The Feral Abstract Expressionist of Honey Island Swamp

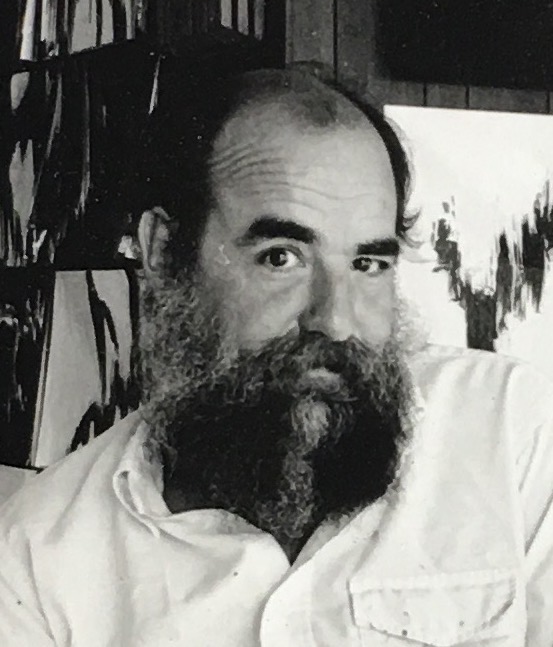

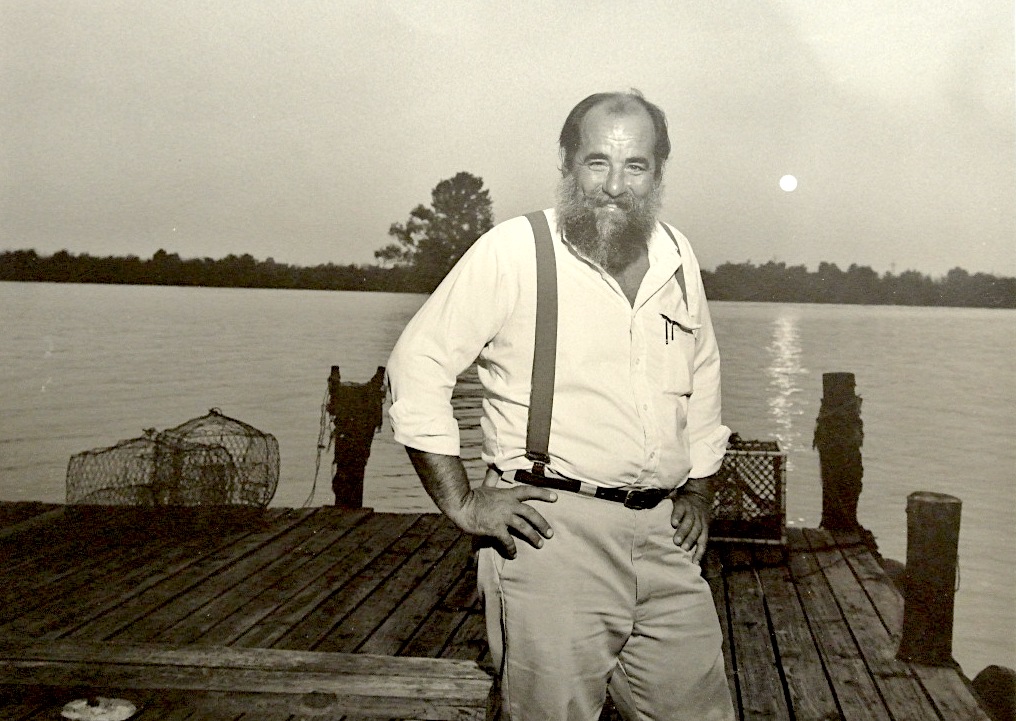

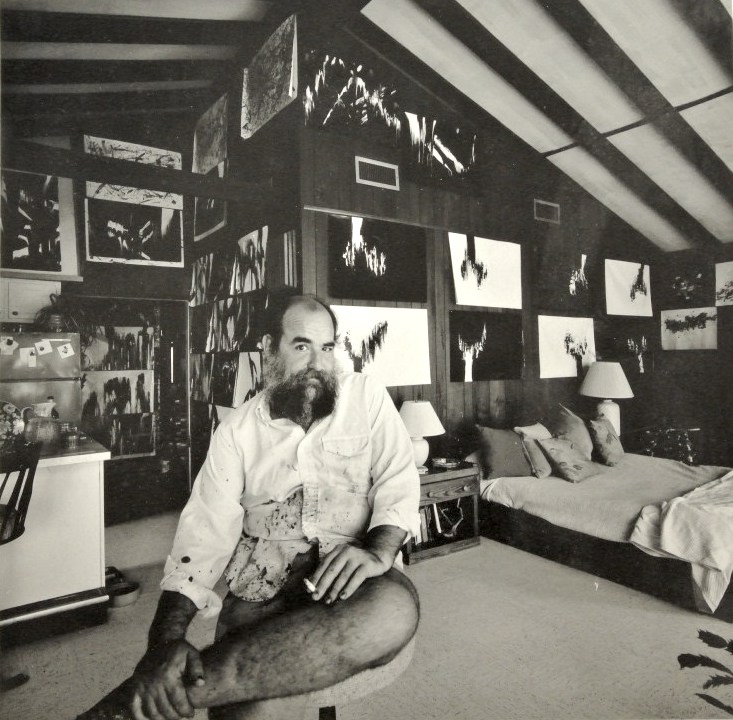

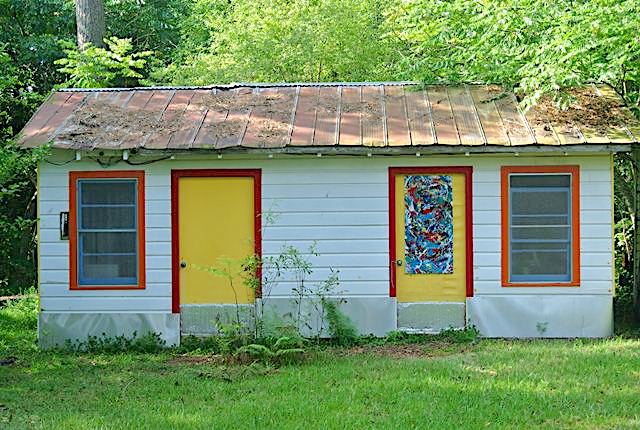

For 45 years Tom McNease lived in the bayous of Saint Tammany Parish, the most southeastern region of Louisiana. Nearly 300 square miles of this region is water, with creeks weaving through swamps of bald cypress, their branches draped with flowing silver-gray Spanish moss. The majority of the population is composed of otters, muskrats, bears, turtles — and the largest number of alligators in the state. Natives call it the North Shore, with Lake Pontchartrain being its southernmost border. McNease moved several times within this region, building a cottage at each location at the edge or in the middle of the bayou. For the last fifteen years of his life he lived alone at the edge of Honey Island Swamp, a 250-square-mile protected wildlife sanctuary forming Louisiana’s easternmost border with Mississippi. A recluse, he loved the swamp and could easily launch his kayak in the Old Pearl River, which ran its course 40 miles down to the Gulf of Mexico. Fully immersed in this environment, this completely self-taught Outsider artist developed a large body of artworks and a unique technique not revealed until his passing in 2014.

For 45 years Tom McNease lived in the bayous of Saint Tammany Parish, the most southeastern region of Louisiana. Nearly 300 square miles of this region is water, with creeks weaving through swamps of bald cypress, their branches draped with flowing silver-gray Spanish moss. The majority of the population is composed of otters, muskrats, bears, turtles — and the largest number of alligators in the state. Natives call it the North Shore, with Lake Pontchartrain being its southernmost border. McNease moved several times within this region, building a cottage at each location at the edge or in the middle of the bayou. For the last fifteen years of his life he lived alone at the edge of Honey Island Swamp, a 250-square-mile protected wildlife sanctuary forming Louisiana’s easternmost border with Mississippi. A recluse, he loved the swamp and could easily launch his kayak in the Old Pearl River, which ran its course 40 miles down to the Gulf of Mexico. Fully immersed in this environment, this completely self-taught Outsider artist developed a large body of artworks and a unique technique not revealed until his passing in 2014.

McNease was born on November 8, 1947, in Meridian, Mississippi, a railway hub for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and the Southern Railway. His father, Luke, was a railroad engineer. His mother, Mary Francis McNease, a homemaker. The son’s original aspiration was to become a doctor, and in 1965 he enrolled in the pre-med program at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Precocious but always restless, he was dismissed for reasons never fully clarified. He then attended Southeastern University in Hammond, Louisiana, as a zoology major and soon married. After graduating in 1969 he taught science at a rural public school. Most of his students lived in poverty but he soon quit, saying he was unable to bear the pain of dealing with many children who had been abused. A series of jobs followed, including plumber’s helper, newspaper writer, and car salesman.

