Philip Morsberger: A Passion for Painting

PREFACE

“Once seen, never forgotten” is a phrase that might be used to summarize Philip Morsberger. The intensity, energy, humor, and passion for life and art are immediately apparent. So, too, are the warmth of spirit and the capacity for friendship, which have been exercised on both sides of the Atlantic for many years.

Curiosity and restlessness have kept Morsberger on the move like a modern Odysseus. His art has great variety and includes realism, abstraction, and a comedic narrative vein replete with its own inventive imagery that is totally individual. During the 1960s, he engaged directly with contemporary issues, but in recent years memory has become more important, and his latest work could be described as a form of Magical Realism.

I first met Philip Morsberger in Oxford when he was Master of the Ruskin School of Drawing, where I was employed from 1968 to 1988. Even though I moved away from the Ashmolean Museum to take up the post of Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures, we have kept in touch. I am not alone in finding the art of Morsberger fascinating. The aim here is to review his oeuvre and to set it in context.

Many people have already written about Morsberger’s work in catalogs, journals, and newspapers. I have benefited enormously from the illuminating insights and pertinent observations of Kenneth Baker, Richard Gruber, Marcia Tanner, Jim Garvey, and Robert Hartman, among others. I am confident, however, that I will not be the last person to become ensnared by Morsberger’s intriguing pictures and to feel the urge to write about them.

THE ART OF PHILIP MORSBERGER: ASTRIDE THE ATLANTIC

Philip Morsberger has been a painter for more than fifty years. Moving between the USA and Britain at regular intervals, he has witnessed all the major developments that have taken place in art during those years. Yet through it all he has maintained his own distinctive outlook on the world, which has, in turn, found expression in a highly personal style of painting. Although obviously conversant with the different art movements that have come and gone during his own lifetime, Morsberger has not allowed himself to be categorized, just as he has never associated himself wholeheartedly, or for any length of time, with one particularly influential artist or group of artists.

3/8 inches

What Morsberger does have is a strong commitment to the principles that underlie his art. Equally apparent is the fact that those principles have been present from the outset and that, regardless of the variety in his paintings, Morsberger has never deviated in his pursuit of them. Allied to this is the artist’s compulsive work ethic and iron self-discipline. Wherever he has been in the USA or Britain, the studio has been the hub of all his activities. He does not carry a sketchbook, and he eschews photography. Instead, he engages directly with people and then relies on visual memory. Such an approach derives in part from Morsberger’s initial training, but it also has to do with the way he has evolved as an artist. The studio is very much a private space, used not only for the concentrated activity of making art but also for solitary musing, reading, and reflection. His inspiration comes from inside himself, as opposed to external influences.

The various studios Morsberger has occupied are invariably converted spaces that are quickly transformed in ways that hint at the monastic cell. Apart from the essential materials for painting, there is a large selection of books (Charles Dickens, Henry James, Arthur Conan Doyle, John Steinbeck, Anthony Burgess, Paul Auster, Peter Carey, or Joyce Carol Oates), a random group of photographs and postcards of works of art by admired artists (El Greco, Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec), a few personal mementoes, and two pianos — one an upright and the other a miniature — both of which are played. The appearance is spartan and hermetic. It is a private world, but one that is not totally disengaged from reality so much as a comment on it. Correspondingly, the visual language of this private world is articulated in a highly personal iconography based on the artist’s own experiences.

