The Master Colorist Who Was a Transcendental Botanist

Youth: From Spain to America

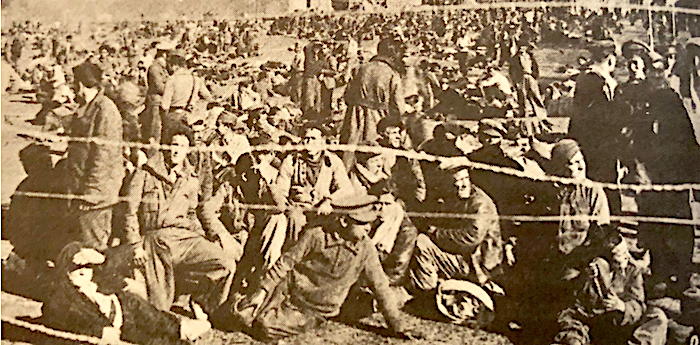

Franco’s brutal fascist uprising continued to wage its reign of “White Terror,” murdering as many as 400,000 “leftists” Republicans. Picasso memorialized the tragic period with his iconic mural, Guernica. Gil was four years old; his brother Pedro three and sister, Teresa, five. Had they remained in Madrid they would surely have been arrested and killed. Martha’s husband, José — a famous botanist at the University — told them to flee quickly while he remained behind. Martha joined nearly a half million refugees who escaped to France.

Soon thereafter, José managed to leave Spain as a scientist in order to resume his high altitude expedition in the Andes mountain range of Colombia to collect plant specimens. But José feared for his family, correctly sensing that the Germans would soon occupy France. His wife and children were among the refugees who had been taken in by families in Paris. Thousands of Jews had already been fleeing Nazi Germany on passenger liners hoping that they would be accepted in Cuba or South America. José sailed the other way, retrieved his family, and returned to Bogotá, Colombia. By June, 1940, France had fallen. Afterwards, thousands of Spanish refugees in France were captured by the Nazis and sent to the concentration camps. In 1947, when Gil was twelve years old, the family relocated to the United States after José accepted a position at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. They settled in Bensenville, a small town just northwest of Chicago.

