The Hidden Genius of Norman Gulamerian

Introduction

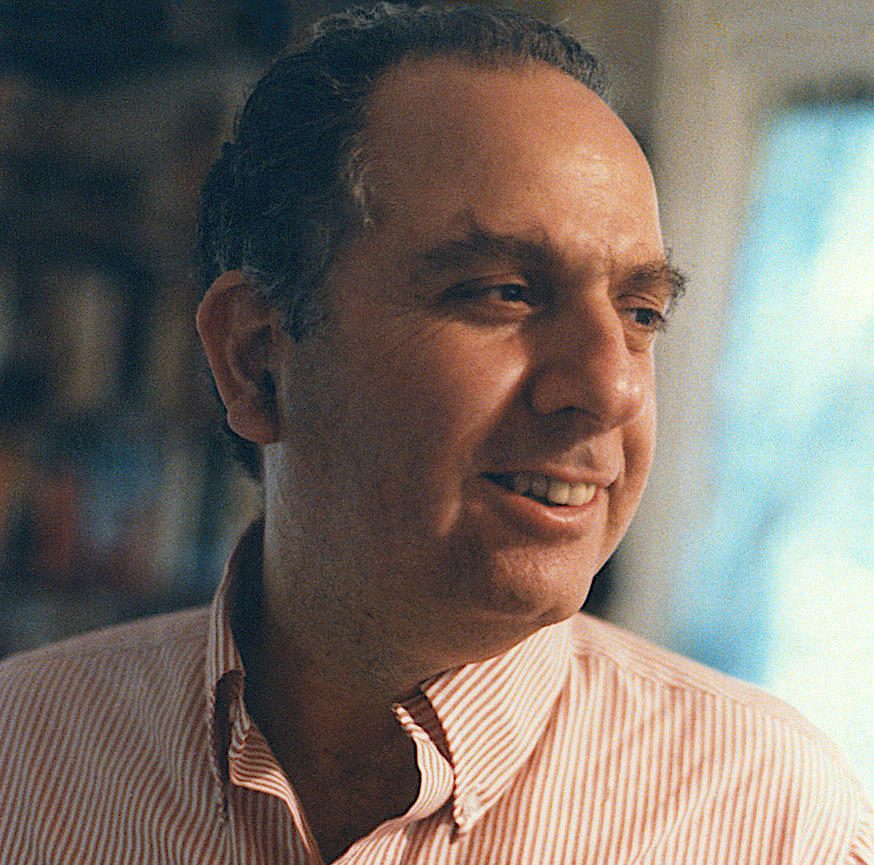

Norman Gulamerian made ground-breaking innovations in several different art-related pursuits — a combination unmatched in American art history. His body of heretofore unseen paintings assert that he was one of the most innovative masters of Figurative Expressionism during the last half of the 20th century. He was also exceptional because his commitment to developing a unique approach to painting ran parallel with equally deep engagements in directly related fields. Another of his life-long challenges was to unravel the psychological secrets of creativity — and he wrote two books on the psychology of visual perception. Another arose from his expertise in pigments, varnishes, and other artist materials. He even dropped out of art school to launch and grow what became the country’s largest and most successful art supply company, manufacturing his own brands. Along the way, he assembled a massive library of art books. Such immersions consumed so much of his time that the idea of pursuing exhibitions was precluded. Examining the striking contributions of this extraordinary creator must take into consideration all these interlocking and mutually reinforcing parts. Yet he was resolutely private while in constant pursuit of each of his dreams. As a result, few who entered the Gulamerian home home were invited into his vast studio. It was only in 2020, after he passed away at age ninety-two, that his daughters had the opportunity to delve more deeply into his archive and studio and fully grasp the enormity of his accomplishments spanning seven decades.

The nurturing of childhood genius

During 1915, German Zeppelins were bombing England while its army was releasing poison gas in Belgium to kill thousands of troops within minutes. At the same time, those horrors of World War I in Europe were providing cover for other atrocities 1,500 miles to the southeast — the methodically launched Armenian genocide, which claimed more than one million lives. Decades of persecution by Turkish Muslims resulted in an Armenian diaspora, including the more than 100,000 Armenian Christians who fled to America. Norman Berj Gulamerian, the youngest child of two of these survivors, was born in Brooklyn on August 29, 1927. His father, Marderos, was a resistance fighter in Armenia, who settled in Brooklyn and became a bookbinder. His mother, Arax Hovivian, belonged to the Armenian minority in Constantinople (now Istanbul) and narrowly escaped the massacres when hundreds were hung in the city streets. She spoke four languages and served as a translator. Starting when Norman was five years old, she regularly brought him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He would later describe a vivid recollection from one of those trips, when he was transfixed by El Greco’s only major landscape — View of Toledo — a theatrical presentation of the city perched in rugged hills with a dramatic sky looming up from the horizon. Gripping his mother’s hand, he kept looking back at the painting, even as she led him away. He was also entranced by The Vision of Saint John, filled with emotionally energetic figures. Picasso certainly would have been sympathetic with the boy because the same canvas inspired him to paint his iconic Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

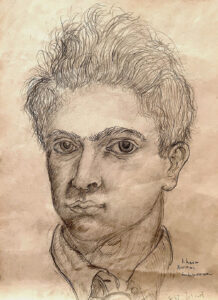

The boy deeply yearned to understand why he continued to feel such strong aesthetic reactions to certain paintings. In 1937, he revealed that he was intelligent beyond his years when bought a copy of The Aesthetic Attitude, by Herbert Sidney Langfeld. He proudly inscribed, “This book belongs to Norman B. Gulamerian.” He also inscribed the purchase date. He was only ten. Langfeld’s treatise, which combines art philosophy with psychology, was considered revolutionary when it was published in 1920. It is now regarded as influential in the rise of modern aesthetics. Gulamerian returned to the book often, writing notes in the margin indicating his grasp of Langfeld’s concepts. In particular, he noted that perception of any artwork is defined as the moment when the mind becomes conscious — has a clear impression — of the relationship between its parts. The most effective arrangement of those parts unifies our perception and can lead to passion. His astute parents soon enrolled their precocious son in classes at the Brooklyn Museum. When he was twelve, he bought his first book on Rembrandt — and soon after his parents enrolled him at the Pratt Institute to learn anatomy. His voracious appetite for art books would later yield a library of more than 8,000 volumes on artists from the Renaissance to Contemporary and covering every period, style, and movement. For perspective, that’s more art books than can be found in the collections of most public and college libraries, and it rivals that of the New York Public Library.

Coming of Age

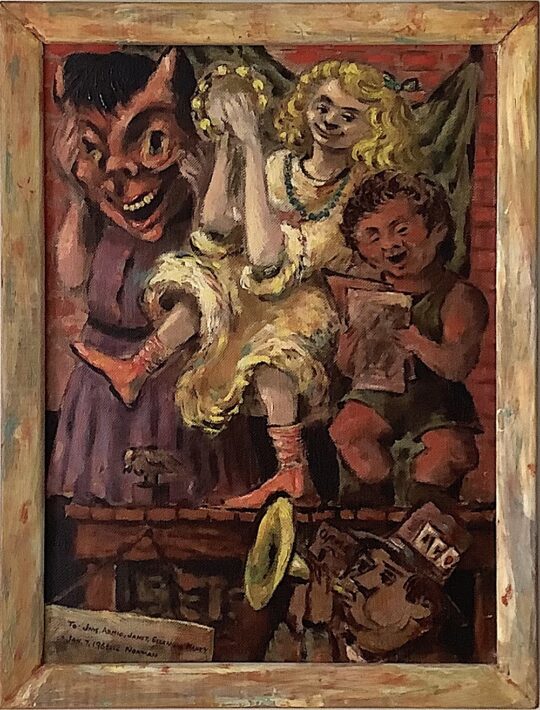

In 1942, fifteen-year-old Gulamerian was accepted to The High School of Music & Art in New York City (now the LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts). Among his artist classmates were Burt Silverman [b.1928] and Wolf Kahn [1927–2020]. Soon, Gulamerian met Frederick Taubes [1900–1981], widely known as scientist of artist materials. Taubes had just developed his eponymous brand of pigments, including his revival of a varnish used by the Flemish masters of the 14th and 15th centuries. He found in Gulamerian an apprentice skilled at grinding pigments and preparing canvases. During this stint, the teenager found confirmation in Taubes’ similarly great interest in the Old Masters of the Renaissance, Flemish, and Baroque periods. At seventeen, his canvas of an apocalyptic Biblical scene won an award from Collier’s magazine’s nationwide Scholastic Competition. In an interview with his high school’s Music & Art magazine, he said, “Art cannot exist only as sensitivity or science but that both are compounded in good proportion.” The interviewer added, “He steps easily from the physical sciences to psychology. He is immersed in writing a book on this subject now….While he lives on a highly intellectual plane somewhere in the borough of Brooklyn, he wishes it to appear that he is just another common man.” 1

In retrospect, Taubes’ inventiveness would prove to have been an inspirational seed for Gulamerian’s own business as the country’s dominant art materials manufacturer and supplier. But that seed’s germination would have to wait until World War II had ended. In 1945, not yet eighteen, Gulamerian felt compelled to quit high school and enlist in the U.S. Navy. So did his friend Wolf Kahn. In July, Gulamerian arrived in San Francisco where his ship, the 280-foot USS Monadnock, had just been converted to a mine tender. During the ship’s conversion, the war was abruptly ended in early August by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The USS Monadnock and its convoy transported Occupation troops to Japan, first unloading in Guam and Okinawa. Gulamerian celebrated his 18th birthday aboard ship before landing at the Naval base in Sasebo, Japan. When he disembarked, he saw that at least half of Sasebo had been incinerated by the atomic bomb explosion in Nagasaki thirty miles to the south despite the mountainous terrain that had helped Nagasaki to confine part of the explosion.