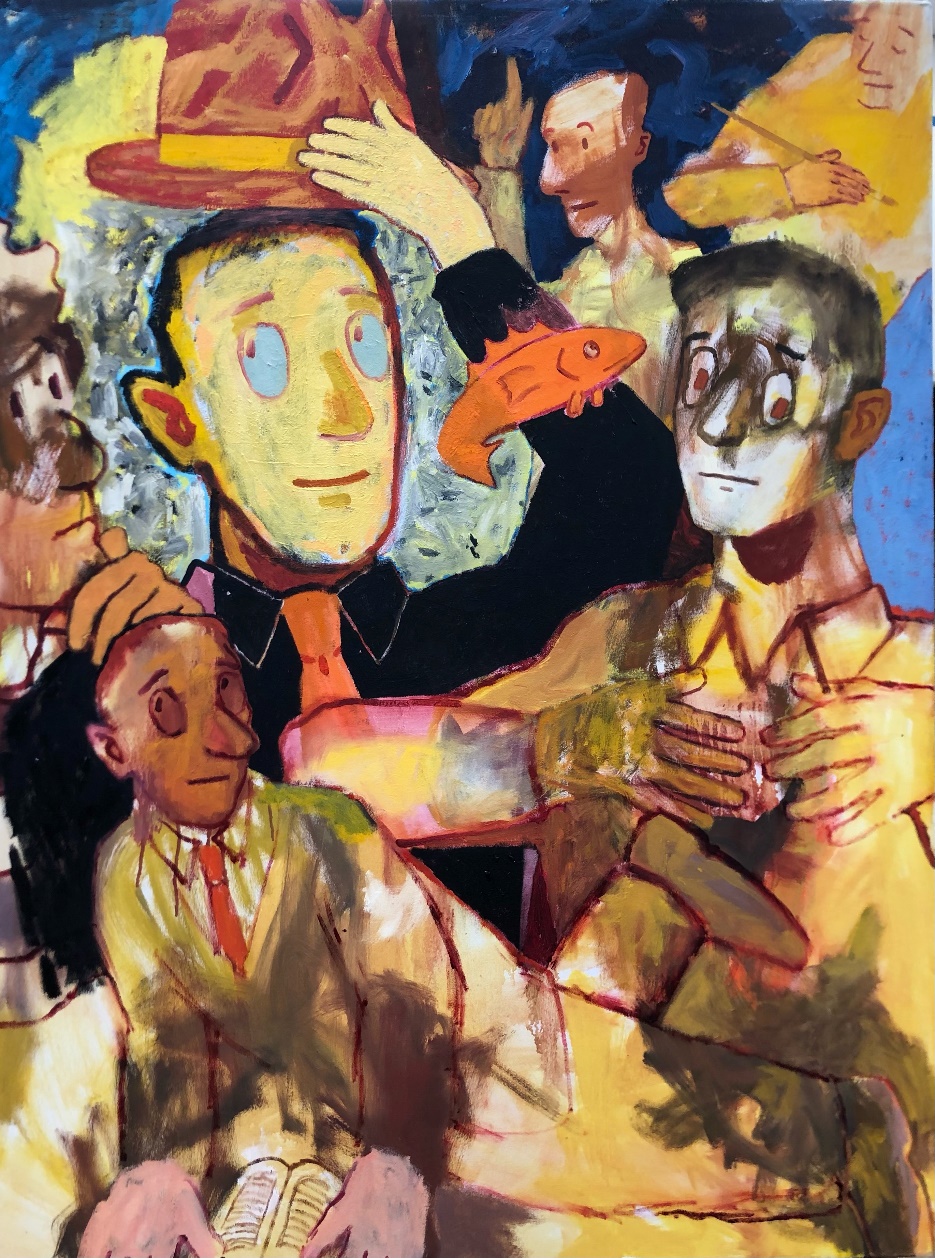

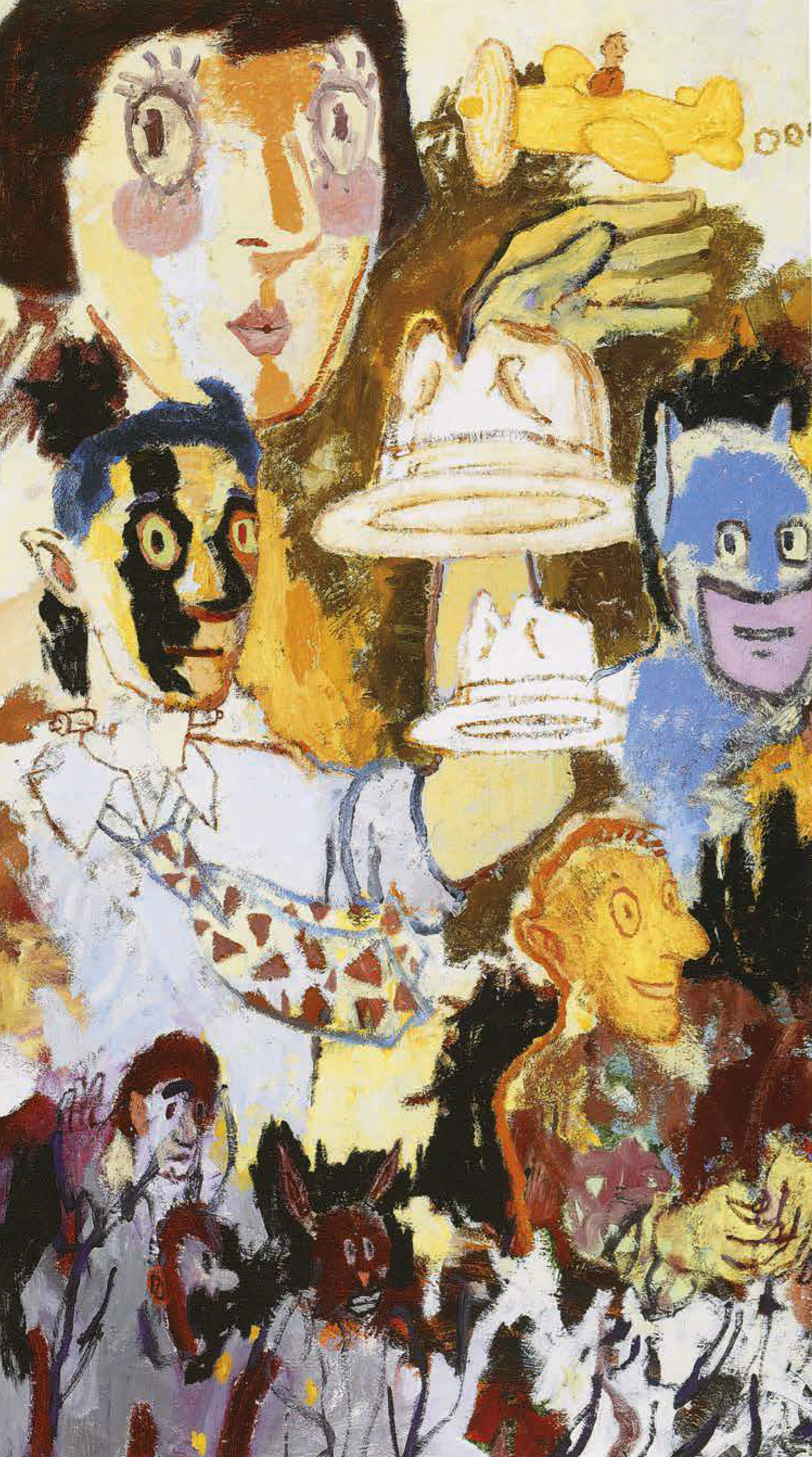

In his mature paintings Morsberger conjures up his own mythical universe, comprising a whole cast of fantastical creatures, both human and animal. The effect is like a medieval bestiary. The animals are mostly benign and friendly, as though domesticated. The humans are wide-eyed, with simplified features, leering expressions, elongated, almost disjointed, limbs, large feet with heavy boots, and pudgy hands with banana-shaped fingers. These figures are rarely still and often shown running. One writer has aptly suggested that it is always rush hour in Morsberger’s paintings.

All these creatures inhabit a turbulent, chaotic world that is hugely energized and dominated by a mood of restlessness. Everything is speeded up, as if permanently set at fast-forward, and this imparts a feeling of disjunction or even displacement. Bodies seem to float as though in a chemical experiment or as in space, often colliding before moving off in different directions. It is a prelapsarian world in free-fall — or so it would seem at first sight.

These same paintings also allow for some general observations to be made about Morsberger as an artist. Although the subject-matter is couched in highly personal terms, it has a universal application. Much of the imagery and several of the recurring motifs relate to the history of the artist’s own times. The random accumulation of symbols is frequently unified by an overall narrative that is succinctly explained by an apt title. Only during the 1960s is the subject matter overtly political, but that is in itself hardly surprising, given the dramatic history of the USA during that decade. Religion, too, is a subject that is rarely confronted straight on in Morsberger’s work, even though it is possible to argue in the broadest terms that religious principles have been an underlying factor from the start and have become more sharply defined by his conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1976.

Technical aspects are also a vital consideration. What may look like a naïve — or even faux naif style — is in fact carefully honed, being based on a firm scaffold of academic drawing and a diligently researched understanding of color. Indeed, the nurturing of orthodoxy both within himself and in others has given Morsberger the flexibility to paint in a variety of styles. Versatility and irrepressibility are two of his most obvious personal characteristics, and they are clearly evident in his art. It is the same with his playful sense of humor, which is based on a childlike innocence. However, the dividing line between despair and hope in Morsberger’s paintings is a fine one, and it is not always clear-cut. Within many of the paintings there are pertinent, even if oblique, observations on personal relationships and the state of the world — and in the artist’s mind these overlap. The predominant mood, however, is never one of total despair, or even the temptation to give in to despair. The reality is quite the opposite, since Morsberger’s purpose is to paint a commentary on la comédie humaine. His world is essentially one of optimism born of incredulity.

FAMILY LIFE

Philip Morsberger was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on March 17, 1933, the second son of Eustis and Mary Burgess Morsberger. A great deal of Morsberger’s art is grounded in his family. His maternal grandfather, for example, showed him how by drawing lines over a printed image you could completely alter its meaning. This demonstration of the transformative effect of art was a true revelation, and Morsberger identified this as the specific impulse that made him want to become an artist.

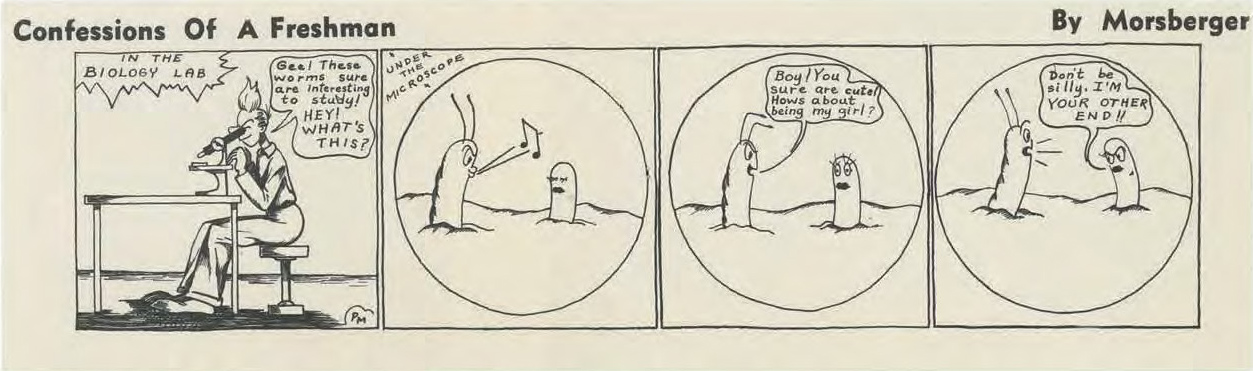

Other everyday aspects of the Morsberger household were formative. Comic strips — Little Orphan Annie, by Harold Gray, and Dick Tracy, by Chester Gould — were poured over daily by the entire family and enjoyed for their vivid characterization, ingenious storylines, and wide- ranging artistic creativity. Films, too, were important, and such performances as Charles Laughton’s Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) were relished to the point of imitation. The artist still regards many of the films he saw during his childhood as major influences.

These family ties were significant not only the formative sense; they recur in Morsberger’s art at a later day. A Long Day’s Journey, inspired by Eugene O’Neil’s play which Morsberger saw in the film version of 1962, is an example of a strictly autobiographical painting done while Morsberger’s parents were still alive.

However, during the 1980s Morsberger embarked on a number of canvases painted in a narrative style inspired by the comic strips he admired. Not only is the deliberate use of this style a clear reference to his childhood, but so too is the imagery. Eustis appears constantly, usually with one of his hats, which the artist sometimes uses as a symbol of death, suggesting the literal expunging of life, like a candle snuffer. Robert [Morsberger’s brother] is always the pilot, equipped with helmet and goggles buzzing around in the airplane. Mary does not appear often, although on occasions her features are concealed or enveloped by other figures surrounding her and emerge only after careful examination.

Although started in the 1980s and continued in the 1990s, Morsberger is still haunted by this family imagery. Family members remain in his mind as “presences” brought back to life on the canvas. These paintings adumbrate universal truths about life and death through a sequence of personal references.

