“The future gets to know what I can see

and that is the difference between you and me.”

The Shack in the Jungle

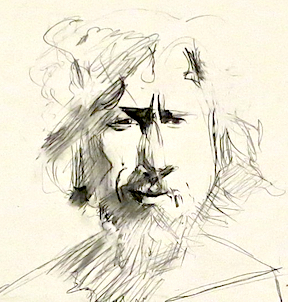

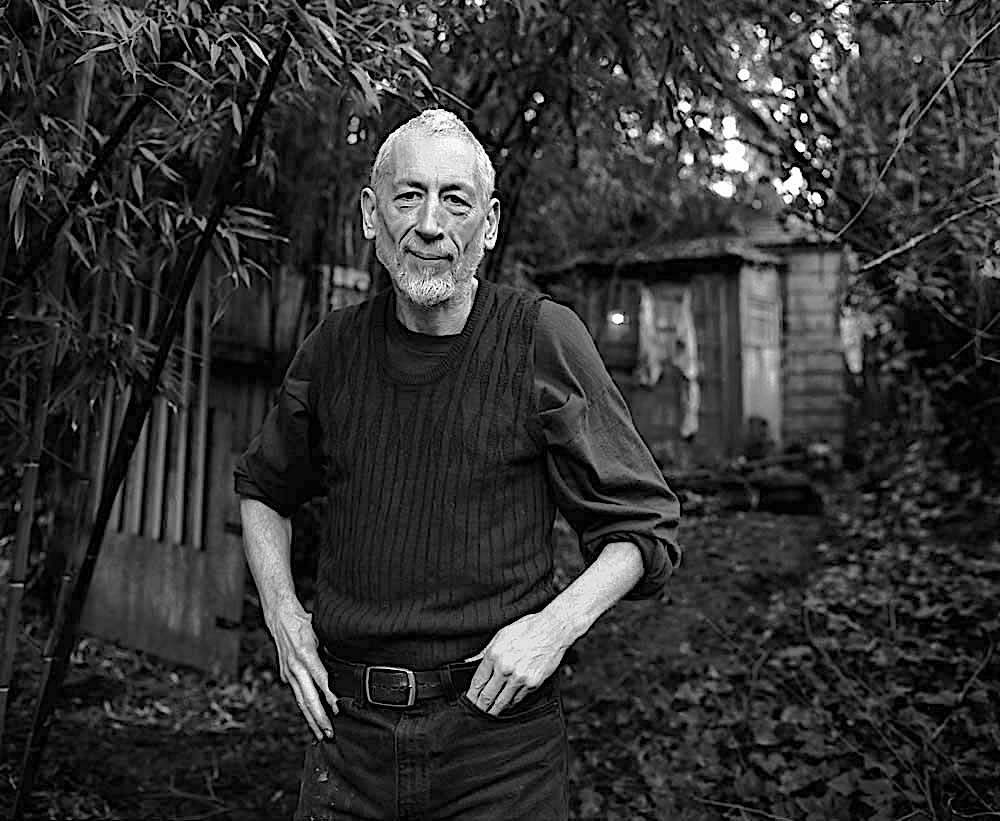

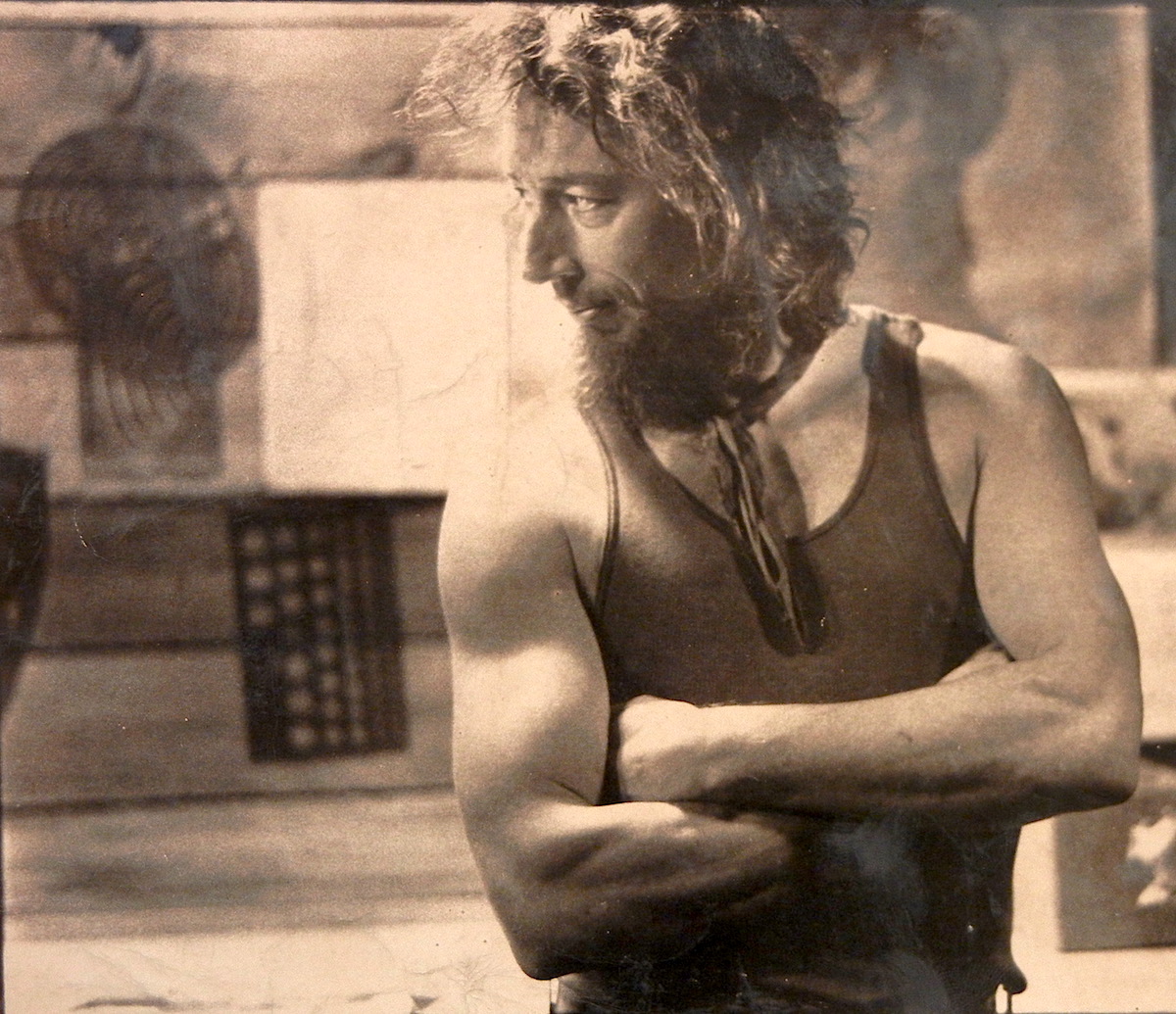

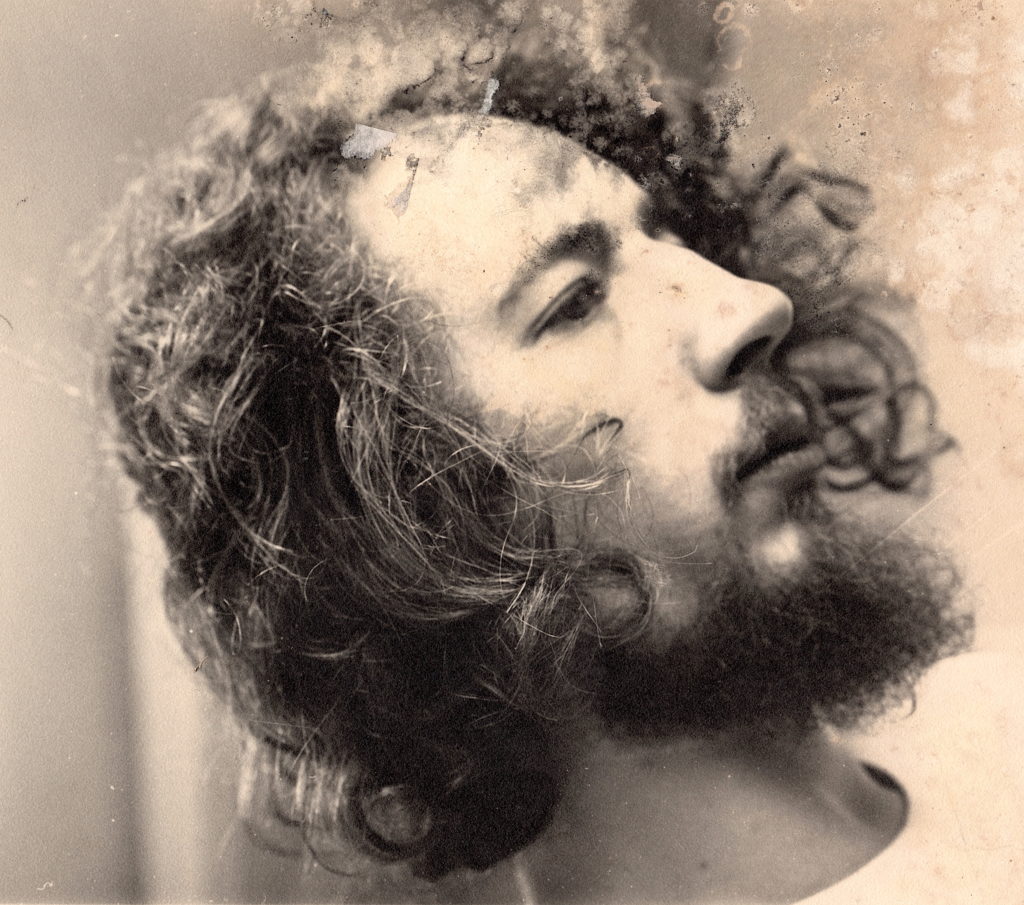

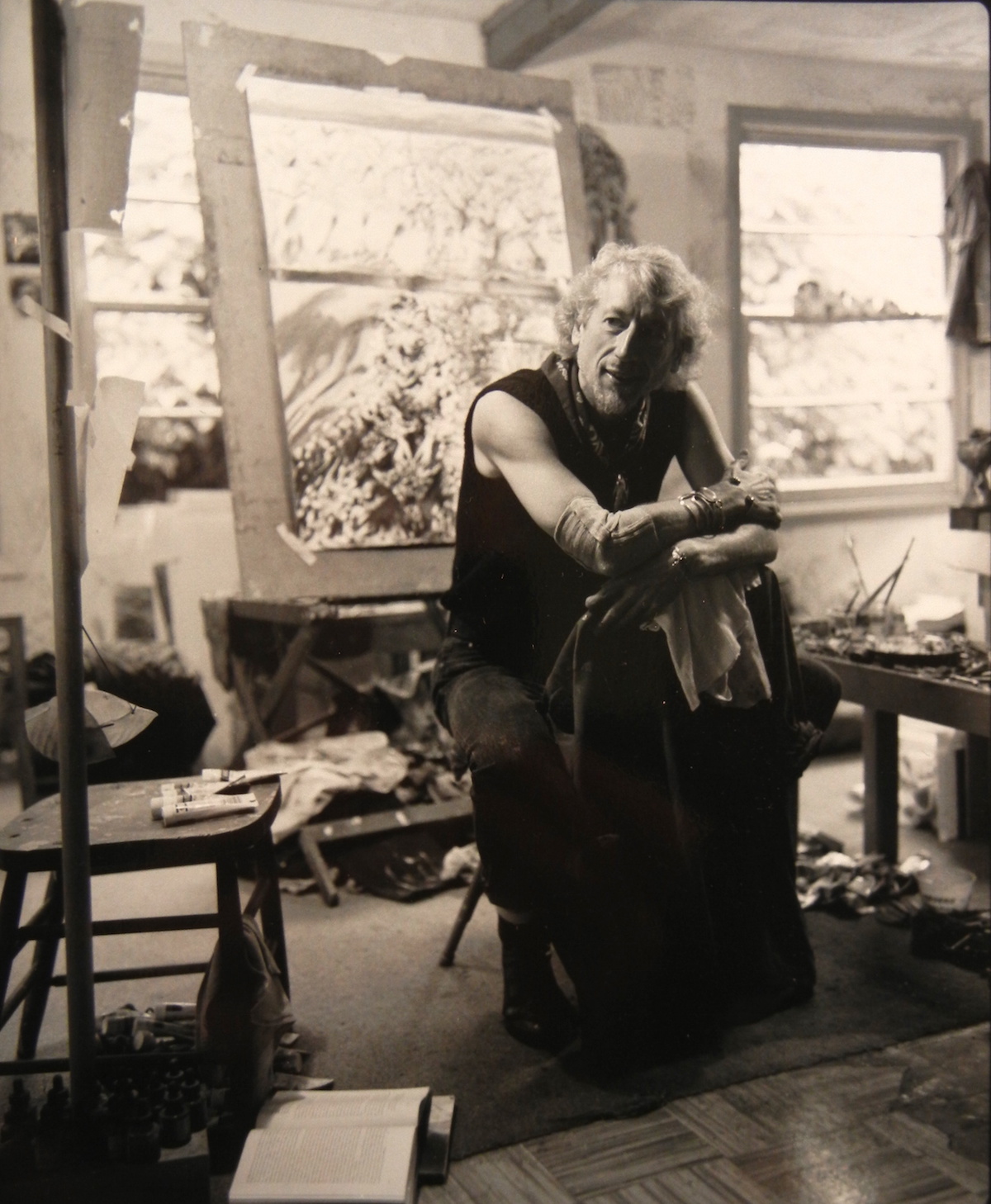

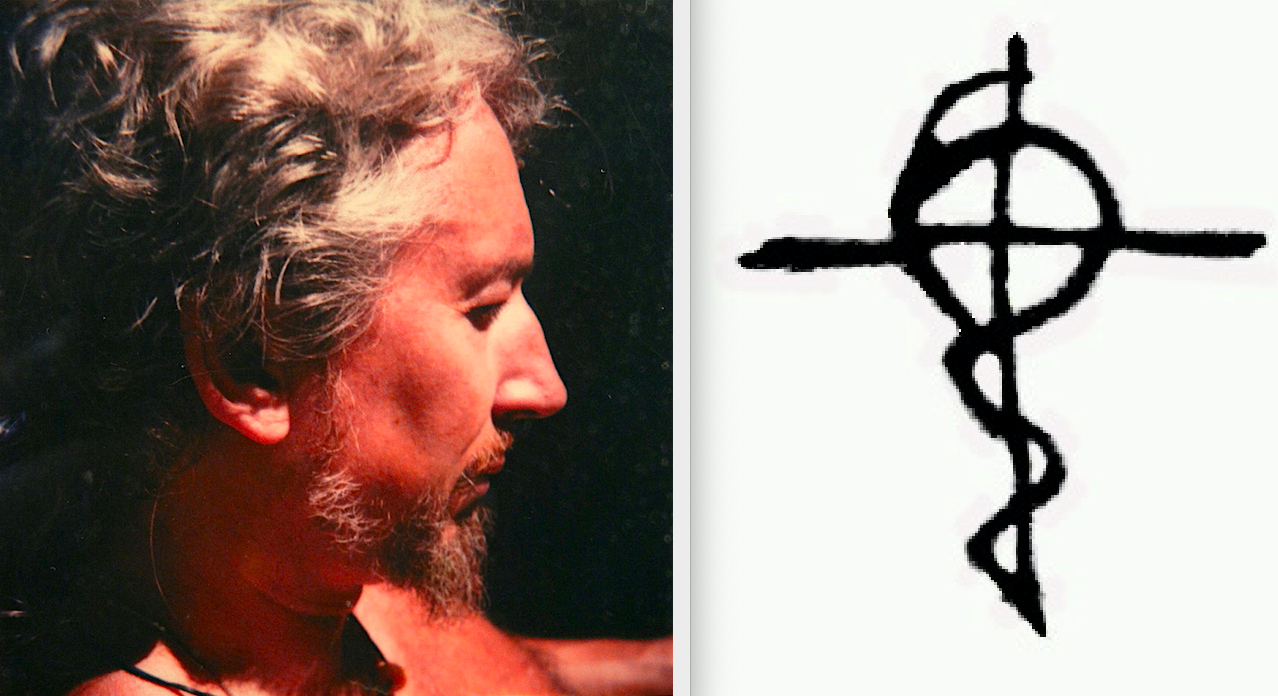

Tom Blodgett’s long graying hair flowed like a lion’s mane framing his rugged good looks. His eyes were intense and penetrating. Even as he aged, his six-foot one-inch frame remained athletic and sinuous. But to most he appeared to be a lion with a thorn in his paw, hurt and angry. He was viewed as the quintessential reclusive artist — an irascible character at odds with the world.

His dilapidated cottage was perched in the south hills of Eugene, Oregon. He called it “the shack in the jungle.” There was no running water. His toilet was a pit he had dug outside and into which he would regularly shovel ash. The furnace was often broken so his only dependable source of heat came from a large fireplace. The shack was engulfed in an evergreen jungle of bamboo rising forty feet high, a barricade made even more dense by blackberry brambles half as tall — rendering it completely hidden from view. Decades earlier, the big trunk of a dead tree had come to gradually lean against the house just above a window he always kept open. He called the tree trunk “the bridge” because it served as a convenient and busy opening for the comings and goings of squirrels, raccoons, opossums, and birds whose daily routine was to feast on nuts the artist had left for them in dishes around his studio. Deer would also frequently come calling. The cats — he had seven at one point — were omnipresent sentinels.

Another tree — a cottonwood at least one hundred feet tall — hung precariously over the small attached garage. Because the artist had no car, and instead walked everywhere, he had converted the garage into a studio. He lived with the fear that a particularly strong storm could bring the big cottonwood crashing down through his shack. There was no basement, and the cottage’s wooden floor was set close to the ground. This was a fortunate feature in the event one of his students fell through one of the holes in the floor. But the gaping hole in his roof was another matter. On a clear night one could even see the stars through it. But Eugene is notorious for its temperate rain forest climate with more than fifty inches of rain annually. When rainwater began dripping from that hole it would eventually form a rivulet under the floorboards that wound its way under his cottage and down the slope. During the heaviest extended downpours that rivulet could suddenly become a surge flowing over the floorboards and pushing open the front door.

Within this bohemian natural environment the artist quietly created an extraordinary body of work — large drawing-paintings — that stand out among the most original and compelling in the history of American art during the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st. In 2000 at age sixty he reflected, “I have to realize the transcendence of this kind of place, this kind of aloneness, this kind of being left more than alone. More than I was alone in the 1960s or 1970s or even the 1980s. This new alone — That is more than alone. That is being left. Left. And I’m going to transcend it.” Yet when he died of cancer in 2012 he was virtually unknown, frustrated that the deus ex machina that he always felt would somehow arrive to bring him national recognition had never shown up.

From Visionary Teacher to Recluse

Tom Blodgett was an artist of extraordinary drawing skills and vision whose concepts of figure, landscape, and space were steeped in mysticism and surrealism. And this is the tricky part for art historians. Whenever we are confronted with artwork that is difficult to categorize we conveniently referred to it as “idiosyncratic.” Such works are outside most comfort zones, even for academics. Neither illustrative nor abstract, they draw upon a primal unconsciousness. Immersed in mysticism, Blodgett felt his works far surpassed Morris Graves and the Northwest School of Visionary Art. But today the very word “visionary” evokes New Age artists producing a plethora of psychedelic illustration based upon Far Eastern Tantric Buddhism. Blodgett’s transformative figurativism could also easily be placed with the Magic Realism of Ivan Albright, who focused on the body’s decay, or with the New Romanticism of Pavel Tchelitchew, who rendered the human body without its skin. However, Blodgett was less concerned with transforming how things looked in this world than with expressing images that had been tapped from his unconscious, his dreams, and his demons. Spiritually he was more aligned with the mysticism of Mondrian, Munch, and Kandinsky — whose paths to the unconscious influenced Marsden Hartley, Gordon Onslow-Ford, and Jackson Pollock. And the boldness of his approach is closer to the intense surrealism-expressionism of Schiele, Soutine, and Kokoshka. He felt most closely related to van Gogh — pschologically tortured and artistically rejected but steadfastly pursuing his art. He also felt a strong spiritual kinship with other great artists working outside the mainstream, including Goya, Rembrandt, Breughel, El Greco, and William Blake.

For nearly ten years Blodgett taught at a local college where his classes were always oversubscribed. Despite quitting in 1976 over a political dispute with faculty his reputation as a brilliant, charismatic (and alcoholic) teacher was so widespread that many students followed him to his shack for private teaching. They were as captivated by his philosophy of art as they were his teaching methods. He was a strict and highly confident master, often proclaiming that he could draw from a deeper place and create more compelling art than any artist in the country. For every session, he tacked up his philosophical dictums for his students. “We are responsible for Reality. We don’t make it. It makes us. We make Art, and artwork teaches us what a responsibility Reality truly is.” Intolerant of slavish copyists, he exhorted them to “grab greatness out of the air like a juggler.” Ultimately, he would become frustrated over his students’ inabilities to tap their unconscious, and he would drive most of them away.

