Wayne Ensrud grew up in Luverne, Minnesota, a tiny prairie town in the southwestern part of the state near South Dakota. Grazing just outside of town are herds of bison, on prairie that was home to the native Dakota Sioux. Nearby is the tiny Blue Mound Wayside Chapel, which seats just eight. The boy never appeared destined to become an artist. During what was a tumultuous childhood, he had spent his summers since the age of twelve on various labor jobs. First he was a ditch digger on the local roads. Later, he worked in a steel mill and a cement plant. And as soon as he got his driver’s license he drove a truck to pick up eggs and milk from the local farms. Art was far from his mind. His primary art appreciation was for the skillful custom pin-striping he observed being painted on the trucks.

With his powerful Norwegian physique, Ensrud dreamed of become a professional football player. That dream evaporated after a career-ending injury in high school. Fortunately, it was in the home of his first girlfriend that he appreciated the watercolors of her mother, who had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. This led him to experiment with a drawing class at the Carnegie Library, run by Mary Renfro, wife of the owner of “Renfro’s 5 & 10 Cent” store. The experience encouraged him to produce some drawings for his high school paper and yearbook. But it was hardly a foundation to become a serious artist. Nevertheless, after this most brief of encounters with art, Ensrud was determined to attend the Minneapolis School of Art (now the Minneapolis College of Art and Design).

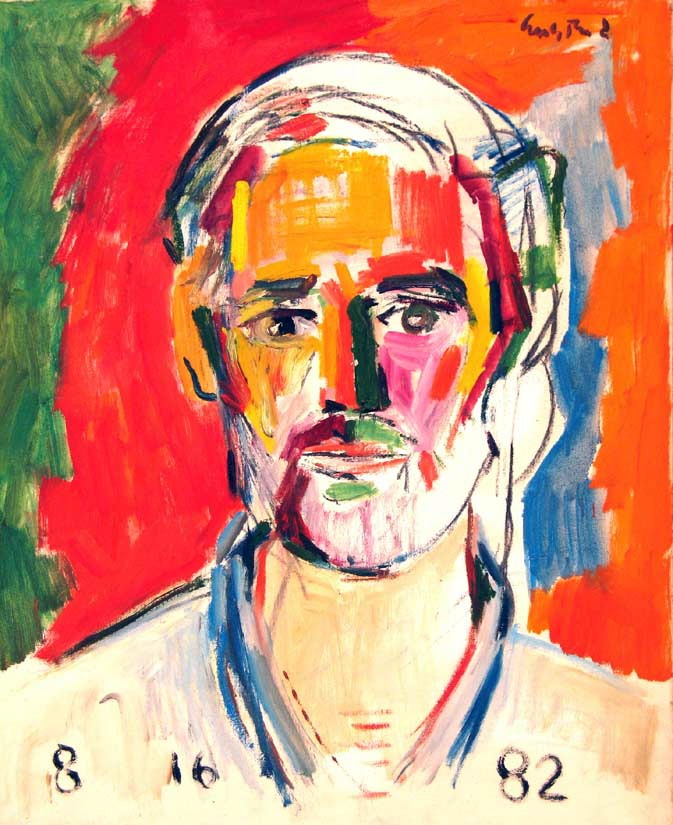

During Ensrud’s first year at the Minneapolis School of Art, in November and December of 1952, Oskar Kokoschka served as the guest lecturer for the school’s “Artist and Society” series. Art historians are typically surprised to learn that Kokoschka made several extended visits to the school. In fact, he spent far more time in Minnesota than any other place he visited in America. Ensrud, an eighteen-year-old who had never heard of Kokoschka, suddenly found himself in rapt attention as the master delivered his talks. Although Ensrud had been prepared to hear another dry academic treatise, he was quickly captured by a master who rejected the analytical in favor of a highly personal approach. Kokoschka saw himself as a catalyst for making the act of seeing a powerful emotional experience, which he expressed in the German existential concept of “erlebnis.” For the first time, the young student heard someone speak enthusiastically of a life in art offering experiences that were at once visual and spiritual, exciting and profound… experiences that would lead to not only to a highly-individualized form of expression but to true self-discovery.

Kokoschka’s two-month symposium left an impression upon Ensrud that was profound and lasting. He even took a job in the school’s lunchroom so that he could sit and talk further with the master. In the years that followed he had lasting discussions with other guest teachers such as Myer Shapiro, Buckminster Fuller, Josef Albers, Jacques Lipchitz, and Jacques Barzun; and he become particularly friendly with Ben Shahn.

After Kokoschka’s departure, Ensrud continued his original course objective in graphic design, and landed an after-school job as a letterer for a sign-making company. He even designed a machine to print on three-dimensional objects, such as vending machines. By his senior year he was working as an illustrator for the Minneapolis Star & Tribune. Still, it was Kokoschka’s philosophy and paintings that continued to haunt him, and by his senior year, in 1956, he was certain he wanted to break from illustration and become a painter. After graduation, he even returned to attended Kokoschka’s second series of lectures, in the fall of 1957.

Armed with even more determination to become a painter, he accepted the invitation of one of his college instructors, Julia Pearl, to move to California’s Bay Area. Here he lived with Pearl and her husband, Ivan Magdrakoff, also an artist. Ensrud’s senior year was to have been primarily under the tutelage of Pearl, but because she departed for California a year earlier, he was left to his own explorations, a virtual independent study. “I was possibly the first student at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design ever to receive my degree by essentially being allowed to have my own studio space,” remarks Ensrud. “Maybe this fortuitous event explains the reason for my individualism and independent attitude.”

In Berkeley, Ensrud soon became immersed in the art library of the University of California, where he discovered more about the lives and works of Kokoschka as well as Egon Schiele and his other heroes, such as Paul Klee and Josef Albers. This was also a prolific period of drawing and painting of the figure. Necessity, however, called for him to accept a position at the University of California at Berkeley as a graphic designer and Art Director of Motion Pictures and Television for all nine campuses. In 1960, his film, “Computers and the Mind of Man” won several awards.

In 1961, Ensrud’s first trip to Europe’s museums further solidified his ultimate goal of becoming a painter. Upon returning to New York, friends steered him to acting, and he appeared in six off-Broadway plays. The actor Kirk Douglas was sufficiently impressed to offer him a screen test. Instead, he took a one-year stint as the art director for Channel 13 WNET New York where he changed the look of public television from dour to dynamic.

Throughout this series of practical jobs, Ensrud continued painting until he reached a point when, in 1963, he felt compelled to seek out Kokoschka in Switzerland. Although Kokoschka had founded his School of Seeing in Salzburg in 1953, Ensrud had no intention of attending as student. Despite success in film and television, he remained unfulfilled as a painter. His quest was deeper. The reunion with Kokoschka was emotionally charged. “For ten years, Kokoschka had been on my mind. Owing to the books in Berkeley’s art library, and my absorption of the art in European museums, my painting had begun to make more sense to me. But I was lacking that complete immersion, that confidence to make the final leap. Suddenly, I found myself before Kokoschka in a moment of complete capitulation, and broke down crying. He understood immediately. He had such empathy that he began crying too!”

Ensrud’s commitment to painting was not the result of a gradual evolution. Rather, it was an epiphany experienced with Kokoschka. From this point on, he would make extended visits with the master every year, who accepted him as if he was an adopted son.

Back in New York, Ensrud continued to paint while also teaching film animation at the Pratt Institute from 1968 through 1971. After that final teaching stint, he dedicated his time completely to painting. “That reunion with Kokoschka in 1963 was a turning point,” says Ensrud. “After that point I was driven to paint. All I did was draw, draw, draw.” On my annual stays with Kokoschka, he did all the talking, and I listened.” From Kokoschka, Ensrud had come to understand that painting was a metaphysical act, charged by the spirit. Kokoschka would caution his protégé, “You shouldn’t paint unless the spirit moves you. And when it does, drop down on your knees and give thanks!”

Ensrud may well be considered Kokoschka’s living legacy, for he inspired him to dig deeper than other young contemporary artists, most of whom had been misled into thinking that a focus of massive energy and emotion were enough to become a great painter. Soon, the master’s protégé had become empowered with a sensibility of treating colors like musical instruments, cycling through every instrument in the musical score, from flute to bassoon. Ever since, Ensrud has layered and opposed his colors, instinctively controlling the movements they can impart; and, like tasting fine wine, their rhythm inevitably flows forth. “It’s not intellectual,” he says, “I’m not an epic painter. I’m a lyric painter.” And therein lays the great difference between Ensrud and many contemporary artists who pursue conceptualism. Ask Ensrud what he is thinking when he paints, and he’ll tell you to first get rid of the word, “think.” “I go in blank,” he says, “I have an objective and a feeling, but there is no plan.” Rhythm is critical to Ensrud. As one flowing with the music, he is attuned to chance strokes. Gradually, the image reveals itself.

Ensrud speaks and writes eloquently about his philosophy and his art, lulling one into feeling they are speaking directly with Kokoschka himself: “There is a rhythmical arrangement to the dance,” says Ensrud. “It’s not that I’m so interested in space itself. Rather, I’m interested in pulsation. That’s what keeps me painting. Otherwise, the painting would become just another variation of what others have already done. The point is to bring a dead piece of canvas to life. All living matter pulsates, but most people can’t see it. Kokoschka saw life pulsating in the landscape as well as in people. He made me realize that I had an important job to do. And that’s to remain true to capturing this indefinable magical quality. In painting portraits, too, I just try to get out of the way and let the sitter emanate. In this way I mirror the psychic dance between myself and the sitter. In the end, it’s about music, and not one’s objective recognition of the subject.”

