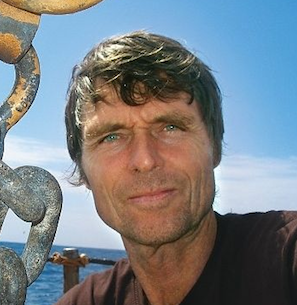

Reid Stowe, Psychonaut on the High Seas

“Tibetan lamas could be called psychonauts, since they journey across the frontiers of death into the in-between realm.”

— Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman

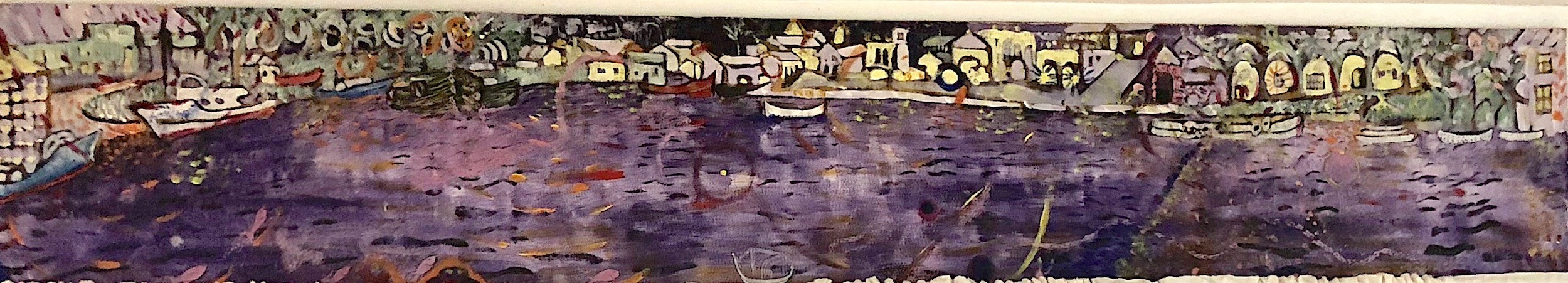

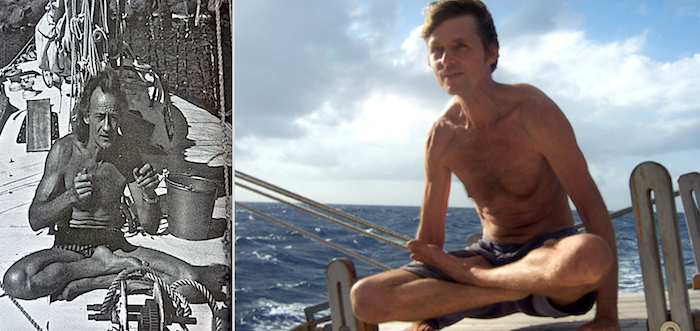

Reid Stowe has literally voyaged “across the frontiers of death into the in-between realm” since he was a teenager. It was not until 2018 that he decided to fully reveal that he has always led a double life. That parallel life has meant constantly creating art and sailing the world’s oceans. The result of this unique dynamic is a vision that is far apart from that of any other painter. When his last epic voyage ended in 2010 he had set a new oceanic endurance record of 1,152 days as the first person to sail for the longest period around the earth, in solitary, without touching shore, without resupply of food or water, and without fuel. It was so jaw-dropping that even the elite community of experienced ocean sailors was left incredulous that he survived. It even found Stowe ensconced in Ripley’s Believe it or Not. At the same time an artistic zenith was also achieved. Stowe’s large series of paintings defies being pigeon-holed with a particular style or tied to a specific movement.

The first reaction to these paintings is that they exude an integrity and authenticity. Then we discover they are the cumulative effect of spiritual experiences — from harrowing to sublime — upon the oceans. At the core of our understanding we come to discover an artist intuitively embracing an inner dialogue between his unconscious-spiritual-psychological life inseparable from his life on the oceans. For decades, Donald Kuspit, dean of American art historians and author of many notable books on modern and post-modern art (including his influential The End of Art) has challenged the validity of certain popular artists whose marketplace-crafted personas camouflage the truth of their roles as faux-revolutionary descendants of a tired Pop Art movement, effortlessly regurgitating a narcissistic conceptualism. He has been as surprised as anyone by Stowe’s paintings:

“Stowe is a serious discovery. He is a natural-born mystic whose long voyage seems to have been an extended religious transcendental experience — and what came out of it were paintings that are quite intriguing. They are not classifiable in any certain way. They seem to live in a borderline, exploring between the psychotic and the transcendental, spiritual experience. These works definitely come out of what the psychoanalyst Romain Rolland referred to in 1927 as, coincidentally, the ‘Oceanic Feeling.’ They are densely layered and as a body overlap with so many modern concepts in painting.”2

Sometimes Stowe’s imagery reveals itself as a subtle lure and at others as an explosion of visual effects; in both cases it is an invitation to view fragments from an unconscious realm into which few artists have ventured. Sometimes it takes a fiercely independent outsider and introspective artist like Stowe to remind us how the unconscious serves not only as a powerful source of inspiration but the only source that results in truly compelling art. Throughout history, those artists who have become recognized as “masters” have achieved such exalted status owing to their extraordinary abilities in expressing truly unique visions. For centuries, those visions have been realized through styles and techniques that are so innovative that they evoke from viewers an emotional reaction quite unlike any other. One hundred years ago, Clive Bell, the British art critic and champion of abstract art, put a name to its cause as “significant form” and to our response as “aesthetic ecstasy.”3 Without even knowing Stowe’s extraordinary back-story, his paintings can elicit this emotional reaction. Knowing his back-story reinforces the impact of the “ah-ha” moment.

Bell’s observations about our psychological and spiritual reactions to art gained renewed resonance in art criticism during the height of Abstract Expressionism in New York. Yet, art historians continue to struggle with a paradox inherent in contemporary art criticism. Some champion conceptualism — the opposite of Bell’s perception — sometimes encouraging a jaunty art market too often driven by commercialism. At that glittery end of the spectrum one finds artists anointed as “masters” by the marketplace despite their unawareness of (or delight in) producing works that are slavishly derivative, frolicking in the purely decorative, or confessing to a vapid imagination. Other critics deride the permission freely granted by Marcel Duchamp — that seminal conceptualist master of the early 20th century — to pursue what are seen as comfortably nihilistic subversions of “art” where both the unconscious and art history are denied. By the 1980s art historians had reawakened a vigor in the dialogue about the difference between a very conscious construction of art — as taught, for example, at the Bauhaus and by Josef Albers, later flowering in Geometric Abstraction and Minimalism — versus the unconscious expression inherent to movements such as Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. In 1987, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art mounted an influential exhibition (with an eponymous book) called The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985. That exhibition, whose title was drawn from Kandinsky’s seminal treatise of 1912, re-examined the history of abstract painting, revealing that the unconscious has always been a vital source of inspiration shared by masters.

Most recently, the artist-critic Ann McCoy wrote, “Artists who do draw from the unconscious are dismissed as throwbacks to an outdated Romanticism. Dreams, synchronicity, and visions are thought of as byproducts of bourgeois society and the irrational is to be avoided. Critical theory stresses art that is motivated by politics and society rather than subjectivity. Artists drawing from mythology, antiquity, alchemy, etc. are dismissed under the heading of ‘historicism.’ This abandonment of the unconscious seems to be more prevalent in the visual arts than in poetry, film, and theater.”4

The Psychonaut

In 1970 a new term — psychonaut — was coined for those who explored the unconscious and its altered states. The word means “a sailor of the soul” and aptly describes Stowe. Viewers standing before his large paintings — some actually 16-foot sails — realize they are oceans apart from marine panting. They experience brilliant Day-Glo colors as movements breaking free from geometric structural grids. They sometimes become so absorbed by their hallucinatory effects that they wonder if mind-altering drugs induced their creation. For Kandinsky color was psychic vibration. For Stowe color is more than a control over chromatic exuberance. He agrees with Mark Rothko’s statement that if a viewer was moved only by the color relationships in his paintings, then they missed the point.

