In Search of Herself: The Art of Reva Freedman

— by Gary Monroe

My mother spent most of her life trying to stay young. — Sue Felner

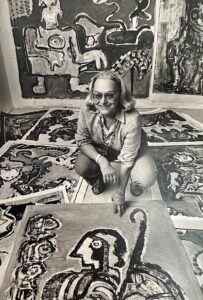

Reva Freedman found her meaning through painting. An unending verve set her free to discover her aesthetic and herself. Her art is not a matter of patterns and textures, but rather one of life and death. In a critique of her art, to say that color inspired Reva Freedman is about as useful as saying one loves nature; it trivializes, if not misses, the point. Hers are not color field paintings or art-for-arts-sake creations but are investigations into her own psyche. Since she started painting late in life, it is not quite right to say that art- making was a function of her becoming. She was already who she had become; her painting was likely a primal scream because of it.

Reva Ralston was born in Toronto, Canada on January 9, 1919, to Jewish immigrants; her mother was from Romania and her father from Poland. Her parents were hardworking people who early on recognized her musical talent. Reva became a child prodigy and was recognized for having perfect pitch; she performed with the Toronto Philharmonic at the age of 13. According to her daughter, Sue Felner, “she didn’t have much of a childhood” to which she adds, “maybe that’s where her paintings came from.” That’s hard to know, but Reva Freedman seemed to express existential qualities through painting. Her process revealed archetypal forms; hers are not decorative abstractions. This is a lofty notion for sure but how else to identify the ineffable quality of art that exists with a shamanistic presence?

Growing up, Reva “lived in a world by herself.” She felt alone. She wasn’t without art, though. She loved music but she didn’t have much else. Reva was tough, a fiercely independent thinker who rebelled against authority and had no patience for conformity at any point during her life. Her son, Ron, points out that “the time she spent painting was the only time that she seemed to be truly at peace, with nothing to prove to anyone.” It was also the only time she felt heard; seemingly this–being heard–was at the root of her loneliness. Reva’s interest in music began to blossom at age six, playing the piano and, two years later, the violin. She discovered the potential that painting held for self-expression, or for being heard, in middle age.

As a youngster, with next to no social life, Reva, was always practicing her violin. She loved to read, even the dictionary just to learn the meanings of words. At school, Reva was petrified of spelling words aloud; she would rather fail the course than participate and be noticed. However, she did not cower from performing on stage alongside other musicians; she loved that. But music did not satisfy her longing; it didn’t provide the kind of “being heard” that Reva longed for. She went unnoticed and this was fine with her overprotective mother. She even wore nondescript saddle shoes; she wasn’t to standout. If Reva dated, it was chaperoned. “Her mother used to sit in another room that had a glass window between them and watch what went on; she was the disciplinarian,” points out Sue.

As a youngster, with next to no social life, Reva, was always practicing her violin. She loved to read, even the dictionary just to learn the meanings of words. At school, Reva was petrified of spelling words aloud; she would rather fail the course than participate and be noticed. However, she did not cower from performing on stage alongside other musicians; she loved that. But music did not satisfy her longing; it didn’t provide the kind of “being heard” that Reva longed for. She went unnoticed and this was fine with her overprotective mother. She even wore nondescript saddle shoes; she wasn’t to standout. If Reva dated, it was chaperoned. “Her mother used to sit in another room that had a glass window between them and watch what went on; she was the disciplinarian,” points out Sue.

As a Jew living in a non-Jewish community in Toronto as World War II brewed, her family faced anti-Semitism. “She was one of three Jewish kids in her grade school,” explains Sue. This further foisted Reva into a void, living in her own alienated world. She was alone and perhaps felt targeted. “She spent a lot of time hiding,” says Sue, adding, “She didn’t have an identity when she was young.” Reva was without friends.

Reva graduated from the Toronto Conservatory of Music. She played in the Promenade Symphony of Toronto and the Toronto Philharmonic Orchestra. While performing in the Catskills in upstate New York, Reva met her future husband, Morris Freedman. He was a soldier at the time and was attracted to her physical beauty as well as her violin playing. He admired her confidence and multiple skills while providing her the freedom to do anything she wanted; his support would have a great impact on her art making.

