“Joseph Amar makes very sculptural paintings. His recent work is fixed to the wall in the tradition of two-dimensional paintings, but its material presence is effectively that of sculpture.”

— Muffett Jones, “Joseph Amar” essay in the 1987 exhibition catalogue, Similia/Dissimilia for the Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf, p.60

Amar was born in Casablanca in 1954. He was one of eight children born to Moroccan parents. His father, Victor, was a Sephardic Jew and his mother, Simone, also traced her lineage to Spain. The family’s language was French. Casablanca was home to the country’s largest number of Jews, but by the late 1940s the broader Arab conflict resulted in a steady exodus. In 1957 the family immigrated to Toronto. They were not well-off as Victor worked for the synagogue and Simone worked as a furrier at home.

Joseph was immersed in art and music, and in 1974 received a scholarship to study at the Ontario College of Art. Even though Minimalism was the dominant movement in painting, he was more drawn to “the European painters who were still working in what he saw as a more painterly, expressionist mode. Among those he admired were Alan Davie, Cy Twombly, Pierre Soulages, and Antonio Tàpies, whose sand painting seemed to be very sensual and not at all reductive. Now, Amar says, he understands that it was the concern for materials that drew him to all those works, and today he finds he has an even greater appreciation of them.”1

Growing up during the 1960s, Amar witnessed the explosion of disparate new movements reacting against Abstract Expressionism. The repercussions began with Pop Art and Hard Edge and saw the emergence of Op Art and Minimalism. But the reactions in Europe interested Amar the most, and he often said that the roots of his sensibilities were Mediterranean. While he held a deep love and respect for Picasso, no other artist had as great an impact on his painting as did that pioneer in Abstract Expressionism in Spain, Antoni Tàpies [1923–2012]. Tàpies had already begun mixing non-traditional materials in the early 1950s in a style he referred to as pintura matèrica, and by the end of the decade had established an international reputation.

From Italy there was Arte Povera, a movement whose artists revived the use of found objects credited fifty years earlier to that pioneer of the Dada movement, Marcel Duchamp. The Italians incorporated into their works found objects such as fabrics, paper, rope, clothing, scraps of wood, metals, and even rocks. Alberto Burri [1915–1995] pushed the collage tradition by incorporating a range of fabrics and plastics with a focus on burlap, tar, and pigments. By the mid 1950s he was pioneering the movement of collage toward assemblage as his works revealed an increasingly deeper third dimension by using plastics, charred wood, and scrap iron sheets. New York artists were well aware of Burri and Tàpies. It was also in the mid 1950s when Robert Rauschenberg [1925–2008] won recognition for his assemblages, which he referred to as “combine paintings” because they emphasized the emergence of objects from the surface of painted canvas.

This was the artistic maelstrom from which Amar emerged in the mid 1970s. He held a deep respect for several traditions. In addition to the innovations of Tàpies, he long admired the paintings of those leading figures from of the New York School such as such as Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, and Franz Kline. He especially loved the works of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko — the latter informing him of the spiritualist potential for Minimalism. From all of these painters’ works he drew a visceral response to the different techniques, mediums, and styles by which they transformed the traditional two-dimensional picture plane.

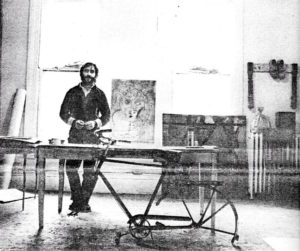

Here was a young artist who was intrigued by Duchamp, that seminal force who had exalted the common everyday object — the readymade — as the standard-bearer for the dematerialization of the art object in favour of focusing upon ideas versus materials. However, Amar was entirely focused on those everyday materials, even when Duchampian conceptualism was witnessing a resurgence. And he had little use for the then-dominant movement of Minimalism — which ignored material objects. By remaining so fully immersed his environment — so deeply informed by what he saw on the streets — he pursued an approach that was so different that his teachers held little drawing power for him. Instead, he turned to the streets, becoming a scavenger of culture’s detritus. As a result, he lasted only a few years until quitting art school and setting up his own independent studio on Queen Street West in Toronto. In that colourful urban neighbourhood he lived his art as he collected materials and experienced day-today sensations on the streets. He came to love the neighbourhood because it was “one of the best, with old buildings and people always throwing things out.”2