Not only did Blodgett leave behind a very large art collection, but also any historian would be hard pressed to find another artist who was equally prolific a writer. His archive includes thousands of hand-written pages — all in pencil — including poetry, short stories, stage plays, and novels. He frequently expressed his frustration with lack of critical recognition, which brewed into a resentment he carried throughout his life, and frequently referred to himself as “the van Gogh in Oregon.” Even when he began writing in earnest in his twenties he expressed this anger, exclaiming, “I write for you whom I hate and whom I hope never thinks of me — never. And if only one of you never thinks of me and will never read this, it’s for you whom I write. I mean this.”

Blodgett’s few local exhibitions predictably left most Eugenians scratching their heads in confusion. Others were downright frightened, as if they had just emerged from a Stephen King horror movie like “The Shining.” Blodgett refused to abide by anyone in whom he detected a lack of ability to see and be moved by the fact that he was presenting “real art.” He blamed Eugenians — particularly those mixing politics with the city’s cultural life — referring to them as the evil philistines of an artless city bent on keeping the crazy artist isolated in the hills.

A Trauma in Childhood

Traumatic events in early childhood can bring together an irrevocable fusion of anger and bitter isolation. When they are wrought upon an artistic genius the suffering can yield surreal results. Dalí, Magritte, Tanguy, Picabia, and Picasso are among the masters who as youths were traumatized by the death of a parent or sibling and they rebounded with uniquely creative visions. But for Blodgett death of another kind of suffering conspired and boiled over when he was a little boy.

Thomas Lowell Blodgett [1940–2012] was born on August 29, 1940, in Oregon City, the youngest of three boys. Their father was a clerk at the Post Office and their mother was a devout Baptist and dutiful homemaker. But since Tom was younger than his brothers by fourteen and sixteen years he always felt that his birth was a late “mistake.” Indeed, age was just one issue when the oldest brother, Jutz, returned from Germany in 1947, two years after the surrender. Jutz was an angry young man who had missed the battles and instead served with the U.S. Army of the Occupation. He was open about his hatred of the Germans, and after becoming embroiled in an argument with a German citizen, Jutz shot and killed him. Jutz returned to Oregon City a changed man. Most assumed he had “combat fatigue” — better known since the 1980s as PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder). But he had always harbored problems of another kind. Once back home, the 23-year-old’s anger continued to be unleashed on his 7-year-old brother, Tom, who later wrote that he was repeatedly victimized by “a monster” that locked him in the basement, tormented and beat him, and “gave me my first concussion.” The middle brother, Mo, never knew about the abuse because no sooner had he returned from serving in the war in the Pacific theater than he found a job in New Mexico. Tom’s trauma remained a vicious secret apparently unknown to his parents. His attempts at survival included finding various hiding places in the house, including the laundry chute. In addition, after his mother’s death Blodgett found a tormenting surprise. “I read my mother’s diary and I wonder, when do the secrets stop?!” he wrote, …the wrong someone might get ahold of her diary and see the truth!” Unfortunately, after Blodgett’s death in 2012 the diaries from before 1950 went missing.

Fortunately for Tom, Jutz was eventually arrested for armed robbery and incarcerated in the state prison. But by that time Tom had developed what doctors later surmised was either a rare virus that caused incessant vomiting or a rare anorexia-related eating disorder. In 1950, after a prolonged period without any food whatsoever, the starving ten-year-old was rushed to the children’s hospital in Portland. As he lay in the hospital bed he could feel the life slipping away from his body. “I just remember blacking out. The tunnel, the light, the train, all the things people remember when they die. The doctor saying ‘He’s dying.’ My mother crying. And I remember coming back to life.”

Blodgett would later write that his illness was the most important turning point in his life because he experienced a kind of rebirth. Recuperating slowly at home, he gradually accepted the nourishment his body needed. At age 10 he missed more than a year of school and turned his bedroom into a sacrosanct place where he lived “a very secret life.” He had a voracious appetite for drawing — he frequently stated that he began when he was three and a half — as well as being immersed in reading and inventing games and fantasies. At sixty he would reflect, “I think that it is possible that the artist/psycho split could be real. Because if I look back honestly at myself as a kid I was a perfect symptomatically psychopathic type — torture, fire etc. — but I came out this guy.” Drawing became more than a boy’s passion. “I remember people asking me what I wanted to be. I went on for a while. I never said artist. Asking a young artist what he wants to be is like asking a baby whale what it wants to be.”

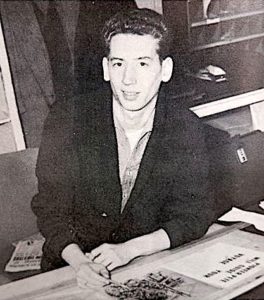

Back in school, and with Jutz out of the picture, Tom also pursued his love of basketball and baseball. He was a stand-out pitcher in baseball and his father wanted him to become a professional. Tom also acted in theatre and was well known by everyone as an artist. One of his close friends in high school was Walt Curtis, now the well-known street poet called “the Salmon Poet” and “the Unofficial Poet-Laureate of Portland.” Curtis stressed to this writer that learning clues to Blodgett’s character starts with an understanding of the environment in which they both grew up in Oregon City. “It was a grim and gray mill town filled with rednecks — a blue collar football town with no patience for artistic types. In the 1940s and 50s it wasn’t so easy to communicate in a sensitive way. I was already writing poetry in high school. That was dangerous enough. And I had homoerotic leanings. At one point I just wanted to commit suicide. So, it was natural to gravitate to other artistic souls. That is how I met Tom. We recognized at a psychic level — at an intuitive level — that we were different. How many people could Tom really relate to in a town like that?”