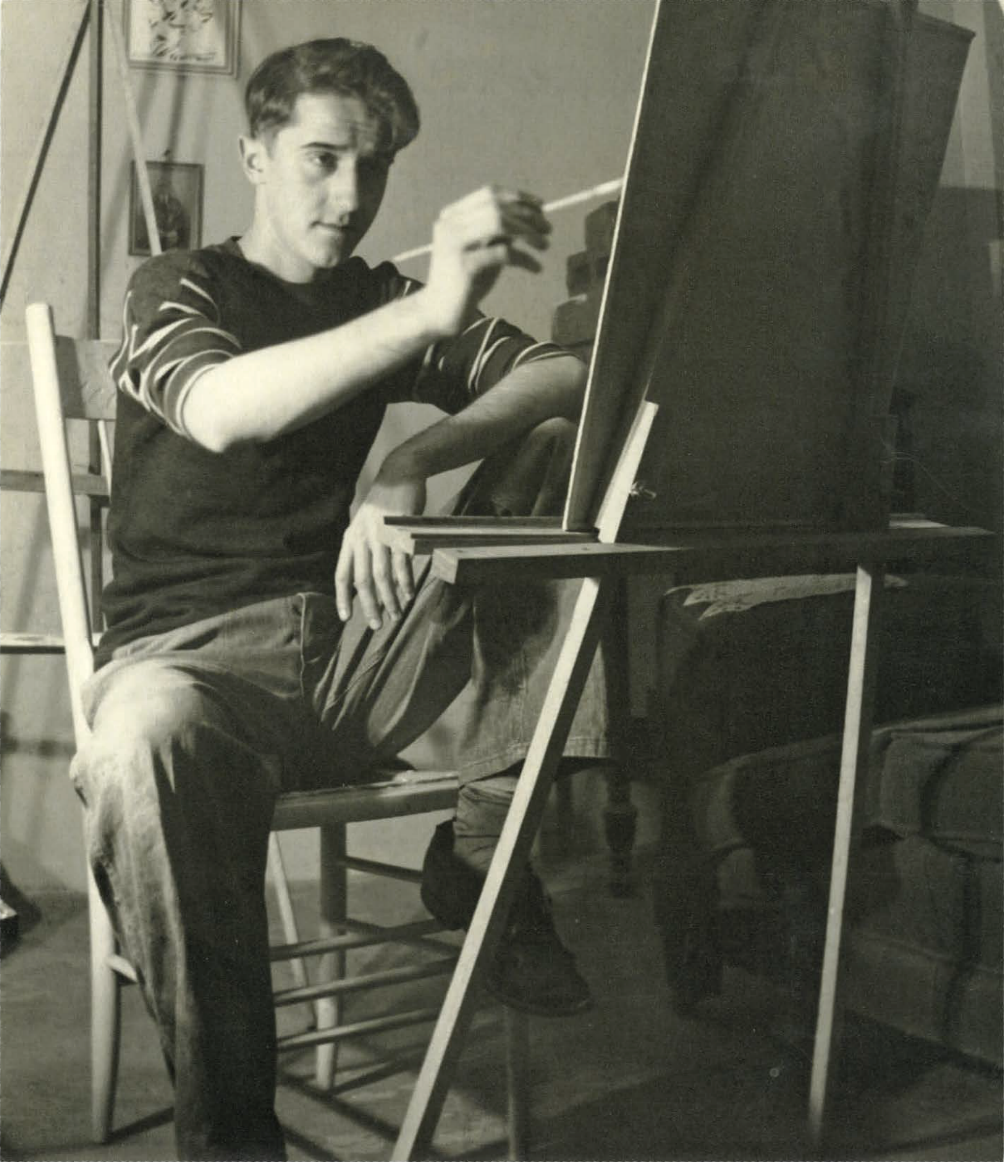

BECOMING AN ARTIST

Philip Morsberger’s rite of passage began with his attendance at schools and colleges in Baltimore. His proclivity for art had emerged early on and was acknowledged while he was at Gwynns Falls Park Junior High School, when in June 1946 he was recommended for a summer scholarship at the Maryland Institute College of Art, being described as “a very young but very talented artist” with an ability “to draw anything and everything” that is “far above the average.” Evidence of this is the rare survival of a comic strip which he drew soon thereafter for his high school.

The previous summer he had been recommended for a similar type of scholarship in music to the Peabody Conservatory of Music, indicating that his talent could have taken him in another direction. Music remains a passion, with a frequently performed and extensive repertoire on the piano, but a declaration in favor of art was followed after high school by three years initial study (1950-53) at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There he studied with Balcombe Greene, Samuel Rosenberg, and Robert Lepper, who had taught Andy Warhol. Other distinguished artists to have emerged from the Carnegie University are Philip Pearlstein and, more recently, John Currin — both figurative painters.

The Carnegie Institute of Technology exposed Morsberger to different aspects of art. The dominant style of those years was Abstract Expressionism, to which Morsberger did not personally respond at this early stage in his development. His preference was for narrative painting, and among his sources of inspiration were the figurative painters based in the Bay Area of San Francisco. He was by instinct an artist who put drawing first, and he found that he had arrived at the Carnegie Institute of Technology just at the moment when it was moving away from the traditional precepts of teaching that had originated in the nineteenth century. Sensing change, the Carnegie Institute of Technology stressed innovation, putting greater emphasis on independence of mind and action than on the more formal, structured approach usually promulgated in art schools. To a certain extent, therefore, Morsberger saw himself as contra mundum.

Detailed observation was what he sought, in opposition to an immediate reaction masquerading as modernity. Nonetheless, some of the new ideas to which he was exposed at the Carnegie Institute of Technology were stored up for use at a later stage of his development. Little did the artist realize the extent to which in future years his life would become inextricably linked with art schools both in the USA and Europe; little did he anticipate that the Carnegie Institute of Technology would be a rehearsal for future battles.

Morsberger’s time at the Carnegie Institute of Technology was interrupted by his draft in to the army in 1953. He served in the Signal Corps at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Paris. This was his introduction to Europe. Morsberger was able to explore Paris and attend night classes at the École de la Grande Chaumière. He also traveled in Italy. After being discharged he returned to the Carnegie Institute of Technology for his final year before graduating as a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1956. This accolade coincided with his marriage to Mary Ann Gallien from Fairmont, West Virginia, with whom he was in due course to have two children: Wendy (born in Oxford, England, in 1957) and Robert (born in Oxford, Ohio, in 1959).

Both the teaching at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and the introduction to Europe helped Morsberger in his development as an artist. Such opportunities enabled him to define more closely what kind of artist he aspired to be. Furthermore, they hardened his resolve to progress in a particular direction.

One of the most enlightened pieces of legislation in American history, the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act (better known as the GI Bill of Rights) was passed into law in 1944. Morsberger was himself eligible for support from the Bill of Rights. The Bill allowed for foreign placements. The prospectus for the Ruskin School offered the kind of tuition that the Carnegie Institute of Technology had moved away from, and so, having applied to Oxford and submitted his portfolio, Morsberger was accepted for admission in the fall of 1956. This is the year that marks the start of his long association with Oxford and its university.

OXFORD (ENGLAND)

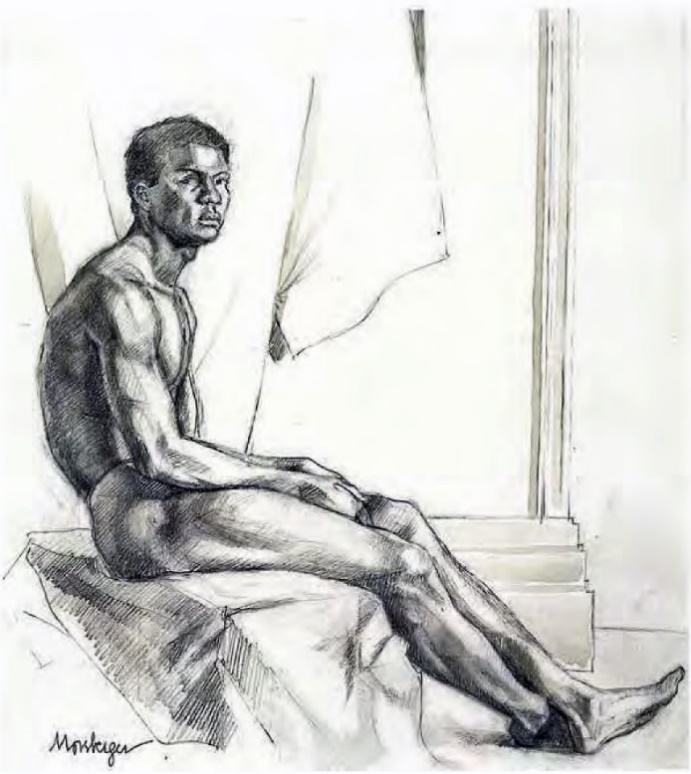

The Ruskin School in Oxford emphasized those aspects of art training that were beginning to disappear from art schools in the U.S.A. Students were expected to be proficient in making works of art from life. A fair proportion of Morsberger’ s work done while at the Ruskin School is preserved today. A group of academic studies drawn from posed models is exactly what is to be expected of work undertaken at an early stage of any artist’s development. Carefully, sometimes awkwardly, posed figures are tentatively drawn. This type of drawing is about the setting of personal standards in the long search for perfection.

The discipline acquired while at the Ruskin School has remained with Morsberger throughout his working life. Not only has he stressed its importance to those he has taught or encouraged, but in doing so he has never exempted himself from continuing the practice of drawing or painting from the model. A number of other Americans took advantage of the GI Bill of Rights to be in Oxford: the painters Elemore Morgan, R.B. Kitaj, and Neil Shevlin attended the Ruskin School.

OXFORD (OHIO)

After the Ruskin School Morsberger returned to the U.S.A., where he was appointed to the art faculty of Miami University at Oxford, Ohio — thus exchanging one Oxford for another. Morsberger taught at Miami University for nearly ten years and was occupied in a number of activities beyond teaching. He hosted a series of television programs entitled Dialogues in Art; he acted (notably as King of Siam in The King and I); and he had a close involvement with the Miami University Hiestand Gallery both as a contributor and as an administrator. But, however significant those activities may have been, it was Morsberger’s art that was his main concern.