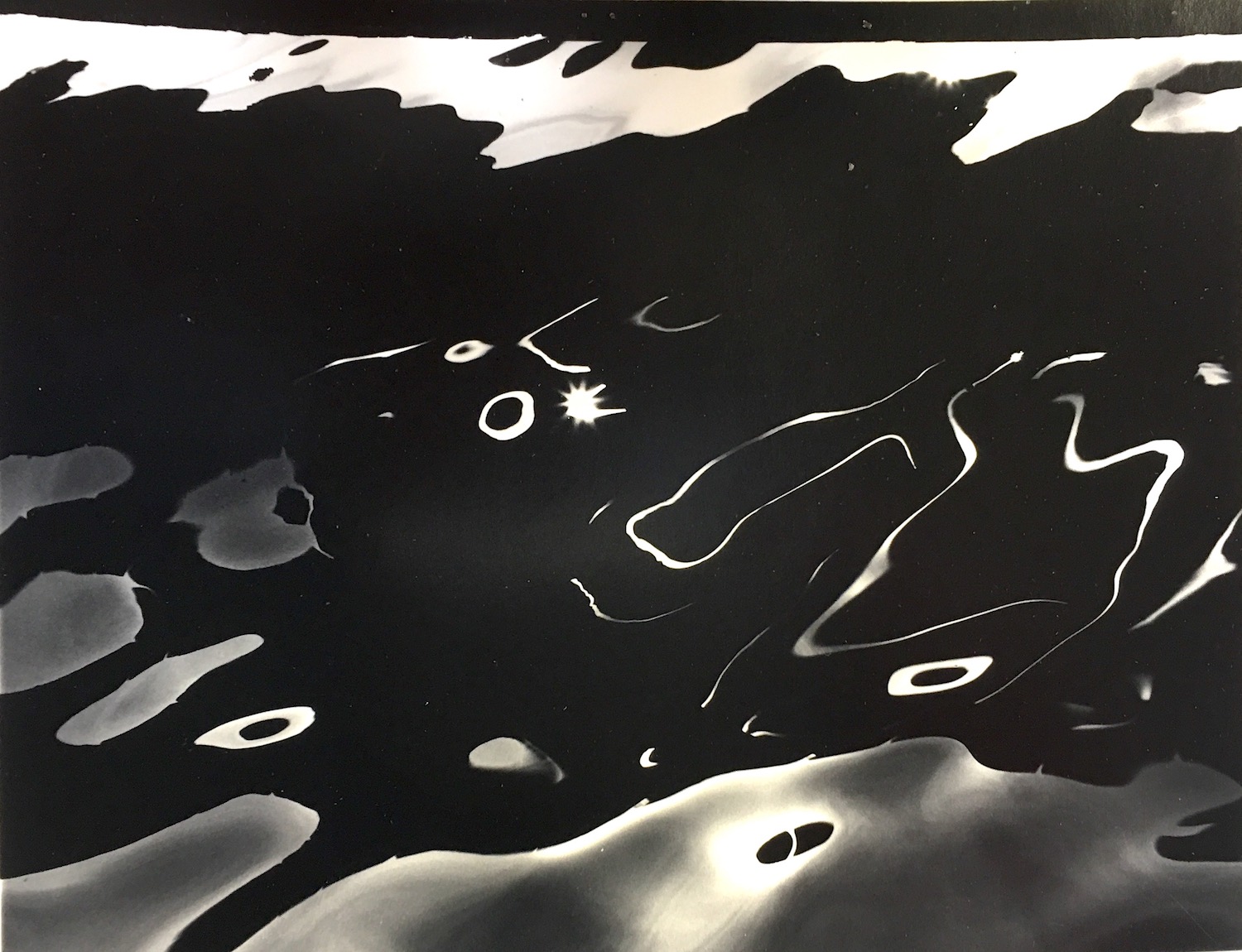

In 1970, while living in Mandeville on North Shore of Lake Pontchartrain, McNease became absorbed in photography. He immediately focused upon natural abstraction in the vein of Minor White and Wynn Bullock as well as certain works by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Brett Weston. He was also aware of the great romantic and mystic photographer of New Orleans, Clarence John Laughlin. With his immersion in photography came the beginnings of what would become a large archive of writings on painting, photography, philosophy, psychology, and the environment.

To seek that point at which the thing becomes a void in the eyes of the viewer, allowing him his own thoughts…To use that term again, “catalyst,” and to use Weston’s term, “the thing itself”… But to go beyond that. To transcend the actual subject. To use that subject as a vehicle into one’s own unknown cosmos.

To seek that point at which the thing becomes a void in the eyes of the viewer, allowing him his own thoughts…To use that term again, “catalyst,” and to use Weston’s term, “the thing itself”… But to go beyond that. To transcend the actual subject. To use that subject as a vehicle into one’s own unknown cosmos.

— Tom McNease, November 11, 1975

McNease’s wrote that his photographic images consistently “transcend the actual subject.” By 1975, when the photography market was in its infancy, he had built up an impressive body of work and secured exhibitions at pioneering galleries in Dallas, Santa Fe, Oregon City, and New York City — and that year his photographs were published in the Swiss magazine, Camera. In 1977 he produced Illuminations, a limited edition portfolio of ten silver prints.

