The Freedom of Color

Art is the world egg,

the shamanistic fruit

from which is born

the images that make history

— Beverly Brodsky, “The Message”

(based on a dream from the late 1970s)

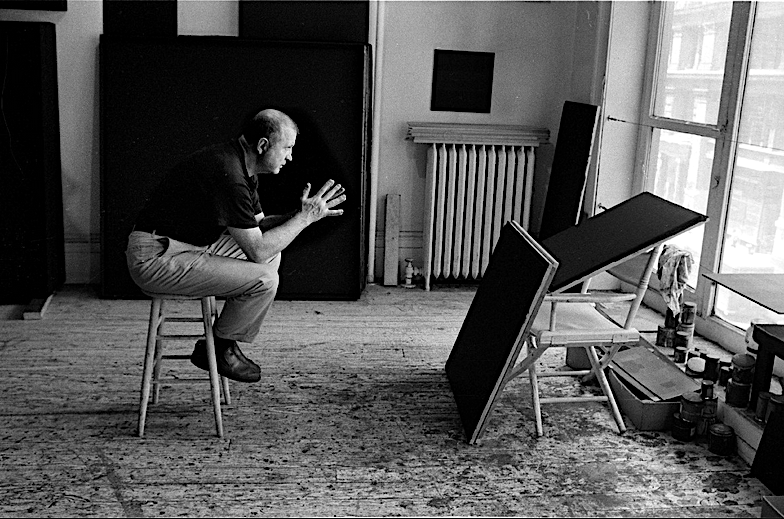

Brodsky’s first classroom experience under Ad Reinhardt at Brooklyn College in 1961 was an extraordinary one. The students were asked to take their places in front of their easels in the large studio. The master had set up each easel with a 30 x 40-inch canvas primed white. As if the sight of the archetypal blank canvas was not intimidating enough, he spoke only once, issuing the simple directive: “Begin.” Then, with no explanation, he quickly departed the studio full of surprised students. When Reinhardt returned a few hours later, he slowly paced by the easels, reviewing the paintings in progress, but rarely speaking. When he came to Brodsky’s painting he paused and asked, “Who taught you how to paint?” Brodsky struggled to find a reply when Reinhardt answered his own question, saying, “You must have known all along.”

Reinhardt later imposed a time-honored assignment with which generations of students have predictably struggled — the self-portrait. However, he complicated the task by limiting his students to only a very hard 6H graphite pencil on 30 x 22-inch paper. Moreover, the assignment was to last for the entire semester. That duration demanded constant looking in the mirror at one’s self, and the inevitable introspection elicited by such focus. Halfway through the semester half of the students had quit the class. In the final week, only Brodsky and another young woman remained. The final review was brief. Brodsky’s colleague was first to approach Reinhardt with her drawing. Standing before him, she tore her drawing into pieces and tossed them up in the air. As she turned and left the studio Reinhardt simply laughed.

“Reinhardt constantly taught commitment,” says Brodsky. “He never used the word but that’s what he taught, not technique.” Upon graduation in 1965 Brodsky was awarded best in her class.

Becoming a Colorist

Brodsky was the daughter of parents who had escaped the pogroms, cholera, depression and famine that swept Eastern Europe in the wake of WWI. In 1920 they immigrated to New York and settled in the Lower East Side. They eventually moved to a small three-room apartment in a Brooklyn tenement building where their daughter was born in 1941. Brodsky’s mother imbued her with a passion for all the arts, and regularly brought her to New York’s art museums. They especially loved performances of ballet, opera, and classical music.

These parallel passions for music and art were reinforced throughout Brodsky’s childhood. One of her most memorable childhood experiences as a little girl was one that bolstered her conviction that she was a colorist. On her regular walk by the local drugstore owner’s building, she was always curious about what she called the secret garden, always hidden from sight by a tall fence. One day the fence door had been left open. As she dared to venture just inside for the first time, the explosive sprays of colors emanating from so many different blooming flowers surprised her. She was ecstatic, discovering that color could provide such a deeply emotional sense of delight and revelation of freedom.