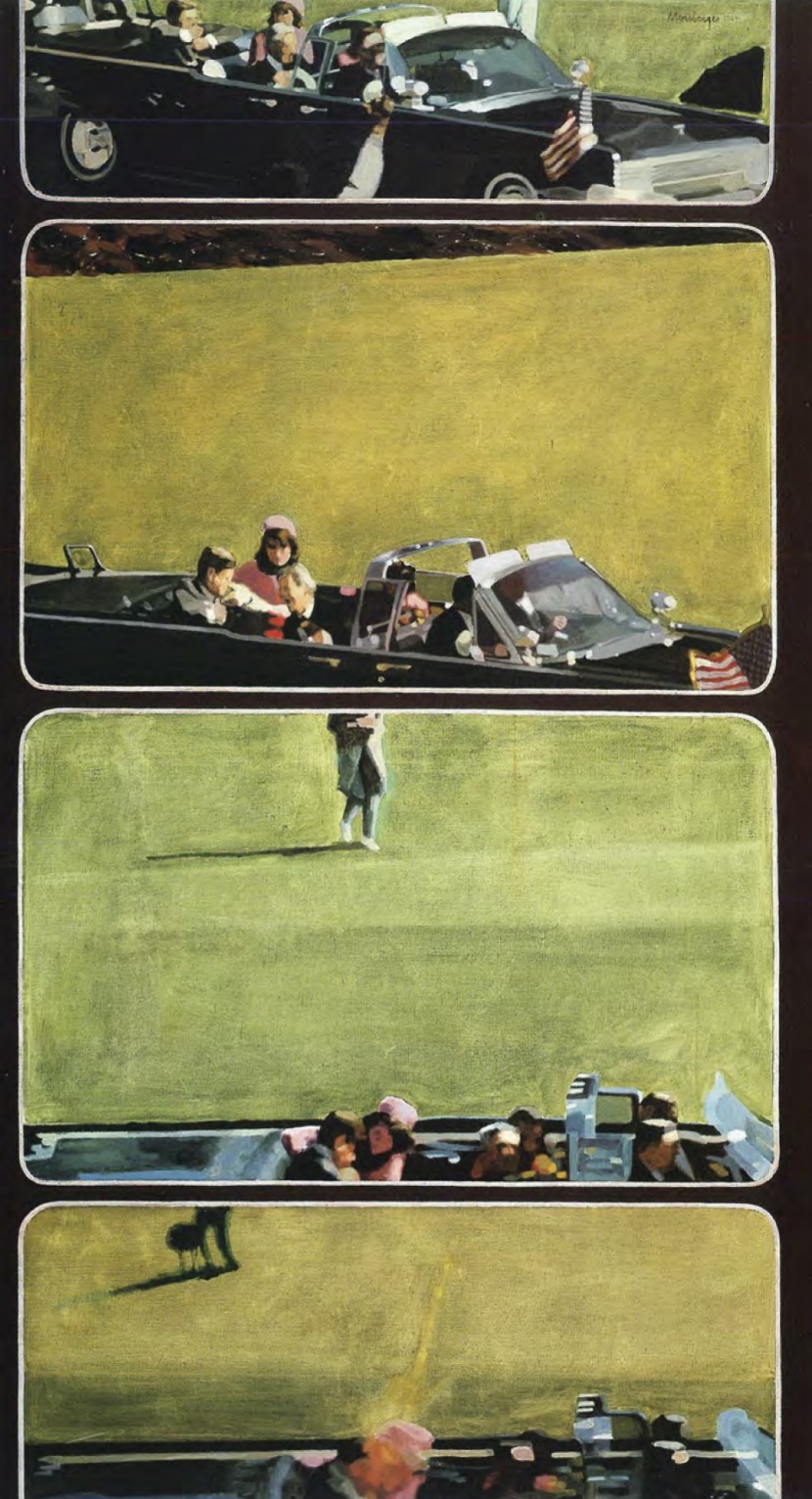

The 1960s in the USA began in a mood of optimism. Disillusionment, however, soon began to lap at the door of a White House that had been compared with King Arthur’s court at Camelot. Years later, the war in Vietnam and the campaign for civil rights were compounded by a series of assassinations (President Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy), widespread civil unrest, and often violent demonstrations in the streets and on university campuses. Morsberger engaged with these issues. The close attention he had paid to his training was now to bring dividends in an art that in a remarkably articulate and direct way both charted and expressed outrage at social injustice. His paintings provide a vivid record of a turbulent time in recent American history, and they are in effect exercises in political and social realism. It is unlikely that he expected his work ever to embrace this degree of immediate relevance, but it was his sense of social justice, his abhorrence of violence, and his personal courage, combined with the awakening and harnessing of his skills as an artist, that enabled him to portray so openly these dramatic events as a form of reportage. The paintings and drawings dating from his years at Miami University form part of a collective memory: namely, the exercising of public conscience.

(The Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio)

President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Morsberger’s instinctive reaction was to start a painting. Morsberger here asserts the primacy of painting as a proper visual record of a major historical event, and he was to continue this practice for the rest of the 1960s.

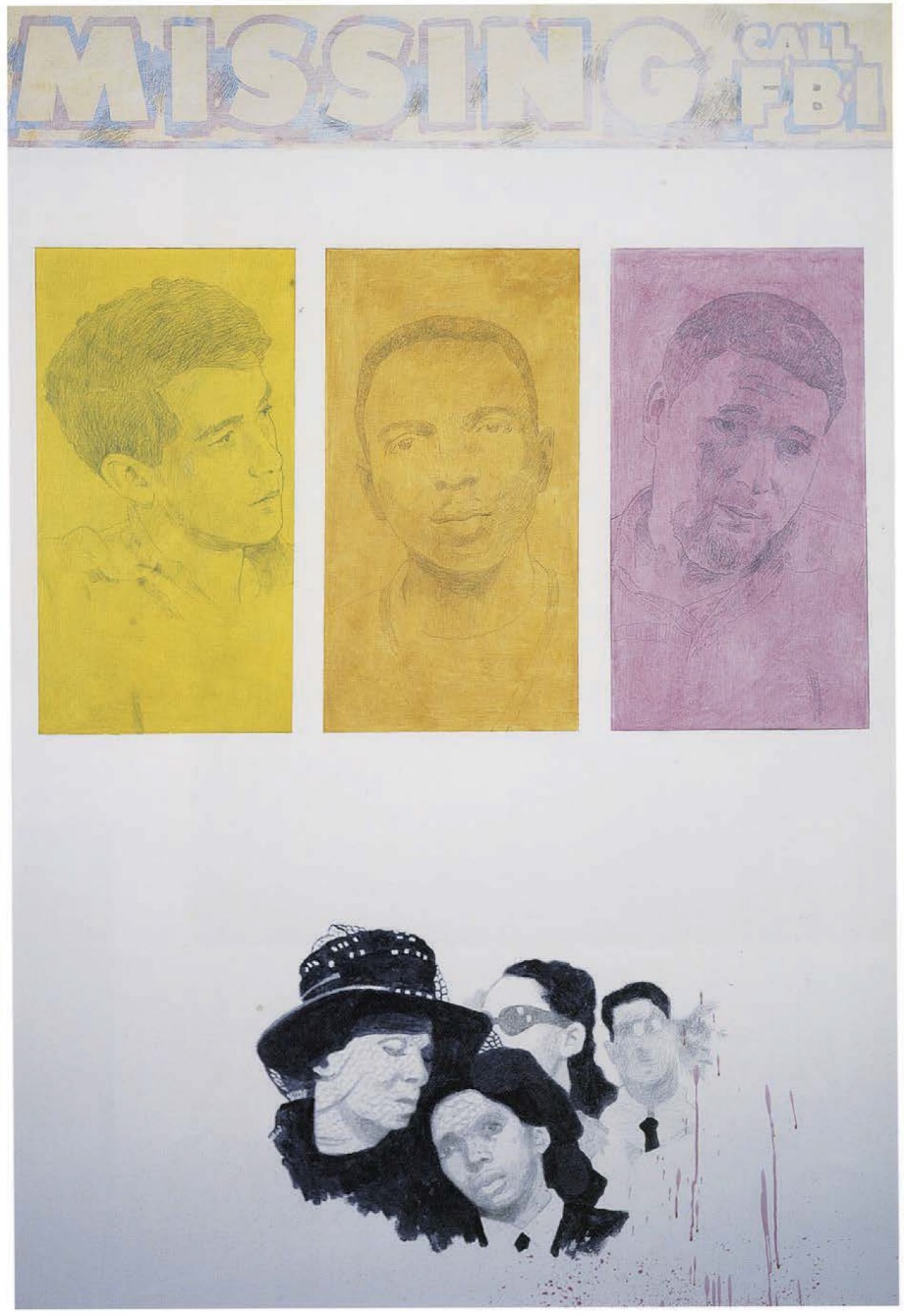

Missing (Nos. 1, 2, and 3) and Hey, Let’s Have Some Red Man! (The Arraignment) were undertaken while different, but no less consequential, events unfolded in 1964–1965. The focus of attention in these works is the civil rights movement in the light of the Civil Rights Bill, which was passed into law during the summer of 1964. In that same year at Oxford, Ohio, a conference was convened (June 14–29) known as “Freedom Summer.” Three of those attending the “Freedom Summer” project were Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman. The three men set out for the town of Meridian, Mississippi on Saturday, June 20 and went missing over the weekend. It became clear that they had been murdered while in police custody and with the complicity of the authorities, all allegedly members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Morsberger began Missing No. 1 before the bodies were found and based his image on the official poster issued by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. On hearing that the men had died, the artist, in despair, painted out the composition but then scraped the canvas to make it seem as though their photographic portraits were emerging, like ghosts, thereby creating a visual metaphor for their predicament. It is a subject that still haunts Morsberger: Missing No. 3 dates from 2002-03.

