Don ZanFagna’s utopian spirit and environmental consciousness were the driving forces behind an extraordinary collection of collages discovered by his family shortly before his death in 2013. His collection is presented here in three highly developed and related series: The Manhattan Project (1969–1973); The Cyborg Series (1968–1974); and, The Pulse Domes (1970–1979). These series reflect ZanFagna’s savvy of the rapid technological changes taking place in the 1960s and 1970s — and they are eerily prescient of current environmental realities. Together, these compelling collages present a dynamic amalgam of surrealism, futurism, constructivism, graphic design, and psychedelic Pop by an idiosyncratic genius that defied being pigeonholed in any established category.

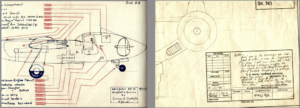

Growing up in Rhode Island, at age fifteen, he was producing technical drawings of airplanes. In 1950, he was a star quarterback at the University of Michigan and an ace third baseman. He was offered contracts by the 49ers, the Cardinals, the Dodgers, and the Red Sox. But he turned his back on it all that to pursue a degree in Art and Architecture and never looked back.

ZanFagna went on to serve as an Air Force fighter pilot during the Korean War, during which time he also painted, made woodcuts, and exhibited his works. He then successfully applied for a Fulbright Grant to study painting in Italy, where he headed upon his release from service in 1956.

In the following year, he studied at the Academia di Belle Arte, with artists Afro and Mirko Basaldella, and exhibited at Rome’s renowned Galleria Schneider along with other Fulbright artists including Lee Bontecou and Wolf Kahn. The Uffizi Museum in Florence awarded him a summer research grant to study the originals of old masters. He continued his studies and traveled to museums in Siena, Perugia, Pisa, Venice, Assisi, and Padua. He and his wife of 56 years, Joyce, were married at the Campidolgio in Rome.

Returning to the United States in 1958, ZanFagna began pursuing his MFA in painting first at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana. His son, Robb, was born in 1959. ZanFagna finished his studies at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. There, the Rex Evans Gallery and the Comara Gallery represented the popular emerging artist and gave him several one-man shows. His lyrical, organic paintings interested many Hollywood notables, and one of his ardent supporters was producer George Stevens, Jr.

During his sojourn in California, in addition to his several abstract expressionistic paintings, he produced marvelous graphics from his own press and an unusual ink and watercolor series he called Rust Root. His work was collected by museums in Los Angeles, Pasadena, Palm Springs, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, and Long Beach. Private collectors included various Hollywood actors, Rodeo Drive interior designers, and Los Angeles corpo rations, as well as the famous jazz club, “The Lighthouse” in Hermosa Beach. West Coast Jazz drummer Shelly Manne contracted with Don to do the backdrop for his LA club the Manne Hole. Don planned to incorporate designs from his “Immersion in Light” series but the club burned before the backdrop was begun.

rations, as well as the famous jazz club, “The Lighthouse” in Hermosa Beach. West Coast Jazz drummer Shelly Manne contracted with Don to do the backdrop for his LA club the Manne Hole. Don planned to incorporate designs from his “Immersion in Light” series but the club burned before the backdrop was begun.

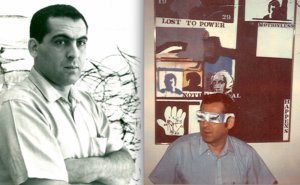

In the mid 1960s ZanFagna returned to the East Coast, but this time to the Big Apple. He lived among abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock, Larry Rivers, and Joan Mitchell, and graphic designer-turned-Pop-artist Andy Warhol. A jazz lover, he befriended jazz musicians including bassist Charlie Mingus, who always saw that he got a front row seat and a free drink. Meanwhile, in his studio on Long Island, he continued to create many individual works, including expressions of protest and concern in oil on canvas. He also created a noteworthy series of drawings called “Energy Dreams.”

In the late 1960s he began a teaching job at Rutgers University. By the 1970s he had moved up the ranks at Rutgers to become Chairman of the Art Department at the Newark campus. There, he designed a new art complex that housed visual arts, music, and drama. He also exhibited his famous seminal environmental piece, Last Grass, at the New Jersey State Museum’s Invitational Art from NJ

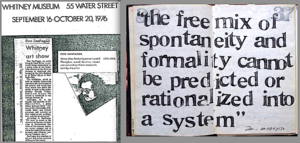

Soon after, he delved deeper into his passion – ecology. He was the principal speaker at the first Earth Day in New York City, alongside Margaret Mead and Ralph Nader. His concern for the environment spawned a series of sculptures called MicroMax. One of these sculptures, called Micro-Max Pocket Systems I and II, was exhibited at the Whitney Museum’s “Art World 1976” in New York City. Included within this Plexiglas sculpture was the prophetic concept “All the Books of the World in the Palm of Your Hand.”

Later in the 1970s, ZanFagna pondered the effects of existentialism in the academic and theoretical world, which he represented with a series of drawings called The Seated Man. He also continued his involvement in humanitarian and political activism, this time traveling to Sweden to help ferry supplies to Biafra during the Nigerian civil war.

