As is often the case, one’s first encounter with a new work of art, especially if the artist is unknown to the viewer, is both personal and emotionally complex. This being the case, feelings may shift back and forth, from exhilaration to an equivocal indecisiveness. Such responses are not unusual among those who visit New York galleries on a regular basis. Occasionally, one may experience a special moment upon discovering an artist whose work transmits some unidentifiable, overwhelming attraction. The Mexican poet and critic Octavio Paz spoke of this attraction as a subtle rendezvous where one feels an ineffable bond with an artist’s work. In such cases, a sensory connection occurs, almost beyond explanation. Apparently this happened to the art gallerist Ken Nahan when he first discovered a small painting by Rafal Olbinski in 1990, which he soon after presented to his wife, Sherri. The couple’s attraction to Olbinski’s paintings was instantaneous and soon became unstoppable. The connection has persisted for more than two decades and still continues to grow.

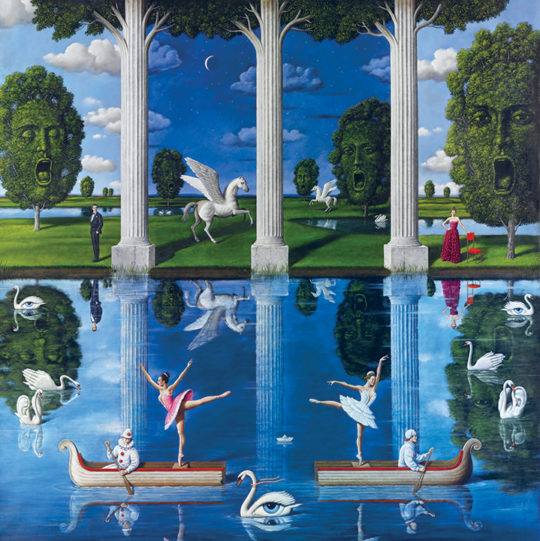

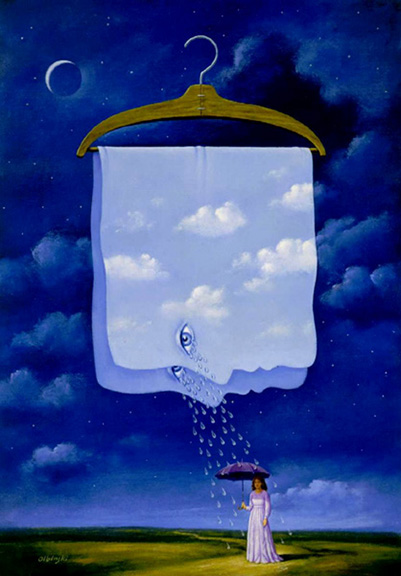

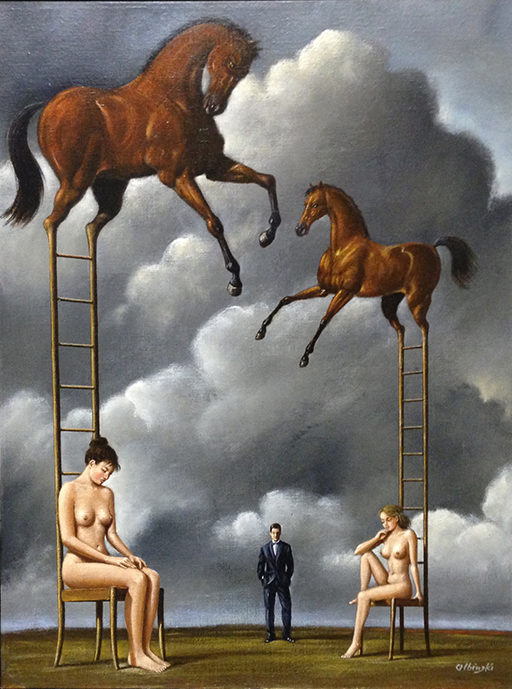

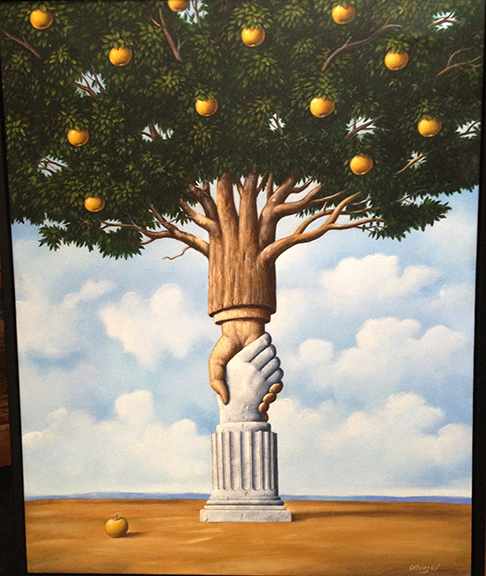

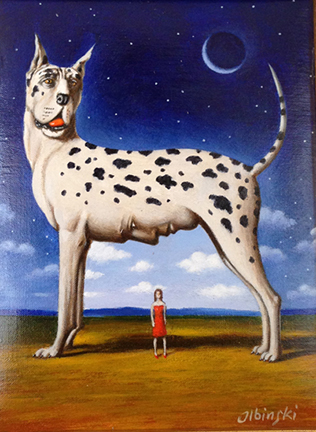

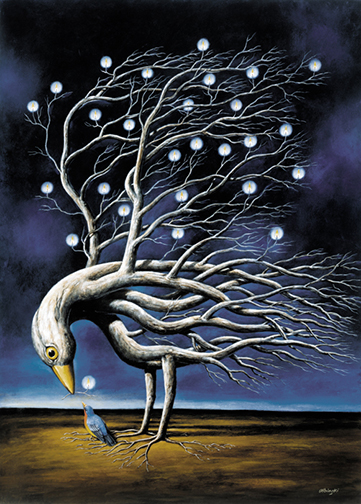

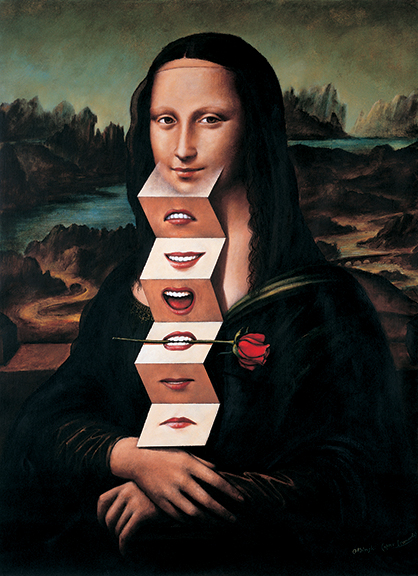

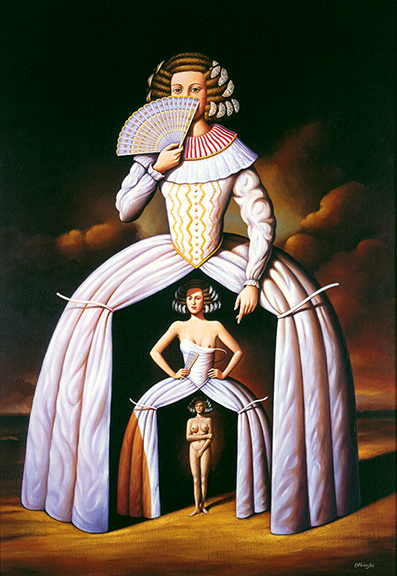

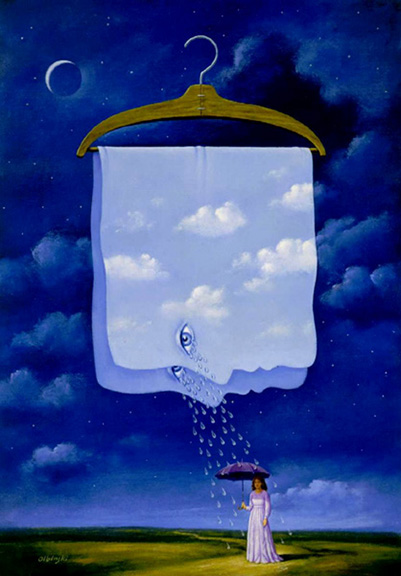

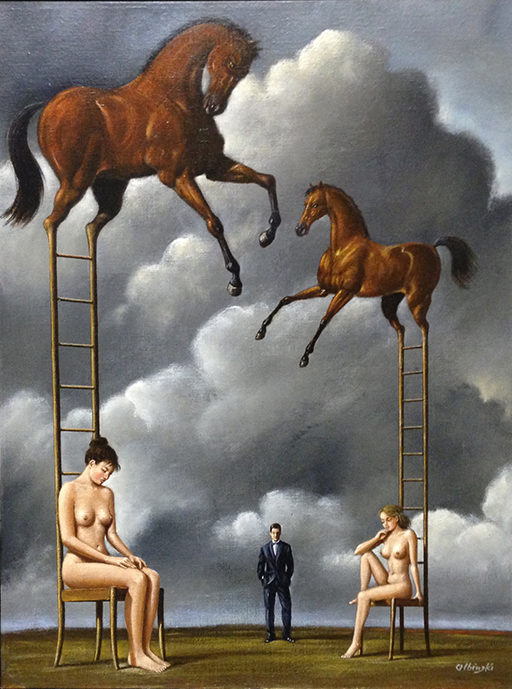

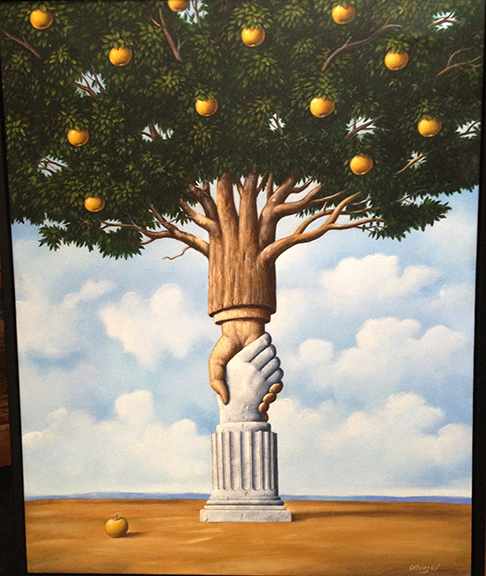

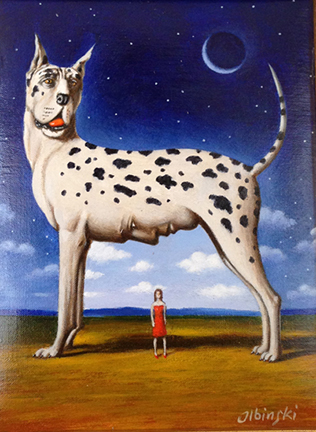

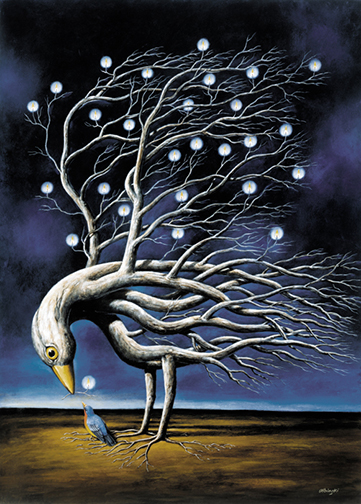

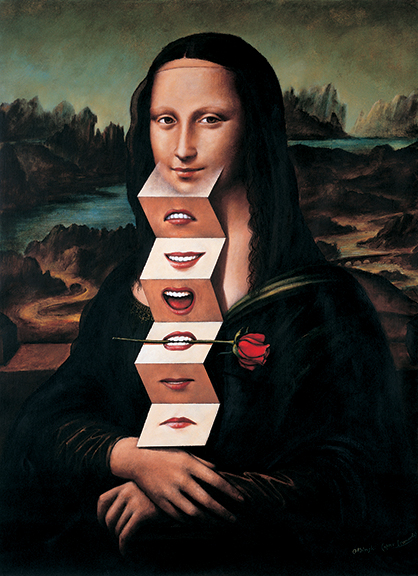

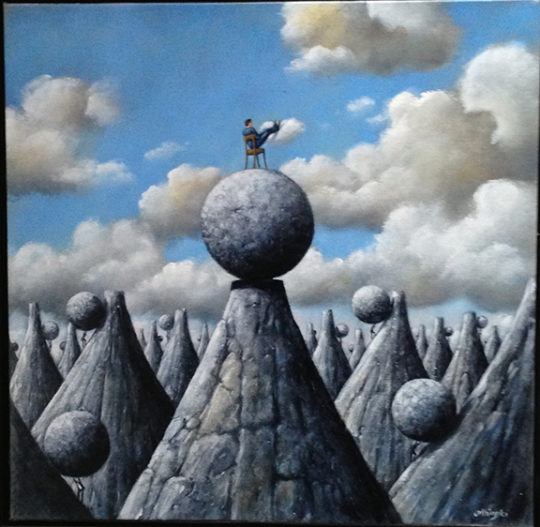