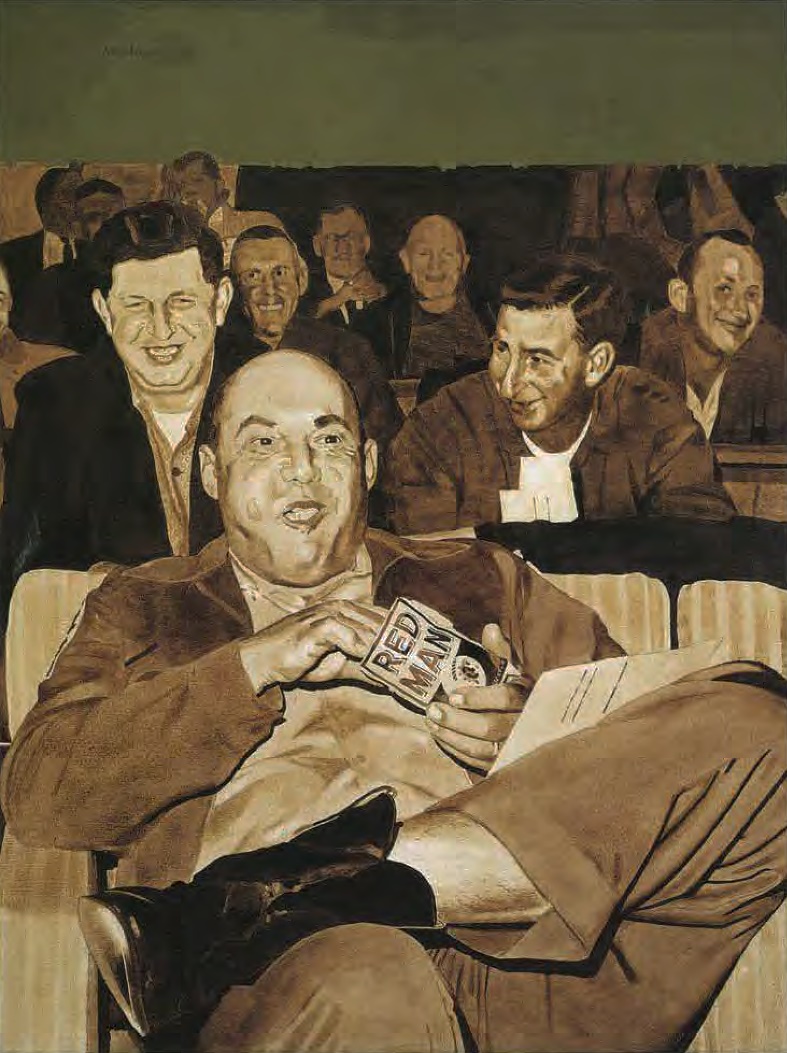

Hey Man, Let’s Have Some Red Man! (The Arraignment) is, essentially, a study in evil. These are the murderers of Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman at a preliminary court hearing. The bold foreshortening, the strong highlighting, and the leering faces — of the sheriff and his henchmen — create a sinister and frightening impression. These are portraits of people who regard themselves as above the law, untouchable and lacking any sense of contrition.

54 ½ x 41 ½ inches (Butler Institute of American Art)

For his involvement with this notorious case Morsberger won the Dorsey Award for 1965 given by the Oxford chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

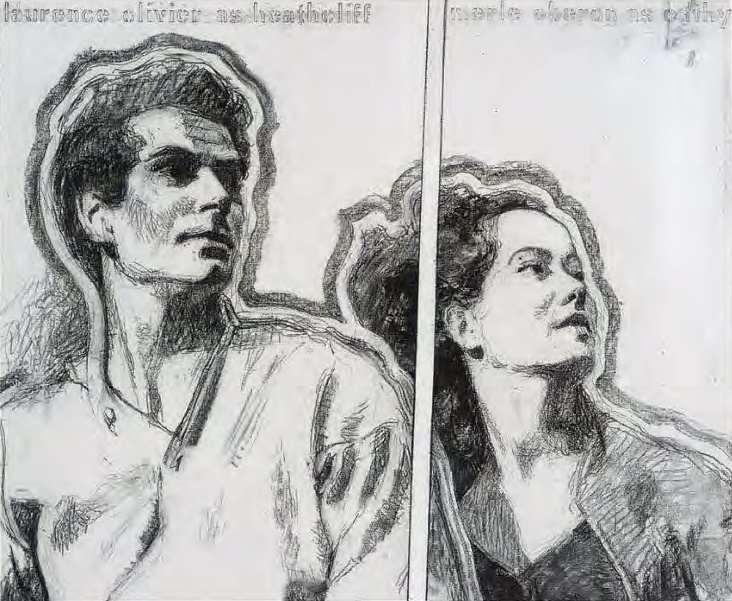

From this situation there is only escapism, as in romantic cinema — Wuthering Heights No. 2 — which is based on a poster for the film made by William Wyler starring Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon — or the future as represented by one’s own offspring. The Children’s Hour was posed by the artist’s children — Robert on the left and Wendy on the right. Both pursued careers in the arts (Wendy in ballet — she is now a member of the Dance Faculty of the Boston Conservatory — and Robert in music — he is now a composer and performer in New York), but here they are seen from above separated by an easel. The paintings along the right edge of the canvas are works by the children themselves, as indeed is the picture on the easel. The image betokens a spirit of optimism as the 1960s draw to a close. Morsberger has studied those issues that divide the world — war, social inequality, violence, estrangement — but there is solace in art just as there is hope in youth.

OXFORD (ENGLAND) AGAIN

On leaving Miami University, Morsberger held appointments in upstate New York at the Rochester Institute of Technology (1968–70) and for a shorter time at Rosary Hill College (now Daeman College) in Buffalo (1970). He was then appointed Master of the Ruskin School of Drawing at Oxford, England. This was his next important challenge. Morsberger was Master from 1971 until 1984 and during those thirteen years elevated the status of the Ruskin School in Oxford life. He was the sixth Master in the school’s history and the first American to be appointed to that position. Having been a student at the Ruskin School himself during the 1950s, Morsberger was aware of the institution’s strengths and weaknesses. Even though it was somewhat against the spirit of the times, he was determined to uphold the primacy of drawing as the basis of art, but what also concerned him was the lack of recognition that the Ruskin School had within the university. Its reputation was greater outside Oxford than amid the dreaming spires. The reversal of this situation became Morsberger’s mission in Oxford, and soon after his arrival he initiated a policy of Ruskin School resurgens. Oxford in the past had often resisted changes to its academic syllabus, but the debate held on March 8, 1977, ended with a majority in favor of having a studio degree in Fine Art (BFA) after three years (officially in Latin a Baccalaureus in Bellis Artibus). It was a historic moment and one with considerable consequences

A great deal of Morsberger’s time at Oxford was taken up with campaigning and lobbying for this change in the Ruskin School’s status. He himself as Master was elected to a Fellowship at St. Edmund Hall, a college founded in the thirteenth century, on the other side of the High Street. During his years as Master, Morsberger had two periods of leave: one (1976) was spent as a Fellow of the Carpenter Center for Visual Arts at Harvard University and the other as Artist in Residence (1983) at Dartmouth College at Hanover, New Hampshire.