Discovering His Passion in Art: From Harvard to the Washington Color School

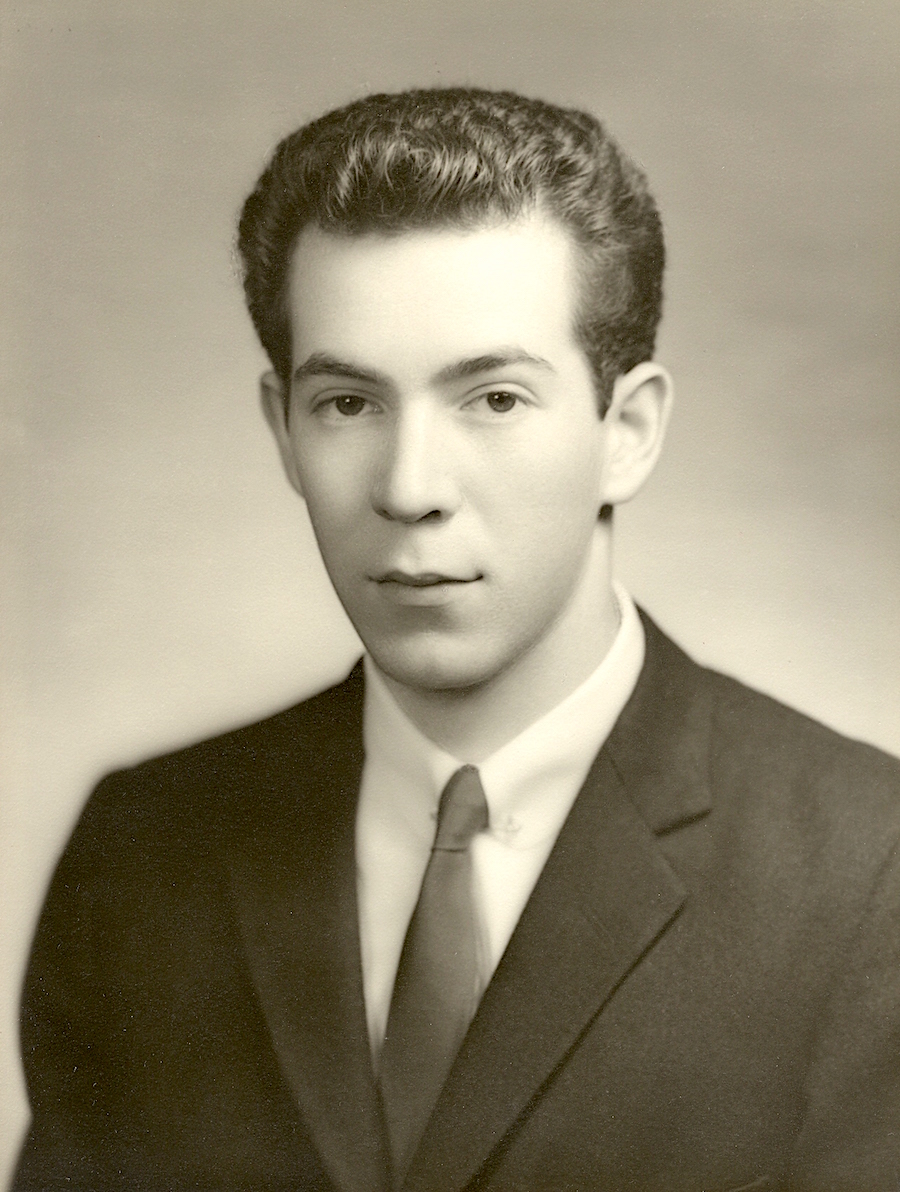

Upon graduating from the local high school in 1953 Gil attended Harvard, at first intending to follow a career in medicine but then switching to the fine arts. Always sketching as a boy, his interest may have been triggered by courses in philosophy and a popular seminar on color theory taught by Professor Richard F. Brown. He was undoubtedly moved further by the 1955 Matisse exhibition at Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, as that master of color had died just the previous year.

Certainly, the environment for the fine arts was quite different as Cuatrecasas entered Harvard because two wars had just ended. No sooner had Paris been liberated from the Germans than Picasso, Matisse, Breton, and Duchamp surrendered a parallel war to a group of irascible young Abstract Expressionists in New York — led by Pollock, Rothko, DeKooning, and Kline. From that point on New York would be the epicenter of the art world. Esteban Vicente [1903–2001] remains the best-known Spanish artist to have fled Madrid for New York, becoming a member of that group of action painters in 1936. However, for most of Cuatrecasas’s generation of Spanish artists born in the 1920s–30s few would escape the pervasive influence of that great triumvirate of Spanish modern masters that preceded them: Picasso, Dalí, and Miró. As far as Abstract Expressionism was concerned, the strongest works in Spain included the heavily-textured mixed-media abstractions by Antoni Tàpies [1923–2012] and the figurative expressionism of Antonio Saura [1930–1998]. Notable, too, are the floating geometric shapes of Albert Ràfols-Casamada [1923-2009], the heavily-textured collages of Manolo Millares [1926–1972], and the exuberant play of circular shapes with action painting in the work of Joan Tharrats Vidal [1918–2001].