They married in 1944 and moved to Laurelton, Queens, and soon afterwards relocated to Great Neck, Long Island. “She played housewife,” Sue explains, “playing bridge, having a social life, and raising three children.” Reva continued playing violin and viola in the Long Island Symphony, where she performed as a soloist and played in chamber music groups. When she was not playing music, she was introducing music to her children’s lives through lessons and concerts. She was an avid reader and interested in current events. She enjoyed visiting art museums and hunting for antiques.

Sue and her siblings agree that their mother concealed her emotions, rarely expressing or sharing her feelings. Reva had a lifelong obsession–a fear of aging. The only time she was seen shedding tears was over a song about getting old. “Do you know how many years we lived with my mother before she told us how old she was?” Sue exclaims, adding, “She wanted to stay young.” Reva never told her children her age. That’s something she would never have shared. They only learned her age while helping with her financial affairs; they needed to get her birthdate for insurance, social security, and related purposes. She was in her early eighties then, at least on paper. Reva was young at heart.

Her outlook on life was all about spirited living. She observed that children had all the freedom; they lived free of other people’ s whims. She looked at older people as being very stuck in their ways, seeing things as having to be a certain way. As Reva Freedman aged, she wore clothes that young people wore; her hair was straight and blond, and pushed off her face by a headband. She felt that creativity was the domain of youth, so she fashioned herself–mind, body and soul–in that way.

Annual trips to Florida provided Reva with a reprieve from cold New York winters. The family vacationed, as many Jewish families did, in Miami Beach. Hotels then offered poolside activities. Guests could take dance lessons, play Bingo, and get art instruction. During a vacation in 1961 at The Barcelona, a swanky hotel by the famed Fontainebleau, Reva participated in a painting class. She was forty-two years old at the time and this proved to be an event that would shift her life focus. Years later she was featured in a Miami Herald article (April 26, 1987) about that fateful day saying, “We were supposed to paint a photograph of a barn. I kept changing it. I made the barn disappear and turned it into a mountain. I felt like this was the most exciting thing and I was hooked. I’d had a misconception of what art was. I thought you had to have a natural ability for drawing when you were young. I didn’t have that.”

The snowbirds relocated to Miami as retirees in 1974. Soon Reva would become an original painter and fulfill her creative ambitions, or at least find solace through painting. Her alienation would become solitude, and immortality would be on the horizon. Painting would at least offer an unbridled expression for acknowledging her self-worth. No longer would she be restrained. She would become herself. The days of being co-dependent on a conductor and other musicians were past. Making music was a form of self-expression but it required structure, and this was like having brakes with someone else at the wheel. She was tied to technique with her musical instruments. Reva intuitively knew that technique could stifle creativity, as had been the case for her. She wanted to be in the driver’s seat and hit the accelerator. If she could not stay forever young, she could at least live freely and fully while creating a lasting testimony.

Painting meant freedom and she was hooked. Reva could not get the sense of abandon and revitalization from playing music that she got from the visual arts. She enrolled in formal art classes, but these were not satisfying; before long she was rebelling against her teachers’ parochial ways. She didn’t care to fit in or go along to get along. Something was itching; she was searching to express herself without the reserve of tradition. Reva still craved immortality but would gladly settle for attention and appreciation in the meantime, while she shed others’ influences.

“When I say that my mother drove everyone crazy, I mean that she broke the rules,” clarifies Sue. If anyone marched to the beat of his or her own drummer, it was Reva Freedman. She did not like to take “no” for an answer and would keep asking the same questions until she got what she wanted. She painted the way she wanted to, to her teachers’ chagrin. She acted like most teachers did not know what they were doing because they all talked, thought and painted similarly. She didn’t hesitate to say what she thought about people and situations either, even if it caused hurt feelings. “She wasn’t so extreme earlier in her marriage. She became more like this after her children grew up and were out of the house,” adds Sue.