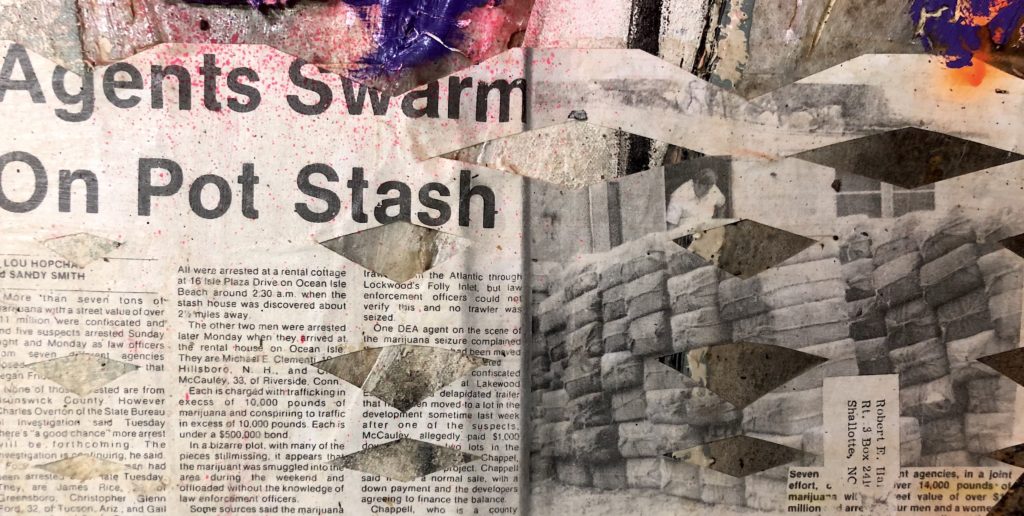

Stowe the psychonaut is not a follower of his controversial contemporary Timothy Leary (psychologist and author of The Psychedelic Experience), who urged Stowe’s generation to use LSD to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” Stowe the oceanic shaman has used psychoactive plants and other entheogenic substances but only to gain deeper insights and spiritual experiences, which were later translated into paintings. “The healing power of altered states of consciousness is no longer relegated to the counterculture of Timothy Leary” writes Michael Pollan, author of the recent book, How to Change Your Mind. “It’s entering the mainstream. There are now FDA-approved psychedelic therapists.”5 And while Stowe hopes that with pot’s legalization and its farming having become a multi-billion-dollar enterprise it may also be more acceptable to reveal that he was also one of the largest pot smugglers in American history. But that story comes later, as it pales before the significance of his artistic accomplishments.

The chapter that is truly extraordinary is one that enriches the history of abstract painting. It’s a chapter where phenomenal endurance is inextricably intertwined with artistic innovation. Stowe’s artistic path — from origin to evolution to maturity — is genuinely unique. Like other masters, he may be cast as the prototypical hero passionately pursuing a noble quest. Tracing these artists’ paths to fulfillment, we discover their persistence, their quirks, and their obsessions. We learn that their own personal voyages were often fraught with great difficulty and even tragedy (in America alone, think Gorky, Pollock, Rothko, Haring, and Stowe’s friend, Jean-Michel Basquiat). Quite unlike other masters, Stowe may be called art history’s first adventure hero — a hero who discovered a mystical source, and still taps it. If his paintings were not as compelling as his backstory he would have been politely dismissed. Instead, he would had to have settled for being ensconced in just one pantheon, that reserved for heroes of mythic endurance and courage, along with other fearless ocean explorers — but they always sailed with large crews. In the early 15th century Zeng He commanded an impressive Chinese royal fleet, becoming the first to circumnavigate the globe. In the mid 18th century Captain James Cook charted the Pacific Ocean. In the mid 19th century Charles Darwin sailed around the world proving his theories on evolution. Now, consider sailing solo around the world. In the late 19th century Joshua Slocum was the first to single-handedly circumnavigate the globe, albeit making landfalls. In 1967, Sir Francis Chichester made a solo circumnavigation of the world (with just one stop, in Australia) in 226 days. Two years later, Bernard Motissier sailed in the first non-stop, singlehanded Golden Globe Race sponsored by the Sunday Times in London, and was on target to win but for philosophical reasons instead decided to continue sailing back to Tahiti. In 1986, the greatest Australian sailor, Jon Sanders, logged 658 days. Finally, in 2010, Stowe broke all records with his 1,152 days at sea — more than three years. His extraordinary accomplishment became known as “1,000 Days — The Longest Sea Voyage in History.” When he finally docked in Manhattan neither the press nor anyone in the crowd on shore knew that more than one hundred paintings on tattered sails were stowed below decks. Few even knew that with the help of his father and brothers he had built his 70-foot, 60-ton Schooner Anne. Fewer still ever saw her bulkheads, into which Stowe had installed tropical woods he had hand-carved in haute-relief. Also aboard were carved wooden statues. It was an environment in which Gauguin would have delighted.

