For some significant artists, despite lifetimes focused upon expressing innovative and compelling visions, the sad truth is that their life’s work of may never come to be widely appreciated. Some even enjoyed fame for brief periods before becoming de-railed and ultimately marginalized or forgotten. Just a few of the common reasons include drugs and alcohol, psychoses, personality disorders, and agoraphobia. So undeniable is the quality and historical significance of their works that rectification — illuminating and reassessing these lives in art — is a moral imperative.

The case of Stewart Hitch reveals one collection to be a puzzle that may never be put together again. Even though his works are in twenty museums, including the National Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Broad Museum, his estate collection of 100 works has never been recovered, instead resting submerged in the depths of tragedy and controversy. In 1990, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith described Hitch as “one of the best underknown painters around.” In 2002 she wrote his obituary for the Times, explaining that just before Hitch died of liver cancer his last struggle was a futile attempt to recover his life’s work from a con man who placed it all in storage for safe-keeping. Smith alluded to the root of the problem being Hitch’s rough and tumble lifestyle — one that so idolized fellow Nebraskan Jackson Pollock that it was steeped in “painting energetically, womanizing rapaciously, and drinking ferociously.” His behavior notwithstanding, in his thirty years in New York Hitch developed “an engaging style that merged modernist geometric abstraction with the saturated stained colors of Color Field painting and infused the hybrid with a light streetwise insouciance. His natural touch and distinctive sense of color earned him a strong underground reputation.”1

Leslie Kaufman, another writer for New York Times, revealed the most thorough investigative reporting in “The Lost Legacy of Stewart Hitch.” She described Hitch as one who virtually lived at Fanelli’s Cafe on Prince Street. He “was known as ‘Lord of Fanelli's’ and could be found tossing back his morning eye-opener as early as 10 a.m.” If alcohol was Hitch’s dénouement, the ultimate tragedy has been that the mystery surrounding the whereabouts of his paintings has persisted.2

Born in Lincoln, Nebraska in 1940, Hitch moved to New York in 1968, shortly after receiving his MFA from the University of Nebraska. He arrived in SoHo with its many artists struggling as squatters in abandoned run-down buildings bounded by the area’s cobblestone streets. “In worshiping the avatar of abstract expressionism and the ultimate rule-breaker, Mr. Hitch was not alone,” wrote Kaufman. “Pollock was a romanticized celebrity of art students across the nation during the period that evolved into the tumultuous 1960s. When these art students graduated, they often descended on New York, seeking a foothold in the new bohemia then emerging in Lower Manhattan. Unable to afford even Greenwich Village with its crumbling brownstones and tenements, many ended up in the industrial wasteland south of Houston Street. Mr. Hitch was among them.” For many years Hitch was a squatter at 85 Mercer Street, and his primary source of income came from his carpentry skills, needed by artists and galleries renovating SoHo’s lofts. His notoriety caught the attention of the writers of the 1971 film “The Panic in Needle Park,” starring Al Pacino as a drug dealer and con man. In the opening scene Hitch’s character is a hard-drinking painter played by Raúl Juliá.

Hitch’s first break came in 1975 with a solo exhibition at the Robert Freidus Gallery. Stylistically, Hitch’s spirit was rooted in Abstract Expressionism and Color Field, two movements that had peaked fifteen years earlier but continued to exert their force in the broader visual vocabulary of painters. Pop Art and Op Art were also among the succession of new movements that had just faded away, but geometric abstraction and Minimalism were still evolving in a dialogue that now included graffiti’s leading artists, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. It was in this environment that Hitch emerged with his signature style, greatly influenced by Rock ‘n Roll music, Color Field, and graffiti — a multi-pointed star. A unique shape-as-subject, the strongest of these star paintings reveal dense layers of oil stick in bright primary colors bursting from their backgrounds.

In 1979 Barbara Rose included Hitch’s star paintings in her seminal exhibition “American Painting: The Eighties” at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery. Soon after the Museum of Modern Art included his work in its exhibition, “New Art II: Surfaces/Textures” (1981) he was given a solo at the Harm Bouckaert Gallery (1983). This was followed by a solo at the Jack Shainman Gallery (1987). During this period Hitch garnered prestigious grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Tiffany Foundation, and the Gottlieb Foundation (twice).