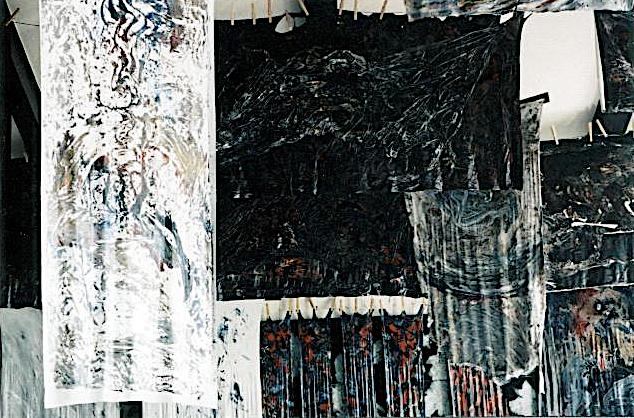

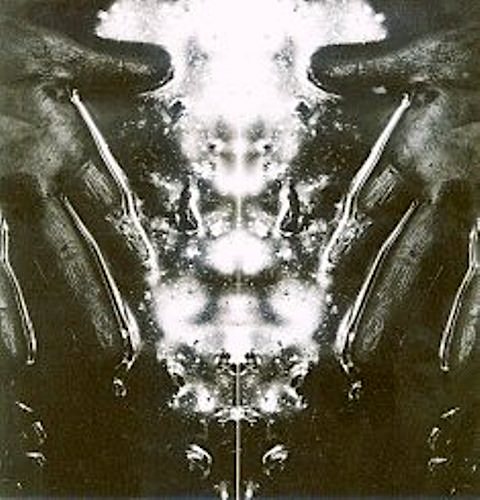

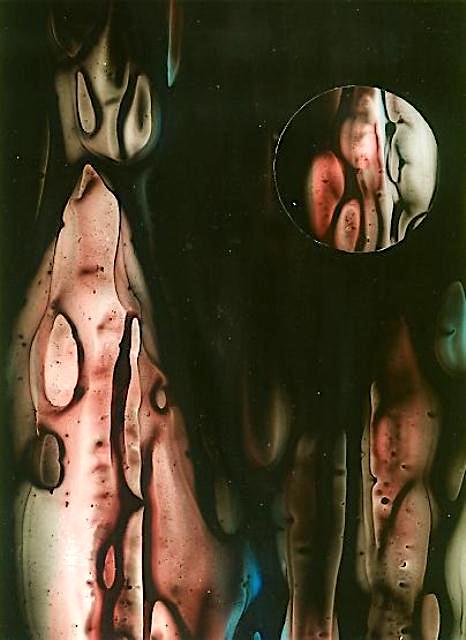

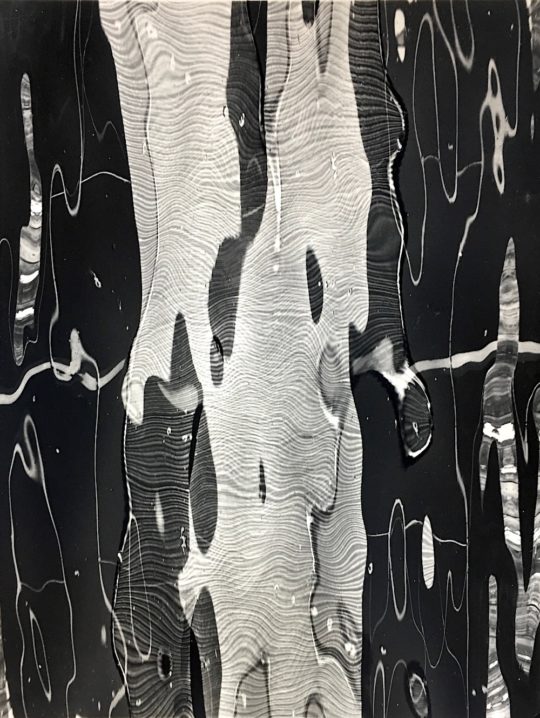

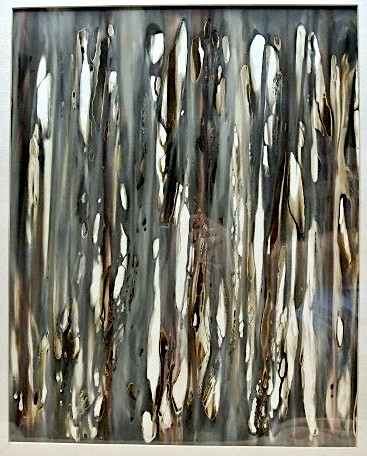

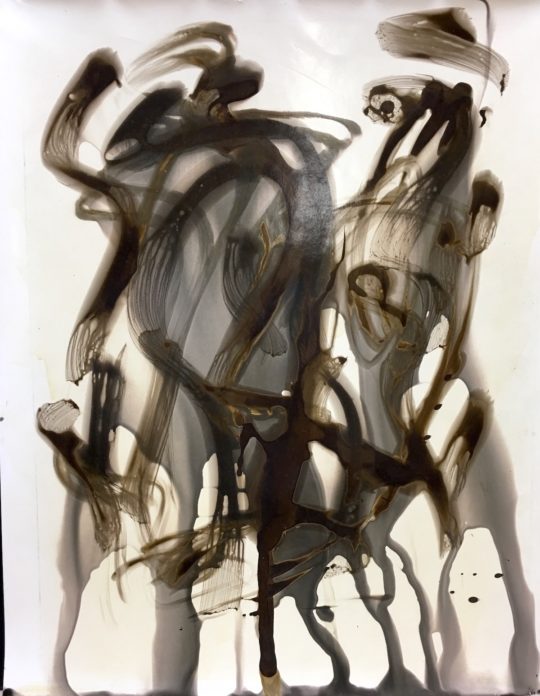

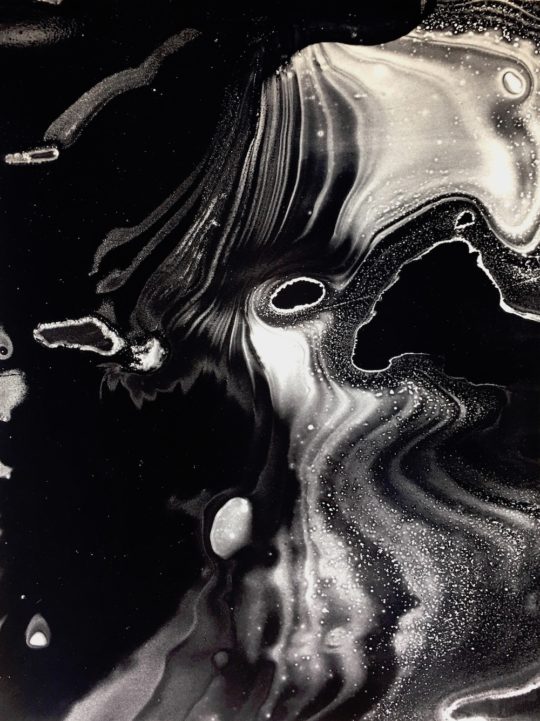

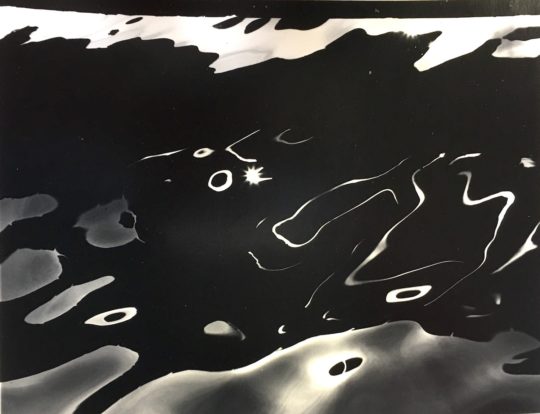

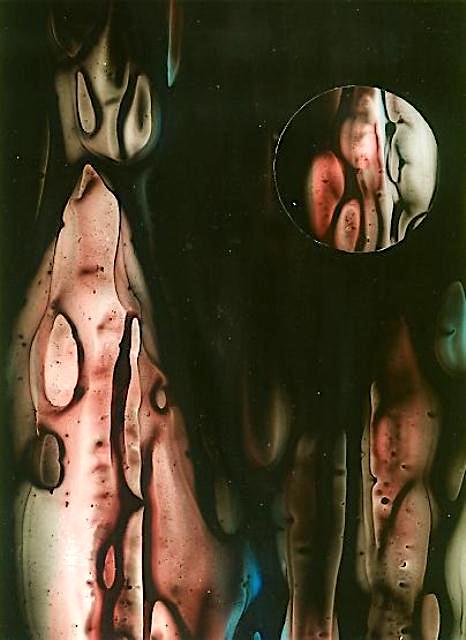

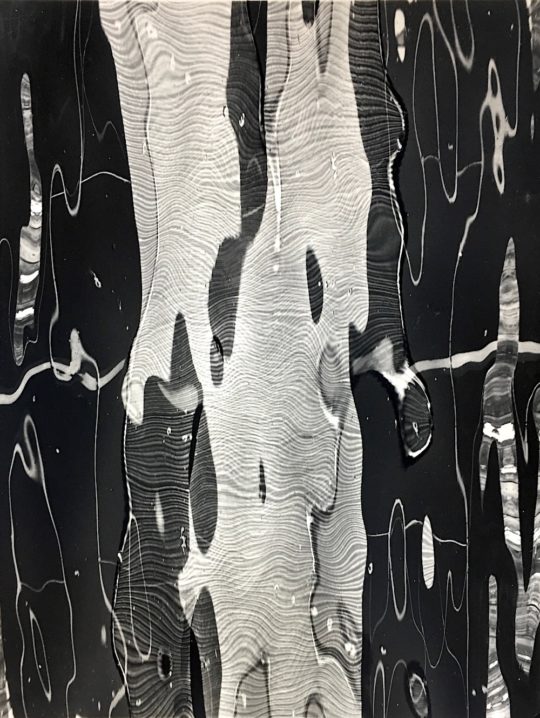

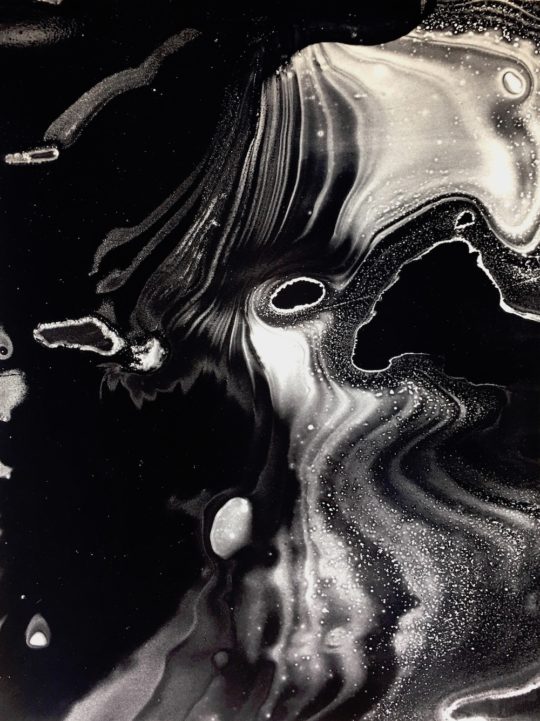

In 1979 McNease built a cottage of virgin cypress with no nails. It was under a huge old oak tree in the swamp. He installed a glass roof so that as he lay down he could gaze to the skies both day and night. That year, the New Orleans Museum of Art purchased three of his abstract expressionist works — chemigrams — unique images created by manipulating chemicals on the surface of photographic paper. He also altered other abstract images by painting on his 4 x 5 negatives. His photographs were acquired by the collections of the Exchange National Bank of Chicago, The Prestonwood Collection of Photographic Art (Dallas), and the Louisiana Arts and Science Centre (Baton Rouge).

Because his wife was striving to become a ballerina the couple made extended stays in New York where McNease enjoyed several exhibitions at The 4th Street Photo Gallery, the last of which occurred in 1981. Increasingly, his wife felt compelled to remain in New York but McNease instead felt the inexorable drawing power that the swamp held over his psyche. This impasse led to their divorce in 1983. Coincidentally, that year he was featured in the Macmillan Biographical Encyclopedia of Photographic Artists and Innovators.

Because his wife was striving to become a ballerina the couple made extended stays in New York where McNease enjoyed several exhibitions at The 4th Street Photo Gallery, the last of which occurred in 1981. Increasingly, his wife felt compelled to remain in New York but McNease instead felt the inexorable drawing power that the swamp held over his psyche. This impasse led to their divorce in 1983. Coincidentally, that year he was featured in the Macmillan Biographical Encyclopedia of Photographic Artists and Innovators.