Like Kokoschka, Ensrud is not a draftsman-painter but a painter’s painter. That is, he is a classic Expressionist who, owing to his total absorption in the subject and the moment, reacts quickly and intuitively as he attacks the canvas. He instinctively draws with a staccato line and paints with a bravura brushstroke. He especially acknowledges that another key to success came when he fully grasped Kokoschka’s concept of how color could generate a push-and-pull power between background and foreground. On his extended stays in Austria, Ensrud would become energized by Kokoschka’s enthusiasm over the numerous landscapes and cityscapes, which Ensrud often painted from the roof of his hotel. He recalled a visit when Kokoschka, upon seeing one of Ensrud’s views of Salzburg, exclaimed, “I wish to God I had painted that!” On another visit, Kokoschka was so moved by one of Ensrud’s pastel portraits of a Belgian girlfriend that he demanded she sit for him, too, exclaiming, “I must paint her portrait!”

“In its highest workings intuition becomes inspiration that reveals great fundamental truths and supreme mysteries,” says Ensrud. “A door is opened to the most sublime inspirations regarding the supreme truths of the universe. The intuition grasps ideas from the mysterious Infinite Mind and presents them to the imagination in its essence rather than in a definite form, and then our image-building faculty gives it a clear and definite form which it presents before the mental vision which we then vivify with life by letting our thought dwell upon it, thus infusing our own personality.”

While Ensrud realizes that his great fortune is a Nordic temperament that falls squarely in the joyous realm, he is highly guarded not to be fooled into making paintings that are simply visually pleasing. After all, he says, “That’s my inner tempo being manifested on the canvas.” Thankfully, here is art with sureness and unflinching honesty in every stroke. Ensrud’s kind of music continues to be a living testament to one of the twentieth century’s greatest Expressionist masters, Oskar Kokoschka.