Emergence of the Painter Poet

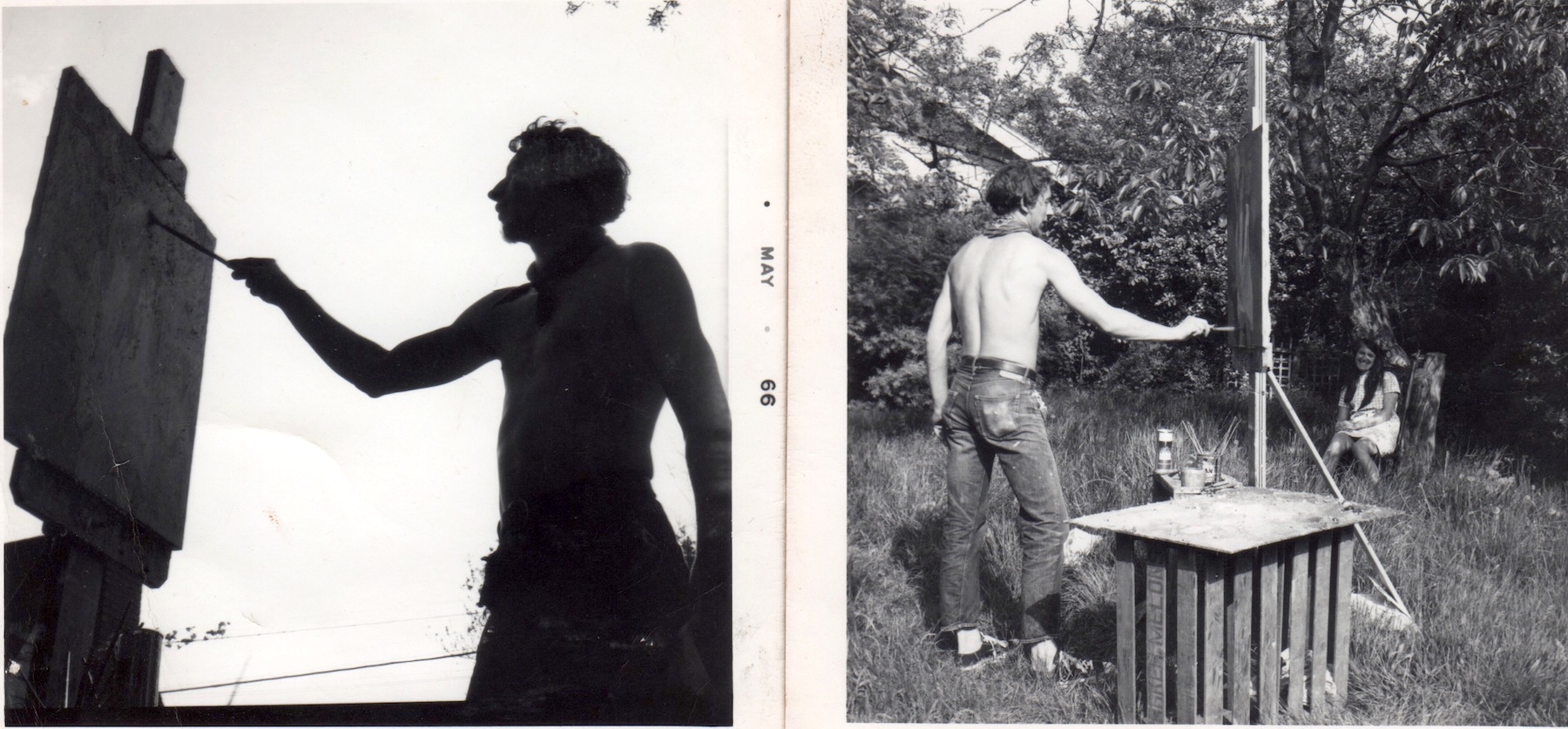

Blodgett was a studio art major at Lewis & Clark College. Entering in 1958 during the peak years of the Beat Generation, and inspired by Walt Curtis, he took courses in poetry and creative writing. In 1962, during his senior year, the student collective, simply called Magazine, published one of his poems. After college he continued to flirt with acting, performing in “The Caretaker” at Portland’s Civic Theater Blue Room.

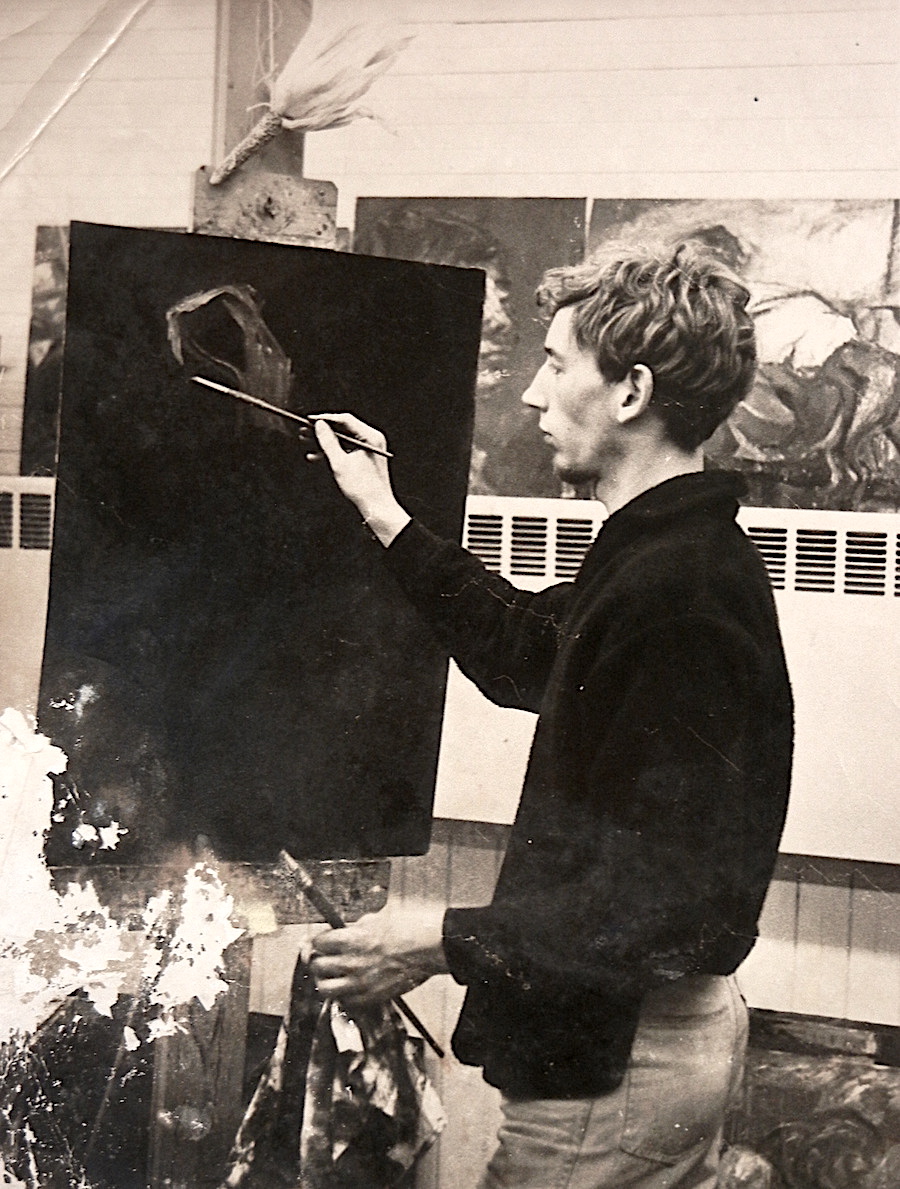

In 1964 Blodgett enrolled at the University of Oregon to pursue his Master of Fine Arts degree. His mentor was an artist-philosopher, Jack Wilkinson [1913–1974], arguably the most influential art professor in the university’s history. Wilkinson’s theories for analyzing visual experience had a profound and lasting impact upon Blodgett. His approach to teaching asked the artist to address every problem by first sketching a quadrant grid to break down the issue into its most basic opposing means and extremes described in the four squares. For example, a cause would be in a box across from the box for the agent to which it related but diagonally opposite the box for its effect; further, a process that related to its effect but would be diagonally opposite its agent. It was heady thinking, and Blodgett sometimes found himself deeply immersed in discussion with Wilkinson from 8:00 a.m. in the morning until 8:00 p.m. at night exploring phenomenon, perception, process, and expression. Throughout Blodgett’s life he frequently interjected sketches of quadrants in his notebooks as part of his examination of any issue.

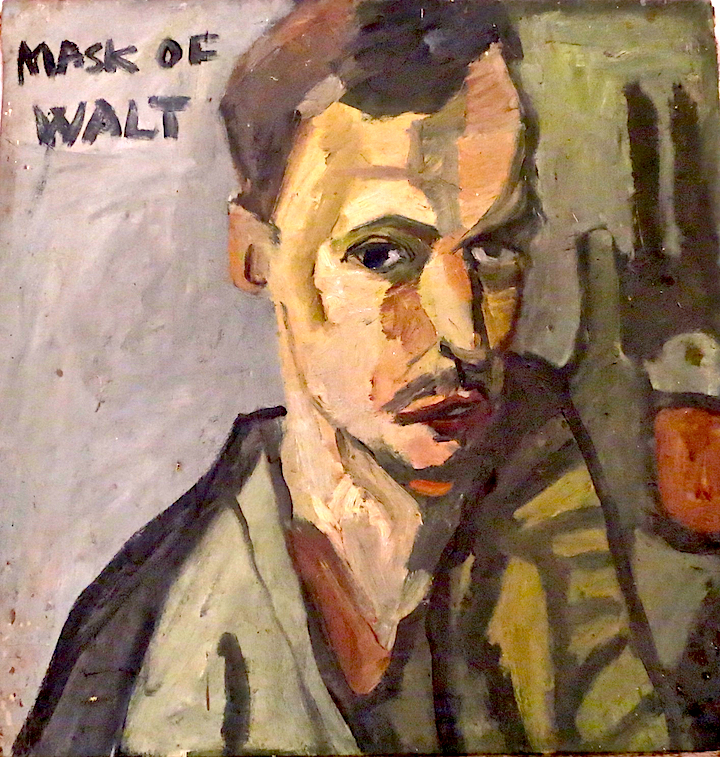

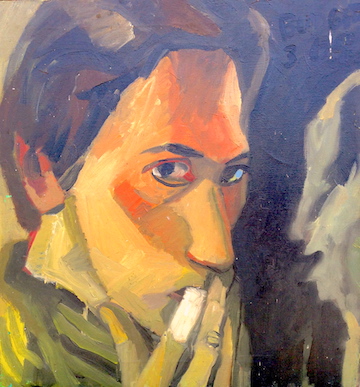

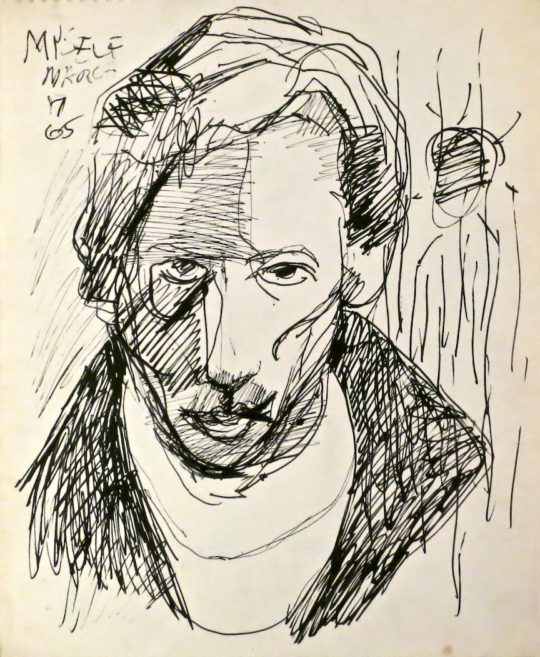

A close relationship was forged between master and student and Blodgett became Wilkinson’s teaching assistant, an inspired disciple who was fiercely passionate about sharing this philosophy of art with students. He rented a cottage near the university where he pursued his own vision, constantly drawing and painting landscapes, figural studies, and portraits — many of them defying comfortable interpretation and pushing into the surreal. But during this post-college period Blodgett had to solve two perceived problems. First, in 1965 he desperately wanted to get out of the marriage into which he had hastily entered with Marty when he was back in college. This was the first of his four marriages during which he would carry on a string of affairs — some with women who became important muses that would last for several years. However, despite his verbal abuse of Marty, calculated to end the relationship, she simply refused to leave him. But he was confident that his dramatic skills were potent enough to unleash a shocking scene that would dislodge her for good. During one candlelight dinner he told her that this would be the last time he would demand that she leave — to which she again refused — whereupon Blodgett replied by calmly laying his left hand flat on the wooden dining table, and quickly grabbing a nearby prop — a two-by-four piece of lumber — and shockingly smashed his left index finger. Next, wielding a hatchet, he actually chopped off the top part of his finger. Finally, with his finger gushing blood he placed it over the candle flame to cauterize it. Marty was aghast and ran from the house, never to return. Just as van Gogh painted his self-portrait after cutting off his ear, Blodgett painted his self-portrait after cutting off his finger.

Blodgett’s second perceived problem was the Vietnam War, which was in full sway when he received a draft notice in 1966. One of his artist friends, Jay Lindsay, had just been convicted of draft evasion and would spend the next two years in prison. This was a time when widespread protests against the war were still several years away from erupting across the nation. Blodgett just wanted to be an artist. So, when he appeared before the draft board he was drunk and disheveled. His long hair was flaring wildly, and with his eyes wide and glaring he intentionally spewed a surreal stream of consciousness. The board was shocked but suspicious. A psychiatric evaluation was ordered. Once again he summoned his skills as an impersonator, exclaiming that he wanted to sign up for the Rangers so he could kill, eviscerate, and drink blood. He had prepared so well for his performance that the two attending psychologists could not make a clear evaluation. His status was officially listed as “1-H,” a vague category declaring him “not currently subject to processing for induction.”

After receiving his Master of Fine Arts in 1964, Blodgett took teaching jobs at the local Lane Community College as well as at Oregon State University about forty miles north of Eugene in Corvallis. He quickly became recognized as a dynamic teacher. Even though he had remarried in 1969 he was already estranged from his wife when in 1971 he fell in love with a student in Corvallis. During the next two years Natasa Sotiropoulos would become his first significant muse. Now an accomplished painter of Manhattan street scenes and portraits, Natasa recently explained to this writer that “Tom was deeply into mysticism and it gave life to his work — and in his understanding of how to create visual textures he could draw miracles.” She also noted that students who became groupies deified him. “He could cast a spell on someone,” she observed, “especially young girls…effortlessly.”