Art making would be a refuge, where Reva reclaimed her youthful vigor. Perhaps it was her palace, where she could rule without restraint. Reva could be carefree, lost to her art. She could be herself through the process and she must have known this was a prerequisite for creativity. She no longer had to hide, no longer had to be a wallflower. She couldn’t hide because the paintings revealed all, codified as they were. Suddenly the girl who went unnoticed was exposed. She was impossible to miss. Her art, like her music, was an escape and gave her the ability to recreate her life. “She did not choose to see herself as a victim and alone, that is why she escaped into her world of creativity,” offers Sue.

Reva at first played with different stylistic approaches. She collected artists’ monographs and emulated Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, Willem De Kooning, Jackson Pollack, Joan Miro, and Red Grooms but would quickly arrive at her own way of painting. She disregarded the styles of others rather than synthesize their influences. Their content was established; Reva was in search of substance, and it emerged full-blown. She believed that anything could be art and experimented with different media, even checking in front of homes for things that people were throwing away that might be recycled and integrated into her own creations. She became fascinated by how many ways she could paint the same thing so that all the iterations held different meanings.

Reva’s artwork became less and less referential to any subject and any genre, while her paintings became increasingly wilder. She would claim as useful many things that others would hardly consider. She incorporated traditional and non-traditional material into her pieces: tar paper, canvas, watercolor paper, burlap, sketching paper, acrylic paint, oil paint, tempera, watercolor, markers, foam, newspaper, duct tape, scotch tape, aluminum, foil, towels, hair, wood, bark, name tags, napkins, comics, magazines, ribbon, felt, fabric, ink, wallpaper, jigsaw puzzle pieces, chalk, pastels, t-shirts, glitter, puff paint, masking tape, cardboard, glue, ink pens, paper plates, candy wrappers, cellophane paper, and coffee can labels. She painted “like a wild woman, looking for a fix slopping paint left and right, the brighter the better,” as she described it.

Reva also fashioned sculptures from Styrofoam. Her abstracted scenes made by assembling odd, shaped pieces used to pack and ship merchandise were like dioramas from another world. “Each of Reva’s Styrofoam creations looks as though it may have been born purely of form. But on closer inspection one contains timepieces that are reminiscent of Dali, another has animals at the circus, perhaps an ode to Calder. Some display the playfulness of Red Grooms. One can continually explore each piece to find something new, true to Reva’s own mantra on life,” suggests Annette Ricciardi, Reva’s daughter-in-law.

Although Reva wanted to learn everything, she could about the technical aspects of art in studio workshops, she quickly abandoned this pursuit as a prerequisite. She vanquished dogma and conventional thought. She went about corrupting the staid compositions made in early figure drawing classes by altering the otherwise predictable sketches as a kind of deconstruction, if not out of sheer curiosity. According to the 1987 Miami Herald article she stated, “My style is to try to be fast and trust your instincts and don’t fuss over every little thing.”

Reva stood for individuality. She said that everyone saw the same thing differently so no one should teach people to see any one way. Technique was only a starting point for her; though it is not quite right to say that she went about breaking the rules, for she never really learned them. That is, Reva rejected the conventions her teachers were instructing from the start. She had no room for theory. She told her children that any colors go together. “I was the only one in my school wearing reds with yellows,” chuckles Sue. Ron points out that Reva took up golf late in life, at fifty. She played barefoot and insisted on hitting from the men’s tee! She reveled in their shock and awe.

Reva became more and more obsessed; she was soon painting day and night. Her condo in Aventura in northern Miami-Dade County became a big artist’s studio. Paintings in progress and completed ones were tacked everywhere, hung one above another while many more were stacked in closets so that they would often cavalcade out when the door was opened. She often worked on five paintings simultaneously. Ron points out that it was “like someone playing multiple cards to improve their odds of winning at Bingo.” If she were in a painting rage and came across a completed painting, she might paint on that one as well.

Like call-and-response field hollers, Reva defined the paintings through a give-and-take process. “Smear it a little here, I smear it a little there,” she explained as she brushed and sponged florescent colors across large sheets of tar paper that were tacked onto her walls in every room–living room, dining room, bedroom. Her labor found cohesive and resonant forms through an intuitive act of painting. She was again living in the world alone, but this time it was by her own volition. She was an artist. Like most artists who are beyond illustration, she was given over to her art and worked feverishly to see what the next piece would yield. She finally had a meaningful life, one in which she found her groove and her mission.