Erotica: Ensrud's Experience of Aesthetic Ecstasy

-

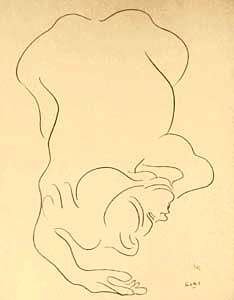

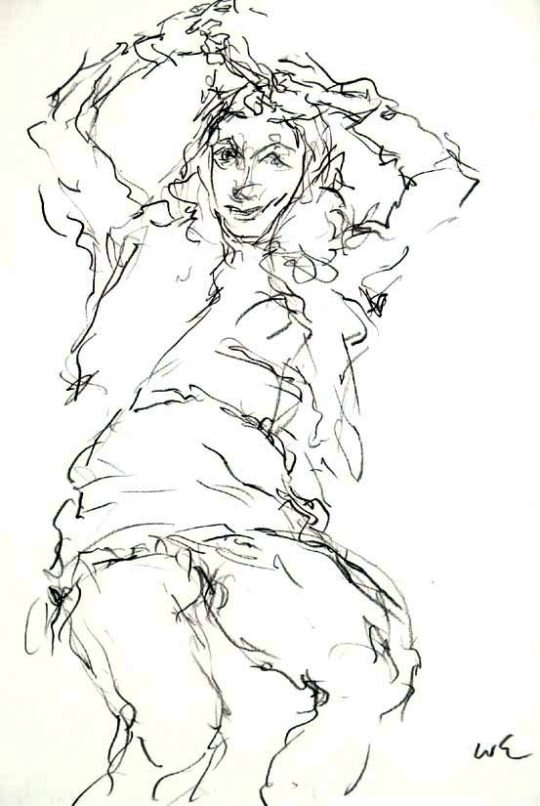

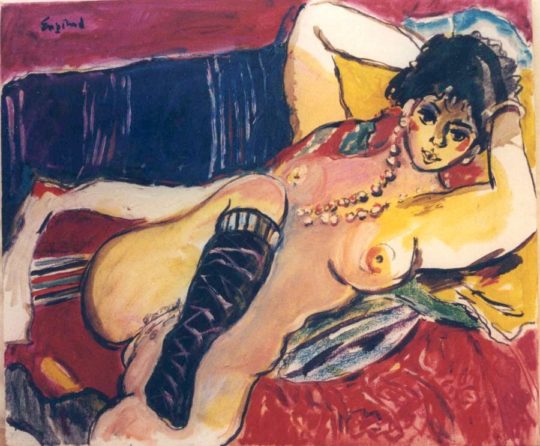

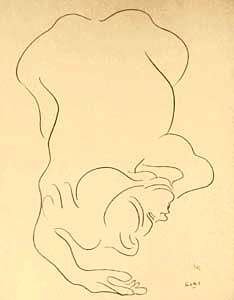

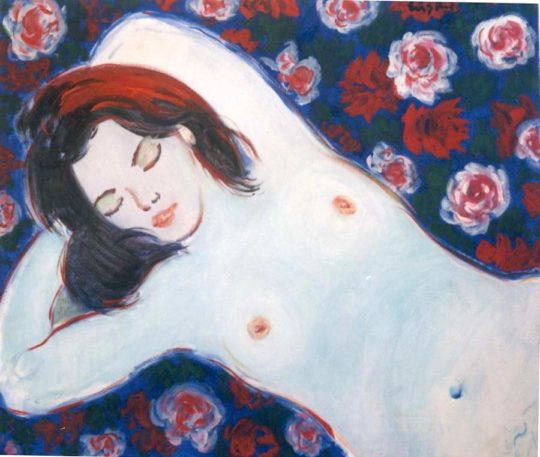

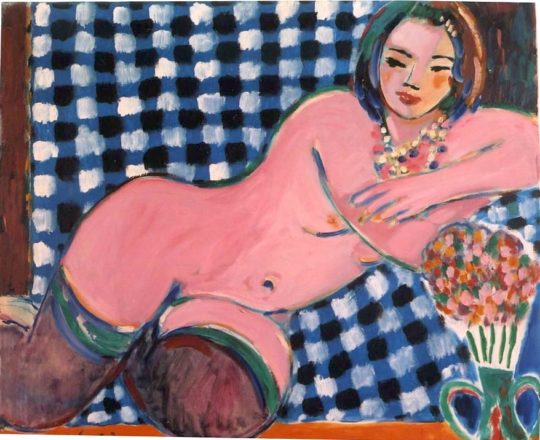

A Young Woman, 1985

22 x 28 inches (55.88 x 71.12 cm) -

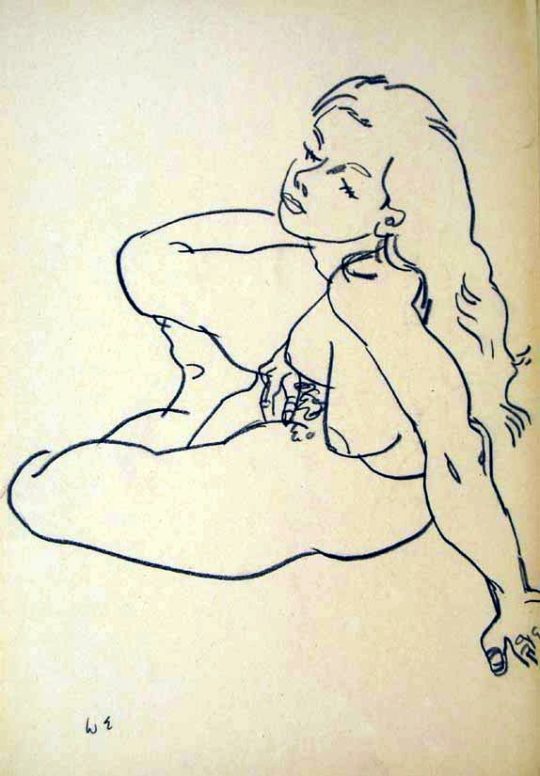

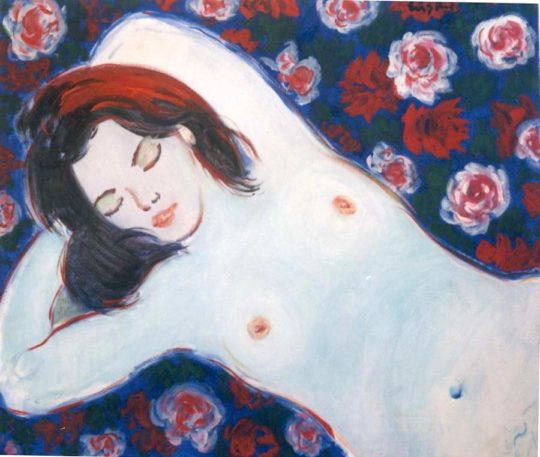

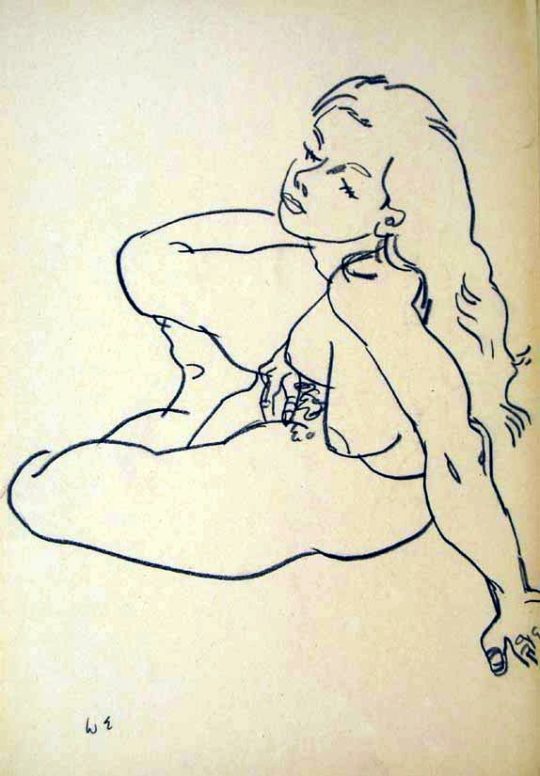

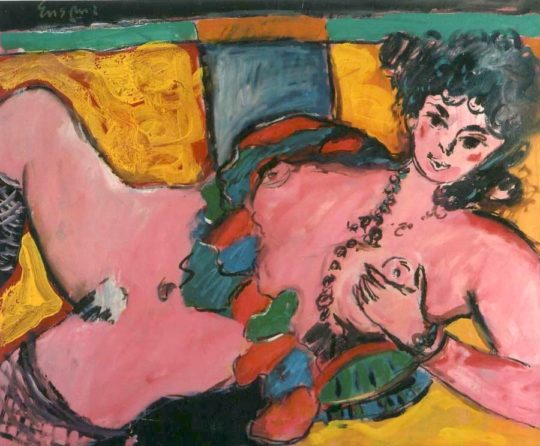

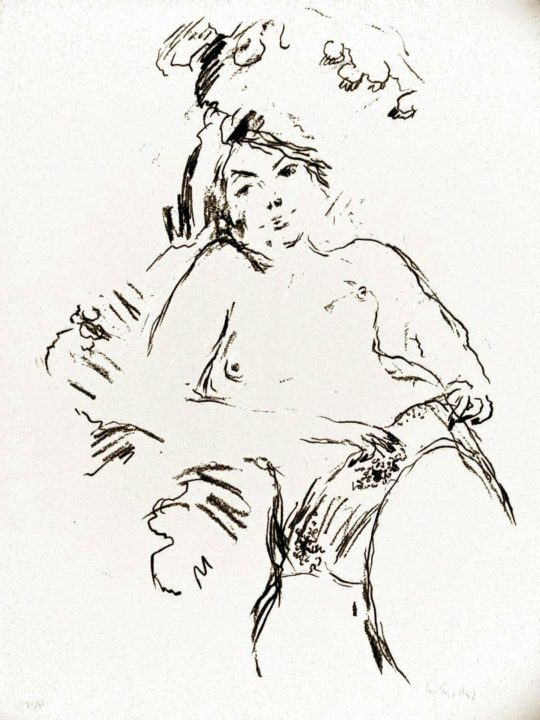

Crouching Nude, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

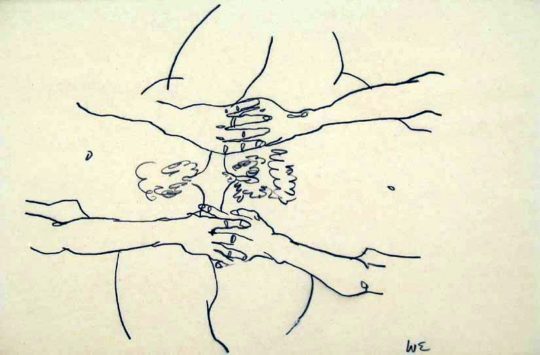

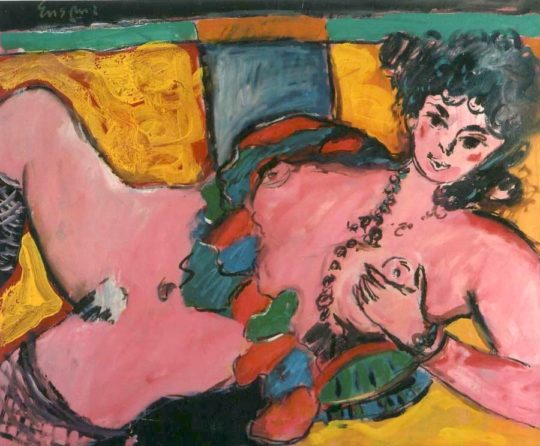

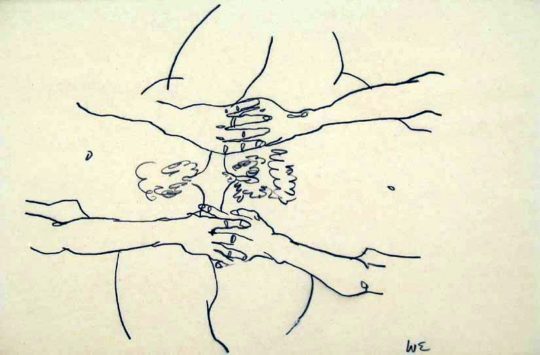

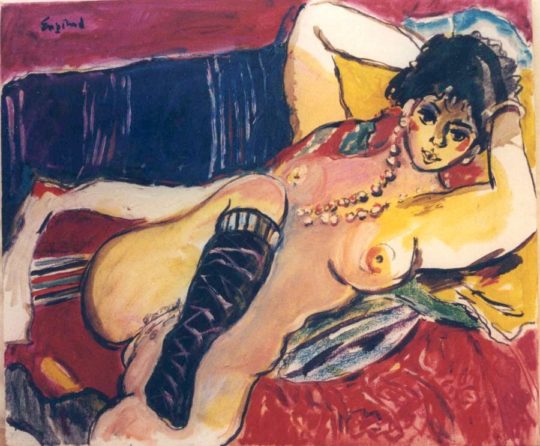

Erotica No.19, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

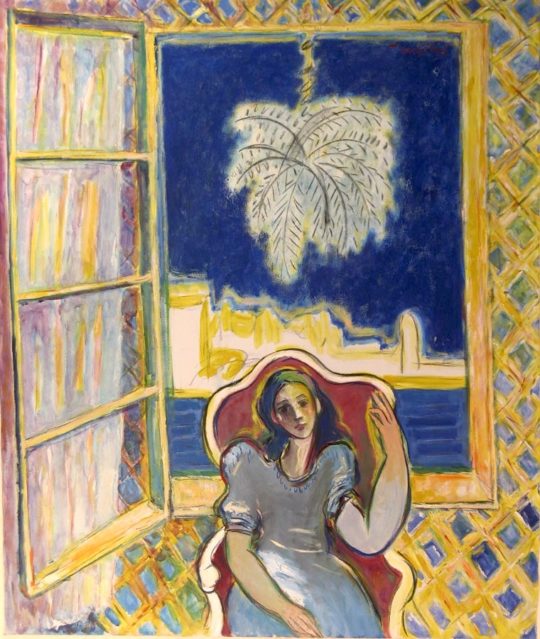

Erotica No.4, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Erotica No.41, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Erotica No.45, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