Harold Hoy, a sculptor and one of Blodgett’s fellow teachers at Lane, pronounced, “Tom was the best art instructor that Lane ever had. He was so magnetic; he drew people in. He taught from a Renaissance perspective, reading poetry in class and talking about great writers.” Nevertheless, new students were typically nervous about taking a Blodgett class. One student, when asking another professor about the prospect, received the curt response, “Be careful of Blodgett…he’s serious.” This was because “It became well known that you needed a thick skin to be able to deal with him. He prided himself in discerning people’s weaknesses.” Indeed, Blodgett’s students usually cited him as the most dramatic and difficult person they had ever met. “You can learn technique from any good artist but Tom’s lessons in drawing were more about those things that forced you to look deeply inward,” said Hoy.

One of Blodgett’s most accomplished students was the sculptor, John Fisher, who would later spend twenty years carving marble in Pietrasanta, Italy. Blodgett inspired Fisher’s direct approach to the giant marble blocks, without any preliminary sketches. “He showed me the process of pulling the image out of the abstract. His concept was that ideas that come from our conscious brain are superficial and stereotypical. The idea that came from the process, that was born from the process, sprung from our inner core…Tom had shown me the direction my life would take,” says Fisher. “When you really go out on a limb, when you have no solutions, when you are about to fail, that is when adrenaline kicks in and you pull out the creative act.”

The Seclusion of a Genius

While teaching at Lane Community College, Blodgett filled several notebooks with his treatise about overhauling the way art had been taught for generations. In 1976, some faculty had even nominated him to be chairman of the art department — even though the current chairman was not going anywhere. Some faculty friends later saw the nomination as a mean trick and it resulted in Blodgett abruptly quitting the faculty on principle. His bitterness never dissipated and instead led to a reclusiveness that would last for the rest of his life. Nevertheless, he felt strongly about imparting his teaching of art and philosophy. The significant void left by his quitting would not last long. His notoriety grew and for the next thirty years he attracted students to his shack for private drawing workshops. “No question, he was extremely charismatic, attractive, amazing and intimidating,” commented one of Blodgett’s nieces who, like many other family members, the artist would ultimately drive away. “It was like spending time with Mick Jagger, Martin Scorsese, Gandhi, Socrates, Nelson Mandela, and van Gogh all at the same time. People were mesmerized by him.”

Another problem — far more challenging to overcome — was alcoholism. In graduate school Blodgett realized the coincidence that Wilkinson, too, was stuck in the same alcohol quagmire. Even with Blodgett’s male artist friends their common interest was drugs, alcohol, and women. Well aware of his problem, he wrote essays about drinking, such as his “The Art of the Sober Drunk, A Fantasy Essay” from 1976. He explained that “A drunk will hate what they love. A sober drunk will love what they hate.” Alcohol — omnipresent in his life since the 1960s — was finally shut off when his friends carried out an intervention in 1986. Blodgett suffered through the ordeal of a detox program and joined Alcoholics Anonymous. He resented most of the local AA members for implying that “being an artist” was in part to blame for his drinking. On the contrary, he realized that he needed to take control of his demon in order to reach new creative levels.

Now sober, Blodgett’s artistic drive became supercharged, and he dived even deeper into the unconscious. He also continued to write every day, filling notebook after notebook with poetry and his philosophy on art, interjecting an acerbic humor that skewered American art, music, politics, and the media. He also wrote numerous short stories, theatrical plays, screenplays, and even several novels — typically murder mysteries involving artists or westerns. A voracious reader since childhood, he provided intelligent opinions on nearly every subject, hoping that some day his writings would be discovered and appreciated. He expounded upon on the styles and movements of artists and musicians throughout history and was as insightful in explaining why certain artists were true masters as he was in lancing others with his sardonic wit.

“I’m too good at what I do,” he wrote, as he disparaged the work of his contemporaries. “I ruin their game as soon as I walk in the door — that’s okay, I like it. I went all the way and no one I know did that. Hell, I know artists in New York who fancy themselves me and they copy others’ work and sell it! Everything is derivative of Europe, basically, and worthless. Pollock saw that. So did Seurat, interestingly enough. And I figured it out. So, what I’m doing has the same standards as Velasquez and yet it’s based on nothing that he or any of those cats came from. But no one is going to announce that in this city.”

In his poetry, Blodgett would often assign series titles such as “Poem in Eulogy to Americans” (1969) and “A Poem for America, No.1” (2001). The poems often appear as couplets, as haiku, or as quatrains but just as often his poems would be many pages long. He often alerted the reader that these works were from the Journal of a Loser and that they were about to read a “Fake Poem,” “Anti-Poetry,” or “Fake Haiku.” His titles were often long and colorful, such as “LSD, Whiskey, Grass, Beer, and Insect Dreams, Sleeping on the Floor Blues.” Street poets inspired him such as his friend Walt Curtis, and especially Charles Bukowski — also an alcoholic, who in 1986 was called the “laureate of American lowlife” by Time magazine. Blodgett made frequent reference to Bukowski and Curtis in his writings. Those references also appear in his drawings, such as in his work “Love Is a Dog from Hell” — an homage to Bukowskis’ collection of poems of the same title from 1977.

A Unique Vision

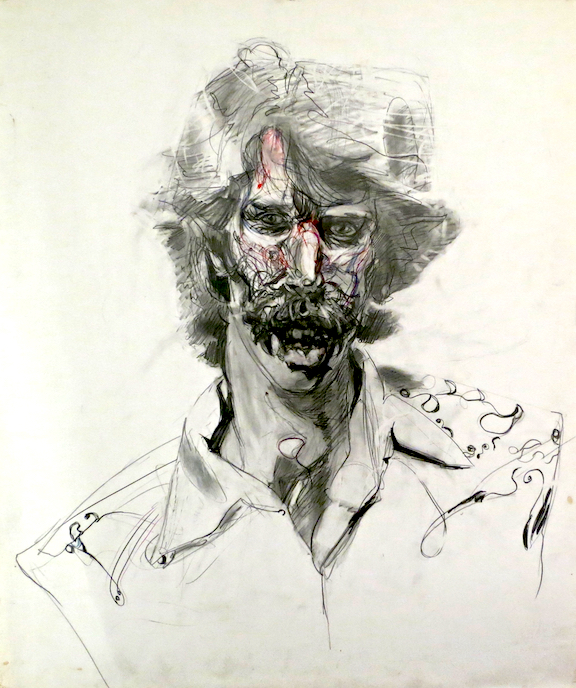

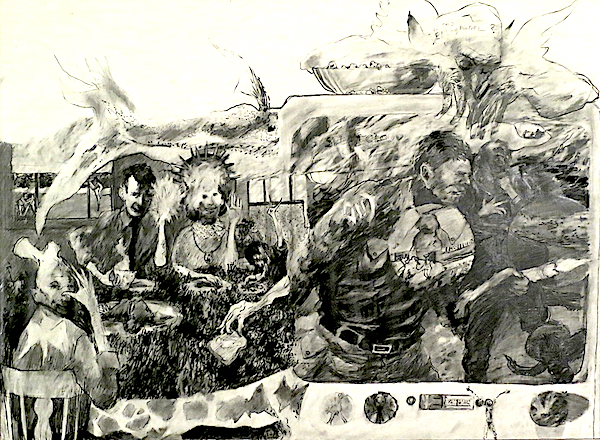

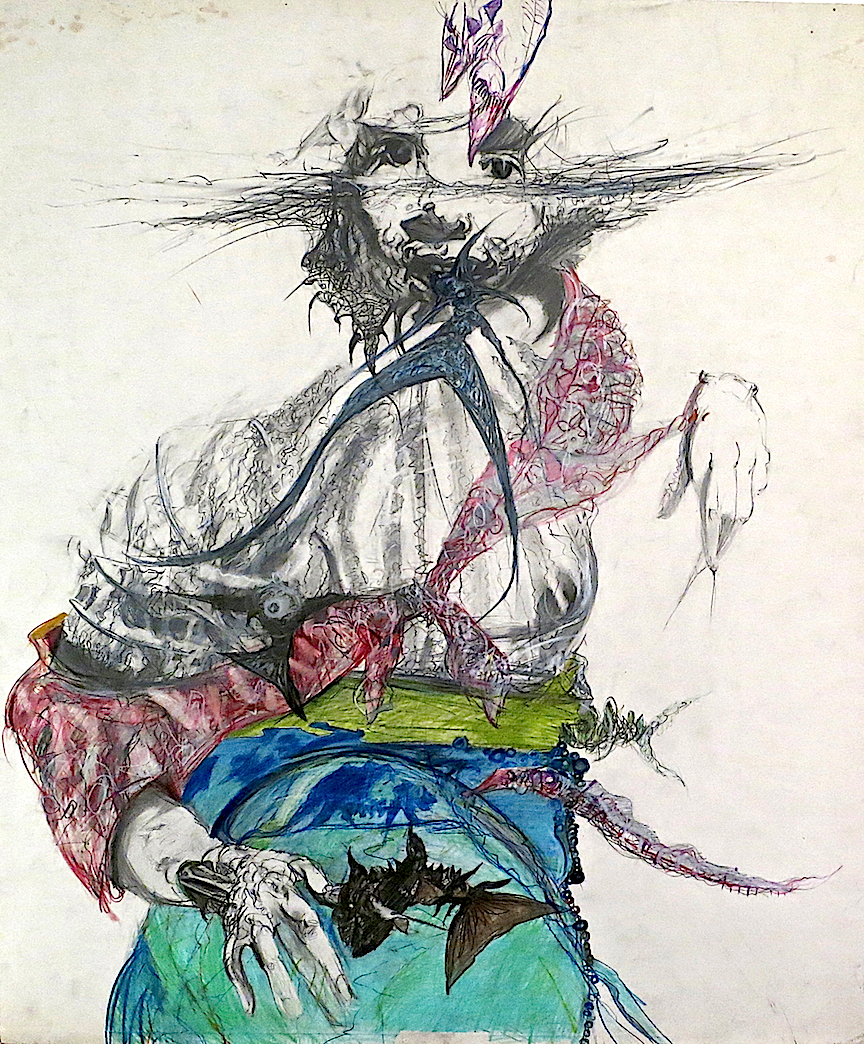

Blodgett’s vision defies categorization. He was so fiercely independent that he would have rejected the stylistic labels of either magic realism or surrealism as misnomers. The Magic Realists were those American painters (such as Ivan Albright, Paul Cadmus, and George Tooker) who during the 1940s and 1950s created paintings that reflect a mysterious and sometimes eerie realism. Blodgett was well aware of their work and he was certainly as far outside the mainstream of American art as was Ivan Albright [1897-1983]. In 1943 Albright won fame when his portrait for MGM’s The Picture of Dorian Gray shocked audiences across America. His style of necrotic portraiture, born of a morbid vision and expressed in an obsessively detailed style, resulted in many haunting homages to the inevitable course of age and decay. Blodgett knew that he, too, was an outsider and he admired Albright’s unique style. Blodgett’s numerous large portrait drawings from the 1970s and 1980s seem to empathize with Albright’s existential angst but they push deeper into the surreal. “Blodgett felt he could capture a person’s thoughts,” said Jay Lindsay. “He claimed to have x-ray vision and the visual acuity of a bird of prey.” He approached every piece of paper and every canvas with the intent of releasing from it a latent image. Recalling Michelangelo’s inspiration when contemplating blocks of marble, Blodgett often referred to the process of painting and drawing as “carving.” He sometimes signed his notes “Carverman.” “There is an absolute logic to the weave of every piece of paper,” Blodgett declared. Working within that weave he revealed himself as a virtuoso who developed a complex drawing technique, unique for its power of erasure balanced with an application of graphite that alternated between rich dense layers and diaphanous veils. The result is an extraordinary series of portraits — unmatched in American art history — that appear to capture his sitters in the moment of transition when they were being revealed as otherworldly beings. In this regard Blodgett was more drawn to the Surrealists in their quest to express psychological truths recovered from our unconscious realities.

Blodgett was also well aware of Pavel Tchelitchew [1898–1957], the Russian-born American Surrealist whose drawings were exhibited in 1930 at the then new Museum of Modern Art. By that time Tchelitchew was making use of perspective distortion and multiple images, later best exemplified by one of his most significant paintings, Hide and Seek (1940–42) in MoMA’s collection. He continued to develop his interest in metamorphic forms and became especially known for his surrealist renderings of the human body without its skin — appearing to many observers as electrified anatomical studies. One of Blodgett’s college notebooks from 1959 contained a clipping from Life magazine of Tchelitchew’s Phenomena. The caption read, “He shows the ugliness of beauty, and the beauty of ugliness.” Like his Surrealist counterparts in Europe, Tchelitchew dove into Automatism— tapping the subconscious — as a significant tool in creating his metamorphic compositions.

Blodgett’s approach was more complicated than Tchelitchew’s and he typically left his sitters with their flesh only partially peeled away, revealing muscles, tendons, and bones. He wrote that he had set out to dive deeper in his quest for truth in art. This quest was reinforced by his immersion in art history, literature, and poetry as critical to his process of discovering his true artistic self. A clue is found in a college term paper from 1962 wherein he compared and contrasted the Pre-Raphaelites of Germany (the Nazarenes) with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of England. He empathized with the artists of both movements because “The Nazarenes were utterly other-worldly, speaking only with a religious tone, while the Pre-Raphaelites struggled with the very cause of their mental anguish…The vehement perseverance with which they worked was an extension of the force with which they felt their own conceptions.” Blodgett, too, had to deal with the mental anguish of his youth while recognizing that the source of that anguish was the catalyst that propelled his deep dives into spiritual realms.

Indeed, Blodgett’s anguishing rite of passage through detox is expressed in an extraordinary series of large drawing-paintings that depict him propped up in bed late at night, his room lit only by the glow of the television. Ghosts, demons, and sirens swirl around him, tempting him to drink from the bottle of whisky sitting on his night table. When Blodgett came up for air after his long and exhausting drawing sessions he relied upon a companion to care for him. He met his next significant muse, Amber, after a few years of being sober. She remained with him for five years, from 1989 to 1994. She explained that his work sessions were so intense that “If he was in a particularly bad mood, he couldn’t or wouldn’t eat. When he was ‘on a run’ working on a piece, he’d often go long periods without eating and then come crashing down afterwards and feel quite sick. That is when he really needed someone there to help take care of him.” Blodgett’s daily writings often refer to his “evening sickness,” which developed during twilight. Amber observed that the transition to evening often turned him into a different person, like Jekyll and Hyde. “Perhaps he was triggered by the shift in light and felt a kind of physical and emotional sickness, with the ghosts and demons coming into him.”