In 2001, Reva’s husband Morris began to suffer at an accelerated pace from Parkinson’s disease. Reva was distraught over Morris’ failing health and how it might affect her artwork. She wrote a grant request mentioning her husband’s poor health to get people to fund and show her painting. It was a ploy; money was never an issue. Nevertheless, when Morris was sick, Reva plunged even deeper into art making. Music and painting provided her with a diversion from the unhappiness she was experiencing with his illness. “Her art and music was always an escape to the world she wanted to be in,” Sue points out. It was a loving marriage. Morris was always supportive of Reva’s need to create and respectful of her individuality. Ron says, “My father, Morris, even hand-crafted wooden frames for Reva’s paintings.”

Although many people in the family did not understand Reva because of how different she was, she, in turn, got along well with them because she knew how important family was to Morris. Artistically, although Reva desired being the center-point of gallery openings, the interactions with energetic young artists, and the contentious encounters with the old guard, she worked in relative isolation.

A year later Reva was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. “She started exhibiting strange behaviors,” Sue says. Her behaviors started to change after Morris passed away, “they became extremely erratic.” The couple had been married for fifty-seven years. “My mother had been devoted to my father when he had Parkinson’s disease and would push him to participate in her quartet concerts at the library and in the art shows she had,” says Sue. Now she was alone with an apartment full of her paintings.

Sue theorizes that her mother’s physical and mental decline began with an untreated blood condition, and that her health ills were exacerbated by toxicity of the paint. Reva painted in her cocooned air-conditioned apartment often through the night and fell asleep exhausted and covered with paint. As Reva’s health failed, she painted even more manically, stacking paintings upon paintings throughout her apartment, under her bed and on top of furniture, and even spread out across the floor.

Reva Freedman passed away on March 29, 2011, but not before realizing her central aspiration. Her paintings hung in six Norton Museum of Art’s Hortt exhibitions. Inclusion in this prestigious annual juried show was a source of pride. Her paintings were recognized with a one-person exhibition at the Hollywood Art and Culture Center in 2002. This she surely felt was a sign of arrival. She was represented in other regional group exhibitions. “The recognition was everything she was looking for,” says Sue, who now serves the family as their mother’s archivist, caring for and promoting her life’s work consisting of some 1200 paintings.

Before the millennium, so-called Outsider artists set the established art world ill at ease; experts all too often didn’t quite know what to make of their renegade creations. Everything was done wrong by these irreverent self-taught art makers, at least from an academic point of view, and their work was seen at arm’s length if seen at all. Yet their paintings and sculptures addressed what is generally most valued in art–a transcendent sense of self. And the work was beautiful, though different. It’s a bit ironic that this art hit a wall with the museum culture then, when it is precisely these arts leaders who are charged with recognizing, supporting and expanding the definition of art as an evolutionary practice.

Today, the virtues of self-taught art and these artists’ best works have been coopted and integrated into that rarefied world. They are exhibited without reservation by fine art museums, and this is largely because Outsiders have contributed to the dialog of what art might be. Reva Freedman’s paintings are in the top tier of self-taught art, and I say this after having traversed Florida in preparation of writing Extraordinary Interpretations: Florida’s Self-taught Artists (University Press of Florida, 2003). I had met seventy men and women working in isolation, largely to satisfy their own muses. Monetary gain was not central to their make-up. They created because they had to.

Having begun art making at a time when women were just beginning to be accepted into the art world through rigorous academic training, Reva was intent on making her voice known as a largely self-taught prolific painter. Though she reveled in people’s delight of her artwork and the attention the few exhibitions that included her work brought, she was still an outsider working in obscurity. This was likely in her nature. She grew up alone, rejected convention and authority, and died feeling alone–at least as a fine artist.

Reva began writing in her sixties and much of the writing states how alone she felt. She felt like her children left her and none was interested in what she was doing with her life. Indeed, as she got older, she spent more time alone, decreasingly socializing. Sue points out “the alone part was that she felt alone and not heard.” In truth, Reva was not alone; her daughter Carol took care of her with loving attention. “She had the aides and my sister there all the time and they had many conversations with her. Carol researched and read everything she could to keep my mother present to the people around her,” Sue points out. It was loneliness that perhaps artists live and die with, a kind of solitude that results from knowing themselves and the world from their labor.