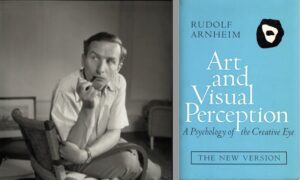

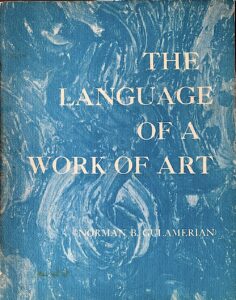

In March 1946, after six months in Japan, Gulamerian boarded the USS Monadnock and returned to San Francisco. By April he was back in Brooklyn, and completed the year he had missed at the High School of Music & Art. In the Fall of 1947, he entered The New School where he was highly stimulated by classes taught by Rudolf Arnheim [1904–2007]. Even as a teenager, Gulamerian was aware that Arnheim was the leading psychologist on visual perception investigating the relationship between sensory visual imagery and cognition. Taking advantage of studying under him turned out to be a transformative experience. Arnheim recognized that Gulamerian, at 20, already possessed a significant knowledge of art history, materials, and techniques, which made clear that his experiences were far above those of other students. The elder professor appreciated the student who probed, contested, and critiqued his theories. The professor united with the young artist he respected as a valued scholar, and who consistently served as a significant sounding board for Arnheim’s books, including his magnum opus — Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye — published in 1954. Personal copies of Arnheim’s subsequent editions — creased, taped, and dog-eared — are littered with Gulamerian’s penciled clarifications and qualifying remarks. The vast Gulamerian Archive provides ample evidence of a close professional bond that lasted fifty years, including his critiques of Arnheim’s other two major books, Visual Thinking (1969) and The Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts (1982). The archive contains the publisher’s draft copies of both books, also profusely annotated with his detailed assessments. Arnheim, in turn, critiqued a draft of Gulamerian’s The Language of a Work of Art (1963).

When Gulamerian matriculated at Brooklyn College in 1949, he was delighted to learn that the new chairman of psychology was Professor Harry Helson [1898–1977], whose special interest was laboratory work in the optics of the perception of color and form.2 As with Arnheim, Gulamerian would form a lasting relationship with Helson. For example, in 1965 Helson asked Gulamerian to present a paper on visual perception at the 73rd Annual National Convention of the American Psychological Association. It is crucial to understand that Gulamerian’s advantage of engaging in such extensive scientific reciprocation with two prominent psychologists of visual perception speeded the crystallization of his own unique style. But with no time or interest to seek gallery representation, his trailblazing masterpieces of Figurative Expressionism were destined to remain separate from the movement and unseen during his lifetime.

The Dual Challenge of Science and Pathos

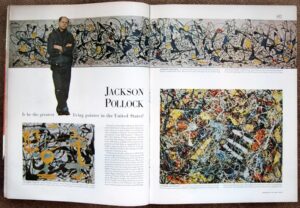

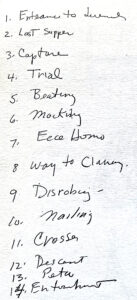

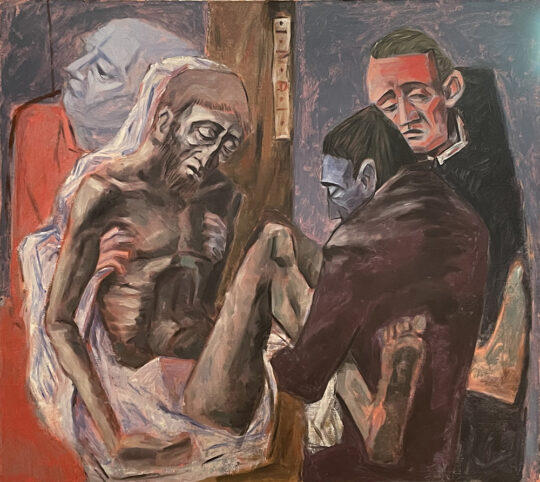

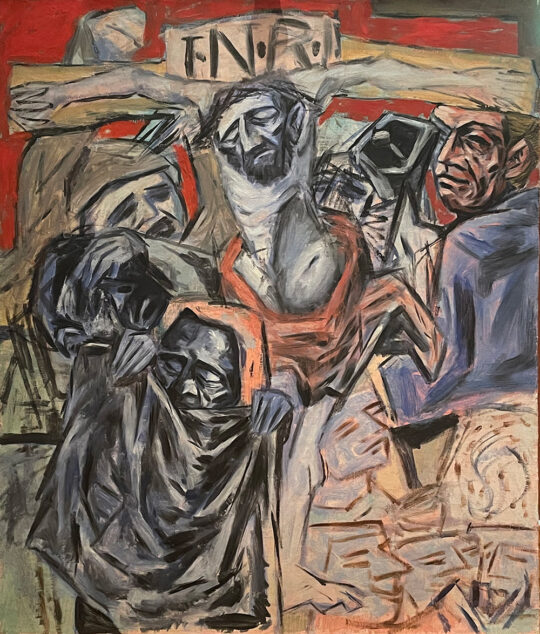

Gulamerian’s artistic maturation occurred amidst a zeitgeist of a revolution in styles that had begun at the end of World War II when the Abstract Expressionists of the New York School wrested from Paris the title of capital of the art world. During that summer of 1949, a seminal article in LIFE magazine featured a two-page spread showing the irascible Jackson Pollock in front of one of his big drip-action paintings (left). The headline read: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” That headline could be interpreted as almost mocking — and it was certainly provocative. It was also in 1949 when two other significant abstract painters were attracted to join the faculty of Brooklyn College: Ad Reinhardt [1913–1967] and Burgoyne Diller [1906–1965]. While Gulamerian was stimulated by their approaches to abstraction, he was more driven by two distinct catalysts. On one hand, Arnheim and Helson continued to reinforce his scientific explorations of visual perception. On the other, he was compelled by the powerful pathos inherent in The Passion. The germination of his choice must in part be credited to his mother because, as a devout member of the Armenian Church, she read passages from the Bible to her young son every night. However, his ambitious decision was made not out of pious devotion. The boy never grew to be devoutly religious and was instead a true nonconformist with contrarian views on organized religion. By 1949 he had become a combination of psychologist, historian, and painter intent upon tapping these three disciplines to reach the deepest emotions of the human psyche. After all, for centuries the Church had used the Bible’s recounting as a powerful means of commanding the faithful. For the Church, it was the many stages of The Passion describing Christ’s gruesome suffering that made the most indisputable and irresistible argument. Gulamerian not only chose to tackle this emotional subject matter but interpret it by developing his own distinctive style of Figurative Expressionism. He also chose to focus on the most disturbing scenes of the 14 Stations of the Cross: the mocking of Christ by the bloodthirsty mob as he lugged his cross to Calvary; the excruciating slow death of the Crucifixion itself; the pathetic descent from the Cross; and the poignant Pietà.

Gulamerian’s artistic maturation occurred amidst a zeitgeist of a revolution in styles that had begun at the end of World War II when the Abstract Expressionists of the New York School wrested from Paris the title of capital of the art world. During that summer of 1949, a seminal article in LIFE magazine featured a two-page spread showing the irascible Jackson Pollock in front of one of his big drip-action paintings (left). The headline read: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” That headline could be interpreted as almost mocking — and it was certainly provocative. It was also in 1949 when two other significant abstract painters were attracted to join the faculty of Brooklyn College: Ad Reinhardt [1913–1967] and Burgoyne Diller [1906–1965]. While Gulamerian was stimulated by their approaches to abstraction, he was more driven by two distinct catalysts. On one hand, Arnheim and Helson continued to reinforce his scientific explorations of visual perception. On the other, he was compelled by the powerful pathos inherent in The Passion. The germination of his choice must in part be credited to his mother because, as a devout member of the Armenian Church, she read passages from the Bible to her young son every night. However, his ambitious decision was made not out of pious devotion. The boy never grew to be devoutly religious and was instead a true nonconformist with contrarian views on organized religion. By 1949 he had become a combination of psychologist, historian, and painter intent upon tapping these three disciplines to reach the deepest emotions of the human psyche. After all, for centuries the Church had used the Bible’s recounting as a powerful means of commanding the faithful. For the Church, it was the many stages of The Passion describing Christ’s gruesome suffering that made the most indisputable and irresistible argument. Gulamerian not only chose to tackle this emotional subject matter but interpret it by developing his own distinctive style of Figurative Expressionism. He also chose to focus on the most disturbing scenes of the 14 Stations of the Cross: the mocking of Christ by the bloodthirsty mob as he lugged his cross to Calvary; the excruciating slow death of the Crucifixion itself; the pathetic descent from the Cross; and the poignant Pietà.

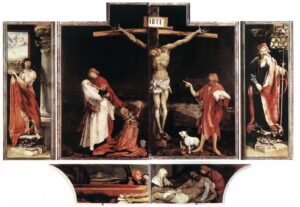

From an art historical viewpoint, Gulamerian was undaunted. He was already steeped in the Old Masters from the 14th to the 17th centuries in Italy, Holland, and Germany and the apex of pathos they achieved in their paintings. In particular, Grünewald’s famous Isenheim Altarpiece, a triptych painted in the early 16th century, exerted a profound impact upon him. He was awestruck by the pain expressed in the crucified Christ, suffering not only from the nails driven through his expressively writhing hands and bloody feet but by the plague-type sores blanketing his body. Here he saw a master who pulled out all the emotional stops.