Having grown up in the Beat Generation and then maturing at the center of the hippie counterculture of the 1960s, Blodgett also experimented with “magic mushrooms” (psilocybin mushrooms), LSD, opium, hashish, and other drugs but he ultimately settled on marijuana. “Mushrooms make you feel shaky and things are brighter — I have a sense of well-being absolutely mixed with a sense of great loss.” After he beat alcohol he nonetheless continued to smoke marijuana daily as treatment for his glaucoma, and to induce a platform for creativity. “Smoking in the evening as much as I feel I need — and working it off is one of the finest of feelings,” he wrote. “There are major devils I have to conquer and I think I can learn how to do it without dope if I can learn enough on dope.”

In order to pay for necessities Blodgett asked friends and family for money, alternating between them so that his requests did not appear to be so frequent. He also relied heavily upon his female companions, whose steady jobs helped pay for everything from cat food to art supplies to pot. Occasionally he would trust someone enough to show them his work, and if he could tell that they were awestruck, he would agree to sell to them at what were high prices for the time. For example, the administrator at the ophthalmology clinic that treated him purchased several large works, paying over years in monthly installments. Even though Blodgett’s collectors were of modest income he expected that, once anointed, they should continue to buy forever. When they stopped he went into tirades and ended the relationships.

“He felt a kinship with van Gogh,” said Amber. “He had empathy for van Gogh, what his life was like and what he went through, his emotional hardships…He said that people think you must have a big ego to paint but he said it was the complete opposite of that. You have to crush your ego and be a humble and pure messenger.” Accordingly, Blodgett was never shy about his expectation that others should not only respect his noble quest but support him as well. “But he was not all fury and hellfire,” Amber said. “I thought he had a tender soul…Maybe his art was a kind of seeking redemption for the battle he had inside him. There was definitely a religious aspect to it. And there was definitely a battle between darkness and light, literally on the paper. It was both a battle and a dance.”

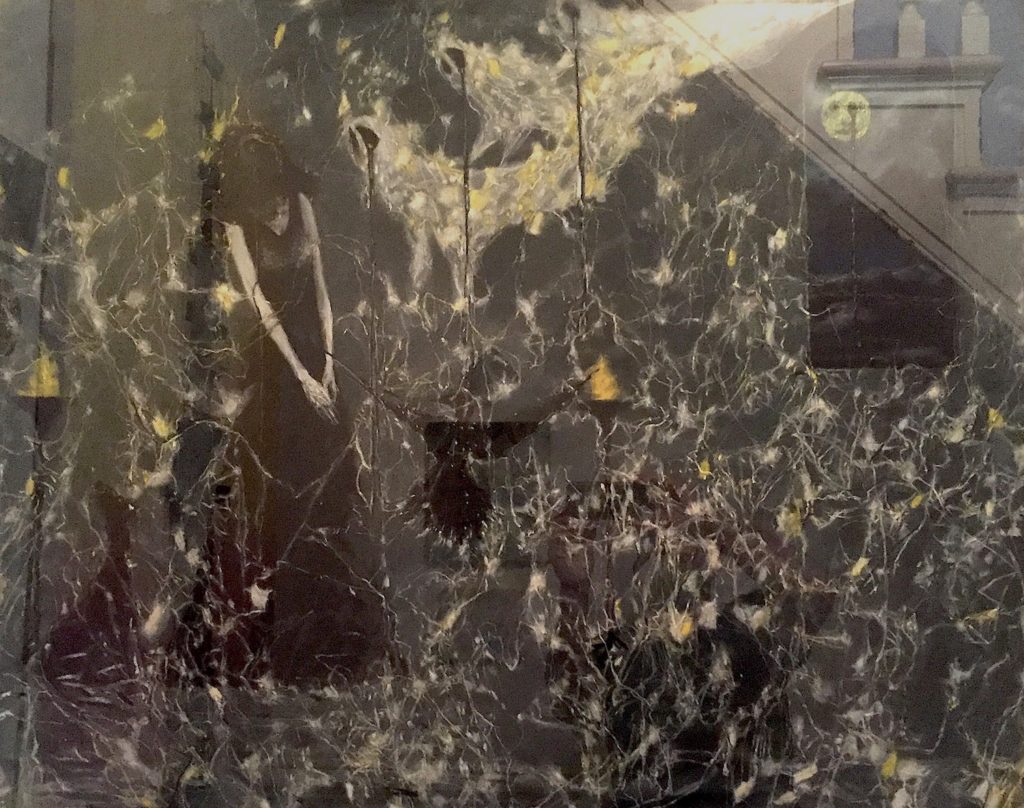

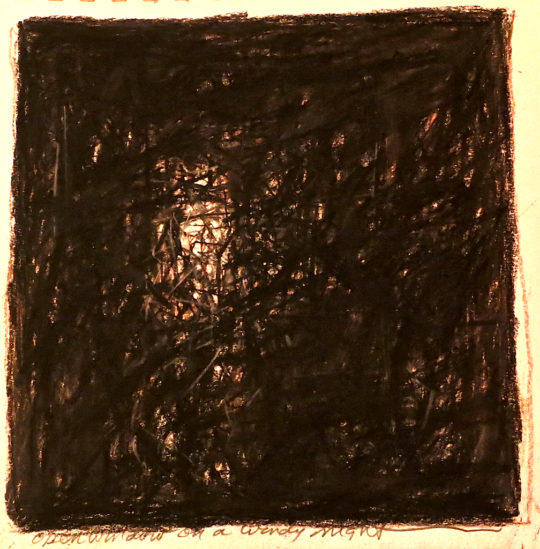

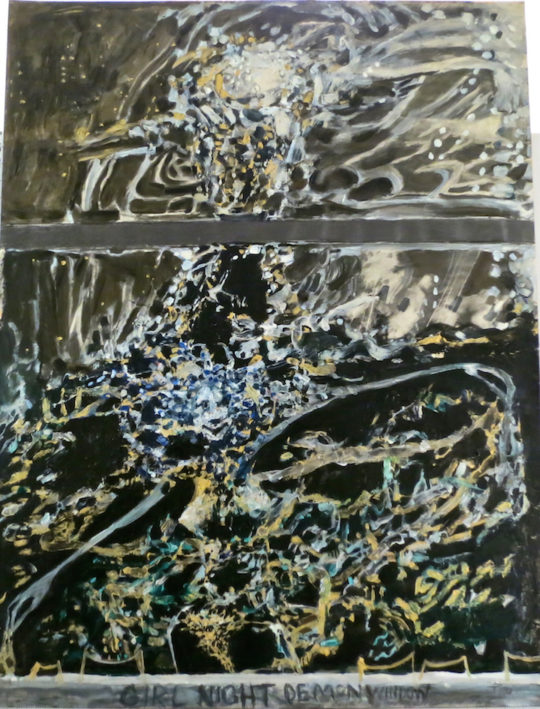

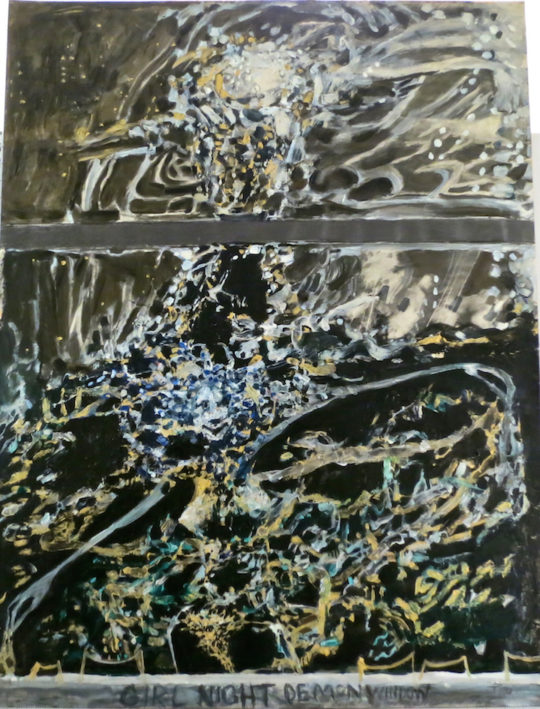

That battle and dance led to a unique expression in figurative drawing, portraiture, and landscapes. A series of nude drawings of Amber in the late 1980s again broke new ground in technique and concept as powerful expressions. And in 1990 he began the Window Series, an extraordinary group of works that document his forays into the unconscious. Working late into the night and gazing out his window into the bamboo jungle, he captured the female figure as temptress, often accompanied by ghosts and demons. The window frame itself divided the composition, and he brought the blackness of night alive with subtle lights, color, and depth. Sometimes he would later serve as narrator of his own drawing sessions. “We are shaky as shit but we are working right through the evening! And even with smoke that’s a victory for me. Never been able to do it this way without booze — and it was different — it was always a bridge. Now I can work.”

In addition to using the window, the mirror became another of Blodgett’s favorite entry points. He had discovered the use of the mirror while exploring the religious and spiritual concepts of non-literate cultures and studied the roots of “Voodoo.” He experimented with the centuries-old process of mirror gazing called scrying in order to conjure otherworldly beings to appear in a mirror. Blodgett was fascinated and intuitively understood the world of possibilities offered by the mirror. Here was another access point for deep diving into a new reality.

Supporting the Master

After Amber left in 1994 Blodgett experienced four difficult years struggling deeper into poverty. When he could not pay his taxes the city again gave notice that it would foreclose on his property. In the past he had from time to time taken part-time jobs as a laborer, including logging and railroad work. But manual labor was now impossible owing to a bad fall in 1984 (on an occasion when he was drunk) — and he had a long scar on his left shoulder as proof. If his financial situation weren’t dire enough he felt persecuted by Eugenians, and by extension, Oregonians, and he broadened his attack to include Americans in general. “One of the reasons I think that normal Americans are evil is because if I had to live inside their dark brains I’d find a way out. I’d bloody get out of that space or die trying. I mean, I did that anyway, didn’t I? But they don’t break out of their darkness. They don’t have the time for that. But mostly, they thrive inside that darkness. I don’t. I think I’m doing good work. If I’m right about that then evil has to be what’s going on to misunderstand me so completely.”

In 1996 Blodgett adopted a new signature that would forever serve to symbolize of his persecution — the unpronounceable symbol of a snake entwined around a cross. He also called his shack Crossnake Studios and called himself “Wolf Crossnake.” His new symbol conjoined the letter T (the cross) and the letter B (the rounded curves of the snake). He had in mind the Rod of Asclepius, the symbol of the ancient Greeks associated with healing. But the snake on the cross clearly carried a deeper personal symbolism — not only about how he felt as a crucified artist, but as one who had crossed the line as a deep diver into the abyss but kept managing to return (resurrection). Blodgett wrote, “I came up to the mark and crossed it” and made many references to “crossing the line.” In addition, Blodgett believed that because he was a creator he was close to God, so he saw himself as the snake wrapped on his cross — representing a Christ-like suffering and resurrection. He was inspired by the recording artist, Prince, known for his mononym, who had changed his stage name to a love symbol in 1993. When the state denied Blodgett’s application for the name change he became furious and felt even more persecuted. This came at a time when he was struggling to complete his largest masterpiece, an oil painting entitled The Death of an Idolater. “I’d love to get away from the painting,” he wrote. “It scares me. Maybe I can do it if I just go mad and stay that way for a month or so. It’s worth a try.” His ultimate goal — unfortunately unfulfilled — was to paint the entire interior of a cathedral.

Despite Blodgett’s need for help he had become particularly adept at driving people away as soon as he discovered that they lacked a sufficient level of imagination and intelligence. Nevertheless, as much as his reputation had spread for being an irascible character, he was also notoriously charismatic, attracting students to his private drawing workshops. Fortunately, some financial respite came in 1998 when several fiercely loyal students banded together to help him. They had been drawn as much for his hands-on teaching skills as well as his philosophy, and he recognized their potential. During the next five years the group would gather about him for drawing sessions, amazed at his ambidextrous skills. The sessions would also abound with his dictums. He exhorted his students, “Art only welcomes people who are willing to have their lives changed.” Every day he posted signs at the entrance for them, typically warnings such as “If you don’t expect me to be you, then I won’t make you look silly by expecting you to be me.” Always intimidating were his constant reminders that they faced a huge challenge to rise above their status as mere students. Typically, he would make decrees such as, “The difference between me and you makes all the difference in the world.” On the other hand, students who survived passage through the Blodgett gauntlet were lifted to the special status of apprentice and studio assistant. He cared deeply for them, and warned them of the dangers inherent for artists who must deal with the philistines that surrounded them. “Dialogue about art with an American is the same thing as debating anything with an American,” he wrote. “It’s like spitting in the desert and expecting roses to grow.”

One of Blodgett’s most ardent apprentices was Rich, who Blodgett renamed “Spider.” Rich recalled that his small group reached out to the arts and culture organizations of the city, state, and beyond in order to win recognition for Blodgett “but without any real connections to the art world and an abject lack of monetary resources, the most we could often do was keep him in paints while working in the best conditions we could provide.” Another key apprentice was Kris, who also became his third significant companion and model. She also stayed for five years and took on two jobs while assuming the role of caregiver. Noting Blodgett’s still finicky eating habits, she recalled, “He did not eat very much during the day — just a handful of dark chocolate and many cups of tea. He smoked a bunch of filter-less cigarettes and many hits of pot. The manic nature of his output had something to do with this routine of starving and keeping on edge.” She also observed that during his wakeful late night drawing sessions he demanded never to be disturbed as he made his forays into the unconscious. Blodgett made similar journeys even while he was finally asleep and dreaming, and Kris recalled a number of his sleepwalking nightmares. Once, he awakened her with a voice that was oddly grave and low. “He had black eyes, and was circling the house ranting. It was dark and frightening. It took him a few hours to come down. By the third one I was able to get in his face and yell ‘I am Kris; I am not the enemy!’”

