect mountain view. The disparity of this idyllic landscape crammed into the reality of urban life is hysterical and somewhat sobering. What is it doing there? Does it represent the unspoiled virgin landscape, now unrecognizable, that was Manhattan so long ago? Is this what we lost?

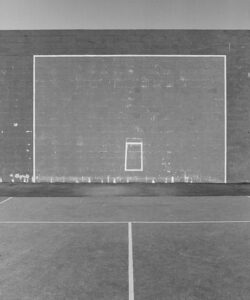

Nager’s topographic work — the early black & whites as well as the more recent color images — clearly reveal the influence of Joseph Albers. This early photograph, Handball Court No. 1 (left, 1974) could easily be framed as a horizontal, but Nager instead applies a vertical format that competes with, yet complements, the large horizontal rectangle painted on the wall. Note how the camera lens flattens reality by connecting the white lines on the ground to the white lines on the wall.

Nager expands on the issue of composition, “I think of myself as a formalist. My sense of compositional awareness of the graphic elements in a picture, whether it’s squares or something else, has always been a crucial issue in how I compose pictures.” Nantucket, 2019 (above) summons Albers but its white wall offers no escape. The only option is through the opening in the center, which offers beautiful sky, sand dunes and grasses in the distance, but there is no guarantee we can get there. Comparing this topographic with Eleuthera (below, 2019) one notes two very different portals.

In Eleuthera, Nager presents a readable environment easier to comprehend. At first, we freely wander and explore. However, the confrontational central blue structure beckons us to investigate. It seems to offer the remnants of another building, or another life. Nature is now reclaiming its place regardless of man, and we may not be welcomed into that blue surround.

The Coalescence of Topographic and Street Photography

Nager’s more recent color work continues his coalescence of humor, graphic simplicity, and an acute sense of space. In Dog Picnic (above), an overhead viewpoint invites intimacy from the viewer and at the same time underscores the simplicity of the composition. A couple lie on a blanket (another square element, within which are repeated squares) protecting them from the hot beach sand. Not one part of their bodies touches the sand. Their dog sits patiently at the upper left, allowed to suffer. There is no room on the blanket for him. This bizarre contradiction of wanting a pet in one’s life but remaining oblivious to their plight renders a dark comedic quality. The faces are turned away in a gesture of anonymity or indifference.

Times Square, New York (above) shifts to a distinctly different image that is visually and socially dense. Nager explained his creative process: “When I photograph in places like Time Square, I never know what combination of people and circumstances are going to come together to create the play I might be able to capture. What happened in a lot of cases was I could see the potential for a coming together of all the elements. In this case it was fortuitous because of the pathos of the little dog.” Centered in the photograph is Elmo, in blazing red. A tip bag seems pathetic as it hangs from his waist, hoping for a handout. Elmo holds a tourist’s dog for a photograph. His hypnotic gaze and the dog’s wariness confirms the absurdity of what is unfolding. At left, an excited family enters the frame, healthy and happy. At right, after Elmo, the couple reflects the opposite of the family’s smiles. The old man struggles with a walker, while the woman escorting him looks concerned. There is no joy in their experience here. The poor dog in Elmo’s arms echoes the worry of the woman on the right side. This jammed-packed assortment of characters is an empathetic yet humorous look at what we value and what we will endure to find it.

Lower East Side, New York City (above, 2019) departs from the classically accepted “topographic photography” because it is imbued with Nager’s signature combination of color and humor. Two chained mannequins are brightly attired, yet there is no hope of escaping to fulfill some destiny — even the little dog on the right has more freedom.

Aerial Ride, Santa Cruz (above 2011) is a signature Nager photograph, with great attention to graphic composition, use of color, camera angle, and, of course, the absurdity of the result. For a second, do we not notice the character in the front chair is a sculpture of a goofy caveman? This is a gentle jab at American culture. Nager sees us as passengers (and maybe even as viewers) who gladly accept that fiction may ride along with us. Clearly Nager revels in celebrating our country in all its humorous variations.

Tattoo Rider, Santa Cruz (2011) is arguably one of Nager’s finest works. According to Nager this image is “so filled to a saturation solution. There’s something very poignant about the guy holding onto the pole.” In this image vertical lines confuse but unite. The eye desperately searches for something on which to land. We have choices: the woman on the left, the woman on the right, or the man in the center. We inevitably settle on the man at center. Now the questions start. Why is a grown man riding on a carousel? His tattoo-covered body is itself a visual reflection of the myriad decorations in the amusement ride. Since his face turned away, we could create in our minds scenarios either innocent or menacing. The result is an invitation into another dream. We, the viewers, must decide.

Toward the end of my visit with Nager, he concluded our conversation by saying, “You know, what really captured my sense of wonder, irony, and even amazement is how weird things can appear when they are captured in a frame. That’s what I would like to communicate through my pictures.”

![]()

Museums, Exhibitions, and Publications

Collections: The George Eastman House (N.Y.), South Street Seaport Museum (N.Y.), The Brick Store Museum (Kennebunk, Maine), and the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History (Calif.).

Exhibitions: “Building Stories,” a solo exhibition at the Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Conn. (2025); Acta International Gallery, “The Colorado Photographs, 1972” (2023); the Slater Memorial Museum (Norwich, Conn.), Lake Placid Center for the Arts, Texas Tech University, Housatonic Museum of Art (Bridgeport, Conn.), Carriage Barn Arts Center, (New Canaan, Conn.), (Praxis Gallery, Minneapolis), Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, Mass.), Umbrella Arts Center (Concord, New Hampshire), and the Ilon Art Gallery, New York.

Literature: Il Fotografo — “Arthur Nager, Street Photography” (2023); “Divine Light Photographs” in Rupert Jenkins’ Colorado Photo History blog (2022); Wrestling at Sunnyside Garden Arena — by Arthur Nager (with Introduction by Jonathan Panes and Mike Silver, 2021); Central Park Photographs — by Arthur Nager (with Introduction by Bruce Glaser) 2018; L’Oeil de la Photographie — “Central Park Photographs” by Arthur Nager (2018) ; “Times Square Photographs” — Exhibition catalogue of photographs by Arthur Nager (2017); The Photographers Cook Book — George Eastman House, 1970s (reprinted 1990)