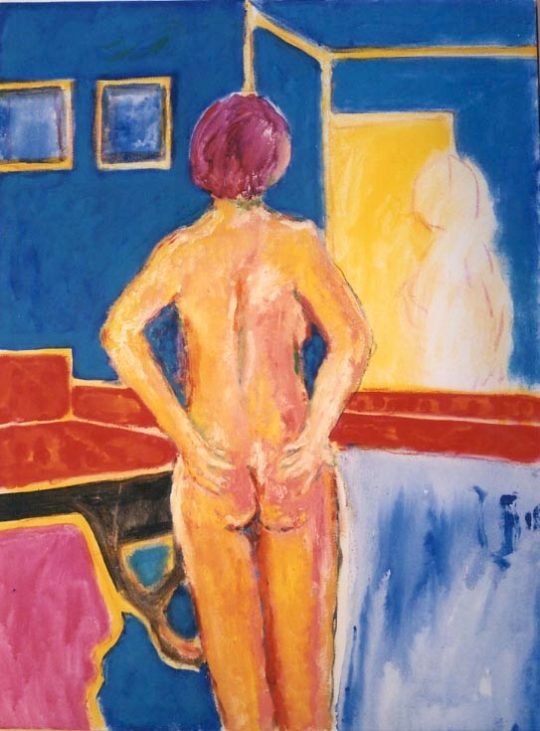

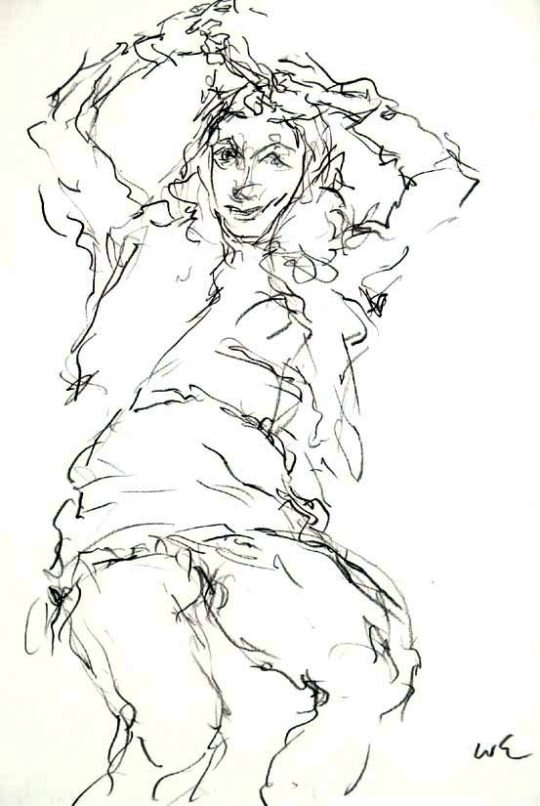

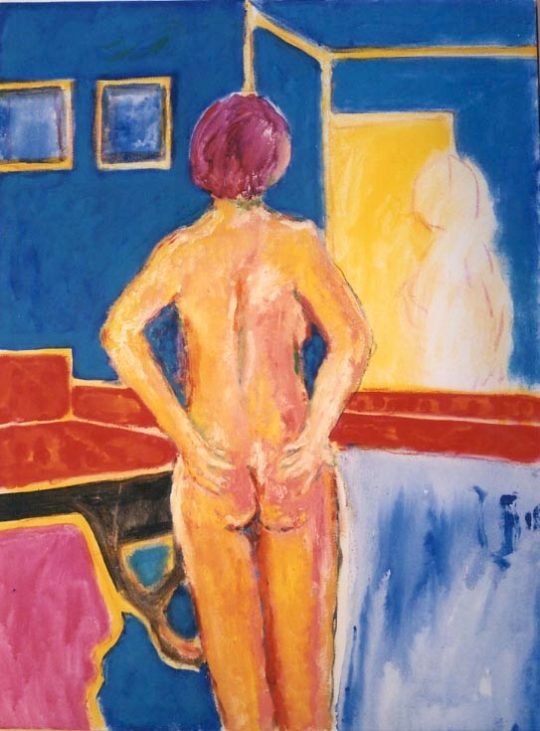

Figure No.1, 1993

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

Figure No.11, 1995

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

Figure No.12, 1990

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

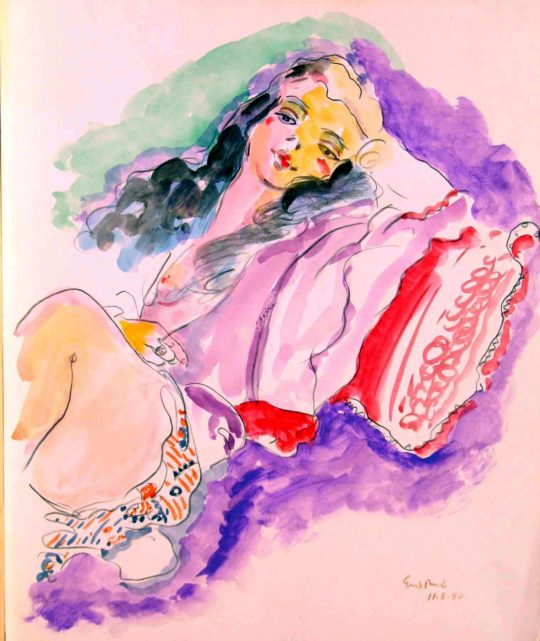

Figure No.14, 1985

30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 60.96 cm) -

Figure No.26, 1985

36 x 46 inches (91.44 x 116.84 cm) -

Figure No.28, 1985

36 x 42 inches (91.44 x 106.68 cm) -

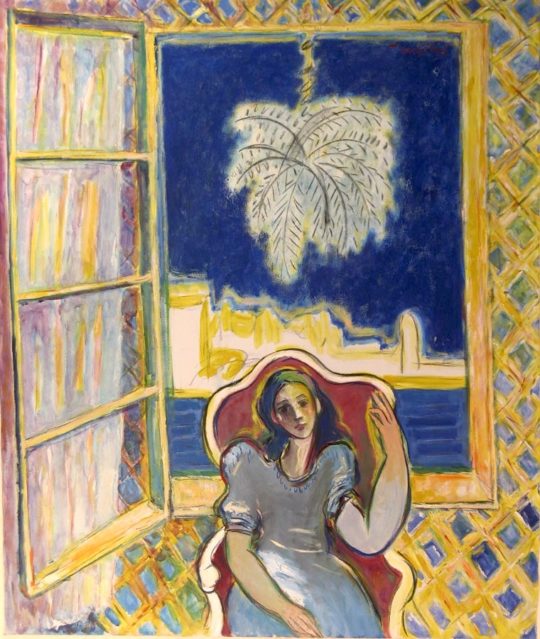

Figure No.29, 1989

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

Figure No.3, 1993

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

Figure No.31, 1989

30 x 36 inches (76.2 x 91.44 cm) -

Figure No.4, 1990

23 x 25 inches (58.42 x 63.5 cm) -

Figure No.7, 1990

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

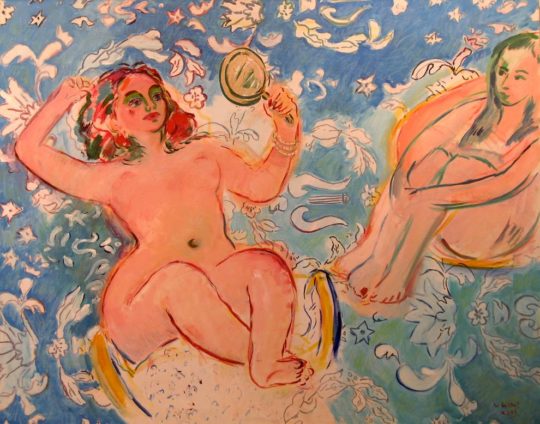

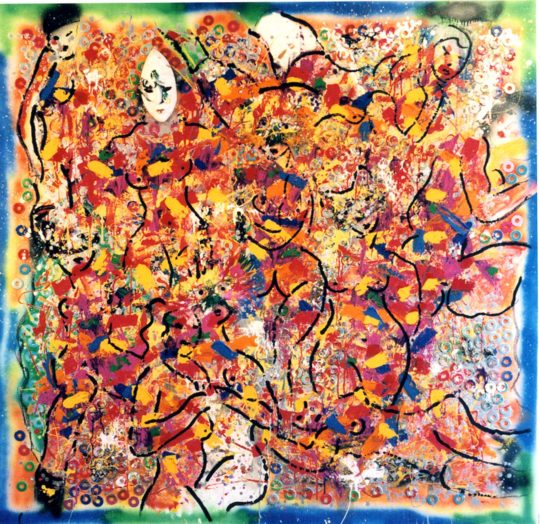

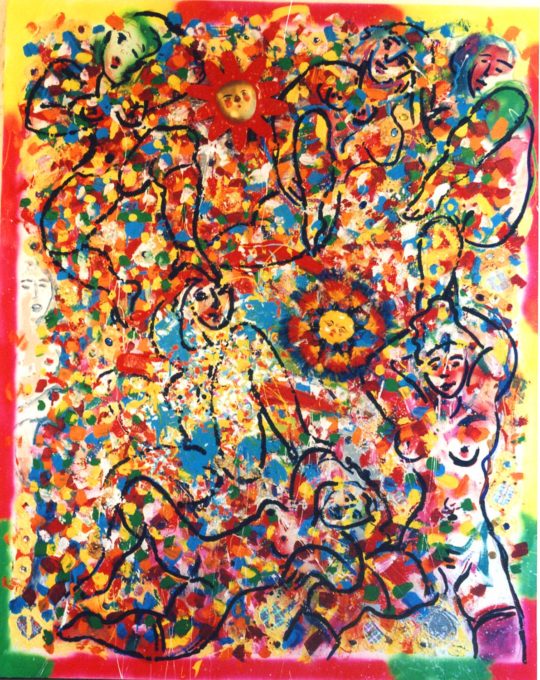