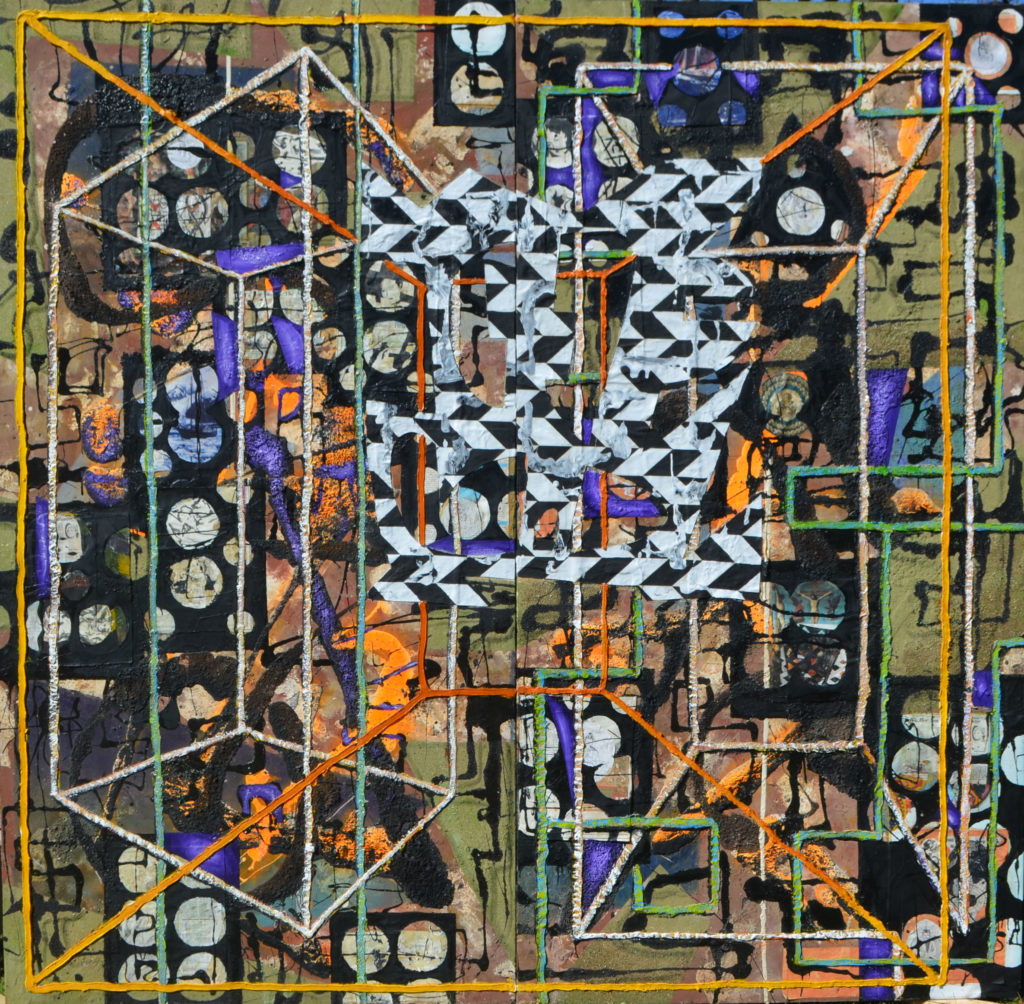

How then, does one come to understand Stowe’s art? Art historians are charged with the responsibility of immediately detecting whether an artist’s works are fearlessly innovative or slavishly derivative. Truly unique works are challenging, triggering an instinct to examine a broader spectrum of a life’s works with the hope of unraveling the mystery behind their creativity. Standing before Reid Stowe’s large paintings it becomes clear that he has broken from the mainstream art world. He is neither an insider nor an outsider. If anything he is inside-out, having absorbed and transmuted elements from nearly every movement from the 1950s to today, including Abstract Expressionism, Collage, Assemblage, Pop, Art Brut, Hard Edge, Op Art, Shaped Canvas, Abstract Illusionism, Arte Povera, Dada, Narrative, Outsider, Surrealism, Graffiti, Neo-Expressionism, Performance Art, and Neo-Geo. As a result, one encounters a dense layering of styles and imagery including graffiti figures, painted words, flat circles of color, mandalas, linear geometries, strips casting shadows, careful pouring and dripping, and carefully placed jolts of Day-Glo.6 Equally disarming is his use multiple techniques and mediums often combining house paint, spraypaint, acrylics, gold leaf, fragments of photographs, pieces of worn sails from his voyages, beach sand, sawdust, driftwood, sailing rope, and sail repair twine. Most of the pictures he cut from magazines and inserted as collage elements were storage diagrams, work lists, press coverage, and promotional materials — all related to his voyages were play a role of enlightening viewers but were more important because they empowered his vision. He often painted black & white checkerboard strips that appear to play the role of safety tape marking of a hazardous area. The final works sometimes break out of the expected rectangular canvas on stretcher bars and are instead irregular in shape because the chosen support material is an assemblage of large pieces of found driftwood. The result is a complex imagery drawing us in while begging to be decoded. A compelling multimedia painting by Stowe is the result of more than just this hybrid vigor. Digging deeper throughout six decades of paintings, one seeks answers to the evolution and maturity of his path. After long contemplative viewings, we art historians would never have imagined naming other-worldly oceanic experiences as the wellspring of this creativity.

Youth

In order to unravel the mystery behind Stowe’s works and why they represent a significant departure from mainstream contemporary art, one must first examine the dynamics of an unconscious source traced back to his childhood. By so doing we understand how he became the only painter in history whose artistic life force originated in and on the oceans in command of his own self-constructed sailboats on profoundly dangerous voyages. We also come to grasp why his spiritual and artistic evolution is so distinctive. “There is a big difference between being a guest on the sea and the captain of your own boat, having to make your own decisions to survive,” he says. “I took all that I had learned and experienced on the oceans and went into the psycho-spiritual realm to succeed in this voyage.” This is a crucial distinction that puts a light year between Stowe and any other artist.

At eighteen he painted Flying Above the Birds and Swimming Below the Porpoises Simultaneously. “Though I had started to break up the point of view as early as 13 years old, those paintings were more influenced by Picasso and Klee. This painting is the first showing the maturing of my mystical visions. Next, I painted a mural of that painting 10 feet square on the wall of my family’s beach house and it is still there. The success of this image allowed me to clearly hold those visions in my head for a lifetime.”