Although I had heard of Olbinski both as a designer and painter, my initial encounter with the artist occurred recently. I was invited to his studio in midtown Manhattan where he paints when he is not in Europe (where he frequently exhibits) or voyaging elsewhere to exotic beaches in the southern hemisphere. My first impression of his New York atelier was a kind of “installation art” with its narrow, darkened environs cluttered with paintings, some of which were finished, while most were clearly not. Generally modest in scale, the newly completed works sat in piles or were rolled up, waiting to be measured, stretched, and framed. Smaller paintings appeared on tables with half-filled cups and glasses, along with pairs of eyeglasses, thus signaling the artists precision and delicacy made evident in each of his works. Other paintings were placed on shelves among books and antiques, many either sent or brought from Warsaw or other parts of Eastern Europe. The dingy, lustful, overstuffed, and unmatched furniture crowded out any possibility of excess space. One must carefully negotiate a path carefully from one end of the studio to the other. Somehow these compressed, old world quarters matched perfectly with Olbinski’s brilliantly complex and paradoxical imagery, filled with mutated classical-style figures, fish, birds, buildings, statuary, costumes, and landscapes in a various stages of metamorphosis. The intensity of the artist’s demeanor was present throughout the studio. Writers and critics coming from fine arts and design have referred to his paintings as Surrealist, often comparing his approach to the Belgian artist, René Magritte (though temperamentally he may be closer to yet another Belgian painter, Paul Delvaux). These affinities may be found not only among Olbinski’s paintings but in his graphic works as well, many of which have been commissioned for various plays, ballets, and operas, including Oedipus the King, Woyzeck, The Magic Flute, Swan Lake, The Marriage of Figaro, among other elegant, haut bourgeois performances.