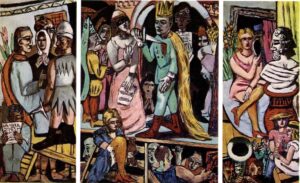

It must be pointed out that even though Abstract Expressionism was all the rage in the mass media during Gulamerian’s post War stint at Brooklyn College, far more artists were pursuing Figurative Expressionism. Gulamerian appreciated the bravura of non-objective painting but was more interested in the overriding challenge of defining the powerful scientific axioms that were the key to understanding what made a painting of any style compelling. Gulamerian was particularly drawn to the figurative style and compositions of Max Beckmann [1884–1950], who had just become a professor at the Brooklyn Museum School in the Fall of 1949. A major figure in German Expressionism, Beckmann had just finished two years of teaching at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts. Gulamerian wrote that the painting by Beckmann that influenced him the most was The Actors, a triptych painted in 1941–42 while in exile in Amsterdam. This depiction of a theater set during rehearsal is energized by its numerous figures, and the whole composition invites viewers to carefully examine the roles of all the players, both above and beneath the stage. It was this type of urgent and energetic compositions that presaged figurative expressionism and served as one of the catalysts for Gulamerian’s masterpieces — three large triptychs. From that point on, the theme of The Passion as a stage play was just the type of spirited platform upon which Gulamerian would target his creativity. The central objective of his artistic quest was to figure out how the theme, composition, color scheme, and expression of his paintings could most effectively appeal to a person’s psyche. Therefore, it was natural to continue his explorations of visual perception with Arnheim and Helson during his own development as a painter. As artist, psychologist, and historian he was trying to interpret the aesthetic theory of what the revolutionary British art critic, Clive Bell, referred to in 1914 as “significant form” — that is, art must have the capacity to elicit an emotional response from the viewer.

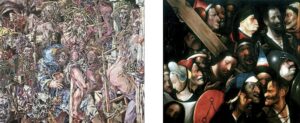

The third painting that Gulamerian cited as greatly impressing him was that of an early 16th century follower Hieronymus Bosch entitled Christ Carrying the Cross. The composition is packed with major characters, including Veronica displaying the fresh relic of her veil used to wipe the blood from Christ’s brow. Simon of Cyrene suffers under the weight of the cross, and the two thieves also facing Crucifixion are beset by hecklers. In Bosch, he saw an unrelenting nightmarish surrealism in the ghoulish faces of taunting characters — and in Pieter Brueghel he reveled in a cartoonish depiction of a society spinning tales of debauchery, sex, and death. Gulamerian wrote that high on his list of works by other Old Masters he most respected were Albrecht Dürer’s drawings and woodcuts of The Passion, Rembrandt’s etchings and paintings, and the paintings and drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and Cézanne — all of which provided forms of that would energize his own paintings.

Solving Artists’ Material Needs

Toward the end of his first semester in 1949, Gulamerian found himself at a crossroads, brought on by his frustration over the difficulty in finding high quality linen canvases. “He wanted to prime his own canvases, but he couldn’t find any linen, so he imported a roll from Belgium,” said Jennifer Pagano, his youngest daughter. “His brother said to him, ‘If you can’t find it, other painters can’t either.’” Norman’s desire to fulfill his own need as well as that of other artists incited him to unite with his older brother, Harold, a chemist. Together, they determined that no more time could be wasted in classes, and they became devoted partners who risked dropping out of college to found a start-up venture in the basement of their family home in Brooklyn. As a painter with his own personal requirements for canvas, Gulamerian found his answer in a producer of finely woven linen in Belgium who was receptive to his specifications. Success came quickly to the company the brothers called Utrecht Linens, named after the nearby New Utrecht Avenue.

Norman’s specifications would soon drive the creation of their lines from linens to both oil and acrylic pigments, with production managed by Harold. With Norman leading marketing and promotion, Utrecht quickly won a cult-like following among artists. By 1953, the success of Utrecht Linens allowed the Gulamerians to open an office at 119 West 57th Street located directly across the street from Carnegie Hall. In 1957, they were the first to invent an acrylic gesso for priming canvases. The next year, they moved the business to Bush Terminal (now Industry City) in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, where they developed and milled their own oil and acrylic pigments. Gulamerian wrote every Utrecht catalogue, determined to make them educational tools on how to use artist’s materials as well as appreciate their context in art history. Glowing testimonials about Utrecht’s quality flowed from American masters such as Max Beckmann, Hans Hofmann, George Grosz, and Reginald Marsh. Hans Hofmann wrote, “I have been preparing my own canvases with Utrecht linens with the greatest satisfaction for years. It’s wonderful texture, painting surface, and permanence are of the highest order.” As their product line kept expanding into the 1960s, the company was re-named the Utrecht Art Supply Corporation. In 1966 Norman realized that because he was the manufacturer, he could further enhance his good standing with artists by opening retail stores. His first store, on Third Avenue near Cooper Union in NoHo, quickly attracted the area’s large population of artists who discovered that buying direct from the manufacturer meant the most favorable prices. During the 1970s, Gulamerian opened many new stores around the country. His was an aggressive marketing strategy that made artists happy because the prices were discounted by thirty percent — but caused many art supply shops to go out of business. By the 2000s, the expansion of Utrecht Art Supplies included 45 retail stores. In 1997, the Gulamerian brothers, both in their mid-seventies, sold their company to a private investment firm. Gulamerian retired to his studio. (In 2013, Blick Art Materials acquired the company as well as its historic paint manufacturing mill in Brooklyn.)

Norman’s specifications would soon drive the creation of their lines from linens to both oil and acrylic pigments, with production managed by Harold. With Norman leading marketing and promotion, Utrecht quickly won a cult-like following among artists. By 1953, the success of Utrecht Linens allowed the Gulamerians to open an office at 119 West 57th Street located directly across the street from Carnegie Hall. In 1957, they were the first to invent an acrylic gesso for priming canvases. The next year, they moved the business to Bush Terminal (now Industry City) in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, where they developed and milled their own oil and acrylic pigments. Gulamerian wrote every Utrecht catalogue, determined to make them educational tools on how to use artist’s materials as well as appreciate their context in art history. Glowing testimonials about Utrecht’s quality flowed from American masters such as Max Beckmann, Hans Hofmann, George Grosz, and Reginald Marsh. Hans Hofmann wrote, “I have been preparing my own canvases with Utrecht linens with the greatest satisfaction for years. It’s wonderful texture, painting surface, and permanence are of the highest order.” As their product line kept expanding into the 1960s, the company was re-named the Utrecht Art Supply Corporation. In 1966 Norman realized that because he was the manufacturer, he could further enhance his good standing with artists by opening retail stores. His first store, on Third Avenue near Cooper Union in NoHo, quickly attracted the area’s large population of artists who discovered that buying direct from the manufacturer meant the most favorable prices. During the 1970s, Gulamerian opened many new stores around the country. His was an aggressive marketing strategy that made artists happy because the prices were discounted by thirty percent — but caused many art supply shops to go out of business. By the 2000s, the expansion of Utrecht Art Supplies included 45 retail stores. In 1997, the Gulamerian brothers, both in their mid-seventies, sold their company to a private investment firm. Gulamerian retired to his studio. (In 2013, Blick Art Materials acquired the company as well as its historic paint manufacturing mill in Brooklyn.)

The Challenge of Balancing Three Pursuits — and a Family

At this point, it would be easy to make the big mistake of categorizing Gulamerian as a struggling artist who instead became a corporate suit. But he effectively kept his leadership of Utrecht Art Supplies separate from his triple pursuit of painter, psychologist, and historian. He accepted the business as a necessity that imposed the bothersome inconvenience of having to restrict to nights and weekends the time he could devote to his original three passions. In addition to his ongoing challenges to the academic views of leading psychologists such as Arnheim and Helson, he evoked debate with eminent art historians such as Erwin Panofsky. For example, even when Gulamerian was mounting his first big success for Utrecht in 1953, he reached out to Panofsky — who was teaching at Princeton and had just published his seminal treatise, Early Netherlandish Painting. Gulamerian sent him a challenging essay with his own in-depth interpretations of the symbols and iconography of Bosch and Breughel. Panofsky replied, “In my opinion, no one but a Dutchman or Fleming can successfully solve the riddles of both Bosch and Breughel, because the images of these painters is so deeply impregnated with verbalism (proverbs, etc.) that no outsider can fully grasp their allusions…I don’t mean to be dogmatic in matters pertaining to Bosch and Breughel and do not mean to deny that your essay may contain some valuable suggestions; but I am afraid that it would take many more years of study to make a case like this really convincing.”3 Gulamerian researched in depth the Old Masters who inspired him. His membership card for the Pierpont Morgan Library shows that he began doing research there beginning in 1956 — and he renewed year after year thereafter.