During high school Brodsky focused on art and music — indeed, for twenty years she was a dedicated pianist. At fourteen she began taking regular classes in life drawing at the Brooklyn Museum Art School (now a part of the Pratt Institute). In 1959 she entered Brooklyn College, studying under Ad Reinhardt, Burgoyne Diller, and Robert Henry. Further inspiration came from a trip to Mexico City In 1961 where she studied the colorful monumental murals of Diego Rivera and Jose Orozco. That year she also found new freedom upon renting her first studio, on the Lower East Side, where she not only painted many canvases but also painted the doors and walls. Her mentor, Ad Reinhardt, visited her studio and encouraged the boldness of her approach to painting. She would have another similar vivid experience of freedom when she first saw de Kooning’s paintings at a solo exhibition at Sidney Janis Gallery in 1962. It mattered little to her that the show was panned by critics as the end of Abstract Expressionism. Within months Janis rebounded with the seminal New Realists exhibition, which announced the arrival of Pop Art. But for Brodsky, de Kooning’s work was “the epitome of freedom of motion — just like ballet,” she recalled, “You can’t escape de Kooning’s innovation.”

Also in 1962, while still in college, Brodsky landed a job at Herbert Mayer’s World House Galleries. The gallery had become the most prominent on Madison Avenue, designed by the renowned architect-artist-theater designer Frederick John Kiesler who had installed an impressive spiral staircase leading to its second level. The gallery represented an eclectic group of European artists such as Herbert Bayer, Bernard Buffet, Jean Dubuffet, Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, and Giorgio Morandi. For the next two years Brodsky also came to know two of the gallery’s leading Abstract Expressionists — Esteban Vicente and Philip Guston. When the gallery’s director learned that her assistant was an artist, she asked to see her work. She was so impressed that she added Brodsky’s watercolors to an exhibition to hang beside abstract watercolors by Kandinsky and Klee.1 Brodsky’s pattern of being a working student continued when she became an assistant designer under the director of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts & Design).

Brodsky graduated from Brooklyn College in 1965 and at the ceremony received the honor award in painting as best in her class. She saw Reinhardt again in 1966 at the opening of his celebrated retrospective exhibition at The Jewish Museum. For the next three years she taught art to children at P.S. 257 in Brooklyn, and was impressed by the freedom and exuberance in the children’s works. However, in her previous stint at the Museum of Arts & Design she met the pioneer fiber artist Lenore Tawney [1907–2007] and had remained so “mesmerized by Tawney’s dynamic and complicated woven forms” that she entered the School of Visual Art to study textile design. Shortly after graduating in 1969 she married a filmmaker. They traveled to Greece, viewing the ancient frescos and temples and witnessing the ongoing excavations on the islands of Santorini (Thera) and nearby Crete. This trip inspired her to begin painting with heavier impasto and, like an archeologist, experiment with pentimenti — the revelation of traces of earlier layers. Her husband’s work next brought them to France’s Cote d’Azur where from 1970–1972 she began to paint large-scale oils on canvas dominated by light and color, which were exhibited at the La Napoule Art Foundation, west of Cannes on the French Riviera. Brodsky’s thirst to directly examine paintings by the European masters led to extensive travel, from Henri Matisse’s cathedral in St. Paul de Vence to Picasso’s ceramic studio in Vallauris. Traveling north, she visited Claude Monet’s Gardens at Giverny and then to Amsterdam to see the Vincent Van Gogh collection as well as Rembrandt, “whose glazes and genius for portraying light captivated me.” This pilgrimage continued to the Prado in Madrid where she was fascinated by Goya’s powerful romantic images such as Saturn Devouring his Son, which she found “utterly primal.”