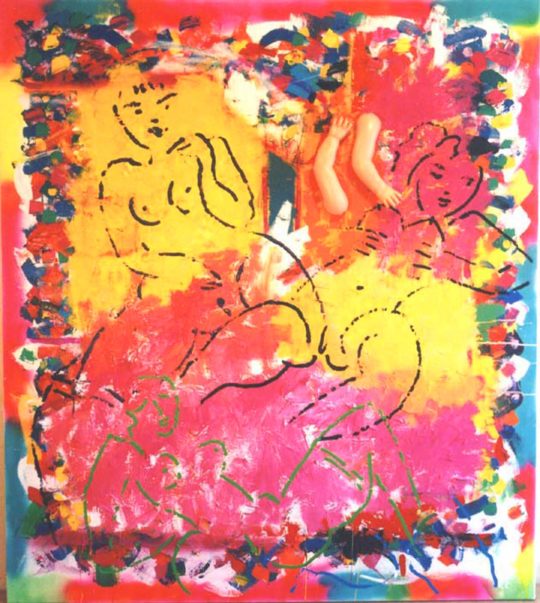

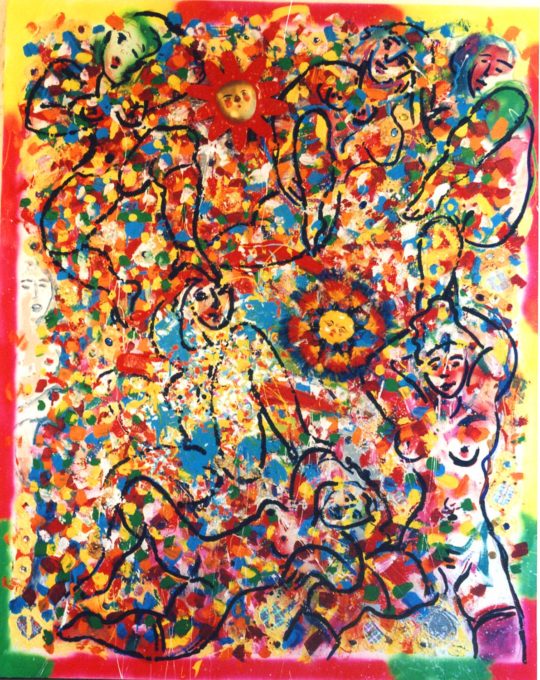

Goddess Series: Abundance, 2006

68 x 66 inches (172.72 x 167.64 cm) -

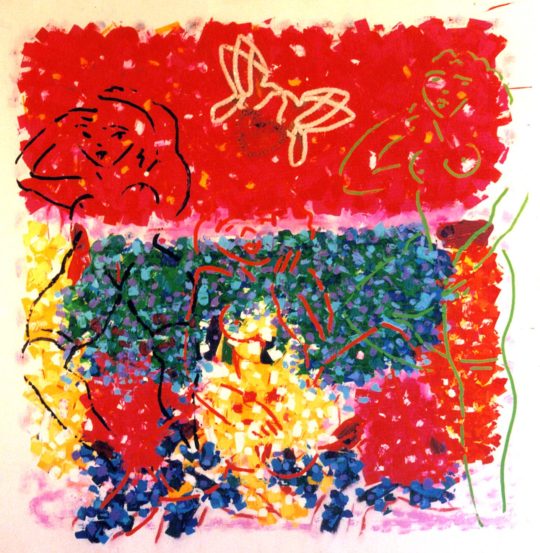

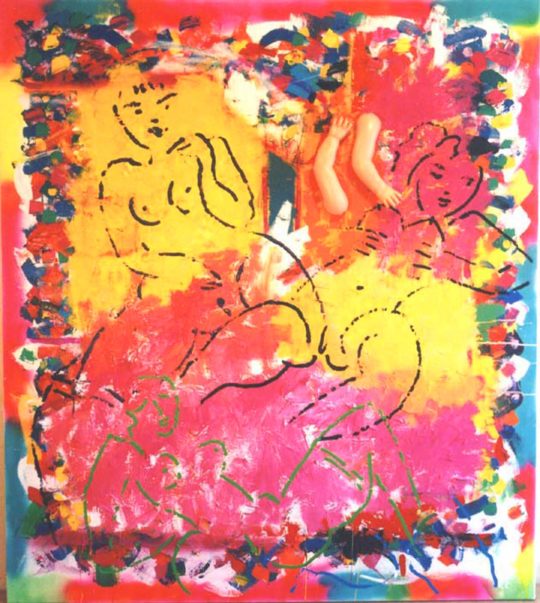

Goddess Series: Desire, 2006

68 x 66 inches (172.72 x 167.64 cm) -

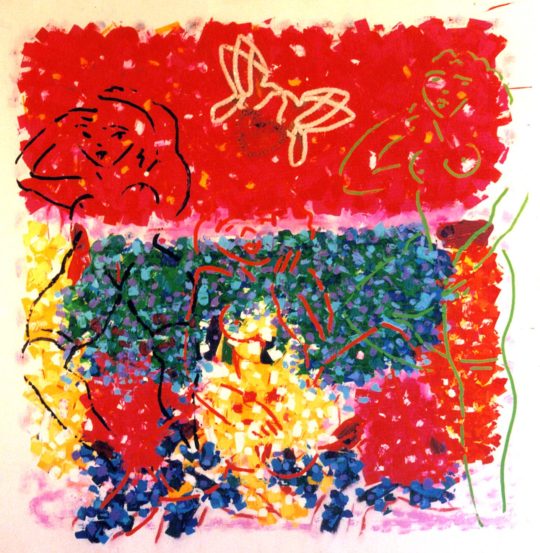

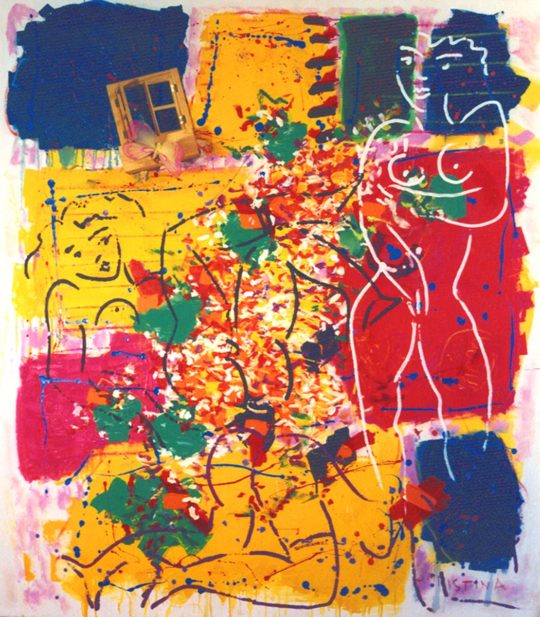

Goddess Series: Fire, 2006

60 x 68 inches (152.4 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: God, 1998

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

Goddess Series: Jewel, 2006

58 x 72 inches (147.32 x 182.88 cm) -

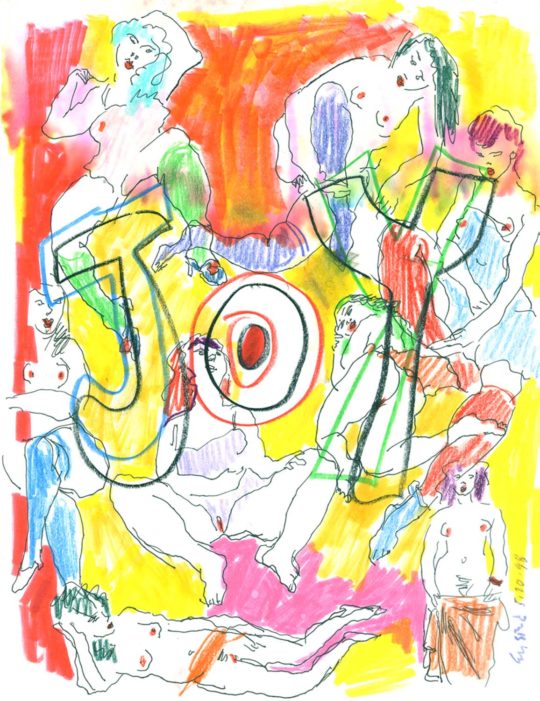

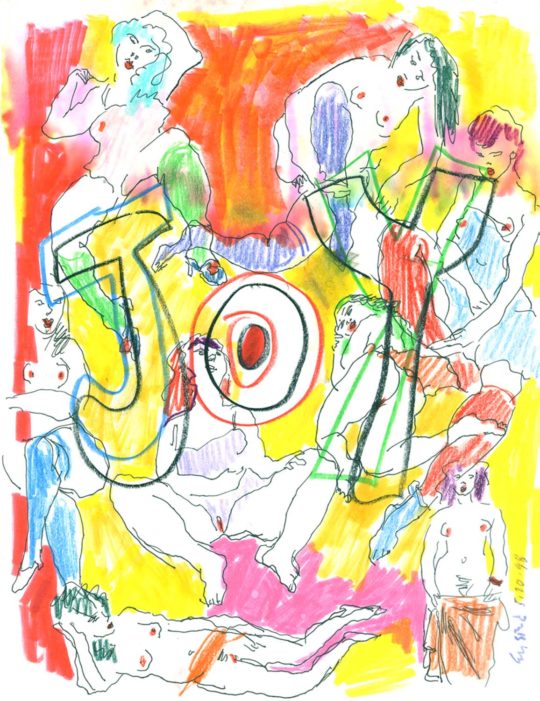

Goddess Series: Joy, 1998

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

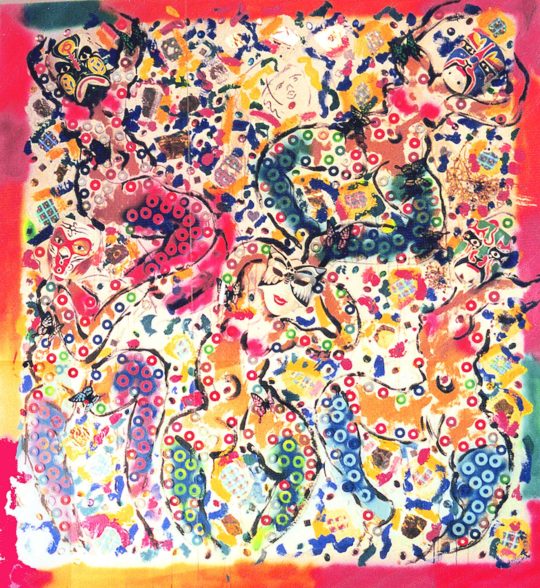

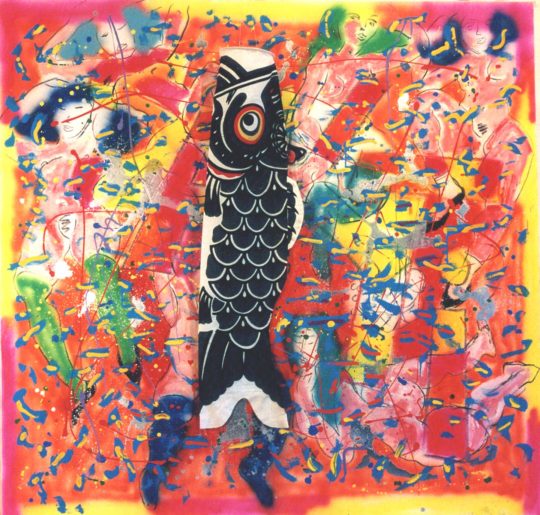

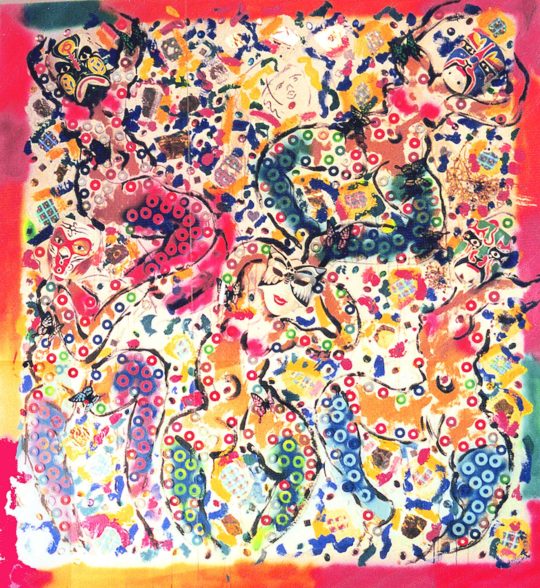

Goddess Series: Masks, 2006

66 x 72 inches (167.64 x 182.88 cm) -

Goddess Series: Mystery, 2006

66 x 68 inches (167.64 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: Source, 2006