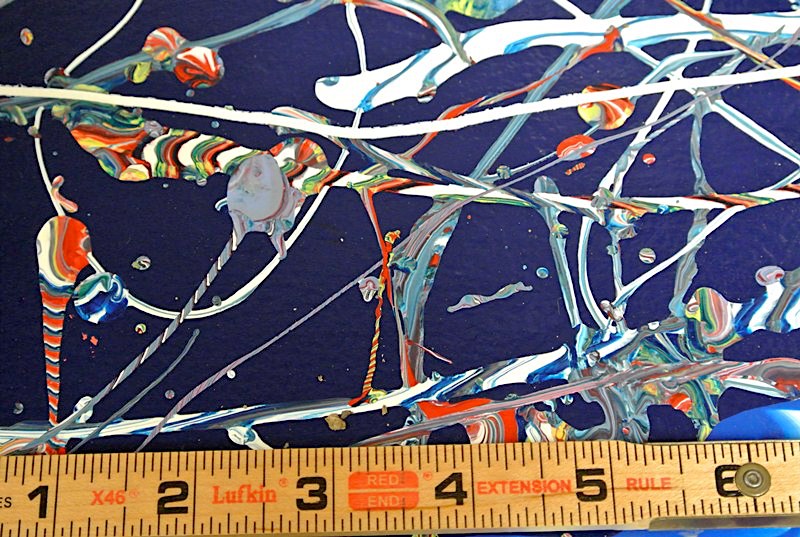

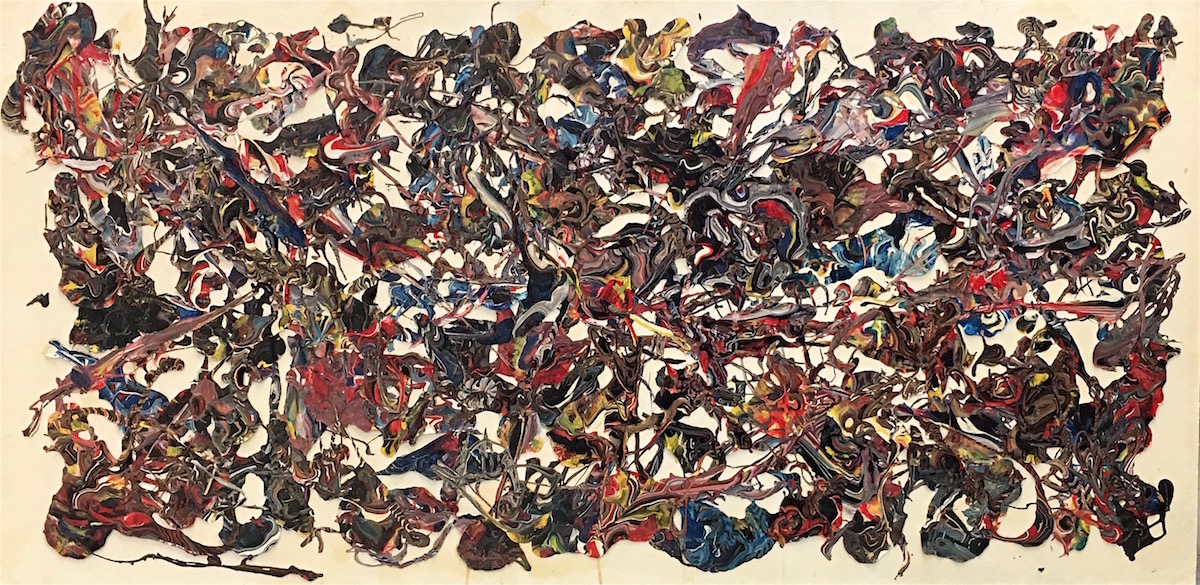

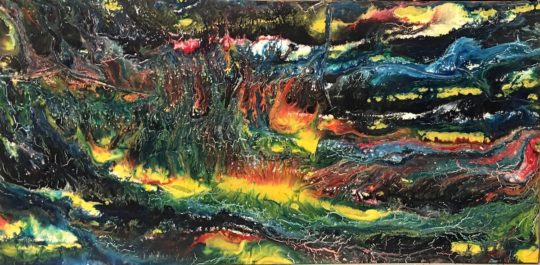

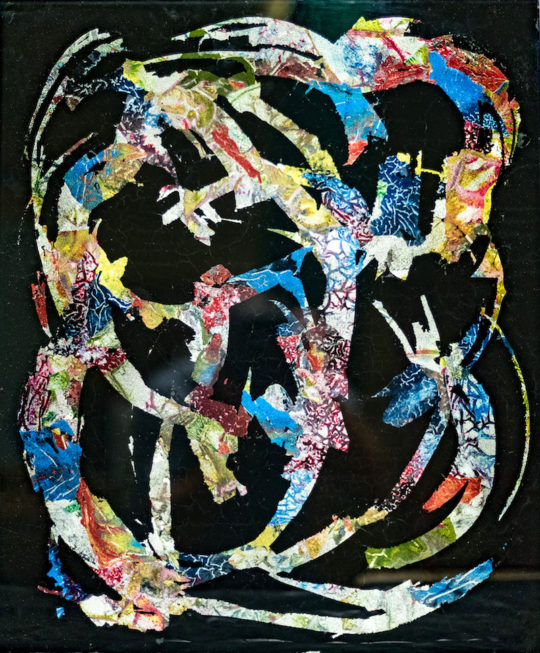

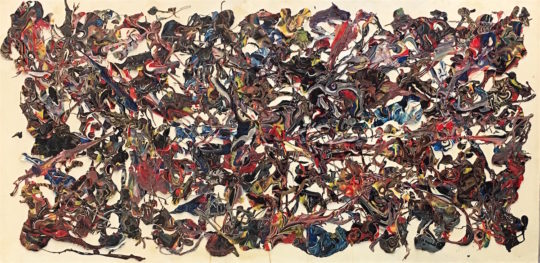

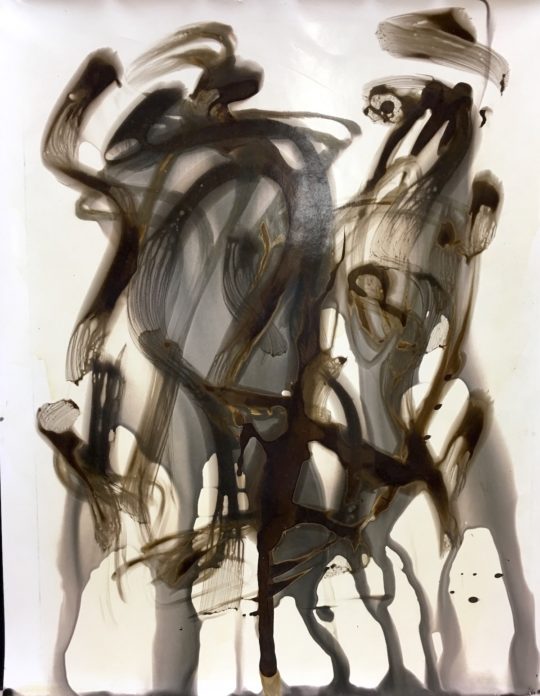

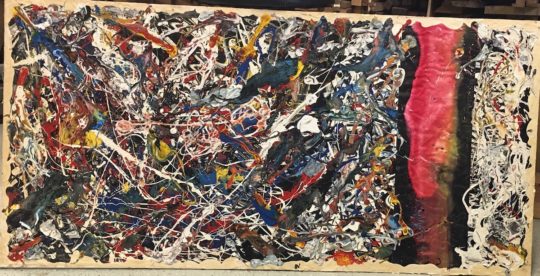

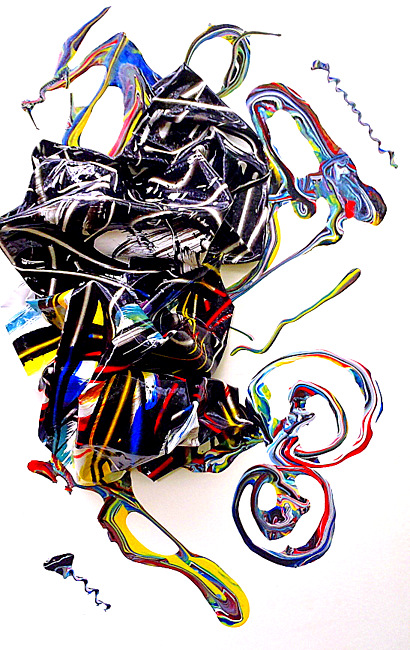

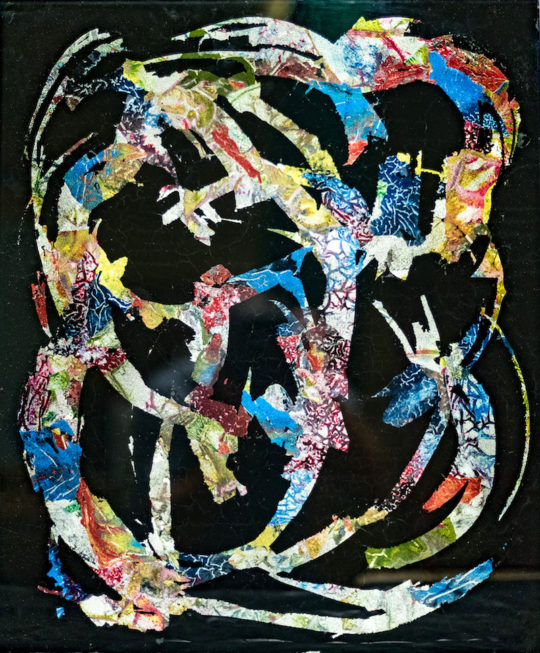

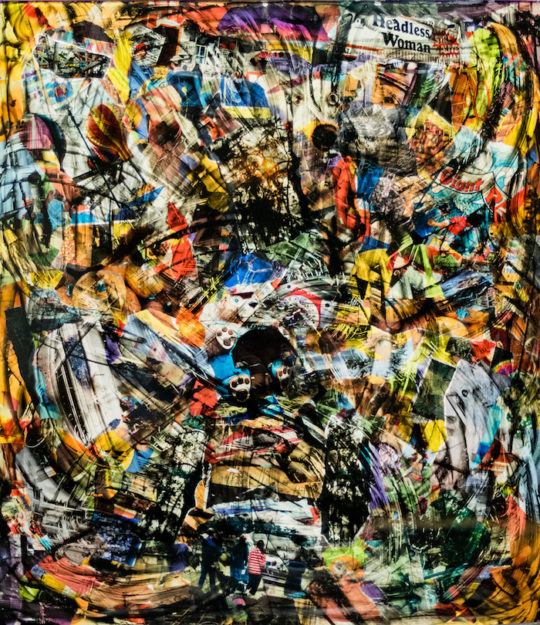

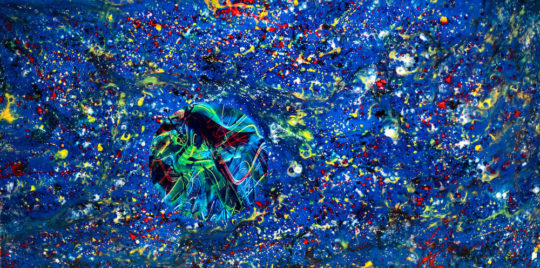

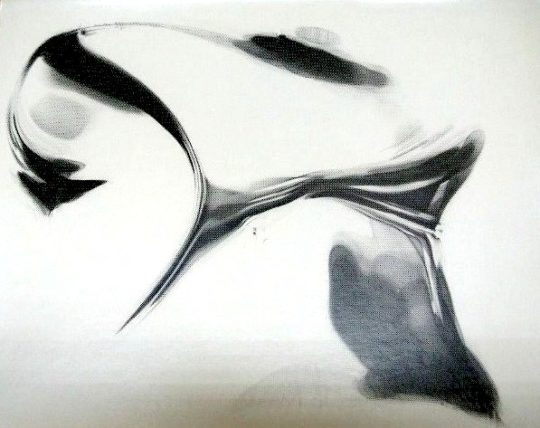

Living alone, McNease poured his energies into his art, moving freely between photography and painting as he dove deeper into abstract expressionism. He invented a unique technique in a process that began with painting individual brushstrokes as well as pouring swirling acrylic pigments on glass and letting each dry separately. He would then scrape them off, building up a huge supply. Finally, he returned to select from the individual dried brushstrokes, arranging and affixing them to a support material such as glass or wallboard. The resulting paintings looked as if they had been directly painted on canvas but in reality the final works are collages resulting from the transference of hundreds of dry acrylic brushstrokes. In consideration of the widespread adoption of acrylic pigments by the mid 1960s, it seems predictable that artists would eventually experiment with its pliable qualities.

Today this technique is known as painting with “skins” but during the early 1980s its earliest adopters were completely unknown to each other. Among these painters was Michael Gallagher [b.1945] who recently recalled to this author that his discovery of the technique happened in his Soho studio in 1979. “One day I was surprised to find that when cleaning up my studio floor some large splatters and blobs of dried paint released