Cuatrecasas appreciated the seminal importance of Spain’s modern masters but felt compelled to follow a different path. Upon graduation from Harvard in 1957 he entered the highly selective graduate program at the Yale University School of Art, which had been headed by Josef Albers since 1950. Albers had immediately established a distinguished faculty and attracted important visiting teachers such as Willem de Kooning and Stuart Davis. Cuatrecasas was fortunate to have studied under Albers during the master’s final years at Yale. Even though Albers’s influence was profound, Cuatrecasas was restless and anxious to establish himself, so just before graduation he suddenly left Yale and set up a studio in the garage of his parent’s home in Washington, D.C. They had moved to the capital after his father accepted a position as a chief botanist with the Smithsonian Institution. Gil attended the Corcoran School of Art and became associated with a group of artists — including Gene Davis, Thomas Downing, Sam Gilliam, Kenneth Noland, and Morris Louis — who would later become known as the Washington Color School. From 1960–1961, he studied in Mexico City under a grant from the Pan-American Union (now the Organization of American States). When he returned to Washington he rejoined his colleagues and in 1964 their exhibition, “Nine Contemporary Painters,” appeared at the Pan-American Union curated by Lawrence Alloway of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. James Harithas, the director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, had long been following Cuatrecasas’s development and in 1965 gave him a solo exhibition. “Very few people know how to paint,” commented Harithas, “and Gil was one of the brighter students who really stood out as very promising.” 1

A Unique Style Emerges in Spain

Unfortunately, parallel with Cuatrecasas’s early success he suffered some depressing experiences. First, the promise of marriage to a woman with whom he had fallen in love while at Harvard fell apart. Next, his dealings with art galleries, and the related financial issues left him deeply disenchanted. He sought to avoid the increasing social obligations that two significant exhibitions had placed upon him and shunned dealing with galleries. In 1966, shortly after his solo exhibition at the Corcoran, he moved to Barcelona, living in the apartment of an aunt — Montserrat Cuatrecasas — with whom he had a close relationship. He promptly converted one of her large bedrooms into a studio. His aunt, who became the first Director of the Miro Foundation’s Library and Documentation Centre at the Centre for the Study of Contemporary Art, became so impressed by the quality of his work and the intensity of his commitment, that she suggested a major move. In 1970 she invited him to move into her large villa outside of Torino, Italy. There she allowed him to transform most of her home into a huge studio — thereby enabling him to paint very large canvases. This expansive environment in Torino would prove the catalyst for the fulfillment of his artistic vision. During the next seven years the style that had begun to emerge in Washington and Barcelona entered its full bloom. Focused and prolific, Cuatrecasas covered the vast floors with canvas and produced hundreds of large paintings from eight to twenty-two feet long. Eventually, layers of paint concealed the beautiful marble floors and stacks of stretched paintings leaned against all the walls.

Understanding the wellspring of any artist’s creativity is often a difficult task. And Cuatrecasas compounded this task because he was purposely discreet; refusing to speak about his sources of inspiration or the messages he wished his paintings to impart. His role as a colorist began at Yale with Albers and continued to develop in Mexico and Washington. However, it is clear that the shapes he imbued with color reveal that their fountainhead was his exposure to and fascination with his father’s lifelong obsession with discovering and documenting what came to be 126 new species of a rare plant form that only exists at an altitude of about 15,000 feet in the northern end of Andes mountain range — the espeletia, commonly known as the frailejón. This bizarre plant produces daisy-like flowers on stalks that are protected by a central cluster of long broad leaves radiating like a crown sitting atop a thick cactus-like column nearly twelve feet tall — the whole appearing as a fantastic surreal sculpture. José’s pioneering work on this rare plant earned him accolades as one of the world’s great botanists. His magnum opus, A Systematic Study of the Subtribe Espeletinae, took a lifetime and was so massive that it was published 17 years posthumously in 2013.

It is not surprising, then, that his boys found great pleasure examining various life forms with the microscope given to them by their father. Gil was particularly fascinated by his father’s botanical drawings of the plant’s parts, especially its distinctive broad leaves. In Washington, Gil began to tap his father’s extensive herbarium of specimens of the leaves of the frailejón and began incorporating them with color paper fragments in a series of collages — an exercise learned from Albers.2 In addition, during the early 1960s he was commissioned to produce nearly one thousand exacting pen-and-ink botanical illustrations for a series of his father’s publications — and at least five-hundred of these drawings are in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. The use of the herbarium for documenting a pharmacopoeia of Andean culture also had an impact upon Gil’s younger brother, Pedro, who became a renowned research pharmacologist.