60 x 68 inches (152.4 x 172.72 cm) -

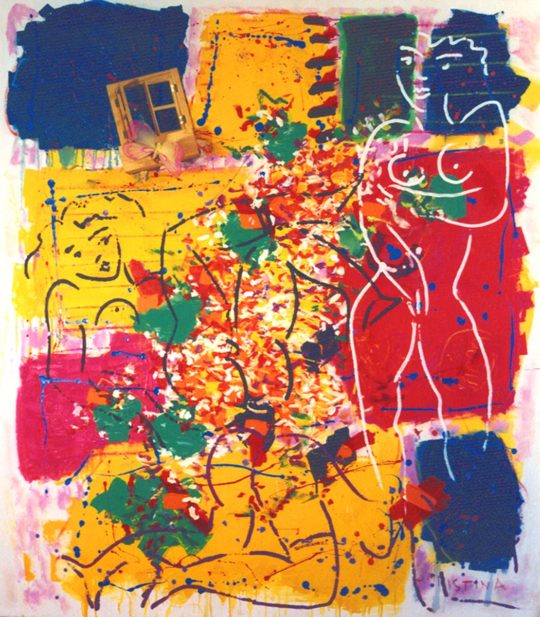

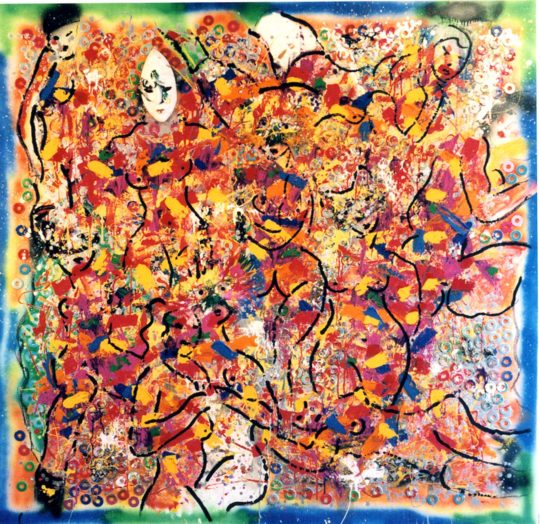

Goddess Series: Unity, 2006

80 x 68 inches (203.2 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: Vitality, 2006