I think Reva Freedman tapped into something essential through abandonment by the way she painted. This allowed her to mine her own interior resources, to be in tune with the world, as it were. Her artwork was more about process than product; her paintings gained presence as if she were communing with cosmic forces. Once, about becoming a painter, Reva commented, “whatever I attempted seemed to have a life of its own… barns became mountains… roads turned into rivers and back again… amazing what a little paint could do. I felt like God. Who else could have moved scenery around like that?” Her paintings came to reveal more than they showed, and that aspect is a form of immortality, a legacy at least.

“Moreover,” writes Gabriel Rockhill in his essay Why We Never Die (New York Times, August 29, 2016), “the physical dimension of existence clearly persists beyond any biological threshold, as the material components of our bodies mix and mingle in different ways with the cosmos. The artifacts that we have produced also persevere, which can range from our physical imprint on the world to objects we have made or writings like this one. There is, as well, a psychosocial dimension that survives our biological withdrawal, which is visible in the impact that we have had–for better or worse–on all of the people around us. In living, we trace a wake in the world.”

Mr. Rockhill goes on to suggest that biological death is not necessarily the endpoint of our physical, artefactual and psychosocial lives. He contends that we live on by intertwining with the fabric of humanity over time. He concludes that “our immanent lives are actually never simply our own.” What Reva Freedman created took on a life of its own. Her artworks belonged to a woman channeling ancestral forces, and now they belong to us. Perhaps they were always ours. Nevertheless, her art is part of our identity.

To me, Reva Freedman was in a class all her own. She worked in a mysterious realm between consciousness and materialism. She was given fully to her labor, and it is as if her paintings are her DNA. Living life fully for one’s art is necessary to sustain and distinguish it. There can be no reservations or excuses or doubts about one’s commitment — one is all in. This unconditional quality was well suited for Reva Freedman because it leads to living internally, and she lived this way all her life. It is perhaps the difference between being adrift from being lonely. Maybe she was never really alone but driven. She had purpose; she knew where she was going. Her trove of paintings is proof of her arrival.

About the Author

This essay, originally published in Folk Art Messenger (Spring/Summer 2017, p.8-11), has been reprinted with the kind permission of Gary Monroe. The author of ten books about Florida’s self-taught and vernacular artists, Gary has given voice to overlooked and disenfranchised but creative people, and in doing so he has enriched our lives by introducing us to new ways of thinking about art and culture. His most popular title, The Highwaymen: Florida’s African American Landscape Painters, launched a cultural phenomenon and resurgent interest in these forgotten mid-century artists. Mr. Monroe writes articles and lectures widely; he may be reached through his website www.floridafolkart.net

Celebrating a Self-Taught Master

-

DETAILS

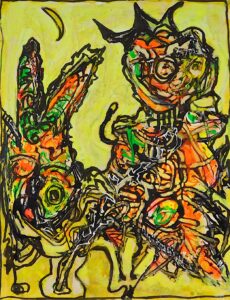

DETAILSTable Manners, 1985

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

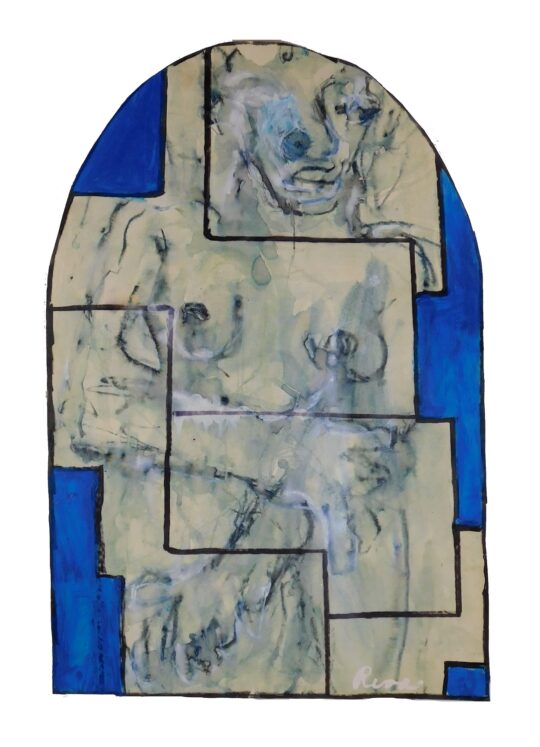

DETAILS

DETAILSTeal, 1980s

40 x 26 inches (101.6 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Girl With the Purple Stockings No.2, 1986