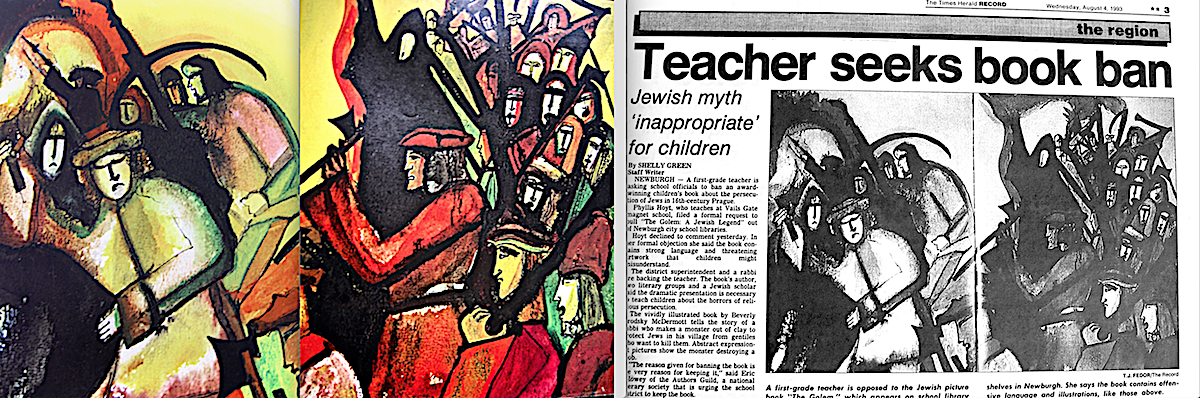

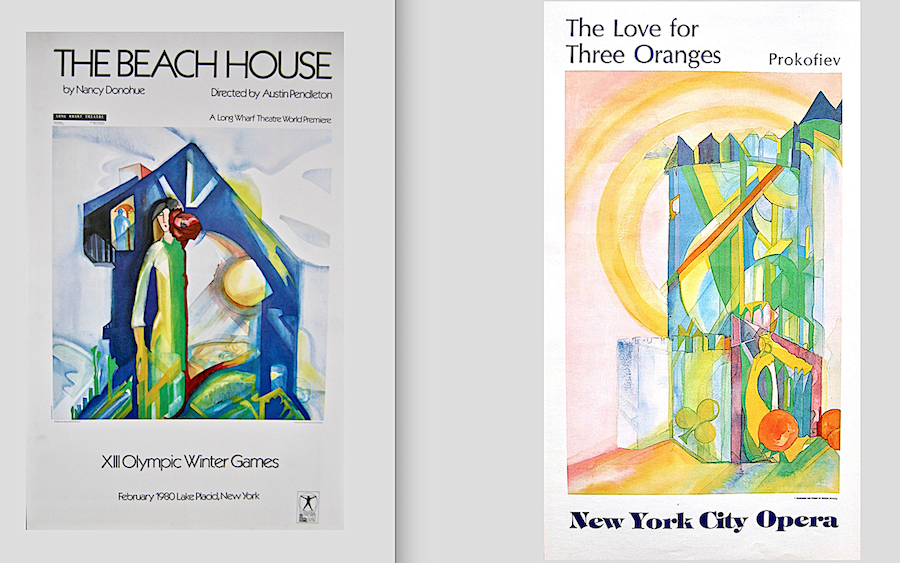

Embarking upon Double Lives

Although Brodsky’s earlier inspiration from Lenore Tawney had tempted her to pursue textile design, her travels in Europe and her joy with larger canvases reconfirmed that she was a painter — a direct descendent of the Abstract Expressionists. However, the necessity of earning a living drew her into embarking upon double lives. After returning in 1973 she settled in Washington Depot, Connecticut. There she turned to a profession where her skills as a colorist and designer would prove useful: children’s book illustration. Her first books were well-researched mythological and folkloric themes. At the same time she continued to pursue her abstract painting — which ran parallel with book illustration for the next thirty years. For example, in 1975 she gave her first lecture on “The Language of Imagery” — about the combination of her illustrated works and her abstract canvases — at the University of California, Berkeley, and a few years later would give that lecture again at Harvard University. At the same time, she was writing and illustrating a children’s book — The Golem (1976) — that would become the most successful of her eleven books. This legend of Jewish mysticism (the Kabbalah) had first appeared as a German silent horror film in 1915. While living in France Brodsky had seen the original film on television and found its spatial distortions and dark sets haunting. The Golem was praised in The New York Times Book Review: “Words can only suggest how different [this book] is from the kind of kiddie-Kitsch celebrated by critics and prize committees during an average publishing season…Brodsky is resolutely mystical, just the kind of holy terror who can make herself at home with spiritus mundi and the miraculous.”2 The Golem won the Honor Caldecott Medal in 1977. Later, Brodsky even collaborated with a theater group for the performance of “The Golem,” at the M.I.T. Center for Advanced Visual Studies. The director of the Pilobolus Dance Theater and Phoenix Dance Theater was also so attracted to her imagery that he commissioned her to create stage set paintings for his companies’ performances. Surprisingly, despite having been reprinted many times, in 1993 The Golem was censored by the elementary school libraries in Newburgh, New York, after a first-grade teacher complained that its images of religious persecution under the pogroms were too “threatening.”3 After a year-long legal battle The Golem defeated anti-Semitism and won its permanent place on those bookshelves.

The director of the Authors Guild helped to return The Golem to the library shelves in this reprisal: “Society faces a seemingly intractable problem of hatred and anti-Semitism, and New York schoolchildren are not insulated from it…The appropriate way to deal with this and other acts of bigotry is not to hide them from children but rather to bring to light the myths and slurs that form the basis of the hatred. A classroom or library discussion of The Golem could not only inoculate children against the falsehoods of anti-Semitic speech but also could start tomorrow’s leaders thinking about how to solve one of Society’s more pressing problems.”