60 x 68 inches (152.4 x 172.72 cm) -

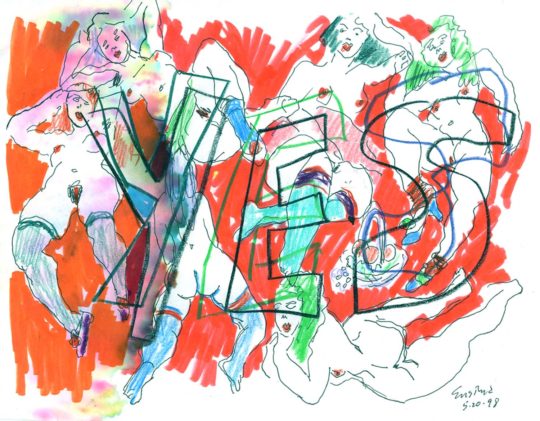

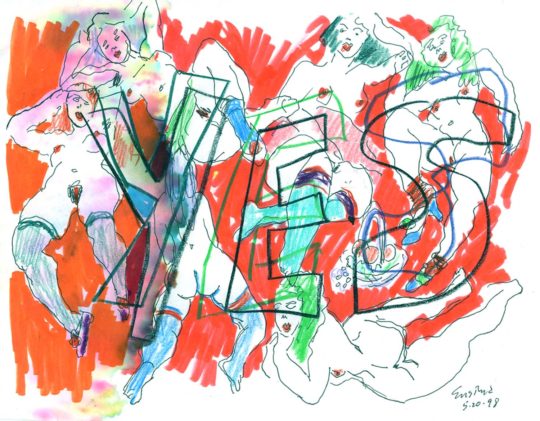

Goddess Series: Yes, 1998

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

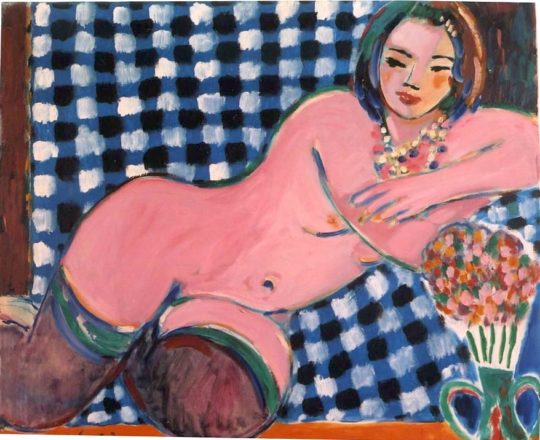

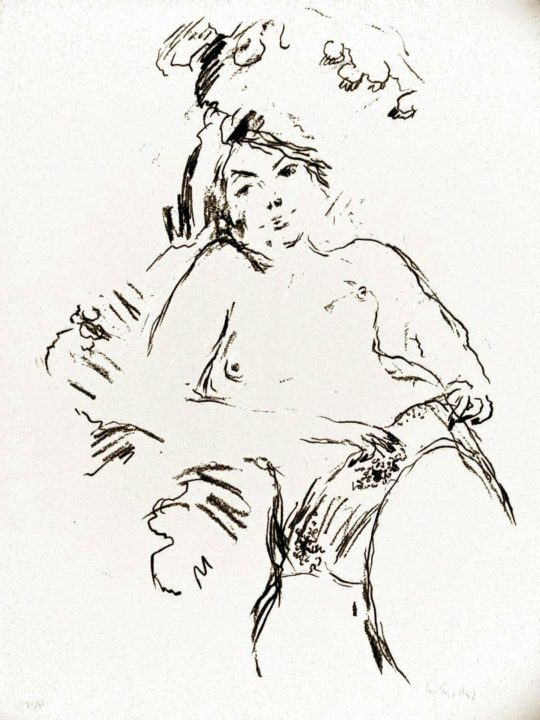

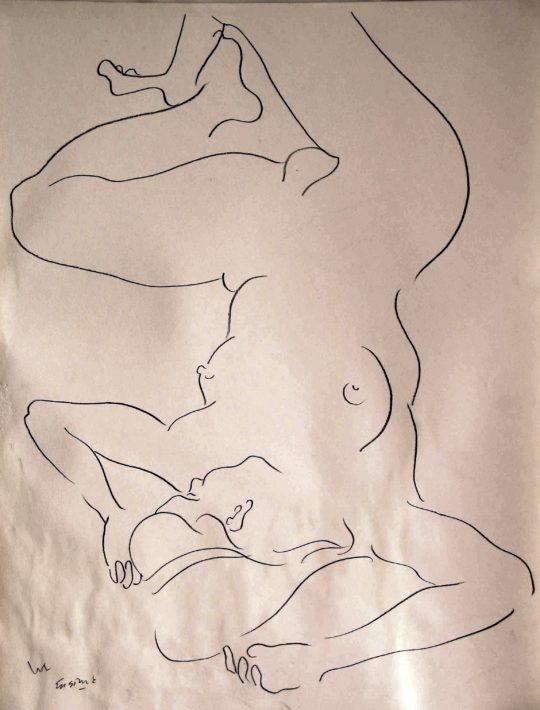

Nude study, 1980

20 x 26 inches (50.8 x 66.04 cm) -

Nude study No.131, 1990

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

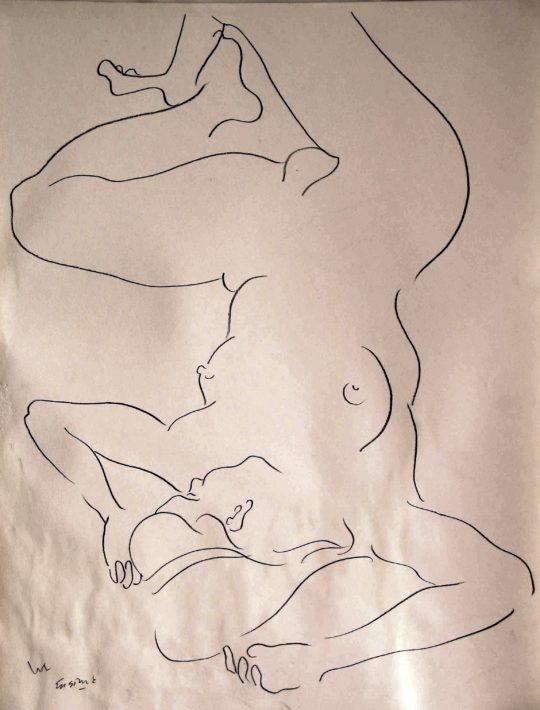

Nude study No.23, 1970

19 x 24 inches (48.26 x 60.96 cm) -

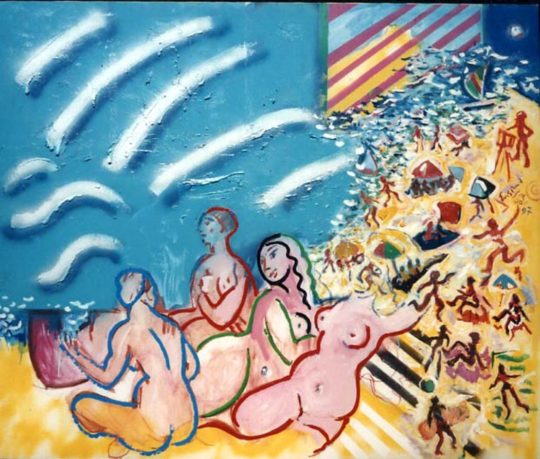

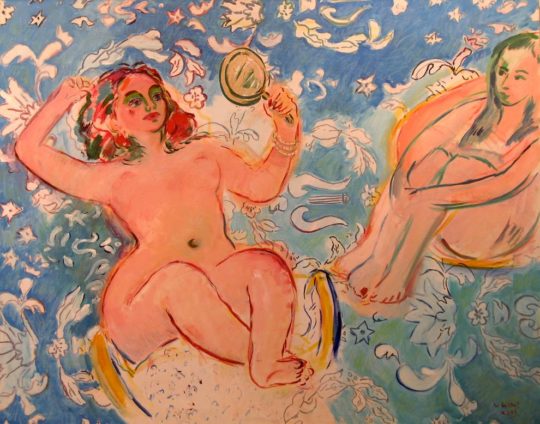

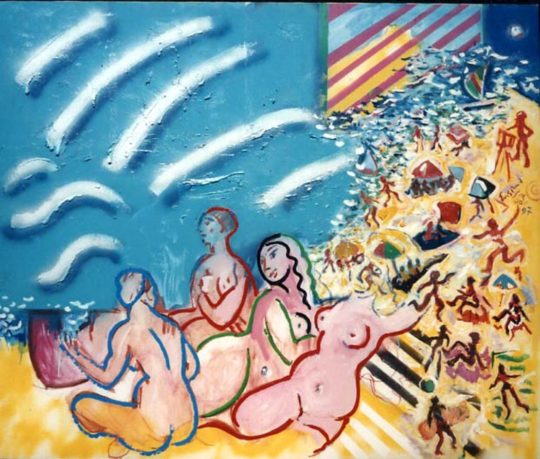

Nudes on the Beach, 1994

60 x 51 inches (152.4 x 129.54 cm) -

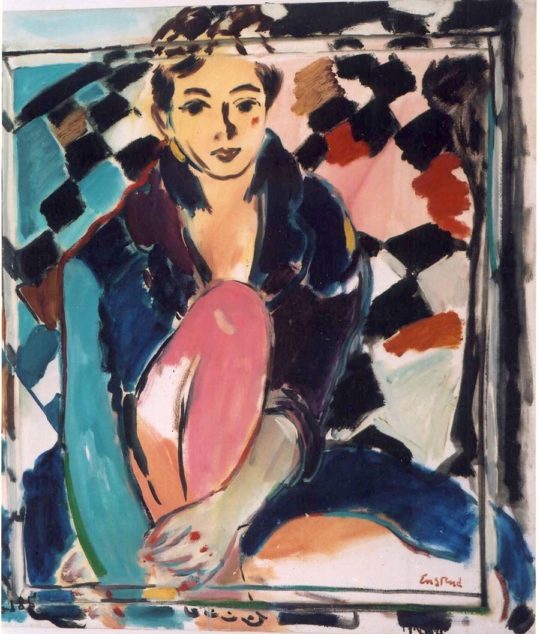

Timberlake Wertenbaker, 1968

26 x 32 inches (66.04 x 81.28 cm)

-

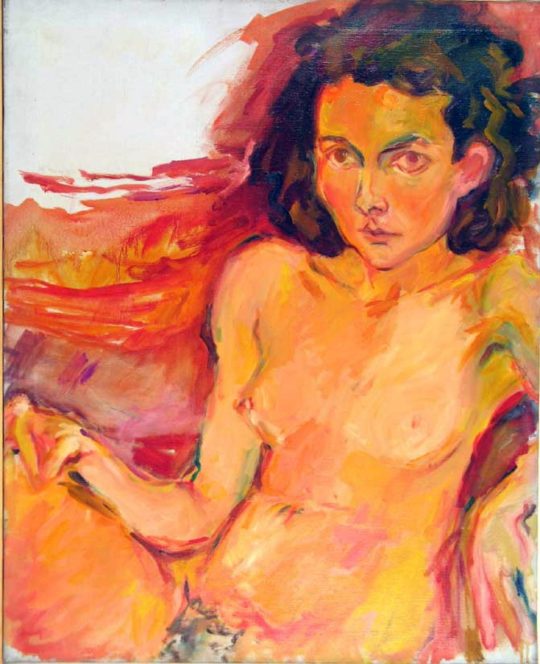

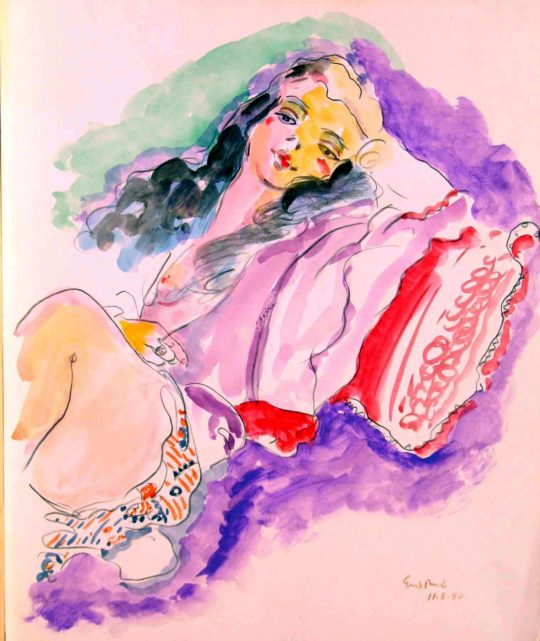

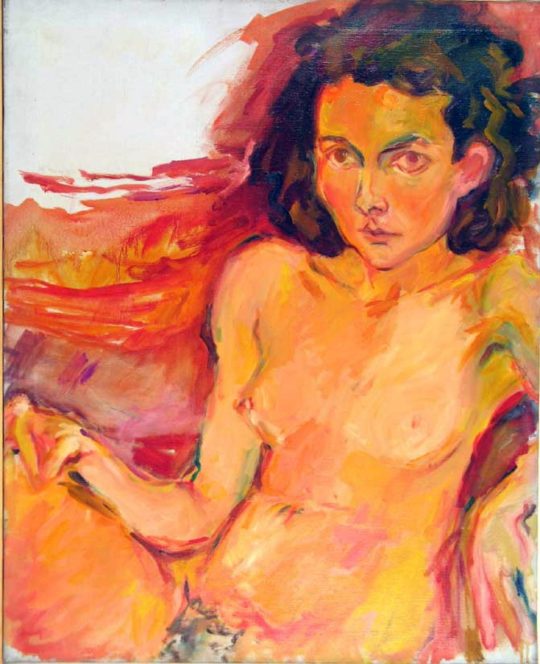

A Young Woman, 1985

22 x 28 inches (55.88 x 71.12 cm) -

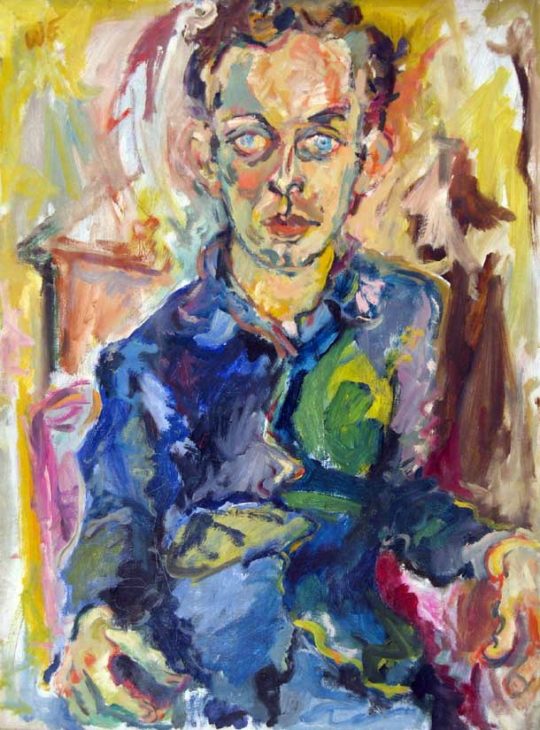

Bill Leach, Actor, 1966

24 x 32 inches (60.96 x 81.28 cm) -

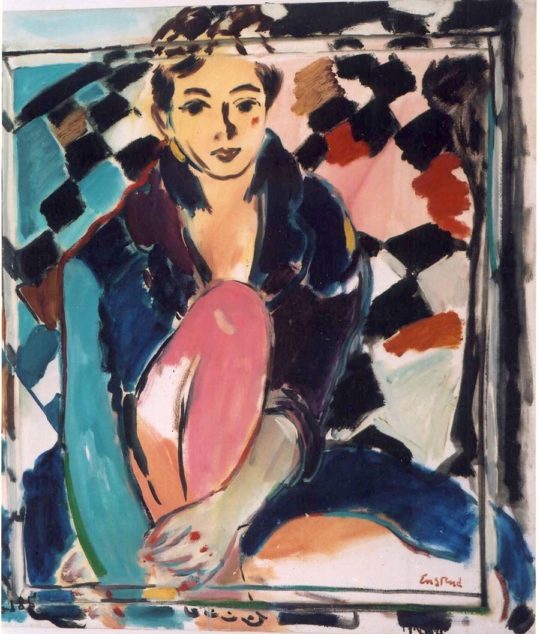

Crouching Nude, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Erotica No.19, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Erotica No.4, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Erotica No.41, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Erotica No.45, 1970

12 x 18 inches (30.48 x 45.72 cm) -

Figure No.1, 1993

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

Figure No.11, 1995

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

Figure No.12, 1990

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

Figure No.14, 1985

30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 60.96 cm) -

Figure No.26, 1985

36 x 46 inches (91.44 x 116.84 cm) -

Figure No.28, 1985

36 x 42 inches (91.44 x 106.68 cm) -

Figure No.29, 1989

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

Figure No.3, 1993

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

Figure No.31, 1989

30 x 36 inches (76.2 x 91.44 cm) -

Figure No.4, 1990

23 x 25 inches (58.42 x 63.5 cm) -

Figure No.7, 1990

27 x 23 inches (68.58 x 58.42 cm) -

Goddess Series: Abundance, 2006

68 x 66 inches (172.72 x 167.64 cm) -

Goddess Series: Desire, 2006

68 x 66 inches (172.72 x 167.64 cm) -

Goddess Series: Fire, 2006

60 x 68 inches (152.4 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: God, 1998

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

Goddess Series: Jewel, 2006

58 x 72 inches (147.32 x 182.88 cm) -

Goddess Series: Joy, 1998

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

Goddess Series: Masks, 2006

66 x 72 inches (167.64 x 182.88 cm) -

Goddess Series: Mystery, 2006

66 x 68 inches (167.64 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: Source, 2006

60 x 68 inches (152.4 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: Unity, 2006

80 x 68 inches (203.2 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: Vitality, 2006

60 x 68 inches (152.4 x 172.72 cm) -

Goddess Series: Yes, 1998

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

Nude study, 1980

20 x 26 inches (50.8 x 66.04 cm) -

Nude study No.131, 1990

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

Nude study No.23, 1970

19 x 24 inches (48.26 x 60.96 cm) -

Nudes on the Beach, 1994

60 x 51 inches (152.4 x 129.54 cm) -

Timberlake Wertenbaker, 1968

26 x 32 inches (66.04 x 81.28 cm)

Art has a mission to perform. It should be a means of communication, with the same purpose as language. I do not believe in “art for art’s sake” – a pretty package but empty inside! That is idle chatter. Instead, a painting should be a means of establishing contact with others.