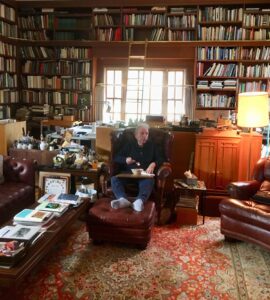

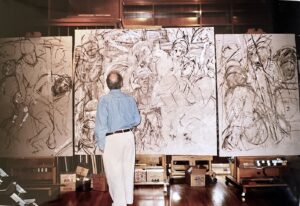

In 1963, Gulamerian found himself at a funeral in St. Louis when he met his future wife, Mary Alexander. She was an exuberant young widow with five children, on her own after her husband had died of a sudden heart attack. After meeting again two years later, he began to send her frequent love letters from New York. One letter, early on, included a marriage proposal. It was simply a watercolor showing a male bird on the ground looking up at a tree, where a female bird attended to her five baby birds. After finally marrying in 1969, they settled into an expansive home in New Jersey. They later added an art studio and library large enough to accommodate his monumental triptychs. During this period, his Utrecht Art Supply company was greatly expanding its product line and within a few years began opening retail stores around the country. Yet, despite such great commercial success, Gulamerian always found a way to dedicate time to pushing the underlying scientific theories of psychology of visual perception in painting as he developed his massive triptychs. It is equally astonishing that at the same time this polymath with so many passions made the time to balance his life as a dedicated father and grandfather. As his five grandchildren were growing up, he consistently postulated how wonderful they were. His middle daughter Eve recalled “He always said, ‘I wouldn’t change one thing about any one of them. Not one thing, they’re perfect.’” He went to their piano and orchestra recitals, holiday school concerts, and graduations. He particularly loved taking the whole family out to dinner and sending them baskets from Zabars. She added “He knew so much about movies, from John Houston to ‘Terminator 2.’ He loved comedies like Arthur and any incarnation of Sherlock Holmes. He loved Benny Hill. He loved to laugh. He loved life.” His daughter Jenny remembered “You could always find him in his studio, Bach blasting from the speakers, ‘Citizen Kane’ or ‘Murder She Wrote’ blaring from the TV, as he sat quietly, notebook on his lap, writing or drawing, and studying the canvases on the easels. Even if you interrupted all that, he was happy to see you and ready to listen to whatever you wanted to talk about.”

When returning to research and writing, Gulamerian found Arnheim to be his most enduring collaborator. For decades, they were mutual sounding boards about visual perception. One typical example appears in 1961 when Arnheim was in Europe conducting research for his The Genesis of a Painting: Picasso’s Guernica. Gulamerian sent him a letter alerting him that Picasso’s drawings of a horse’s head in Guernica were remarkably similar in style to a horse’s head drawn by Rembrandt in the fourth and final state of the etching The Three Crosses. “They both indicate the tendency toward simplicity by two different artists of the same subject.” His conclusion was “This factor of flexibility I believe can function as an additional control in iconographical analysis.” Just after the book was published in 1962, Arnheim wrote a confession to Gulamerian. Despite his exhaustive analysis of the many stages of drawings and paintings he used to analyze Picasso’s creative process that led to the finished Guernica mural, he had missed an important element: a door at the far right edge of the masterpiece. Gulamerian wrote a note to himself, “This is another example — even with a superior trained eye as Arnheim — that there are features that are structurally embedded in the work that require special attention to discover in very complex work — [because] the probability increases of the difficulty of discovering hidden features. As Roger Fry in his last lecture indicated, a method of analysis must be developed because of the complexity of works of art.”4 Gulamerian’s own compositions, packed with active figures, invite viewers’ concerted exploration to discover his hidden elements, and how their roles and special meanings effect the whole.

Arnheim also kept up with Gulamerian’s artistic quest, weighing in on the grand undertaking of The Passion paintings. In 1966 he wrote: “It was of great interest for me to see the considerable progress in your conception of the Passion. While the cast of the scene is now closer to the tradition, the composition has gained considerably in overall unity and in the clear-cut expression of the particular figures, especially the Madonna. Also, the large face on the kerchief of Veronica is striking, by the note of unrealistic superhuman size it introduces to the scene.”5

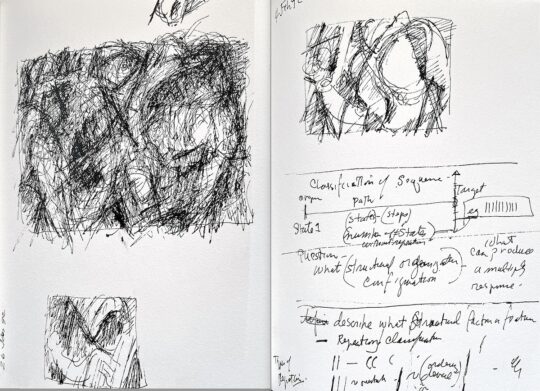

Mary Gulamerian played vital roles, not only as the family’s director but as chief organizer of her husband’s prolific research and writing. She also used the typewriter to transcribe all of his hand-written thoughts. For example, in 1968, while working on a greatly revised edition of his The Language of a Work of Art, Gulamerian typed a five-page letter to her about the problems he anticipated would become clear the role of artificial intelligence in art. A dozen years before the “AI boom” of the 1980s, he admitted, “I do not know anything about computers,” and then laid out his critique about an article in The New York Times “about using a computer in judging differences between works. It is far from being successful but one day maybe it can be. This is what I have had in the back of my mind for years. I talked about it with Arnheim two years ago — That if my theory can be worked out in real detail, and if it makes sense, we can program a computer with the ‘standard of aesthetic value, and the machine can make the judgement for us….The major issue of this problem is how do we measure the originality of a style without relying on the statistical approach, which is truly meaningless.” Adding that “an intellectual solution in itself is also meaningless.” He continued, “I know what Arnheim would say to me now: That as usual, I am trying to put in too much into what I write, trying to solve too many problems, trying to explain as much as possible….Well, with this second edition I will try to deal with the issues Arnhem has tried to solve — to redefine these problems within a concept of ART, not psychology. [I will] introduce new issues, not a re-hash of Arnheim or old views.” 6

Mary Gulamerian played vital roles, not only as the family’s director but as chief organizer of her husband’s prolific research and writing. She also used the typewriter to transcribe all of his hand-written thoughts. For example, in 1968, while working on a greatly revised edition of his The Language of a Work of Art, Gulamerian typed a five-page letter to her about the problems he anticipated would become clear the role of artificial intelligence in art. A dozen years before the “AI boom” of the 1980s, he admitted, “I do not know anything about computers,” and then laid out his critique about an article in The New York Times “about using a computer in judging differences between works. It is far from being successful but one day maybe it can be. This is what I have had in the back of my mind for years. I talked about it with Arnheim two years ago — That if my theory can be worked out in real detail, and if it makes sense, we can program a computer with the ‘standard of aesthetic value, and the machine can make the judgement for us….The major issue of this problem is how do we measure the originality of a style without relying on the statistical approach, which is truly meaningless.” Adding that “an intellectual solution in itself is also meaningless.” He continued, “I know what Arnheim would say to me now: That as usual, I am trying to put in too much into what I write, trying to solve too many problems, trying to explain as much as possible….Well, with this second edition I will try to deal with the issues Arnhem has tried to solve — to redefine these problems within a concept of ART, not psychology. [I will] introduce new issues, not a re-hash of Arnheim or old views.” 6