In many ways, Brodsky’s research into mythology and symbolism for The Golem proved a powerful and enduring catalyst for the development of her paintings. Its mysticism joined with numerology, alchemy — and the primal mark-making of non-literate cultures as found in cave paintings — to become part of a vocabulary that has continuously flowed into her paintings. In 1980 Brodsky rediscovered that “teaching opened up a new way to interpret and demonstrate art” when she joined the staff at Parsons School of Design (a part of The New School). Amazingly, for the next five years she managed to also juggle teaching at Cooper Union and Adelphi University. She has remained at Parsons teaching painting and color theory.

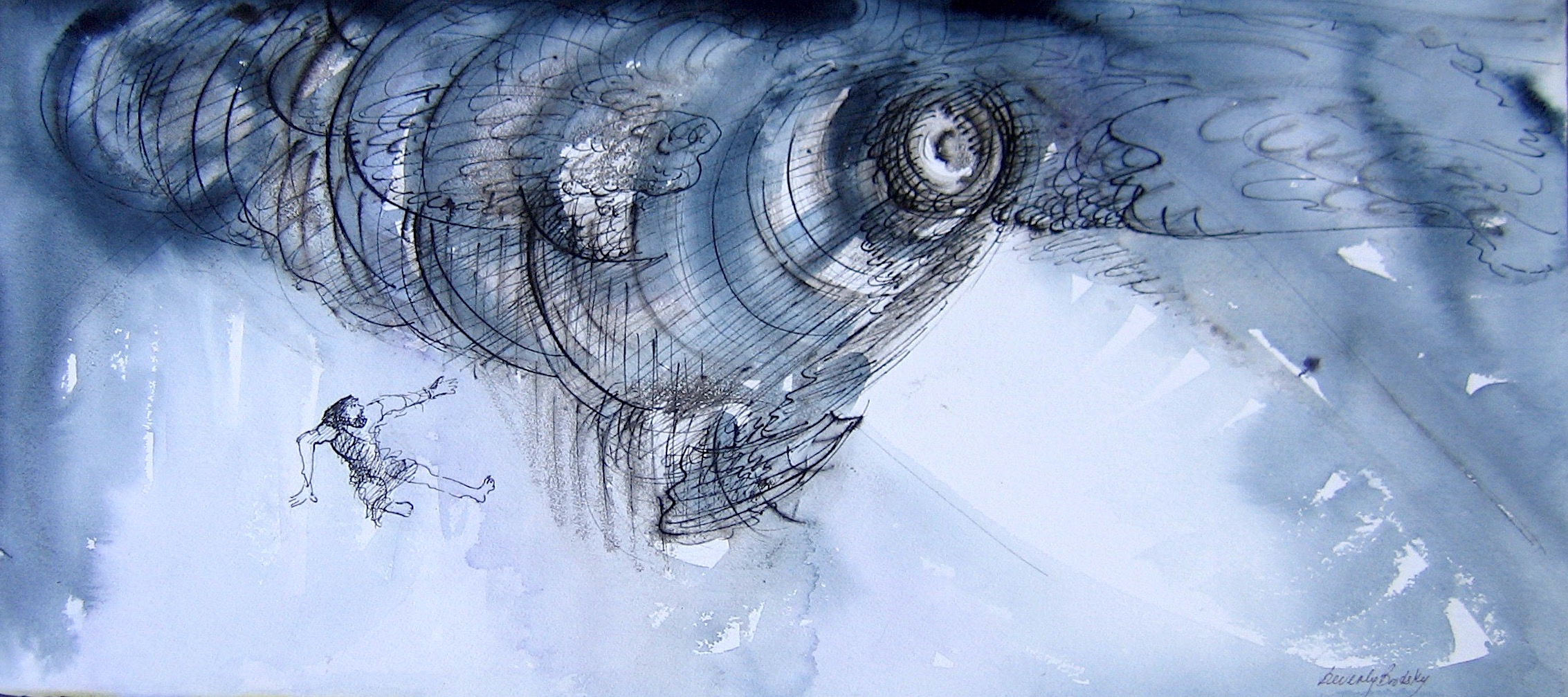

“These pictures are something like Tiepolo on LSD”

In 1986 George Braziller published another of Brodsky’s successful books, The Story of Job: The Old Testament — which was largely for adult audiences. A reviewer for The Washington Post wrote, “These pictures are something like Tiepolo on LSD — a visual equivalent of the strong emotions of Job.”4 Elaine de Kooning, whose collage workshop Brodsky had joined in the early 1980s, took notice of Brodsky’s double life and wrote, “I’m impressed by the intensity of your imagery. Also impressed by the long list of your other accomplishments — the books, the posters, the film strips, the lecture — all indications of a magnificent energy level… I’ll be seeing your show at Parsons this Wed., Sept. 24”5