(Brundin Collection, Oxford, England)

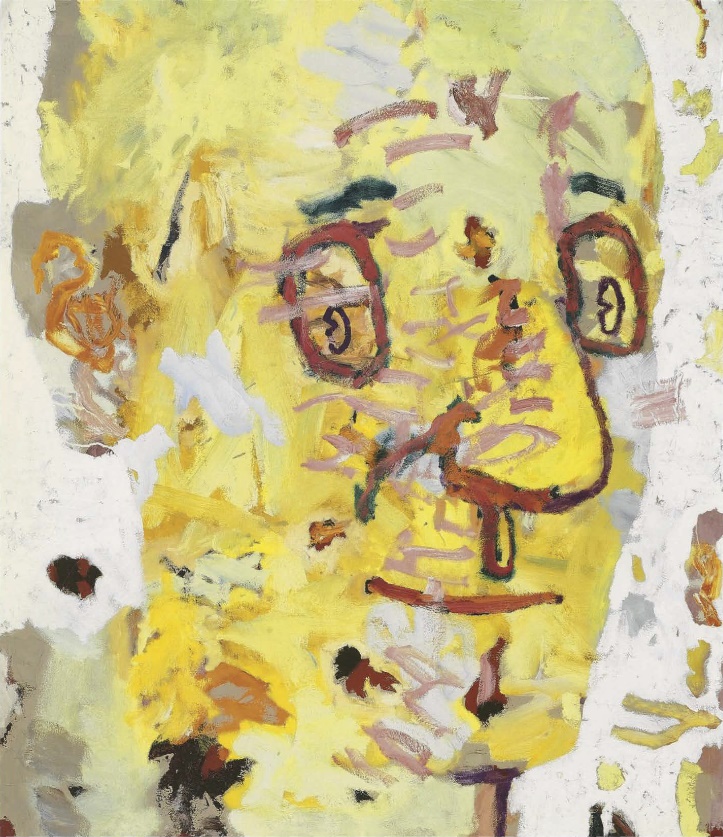

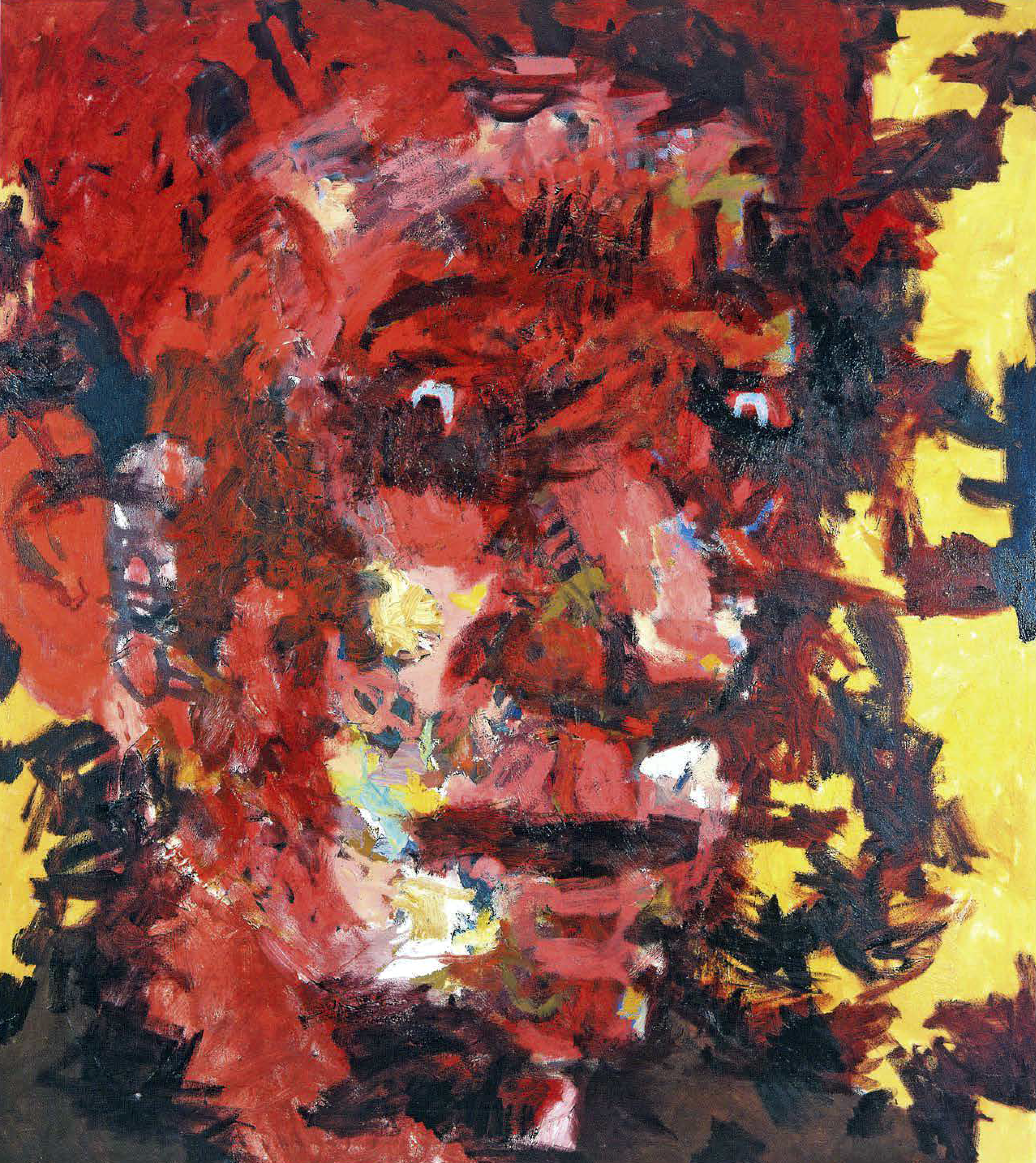

The evolution of Morsberger’s own work took a rather surprising turn during his second period in Oxford. This was partly as a reaction against the 1960s in his determination to escape from what he described as “a bellyful of all that tragedy, ugliness and unhappiness.” While he was fulfilling his obligations at the Ruskin School, his own paintings were moving toward an abstract style that was more concerned with color than with drawing. The experiences of the 1960s and the engagement in university politics led to the artist internalizing his emotions and thoughts, which now began to find an outlet in non-representational compositions diametrically opposed to the realistic paintings that had been done at Miami University. Significantly, Morsberger refers to these abstract paintings as “mindscapes” or “inscapes.” The latter term is one associated with the nineteenth-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, who was a student at Oxford University, where he had been influenced by Ruskin. A further connection between the poet and Morsberger lies in Roman Catholicism. Hopkins was received into the Catholic Church in Oxford in the late 1860s, and it was while he was in Oxford that Morsberger himself began to consider becoming a Catholic. His own conversion occurred in the mid-1970s, and he was accepted into the Catholic Church while at Harvard University in 1976.