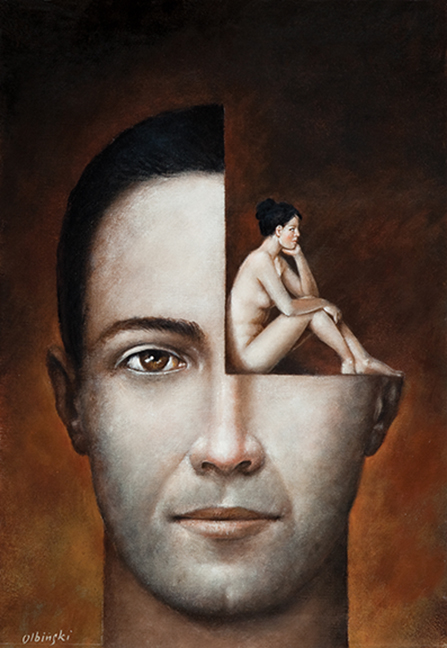

If one were to remove the language from almost any poster designed by Olbinski, such as the name of the opera or play, along with that of the composer or author, the image would still hold. This suggests that many of his graphic works could function just as well as paintings without the print. In fact, many of his paintings are simply variations of earlier graphics and visa versa. In either case, the rigor and density of Olbinski’s imagery tends to provoke ambiguity. Put another way, it offers a kind of seductive uncertainty, whereby the image points in many directions simultaneously rather than in a single direction. By allowing his figures to exist in an ambiguous space, their meaning becomes autonomous. They are suspended in time, but never facile in their appearance. This autonomy of meaning gives some of his work an aura of relative inscrutability, at least upon first glance. A good example would be the painting titled Declaration of Righteousness (2011). Here a tuxedoed man wearing a red wizard’s hat stands to the left in an empty room partially illuminated by sunlight. The room has two arched windows that face the open sea. The man is holding the corner of a painting on canvas supported at the opposite on the right by a bird with fluttering wings. The subject on the canvas is the rear view of a nude woman seen from the buttocks upwards as she emerges from the sea in the painting that shares the same horizon as the actual sea that appears outside the two arched windows. Her brunette wind-blown hair goes to the right, thereby suggesting a wind from the sea. But is the wind from inside the painting or outside the arched windows. In either case, the wind is merely a specter within either the painting of the painting or the painting itself. Her neck and head extend beyond the upper reaches of the canvas being held by the man and the bird as if to suggest she is both physically in the room as she is also a painterly illusion. As we peer to the lower right of the painting within the painting, we notice a small paper boat that seems to coexist with the clipper ship visible in the distance near the horizon outside the window. Olbinski's Declaration of Righteousness is replete with ambiguity from every angle, from every point of view. Yet in spite of its complexity, the paradoxical aspect of this work stands steady. Everything fits within the system of the painting. It is a philosopher’s painting that stretches the relationship of the imagination in terms of both reality and illusion, finally questioning the existence of both.

In short, there is no single definitive meaning given to the paintings of Olbinski. Instead, his images offer the viewer a bizarre, often elusive (and illusive), connotation that exceeds the limits of the text. Take, for example, the artist’s bravura poster for The Egyptian Helen, perhaps one of the least successful operas by Richard Strauss. Here we discover Helen as a toga donned, nude-breasted elixir, who rides not inside a wooden horse, but reclines atop the shell of an eroticized scallop. Instead of posing nude while standing upright within the fluted half-shell a la Botticelli, Helen alludes to her alter Ego — an enormous scallop with swooning red lips — suggesting the classical, yet seedy allure of Jayne Russell. Standing to the right side of our narcissistic Helen in the background near the sea, Olbinski blithely represents a miniature modern-day fashion model, posing as a nude Proteus while standing beside his eternal trident. The irony is magnificent. Helen of Troy is transformed into a semiotic ploy, an obverse allegory. What we expect from this mythic heroine suddenly reverts to the unexpected. Olbinski has transformed the heraldic Helen into an ironical pin-up, a slothful playgirl who admonishes our sense of hyper-reality. It would appear that the artist has given Strauss phantasm a cosmetic face-lift in tandem with the philosophy of Heidegger, who advocated that Greek legends should be performed not on ancient stages but in contemporary time and space where the power of the allegory becomes renewed by way of ambiguity.

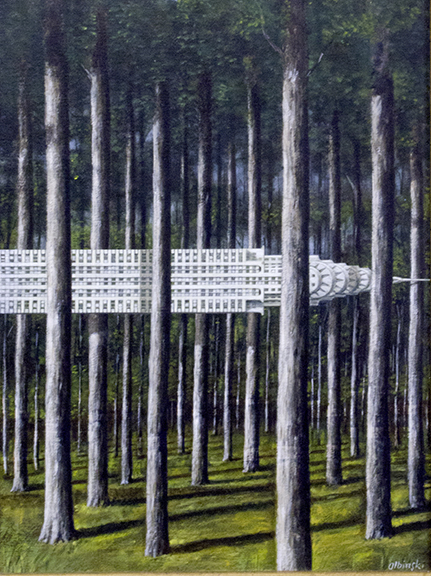

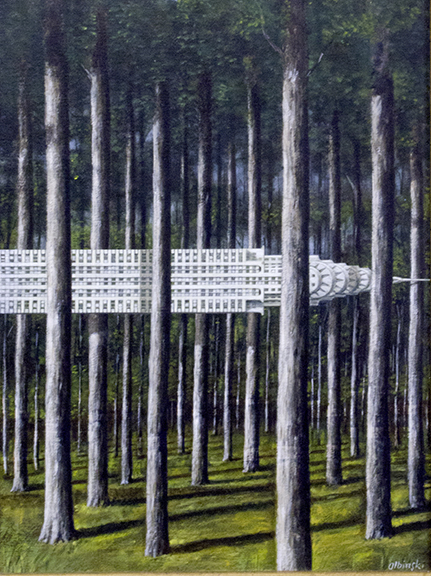

The notion of representing an opposition, such as dawn in relation to dusk, or a normally small object that suddenly appears large, within the formal structure of a painting was frequently used by Magritte. When two opposites appear united in the same painting, as they often do in a Magritte, this ambiguity constitutes a paradox. To paint an eagle soaring over a mountain is one thing. It is something else to transform the eagle into a stone mountain. This Surrealist approach to painting is borrowed repeatedly in the work of Olbinski with one major exception. No matter how convincing the fantasy may appear, it is never irrational. The signs within the painting are as rational as a game of chess. In Eternity Lost (2002), where the familiar Chrysler building in midtown Manhattan is painted horizontally on a lesser scale in the middle of a forest, the resurgence of the Freudian phallus is contingent on fantasy. Nonetheless, the formal structure of this painting is completely rational. One might argue that nothing is out of place, which is generally true in the paintings of Olbinski. The fact that nothing is out of place (in the formal sense) only further reinforces the presence of ambiguity. The opposition folds in upon itself and provokes us to think as to where we are in this painting. How do we come to terms with what we are seeing? The scenario may appear irrational from the point of view of the external visual world, but in the painting everything holds together perfectly. What we are seeing in Eternity Lost is not the external visual world but the artist's fantasy, which in terms of painting is formal and entirely rational. One might further suggest that this paradigm is also within the practice of psychoanalysis to the extent that what appears rational in the mind of the patient is paradoxically irrational in the external everyday world. But art is not psychoanalysis, and psychoanalysis in not art. One cannot neither prove nor disprove the content of a painting. This is, perhaps, why the truly great analysts of the past sought the company of works of art that reified signs of ambiguity.