36 x 25 inches (91.44 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThrough the Window No.1, 1987

35 x 24 inches (88.9 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThrough the Window No.2, 1987

35 x 24 inches (88.9 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThrough the Window No.6, 1987

35 x 24 inches (88.9 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.3, 1994

47 x 36 inches (119.38 x 91.44 cm) -

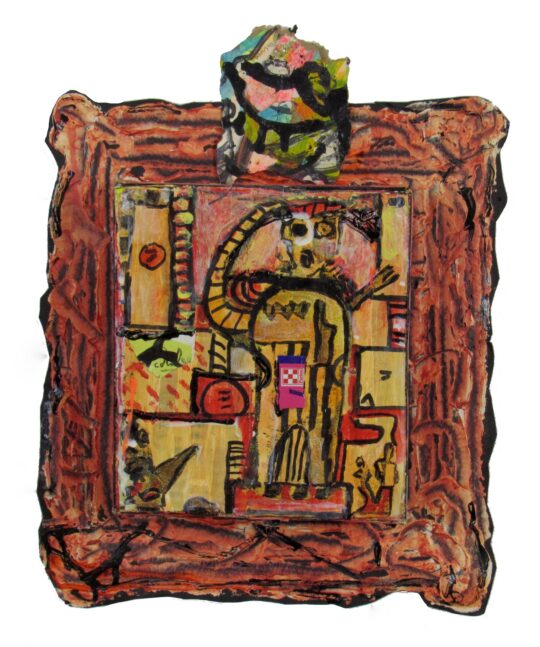

DETAILS

DETAILSStuck in the House, 1999

17 x 15 inches (43.18 x 38.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Bird Plume, 1980s

53 x 34 inches (134.62 x 86.36 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPlaytime No.1, 1985

25 x 33 inches (63.5 x 83.82 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPlaytime No.2, 1980s

23 x 35 inches (58.42 x 88.9 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSJungle Scene (A Moment in Time), 1980s

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Red Hat, 1980s

24 x 19 inches (60.96 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSManicure No.2, 1980s

24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Pumps, 1980s

20 x 15 inches (50.8 x 38.1 cm) -

DETAILS

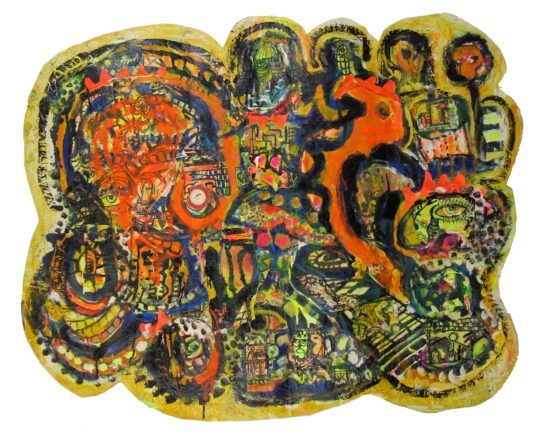

DETAILSAnything and Everything, 1980s

38 x 47 inches (96.52 x 119.38 cm) -

DETAILS

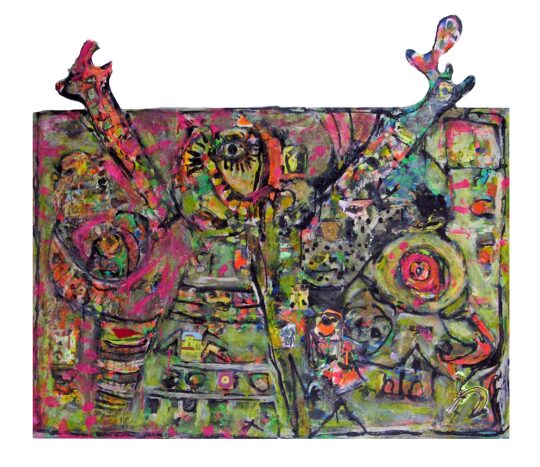

DETAILSPraise, 1980s

42 x 48 inches (106.68 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Evening News, 1985