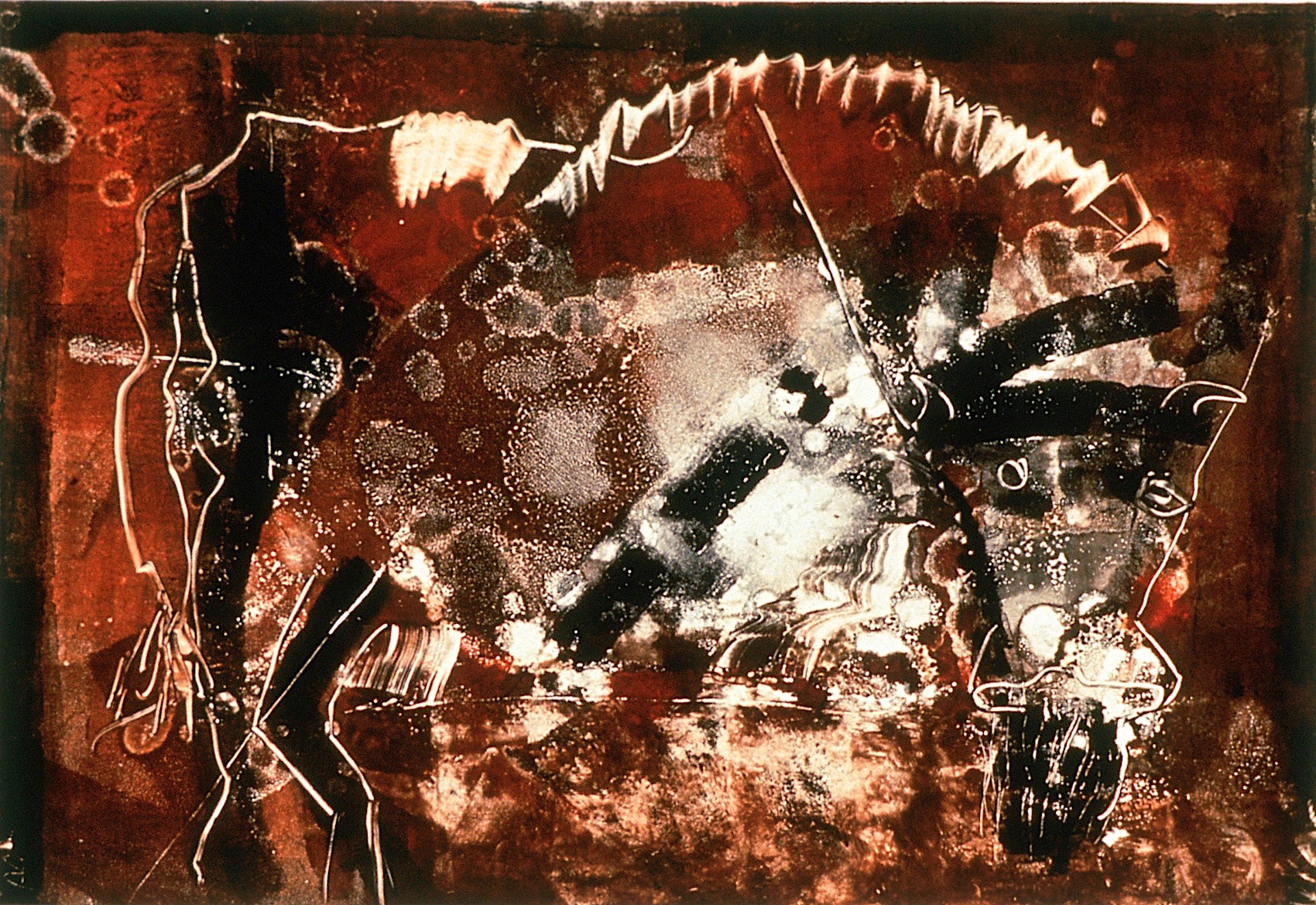

In 1988 Brodsky found another level of inspiration in her approach to painting when she was awarded a residency at the Triangle Artists’ Workshop at the Mashomack Preserve in Pine Plains, New York. Founded in 1982 by the sculptor Anthony Caro, the focus of the workshop was on the process of making work rather than the end product. This would be the first time Brodsky had the advantage of a huge studio space in a barn — along with large supplies of paint, brushes, and huge rolls of canvas. It was just the catalyst she needed for producing much larger canvases. She grabbed a 6-foot wide roll of canvas, unrolled 14 feet of it, and dove into the greater freedom of movement afforded by the monumental format. Circling about the canvas, she became an action painter — splashing, splattering, and spilling oil pigments thinned with turpentine. One of her most successful paintings from the residency was Excavations. Inspired by her having viewed the excavations in Santorini, she created a textured surface whose layers appeared ancient. The sand and various found objects reinforced this feeling, including the feathers and straw that were embedded into the thick pigments. Then, using several palette knives, she pushed and dragged the pigments as well as etched sgraffito marks into the layered surface.

