The Importance of Art Dealer-Scholars

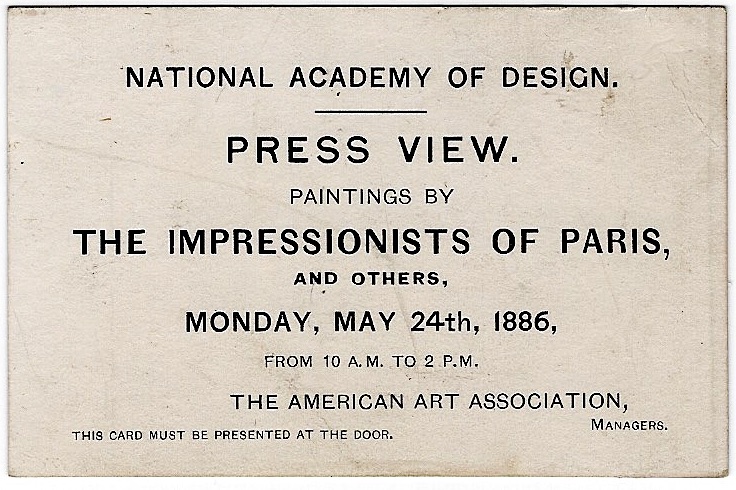

The best of art-dealing and art historical scholarship are reinforcing, not antithetical. The eye of the art dealer-scholar comes with the ability to discern true innovation that emerged from particular periods, movements, or styles. There are numerous examples of museum curators joining with gallery owners to mount significant exhibitions. Historically, the exemplar nonpareil is Paul Durand-Ruel [1831–1922] who weathered years of severe criticism and soaring debt to promote a group of painters known as the Impressionists. In 1886, after many failed exhibitions in Paris, the struggling dealer gambled by mounting a large exhibition of Impressionist paintings in New York. It opened at the American Art Galleries (both a gallery and an auction house founded just a few years earlier). The show was so popular that it continued at the National Academy of Design. It proved to be the seminal break-out moment in the market for Impressionism.

Jane Kallir, owner of Galerie St. Etienne, reminded us of the contributions of art dealer-scholars in her summer newsletter. True dealer-scholars have an insatiable desire to discover authentic innovators who may have been passed over owing to a dozen compelling reasons. The eyes and minds of art scholars — whether dealers or museum curators — are on the alert. That approach to art is why Kallir’s grandfather, Otto, was steadfast in promoting Egon Schiele despite an initially indifferent market. With his discovery of Grandma Moses he also opened our eyes to self-taught artists.

The spirit of Ms. Kallir’s newsletter coincides with the recent passing another leading dealer-scholar. Few dealers have matched the depth of research, publishing, and presentation produced by Ira Spanierman [1929–2019]. His contributions to American art scholarship were considerable — with catalogues raisonnés on the works of the American Impressionists John Twachtman, Theodore Robinson, and Willard Metcalf — as well as Winslow Homer.

Ira Spanierman was the éminence grise in the field of American Art. He was unquestionably the best-dressed dealer, and his sense of humor caught most people off-guard. Crucial to our publication, he was one of our early behind-the-scenes advisors. After all, he had excelled in the niche of discoveries and rediscoveries. He was completely undaunted if an artist lacked an impressive exhibition history or laudatory critical reviews. Instead, he trusted his eyes — his visceral perception. Then, in a nanosecond, his reaction to quality was tempered by scholarship — which meant he quickly sensed if the work exuded the requisite powerful fusion of innovation and historical significance.

As affinity partners we enjoyed working closely in curating a number of discovery exhibitions. He also understood how to create an effective symbiotic relationship with museums, one that would truly benefit the public’s appreciation of American art. He began at twenty-one as an auctioneer with his father’s Savoy Auction Galleries on 59th Street at Fifth Avenue. In 1961, he opened his own gallery specializing in 19th and early 20th century American paintings and sculpture — long before the Bicentennial became the explosive catalyst for a new art market. His staff grew to be the largest in the country.

No story about Ira Spanierman’s connoisseurship would be complete without mentioning his discovery, purchase, and eventual sale of a major Old Master painting. I recall him pointing to a shelf of books and folders, all related to a “school of” Raphael that he had purchased at auction in 1968 at Sotheby Park-Bernet. Despite the painting being very dirty and hanging high near the showroom’s ceiling, Ira’s curiosity made him find a ladder for a close-up view. A few details spoke to him, including a beautifully rendered right hand. Ira bought the painting for $325 and conducted years of exhaustive research, ultimately finding scholarly consensus on authenticity. He decided to simply enjoy living with it for the next four decades. Finally, in 2007 Ira decided to part with the painting now formally identified as Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino by Raphael. It’s clear that at age 78 he did not sell because he needed the money. He was just curious to enjoy what would happen. After someone paid more than $37,000,000 he joked in his usual deadpan manner, “Somebody got an incredible bargain.”

Ira Spanierman was a modern-day Durand-Ruel. He was a notorious micro-manager of his exhibitions — from research strategies and publishing details to the framing and lighting. As a result of his adherence to scholarship and taste his gallery stood as one of the most successful in America.

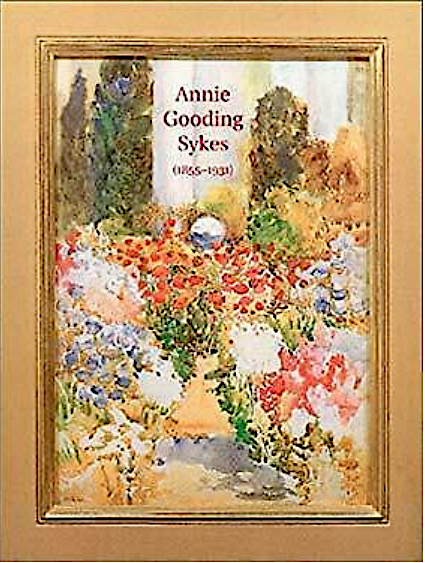

He also empathized with relatives and estate owners embarking on the arduous process of seeking representation for an artist’s collection. Many have made the rounds through galleries, hoping to be greeted with interest. Too often, persons behind the desks in white box galleries don’t even bother to find out why you’re visiting. Ira Spanierman stepped forward and was engaging. He had an insatiable curiosity to make discoveries. He closed the gallery in 2014, largely owing to health reasons and, like Durand-Ruel, passed away at 90.

We are grateful to Ira for sharing the thrill of discovery in the exploration of artists’ lives, and for inspiring us to continue serving as a catalyst for the (re)introduction of forgotten yet significant artists to the public. He reminds us that the profession of the true art dealer-scholar does not look forward to retirement.

An important part of our mission is to publish feature articles on the careers and projects of all art dealer-scholars. If we have not yet met, let’s get acquainted!