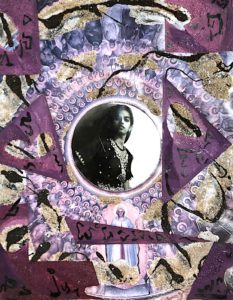

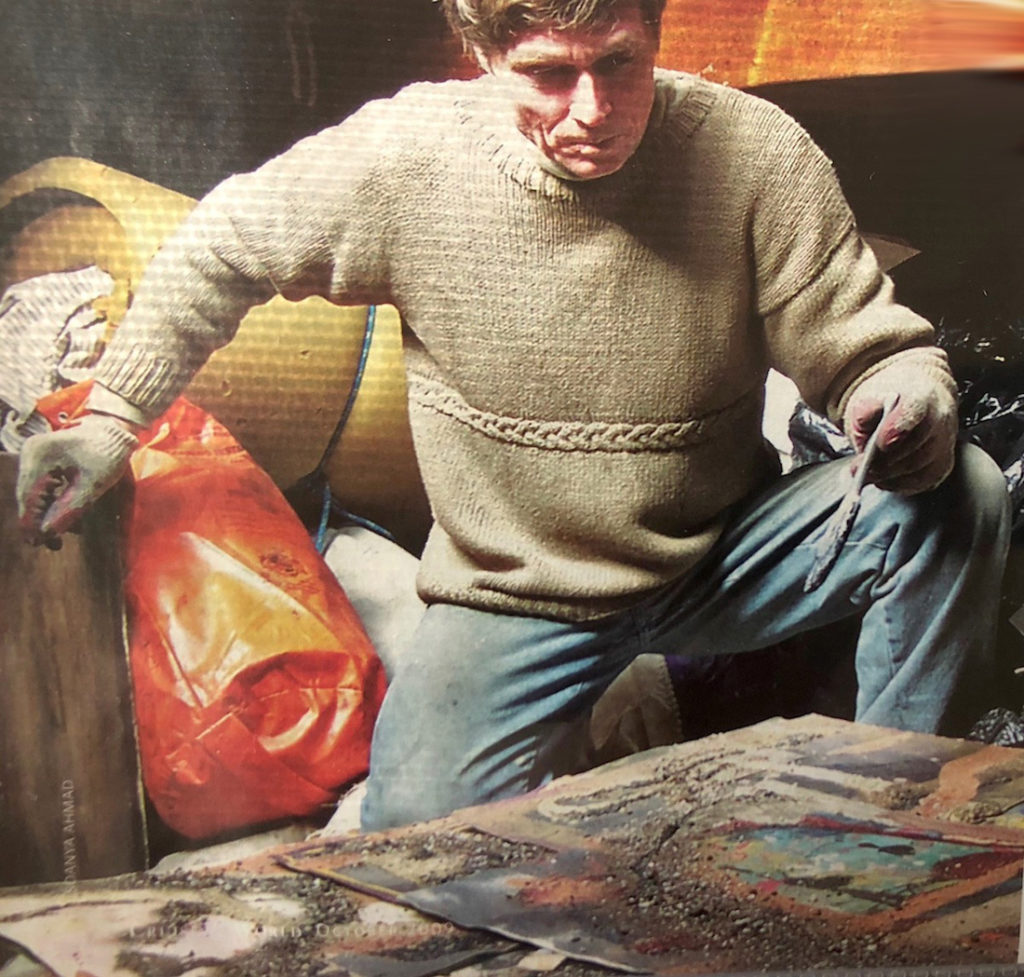

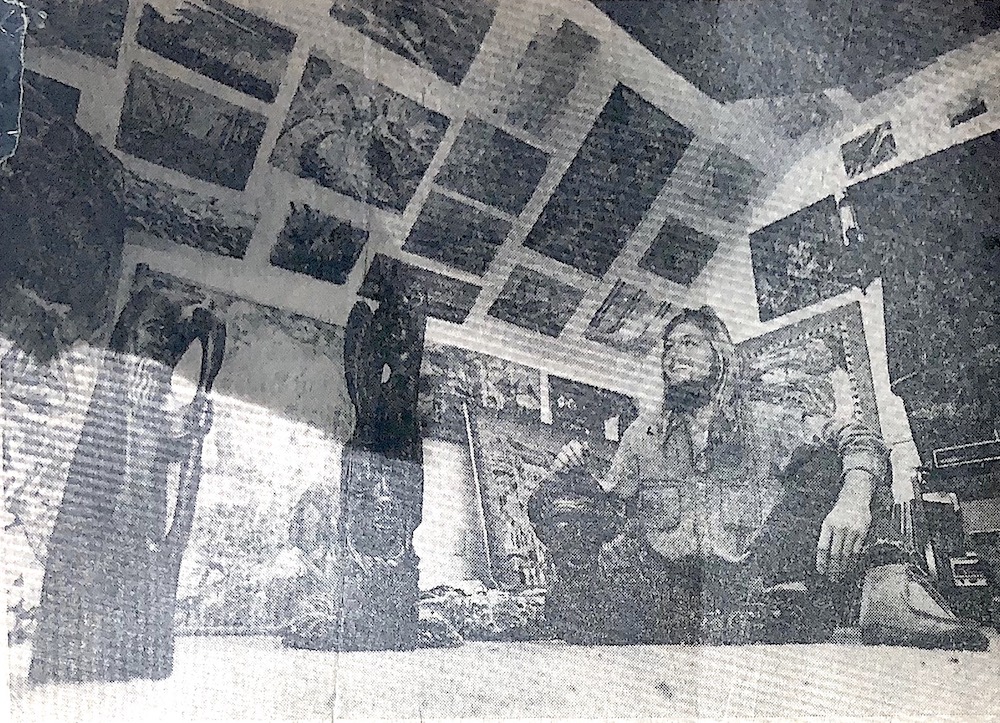

Born in 1952, the first of six children, Stowe grew up spending the summers on the North Carolina coast. With his father’s help and encouragement he learned how to build a boat. It soon became clear that he was one of those rare kids who loved spending more time on the water than the land. It was also clear that he was artistically talented. By age thirteen he was experimenting with Cubism. By seventeen his art began to take on new forms as he was drawn to discover how the paths to mysticism could be expressed as visual phenomenon. A photograph of him at 17 shows him seated beneath a large painting employing the psychedelic portraits of the Beatles created as posters by photographer Richard Avedon in 1967. He continued to stretch large canvases and experimented with multimedia, mixing oils, collage, and sometimes worn out rope from his sailboat.

The First Spiritual Voyage

In 1971, when he was nineteen, his family was not surprised when he announced that he needed to drop out of after one year in college and sail from Maui through Gaugin’s South Pacific. His trip found a turning point in Fiji after he befriended Ivo von Laake, a young Dutchman with a 19-foot plywood sloop (and no motor). While living with von Laake in New Zealand, he first learned about the most famous of French sailors, Bernard Moitessier. Von Laake had just spent a year in Tahiti helping Moitessier with his book, The Long Way (published a few years later), so von Laake regaled Stowe firsthand with the sailor’s exploits and philosophy. Stowe was particularly struck by the fact that, despite being in the lead of the historic first solo ocean race around the world, Moitessier eschewed the cash prize awaiting him at the finish line in England in favor of continuing on to Tahiti. Moitessier later explained to The London Times that he extended his voyage “because I am happy at sea and perhaps to save my soul.” Before the publication of the great sailor’s book, Stowe was struck by quotes such as, “You can take your mind off of the land and just be at sea and keep going.” Stowe clearly understood Moitessier’s meaning when he said, “You do not ask a tame seagull why it needs to disappear from time to time toward the open sea. It goes, that’s all.” This philosophical acceptance would continue to resonate as true with Stowe because he, like Moitessier, was imbued with Far Eastern religions and had discovered yoga at sea as a means of enhancing his experience as well as his art.7

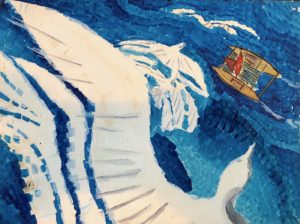

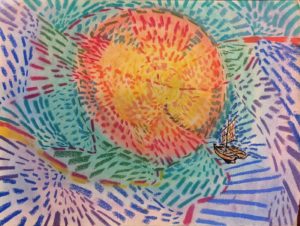

The South Pacific thus became the first breakthrough spiritual voyage for Stowe, one where he increasingly felt at one with the ocean. He captured his experiences swimming with dolphins, painting them swimming above him in the sunlight while he was simultaneously looking down at the seabirds flying below him. In another painting he expressed being awestruck by double rainbows. Stowe attributes this voyage as being “how the seeds were planted” in reinforcing the confidence needed for his own record-breaking voyage from 2007 to 2010. “Many people said I had my head in the clouds, but my life was based upon a lifetime of boat building, navigation, athletic and seamanship skills I developed. Then I was free to meditate on the sea and use my insights to go further than the men before me. In my case, I also used my lifetime of art creation to help me.” In his Flying Above the Sea Birds Looking Down on Catamaran Tantra, he states that “This painting goes with the first manuscript, begun when I started building the catamaran. It was intended to be an illustrated children’s book about the adventures I was going to go on in my little catamaran. I was two characters, the sailor and the artist. I went on many of adventures at sea creating art and meditating. We went into a space of unfamiliar shapes, and then into a rainbow void where it was revealed that we would return home and build a bigger boat to take our family and friends on a voyage to paradise. Then we returned home to build the boat. The amazing thing was that most of my fantasies came true. That book is another example of how my art programmed my future and helped me realize my dreams.”

Peter Nichols’ insightful (and often chilling) A Voyage for Madmen (2001) is the exemplar book on the physical and psychological demands of ocean solo sailing for very long periods. “Normal people aren’t driven to try to sail around the world without stopping,” he wrote. “They don’t stop their lives midstream and embrace, with single-minded effort and every resource available to them, a hair-raising stunt never before attempted and which has every chance of killing them.”8

It’s important to point out that Stowe is neither an egomaniac nor junkie of adrenalin rushes. He never had a guru or spiritual guide. He never sought a life on the ocean for personal salvation. Rather, he has always returned to the ocean for enlightenment, and this act is inseparable from his approach to making art. On his first trip through the South Pacific he brought with him books by Carl Jung such as Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1963) and Man and His Symbols (1964). Also influential on his path to self-realization was The Tibetan Book of the Dead (1927) by Walter Evans-Wentz, a Theosophist. Equally alluring was Carlos Castaneda’s very popular The Teachings of Don Juan (1968) about shamanism and mysticism. “Even more important,” says Stowe, “is Tibetan Yoga and secret doctrines because the techniques are powerful and bring on ecstasy for me more than ideas or teachings.” Today, the numerous art books on Stowe’s bookshelves are joined by titles on Far Eastern Buddhism, Zen, astral projection, metaphysics, magic, esoteric psychology, yoga, and the universe — all pointing to his holistic exploration of creativity and the unconscious. In Imagined Catamaran he uses ‘imagined’ in the title “because I had not yet built the catamaran. I even put a Chinese Junk type sail, which I never ended up using. This painting also goes with the children’s book.”

First Crossing of the Atlantic

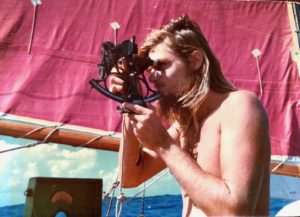

As a result of his year in the South Pacific, Stowe became increasingly drawn to emulate Moitessier in both philosophy and spiritual approach. He soon planned his next adventure on the high seas. After hitch-hiking from Arizona to his grandfather’s beach house on the Intracoastal Waterway near Shallotte Point, North Carolina, he passionately explained his need to build a boat that could cross the Atlantic Ocean. Once again his family supported his dream, and for the next eight months he focused on building a 27-foot catamaran with red sails he named Tantra. In the summer of 1973 von Laake rejoined Stowe (now 21) and the two young men launched into the North Atlantic. The media was captivated by the daring adventure, reporting that there was no motor and only a sextant for navigation.

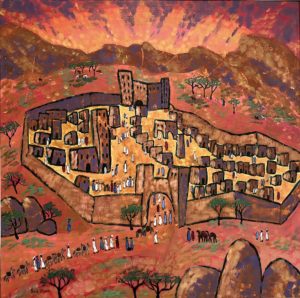

After arriving in Portugal, von Laake returned to Holland and Stowe continued to sail solo to the Moroccan coast. He described this solo ocean voyage as, “a young man’s life or death rite of passage into a modern sea shaman.” Settling in Mogador (now called Essaouira), he met a spiritual healer in a tea shop who told him stories about his practice of laying on hands. Using the tea shop as his base, Stowe was inspired to paint many colorful scenes of life in the coastal town.