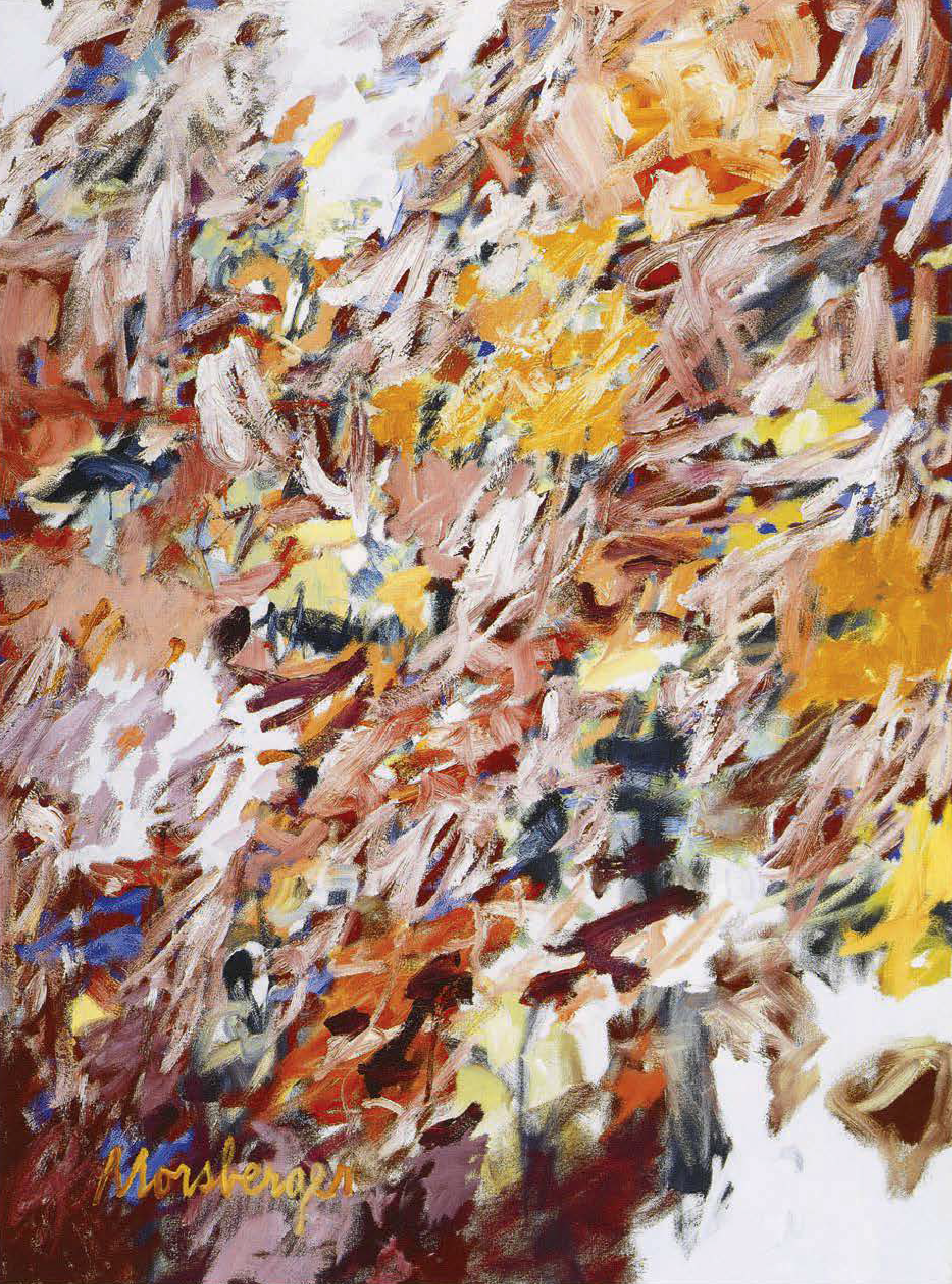

The approach to abstraction was made through a group of small landscapes, several of which were inspired by the countryside of Cornwall, in the southwest of England. The paint in these pictures has been rhythmically applied with broad brushstrokes loaded with pure pigment. There is a controlled dynamism in these taut compositions, which use color and texture to suggest recession and atmosphere. Emil Nolde and David Bomberg come to mind, but in these pictures Morsberger is discovering the potency of paint as a substance and the variety of ways in which it could be applied to the support.

Sometimes these paintings seem to retain residual landscape motifs — distant hills or bosky glades — but increasingly they depend on color and the materiality of paint itself. Vibrancy of the surface is often their touchstone, derived from the fusion or overlapping of a whole range of brushstrokes. An outstanding work in this category is Lightburst, with its refulgence of various tones of yellow applied with a brush and fingers in thick impasto. The surface is deliciously buttery and slippery, with the paint forming separate rivulets like ski runs that send the eye shooting off in different directions. The three-dimensional aspect of the surface imbues the painting with a physical quality of its own that extends its visual possibilities.

(Collection of Barbara Holder, Oxford, England)

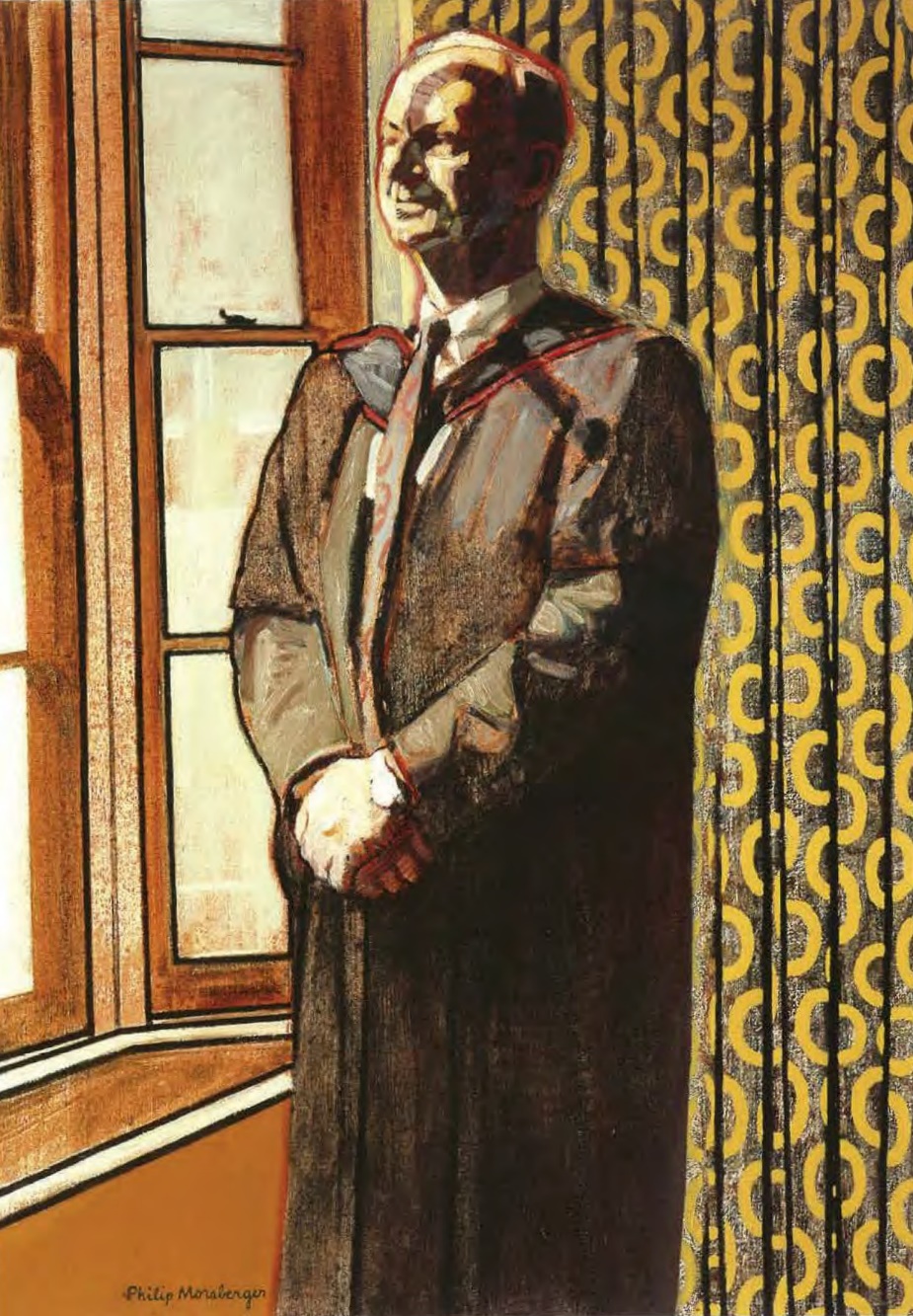

As Ruskin Master and Fellow of St. Edmund Hall, Morsberger would be asked to paint an official portrait of the Principal of the college, government research scientist Ieuan Maddock. A distinguished engineer and a Fellow of the Royal Society, Maddock is shown standing three-quarter-length in a window bay of the Principal’s Lodgings. The paint has been thinly applied on a rough absorbent canvas. The surface is dry and scumbled in parts. The composition in prismatic in its precision, with the figure secluded between the panes of glass and the patterning of the curtain. Clever use is made of the shadows cast by the framing bars of the window, which fall across the figure and help to unify the leftr and right sections of the picture. Clever, too, is the contrast between the panes of clear glass on one side and the patterned curtains on the other. The vertical axis is reinforced by the highlights on the face, the shirt, and the hands — all linked together by the tie.

Oil on canvas, 69 x 40 inches (St. Edmund Hall, Oxford, England)

The experimental aspect of Morsberger’s personal output in Oxford is represented by a small group of aleatoric paintings. The composition was outlined on the support first. Eleven colors were laid out on the palette and numbered. It was the throw of a dice that then determined the color to be used. The simplified contours and powerfully annealed colors equate with Post-Impressionist art and then with Pop art, but the idea of producing images by chance was one that had been explored during the Renaissance by Leonardo da Vinci and Piero di Cosimo. Eleven paintings were made according to this system. For Morsberger they amount to an investigation of the true values of color as squeezed directly from the tube, as well as a return to narrative subjects, which he had eschewed during the 1970s.

RETURN TO THE USA: RESOLUTION

On his return to America from Oxford in 1984 Morsberger was appointed Visiting Artist at the College of St. Benedict in St. Joseph, Minnesota, and at the neighboring St. John’s University at Collegeville.

However, after two years the offer of a Chair in Art Practice at the University of California at Berkeley (1986-87) took Morsberger away from Minnesota, and a further appointment in California as President’s Fellow in Painting and Drawing at the California College of Arts and Crafts (1987-96) kept him on the West Coast. The kinship that he had felt several years earlier with Bay Area artists could now be indulged, and one of the pleasures of these years was his regular meetings with Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, David Park. They were all artists who throughout their lives tried to balance the equation between figurative and abstract art. This, in fact, is a quandary that has underwritten a great deal of Morsberger’s own work and came to a head after his return from Oxford to the USA. A decade in California was brought to a close when he accepted the position of William S. Morris Eminent Scholar in Art (Artist in Residence) at Augusta State University in Georgia; he became Emeritus in 2002. This geographical meandering has given Morsberger the time and space to refine his style in the light of his experiences in Britain and the USA.