Blodgett’s total immersion in his art was so complete that he felt justified in expecting his muses and students to provide him the financial support and caregiving he needed so that he could continue to pursue his noble quest. He viewed that quest as being rooted in the tandem of both art and science because “they are the paths to the door of the truth of the myth of the self — and prayer is the energy that keeps the truth true to itself.” Unfortunately, the master was by nature so intense and confrontational that he could also leave emotional scars on the very people who were dedicated to helping him. “I really have a bit of PTSD about my time at the studio,” commented Kris. “But as my creative life is solid now and has a platform and output, it is good to put to rest the fear that Tom is watching saying ‘dive deeper, you are not good enough.’”

Blodgett’s apprentices understood that he was not full of bravado when he proclaimed “I can outdraw anyone in this country.” But as the years passed the apprentices felt increasing pressure from relatives who were concerned that the devotion to Blodgett had gone too far — even fearing that he had used traumatic bonding to form a cult to further his own artistic quest. All of the apprentices reject that notion as illusory. “Yes, some people assumed that what went on in the shack was cult-like because it was well known that Tom required intense commitments in his relationships,” explained one of the apprentices, Greg — who Blodgett renamed “Archie Goodwin.” “And that meant an intense relationship with the work of art because he was accessing part of his being that few of us will ever reach and he was trying to share it with us.” Greg points out that Blodgett always maintained the relationship as that of master-to-student. “Tom held court. He loved to teach. He gave philosophy lessons every day and the themes always varied. He would expand our imagination so that we would go beyond what we would normally do. Ultimately, he was trying to save us.” Nevertheless, an apprentice’s life with Blodgett ran from exhilaration to dejection. By 2002 one-by-one they had left him. In his notebooks, Blodgett’s response to the loss would be to recall Barbara Streisand’s 1964 hit song, “People” — but Blodgett the contrarian would sarcastically write, “People who need people are the unluckiest people in the world.”

Fortunately for Blodgett, his needs continued to be fulfilled by the contiguous appearance of two more key apprentices. One was Kerry — nicknamed “Sam” — and he considered her the most empathic of all his companions. His new studio assistant, “Will,” noted that Blodgett continued his practice of working late into the night into the early morning hours. Sometimes he would push on for more than twenty-four hours straight, pausing only to drink lemon water or smoke a joint — and adamant about not being interrupted. Blodgett proclaimed that “Being interrupted is an act of violence” because he saw his paintings not as objects but as living spirits.

Blodgett thrived on teaching — and admonishing — his new apprentices. In 2004 he wrote,

“Since no one hereabouts knows the first thing about what ART is let me mention a few things that ART is not:

ART is not you.

ART is not a competition.

ART is not a talent show.

ART is not democratic, nor does it have anything to do with democracy.

ART is not a game.

ART is not for everyone.

ART is not unresolved.

ART is not self-expression.

ART is not you.

You are not ART.

ART is not trivial, mundane, or interesting.

ART is not about you as you ARE.

ART is about what you could become.”

Dénoument

In a virtually predictable cycle, Sam would depart in 2007. With the exception of regular visits from Will, and Victor the taxi driver — and the kindness of his neighbor, Anne, the master would spend his last five years virtually alone. The last of his seven adopted stray cats — an old scruffy wild Maine Coon cat named Hazel — remained to provide company and comfort in his loneliness. “I have to realize the transcendence of this kind of place, this kind of aloneness, this kind of being left more than alone,” he wrote. “I have to be alone and alone. I have to forget to remember. And I have to make everything that costs me real from today on — til it’s over. Big words. Laughable words to the people, I know it. But they are the little simple truth here and now.”

During the winters Blodgett typically sat shivering in his shack, writing about his artistic journey and wondering how he remained neglected and impoverished at the edge of what he called an artless city — a city that was once again closing in on claiming his property owing to unpaid taxes. Suddenly, he received news that his second and fourth wife, Linda, had died and left him eight hundred thousand dollars. (They had split up within a year of marrying in 1969 and in 1984 reunited in marriage. However, they soon split up again but never formally divorced.) With this extraordinary stroke of good luck he designed a new home and tore down the shack while living temporarily in a sleek Airstream trailer. In those tight quarters he turned to producing numerous small drawings of favorite subjects, including animals, ghosts, nudes, and Western landscapes. Reflecting on his benefactor, who he referred to as the “crazy one,” he wrote, “Linda never once believed in my work. Not once. Not for a second. Not believing in my work was a stop on her road to madness.”

Tragically, Blodgett would only enjoy the pleasure of working in his new studio for two years when in 2011 he received the dreaded diagnosis that the lump that had been growing on his neck was cancerous. Just a year earlier he had quickly adjusted to his new spacious studio, painting with vigor. “Thirty-three hours straight on the painting. Not bad for an old man of seventy.” Despite his loneliness, family members did reach out to him over the years only to be angrily rejected — as if his goal was to become completely estranged from them. He bitterly predicted that they would dismiss him as insane. Indeed, a niece recalled, “I always struggled with thinking he was either the genius he thought he was or completely insane. In the last few years, I surmised he had spent so much time in his mind, in his darkness, his demons and aloneness that he completely lost touch with reality and couldn’t find his way back. I then sadly felt for the first time that he truly was insane.”

But Blodgett was most certainly a gravely misunderstood artistic genius. Despite his cancer he continued to be prolific in his creations. “Before I die,” Blodgett declared, “I will create four magic paintings: Raunchy; Mystery Train; Heartbreak Hotel; and, Curtain of Tears.” Of course, he continued to create to the very end. “Oh, what a night. Oh-oh oh, what a night!” he exclaimed. “Finished two pieces — both with magic in them.” After a period of remission the cancer took a tenacious turn for the worse and worked its own nefarious magic. On October 2nd 2012, before 4:00 in the morning the weather in Eugene was calm. The wind was at a standstill. Suddenly, a strong gust of wind swept in from the northwest and Tom Blodgett was gone.

Blodgett also continued to write until the very end, and left behind many lines that could have served as epitaphs. As the philosopher he wrote, “What’s life about? It’s about you proving that you belonged here after all.” Blodgett’s works testify that he was a rara avis among artists of any time — even as one who chose to roost in a shack in the hills. At once he declared his mastery, his independence, and his fate: “A real artist is the first and last of his breed.” He was supremely confident of his gifts and knew he had dived deeper than most artists could ever imagine. He felt his paintings were brought back from the depths of reality and breathed powerful truths. “Art is not about how it looks,” he wrote, “but what it does.”

Ultimately, he wrote his own epitaph, underscoring his unique position in American art history: “Just Me.”

— Peter Hastings Falk

December 2014

Sources

Blodgett filled hundreds of notebooks and thousands of loose sheet of paper with his writings. Articles in regional periodicals provided additional information, such as Bob Keefer’s “An Artist’s Angst” [Eugene: Register-Guard, 14 March 1999, p.1B]

When Surreal is Real

-

DETAILS

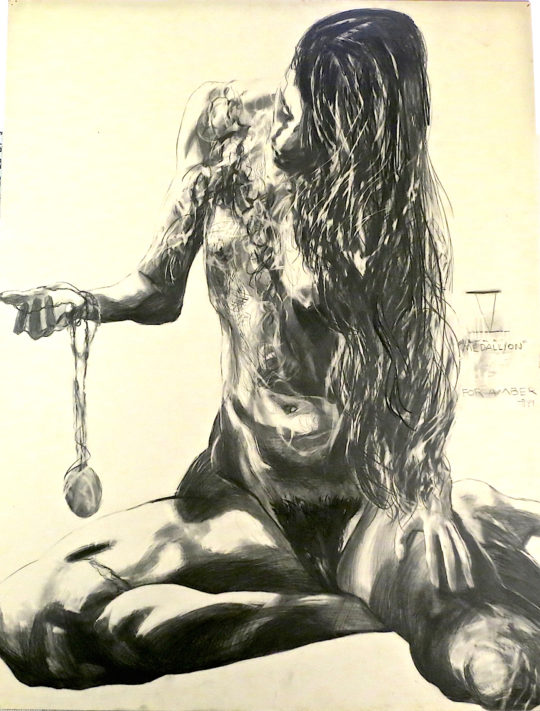

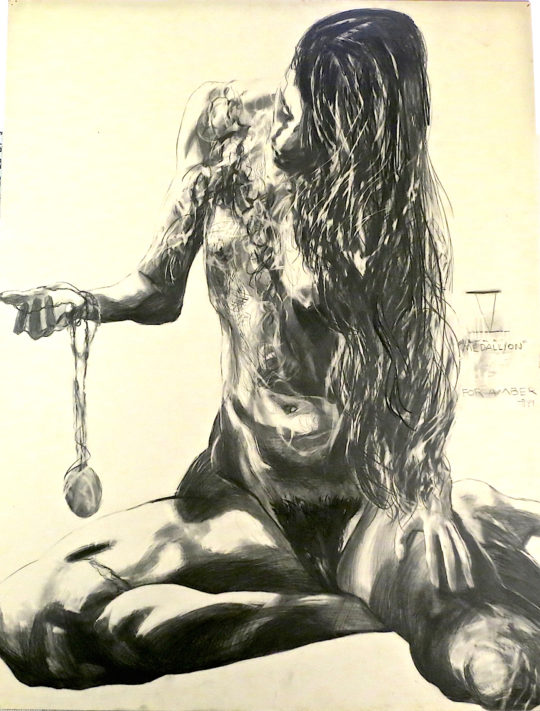

DETAILSAmber Series (V) Medallion, 1989

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBottomed Out series No.1: Reverence, 1987

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBottomed Out series, No.3: Dark Man’s Candy, 1987

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

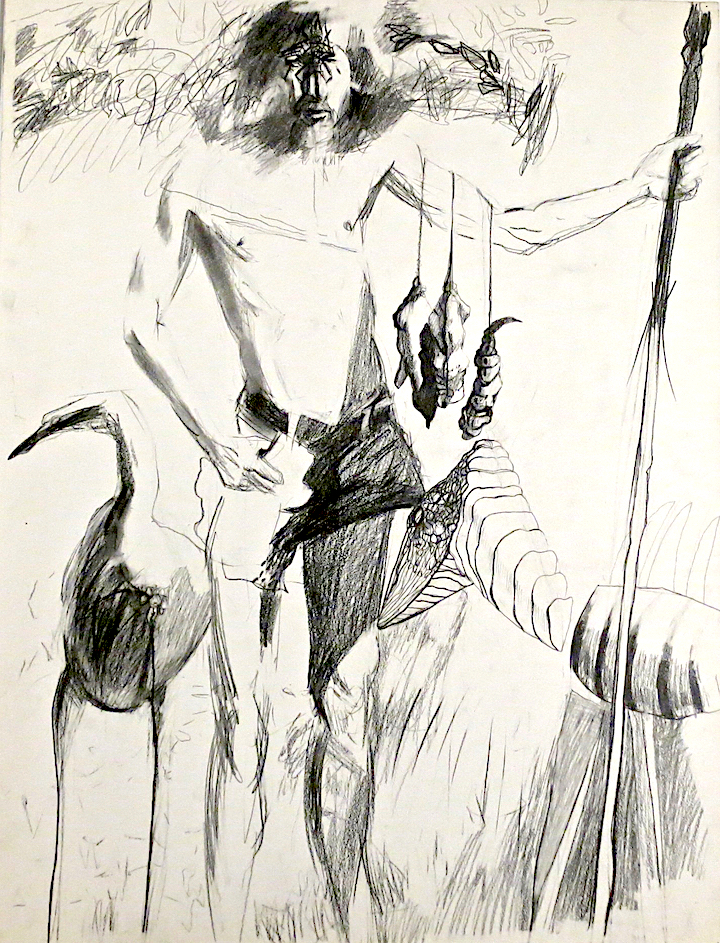

DETAILSEarly surrealism series: “Gifts”, 1972

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEarly surrealism series: “Hi Tom!”, 1972

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEarly surrealism series: Salmon, 1972

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

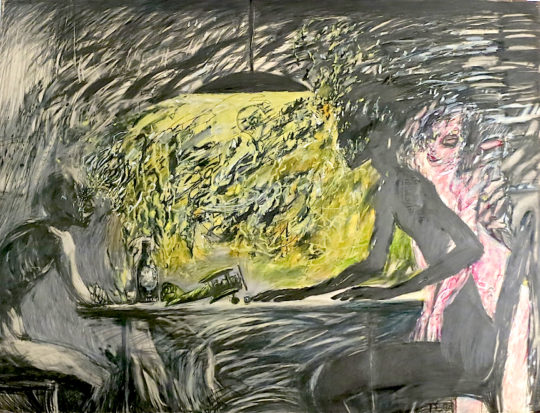

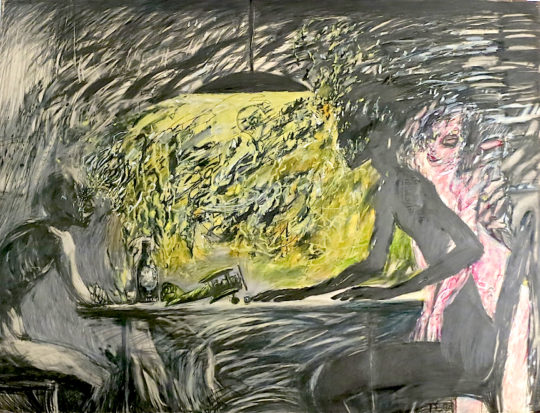

DETAILSFilm Noir series: I saw you yesterday in the woods, 1987

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

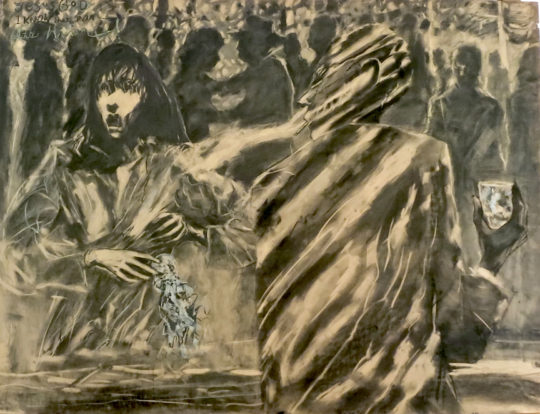

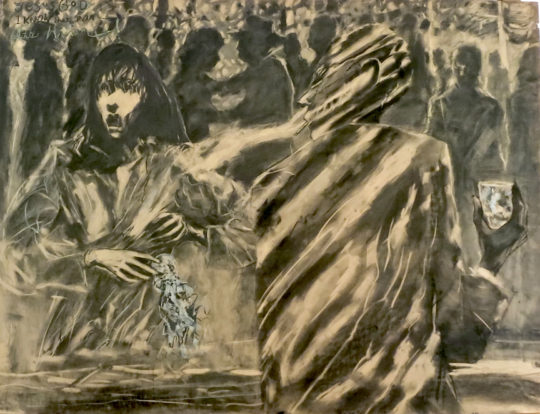

DETAILSFilm Noir series: Jesus God I know that man!, 1987

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFilm Noir Series: Love is a Dog From Hell, 1986