In the previously discussed Helen poster, both paradox and ambiguity are present. There is no doubt. But to grasp the paradox depends largely on knowing the “literary” and historical reference taken from the Greek myth. The metaphorical irony of this juicy red-lipped scallop hidden inside its shell while the temptress (Helen) reclines on top is to predict the siege of Troy. The seduction is very real. Without the presence of the seductress, the virtue of ambiguity is disabled, impotent, and therefore unable to perform. Paradox and ambiguity are important in an Olbinski painting. To paint a purely literal interpretation of a scenario is to reduce its affect. Without seduction, there is no real paradox and no ambiguity. There is no irony that connects us to our humanity. Just as a well-constructed opera or play reveals the irony present in our everyday lives, so Olbinski’s paintings aspire to do the same. Irony is what makes us laugh and cry, and it is what gives these paintings their subtle force. Without the seduction of the temptress — even when disguised as the forest glade that invites the Chrysler Building — none of this happens.

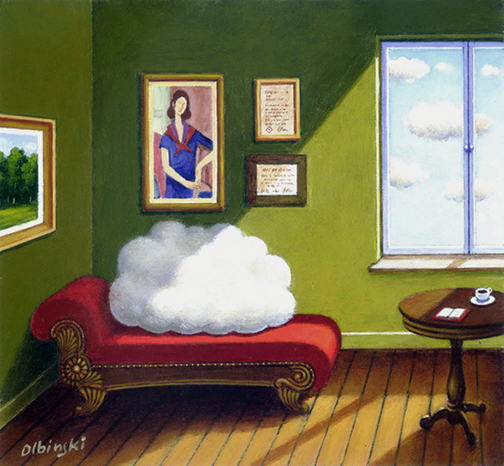

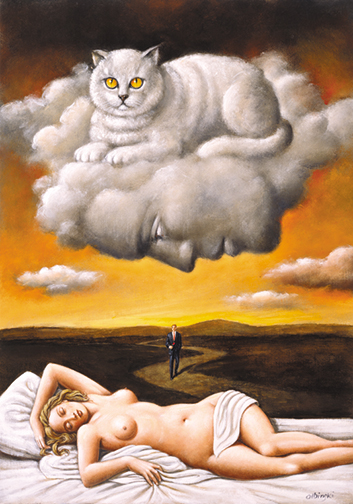

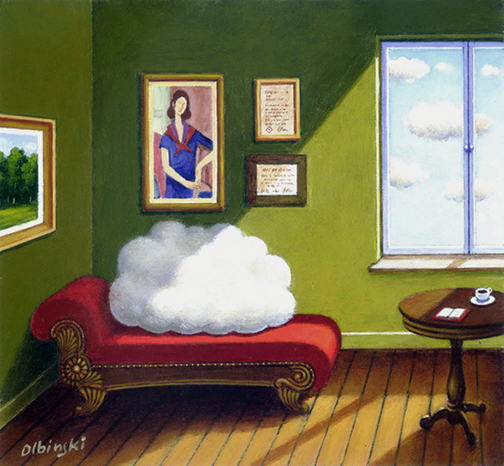

Let’s compare two Olbinski paintings in the current exhibition, Casual Temptation and Intimacy Revisited (both 2011). There is a paradox visible within each painting. While the artist may have considered external “literary” references, they do not appear essential to our reading. In Casual Temptation, the focus is clearly given to the central figure; a young woman scantily clothed in a bathing suit fondles her pearl necklace. As if to beckon our voyeuristic delight, three inverted triangles are visible on the horizon between sea and sky, one of which falls directly in line with the woman’s sex. Even so, we view the woman almost nonchalantly— concurrently — with the sailboats that glide across the sea. Her allure is phantasmagorical, yet ultimately seductive. Intimacy Revealed is typical in terms of the artist’s irony but different in approach from Casual Temptation. Here no figure is present. Rather we are looking at an empty, brightly sunlit room. Most likely, the room is the office of an analyst with certificates framed on the wall. The cumulus clouds in the sky outside of window connect with another cumulus cloud that rests inside the room on a couch designating for reclining. Above the couch is the artist's reproduction of an abstract portrait of a woman by Picasso, Le Reve (The Dream), (1932). A small cat lies on the rug in front of the couch, and an open book with a demitasse sits on a small table nearby.

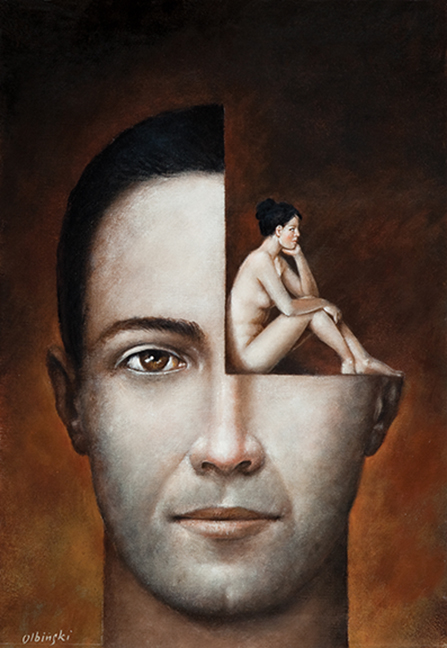

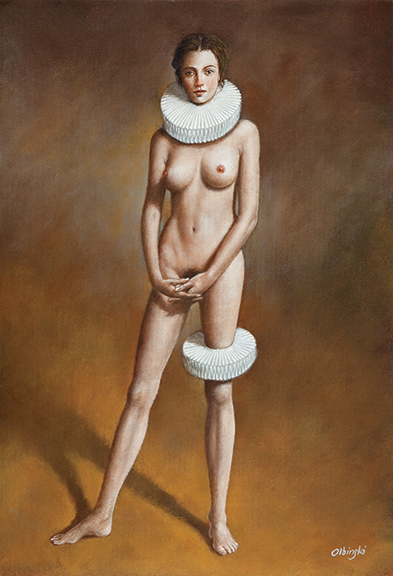

A poetic quality exists both within and between these two paintings, revealing two sides of a woman. In Casual Temptation, the seduction is more direct. In Intimacy Revealed this quality is perceived more indirectly, more erotically, in the form of a cloud that symbolically reclines on a couch. The two sides in Olbinski’s work are complementary. In each case the seductress takes a different form, as the paintings themselves test the air between men and women from a transformative, dream-like, even voyeuristic point of view. The sexual subject matter is pervasive in the work of the artist, but it is also complex, as I have tried to suggest. There is literally more than meets the eye. One senses that the eye of the artist is rarely detached from the body, which further suggests an involvement — no matter how detached or discrete — not only with the design of the figures, but with their hidden imaginative aspects, almost as if somehow his figures were removed from time and kept still within the space of a dream.