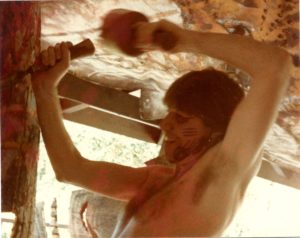

Von Laake rejoined Stowe after three months and they crossed back over the Atlantic, this time arriving in Bahia, Brazil. Because both young sailors went into deep meditation while they created art at sea, Reid titled this voyage, “Two Together as One into the Void.” From Bahia they continued north and then up the Amazon River where they set anchor and went ashore. Stowe collected abandoned canoes and carved them into mermaids and yoga goddesses and ceremoniously sacrificed them to the sea.

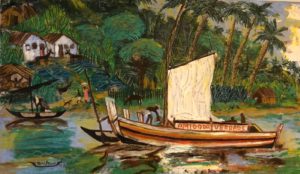

He also painted on sails and charts his proposed routes with self-portraits on the other side cheering, “Hooray, I made it!” These paintings not only translated his experiences of the Atlantic crossings, but he considered them to be “programming paintings” that would help him succeed at sea in the future. Stowe recalled painting Amigo Da Verdade: “It rained hard throughout the morning. We meditated, did yoga, and gazed down through our slatted deck at the fish congregating under the catamaran. When the rain stopped the animals and the people came out and began their activities. I made this painting at that moment.”

The pair parted again when the opportunity arose for Stowe to help a Frenchman sail his boat to Martinique in the Caribbean. However, while sailing out of the broad Amazon River delta at night they were captured by pirates and robbed of all their valuables. The pirates asked about the little catamaran that was anchored nearby on the river but Stowe said he knew nothing about it. The pirates argued about whether to kill them, but eventually decided to leave them hog-tied on the sailboat. After being prisoners for three nights and two days, they managed to untie themselves and during a storm at night tacked out of the mouth of the Amazon. That morning a mahi-mahi jumped into the air, rang the ship’s bell, and fell into cockpit. They realized it was Thanksgiving Day, and the sea gods had confirmed their good fortune. The region remains dangerous. In 2001, a group of pirates shot and killed New Zealand’s most famous sailor, Sir Peter Blake, in the same area.

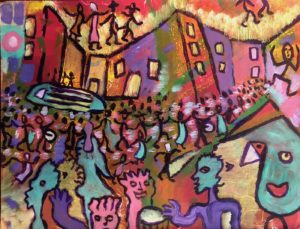

Carnaval in Salvador is part of a group that Stowe painted during the voyage and were meant to illustrate his manuscript, The Voyage of the Lightship Tantra (written 1973–75). He describes the book as “The story and loves of a young man who sails the smallest boat to four continents doing yoga, painting, and becoming the shaman of the sea. The highlights are losing the boat to pirates and returning to the Amazon, rescuing the catamaran, and later sailing a boatload of pot back home with plans to build the magical Tantra Schooner (later renamed the Schooner Anne).”

Stowe in the Amazon

In 1974 luck smiled upon Stowe again when an adventurer on the Amazon sent a letter saying that Tantra was spotted still anchored in the delta. Stowe returned, stealthily slipped aboard at night, and quietly sailed his catamaran out of the Amazon. In the Caribbean, he arrived at the then sleepy Port Elizabeth on the island of Bequia. To his delight he discovered the island was a haven for sailors and he settled in painting many canvases, usually on worn sailcloth. He also discovered that many of the sailors were earning significant amounts of cash to support their wanderlust by smuggling boatloads of marijuana to the American shore. And then the big idea hit him. He was the most experienced ocean sailor of the lot. If he worked hard and saved all that money he would have enough to fulfill his dream of building a large schooner to make the longest voyage at sea. Stowe soon became known to the Colombians. He accepted the challenge and quickly made a reputation as a reliable captain in the Caribbean.

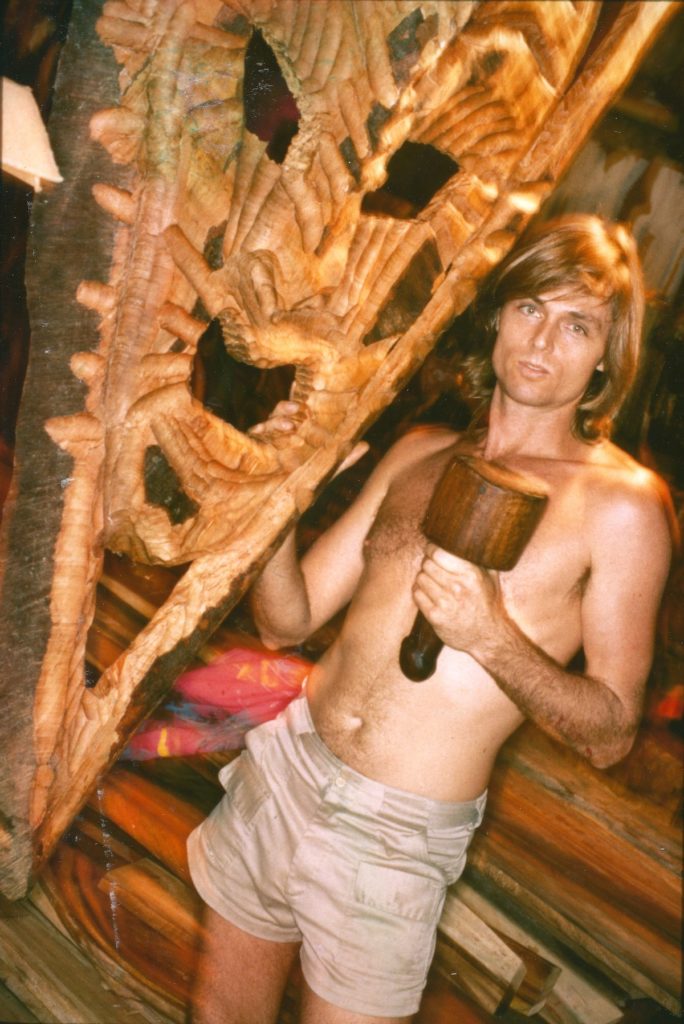

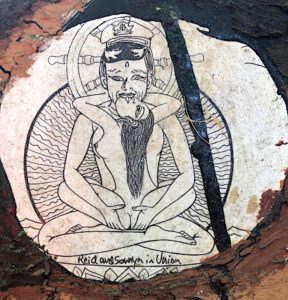

The woodblock at right illustrates one of Stowe’s encounters with pyschotropic mushrooms. The wood he used was “purpleheart,” which is a very hard, durable, and water-resistant tropical wood. It has always been one of Stowe’s favorites, and he used it to carve the rail all the way around the Schooner Anne as well as the sea serpent figurehead off his bowsprit and in the interior flooring. After the long voyage, Stowe and Soanya returned to Guyana to repair the schooner and it took them months to acquire it. “Painting is my true love,” he says, “but I have had so many mystical experiences with tropical woods absorbing, carrying, and resonating spirits.” We surfer sailors knew that after a big rain for a few days the magic mushrooms would grow in cow pies. We also figured the surf would be up in the calm after stormy weather. So, we carried our surfboards over the hill to our favorite beach where no one lived and passed through a big cow pasture. There were mushrooms everywhere. The locals called them Jumbi Umbrellas and were afraid to eat them. A Jumbi is a mischievous forest spirit in the Carib-African Voodoo culture. I found a place where the farmer had raked the manure into a giant pile and it was covered with mushrooms. I climbed on top, squatted down, and started picking and eating them. Then we went surfing. It was an enlightening experience. We saved a lot for our friends, but they do not taste good later because they quickly wilt and turn brown.”