The Freedom of Intuition

Indeed, freedom is a recurrent theme in Brodsky’s career, appearing as a series of revelations: the freedom of color discovered in the secret flower garden of her childhood, the freedom of resolute independence found in her first studio-apartment in 1961; the freedom of motion revealed in her schoolchildren’s paintings in the 1960s — as well as those of de Kooning; and, the freedom of painting her first large scale canvases the early 1970s in the south of France. However, Brodsky cautions her students that the freedom that appears inherent in Abstract Expressionism too often tempts painters to take many directions, resulting in forms that fail to overlap effectively or colors that lose their purpose. “Ultimately, I want to engage viewers in a visceral way through the materiality of paint,” she says, “With an intuitive approach, I hope to allow the viewer to slowly discover my abstract world. Within each labor-intensive painting, is an essential universe, materialized with dynamic, organic forms. Masses of elements (steam, fire water, wind and earth), and fragments of time often shift and collide. When they emerge, they are painted through and resolved.”

The Triangle residency culminated with an exhibition for which the visiting critics, Karen Wilken and Clement Greenberg, selected Brodsky’s Excavations for commendation. Greenberg lingered over Excavations for a long time before suddenly exclaiming with praise, “Oh my God, there’s stuff in your work!”

In 1990 Brodsky was a resident in Monchengladbach, Germany, where her works on paper were exhibited in several galleries. Juni Magazin Fur Kultur & Politik also published her abstract paintings in a special edition, Eighteen From New York (1991).

In 1991, Brodsky traveled to Japan to visit the Buddhist shrines and sacred places. “I had always been an admirer of Japanese painting. Spiritual ideals relating to the universal striving for enlightenment became an important theme in my life and work,” she explained. “When I returned home I filled my abstractions with glazes, evoking the mist and steam of hot springs and volcanic landscapes, rich with ochers and greens.” Returning to Japan for a month in 2003, she exhibited her paintings at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Obihiro.

Even as a student, when she was absorbing the works of the Abstract Expressionists, she was also discovering the freedom of motion in Chinese and Japanese painting. “Through my study of the principles of Zen I came to appreciate the void — the quintessential creative energy of the world.” The titles of her paintings often include words like ocean, river, cove, marsh, bayou, and mangroves — asking us to become immersed in the beauty of nature’s unspoiled water environment. Her orchestration of color, shapes, and brushwork invites meditation. Again, hints are found in her titles, with mystical qualifiers such as incantation, sacred stone, and artifacts — and, of course, flower. She explained that River of Fire was inspired by looking at the clear sky over the Hudson River at 3:00 in the morning and seeing a “falling star” illuminating space while reflecting upon the water. The terrible beating scene in the film, “Twelve Years A Slave” inspired Immortal. Her mother died at the same time Hurricane Sandy was ravaging lower Manhattan, inspiring her to paint Elegy.

Brodsky’s preparation for painting also reflects the discipline of an accomplished pianist. Approaching her canvases as if she were tuning her piano, she first joins the wooden stretcher bars, which are always rectangular and typically from five to seven feet in height or width. She then stretches the canvas taut, repeatedly tapping it to assure its vibrations emit a sensual tone that assures her she can begin to apply the first of several layers of gesso. The hallmark of her paintings is the chromatic tensions and transitions rippling across the surface as they evoke depth and space. This is accomplished through a careful technique using a variety of brushes, vivid high-quality pigments, and oil emulsifiers. The fine art of layering, glazing, and revealing pentimenti are crucial to her technique.

Over the decades, Brodsky’s deeply emotional response to color became her bedrock. “The final choices for my colors are mixed in separate jars with the intention of keeping my colors clean and vibrant. Pigments are applied directly onto my canvases with a variety of brush strokes. Pentimenti, reflecting worn surfaces, emerge during the process. This direct approach ensures immediacy, and ultimately the found forms. Each applied layer of paint needs time to dry into a bright, clean glaze. Since glazing creates depth I find it important to be extremely patient. I do not use drying agents as it changes the chemistry of the pigments. During the waiting period of up to three or four days, I am busy creating smaller mixed-media works on paper. These include collages, monotypes, watercolors, and charcoal drawings.”