A Dynamic Passion Play

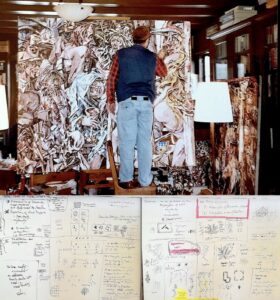

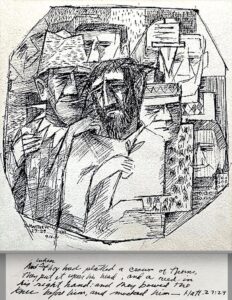

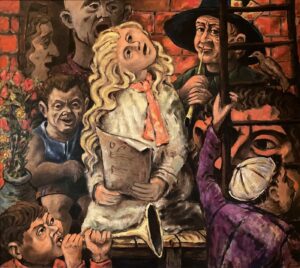

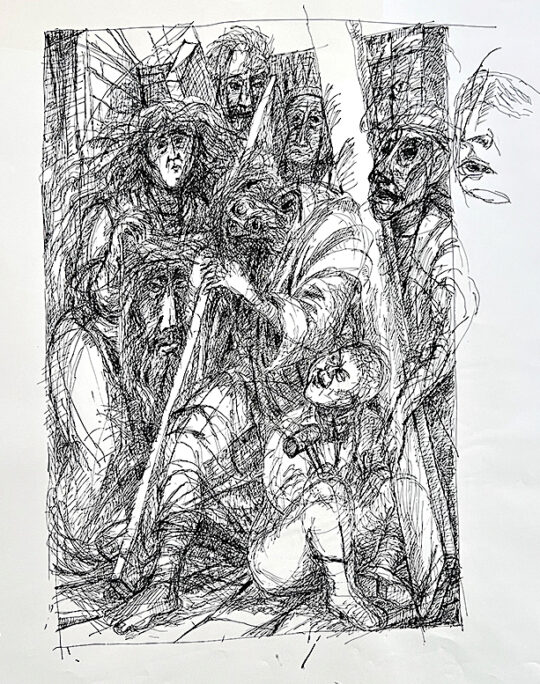

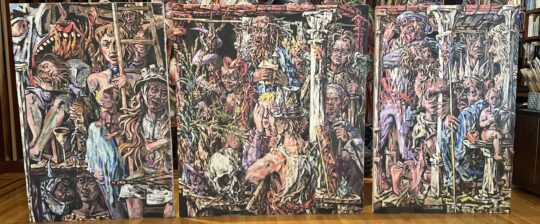

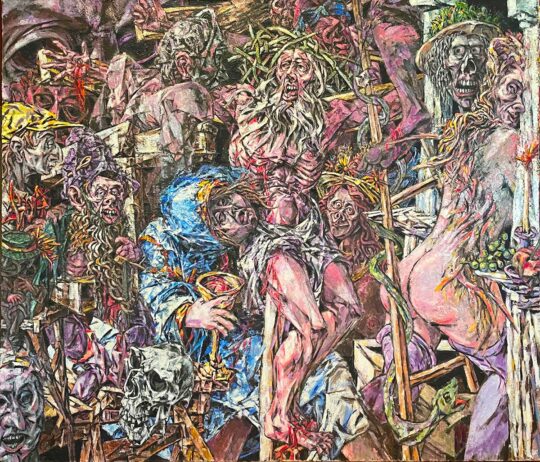

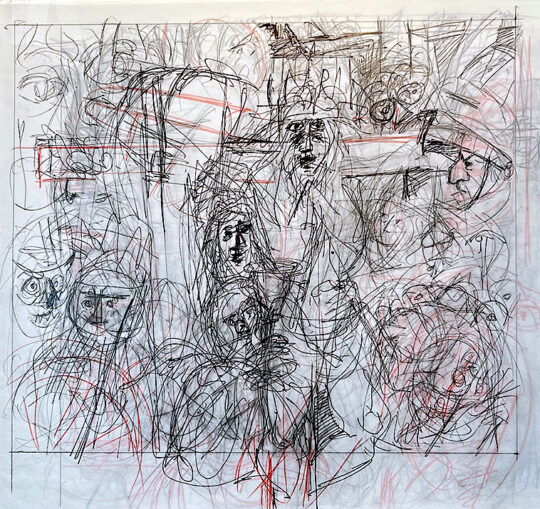

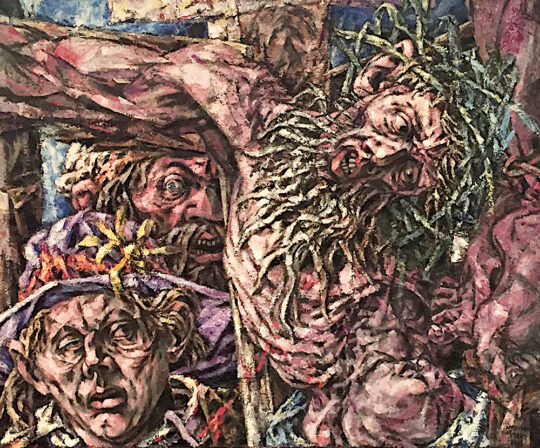

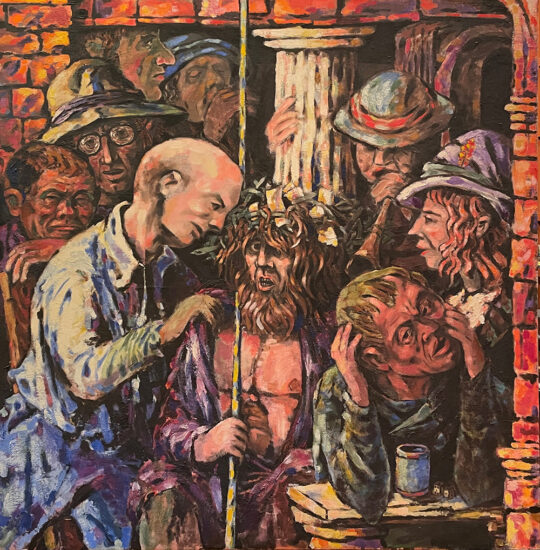

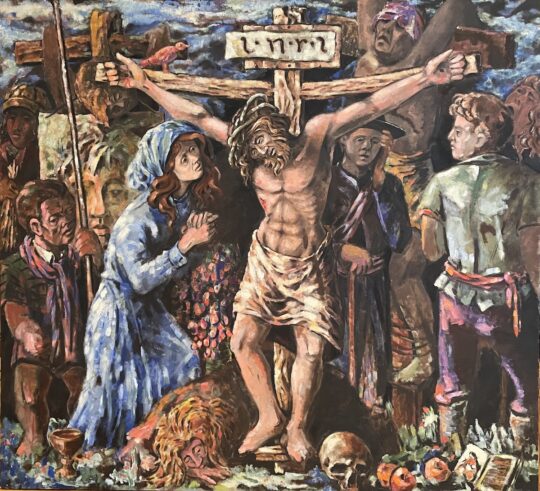

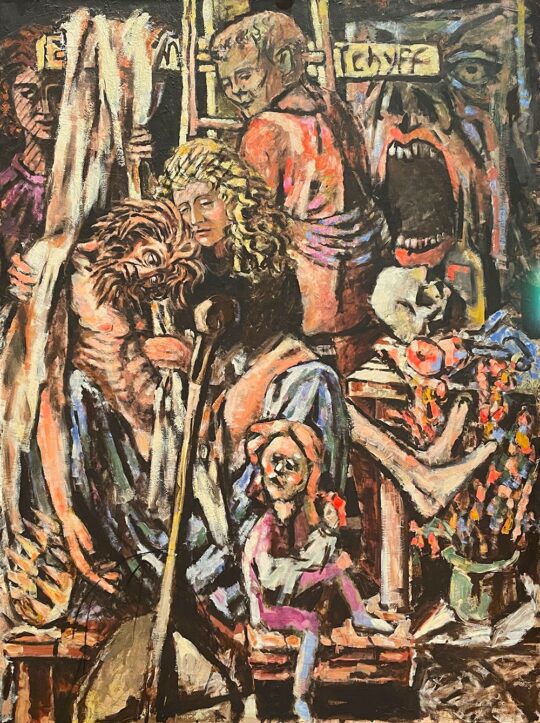

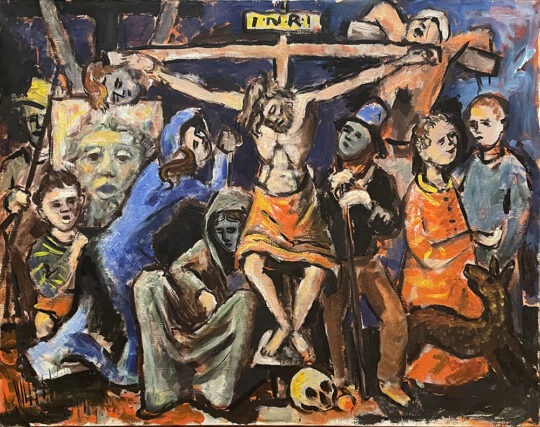

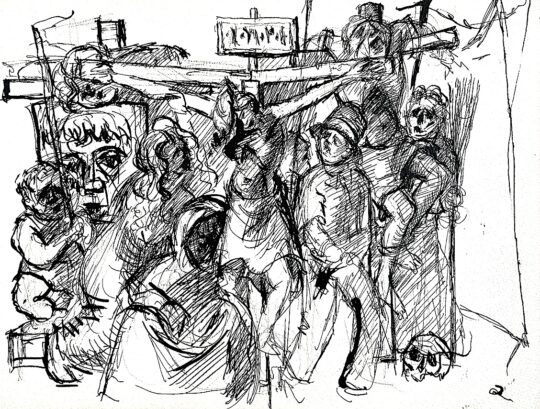

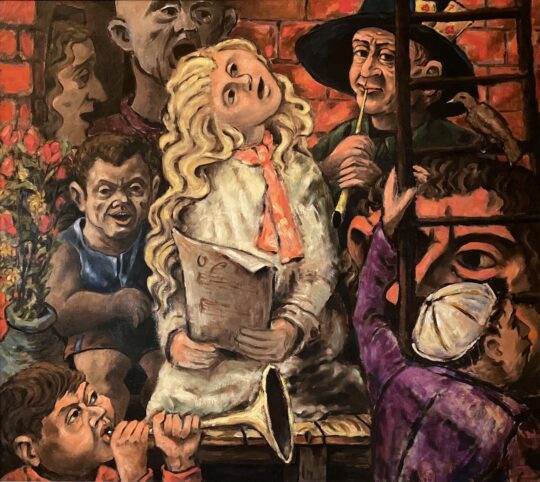

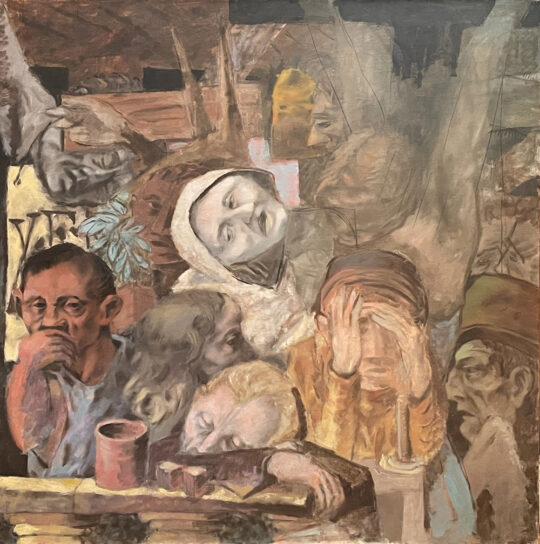

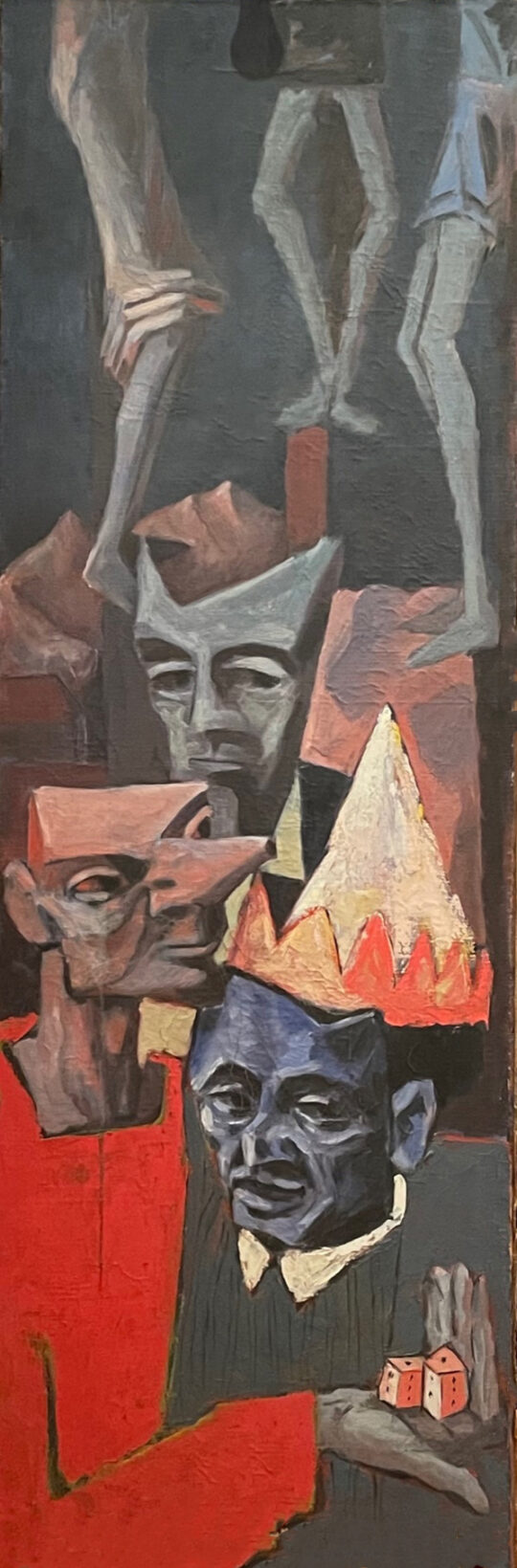

Humanism, tempered by psychology, were the driving forces of Gulamerian’s attraction to The Passion as his subject, approaching it with his own style of Figurative Expressionism. He was determined to make accessible a very difficult subject matter by eliciting visceral emotional responses in a different way, separate from that of timeworn religious iconography. He instead had his characters play dramatic roles, just as if they were actors on a modern stage. His numerous drawings and some smaller canvases seem to be out-takes from the play he has created. In some, he even points out the steps of the stage and its floorboards. And, just as Max Beckmann did in The Actors, he even shows figures beneath the stage. Gulamerian’s preparatory drawings are illuminating because they bring us backstage to reveal spotlights, makeup artists, actors, and camera crews. In one preparatory drawing for a triptych, he noted: “Scene is Christ preceded by a carnival-like show — to be followed by another.” Another drawing indicates that the dressing room is located toward the rear of the stage, jazz players are to perform at the front steps, and the space beneath the stage is hell. The margin of another study shows an easel holding a sign, “Act 1.” Indeed, more clever distractions include tambourine and horn players who accentuate the energy of Carnaval in Brazil or the Day of the Dead in Mexico — and one study is annotated, “Mardi Gras.” Gulamerian was sure to insert everyday people in his compositions. One recurrent character wears a baseball cap and a striped shirt. Others wear glasses. But there are also plenty of bizarre and surreal figures jammed into his triptychs. Some lurk in the background, including a giant grotesque face from hell spouting flames while gobbling up the crowd. The tortured figure of Christ is typically centrally positioned among the swirling masses of comingled figures. He may be flanked by cadaverous figures and even pole-dancing nudes.

Gulamerian’s mastery lies in his ability to express the emotion of figures through a merging of technique, color relationships, and vivid symbolism — all energized by directional forces working together. His cyclonic volumes of figures — composed of animated lines, fleshy forms, and radiant color — are visually weighted, igniting the sense of visceral emotion. Both surreal and abstract, the density of these figures does not generate a claustrophobic atmosphere but instead their colorful and energetic flow invites closer examination, inviting us to follow the actors in this play. For example, the figure of Christ always blends with the colors, textures, and movements of the many figures that flow with him through the compositional whole. Stepping back to contemplate the sweeping views of each of these large triptychs is breathtaking. Squint at these human masses and you’ll see an AbEx painting.

In the event that the Broadway hit musical “Jesus Christ Superstar” comes to mind, it should be noted that Gulamerian never saw that Broadway sensation even after its opening in 1971. After all, it was more than two decades earlier when he had become focused on presenting The Passion as a stage play on canvas. Ultimately, Gulamerian’s plays are reminders that the real issue taking place at center stage is that we must become aware of our human foibles.

The Persistence of The Passion in Figurative Expressionism

When Gulamerian matured as an artist during the 1950s, Figurative Expressionism was becoming a movement, albeit an unorganized one. But its roots were set in Boston during the Great Depression, under Hyman Bloom [1913–2009] and Jack Levine [1915–2010]. Early in 1942, when Gulamerian was fifteen and apprenticed to Frederick Taubes, war was raging in the South Pacific but in New York the Museum of Modern Art hosted Bloom and Levine in the exhibition “Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States.” Had Gulamerian read the exhibition catalogue, he would have approved of Levine’s description of his approach to the figure: “Movement in my canvases embraces every object as well as atmosphere. Dramatic action on the part of the characters is latent. I distort images in an attempt to weld the drama of man in his environment.” By the 1950s, when Levine had become recognized as the leading Figurative Expressionist in New York, he became friendly with the young artist who had made Utrecht Linens successful. Levine even provided a testimonial for Gulamerian, saying that the company’s finely woven canvas was the best he had ever used.