from the plastic film used as a drop cloth to protect my floor. I don’t know of anyone who was using the technique before me.” Perhaps the best-known artists also using the technique at this time were Frank Owen [b.1939] who exhibited them at the Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York in 1979; and, a few years later Jack Whitten [b.1939] was working with skins. None of these four pioneering peers were aware of each other, yet each also invented special tools for creating their skins in multiple swirling colors. One is hard-pressed to find others from that era, but the technique of skins is well-known today and encouraged by the big manufacturers of acrylic pigments.

True experimentation leads to no conclusion but the next step up the spiralling indeterminate ladder of creation.

— from the McNease Archive, May 2012

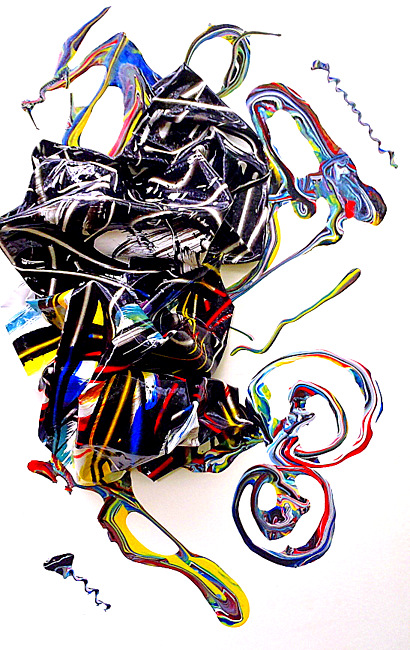

When painting on glass, McNease would often apply the brushstrokes to the reverse side — recalling the popular 18th century technique of verre églomisé, or reverse glass painting. He also created numerous free-form painting-sculptures with large sheets of acrylic pigments. Layer upon layer of pigments were painted on large sheets of glass. While the paint was still not fully dry, he peeled off the thick but pliable acrylic sheets and hung them loosely over objects where upon fully drying they became free-form sculptures. These works abandon the concept of canvas on a wooden stretcher and frame. Instead, they recall the spirit of Sam Gilliam’s free-form canvases of 1965–1975. McNease kept some of these painting-sculptures in his work sheds while he hung other pigment sheets over branches in the swamp, thereby bringing his art into a direct embrace with Nature. One of his mantras was “Emphasis is on process with nature as the source.”