Another milestone was reached in 1997 when, after a ten-year wait, Brodsky finally moved into Westbeth in Greenwich Village — the world’s largest residence for artists. (She had been accepted upon recommendations from one of her publishers, George Braziller, the gallerist Grace Borgenicht, and the artist Chuck Close but had to wait until a studio became free.) The eleven-foot ceilings of her new studio meant that she could again create large-scale paintings. Accordingly, she called her first experiments in the new space the Scroll Series and she developed a new language in charcoals and pastels on 10-foot paper. She ultimately translated these images into her large oils on canvas. Just a year later she held the first of many exhibitions of her paintings at the Westbeth Gallery and she subsequently curated two large group exhibitions.

In 2010 Brodsky was given a ten-year retrospective at Westbeth Gallery called “Painted Through” and two years later she was awarded a grant from the Gottlieb Foundation. Ultimately, the artist’s own words most accurately describe her spirit and purpose:

“My work is a choreography of the unique physical forms in nature, and an expression of the ephemeral and transformative energy in the universe. I visualize a dynamic presence that imprints its language on all its surfaces. When I layer the paint, I think about beginnings, of primordial worlds, and about the way nature carves the earth’s crust or core to create form. My paintings, therefore, reflect the passage of geological time. They are also concerned with mysterious, non-linear realities of the spirit world and my own dream world where memories of ancient origins incubate and eventually emerge. Thus, volcanic eruptions, bursting particle-filled clouds, shifting strata, mysterious creatures, and fossilized objects are the excavated images of my canvases.

Most recently, I have been painting my abstract perceptions of the Hudson River where I live and work. My long walks there move me to new levels of sensory experiences. I am deeply affected by evolution and capacity for renewal (especially after the tragedy of 9/11), and storm Sandy, and the fact that birds and fish are returning to cleaner waters. This experience has made me even more aware of the nature of water’s, rhythm, color and light, and all the changes that occur throughout the day and through the seasons. Through my window, I am able to watch the changes in weather patterns, as well as the many varieties of clouds moving across the sky. The sunsets’ colorful abstractions take my breath away, too. And, lightning, signaling the coming of a storm, stirs me. All these natural elements influence my work. Nature is a voice that translates into form and color on my canvases.”

Think back to Brodsky as the child experiencing a deep emotional response to the colors she discovered in the “secret garden” — and later experiencing in de Kooning’s painting the vivid experience of freedom of motion. Throughout the history of painting, innovative vision has always emerged from a spiritual response to such experiences. The result has always been an urge to express those experiences in a tangible physical way through mark-making and color — from prehistoric cave paintings to the Renaissance, and to the plethora of isms that have defined the modern era. Certainly, Brodsky has not been alone as an artist appreciating the pureness of vision in children. And she’s not alone in knowing that all of those children who aspire to become artists will inevitably be influenced by the preceding generations. Naturally, the inherent innocence of the artist’s early visceral metaphysical responses would later become conditioned with exposure to the works of the most creative artists in history. The problem is that many artists who have made life-long commitments to painting have later suffered the depressing reality check from critics and art historians that their work is slavishly derivative. Failure comes when, after that exhaustive absorption of imagery, an artist can only create a series of clearly derivative, and therefore spiritually lifeless, paintings. It’s a path that many dedicated artists have unwittingly followed in earnest for their entire lives. Growing up in the second generation of the Abstract Expressionists, Brodsky acknowledges her debt to the famous figures of the first generation of the New York School whose works she admired — such as de Kooning, Gorky, Frankenthaler, and Rothko. Yet what has fostered her genuine innovation of expression is a heightened awareness for form and color that cannot be contrived or forced. At the same time, true authenticity of innovation requires a vital symbiosis, one that depends upon the several resources: that original childlike approach to seeing, a self-awareness of one’s passion and philosophy, an understanding of art history, and the technical skills to make the work sing. This is where Brodsky has succeeded brilliantly.

Inspiration certainly comes from an awareness of art history but the next level requires one to be highly conditioned to remaining true to one’s inner — or spiritual — response to nature. Every day her vision is acutely tuned to perceiving nature’s moods and colors with the same wonder she experienced in childhood. In short, her finished paintings are lyrical translations of those senses on canvas — and we come even closer to the urge to live with them when we understand the vital footing of inspiration, preparation, and technique from which they have sprung. Perhaps this attention to melodic sequences is what happens when one is trained for twenty years as a concert pianist.