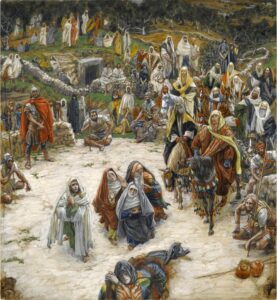

It was also in the early 1950s when the vigorous brushwork of David Parks led to a figurative movement in the Bay Area. Its wave motion arrived in Chicago with Philip Guston and the Monster Group. Each city was an influential epicenter, and many of its figurative painters were inspired by the works of legions of Old Masters who had tackled the themes of The Passion. This is a subject that has remained consistently inspiring and challenging, regardless of the often-disparate psyches of artists — from pious adherents to cynical atheists — who have expressed that emotion. Gulamerian the historian studied who. Gulamerian the psychologist studied why. Gulamerian the painter determined how. He understood that during the Renaissance the predominant subject matter was naturally centered upon The Passion. That’s because the Catholic Church seized such powerful imagery to exert its tremendous social and political power. Along with its wealthiest patrons — most notably, the powerful Medici family — the Church commissioned most paintings, frescoes, and sculptures. Gulamerian also carefully studied how, in the following centuries, Old Masters such as Rembrandt, Dürer, Bosch, Brueghel, Rubens, and others — moved from the flat frontal plane of the Crucifixion by devising compositions with new viewpoints, even using the motion of crowds to reinforce the emotional intensity of their subject to create profound humanist statements. Gulamerian’s pursuit, both artistic and scientific, was aimed at understanding how structures, colors, and techniques were employed — knowing that the most effective combination of these key elements would draw a compelling emotional response. For example, he admired Tiepolo’s Crucifixion of 1745–50 (left), for breaking with the typical frontal viewpoint by pulling the viewer in obliquely toward the three crosses amidst an active crowd. During the first half of 19th century France, Eugene Delacroix also broke loose, but with vibrant color and even more energetic brushwork in his Crucifixions — yet he was known as a religious sceptic. In contrast, he was followed by Gustave Doré, a devout Catholic who in 1866 became the most famous artist in the world with the publishing of his dramatic illustrations that composed his voluminous Holy Bible. A later French artist, James Tissot, more a spiritualist than a devout Catholic, painted his break-out What Our Lord Saw from the Cross (below, ca. 1890) owing to its unusual perspective of portraying the large crowd that Jesus would have seen looking down during his Crucifixion. Gulamerian appreciated this painting at the James Tissot exhibition, “The Life of Christ,” held at the Brooklyn Museum in 2009–10. Paul Gauguin was also of Catholic upbringing, but even when he painted his Yellow Christ in 1889, he was not religious but instead a spiritualist more attracted to the theosophy of Madame Blavatsky. During this same period, James Ensor turned to religious themes featuring Christ even though he was an atheist and called himself a madman. Gulamerian knew why Ensor was so deeply influenced by Bosch and Brueghel because he saw Ensor’s paintings as surreal plays enlivened by skeletons, carnival masks, and grotesque figures.

In light of Gulamerian’s deep knowledge of art history, it would be too convenient to assert that his religious upbringing caused him to focus his artistic career on the anguishing story of the twelve stations of The Passion. Something else mattered much more. As a psychologist of visual perception, he was relentlessly determined to unravel the complicated reason why the Crucifixion had become one of the world’s most powerful symbols. Moreover, in Edvard Munch’s The Scream of 1893 he saw a painterly act that was the crucial historical harbinger of a new freedom of figural expression. Thereafter, modern artists continued to embrace new conceptual approaches and radical styles in their quest to capture emotions as well as human movement. The Cubism of Picasso and Braque in France was seminal, too, especially in tandem with the Futurism of Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini in Italy. Then, just twenty years after Munch painted The Scream, Marcel Duchamp’s cubist Nude Descending a Staircase created an uproar at the 1913 Armory Show in New York. After Munch had pried open a Pandora’s box, the Cubists and Duchamp pushed further, releasing what would eventually be known as Figurative Expressionism. The figure in art would never be the same. Besides these artists who were catalysts of change, few others would ever have so great an impact on the course of modern figure painting.