— Robert C. Morgan

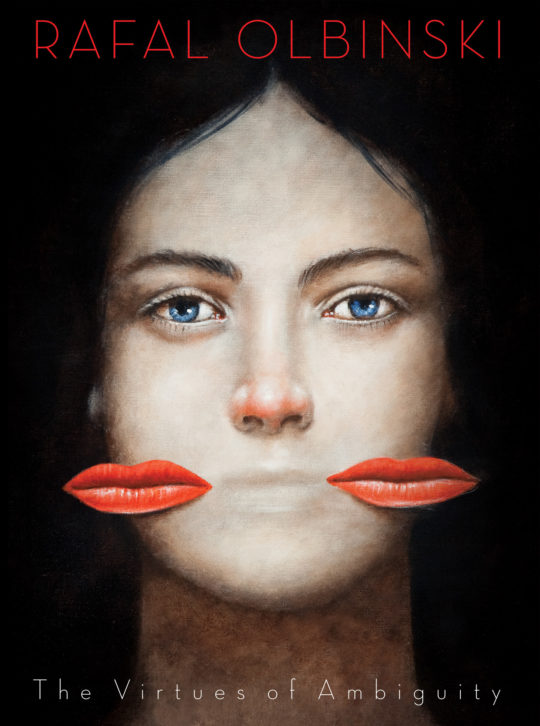

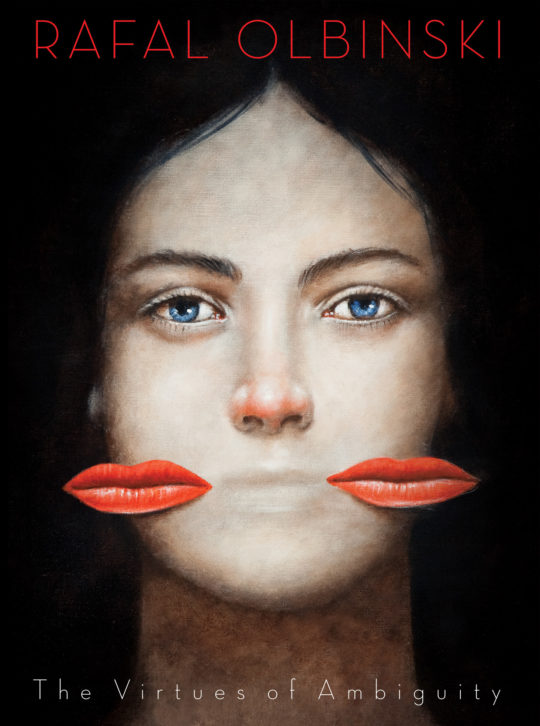

Surrealism: The Virtue of Ambiguity

-

Abundant Prophesy II, 2001

19.5 x 20.5 inches (49.53 x 52.07 cm) -

Accidental Necessity – Antigone, 2012

18 x 11 inches (45.72 x 27.94 cm) -

Apollo and Daphne, 2012

23.5 x 29 inches (59.69 x 73.66 cm) -

Casual Temptation, 2011

23.5 x 30.75 inches (59.69 x 78.11 cm) -

Coherent Episode, 2009

21.5 x 36 inches (54.61 x 91.44 cm) -

Compelling Sense of Dislocation, 2003

20 x 29 inches (50.8 x 73.66 cm) -

Confession of a Compulsive Dreamer, 2007

27 x 35.5 inches (68.58 x 90.17 cm) -

Contemplative Insight, 2013

29 x 22 inches (73.66 x 55.88 cm) -

Conventional Destiny, 2011

5.5 x 7 inches (13.97 x 17.78 cm) -

Conventional Sentiment, 2012

22.75 x 26.75 inches (57.79 x 67.95 cm) -

Convincing Impossibility, 2012

18 x 11.5 inches (45.72 x 29.21 cm) -

Customary Sentiment, 2013

16 x 24 inches (40.64 x 60.96 cm) -

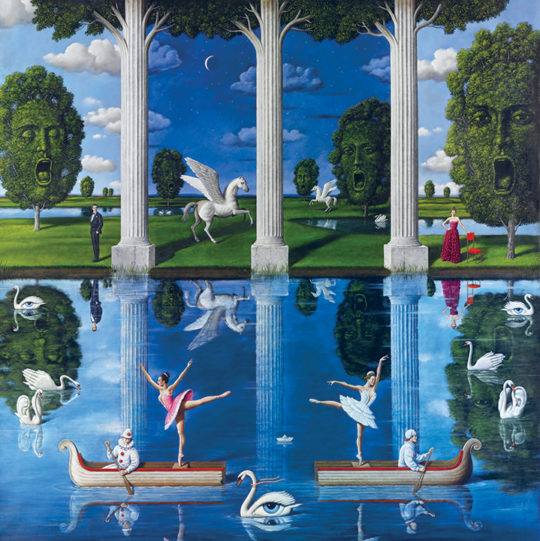

Customary Transition (diptych study for Warswaw Opera curtain), 2011

79 x 79 inches (200.66 x 200.66 cm) -

Declaration of Righteousness, 2010

23.5 x 16 inches (59.69 x 40.64 cm) -

Diverse Imaginations, 2011

7 x 7 inches (17.78 x 17.78 cm) -

Duality of Expression, 2013

13.75 x 18 inches (34.93 x 45.72 cm) -

Eternity Lost, 2002

1419.5 x 18 inches (3 x 45.72 cm) -

Festival of Pleasant and Unpleasant Plays, 2003

32 x 23 inches (81.28 x 58.42 cm) -

Grand Master of Lesser Ceremony, 1996

21.75 x 31.75 inches (55.25 x 80.65 cm) -

Habitual Condition of Aesthetic Intercourse, 2008

16 x 10 inches (40.64 x 25.4 cm) -

Impersonal Product of Time, 2003

17 x 23 inches (43.18 x 58.42 cm) -

Informal Unity, 2008

27.75 x 34 inches (70.49 x 86.36 cm) -

Interpretation of Habits, 2008

20.75 x 27.5 inches (52.71 x 69.85 cm) -

Intimacy Revisited, 2011

40 x 40 inches (101.6 x 101.6 cm) -

Intimidating Quality, 2012

5.25 x 7 inches (13.34 x 17.78 cm) -

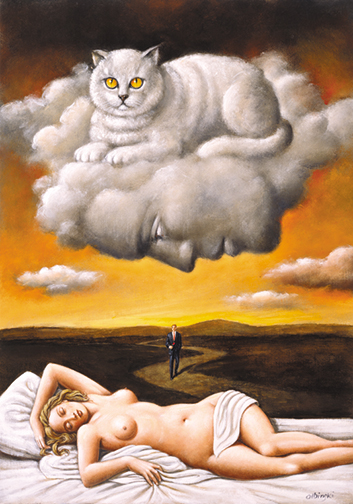

Le Chat Blanc, 2012

6 x 8.5 inches (15.24 x 21.59 cm) -

Maria Stuarda, 2013

21.25 x 12.5 inches (53.98 x 31.75 cm) -

Melancholy of Virtuous Instinct, 2012

13.5 x 19.5 inches (34.29 x 49.53 cm) -

Mythology of Noble Restraints, 2012

5 x 7 inches (12.7 x 17.78 cm) -

Nocturnal Fascinations, 2013

14.25 x 20.25 inches (36.2 x 51.44 cm) -

Prohibitive Diversion, 2009

9 x 13.5 inches (22.86 x 34.29 cm) -

Revenge of the Interpretation, 2013

17.75 x 30 inches (45.09 x 76.2 cm) -

Sentimental Attentiveness, 2009

22 x 11.5 inches (55.88 x 29.21 cm) -

Sentimental Effusion, 2011

6.5 x 7 inches (16.51 x 17.78 cm) -

Study for Consolation of Skepticism, 2012

12 x 9 inches (30.48 x 22.86 cm) -

Study for Superiority of Consequences, 2007

18 x 18 inches (45.72 x 45.72 cm) -

Substitution for Appearance, 2013

11.5 x 16.5 inches (29.21 x 41.91 cm) -

Subtle Precondition of Passion, 2008

19.75 x 29.5 inches (50.17 x 74.93 cm) -

Superficial Understanding of Appearances, 2012

35.5 x 35.5 inches (90.17 x 90.17 cm) -

The Length of the Dream, 2002

13.75 x 17.5 inches (34.93 x 44.45 cm) -

The Virtue of Amiguity, 2013

20 x 29 inches (50.8 x 73.66 cm) -

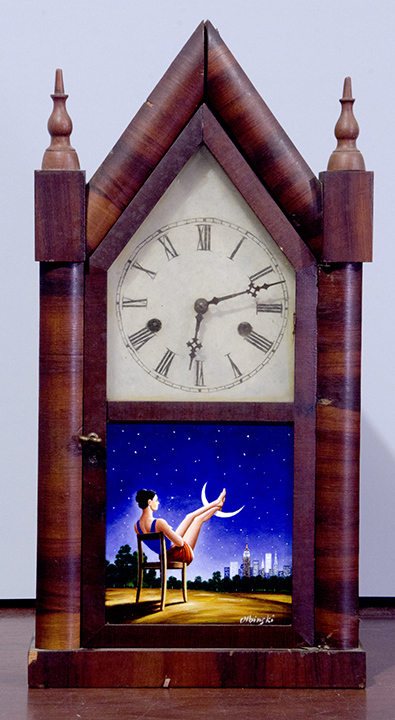

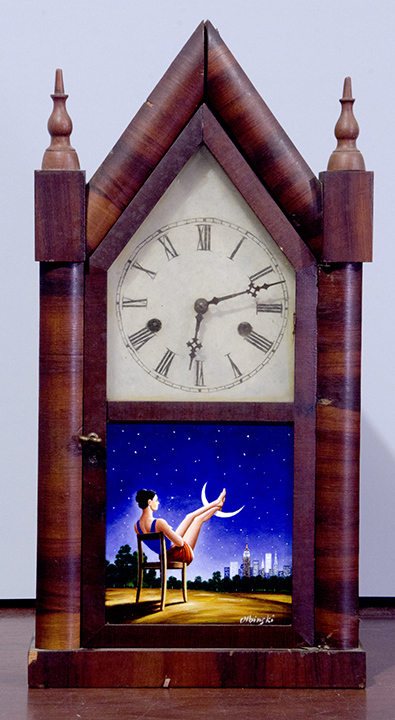

Third Dimension of Time (antique clock), 2010

9 x 19.5 inches (22.86 x 49.53 cm) -

Universality of Contradiction, 2008

21 x 32 inches (53.34 x 81.28 cm)

-

Abundant Prophesy II, 2001

19.5 x 20.5 inches (49.53 x 52.07 cm) -

Accidental Necessity – Antigone, 2012

18 x 11 inches (45.72 x 27.94 cm) -

Apollo and Daphne, 2012

23.5 x 29 inches (59.69 x 73.66 cm) -

Casual Temptation, 2011

23.5 x 30.75 inches (59.69 x 78.11 cm) -

Coherent Episode, 2009

21.5 x 36 inches (54.61 x 91.44 cm) -

Compelling Sense of Dislocation, 2003

20 x 29 inches (50.8 x 73.66 cm) -

Complexity of Movement, 2013

14 x 19.75 inches (35.56 x 50.17 cm) -

Confession of a Compulsive Dreamer, 2007

27 x 35.5 inches (68.58 x 90.17 cm) -