Amar’s closest friend was B.W. Powe, now regarded as one of Canada’s great visionary poets and writers. In a 1980 article, Powe wrote that Amar’s first floor studio was “a bright, cavernous room that had once been an after-hours club, visited by — it’s rumoured — Joni Mitchell, Mick Jagger, and some of the Monty Python gang. Now the walls are covered with paintings. The floor is so crammed that you have to make your way through a labyrinth, or a playground with an elaborate jungle gym set up.” Powe recalled, “When we were young, Joe and I, we used to play guitars to make money — and often played in a small place across the street from the Art Gallery of Ontario. Acoustic jazz — he was a fine guitarist.”3

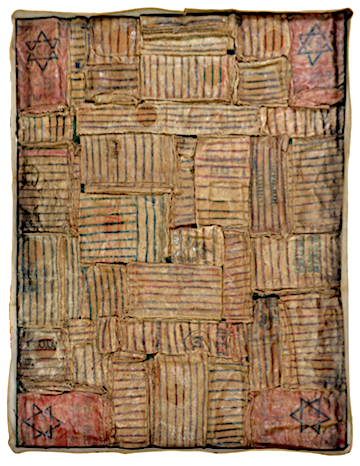

Amar was always pushing the boundaries, adding various materials to his now much larger oils on canvas. To those large supports he began applying heavier layers of mixed mediums, often including cement. It became increasingly necessary for those supports to become much stronger because he had begun — in the spirit of Arte Povera — to include numerous found objects in his works. Through the mid 1980s he strapped and glued to his canvases combinations of string, wire, rope, fabric, burlap, bed-sheets, shirts, burlap, wax, wood, metal, concrete, bottles — even pieces of wooden chairs, tables, stairs, and ladders — all projecting from the flat picture plane.

“Amar has from his beginnings as a painter let his chosen materials guide his instincts. In early paintings he took objects such as rope, burlap, and fire hose and affixed them directly to the canvas. These “combine” works drawing inspiration from Rauschenberg and Anselm Kiefer, attack the established flatness of the picture plane through exaggeratedly tactile means. So from the outset, the intent of Amar’s work has been to function in real space, letting physical presence take precedence over the comforts that might be afforded by more illusionistic, or optical, painterly devices.”

In short, here was Tàpies meeting Duchamp; Rauschenberg meeting Beuys.

Despite several successful gallery exhibitions in Toronto, by 1979 the importance of making a career move to New York became clear. Amar kept his studio in Toronto, and would later return to teach from time to time at the Ontario College of Art, but he and his wife, Dale, moved to Williamsburg, Brooklyn. At first, he worked as a carpenter and house painter. In 1981 he got his first big break — exhibiting with Ivan Karp, the owner of O.K. Harris Gallery — and in 1984 Karp would also give him a solo exhibition. In 1985 the Bess Cutler Gallery, the largest in SoHo, began to represent him and he would stay with the gallery for the rest of his short-lived career while also exhibiting in Boston, Atlanta, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Düsseldorf, and Paris. His works were acquired by the Guggenheim Museum and the Carnegie Institute and collected by such celebrities as Elton John, Yoko Ono, and Bianca Jagger.