An Obsession for The Passion

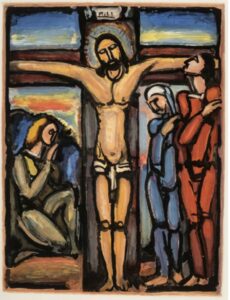

While the heartrending imagery of the Crucifixion has served as conceptual provocation for many painters to create their own interpretations, very few in the 20th century ever made it their primary focus. Among them, Georges Rouault [1871–1958] was such a devout Catholic that late in life, in the 1930s, he became obsessed with painting scenes from the Passion. It has often been cited that Rouault stated that his “only ambition is to be able to paint a Christ so moving that those who see Him will be converted.”7 Stylistically, he created emphasis with his signature thick black outlies that testified to his early work in stained glass. In 1938 the Museum of Modern Art held an exhibition of his prints, including the color aquatints from his Passion Series. At the same time, Abraham Rattner [1893–1978] was studying in Paris and was greatly influenced by Rouault’s work. After returning to New York the next year he soon became a well-known painter of abstract figures. Gulamerian must have been aware of him because Rattner taught at the New School from 1947 to 1955. Rattner was also one of many Jewish artists, including his friend Ben-Zion, who interpreted the emotional scenes of The Passion. Of his Crucifixion scenes, he wrote, “It is myself that is on the cross, though I am attempting to express a universal theme — man’s inhumanity to man.”8

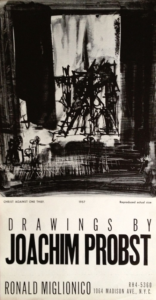

Another New Yorker who saw himself on the Cross was the self-taught Joachim Probst [1913–1980] who, beginning in the early 1940s became obsessed with the subject. Both Rembrandt and Rouault were the strongest influences upon his style. However, his bouts with schizophrenia and his myopic focus on the Crucifixion resulted in a chronic morbidity that permeated his life. This incited the denizens of Greenwich Village to label him “the Christ painter,” and by the early 1950s he had become a mythic character known as “the Bohemian of Greenwich Village.” From the mid-1950s through the 1960s, the Greer Gallery implemented a strategy of touring his paintings across the nation. He made television appearances and became a craze with Hollywood collectors.

Conclusion

Gulamerian was an anomaly, a rara avis of the 20th century art world. He defied the notion that scientific research and the act of painting were irrevocably incompatible. Compounding the paradox, he is the only American painter who was also a published theorist on the psychology of visual perception and expression. He blew apart and then reassembled the paradigm of what is expected of a painting. Moreover, he was not only one of the country’s leading experts on artists’ materials and techniques but also the entrepreneur who built the country’s largest and most successful art supplies company. While his completion of the final triptych was the apotheosis of his career, all three of his large triptychs speak together as his magnum opus and vault him to the forefront of Figurative Expressionism in America. Humble and unassuming, he may never have fully realized the extent of his accomplishments before he contracted the coronavirus and passed away on April 13, 2020. Indeed, Gulamerian provided an insight into his life as artist when at age 82, more than ten years after selling Utrecht, he was interviewed for the company’s 60-year Anniversary catalogue. The new owner asked him to cite his most favorite day in his long career of building Utrecht. Gulamerian simply replied, “The day I left.”

— Peter Hastings Fal

NOTE:

Click on the official website of the Norman Gulamerian Estate Collection to view more works.

FOOTNOTES

1 Carmel, Mona. “Palette Patter” column in Music & Art (1944)

2 American Journal of Psychology (Mar. 1979, vol. 92, No.1, pp.153–160)

3 Panofsky to Gulamerian, 2 Feb 1953. Erwin Panofsky [1892 –1968] taught at Princeton 1935–1968. Panofsky first gained recognition for his Studies in Iconology: Humanist Themes in the Art of the Renaissance (1939), followed by The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (1943). His most influential book was Its Origins and Character (1953), which became an important resource for scholars of the iconography of the Renaissance and Northern Europe — a concept later expanded upon in his Meaning in the Visual Arts (1955).

4 Arnheim, Rudolf. The Genesis of a Painting: Picasso’s Guernica (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962)

5 autograph letter from Rudolf Arnheim 7 Jan 1966

6 typewritten letter to Mary Gulamerian with pen & ink sketches, signed and dated 17 April 1968

7Georges Rouault: The Passion (Bloomington: Lilly Library of Indiana University, 1982)

8 Sacred Art Pilgrim (online art magazine)

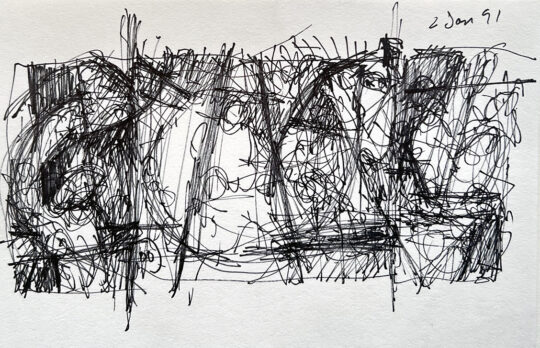

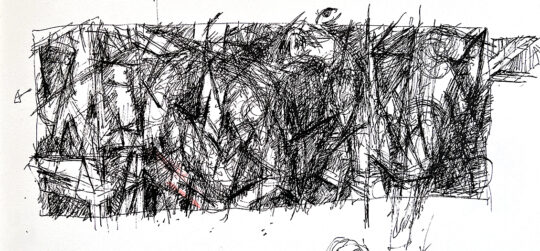

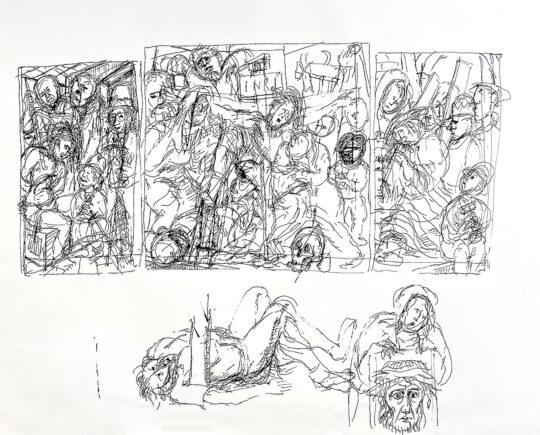

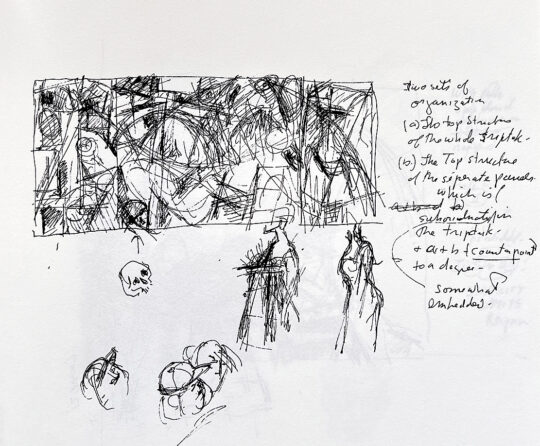

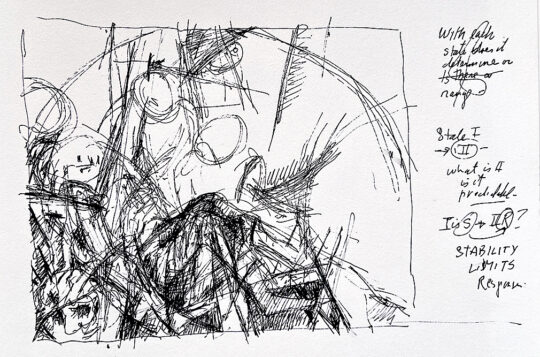

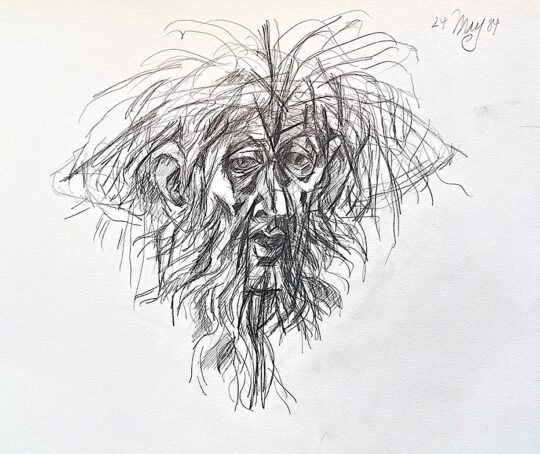

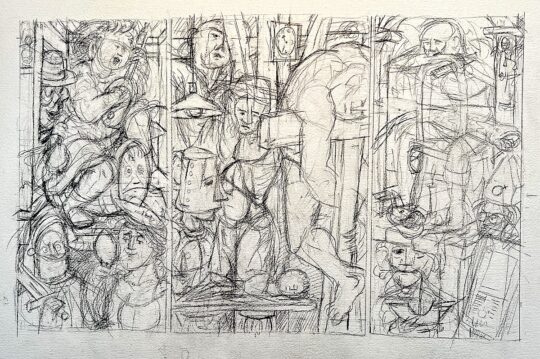

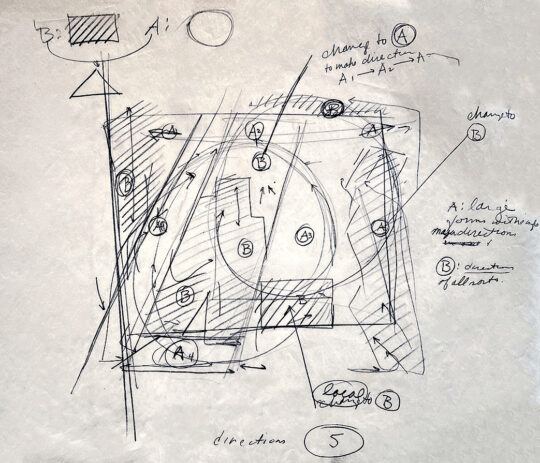

Developmental Stages of the Final Triptych

As you compare each of these studies, note how Gulamerian made changes in refining it, from the conceptual drawings in 1997 to its completion in 2014.