Tragically, alcohol steadily increased its grip and by the mid 1980s Hitch had been married and divorced three times to artist-wives. During the 1990s alcohol was in such command that it displaced the flow of accolades, serious critical recognition, and awards. A bright light shined posthumously, in 2015, when a sound measure of reappraisal came from the inclusion of his paintings in the traveling exhibition, “The Dorothy & Herbert Vogel Collection: 50 Works for 50 States.” Renowned as collectors of New York’s avant-garde, the Vogels had developed a close relationship with Hitch in the 1970s when they acquired more than a dozen works.

We delight in bringing to the forefront another truly innovative painter for whom serious critical recognition was won, lost, and finally recovered. We also join that group of historians and collectors who, hoping to add an even greater measure of appreciation, remain on the lookout for his stolen collection.

— Peter Hastings Falk, January 2017

-

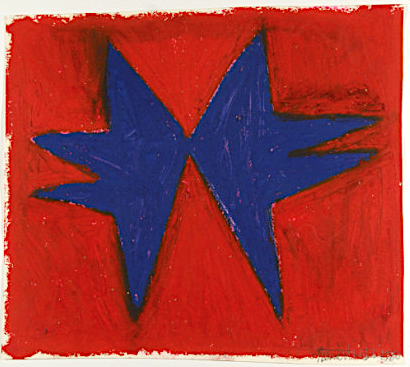

Road Rocket, 1980

9.37 x 10.75 inches (23.8 x 27.31 cm) -

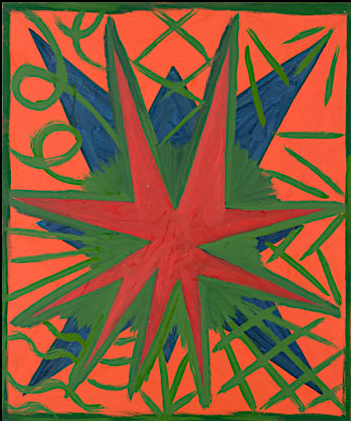

Schenevus, 1982

36 x 30 inches (91.44 x 76.2 cm) -

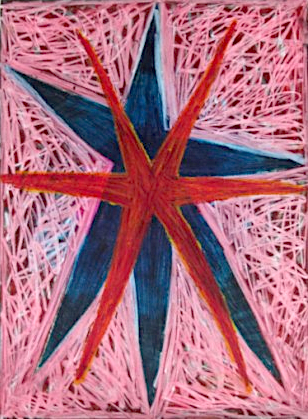

Straight Rider, 1980

40 x 40 inches (101.6 x 101.6 cm) -

Untitled, 1978

40 x 33 inches (101.6 x 83.82 cm) -

Untitled, 1984

22.5 x 15 inches (57.15 x 38.1 cm) -

Untitled, 1981

30 x 22.5 inches (76.2 x 57.15 cm) -

Untitled, 1981

30 x 22.12 inches (76.2 x 56.18 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

Midwestern Bulldog Abstractionist

When Stewart Hitch breezed into New York City on his motorcycle, he had high hopes of making it as an artist. Fresh from Lincoln, Nebraska, Stewart arrived in Lower Manhattan in 1968. He landed in what was then the largest community of artists the world had ever seen. Bigger than Athens under Pericles and international in the diversity of its inhabitants: this was SoHo; a neighborhood bound by Houston Street to the North and Canal Street at the Southern border, and consisting of unoccupied, abandoned manufacturing buildings with no plumbing or heating. Hitch was one of thousands who claimed these huge spaces for art studios. His first loft was on Greene Street, and it was used as a location in the movie “The Panic in Needle Park” with the, then young, Al Pacino.

But Hitch looked a lot more like James Dean. He stood about 5’ 7” with dirty blond hair, low gravelly voice, killer smile, and was made of pure muscle.