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFilm Noir series: Untitled, 1987

30 x 25 inches (76.2 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

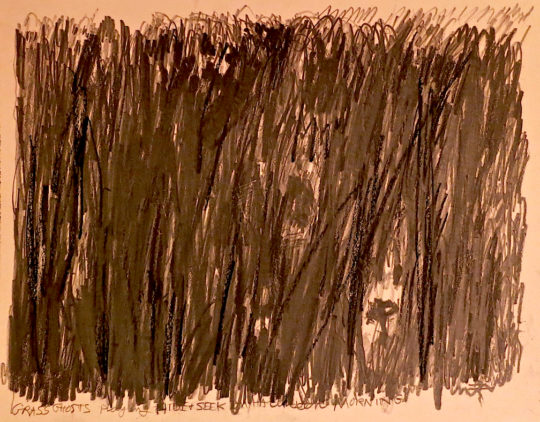

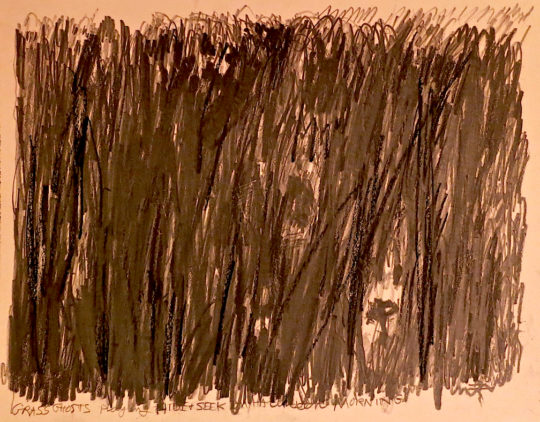

DETAILSGhostland Series: Grass Ghosts Play Hide and Seek on Halloween Morning, 2004

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

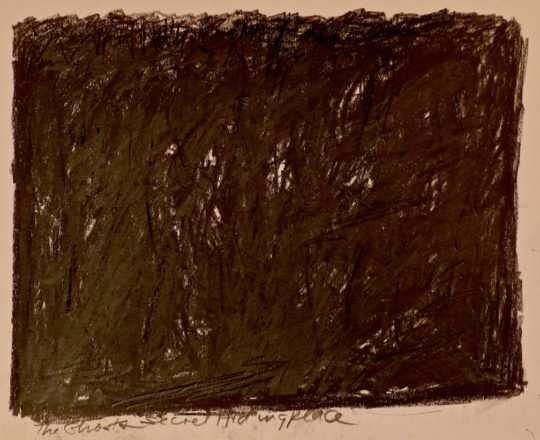

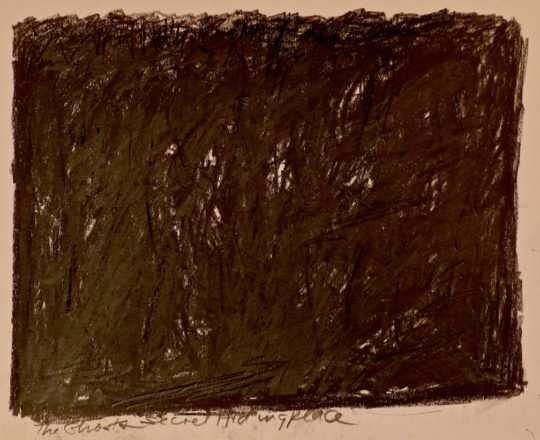

DETAILSGhostland Series: The Ghosts’ Secret Hiding Place, 2004

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

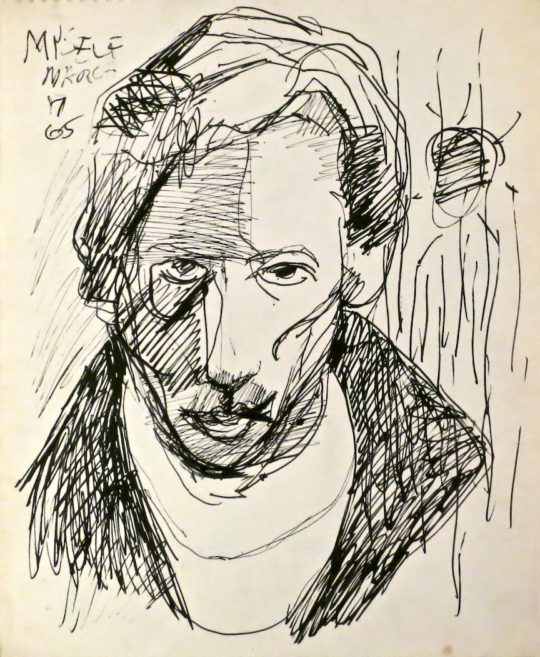

DETAILSMy Self, 1965

13.5 x 16.5 inches (34.29 x 41.91 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude and ghost, 1990

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

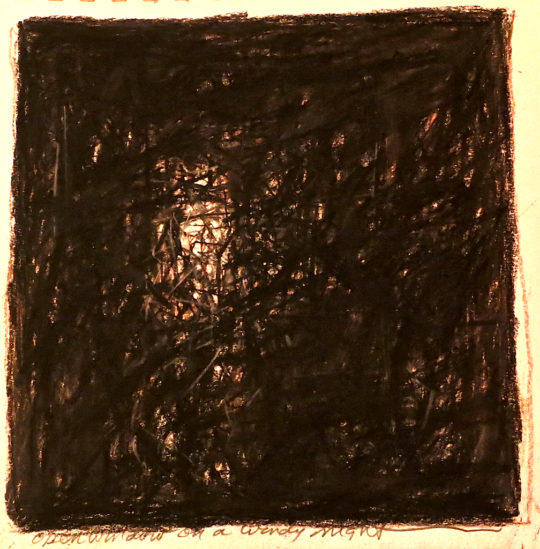

DETAILSOpen Window on a Windy Night, 2004

7 x 7 inches (17.78 x 17.78 cm) -

DETAILS

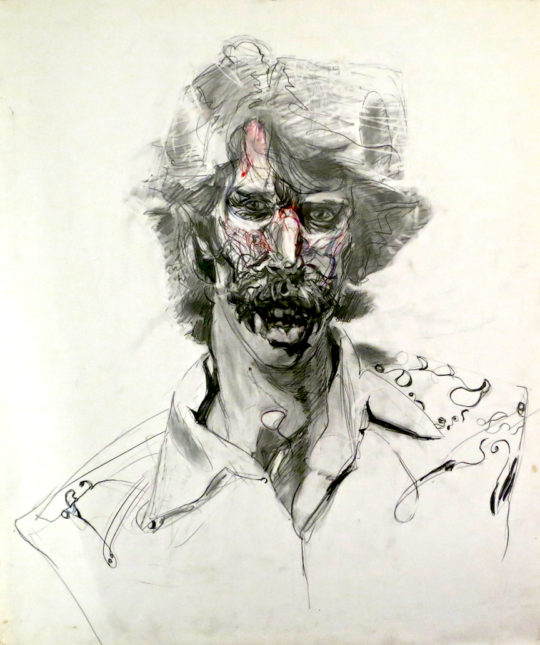

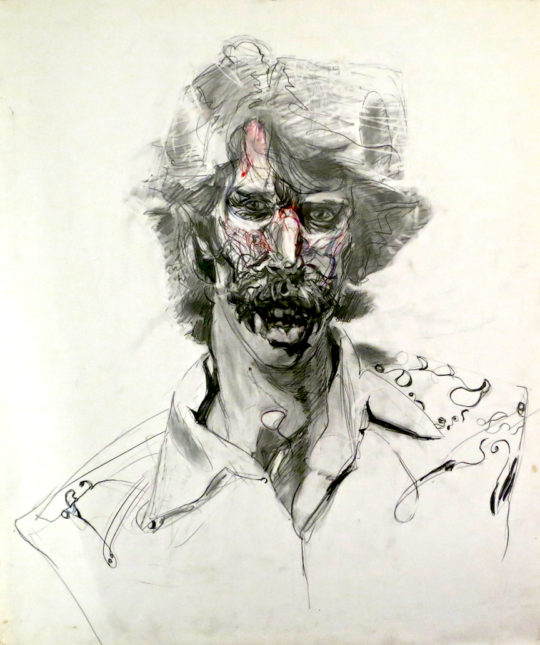

DETAILSPortrait series: a young man, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: age 29, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: age 33, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: David George Foster, Art Professor, 1979

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait Series: Malcolm Lowry, 1983

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: Self-portrait ten years later at age 48, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: Weltzen (Bill) Blix, Sculptor, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: Woman in Purple, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

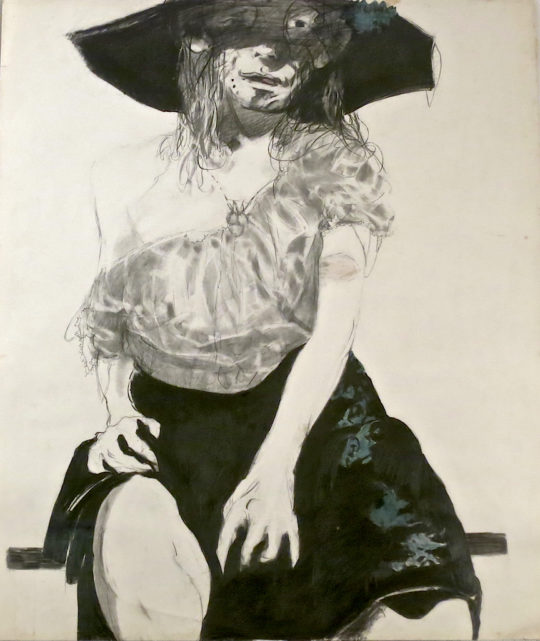

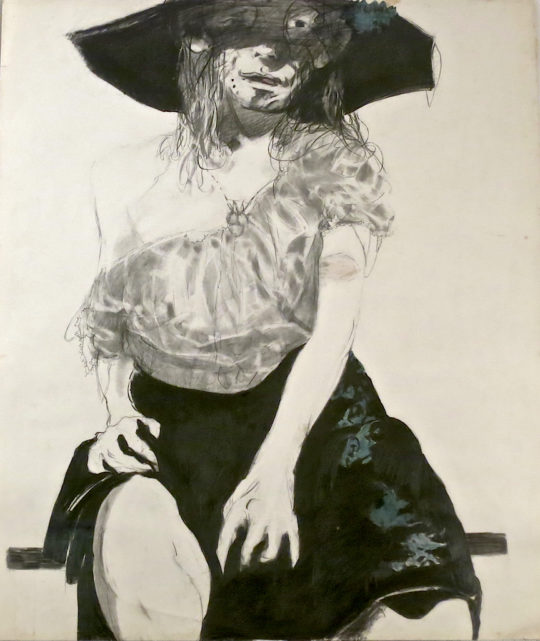

DETAILSPortrait series: woman with broad hat, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait Series: Woman with Sea Creatures, 1978