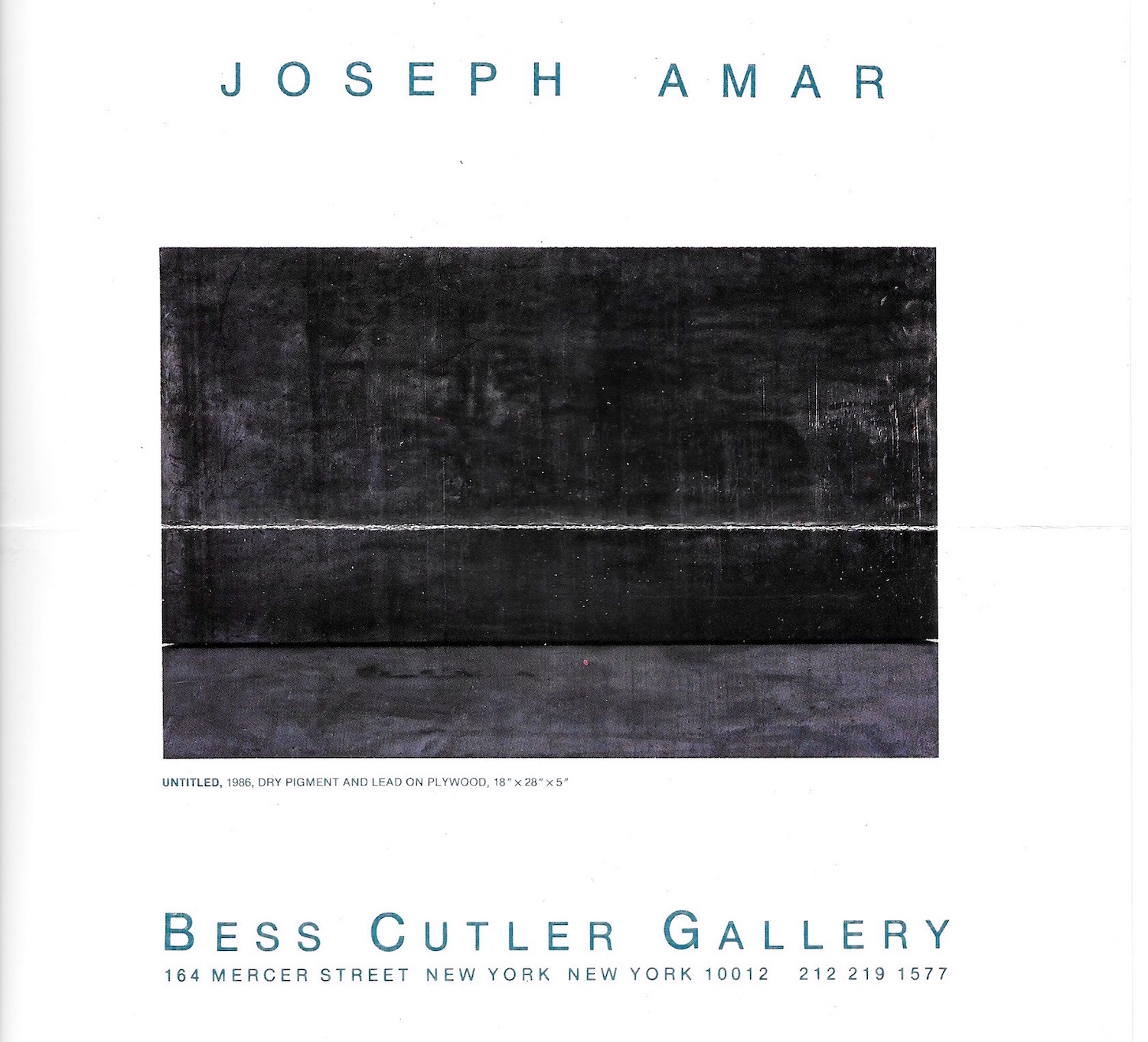

Amar found a fluid transition in his style around 1986 when the haute relief of his large three-dimensional wall constructions returned to flat surfaces, albeit in three dimensions. He limited his primary mediums to lead sheets on wood panels, often accompanied by layers of wax, graphite, and oil paint. Exhibitions O.K. Harris and Bess Cutler Gallery caught the attention of curator Rainer Crone, who in 1987 included Amar’s new works in a major exhibition — Similia/Dissimilia — which originated at the Städtische Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf, traveling to Columbia University, the Leo Castelli Gallery, and Sonnabend Galleries in New York. Crone generated a dialogue between the older and newer generations of painters, sculptors, and photographers.

Jones aptly noted that “His paintings from this early period are very large and involve many layers of materials, including found objects that he strapped to the canvas…as if the paintings would gain power by physical accumulation.” She went on to accurately observe that Amar’s stylistic evolution was not an abrupt one because both his early and late works reflected layers of “cultural signifiers,” noting, “There is a sense of compression about his work as if — to use a nuclear simile — his early work had been run through a cyclotron until the atoms compacted. Lead is, literally, a very heavy medium….Amar became interested in lead as a communicative medium for a number of reasons. He appreciated the material’s alchemical associations; its toxicity to the human system could alter consciousness and ultimately translate life to the spiritual plane. Its contemporary associations are equally relevant. As an industrial substance, lead has assumed major role in the nuclear age; though toxic in itself, it ultimately shields from an even deadlier substance.” 6

Within just several years of his first break-out exhibition in New York, Amar found himself launched by Similia/Dissimilia into a greater limelight with a host of artists whose names are well-known today. The styles of those well-established artists born in the 1920s and 1930s ranged from Dada to Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism. Among their ranks were Joseph Beuys, Richard Artschwager, Donald Judd, Yves Klein, John Chamberlain, Robert Ryman, Jasper Johns, and Dan Flavin. All of Amar’s closest peers from his emerging generation are well-known today, such as Anish Kapoor, Philip Taaffe, Roni Horn, Peter Halley, and Francesco Clemente.