Pot Smugglers of the Caribbean

I’ve done a bit of smuggling,

I’ve run my share of grass,

I made enough money to buy Miami,

but I pissed it away so fast

Never meant to last,

never meant to last.

— Jimmy Buffet, 1974, “A Pirate Looks at Forty”

For Stowe, pot smuggling became a way to earn a living, just as pot farming today has become a multi-billion-dollar enterprise. By the end of 1977, he had the money he needed to build his schooner, and a year later he completed the construction. He even got married — to an artist, Iris Groskoph.

Moitessier would have been intrigued if he had known that Stowe carefully studied the construction of 19th-century American schooners and concluded that the Gloucester fisherman was the quickest and the most seaworthy sailboat. He even went to Mystic Seaport and studied the complicated ropes and pulley plans for its famous schooner, the L.A. Dunton. From time to time Stowe would climb atop his neighbor’s roof to get a better perspective on how the schooner was taking shape, and then slightly bend the steel rods used in its construction until it was just right. Stowe describes his schooner as being “round like a bottle, with a deep keel, so it floats like a duck in rough seas, and cuts through the water like a submarine.” With family pitching in, by the end of the summer Schooner Anne was launched from the same North Carolina shore where Stowe had built Tantra just six years earlier. A year later his daughter, Viva, was born. For the next two years the young family explored the Caribbean in their 70-foot, 50-ton ocean home. The island of Dominica was a favored port of call because this is where Stowe collected most of the tropical hardwoods from which he carved sculpture and made furniture.

The 1980s was a fruitful decade for Stowe in painting but after the couple separated the island of St. Barts held particular attraction for him. There he became friendly with Basquiat and soon thereafter rented a loft in SoHo and the two often got together. “I liked Basquiat a lot. He even painted life-size portrait of me, inscribed my name above my head, and gave it to me,” recalled Stowe, “but he was always trying to score heavy drugs and that was not my scene.” Stowe was more focused on scoring art materials discarded by frustrated painters. As a “beachcomber in SoHo” he found a steady supply on the sidewalks. This explains why his paintings sometimes bear the signatures of other artists on their versos.

Another artist with whom Stowe became friendly in St. Barts was singer Jimmy Buffet. “I met Buffet in St. Barts in the early 1980s when everybody was partying together. We got to know each other well enough that he said he wanted to write a song about me. But recently I heard he was distancing himself from his old smuggling buddies. Maybe now as pot is being legalized he might reidentify himself with the St Barts sailing smugglers, because it was all colorful good vibes.”

I used to rule my world from a pay phone, And ships out on the sea,

But now times are rough,

And I got too much stuff,

Can’t explain the likes of me.

— Jimmy Buffet, lyrics from “One Particular Harbour” (1983)

Envisioning Art through living the disciplines of Buddhism, Yoga, and the Tantras

It’s important to clarify that Stowe saw pot-smuggling as the means to raise the money necessary to build his schooner. His own use of pot or psychedelic drugs was not out of a desire to become lost in space. Rather, he learned that the proper use of mushrooms and marijuana were a means to attain knowledge of the sacred, which was as a path to enlightenment. “Throughout the long story of man, marijuana and other mind-altering drugs were used sacredly as a sacrament for various purposes,” he says, “It is the phrase ‘recreational’ that sets the future of pot up for unenlightening experiences that lead to problems.” When Stowe did smoke pot it was always in the Buddha pose meditating or practicing yoga. Consistent with this philosophy of connecting to higher powers was his adoption of the Tantric traditions for transmuting and lifting his sexual drives into spiritual energy.

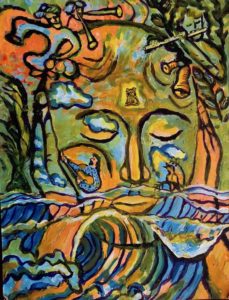

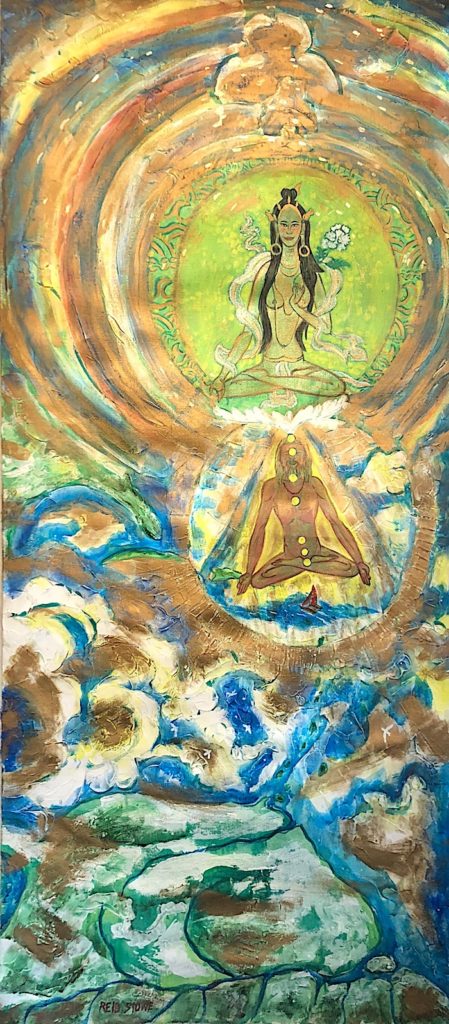

About The Nirvanic Symphony:

“This painting, like all the others from 1970–75, is an illustration of my mystical experience of listening to the music in my head. When Ivo and I sailed south of Morocco in heavy winds we were nearly flipped over as we surfed down one wave, plunged into the back of another wave, and water sprayed in our air vents. Days of stormy winds, waves, and wetness are quite hectic and stressful. I relaxed in my narrow bunk with the waves pressing the thin plywood hull against my shoulders on both sides and put my hands over my ears. As the painting shows, there I am sitting in the lotus posture in my third eye with big ears, implying I am listening. The sound of the waves is most dominant. I also hear the music of my friend Ivo who plays the silver flute. I hear Moroccan music, birds, and bells, and Carlos Santana’s guitar — it all blends together into beautiful music.”

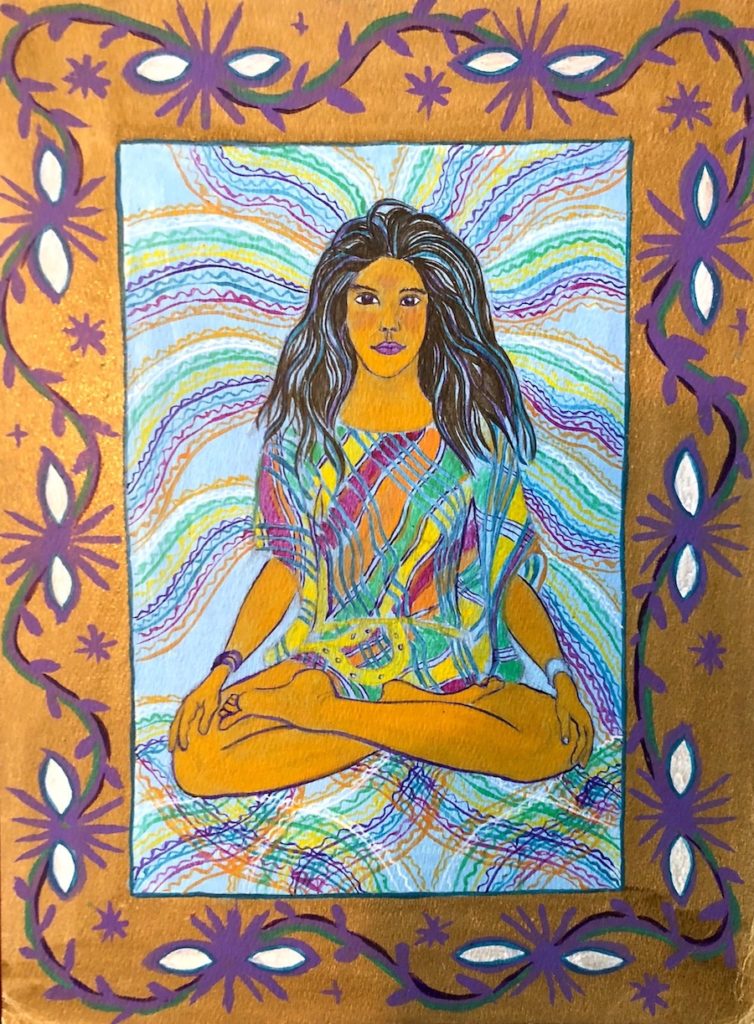

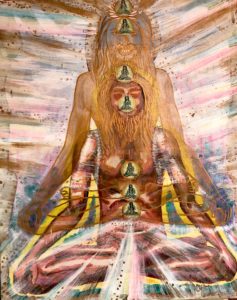

About Meditating with the Green Goddess in My Chakras:

“These paintings are very important for me because they were painted to protect and enlighten me in dangerous conditions. I have many more of them as big as 12 x 15 feet. This painting is a graphic example of one of my practices. At 23 years of age I was preparing to go back into the pirate’s territory and rescue my catamaran, Tantra, so I made this painting and others to give me the courage and the spiritual power to succeed.

The premise of my Yoga Adventures at Sea manuscript is that painting and sculpture has been an important part of many of the Yoga disciplines in Buddhist and Hindu cultures since ancient times as well as the Japanese Shinto. Of course, this goes back to man’s most ancient art in caves. So, when I speak of yoga, this includes my art practice. My depictions of real experiences at sea carry the utmost validity because of my success of achieving what no other man may be capable of surpassing — physical acts in a life-and-death environment where by I departed the touch of the earth far longer than any human. After Soanya had to depart I spent 846 days without seeing land or another human.

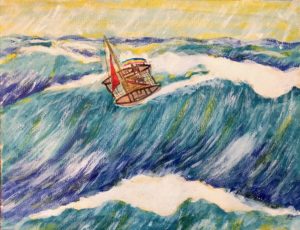

About Catamaran Tantra Smashed by Giant Wave:

About The Green Goddess Looks Over Me as I Sail Back Home to North Carolina:

The Pilot House

“The pilot house is the most important and most used room on the schooner. For cold, stormy, or even hot wet spray conditions, the pilot house is the most comfortable place to be and still see 360-degrees and keep an eye on the sails through the skylight. Knowing that the schooner would spend its days in the void of the sea, I wanted the interior to have an inspiring wonderland of rich tropical carved woods that would contribute to the well-being of the crew. Feeling that I sail on the cathedral of the sea, I wanted the interior to have a spiritual uplifting theme that would actually help us through long days. Practically, the pilot house is right above the motor room and serves as a work shop/art studio, with navigation table, tool trunks, work stations — and there is a bunk and places for eight people to sit together for meals. There has always been a wood/coal stove in the back of the pilot house. I only used the motor coming on and off the dock. I never have used the motor at sea, but it is very important to be able to maneuver into tight spaces.

In 1979 we sailed to the Caribbean with a full cargo, but with nothing built in the interior because I always intended to use tropical woods. We were in Bequia when Hurricane David, one of the deadliest hurricanes of the century, made a direct hit on Dominica, about 150 miles north of us. Afterwards, we sailed up to Dominica, which is a mountainous island. Huge trees had been toppled and there had been many landslides. Natives with chain saws salvaged these rare woods and we bought from them and traded food and goods. They loaded us up with teak, mahogany, and at least ten other beautiful woods, which we only knew by their Creole names, such as Bois Lézard, Maho La Mer, and Kowosol. I used these for the whole interior, including the pilot house with my twenty carvings of spiritual, nautical, and nature themes. All have all contributed to the magic and rich history of the (Tantra) Schooner Anne.”

The First Arts and Cultural Expedition to the Seventh Continent

Moitessier’s epic achievement of the longest non-stop sea voyage in history never left Stowe’s mind. In 1986, while in New Zealand, he revisited the concept of challenging that record. Just how long should he sail? In his mind’s eye he saw a slot machine spinning until it stopped on 1,000. Soon after, this number was reinforced when he read that it would take about 1,000 days for astronauts to travel to Mars and back. From the beginning, he conceived of recruiting a crew of eight because he was acutely aware of the extreme difficulties of handling a big schooner on his own. He also wondered how isolation in a dangerous environment would affect the crew’s coping with physiological and psychological deprivations. He knew that on the ocean any mistake could mean death. Moreover, he wondered how such an environment would affect his own creative drive. NASA had been wondering the same thing. Stowe then named his mission “1,000 Days at Sea: The Mars Ocean Odyssey.” To begin, he conceived of a five-month test voyage that would further prove his abilities and reinforce his presentation to prospective sponsors. He chose Antarctica for its notoriously dangerous passage near Cape Horn. Knowing that isolation would come into play, he recruited a mixed bag of artists, musicians, writers and comedians. “I wanted to bring a creative group,” he said, calling the voyage “The First Arts and Cultural Expedition to the Seventh Continent.” He also called it “The Antarctic Jokers Expedition” because the group of seven were inexperienced sailors who saw themselves a entertainers.

Early in 1987, the difficult task of securing corporate sponsors met with mixed success. He started by joining the prestigious Explorers Club in New York, discovering that most of its members were not really explorers. The club proved to be the first of many prospective funders whose initial enthusiasm eventually revealed an aversion for risk.

“The club’s expeditionary committee gave Stowe $2,000 in seed money, a high form of sanction, and NASA has shown interest in his voyage. But most club members, the president among them, thought his plan a prescription for disaster. “I half expect to see a headline a year after he leaves that says, ‘Two Found Murdered’” said president Nicholas Sullivan, who supported Stowe’s flag award. “But if he makes it, he’ll be one of the greatest explorers ever.” Most members were fond of Stowe, Sullivan said, and it was easy to see why. He had pluck. ‘Before I bring the boat back to port,’ Stowe vowed, ‘I’ll have to go crazy.’ It was rare to encounter such impetuosity and unbridled passion around headquarters.” 9

After negotiating ice packs in hurricane force winds, the Schooner Anne made stops along the Antarctic Peninsula and presented art and entertainment to the groups living on scientific research bases. Eventually, their disruption would cause the base directors to ask them to move on. When they set anchor in Whaler’s Bay at Deception Island they were actually in a caldera, the center of

an active volcano. After it had erupted in 1967 and again in 1969, heavily damaging the local scientific stations and causing the British abandon the island. All that remained was a row of rusted abandoned whale oil tanks standing along the shore, remnants of the island’s old role as a whaling station. Whale bones still littered the beach, sad reminders of an inhumane industry. Stowe became inspired to affix paint rollers to long bamboo poles and painted 20-foot-tall graffiti faces on five of the tanks. The huge primitive faces stood as sentinels, tribal warriors with eyes wide and glaring, and mouths aghast at man’s brutal intrusion on this remote part of the earth. A few years later, travel writers for Islands Magazine wrote about the mysterious graffiti faces they encountered, unaware of the identity of their maker.

Scientific illustrators and topographic artists had visited Deception Island since the early 19th century, but Stowe’s fiercely expressive graffiti faces unite animism and environmental issues and are the first artworks on Antarctica. As such, they represent the birth of a new art and myth on the

Southern Continent. “These are the biggest paintings that stand alone and the farthest from any others in the world,” says Stowe. He may also be the first to carve sculptures in this inhospitable environment, including his six-foot tall mahogany The Penguin King.10

Changing Tides

Son of a son, son of a son,

son of a son of a sailor,

Son of a gun;

load the last ton

One step ahead of the jailer

— Jimmy Buffet, lyrics from “Son of a Son of a Sailor” (1978)

One early morning twilight in 1993 Stowe suffered a setback. A team of special agents from the D.E.A. descended upon his loft in SoHo and used their battering ram to break down the door. Unaware that he was “one step ahead of the jailer,” he was arrested, not for his private pot-growing rooms, but for the 100 tons of the weed he had helped smuggle into the country. Even though he had abandoned that daring business at least five years earlier, recently captured dealers accepted a plea bargain and turned on him. Stowe was dispatched to federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas. For nine months he immersed himself in reading, writing, and yoga. He did not paint, nor did he let on that he was an artist because he feared being pressured by inmates to paint portraits of their girlfriends from photographs.