26 x 19 inches (66.04 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

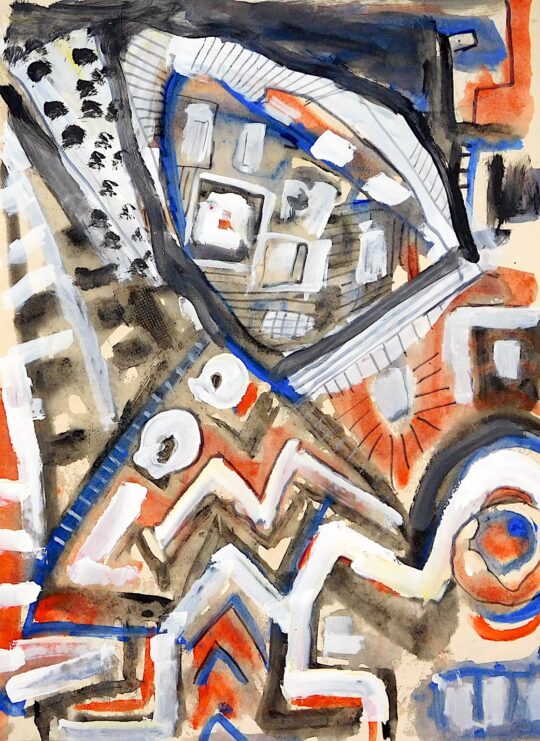

DETAILSMosaic No.4, 1980s

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

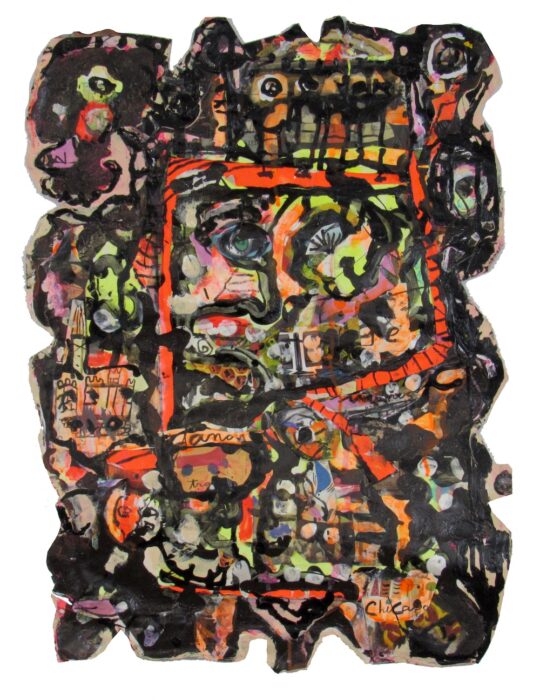

DETAILSTwo-Faced No.1, 1986

40 x 26 inches (101.6 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

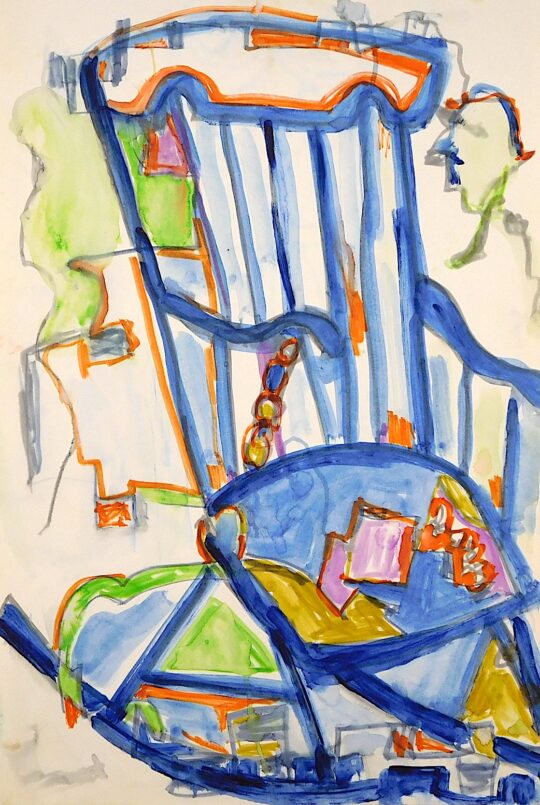

DETAILSOff Your Rocker No.4, 1999

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOff Your Rocker No.3, 1999

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOff Your Rocker No.5, 1999

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSHoops, 1986

26 x 21 inches (66.04 x 53.34 cm) -

DETAILS

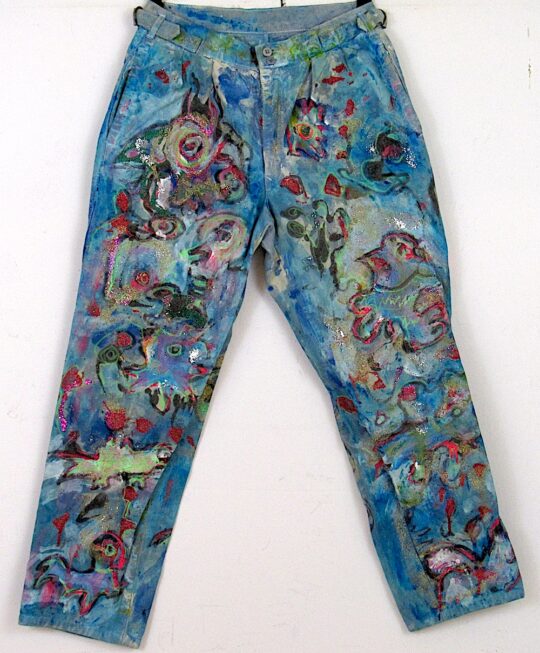

DETAILSSusie’s Jeans, 1980s

40 x 20 inches (101.6 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

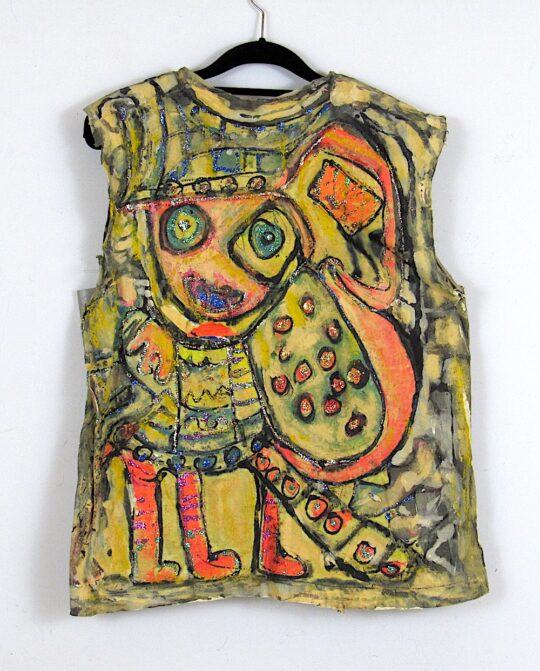

DETAILSCreature No.2 (t-shirt), 1985

41 x 40 inches (104.14 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Cellist No.4, 1980s

24 x 19 inches (60.96 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFamily Trip, 1980s

24 x 36 inches (60.96 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Orphanage, 1980s

29.5 x 22.5 inches (74.93 x 57.15 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCoaster Creature, 1980s

39 x 36 inches (99.06 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNonsensical, 1980s

43 x 34 inches (109.22 x 86.36 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSchool House Rock, 1980s

36 x 35 inches (91.44 x 88.9 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Odd Couple, 1991

26 x 40 inches (66.04 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStreamers, 1980s

46 x 27 inches (116.84 x 68.58 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAvian Committee, 1980s

48 x 54 inches (121.92 x 137.16 cm)