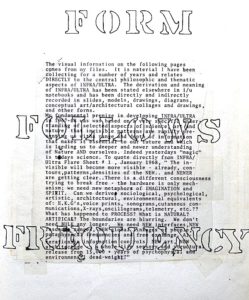

In the early 1980s, as a professor of architecture at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture in Brooklyn, his emphasis was on ecologically sound architectural  designs. He created a series of environmentally themed conceptual art and sculpture, which became a part of a solo exhibition at Pratt. He also continued to plan for the creation of the Infra Ultra Architecture and Design Foundation, a place where students could learn about and develop environmental designs in art and architecture. His concepts meshed well with Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes.

designs. He created a series of environmentally themed conceptual art and sculpture, which became a part of a solo exhibition at Pratt. He also continued to plan for the creation of the Infra Ultra Architecture and Design Foundation, a place where students could learn about and develop environmental designs in art and architecture. His concepts meshed well with Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes.

During his lifetime ZanFagna enjoyed more than 215 solo and group exhibitions across the United States and internationally. His utopian spirit and environmental consciousness were the driving forces behind an extraordinary collection of collages discovered by his family shortly before his death in 2013. His collection is presented here in three highly developed and related series: The Manhattan Project (1969–1973); The Cyborg Series (1968–1974); and, The Pulse Domes (1970–1979). These series reflect ZanFagna’s savvy of the rapid technological changes taking place in the 1960s and 1970s — and they are eerily prescient of current environmental realities. Together, these compelling collages present a dynamic amalgam of surrealism, futurism, constructivism, graphic design, mythology, and psychedelic Pop by an idiosyncratic genius that defied being pigeonholed in any established category.

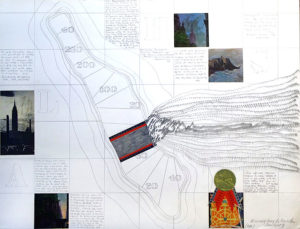

When ZanFagna was creating The Manhattan Project (1969–1973), he also founded the Center for Ecological Action to Save the Environment (CEASE). In 1970 he joined Ralph Nader and Margaret Mead as a speaker at New York’s first Earth Day Teach-In at Union Square. He was inspired to write his own mock press release for The Manhattan Project and dated it April 19, 2084:

At 2:28 PM, Eastern USA time and after 28 years of frantic efforts by Globenterprise, the island of Manhattan, New York, disappeared into the sea. With hardly a sound emerging from the Grand Old Lady and with millions of local residents and tourists lining the shores of the Hudson River, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, Staten Island, and the New Jersey coast, the once proud symbol of American freedom and culture crumbled slowly to its watery grave.

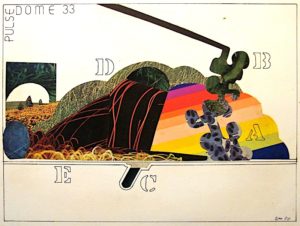

The Pulse Domes (1970–1979) reveal ZanFagna’s obsession with the futuristic concept of “growing your own house.” Voluminous sketchbooks spanning decades of research on world indigenous architectures, insect architecture, wombs, caves, tunnels, and volcanoes were aimed at uncovering a form of sustainable human architecture that would be in harmony with natural processes. These vividly imaginative collages (with drawing and painting) show homes created, constructed, and maintained entirely by all organic processes. It is remarkable to note that this series was created nearly twenty years before the first self-sustaining research environment, Arizona’s Biosphere 2, and nearly forty years before our current “Go Green” revolution.

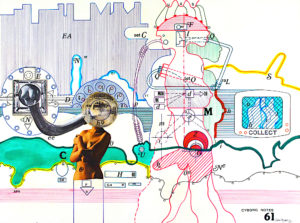

The Cyborg Series (1968–1974) integrates creativity with futuristic warnings. Here ZanFagna’s collages serve as “cybernetic metaphors” that focus on the future problems that DNA mixing might cause. They are signals or warnings of things about to wrong. The artist wrote, “These works incorporate humans and machines, cloning, eco-architecture and landscape, biology and technology and make use of dark humor, skepticism, irony, and futuristic symbolism.” The resulting Cyborg environment that ZanFagna constructs shows entities that have lost their humanity and sexuality, but mechanically still reproduce new “humans” replete with nuts, bolts, and robotic controls.

His writings overflow with remarkably prescient descriptions of such things as the development of the personal computer. For example, in 1976, more than thirty years before the Kindle was released, ZanFagna exhibited an ersatz gizmo containing “all the world’s books in the palm of your hand” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. He also predicted the wide-spread use of solar panel technologies and the use of biological processes such as algae and ethanol to generate energy. To be sure, every plan, model, and prototype was derived from a rigorous, disciplined scholarship. He traveled the world researching standing stones, Mayan ziggurats, and various ecological systems in search of underlying structures that might be adapted by humans to create habitats informed by these “invisible” or unknown processes. He scrutinized books, manuscripts, proceedings of conferences, and the popular press as he sought to uncover anything that might illuminate some aspect of his quarry on the art-human-ecology-technology continuum.

In 2010, when ZanFagna retired to Charleston, South Carolina, he and his family began to examine his vast archive of notebooks, journals, drawings, photographs, artworks, collages, models, and ephemera — which now form the ZanFagna Foundation Trust. During the next two years the collages created by this restless provocateur and inventor formed a traveling exhibition to the Aspen Art Museum, the Tampa Museum of Art, and the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston School of the Arts.

— Peter Hastings Falk