His tremendous upper body strength came from years of performing the Iron Cross on steady rings, which is still considered an impressive move in artistic and competitive gymnastics. It requires a certain build of muscles (wrist and arms) and technique. Hitch was strong and smart, and you could see both traits in his hands; hands that could have been a surgeon’s, built a log cabin from scratch, or, as he actually did, take apart his motorcycle and put it back together again so he could park it in his loft.

He was charismatic and a legend even before he came to New York City. His house, in Lincoln, was the go-to meeting place for artists; a rock ‘n’ roll, pot-smoking, beer-drinking, Midwestern version of Warhol’s Factory. When poet Allen Ginsberg came to talk at the University of Nebraska, he left his hotel to stay with Hitch.

This charisma lasted a lifetime, as did the incredible strength of body and character. It lasted through decades of groundbreaking paintings, fame and loss of fame, money and no money, wife and no wife. Hitch’s indomitable courage even carried him through an evening in a famed NYC artist bar when a crazy customer slit his throat with a piece of glass. Fortunately, the cut wasn’t deep enough to kill him or to sever his vocal cords. But alcohol was what got him in the end. The hard working, hard living, hard drinking cowboy painter was sideswiped.

The beginning of the end started in the 90s. After living in SoHo for over 30 years, Hitch lost his loft on Mercer Street and was kindly offered an apartment, in NYC’s Inwood area, by video artist Nam June Paik. Not too long after, doctors told him he had to stop drinking immediately or “you might as well jump off the Brooklyn Bridge.” Overnight and with no help, Hitch kicked the habit and gave up his daily occupancy at Fanelli’s bar on Prince Street. That Midwestern bulldog character was still intact.

He was broke but managed to make a new body of work that was part painting, but mostly assemblage. He stuck anything that came to mind onto his panels — including broken doll parts, pieces of furniture, newspaper, crumbling angels and saints, and glitter (glitter had always fascinated him, even in his early work). And, of all things, he became a regular on the TV show “Law and Order” taking on background work. He got an acting agent. He had hopes again.

But he was far from well; his liver had suffered too much damage. Stewart Hitch died in a hospital room uptown, far from his artist friends and even further from the cornfields of his youth whose color, shade, and rooted certitude informed his art. In his last moments, he called out for one of his oldest and truest friends, my husband, Thornton Willis. Willis ran to the hospital, but he arrived just a minute too late. Hitch was gone. Hitch’s mother and sister came to New York to claim his body. Pioneer-bred women, they made no recriminations or claims. Stoically, they took him home to Nebraska to rest among his kin.

——

The artists I came up with in the 70s were mostly men (including Stewart Hitch, Thornton Willis, Neil Jenney, Tom Evans, Dan Christensen, Kenny Showell, Richard Serra, James Little, and David Cummings) and none were city slickers. They were the sons of small business owners or farmers–pioneer stock–who valued honesty above all other virtues because their lives depended on it.

I thought then that people tied to the land like these artists have no reason to make abstract paintings unless they are real to them (the paintings I mean). Meeting these people confirmed for me that abstraction is real and truly American. Based on our principles of liberty and freedom, we gave birth to this way of making a statement visually, and it’s as American in origin as Jazz music.

——

Note from the author: Much of Stewart Hitch’s legacy has been lost. During the decades of mind-numbing drinking, he entrusted nearly all of his work (minus what had been sold) to another alcoholic who ended up stealing and possibly destroying it all, including a large sum of money that Hitch paid him to store his work in the first place.

Several of us who knew and loved Hitch got together after his death and hired a private detective to run down the guy and find the large stash of paintings and drawings. The writer Leslie Kaufman, wrote “The Lost Legacy Of Stewart Hitch” for the New York Times, Sunday edition, February 2, 2003 (The City Section, p. 12), which explains the situation in greater detail.

Despite our efforts, the work was never recovered and what remains is only a glimpse at Hitch’s incomparable facility and ability in handling paint and other mediums of expression. We hold onto these hints and signposts to remind ourselves of his greater artistic vision. Stewart Hitch was an extremely talented and prolific painter who intuited ahead of his time the need to combine the tenets of Abstract Expressionism with what is most authentic and American of Pop Art.

© 2019 Vered Lieb