Contemplative Insight, 2013

29 x 22 inches (73.66 x 55.88 cm) -

Conventional Destiny, 2011

5.5 x 7 inches (13.97 x 17.78 cm) -

Conventional Sentiment, 2012

22.75 x 26.75 inches (57.79 x 67.95 cm) -

Convincing Impossibility, 2012

18 x 11.5 inches (45.72 x 29.21 cm) -

Customary Sentiment, 2013

16 x 24 inches (40.64 x 60.96 cm) -

Customary Transition (diptych study for Warswaw Opera curtain), 2011

79 x 79 inches (200.66 x 200.66 cm) -

Declaration of Righteousness, 2010

23.5 x 16 inches (59.69 x 40.64 cm) -

Diverse Imaginations, 2011

7 x 7 inches (17.78 x 17.78 cm) -

Duality of Expression, 2013

13.75 x 18 inches (34.93 x 45.72 cm) -

Eternity Lost, 2002

1419.5 x 18 inches (3 x 45.72 cm) -

Festival of Pleasant and Unpleasant Plays, 2003

32 x 23 inches (81.28 x 58.42 cm) -

Grand Master of Lesser Ceremony, 1996

21.75 x 31.75 inches (55.25 x 80.65 cm) -

Habitual Condition of Aesthetic Intercourse, 2008

16 x 10 inches (40.64 x 25.4 cm) -

Impersonal Product of Time, 2003

17 x 23 inches (43.18 x 58.42 cm) -

Informal Unity, 2008

27.75 x 34 inches (70.49 x 86.36 cm) -

Interpretation of Habits, 2008

20.75 x 27.5 inches (52.71 x 69.85 cm) -

Intimacy Revisited, 2011

40 x 40 inches (101.6 x 101.6 cm) -

Intimidating Quality, 2012

5.25 x 7 inches (13.34 x 17.78 cm) -

Le Chat Blanc, 2012

6 x 8.5 inches (15.24 x 21.59 cm) -

Maria Stuarda, 2013

21.25 x 12.5 inches (53.98 x 31.75 cm) -

Melancholy of Virtuous Instinct, 2012

13.5 x 19.5 inches (34.29 x 49.53 cm) -

Mythology of Noble Restraints, 2012

5 x 7 inches (12.7 x 17.78 cm) -

Nocturnal Fascinations, 2013

14.25 x 20.25 inches (36.2 x 51.44 cm) -

Prohibitive Diversion, 2009

9 x 13.5 inches (22.86 x 34.29 cm) -

Prospective Ideas, 2013

7.5 x 10.5 inches (19.05 x 26.67 cm) -

Revenge of the Interpretation, 2013

17.75 x 30 inches (45.09 x 76.2 cm) -

Sentimental Attentiveness, 2009

22 x 11.5 inches (55.88 x 29.21 cm) -

Sentimental Effusion, 2011

6.5 x 7 inches (16.51 x 17.78 cm) -

Study for Consolation of Skepticism, 2012

12 x 9 inches (30.48 x 22.86 cm) -

Study for Superiority of Consequences, 2007

18 x 18 inches (45.72 x 45.72 cm) -

Substitution for Appearance, 2013

11.5 x 16.5 inches (29.21 x 41.91 cm) -

Subtle Precondition of Passion, 2008

19.75 x 29.5 inches (50.17 x 74.93 cm) -

Superficial Understanding of Appearances, 2012

35.5 x 35.5 inches (90.17 x 90.17 cm) -

The Length of the Dream, 2002

13.75 x 17.5 inches (34.93 x 44.45 cm) -

The Virtue of Amiguity, 2013

20 x 29 inches (50.8 x 73.66 cm) -

Third Dimension of Time (antique clock), 2010

9 x 19.5 inches (22.86 x 49.53 cm) -

Universality of Contradiction, 2008

21 x 32 inches (53.34 x 81.28 cm)

When one thinks about surrealism, what might immediately come to mind is André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, calling for the rebellion against the accepted conventions in art, and instead going in the direction of dreams, hallucinations, subconscious, and myth. In the ordinary sense “surreal” refers to the absurd, the unreal, the fantastic, the bizarre. It just so happens that all of these terms could be used to describe the reality of everyday life for an artist growing up in Communist Poland. One of the elements of that reality was a constant game with censorship, requiring skillful handling of the metaphor.

Rafal Olbinski was born on February 21, 1943 in Kielce, a small town where the gray reality of post-war life was colored with youthful dreams. His high school teachers introduced him to classical poetry as well as Greek and Roman mythology. After graduating from high school he enrolled at the Department of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology. During this period of political repression Polish posters had great popular appeal because they played the game of metaphors while implementing surrealistic humor. While still in school, Olbinski began to design his first posters and decided that creating art, not architecture, would be the source of his livelihood.