There are two main strands in Morsberger’s mature work: the triumph of narrative expressed primarily in a comedic vein and the further exploration of abstraction. These, however, are not mutually exclusive styles, even if they may at first appear to be so. As has been seen, the comedic vein had always been present from his earliest years. Abstraction was resisted in favor of drawing to begin with but was embraced in the 1970s and returned to again in the 1990s. It may be true that in strictly numerical terms the narrative paintings dominate, but equal emphasis should be placed on the abstract paintings. To all intents and purposes, the distinction is in many respects a false one. In recent years, when starting a painting, Morsberger has no preconceptions as to how the composition will develop. The application of paint and its manipulation on the surface suggest forms to him that can either assume a human shape or simply remain non-figurative. There is no longer any distinction between drawing as preparation and painting as an act of completion. The artist has developed the ability to draw with paint as a single unified act. The end product arrives of its own accord: figurative paintings have abstract backgrounds, and conversely abstract paintings contain within them elements of human forms. This comes about as a result of the creative process often carried out on a single canvas over many years: the juxtapositions are not contrived, measured, or premeditated, and on occasions it is difficult for the artist to know when the picture is finished. In many respects Morsberger is reverting to those lessons that he was taught, but at the time rejected, while at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in the mid-1950s.

(Collection of the artist’s family)

The return to comedic narrative in the early 1980s was really a reawakening of childhood interests. The comic strip tradition, widely acknowledged as an archetypal art form, has had some skillful practitioners who, like jazz musicians, have elevated the status of their art to a level of sophistication that made it a cross-over between high and low culture. The drawing of the figures and the setting had to be recognizable at a glance. Line, shading, and color, therefore, had to be applied almost stenographically, and so characterization was always exaggerated to This type of drawing was a more expressive way of treating the human figure and when used by artists as diverse as Roy Lichtenstein or Philip Guston on a large scale could have tremendous visual impact.

Morsberger’s renewed exposure to the comic strip tradition was accompanied by memories of his family upbringing. It is for this reason that many of the images in his recent comedic narrative paintings are of a private nature, which therefore gives these compositions a ludic quality. As in the comic strips, Morsberger creates a whimsical world based on memory. The titles are often suggestive of the past and the artist’s desire to come to terms with his own personal anxieties. The resulting images are not terrifying, as they are in Hieronymus Bosch, or as playful as those of Joan Miro, or as cerebral as Paul Klee’s. Morsberger’s art is more like that of Marc Chagall in its ability to give his personal reflections a universal application. Humor now replaces the social realism of the 1960s, but that does not reduce its relevance or its pertinence. As the artist has said: “You have to laugh to keep from crying.”

Color is a distinctive feature of the recent narrative paintings, but it is used to even greater effect in the pure abstracts dating from the 1990s onward. Morsberger now luxuriates in the warmth and richness of his colors: pink, yellow, green, gold, red, orange, brown, blue, purple, violet, and various mixtures of these. The colors sing on the canvas and in so doing reveal the artist’s admiration especially for Gauguin and Pierre Bonnard. There is a glorious climactic refulgence in these pictures that never tires the viewer or exhausts the artist.

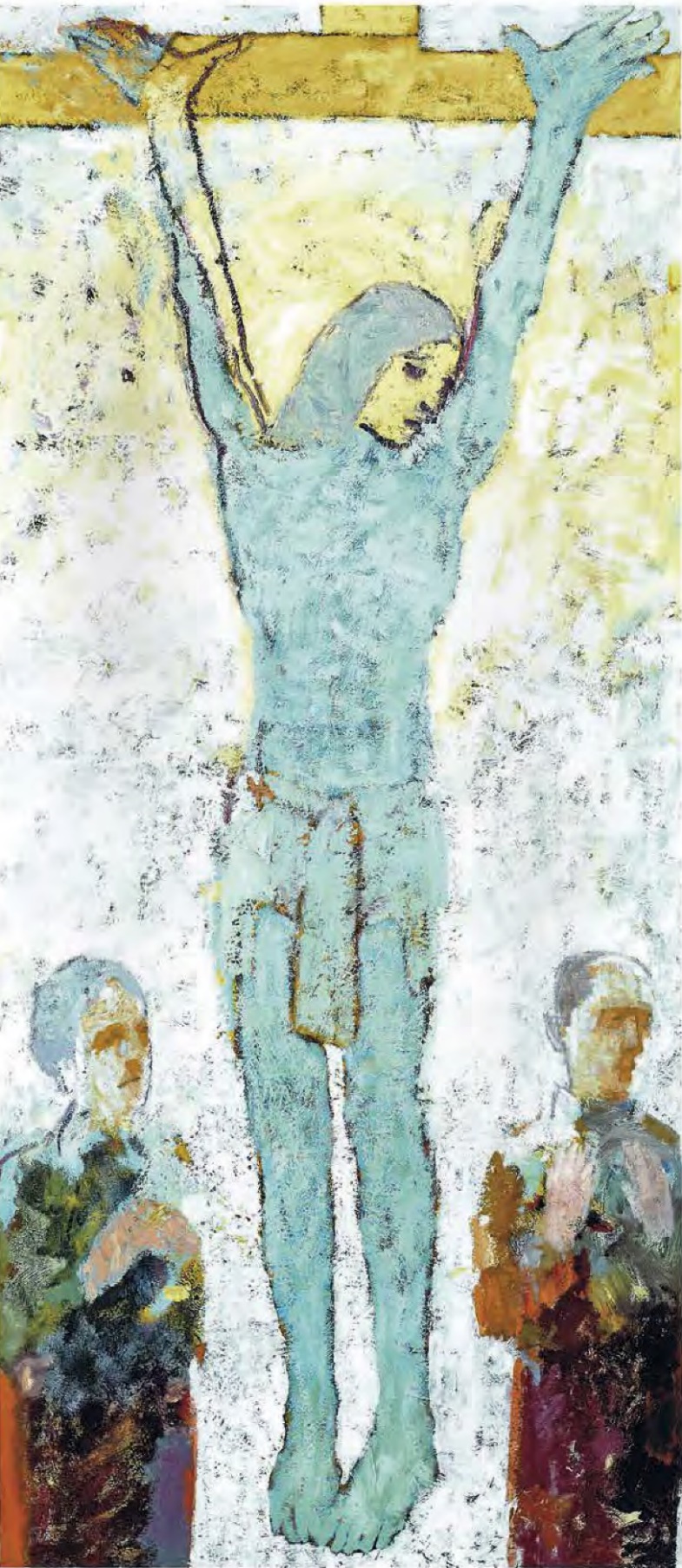

The titles of some of the abstract compositions have religious overtones, and it is important to appreciate that Morsberger regards himself as essentially a religious painter. In the narrow sense there are two pictures directly inspired by scripture, both entitled Golgotha. The canvas painted in 1994-2002 is a deeply moving work in which Christ is suspended from the prominent horizontal bar of the cross with the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist below on either side. The arms of Christ are almost vertical, as though being pulled out of their sockets, something emphasized by the narrowness of the canvas. The warmer colors used for the figures at the foot of the cross anchor them at the lower edge, while the light blue figure of Christ seen against a background of infinite space seems to soar upward. The delicacy of the palette is in stark contrast to the thick texture of the paint. The vertical bar of the cross behind Christ is omitted and is only suggested by a short section at the very top of the canvas. Because of this, Christ is both suspended and floating as if in the empyrean. Iconographically, this is the crucified Christ but also the resurrected Christ — Christus patiens and Christus triumphans in one image.

(The Greenville County Art Museum, Greenville, South Carolina)

Such a picture is an open declaration of Morsberger’s personal faith, but he in fact regards all his paintings as a deep-seated commitment to a life-enhancing end. The social realist pictures of the 1960s were intended first as records of terrifying historical events, but secondly as warnings. Morsberger regards such undertakings as the duty an artist has to perform in society — to act as witness for future generations. The narrative paintings, which contain a considerable amount of Christian imagery in an understated way, are, in the artist’s own words “all about resurrection, about getting there — by airplane, or by foot, or with the aid of a magic cloak or whatever; and equally the abstractions are about moving upward out of the dark and into the light. They’re all about death and resurrection.” Seen in its entirety, Morsberger’s oeuvre could be seen as a personal interpretation of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678).

One writer has referred to Morsberger’s pictures as prayers on canvas. The mood, however, is not necessarily reverential, and more often it is celebratory. Even now Morsberger feels compelled to paint every day. “I paint seven days a week. If I’m not painting life isn’t what it’s supposed to be.” There is also a close correlation between the act of painting and the act of worship. “When it’s going really well, one just feels like a conduit. This thing’s passing through you from wherever it comes and there’s a mystery about that. I’m just trying to make myself available to whatever it is.

Text excerpted from PHILIP MORSBERGER: A PASSION FOR PAINTING

by Christopher Lloyd, Merrill Publishers, 2007

Click here for full text with illustrations.