Stylistically, therefore, many of the paintings in the Torino series reach beyond the purely non-objective, as they draw inspiration from the familiar botanical shapes of Cuatrecasas’s youth. The same broad leaves reappear consistently in his paintings but they are often not immediately recognizable. Cuatrecasas’s colleague Morris Louis also created a stylistically similar floral series but he used the very different technique of pouring thinned acrylics on raw canvas. These paintings, composed of overlapping leaf-like shapes of color, were produced in 1959–60 during a time when Cuatrecasas was also incorporating leaves into his collages and paintings.

Cuatrecasas created another prevalent botanical shape in his paintings, which he called the “thickets,” and these may have been a cross-section or “fingerprint” of the frailejón’s woody columnar stalk. Together, the broad leaves and the spikey stalk are recurring biomorphic shapes that play important roles, often overlaying each other and forming patterns while reveling in color.

Developing Avant-Garde Techniques

Cuatrecasas perfected decalcomania, an uncommon technique — discovered by the Spanish surrealist, Oscar Dominguez [1906–1957] in 1936 — where biomorphic dendritic patterns are created by chance. Invoking José’s documentation of many types of leaf forms, Cuatrecasas likely would draw a large frailejón leaf on a firm paperboard (or another firm material) and then cut it out to create a master plate. He would then paint the face of the plate, and with pigments still wet press the plate firmly onto the surface of the canvas. After rubbing the plate he would then have peeled it away. The transferred image revealed a delightfully unpredictable branching with an intriguing texture. The results vary depending upon the degree of manual pressure applied, the viscosity of the pigment, and the speed with which the plate is pulled off. The pigments typically form dendritic ridges similar to the crystalline tree-like patterns occurring naturally in certain moss agates. Cuatrecasas was certainly aware of the surrealist Max Ernst [1891–1976] who took decalcomania to new heights by creating a fusion of forms that appear to be figures and other natural forms in a kind of organic decay.

However enigmatic was Cuatrecasas’s character, it seems that he felt that his images should be even more mysteriously compelling, and he deepened the secret of his style by employing a mosaic of complex techniques. Beyond his pouring of pigments, the frottage, and the wet-on-wet folding of the canvas he also painted, crumpled, and pressed into service thin plastic sheets as tools to create texture — and even scraped away layers. Finally, subtle layers of glazing in his paintings add a diaphanous depth and bring out color.

Ultimately, Cuatrecasas’s paintings reveal their greatest affinity with the work of another colleague with whom he exhibited in Washington, D.C. — Sam Gilliam. Working 4,000 miles apart and unaware of each other’s latest experiments during the late 1960s–early 1970s, these two artists developed parallel styles independently, suggesting a spiritual zeitgeist, as they employed a brushless wet-on-wet technique with folding, creasing, and frottage. Viewers are inevitably drawn to protracted explorations of their canvases.

A Major Exhibition and a Dénouement

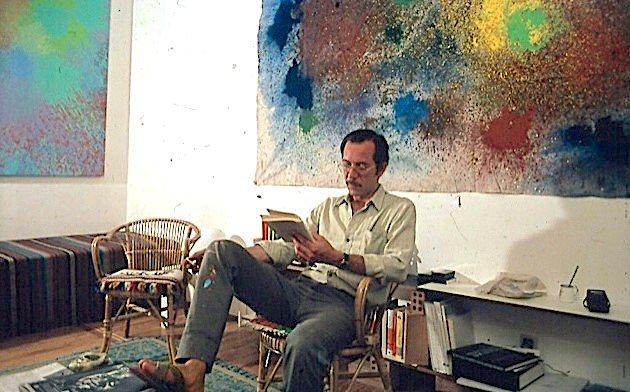

By the mid 1970s a stream of artists, poets, art critics, journalists, and gallerists visited Cuatrecasas’s studio in Torino to view his then quite large body of work. Perhaps the most famous and frequent visitor was the Italian art publisher and collector, Umberto Allemandi, who became a champion of the artist. “His total, obsessive devotion to painting impressed me deeply,” he wrote. “He came preceded by his fame of having left each of his studios, from Washington to Barcelona, choking with canvases.”