In 1970, Olbinski began working as art director for Jazz Forum, the iconic international jazz magazine founded in Poland in 1965. For the next decade he was the magazine’s primary artist, creating cover illustrations and layouts that were graphically unique. In Communist Poland, jazz was synonymous with freedom and Jazz Forum was a window to the world. It was during this period when he developed his unique visual language of symbolism in a precise and painterly style, touched by a piquant wit and the element of surprise. His also became known for his practice of freehand lettering in his posters, which is an integral part of the composition. His work at Jazz Forum opened many doors, leading to his design of several Polish record labels and album covers. He also created posters for jazz festivals such as Warsaw’s famous “Jazz Jamboree” and its “Golden Washboard” and to the south, in Lublin, the “Jazz Vocalists’ Meeting.” Olbinski’s jazz posters in Poland have never been surpassed. During this decade he also joined a group of artists creating circus posters, often using humorous or ironic metaphors to depict a subject. Most of his illustrations were executed in a realistic style with a static composition, limited to a palette predominantly in warm browns.

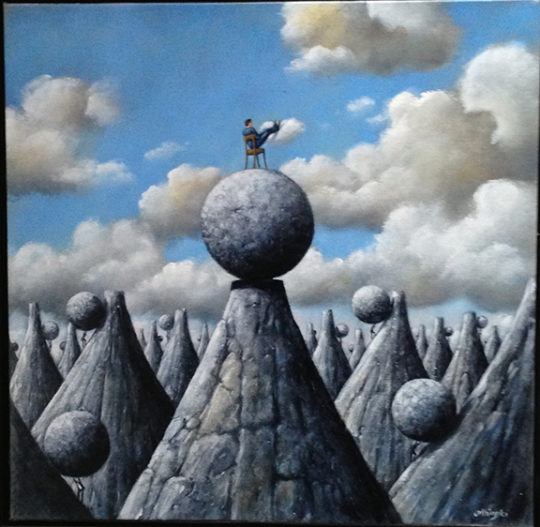

Olbinski continued to develop his own catalog of intriguing metaphorical imagery, always presenting visual puzzles for the viewer. At the same time, his approach is tempered by a quest for classic harmony and beauty. Both his settings and his characters are grounded in realism but they oscillate around unexpectedly playful and surreal associations. Viewers are drawn in by what appears to be a conventional approach only to discover that the elements of his imagery are far more complex.

While independent of movements and schools Olbinski has certainly drawn upon the achievements of his predecessors in surrealism. His approach developed within the rich tradition of the Polish School of Posters, which since the early 1950s has exerted a significant influence upon international graphic design. That movement is celebrated for its painterly vivacity, expressive line, the use of collage, surreal language, allusions, humor, handwritten typography, and a lyrical and romantic character. During the reign of Communism there was far less need for commercial advertising. Posters provided practical information but they were also artistic in nature because they were created by the best Polish artists in favor with the State. Paradoxically, these artists disguised the political criticisms they frequently inserted in their posters.

Olbinski was quickly categorized as a surrealist but he says it was not his intention: “I guess I’m an inborn surrealist. Back then I was completely uninterested in René Magritte, Paul Delvaux, Marcel Duchamp, or Max Ernst. Everything I did stemmed from the observation of our reality, which was extremely surreal.”1 Nevertheless the distinct impact of Magritte’s surrealistic imagery would become increasingly evident in Olbinski’s paintings — especially after his trip to New York in the fall of 1981, when he was asked to appear at the opening reception for an exhibition of his posters at The Polish Institute of Arts & Sciences of America (PIASA). Suddenly, on December 13, 1981, martial law was declared in Poland. Once again Olbinski found himself in a surreal reality: this time the borders of his native land were closed to him. He was surprised to have found himself “trapped” in America, the land of freedom, the promised land for many immigrants. During that first poster exhibition he met Carveth Cramer, the artistic director of Psychology Today. In March of 1982, that magazine published Olbinski’s first cover in America. This accomplishment was followed by covers for Time, Newsweek, Business Week, Playboy and many other magazines. Despite having to adjust to the requirements of editorial policy, his distinctive hand-painted covers stood out in a market that would soon be dominated by computer graphics. In a remarkably short time Olbinski was established as a prominent illustrator.

The 1980s was also a time when the editors of The New York Times, were looking for a new approach to illustration for the paper’s op-ed section. They were impressed by the surrealist style of émigré artists from Eastern Europe who, after experiencing years of censorship had developed a unique visual language marked by an outstanding ability to express concepts with metaphor and a sarcastic sense of humor. Along with Olbinski, Polish artists such as Andrzej Dudzinski and Janusz Kapusta surprised editors with their unusual ideas and technical excellence — and became very visible in the op-ed pages. Jerelle Kraus, then the art director of The New York Times, considered Olbinski a virtuoso of a surrealism.2 The black and white nature of the press illustration did not diminish his work; on the contrary, it added a new dimension, enhancing the artist’s formal solutions. By employing the elements of landscape to lend a sense of space and depth, and by referencing Magritte, Olbinski enhanced his repertoire in illustration. And, rather than giving up its application to the poster, he gradually made it the most wide-reaching ambassador for his work.

In the early 1990s the New York City Opera was looking for someone who would continue its poster style as created by Richard C. Hess [1934-1991], also influenced by Magritte. Olbinski became the natural successor and went on to create a famous series of posters in which he constantly surprised the viewer not only with his technical virtuosity, but with original iconography, creativity, and his unique sense of surrealism to convey the narrative libretto. His opera posters are distinguished by their mastery in transferring the emotion and dynamics of opera. Often, he travels back in art history and quotes parts of famous paintings. Examples include Carmen, naked and dressed (the latter version forced by the The New York Times censor), which is analogous to the two versions of Goya’s Maya; and, The Visit of the Old Lady, which recalls a coffin from Magritte; and, Gloriana, based on a drawing by Zuccari. When Olbinski draws from the figurative surrealism of Magritte, he is most often attracted to the conceptual juxtaposition of elements and metaphor to create surprise. His New York City Opera posters brought him such great popularity that to this day he continues working for many opera theaters in the United States and Europe, charming viewers with his surrealism not only in posters but in stage sets.

It was also during the 1990s when Olbinski brought his technical prowess to perfection. His vivid imagination, artistic vocabulary, and technical skills had matured together. His earlier monochromatic palette had become cleansed — it had become more intense, especially with the reds and blues. And the simplified modeling of the 1970s had given way to soft modulations in tone that reinforced the sense of form. Ever the painter, he always leaves a clear brush trail to remind the viewer of the reality of the canvas ground.

In the United States, the art market has often viewed the commercial purpose of commissioned illustration as antithetical to the fine art sold in galleries. American illustrators who earn a living through their commissions sometimes exhibit their private works under a different name, effectively leading double lives. But in European countries such as Poland poster artists and illustrators enjoy broad popular recognition. This observation has been repeated by many emigré artists. For Olbinski, however, his opera posters served as a bridge between illustration and the gallery world. He debuted as a painter in 1990 at André Zarre Gallery in New York, and to his own surprise his first show was sold out and drew the favorable attention of art critics. In 1994 he began a long relationship with Nahan Galleries in New York, captivating their audiences with each new show and increasing demand for his work. The beginning of the twenty-first century has continued with exhibitions in numerous galleries, museums, and cultural institutions around the world.