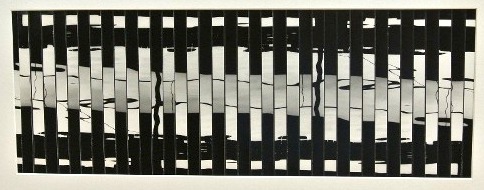

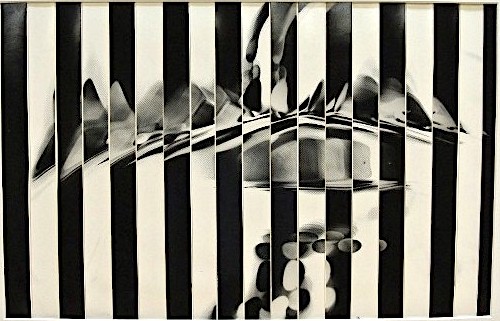

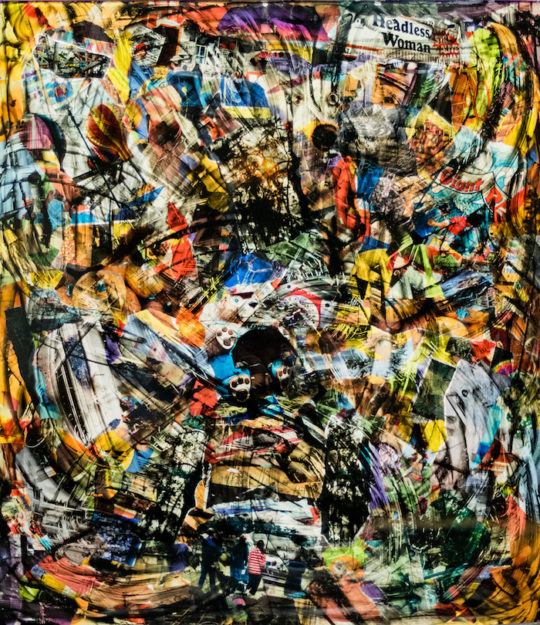

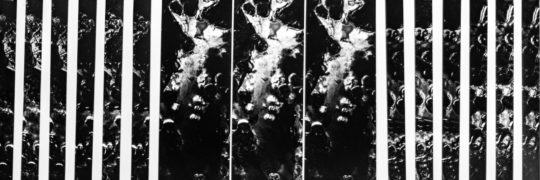

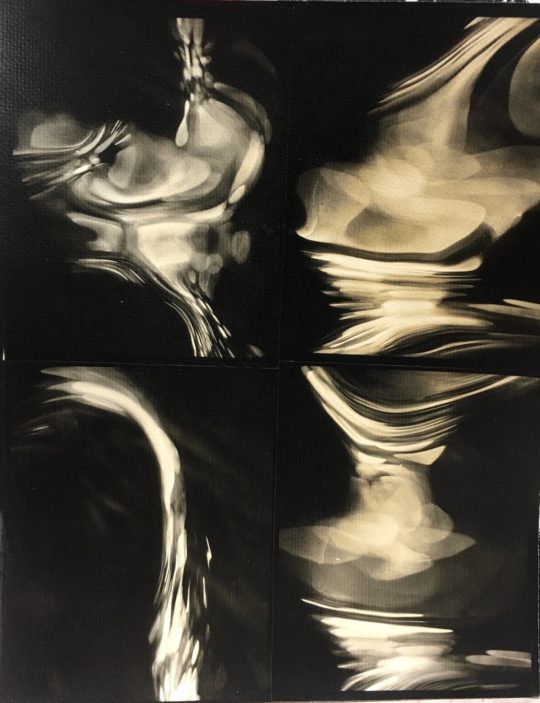

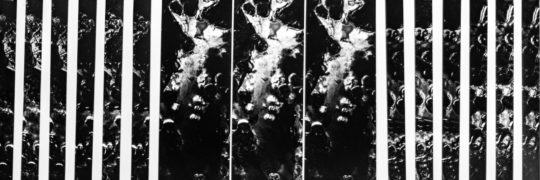

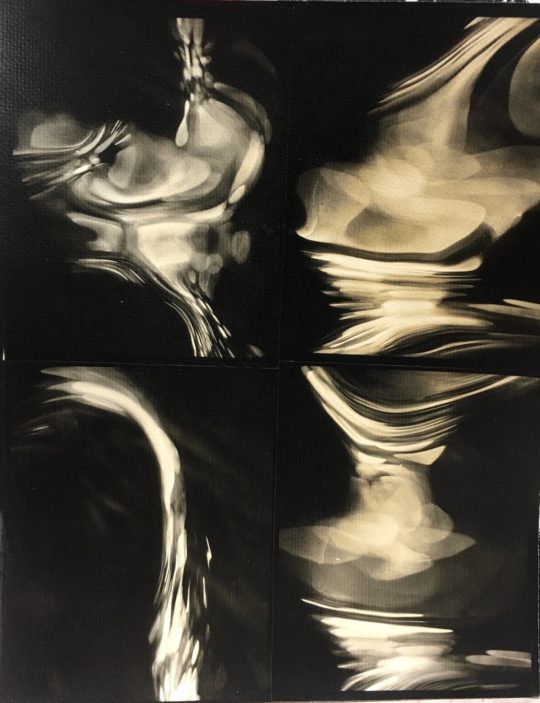

McNease constantly explored abstraction, moving effortlessly between — and merging — photography, painting, and sculpture. His foray into collage had begun in the early 1980s and was expanded with a mature series in 1989–90. With great precision and planning, he cut his larger photographic prints into long thin strips and rearranged them as rhythmic abstract images. His predecessors in such pure abstract expressionism in photography include Francois Bruguière, a painter who in 1912 first cut, arranged, and then photographed his paper abstractions under controlled lighting. Henry Holmes Smith, who taught at Chicago Bauhaus, produced cameraless abstract images. In the 1950s Lotte Jacobi also created cameraless prints she called photogenics. Aaron Siskind’s images of graffiti, peeling paint, and worn posters established him as the preeminent photographer associated with Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. But McNease’s carefully composed strips of photographs break new ground and generate a flow between photographic techniques and new painting techniques.

In 1984 the artist remarried, and together they purchased an old hunting camp in Perlington, Mississippi, where the Mulatto Bayou meets the East Pearl River. Straight across the river from their camp was the Honey Island Swamp Marina. “Not a more perfect place on earth to dwell,” declared McNease. There he continued to create photo-collages as well as develop his brushstroke transfer process on glass and other supports, almost always finding materials at low or no-cost. For example, on January 14, 1996, he wrote:

Forgot to mention in my last dreary passage…hundreds of sheets (40.5 cm x 25.5 cm) of glass scored! Karen, in her (fortunate for me) constant vigil, discovered a store in the outlet center (where she manages a store) going out of business. With great attention to detail and diligent awareness, the glass (actually shirt cubes) was procured — at no cost!!! So, there was a bright spot in an otherwise dismal week — six pickup truck loads. Amazingly, all materials (other than paint, etc.) over the past 3 plus years were obtained from that outlet center (signs, bulbs etc.). Obviously, money is, and should never be, no impediment to creation. If the need is there, there is a way.

In 1997, his wife was diagnosed with bone cancer. For the next two years his art production stalled, as he became her primary caregiver. Relatives said that her death in 1999, coupled with that of his mother, led him to become even more reclusive and eventually agoraphobic. In what was his last transition, he moved back to the two-acre Porter’s River Home Place located on the fringe of Honey Island Swamp near Pearl River in eastern Saint Tammany Parish. Increasingly, he took to the water in his kayak, birdwatching, fishing, and camping — and wrote about protecting the bayou environment that he credited as the wellspring of his creative inspiration. He was adamant about “Man’s systematic destruction of the planet earth.” A poet and philosopher, he left behind hundreds of pages of his writing on art, life, and the cosmos. Fortunately, he also carefully numbered and documented each artwork in a series of notebooks.

On August 29, 2005 Hurricane Katrina made its final landfall at the mouth of the Pearl River, pushing a storm surge up the river and through the bayou. Eschewing the warnings of authorities to move to higher ground, McNease was undaunted. Committed to experiencing the full force of nature, and despite the obvious danger, he managed to convince a neighbor to chain him to a post on his property and not unbind him until after the hurricane had passed. In the driving rain, winds of 120 mph toppled trees around him while brush and branches beat his body for hours. As the river water rose all round him, the artist was exuberant. He later wrote, “Chaos, after all, is the nature of abstraction as abstraction is the nature of chaos.”

In January 2009, McNease explained why he chose to live and create in isolation:

No longer have much contact with the outside art world in particular. Mostly contact and dialogue with Nature.

But that doesn’t tell you much, does it? Quite some time ago, over 20 years now, I did the “usual” things one does in art — the shows, collections — all over the country, and particularly with photography. But that road can quickly lead to a “loss of meaning” if one is not careful — becomes “about the artist” rather than “about the art.” So I left that scene to develop my art, self, and particularly pursue a long held idea of mine — to see and view the world in the eyes and mind of the feral child.

Thus, new thought, new idea and new technique. Had to invent techniques to go with ideas — and definitely did not wish to incorporate idea-technique from previously developed art. My paint transfer technique allows complete control over the paint (though the imagery may well not show this). One can transfer to any mount, cut it, tear it, shape it, use it with other sources (mixed media), attach to armatures and hang as mobiles and on and on — a virtually unlimited “technical palette.”

On October 23rd, 2014 McNease suffered from an acute and extended bout of abdominal pain. True to his nature, he refused to make the trek to town and see a doctor. Writhing in his bed, the pain became so unbearable that he finally drew his gun… and shot himself. The coroner later determined that the source of his pain was a ruptured gallbladder.

After this final tragedy, the McNease family carefully preserved the artist’s collection and archive. In hindsight, McNease had enjoyed the most encouraging launch into the art world in 1975, winning critical recognition for his photography. However, in 1983 his divorce also served as the catalyst for his complete immersion — and ultimate isolation — in the natural environment of the swamp. There his work morphed between photography and painting, and he invented an entirely new technique of pigment transfer. It was in the bayou that this Outsider became one of the more innovative artists of the late 20th century. As a “feral” artist McNease remained “Free of the constraints of any particular wisdom or attitude. Free, yes free, of set belief or idea as such has no true existence in the ever-changing world of nature.”

Ultimately, McNease was steadfast in fulfilling his noble quest:

“Transcendent Expressionism: The simple creative logic of rising above and beyond ordinary limits or experience. Not dogma, not philosophy, but the simple process of idea, mind, art (creativity) in progressive evolution along infinity’s path.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Unless dated, the artist’s quotes are from the McNease Archive, most from 2012

The Feral Abstract Expressionist of Honey Island Swamp

-

DETAILS

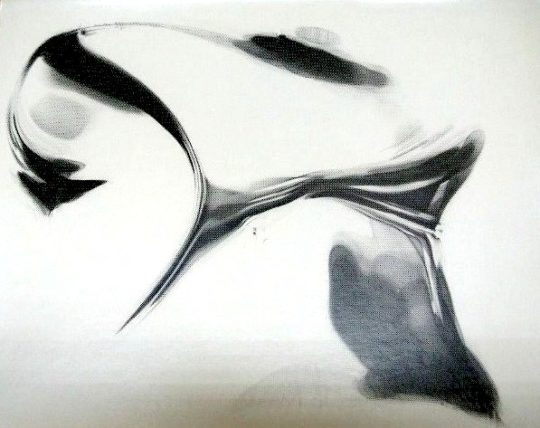

DETAILSAbsorbed by the Reason of Truth, 1986

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

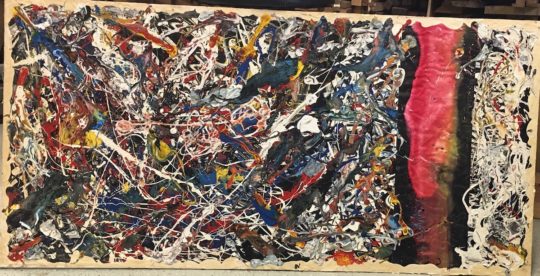

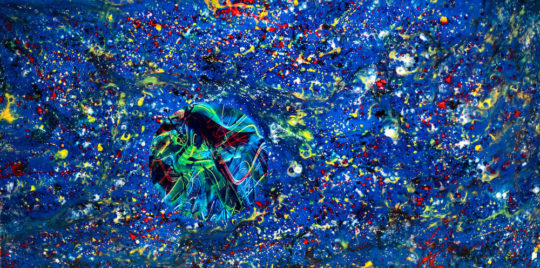

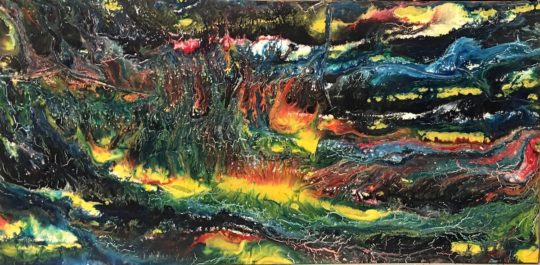

DETAILSAnd Eden Burns, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAnd The Evening Was Without Rain, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