The Passion Series

-

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Final Passion Triptych, 2014

76 x 180.5 inches (193.04 x 458.47 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnderpainting of central canvas, en grisaille brunaille , ca.2005

76 x 84.5 inches (193.04 x 214.63 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe finished central panel of the final triptych, 2014

76 x 84.5 inches (193.04 x 214.63 cm) -

DETAILS

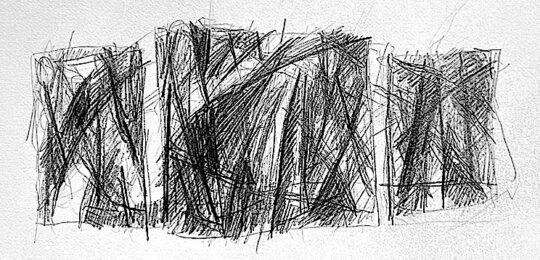

DETAILSAbstract motion study for the 2nd triptych, 1991

5 x 8 inches (12.7 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract motion study for the 2nd triptych, 1991

12 x 12 inches (30.48 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract motion study for the final triptych, 1999

4 x 9 inches (10.16 x 22.86 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe second Passion triptych, 1990-98

72 x 174 inches (182.88 x 441.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSChrist and the Veil of Veronica, 1997

23.5 x 29 inches (59.69 x 73.66 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for the final triptch, 1997

23.25 x 29 inches (59.06 x 73.66 cm) -

DETAILS

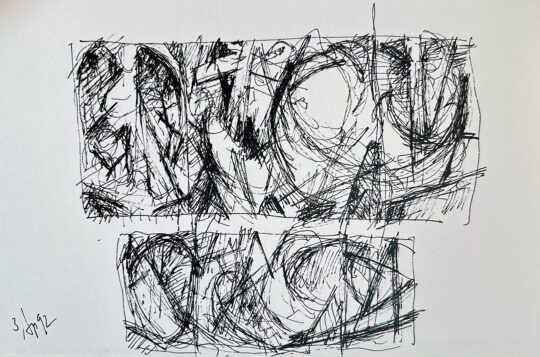

DETAILSStructural organization study, 1992

9.25 x 14.5 inches (23.5 x 36.83 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStructural organization study of triptych, 1992

7.5 x 9.5 inches (19.05 x 24.13 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStructural organization study of triptych, 1991

12 x 12 inches (30.48 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

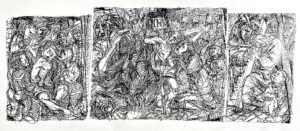

DETAILSThe first Passion triptych, 1975–81

60 x 134 inches (152.4 x 340.36 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for the central canvas in the 2nd Passion triptych, 1991

12 x 12 inches (30.48 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSA backstage Pieta, 1987

15 x 18 inches (38.1 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSHead of Christ, 1984

11 x 14 inches (27.94 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Crucifixion, 1984–90

72 x 84 inches (182.88 x 213.36 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for Crucifixion, 1984

23 x 29 inches (58.42 x 73.66 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for Deposition, 1983

23 x 29 inches (58.42 x 73.66 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Small Crucifixion, 1981–88

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCast party, 1980

20 x 30 inches (50.8 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBirth and Crucifixion, 1978

22 x 30 inches (55.88 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Mocking, 1971

43 x 40 inches (109.22 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Deposiion (en brunaille), 1969

40 x 48 inches (101.6 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Crucifixion, 1968–70

55 x 60 inches (139.7 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDirectionals for movement in a painting, ca.1967

17 x 14 inches (43.18 x 35.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Deposition, 1968–72

60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114.3 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Crucifixion, 1964

23 x 30 inches (58.42 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for Crucifixion, 1966

9 x 12 inches (22.86 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Crucifixion, 1964

30 x 36 inches (76.2 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Tambourine Player, 1961

21 x 16 inches (53.34 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Young Carnival Singer, 1968

39 x 44.5 inches (99.06 x 113.03 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAftermath, The Players, ca.1960

52 x 52 inches (132.08 x 132.08 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEcce Homo, 1950s

55 x 39 inches (139.7 x 99.06 cm) -

DETAILS

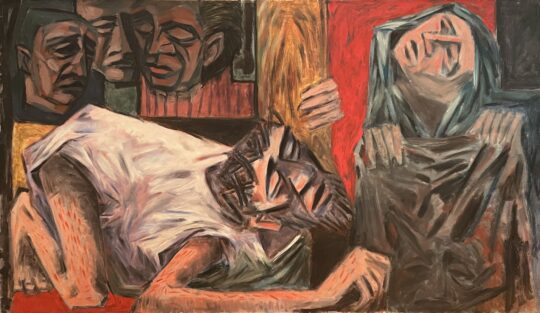

DETAILSThe Deposition, ca.1955

60 x 39 inches (152.4 x 99.06 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Flagellation, 1950s

36 x 36 inches (91.44 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Deposition, 1950s

38 x 42 inches (96.52 x 106.68 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Horn Player, 1953

12 x 24 inches (30.48 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Crucifixion, 1950s

28 x 23 inches (71.12 x 58.42 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCarrying the Cross (and Veronica), 1950s

28 x 48 inches (71.12 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract Crucifixion — Being Hung, 1950s

17 x 22 inches (43.18 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAbstract Crucifixion, 1950s

20 x 30 inches (50.8 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEcce Homo — The Carnival, 1952

52 x 62 inches (132.08 x 157.48 cm) -

DETAILS

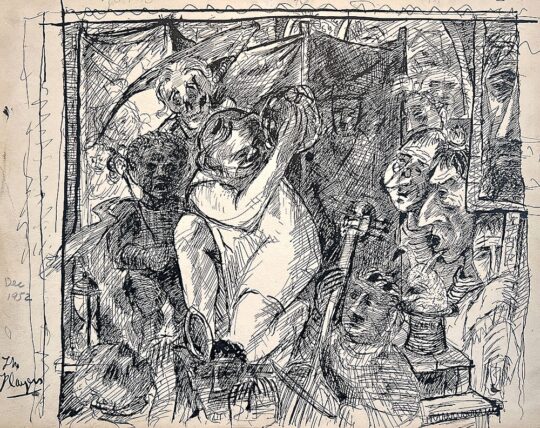

DETAILSThe Players, 1952

11 x 13.75 inches (27.94 x 34.93 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Pieta, 1952

62 x 52 inches (157.48 x 132.08 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Mocking, ca.1952

25 x 35 inches (63.5 x 88.9 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWearing the Holy Robe, 1952

48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

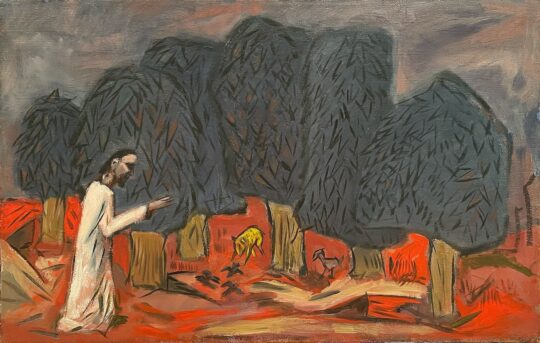

DETAILSChrist in the Grove, ca.1952

14 x 22 inches (35.56 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

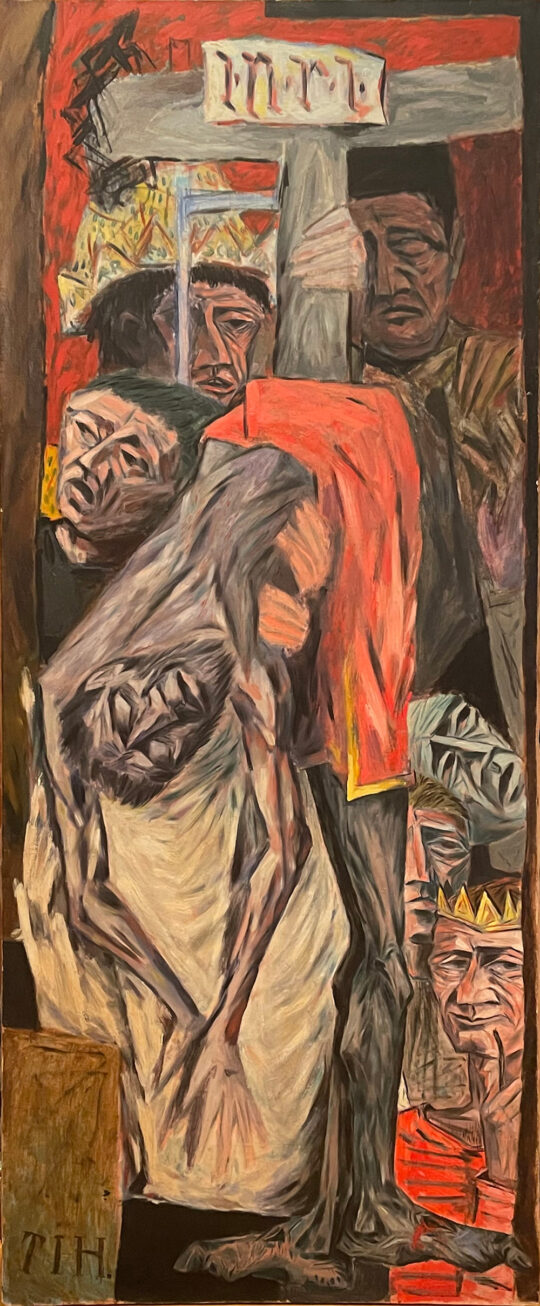

DETAILSThe Deposition, 1951

69 x 28 inches (175.26 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCasting Lots, ca.1951

51 x 17 inches (129.54 x 43.18 cm)