Blodgett: Deep Diving into the Unconscious

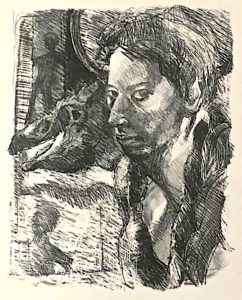

One of the most extraordinary rediscoveries in American art in decades is now running through the month of October at the Karin Clarke Gallery. This exhibition does more than justify Tom Blodgett’s claim that he was “the van Gogh in America.” His masterfully executed large “painting-drawings” were selected from his estate collection by artist-curator Craig Spilman, who noted that “He’s one of about three artists I can think of in my lifetime that actually did work powerful enough to bring me to tears.”

The exhibition “Faces, Figures, and Phantoms — A Partial Self-Portrait” brings to light the authenticity of a truly unique vision steeped in spiritualism. But Blodgett’s spiritualism is not saturated by Pollyanna notions. Rather, these works are the results of his deep dives into the realms of the unconscious, journeys he found both exhausting and exhilarating. He brought back images of intense imagination executed with technical brilliance. These often-jolting works relate to Surrealism — and at the same time expose that the biggest problem facing most contemporary artists is that they no longer believe that art has much to do with experiencing the spiritual. Many art historians have also avoided discussing how the unconscious planes are the source of compelling images that, translated by a master, can awaken our capacity for recognizing the spiritual.

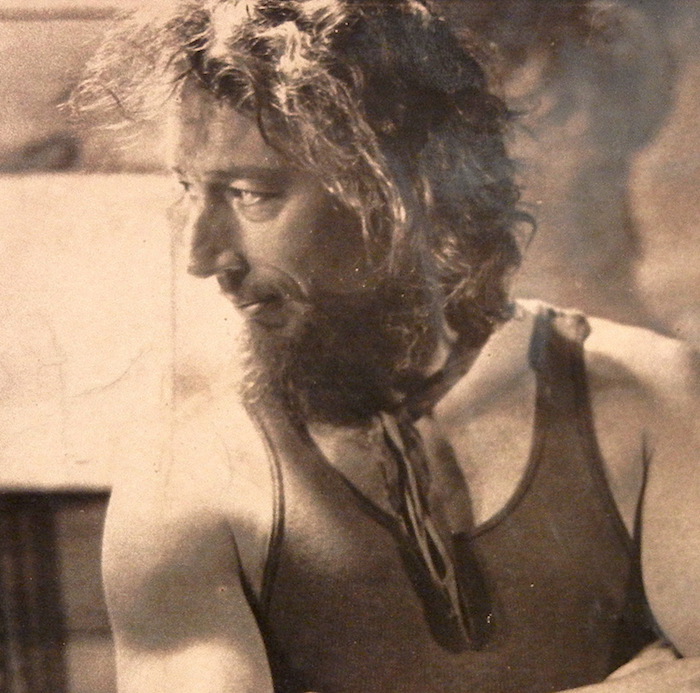

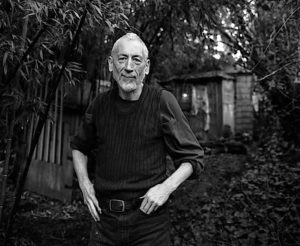

Blodgett identified his own death as the catalyst for his inner necessity to explore the spiritual. In 1950 he flatlined (at ten years old) and was miraculously resurrected. Thereafter, he embarked on an artistic quest, and as he matured resisted materialism while striving for transcendence. Proof lay in his abode in the hills of Eugene, Oregon, which he called “the shack in the jungle.” It was engulfed in an evergreen jungle of bamboo rising forty feet high, a barricade made even more dense by blackberry brambles half as tall — rendering it completely hidden from view. There was no running water. His toilet was a pit he had dug outside and into which he would regularly shovel ash. The furnace was often broken so his only dependable source of heat came from a large fireplace.Blodgett was confident that his work merited being in the Met in New York. However, he felt deeply betrayed by what he saw as an insular art scene, not only in Eugene but around the country. How could his art be shunned — even repudiated — if his art expressed a deeply meaningful and transformative vision? He quit his college teaching position and insulated himself in his shack. A group of student followers were attracted by his charisma and challenge. He urged them to experience an inner life essential to the creative process as opposed to the theories and conceptualism presented in the outer world. The press called his group a cult.

In an article in the Eugene Weekly, Bob Keefer described Blodgett as “an archetypal eccentric genius,” adding that “Blodgett’s drawings are exquisite — finely observed, deftly captured, perfectly expressive, without a trace of doubt or hesitation in his hand. He was as confident with a pencil or charcoal stick as Picasso.”

Blodgett’s extensive diaries show that he was in accord with a term coined by art historian Donald Kuspit — “mediafication” — to describe the relentless materialization of contemporary art. “There are no doubt works that seem emotionally powerful, and even deep,” wrote Kuspit, “but rarely does one find a work in which the emotion and the medium seem one and the same.” This description fits Blodgett’s work. In exposing the depths of his inner life, Blodgett shared a new vision of reality that was innocent, honest, and steeped in the spiritual. Morris Graves and Mark Tobey have for generations been considered the greatest mystic painters of the Northwest. Now Tom Blodgett joins that pantheon.