Allemandi and others who saw the collection produced in Torino during that seven-year period were profoundly moved and urged Cuatrecasas, albeit unsuccessfully, to exhibit. He wanted nothing to do with galleries or anything that distracted him from his painting. Instead, he remained compulsively focused and prolific, covering the vast floors of the Torino home with hundreds of large canvases from eight to twenty-two feet long. A partial explanation for his recalcitrance could be discovered in his bookcase. Most of the books were concerned with Far Eastern religions and philosophies such as Zen and Taoism. Others were about the occult and psychoanalysis. The titles reveal an introspective personality, a philosopher reticent to explain the origin and meaning of his paintings. He was also frugal in every aspect of his life — except when it came to the quality of his painting materials. Acrylics were a very large part of his budget, and he was very happy that he could buy top quality acrylics in Italy that cost less than those in the United States. Because he lived in Torino, it is most likely that he purchased his acrylics just 75 miles to the east in Milan where the Maimeri family produced their famous Brera brand, respected as among the finest pigments available worldwide. Their pigments are touted for their strength, elasticity, and color-fastness, drying to a permanent egg sheen finish. In fact, he agreed to sell three large canvases to Allemandi only because the transactions allowed him to purchase more pigments.

In 1973 Cuatrecasas returned to America to visit his sister in Syracuse, New York. There he reconnected with James Harithas, then the Director of the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse. When Cuatrecasas showed him photographs of the body of paintings in the Torino series Harithas counted himself among the stunned. Two years later, when he was named the new Director of the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston he invited Cuatrecasas to a solo exhibition intended to travel to other museums. Known as a provocateur, Harithas was hired to bring new energy into Houston’s art scene. “My mission was to bring to Houston first class works by important artists even if those artists were young and lacking recognition. Cuatrecasas’s paintings were beyond the taste of the moment. I showed Julian Schnabel at about the same time, years before he became famous in New York. Turned out that everyone in Houston hated me for it — but I didn’t care.”3

Harithas selected a collection of the large paintings and in 1976 had them shipped to the museum. Cuatrecasas would soon return to Houston to work with a team in unrolling the large canvases and fixing them upon their stretchers. But on June 15th — just two weeks before the exhibition was to open — Houston was suddenly hit with a tropical storm that dumped more than ten inches of rain in six hours. It was the worst flooding disaster in the city’s history, drowning eight people. Eight feet of water flooded the museum’s basement. Paintings by Josef Albers, Max Ernst, and Norman Bluhm and many others were destroyed. So were about 200 canvases and as many works on paper by Cuatrecasas. Naturally, the exhibition was cancelled.3 Cuatrecasas was understandably quite distraught and his despondency bordered on depression. Not only had he failed to recover proper compensation from the insurance companies but he had lost a major exhibition that would have reintroduced him to the art world. Harithas later observed, “Cuatrecasas would have become famous had he only gone to New York. I told him so, but he just seemed to shrug it off.”

Instead, Cuatrecasas returned to his aunt’s apartment in Barcelona as she had retired and sold the Torino villa. His brother recalled, “Within a few months, amazingly, his artistic restlessness and drive to paint again raised his spirits enough to lead him to take some bold action. With modest financial help from the family he bought a very large 200-year old stone farmhouse just outside of Barcelona. He worked immediately with rare zest with an architect and a builder to design exactly what he wanted: an enormous live-in studio where he could resume his life’s work. This was his new dream. The renovation began and moved along well for two years. He visited and managed the progress daily, driving his beloved old yellow Ford Pinto wagon he had shipped from Washington, D.C. Progress began to slow down in the third year of this complex process because of costs, construction complexities, and the frequent absence of the builder. Gil persisted with continual phone calls and visits, but to no avail. Finally, after nearly four years of increasing frustrations, all work stopped and Gil had little choice but to give up. The task failed. He just abandoned the farmhouse, never to see it again. His Pinto sat untouched in a garage for ten years. His last dream was shattered. This was a calamity that may have been his major career-ending event. He was now forever destined not to have a proper studio again.”4