— Peter Hastings Falk

FOOTNOTES

1 Herbert Mayer founded World House Galleries in 1953. He exhibited an eclectic group of contemporary artists — from masters to discoveries — from Europe and Latin America. In 1965 the gallery’s exhibition “Sculpture from all Directions” was ahead of its time, including abstract sculpture by Donald Judd, Mark Di Suvero, Tony Smith, John Chamberlain and others. After the gallery closed in 1968, Sotheby’s held two major auctions from Mayer’s private collection (in 1971 and again in 1984).

2 book review by Wallace Markfield in The New York Times Book Review (2 May 1976) about Brodsky’s The Golem, A Jewish Legend (New York: J.B. Lippincott, 1976)

3 Green, Shelly. “Teacher Seeks Book Ban” (Newburgh, NY: The Times Herald Record, 14 Aug 1993, p.3)

4 book review by Prof. Perry Nodelman, “The Magic of Picture Books” in the Washington Post (11 May 1986) about Brodsky’s The Story of Job: The Old Testament (New York: George Braziller, 1986)

5 letter to Brodsky from Elaine de Kooning, 22 Sept. 1986

-

DETAILS

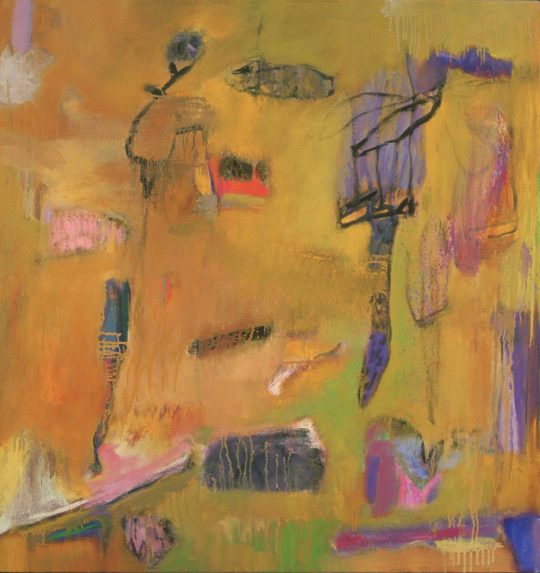

DETAILSA Floating Dream, 2003–04

68 x 72 inches (172.72 x 182.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSA Floating World, 2018–19

68 x 70 inches (172.72 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSA Violet Morning, 2006–07

68 x 68 inches (172.72 x 172.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSA Walk Through the Marsh, 2010

72 x 78 inches (182.88 x 198.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSArtifacts, 2004

52 x 56 inches (132.08 x 142.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBayou, 2001

48 x 64 inches (121.92 x 162.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlack Flower, 2009

52 x 56 inches (132.08 x 142.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlack Rose Child, 2000

40 x 38 inches (101.6 x 96.52 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlue Window, 1999

52 x 56 inches (132.08 x 142.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCascade, 2012

72 x 78 inches (182.88 x 198.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCrescendo, 2013

58 x 62 inches (147.32 x 157.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSElegy, 2012

68 x 72 inches (172.72 x 182.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEmanation, 2006

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSExcavation, 1988

81 x 62 inches (205.74 x 157.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFigure-Walking, 1997

70 x 65 inches (177.8 x 165.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGhost Dance, 2000

72 x 78 inches (182.88 x 198.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSHudson River, 2000

56 x 52 inches (142.24 x 132.08 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSImmortal, 2013

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSIn the Cove No.1, 2018

58 x 60 inches (147.32 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSIn the Cove No.2, 2018

68 x 70 inches (172.72 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSIn the Moment, 2013

42 x 44 inches (106.68 x 111.76 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSIncantation Blue, 2015

68 x 72 inches (172.72 x 182.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSIncantation Red, 2018

70 x 60 inches (177.8 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSInner Fire, 2013

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSIt Comes About, 2013

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMangroves, 1998

72 x 72 inches (182.88 x 182.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMarsh, 2003

47 x 64 inches (119.38 x 162.56 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOcean, 2004

36 x 36 inches (91.44 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPrimordial Landscape, 1998

70 x 65 inches (177.8 x 165.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPulse, 2013

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSRed Earth, 2013

68 x 70 inches (172.72 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSResurrection, 2009

72 x 78 inches (182.88 x 198.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSRiver of Fire, 2013

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStaccato, 2016

36 x 36 inches (91.44 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThrough a Vision, 2012

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTransfigured Forms, 2012

60 x 70 inches (152.4 x 177.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwilight at the River, 2011

72 x 78 inches (182.88 x 198.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhite Flower, 2000

52 x 56 inches (132.08 x 142.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWind and Sand, 1998

52 x 56 inches (132.08 x 142.24 cm)