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

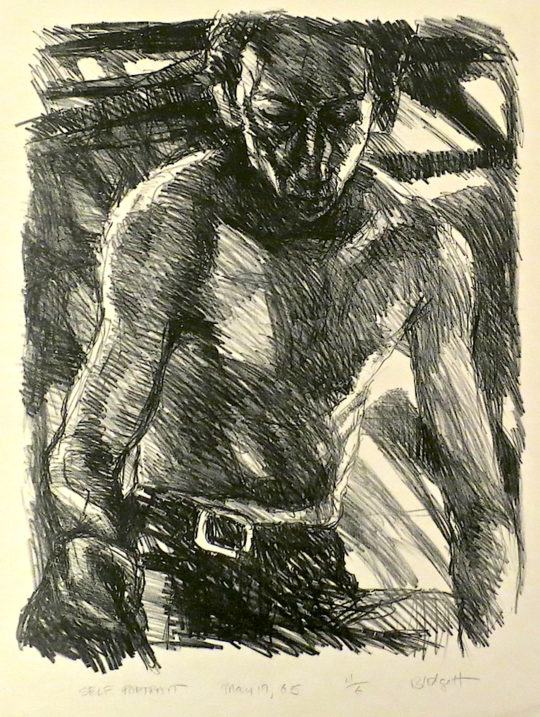

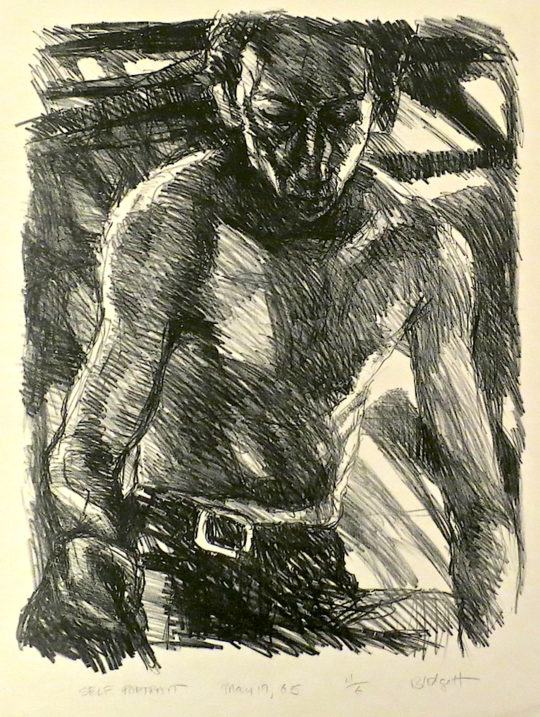

DETAILSSelf Portrait, 1965

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf Portrait, 1965

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwilight Birds, 1996

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2009

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2012

30 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

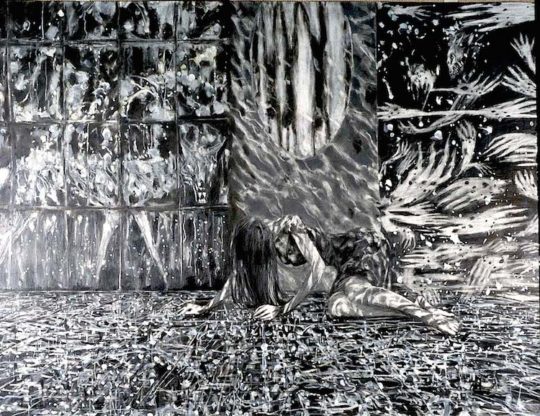

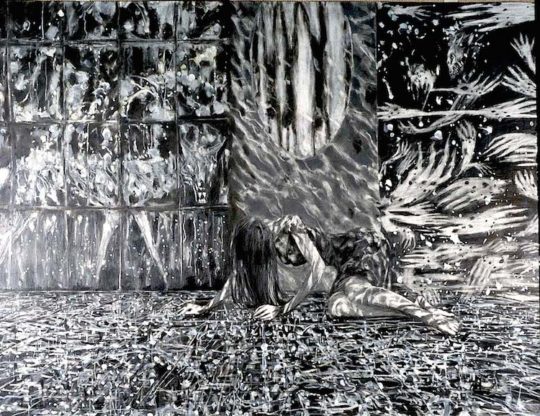

DETAILSWindow series: Bleak Spring, 1990

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWindow series: Girl Night Demon, 1990

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSAmber Series (V) Medallion, 1989

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBottomed Out series No.1: Reverence, 1987

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBottomed Out series, No.3: Dark Man’s Candy, 1987

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEarly surrealism series: “Gifts”, 1972

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEarly surrealism series: “Hi Tom!”, 1972

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEarly surrealism series: Salmon, 1972

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFilm Noir series: I saw you yesterday in the woods, 1987

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFilm Noir series: Jesus God I know that man!, 1987

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFilm Noir Series: Love is a Dog From Hell, 1986

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFilm Noir series: Untitled, 1987

30 x 25 inches (76.2 x 63.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGhostland Series: Grass Ghosts Play Hide and Seek on Halloween Morning, 2004

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGhostland Series: The Ghosts’ Secret Hiding Place, 2004

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

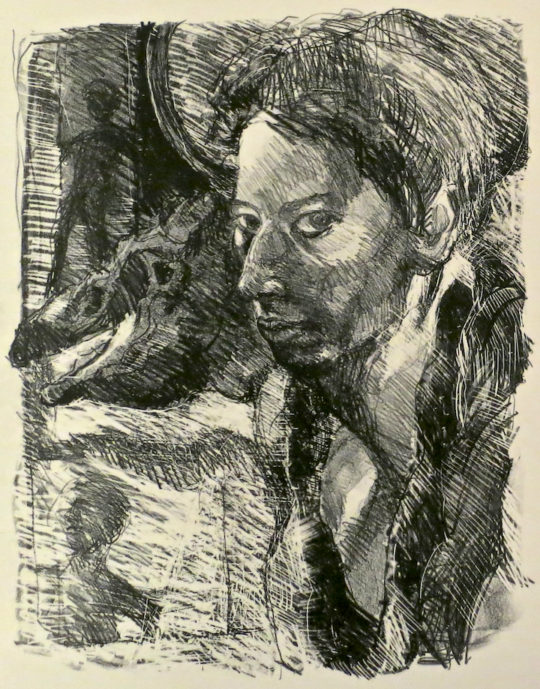

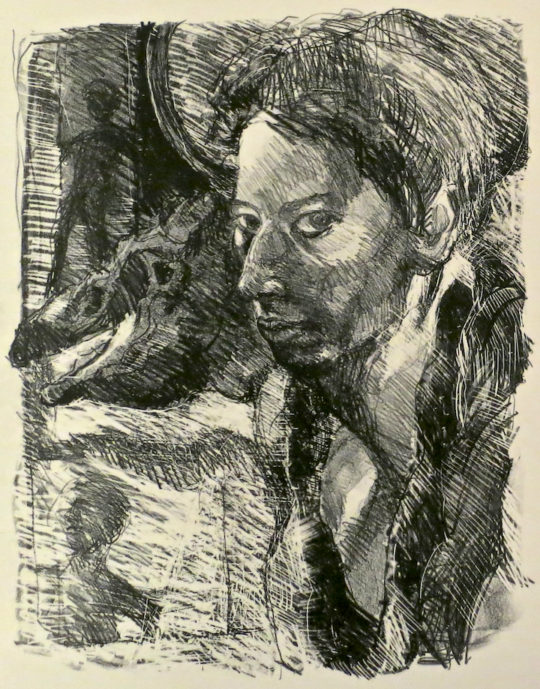

DETAILSMy Self, 1965

13.5 x 16.5 inches (34.29 x 41.91 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude and ghost, 1990

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOpen Window on a Windy Night, 2004

7 x 7 inches (17.78 x 17.78 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: a young man, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: age 29, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: age 33, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

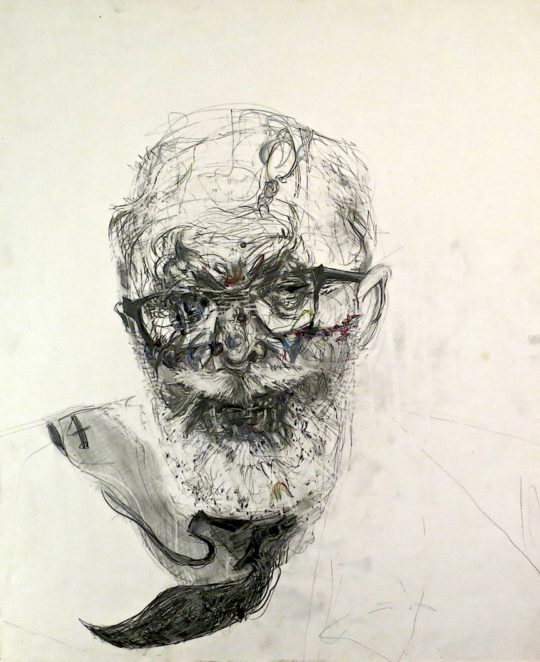

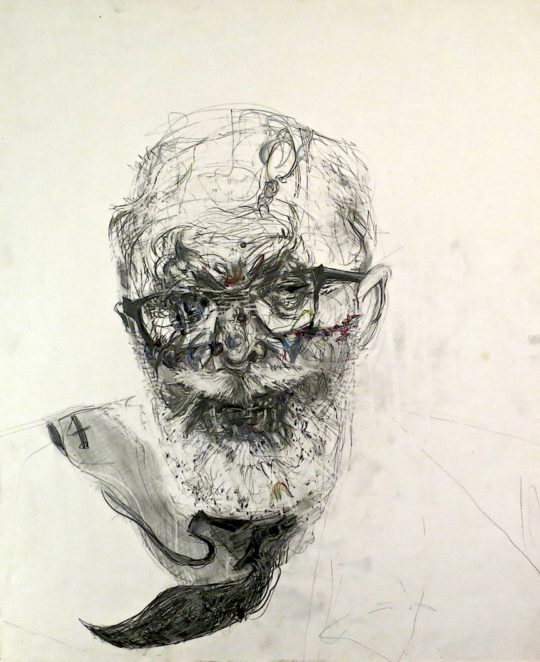

DETAILSPortrait series: David George Foster, Art Professor, 1979

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

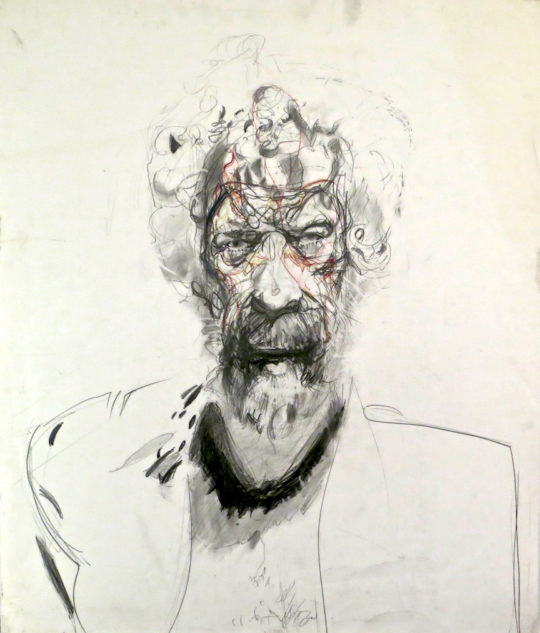

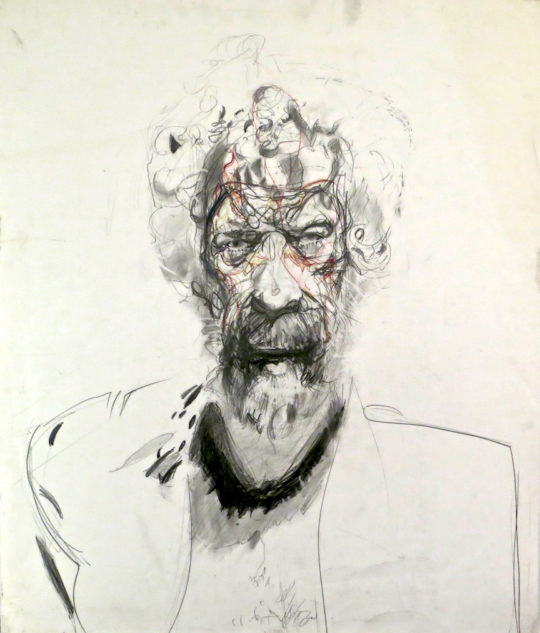

DETAILSPortrait Series: Malcolm Lowry, 1983

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

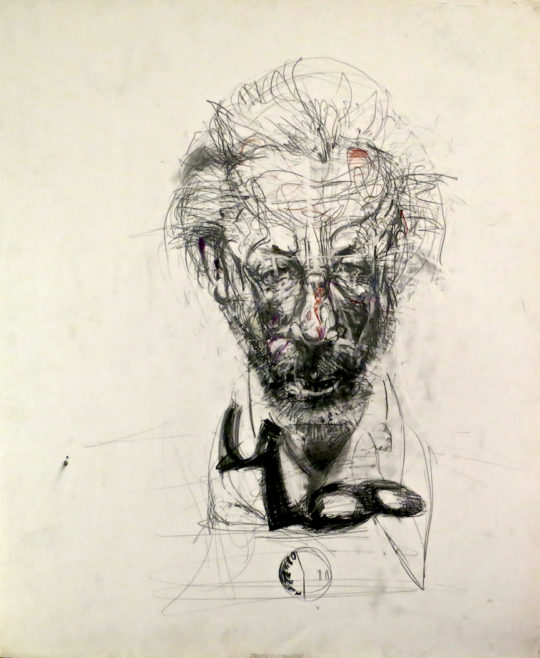

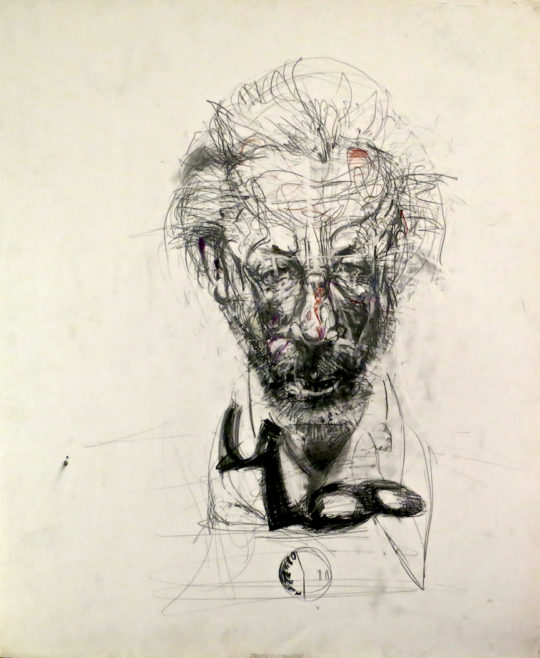

DETAILSPortrait series: Self-portrait ten years later at age 48, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: Weltzen (Bill) Blix, Sculptor, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: Woman in Purple, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait series: woman with broad hat, 1978

25 x 30 inches (63.5 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait Series: Woman with Sea Creatures, 1978

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf Portrait, 1965

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf Portrait, 1965

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwilight Birds, 1996

14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2009

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 2012

30 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWindow series: Bleak Spring, 1990

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWindow series: Girl Night Demon, 1990

30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

No Events Found.