From this point his creative energy progressively diminished. This was his dénouement. Mired in understandable despondence, and aggravated by his living circumstances, it seemed as if he heard the fates decree that his life’s work in painting would never re-emerge. But his aunt, Montse, would not give up. In 1979 she convinced him to hold a solo exhibition at the government’s well-known Galerías Syra in Antonio Gaudí’s iconic Casa Battló in Barcelona. Critics lauded the Torino paintings, citing their “chromatic exuberance,” and “absolute control over color.” Surprisingly, one even got him to speak of his having been inspired by the linearity and shapes of the Gothic wall paintings in the National Art Museum of Catalonia in Barcelona depicting the conquest of Majorca. Despite the accolades, Cuatrecasas only briefly attended the opening. Again, he showed no interest in selling.

Cuatrecasas not only ignored the substantive critical praise for his work, but he suffered a series of devastating setbacks during the last twenty-five years of his life that forever prevented his return to painting. First, he battled alcoholism, ultimately achieving sobriety. But he was a chain smoker, too, and in declining health he suffered from tuberculosis. Just days after his father passed away in Washington, so did Montse. Having lost his Guardian Angel, he also had to vacate her apartment. He moved to a small apartment that his parents had purchased many years earlier but he had no studio space at all. His brother Pedro wrote, “He remained despondent in his new apartment, unable to paint in such a restricted space, although he often wished and visualized painting again. That inner fervor was still there.” It was as if the circumstances imposed upon him dictated that that his life’s work in painting had become a chapter that had truly ended.

Finally, his last ten years saw him fighting the prostatic cancer that ended his life. But just before he passed, Pedro was going through papers in his brother’s Barcelona apartment when to his surprise he discovered a stack of unpaid bills from Security Storage in Washington, D.C. threatening to dispose of the contents in two rooms. Unknown to the family, Cuatrecasas had since about 1974 made several shipments of about 400 hundred large canvases carefully rolled up in heavy-duty kraft tubes, likely in anticipation of more exhibitions following Houston. “Like most details of Gil’s reclusive life, the existence of the Torino paintings was a total surprise. But there they were — rolled up in batches of two to six canvases that weighed up to 100 pounds per roll. Some canvases measured 22 feet long, and none had been displayed in the United States.”5

Conclusion

Art forensics has helped to unravel the mystery of Cuatrecasas’s technique. Stylistic analysis has shown the maturation of his vision. And art history will place him as a virtuoso of color. But unraveling the mystery of why such a prolific master would stop at the peak of his powers is far more complex. He was both an intellectual and a spiritualist who revealed a depth of character. Earning money from his art was never a motivation and he harbored a disdain for material things. He was reclusive, too, avoiding social occasions with people unknown to him. His sister, Teresa, often remarked that he should have lived in a monastery.

The revelation of Cuatrecasas’s chapter in the history of late 20th century painting is not only long overdue but brings together the artistic spirits of both America and Spain. In this process of discovery one gains a historical perspective that places him firmly in the ranks among those few brilliant colorists of his generation. Here was an artist who was never motivated to garner money or fame from his art. But he made this discovery possible only because forty years ago he cared so deeply about preserving his extraordinary collection of paintings.

Peter Hastings Falk

2016

Footnotes

1 All quotes from James Harithas are from the author’s telephone interview with him on 20 August 2014.

2 Albers’s teachings were later published in in 1963 in his landmark Interaction of Color.

3 “CAM KO’d” (Texas Monthly, Aug, 1976, p.20)

4 All quotes from Cuatrecasas, Pedro. Gil Cuatrecasas, The Torino Collection, 1970-1976, An Undiscovered Treasure (San Diego: privately published, 2013)

5 Gelt, Jessica. “Brother rescues 400 lost works from storage unit by late Spanish artist Gil Cuatrecasas,” (Los Angeles Times, Arts & Culture section, 18 Feb 2016, Sec. E, p.1)