Olbinski’s visual language combines specific motifs in a variety of configurations: a tree, a vast meadow, a blue sky dotted with white clouds, a long stretch of road, birds, a curtain, a starry night sky, the coast, or a sailboat. These familiar elements reach all of us. Who hasn’t once experienced the depth of a forest, admired a quiet stream, or been captivated by the beauty and sound of crashing waves? Their memories instill in us a sense of security, a kind of a comfort zone. When one thinks about a vacation destination or even paradise these are the elements that come to mind. This is how Olbinski immediately gains the trust of the viewer who is willing to enter into his world of imagination. Sometimes that bucolic landscape is discovered to be a scene of betrayal, loneliness, and longing — perhaps related to issues of exile and leaving loved ones behind. However, owing to the beauty of these familiar surroundings these difficult concepts do not leave the viewer with a sense of anxiety, but rather a momentary reflection. Olbinski’s need to tell stories may be an attribute of illustration but his uniquely expressive style consistently infuses them with an allure and intrigue.

Olbinski points not only to Magritte as inspiration but to many artists, including Waldemar ?wierzy, Milton Glaser, Paul Davis, Bruno Schulz, and Francisco Goya. Certainly, the key to a full understanding of his work is Magritte’s poetry found in some of Olbinski’s earliest works created in Poland. His imagery matures in the illustrations for the The New York Times, the magazine covers, and the opera posters. Ultimately, each is in dialogue with Magritte while telling a completely different story — a story told in a visually provocative manner, be it one where humor and lightness prevails or the dark mystery of his Belgian surrealist predecessor comes forward. Clues are also found through the paintings’ titles. For Magritte titles served to define the objects represented, whereas for Olbinski titles are narrative introductions to the story itself.

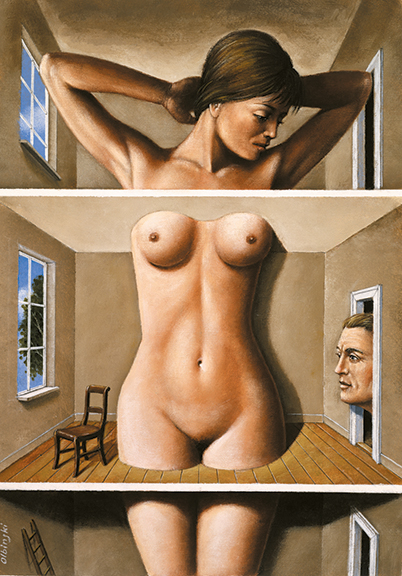

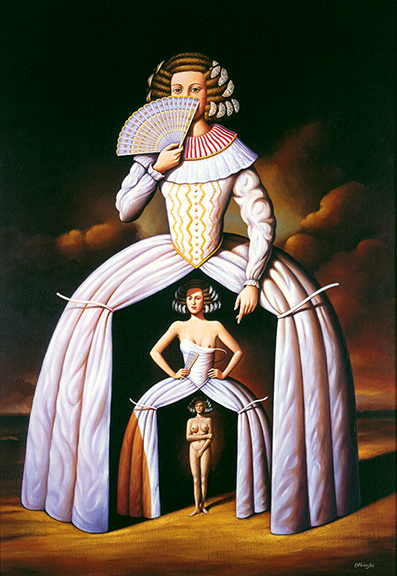

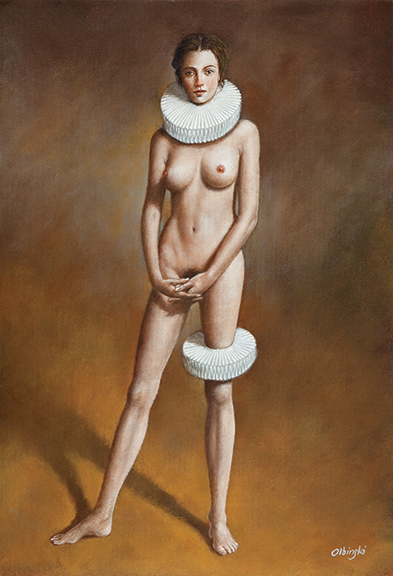

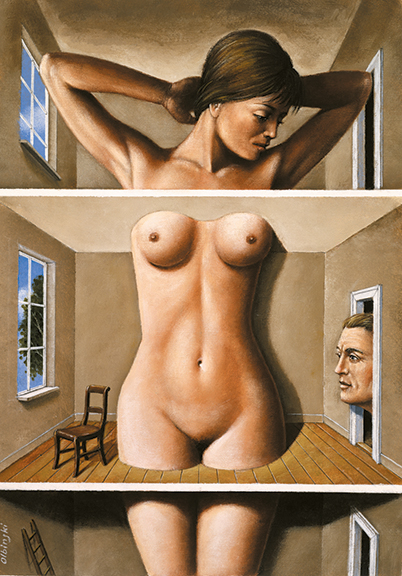

One subject of Olbinski’s paintings that is largely separate from his illustrations is the female nude. Free from any art director’s impositions of censorship, Olbinski found complete artistic freedom in his depictions of women and their idealized everlasting youth. Initially, he often depicted a woman dressed in a long, airy dress, often with her back turned to the viewer. Gradually, he presented her in increasingly bold acts, while letting her dress become an integral part of the landscape or an interior.

Olbinski refers to the influence of the Polish painter Bruno Schulz [1892-1942] — especially The Booke of Idolatry, and the way in which Schulz portrayed women.3 Like Schulz, the woman in an Olbinski painting is the central figure of the composition, unsurpassed, mysterious, and of pristine beauty. Any male presence is typically relegated to a secondary role. Both the literary and visual imagery of Schulz inspired Olbinski to paint poetic realities. In Magritte’s paintings, too, the female figure is often only a part of the picture whereas for Olbinski she is positioned as the central character around which the story is built. In this way the artist creates an atmosphere of greater intimacy as he introduces the viewer to the world of his erotic fairy tale.

Olbinski’s remarkable continuity of imagery — from illustrations, to posters, to paintings — is owing to their central role as “vessels of communication” regardless of their ultimate purpose. While other contemporary surrealists, especially those associated with neo-surrealism, often oscillate in the direction of a fantasy that employs photo-realism and digital manipulation, Olbinski has broken new ground in oil painting picked up where Magritte left off. His lyrical paintings depict emotions absent from the work of his contemporaries. Every time we see his paintings he takes us on a poetic journey. This explains why, thirty years after leaving his native country, Olbinski has remained one of the pillars among Polish émigré artists while at the same time being claimed by America as one of its greatest surrealists.

Olbinki’s symbolic artistic partnership with Magritte has earned him the title of Prince of Surrealism. In 1995 Polish photographer Ryszard Horowitz created a beautiful homage in a portrait that combines these two masters of Surrealism. It employs a visual quote from Magritte’s Castle in the Pyrenees, replacing a maritime landscape with a typically empty Olbinski clearing. The sky is covered with clouds and the rock from Magritte’s painting takes on Olbinski’s facial profile, at the top breaking into pieces, and from which a beautiful white dove escapes into the sky. As with Olbinski’s art, the dove spreads its wings to fly into worlds yet to be discovered.

— Izabela Gabrielson

1 Krystyna Gucewicz, “Zycie towarzyskie i jazzowe” Jazz Forum, April-May,1997, p. 38.

2 Jerelle Kraus, All the Art That's Fit to Print (And Some That Wasn’t): Inside The New York Times Op-Ed Page (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009, p. 151)

3 Rafal Olbinski: Women, Motifs and Variations (New York: Hudson Hill Press, 2005, p. 151)

No Events Found.