The artist has a responsibility to envision and embrace the whole world in a spirit of love — to see and rejoice in the grand unity of creation. Therefore, the artist paints for the spiritually starving; for an audience of the blind. A good painter should be able to paint anything — but a great painter is the servant of compulsions which are ordained by the very structure of the soul. He or she is not interested in policies but in values — this is our field of battle.

I believe in the miracle of the great blinding moment of illumination when the human spirit — radiating light and laughter, joy and love — nourishes the intuition. When your spirit trembles with joy then art has found its true form and place, and the artist can play like a fountain without strife, without even trying.

Art cannot be bound to a theology, theory, or system. It preaches nothing. It is a purifying factor. Its essence is joy and love, which unravels the tensions and relaxes the soul. The secret of art’s healing power is in the viewer and not the artist. The only measure is reaction!

In a world of change, one constant is the human gift of extending the boundaries of the human spirit ever-wider. And, therein lay the vocation of the creative artist: to capture his insights into that human spirit and manifest them in his art.

Current trends find some artists trying to saturate the world with their own anguish. This is thin fare for hungry viewers. Somewhere at the heart of things, artists are still lazy of spirit. They have not become desperate enough or determined enough. By a force of will, the lock on the door must be broken and the door must be knocked down in order to become the poet, the artist — the one who dares!

Man may travel around the world and colonize to the end of the earth – and yet never hear the singing of the universe.

Through expressing compassion and joy, art creates a possibility for others to experience joy and happiness — and this is a real service to mankind.

— Wayne Ensrud

The eroticism of the female nude has been a recurrent theme throughout the works of Wayne Ensrud. Ever since he attended a lecture in 1952 by Oskar Kokoschka, the great Austrian Expressionist, Ensrud has been dedicated to the act of seeing and painting as a powerful emotional experience. Kokoschka inspired Ensrud to dig deeper than other young contemporary artists, most of whom had been misled into thinking that a focus of massive energy and emotion were enough to become a great painter. Instead, Ensrud came to understand that painting was a metaphysical act, charged by the spirit. A review of Ensrud’s erotica leaves no wonder why Kokoschka considered him to be his only protégé.

For Ensrud, insight is far more important than the subject itself. He notices that when most people view a beautiful nude female model, their eyes are wide open but he regrets that they remain unconscious of her aura, her spirit. Sex is often the dominant thought. “Sex is about brief and often incredible transcendental moments,” says Ensrud. “But when I’m painting the model I feel and see vibrations, pulsations. It’s like music. I could gaze for hours. She is mysterious. She is pure seduction, yet there’s a certain purity of the relationship. I’m not thinking about her breasts, hips, and legs. I’m sensing her rhythm. I’m picking up her libido, and she knows it. And because she senses my absorption into her metaphysical space, she provides an openness — a gentle receptivity — to this higher range of vibrations.”

Although the stereotype of the artist having sex with his models may be true (Ensrud cites more than 135 women with whom he has had sex versus 122 for Casanova), when it comes to capturing them on canvas he enters another world. “I try to capture an experience of timelessness. The movement of my brush or pen is always flowing, never settling. It’s as if I am floating in a dream world where there is a suspension of time. And I never talk, often for hours, until I am finished. It is definitely a meditative state, an indescribable pushing toward the eternal. My feet aren’t on the earth, that’s for sure. I can only enter that zone when I am in the artistic act of capturing her essence; otherwise, the experience just can’t be conveyed.”

The subject may be erotica but Ensrud becomes so completely immersed that he prefers to refer to his paintings and drawings as “witnesses of various states of mind where I release and surrender myself to the spirit of the subject. I’m not a Buddhist or a Zen master but I can hold that transcendent state longer now than when I was younger. Maybe these are brief lightning flashes of how Buddha actually lived. I just know that the experience is a totally personal adventure that can only be taken alone.”

In the decades that Ensrud came to know Oskar Kokoschka, he says his master never talked about painting. “He had no answers,” says Ensrud, “only a directive: ‘Climb the mountain.’ He knew the truly great teachers don’t teach at all. They just exude. They ignite a fire in our consciousness. Kokoschka did speak eloquently about psychic energy, and I was a quick study. But in the end there is no one who can explain the experience of aesthetic ecstasy. After all, that’s why there’s art. The answer really lies in the reaction of the viewer. The viewer must respond with feeling.”

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2012 Able Fine Art, New York NY

2012 New Art Center, New York NY

2011 High Line Open Studios, New York NY

2010 Great Neck Arts Center, NY

2008 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Great Neck Arts Center, NY

2007 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Gardens Gallery Center, Palm Beach Gardens, FL

Duboeuf Cultural Museum, Romaneche-Thorins, France

2006 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

2005 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

2004 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

2003 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Galerie des Artistes, Puerta Vallarta, Mexico

Ravsen Fine Art, New Canaan CT

2002 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

2001 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Robert Mondavi Gallery, Napa Valley CA

Galleria Luna, Half Moon Bay CA

Louis Aronow Gallery, San Francisco CA

2000 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Galleria Luna, Half Moon Bay CA

Christopher Hill Gallery, St. Helena CA

Ravsen Fine Art, New Canaan CT

1999 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

The Federation of Chateauneuf-du-Pape, France

1998 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

1997 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Musee du Vin, Chateau Cos D’Estournel, Bordeaux, France

1996 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

1995 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

1994 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

1993 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Horseneck Gallery, Greenwich CT

Gallery and Company, Tokyo, Japan

Artistic Galleries, Scottsdale AZ

Washington Avenue Gallery, Minneapolis MN

Silene Gallery, Boston MA

1992 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Wally Gallery, Los Angeles CA

Money and Economy, Ft. Lauderdale FL

1991 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Gallery and Company, Tokyo, Japan

Klabal Gallery, Minneapolis MN

1990 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Galerie Damien, Paris, France

1989 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Carmichael-Peterson Gallery, Minneapolis MN

Artbanque Gallery, Minneapolis MN

1988 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Gallery ANA, Tokyo, Japan

Hallonen Gallery, Minneapolis MN

Klabal Gallery, Minneapolis MN

1987 Sherry-Lehmann, New York, NY

Ruffner Gallery, Grosse Pointe Farms MI

Relais du Margaux, Bordeaux, France

1986 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Peach Tree Center, Atlanta GA

1985 Sherry-Lehmann, New York NY

Parker Gallery, Newport RI

1984 Virginia Lynch Gallery, Rhode Island

Sansiao Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

1983 Symon Gallery, Kansas City, Missouri

Gallery on the Square, Kansas City Missouri

1982 University of Connecticut

Buffalo Museum of Science NY

1981 Apogee Gallery, Boston MA

New England Center for Contemporary Art

1979 Bristol Museum of Art

Loring Gallery, Cedarhurst NY

1978 Simon’s Rock Early College

1977 South Hill Library, VA

1976 Maas Bros. Gallery, Tampa FL

The Gallery of Art, Panama City FL

1975 French Institute-Alliance Francaise, New York NY

1974 National Arts Club, New York NY

1973 Automation House, New York NY

1970 Modern Masters Gallery, New York NY

1961 Fine Gallery, San Francisco CA

Selected Group Exhibitions

2011 Benrimon Contemporary, New York NY

Designlawn Showcase, New York NY

2010 Thomas Jaeckel Gallery, New York NY

2009 Great Neck Arts Center, NY

1993 Beard Gallery, Minneapolis MN

1990 St. John’s University, St. Cloud MN

1985 T.R. Gallery, New York NY

1983 Arras, East Trump New York NY

Sansiao Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

1982 Old State House Museum, Hartford CT

Slater Museum, Norwich CT

Buffalo Museum of Science, NY

University of Connecticut

Summers Gallery, New Orleans LA

Pioneer Square Gallery, Seattle WA

Owl Gallery, San Francisco CA

Weinger Gallery, New York NY

1981 Stuart Gallery, New York NY

Circle Gallery, Chicago IL

Meyers Gallery, Chevy Chase MD

1980 Village Gallery, New York NY

University of Florida

1979 Gallery 306, Philadelphia PA

1977 Eric Schindler Gallery, Richmond VA

1976 Haller Gallery, New York NY

1975 Five Uptown Independent Artists, New York NY

Haller Gallery, New York NY

1974 Five Uptown Independent Artists, New York NY

Picturline Gallery, Roslyn NY

1973 Five Uptown Independent Artists, New York NY

1972 National Arts Club, New York NY

1960 Oakland Art Museum, CA

1956 Minneapolis Institute of Art

Awards

Oscar d’Italia

Lever House Award

Minnesota Hall of Fame

Rothschild Design Award

Commandeur d'Honneur du Bontemps de Medoc et des Graves

Compagnon de Beaujolais

Grappileur de Beaujolais

Book References

Who’s Who In American Art

Who’s Who in the East

Men of Achievement

American Artists: An Illustrated Survey of Leading Contemporary Americans