Amar’s works stood out from Neo-Expressionism and Neo-Geo because he took the Minimalist dialogue to a deeper level. In her essay on Amar for the book published for Similia/Dissimilia, Muffett Jones described the young artist’s discourse with Minimalism as expressing a kind of nostalgia for “the formalist issues of Abstract Expressionism, tied to a more conceptual, anti-illusionistic postmodern stance.” Referring to a particular work, she noted that “its apparently formalist and superficially reductive façade recalls the early sculpture of Donald Judd, but this is like a Judd piece from a Blade Runner future, a post-apocalyptic cultural container.”5 Indeed, Ridley Scott’s dystopian “Blade Runner” from 1982 was one of Amar’s favourite films, along with “Fellini’s Casanova” from 1976.

In the two years following Similia/Dissimilia six galleries in New York were showing Amar’s work as well as galleries in Atlanta, Boston, Baltimore, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. For an exhibition catalogue in New York in 1989, critic John Zinsser wrote:

“Amar’s recent lead pieces exploit the surface qualities inherent to that elemental metal. The beauty of lead as a readymade material is counterpoised against the authorial intentions of the artist, with Amar gently scumbling his surfaces and introducing thinly painted washes. In all cases, the authority of the metal remains paramount. These box-like constructions, many of whose facings are marked in broad vertical stripes, can be seen as a material response to the sculptural questions raised by the paintings of Sean Scully…As a young artist hitting his stride in the 1980s, Amar has progressed steadily forward through a strategy of reductive refinement. He has explored the rigorously narrow confines posed by the literal nature of his working materials (which have included lead, copper, steel, wax, and wood). Although such investigations into painting and sculpture are no doubt nurtured by the lessons of 1970s Minimalism, Amar’s formal decisions are less determined by a specific conceptual agenda than they are by a more lyrical poetic drive. Foremost, he works as a painter, finding strength in the unconscious and in the unprogrammatic.”7

In 1990, the catalogue for Amar’s exhibition in Paris featured an essay by Joshua Decter entitled “Discreet Geometries” that revisited Amar’s unique relationship to Minimalism. Calling his works “object/paintings” he pointed out that “While Amar’s work would seem to demonstrate a strong relationship with what is often associated with the primary signature idiom of Minimalism — i.e., a reductive, unitary geometricism — it maintains a far less programmatic attitude towards the vicissitudes of anti-composition and gestalt effects; Amar’s practice affords a space for intuitive decision-making, thereby allowing for the insinuation of “non-rational” permutations within an overarching framework of geometric rationalism.”8

In June of 1991 Amar enjoyed two more exhibitions in New York. Less than two months later a drunk driver collided with Amar’s car in a horrific crash. Both the driver and Amar’s wife were killed instantly. Amar and his young daughter were rushed to the hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, in commas. Once stabilized, they were airlifted to Toronto where his daughter eventually recovered — but Amar was paralyzed from the neck down. He had limited use of his right arm and eventually learned how to “speak” again with the help of a computer’s voice synthesizer. It was owing to this tragic episode that Amar’s pioneering works fell from sight and into the deep abyss of storage. Now, decades later, the remarkable collection of a young man whose career was cut short is being brought back to the limelight and being celebrated.

— Peter Hastings Falk, 2016

Exhibitiion invitation, Bess Cutler Gallery, New York, 1989

Footnotes

1 Jones, Muffett. Essay, “Joseph Amar” in Similia/Dissimilia: Modes of Abstractions in Painting, Sculpture and Photography (New York: Rizzoli, 1987, p.60)

2 Parker, Andrea. “Mediterranean Influence in His Art” (Toronto: unidentified newspaper clipping, 1979)

3 Powe, B.P., email to the author, 11 February 2016

4 Zinsser, John (New York: for exhibition catalogue at Bess Cutler Gallery, 1989)

5 Jones, p.62

6 Ibid., p.63

7 Zinsser

8 Decter, Joshua (Paris: essay, “Discreet Geometries” in exhibition catalogue, Joseph Amar, Oeuvres Récentes at JGM Galerie, Paris, 1990, p.22)