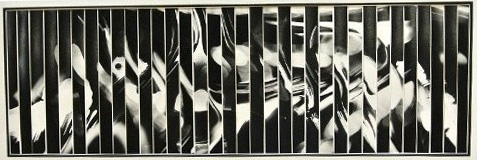

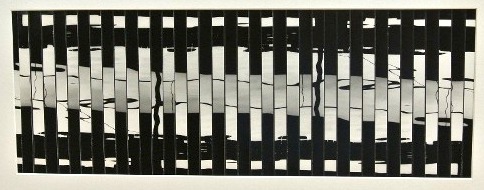

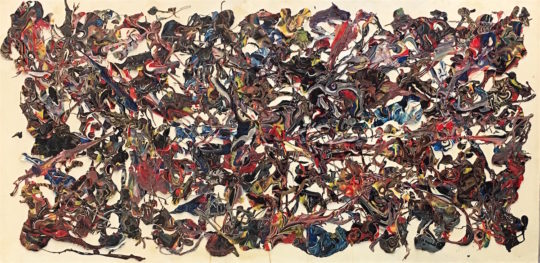

DETAILSAtoral Movement, 1989

12 x 38 inches (30.48 x 96.52 cm) -

DETAILS

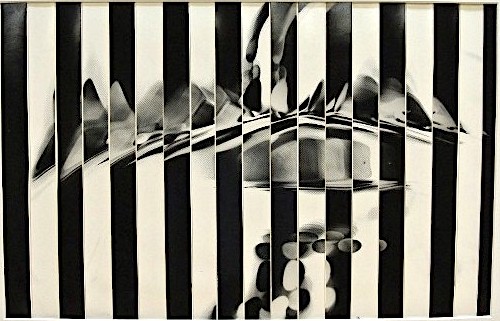

DETAILSBy Which…By Which, 1989

12 x 20 inches (30.48 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

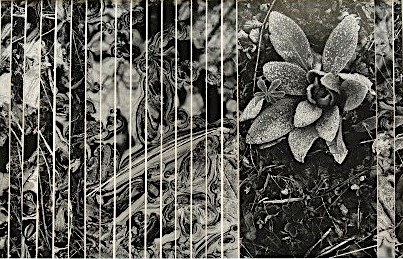

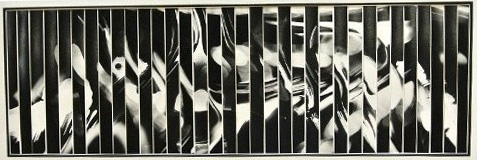

DETAILSDisparity, 1989

12 x 38 inches (30.48 x 96.52 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEncountered Briefly, 1986

14 x 24 inches (35.56 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFlow through what spatial unknowns of dimension?, 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFreedom’s Gate: Chaos and the Miracle of Myth, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

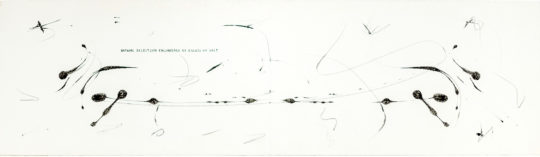

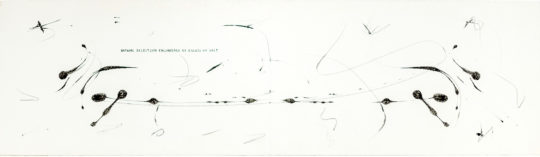

DETAILSNatural Selection Encumbered By Excess Of Salt, 1995

8 x 24 inches (20.32 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNo Stronger Than The Weakest Link, 1998

21 x 25 inches (53.34 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSingularity, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Empress Wore Shiny Clothes, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Importance Of Assimilation, 1994

14 x 28 inches (35.56 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

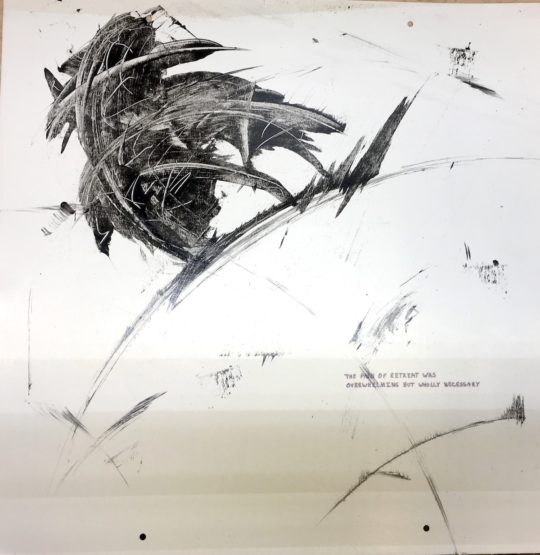

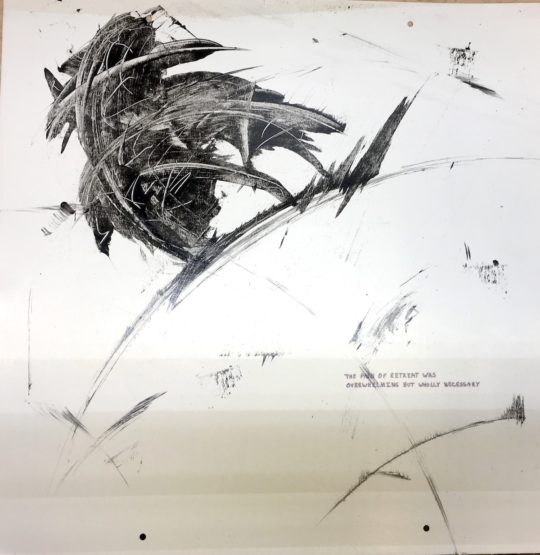

DETAILSThe Pain of Retreat, 2000

20 x 20 inches (50.8 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Paint Has But No Recourse But To The Page, 1997

12 x 14 inches (30.48 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

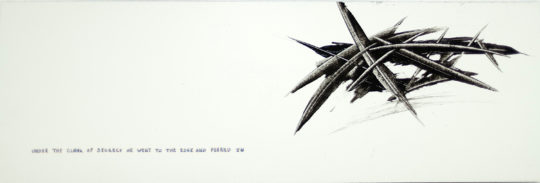

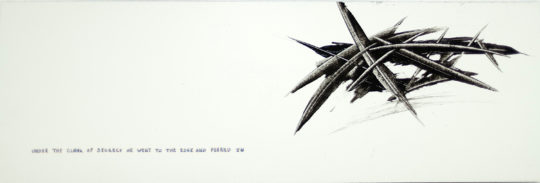

DETAILSUnder The Cloak Of Secrecy He Went To The Edge And Peered In, 1995

8 x 24 inches (20.32 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnititled, 2000

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnititled, 2000

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnititled, 2000

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

16 x 10 inches (40.64 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

16 x 10 inches (40.64 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

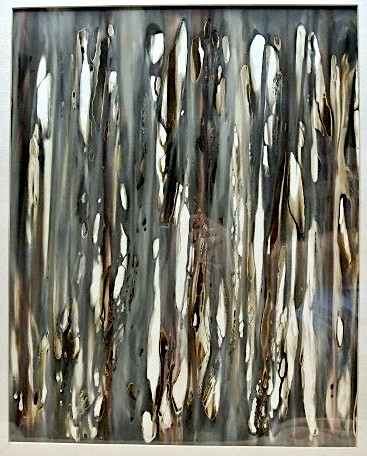

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

25 x 21 inches (63.5 x 53.34 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

25 x 22 inches (63.5 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

16 x 28 inches (40.64 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

56 x 26 inches (142.24 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1989

8 x 24 inches (20.32 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1989

13.5 x 21.5 inches (34.29 x 54.61 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

16 x 26 inches (40.64 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1998

41.5 x 10 inches (105.41 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1986

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1998

56 x 26 inches (142.24 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

18 x 10 inches (45.72 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1977

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1977

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

18 x 20 inches (45.72 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 36 inches (50.8 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 18 inches (50.8 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 18 inches (50.8 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 18 inches (50.8 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

18 x 28 inches (45.72 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (4490), 2000

20 x 48 inches (50.8 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

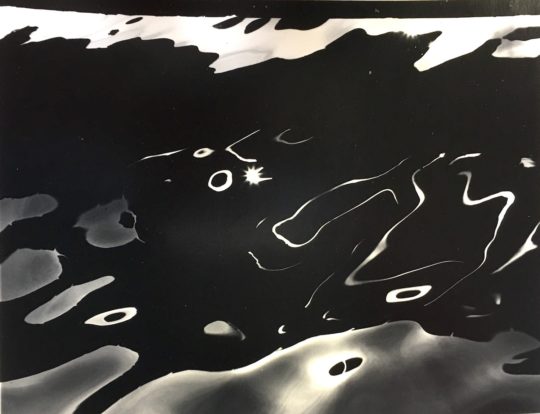

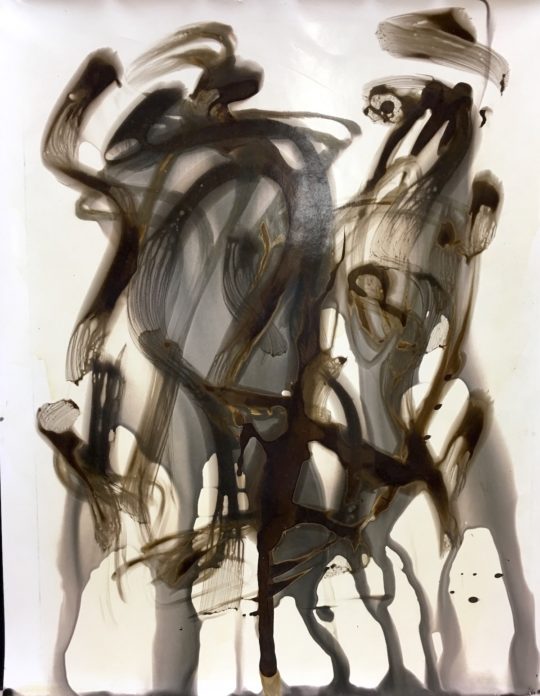

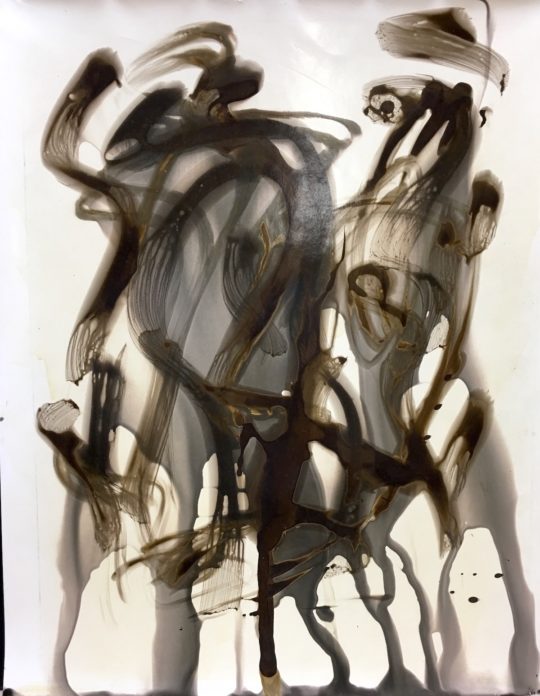

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Ice Series), 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Photomontage Series), 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled Abstraction, 1986

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled silverprint, 1977

17 x 14 inches (43.18 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled silverprint, 1977

14 x 18 inches (35.56 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, from the Chemigram Series, 1983

19 x 15 inches (48.26 x 38.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, from the Chemigram Series, 1983

20 x 24 inches (50.8 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, from the Chemigram Series, 1983

19 x 15 inches (48.26 x 38.1 cm) -

DETAILS

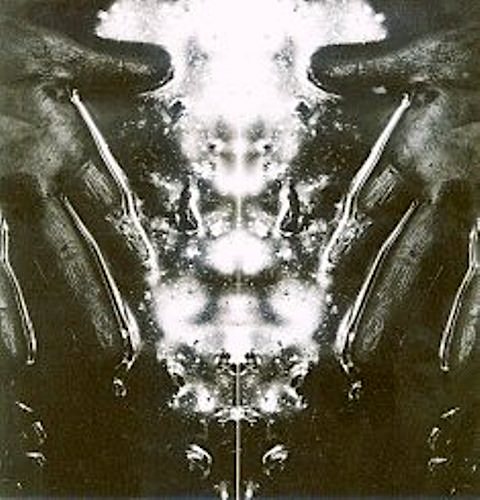

DETAILSVisages — Ariel, 1989

24 x 24 inches (60.96 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWalls crumble to fearless tears…Remember…Once, Remember, 2000

20 x 48 inches (50.8 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

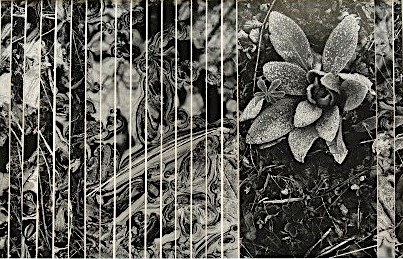

DETAILSWhat Is It That I Am? And I Am Not?, 1990

13.5 x 21.5 inches (34.29 x 54.61 cm) -

DETAILS

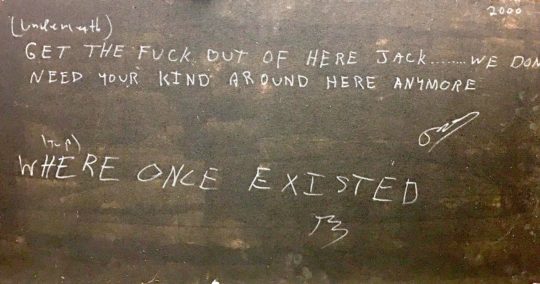

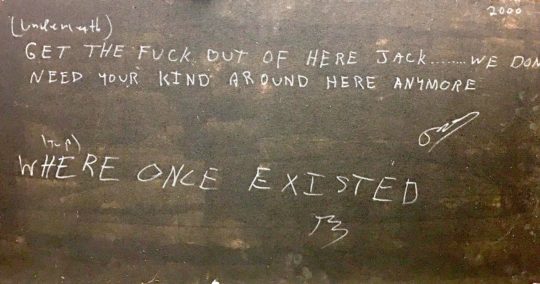

DETAILSWhere Once Existed, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhere Once Existed (detail), 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhere Once Existed (verso), 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSAbsorbed by the Reason of Truth, 1986

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAnd Eden Burns, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAnd The Evening Was Without Rain, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAtoral Movement, 1989

12 x 38 inches (30.48 x 96.52 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBy Which…By Which, 1989

12 x 20 inches (30.48 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDisparity, 1989

12 x 38 inches (30.48 x 96.52 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEncountered Briefly, 1986

14 x 24 inches (35.56 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFlow through what spatial unknowns of dimension?, 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFreedom’s Gate: Chaos and the Miracle of Myth, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNatural Selection Encumbered By Excess Of Salt, 1995

8 x 24 inches (20.32 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNo Stronger Than The Weakest Link, 1998

21 x 25 inches (53.34 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSingularity, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Empress Wore Shiny Clothes, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Importance Of Assimilation, 1994

14 x 28 inches (35.56 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Pain of Retreat, 2000

20 x 20 inches (50.8 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Paint Has But No Recourse But To The Page, 1997

12 x 14 inches (30.48 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnder The Cloak Of Secrecy He Went To The Edge And Peered In, 1995

8 x 24 inches (20.32 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnititled, 2000

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnititled, 2000

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnititled, 2000

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

16 x 10 inches (40.64 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

16 x 10 inches (40.64 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

25 x 21 inches (63.5 x 53.34 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

25 x 22 inches (63.5 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

16 x 28 inches (40.64 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

56 x 26 inches (142.24 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1989

8 x 24 inches (20.32 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1989

13.5 x 21.5 inches (34.29 x 54.61 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1996

16 x 26 inches (40.64 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1998

41.5 x 10 inches (105.41 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1986

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1998

56 x 26 inches (142.24 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

18 x 10 inches (45.72 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1977

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1977

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

18 x 20 inches (45.72 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 36 inches (50.8 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 18 inches (50.8 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 18 inches (50.8 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

20 x 18 inches (50.8 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2000

18 x 28 inches (45.72 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (4490), 2000

20 x 48 inches (50.8 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Chemigram Series), 1989

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Ice Series), 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled (from the Photomontage Series), 1977

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled Abstraction, 1986

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled silverprint, 1977

17 x 14 inches (43.18 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled silverprint, 1977

14 x 18 inches (35.56 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, from the Chemigram Series, 1983

19 x 15 inches (48.26 x 38.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, from the Chemigram Series, 1983

20 x 24 inches (50.8 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, from the Chemigram Series, 1983

19 x 15 inches (48.26 x 38.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSVisages — Ariel, 1989

24 x 24 inches (60.96 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWalls crumble to fearless tears…Remember…Once, Remember, 2000

20 x 48 inches (50.8 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhat Is It That I Am? And I Am Not?, 1990

13.5 x 21.5 inches (34.29 x 54.61 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhere Once Existed, 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhere Once Existed (detail), 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhere Once Existed (verso), 2000

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

No Events Found.