One early morning twilight in 1993 Stowe suffered a setback. A team of special agents from the D.E.A. descended upon his loft in SoHo and used their battering ram to break down the door. Unaware that he was “one step ahead of the jailer,” he was arrested, not for his private pot-growing rooms, but for the 100 tons of the weed he had helped smuggle into the country. Even though he had abandoned that daring business at least five years earlier, recently captured dealers accepted a plea bargain and turned on him. Stowe was dispatched to federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas. For nine months he immersed himself in reading, writing, and yoga. He did not paint, nor did he let on that he was an artist because he feared being pressured by inmates to paint portraits of their girlfriends from photographs.

Upon his release in 1994 Stowe spent the next two years rebuilding the Schooner Anne in St. Maarten where she had been moored since 1987. It’s important to point out that even during his smuggling days Stowe had constantly produced art. After his release some of his big paintings on sails contained messages aimed at helping him to overcome the bust and to succeed on his next voyages. One read “It’s OK Dream Smuggler” in letters tapering into the distance. Still planning ahead for the “1000-day Voyage,” when the repairs were finished in 1995 he returned to the ocean, this time to practice with newly-built self-steering gear. He assembled a crew of seven to that included his new French wife, Anne-France Peidfer, and teenage daughter, Viva. When the arrived at La Rochelle, France, Stowe docked next to Bernard Moitessier’s famous sloop at the Musée Maritime de La Rochelle, located, of course, at Place Bernard Moitessier. Again, the spirit of Moitessier reminded him of the ultimate challenge. However, raising money for either an epic voyage or even repairs proved fruitless for one branded as an ex-convict. Anne-France pressured him to be realistic and sell the boat and instead buy a farm in France. That’s when the marriage ended. Rebounding in 1997, he met another adventurous French woman, Laurence Guillem, who would become his third wife. Together, they embarked from France to the South Atlantic, far off the coast of Brazil on a winding voyage to New York he named “100 Days Non-Stop at Sea.” Stowe had rigged pulleys on the deck, passing lines through winches that lead to the cockpit. In tandem with the self-steering gear, this rigging enabled him to sail the schooner by himself for the first time. In the summer of 1998 they sailed up the Hudson River and docked at Pier 63 at 23rd Street.

In 2001, Stowe kept the momentum going for the “1,000 Day Voyage” by returning with Laurence to the South Atlantic on an art project he called “The Odyssey of the Sea Turtle.” For 194 days without touching land he created the first-ever GPS art (global positioning satellites) on the ocean. He navigated in such a way that his GPS tracker drew his course in the shape of a sea turtle, and he viewed this art as “a healing contribution to the world.” Stowe traced his primary sources of inspiration for GPS art as beginning with the ancient Nazca Lines, those mysterious zoomorphic geolyphs in the desert of southern Peru that are so large they can only be seen from the air. Also influential were the many long walking expeditions of his British peer, Richard Long, the land artist who charted lines documenting his many long treks throughout the world during the 1980s. Stowe was also influenced by Long’s later canvases, which used earth, stones, and mud collected during his walking expeditions. Stowe  incorporated into his paintings earth, sand, saw dust, and wood chips collected from his sculptures in found tropical woods. These elements of the land in his paintings kept him healthy in an ocean environment of corrosive salt. In addition, ever since the mid 1980s, when he had become committed to “departing the touch of the earth far longer than any human since we evolved” he made it a practice if bringing buckets of earth aboard the schooner. He would periodically sink his feet into an earth-filled bucket to balance his spirit and physiology, making him feel grounded with Mother Earth.

incorporated into his paintings earth, sand, saw dust, and wood chips collected from his sculptures in found tropical woods. These elements of the land in his paintings kept him healthy in an ocean environment of corrosive salt. In addition, ever since the mid 1980s, when he had become committed to “departing the touch of the earth far longer than any human since we evolved” he made it a practice if bringing buckets of earth aboard the schooner. He would periodically sink his feet into an earth-filled bucket to balance his spirit and physiology, making him feel grounded with Mother Earth.

The 1,000 Day Voyage

As the years passed, the task of assembling a crew for “1,000 Days at Sea: The Mars Ocean Odyssey” continued to prove as daunting as raising funds. Laurence urged him to sell the schooner and move to the country. Equally predictable, they divorced. Undaunted, in 2003 Stowe launched a recruiting trip he aptly called “The Search for the Argonauts.” But the qualifications were quite high. After all, he was not necessarily seeking people with sailing experience who loved the ocean as he did. He sought people who wanted to sail into the void, into eternity, into the place everyone must face in the end. He was testing to discover others who held a fearless affinity with mythical beings. Each of his most experienced sailing buddies perceived the trip as far too dangerous. Predictably, his less experienced sailor-friends, who were at first naively enthusiastic for the adventure, backed away when they, too, were warned of the magnitude of the risk. To make matters worse, every expert his prospective investors had consulted concluded that the probability of failure was exceedingly high.

Ultimately, Stowe found himself alone — except for Soanya Ahmad. She was a recent graduate of the City University New York who was conducting a photo-documentation of the New York City waterfront and first met Stowe tending to his schooner at Pier 63. Until this point many readers may have misperceived Stowe’s mission as that of a madman artist-survivalist sailor seeking to set an endurance record. Like Moitessier, Stowe distained records and saw the themes of survival and endurance as contrived. Instead, he saw that in the natural course his own evolution had arrived at the place where he could succeed in carrying out his aspirations. His life picture was much larger now, and he said, “I was looking at how I could help humanity evolve.” Coincidentally, this story turned into a love story between an artist and his muse. Stowe found in Soanya an indefatigable champion and soulmate who was the catalyst whose faith in the seemingly impossible mission ensured its success. Together, they were at once alchemists and realists who refused to let the deadly risks obscure their quest of discovering the magic and mystery of the oceans. They saw themselves as a joined human consciousness heading into the unknown, shifting away from the earth, and evolving to higher realizations on what would become the longest sea voyage in history.

During the next three years the couple secured donations from food suppliers and restaurants. Every spare space in the hull of the Schooner Anne was packed with donated foods, including rice, beans, tomato sauce, pasta, and fine pesto, olives, and chocolate, all carefully double-wrapped in vacuum-sealed plastic and placed in waterproof containers. Ahmad also brought along some of her favorite Indian spices, such as cumin, curry, and masala. Other provisions included coal and firewood for the iron heating stove. The big mahi-mahi or tuna he caught were then salted and dried and became meals until it became time to catch another. A system for collecting rainwater used tarps and sails, and an emergency desalinator was brought to make seawater potable. The deck was outfitted with solar panels for powering the electronics onboard, which included a laptop and a satellite phone.

The “now or never” day arrived on April 27, 2007, and the couple launched from a dock at Hoboken, New Jersey. Just fourteen days out, while crossing the major shipping lane, the voyage nearly ended when a freighter struck a glancing blow that sheared off the bowsprit. The bowsprit protruded fifteen feet off the bow and its forward fourth sail had played a crucial role in controlling direction. Knowing he would be unable to sail without the bowsprit against the wind, Stowe struggled to create a jury-rigged system. He wrapped two heavy chains around the bow and attached them to the giant forward turnbuckle, holding the whole rig forward. He wound up sailing the entire voyage in this disabled condition.

Soanya quickly went from being a completely inexperienced landlubber to one who soon overcame seasickness and absorbed all of Stowe’s coaching. However, after ten months she became increasingly ill. As the Schooner Anne approached Australia, Stowe emailed the one man he knew would help: Jon Sanders of Perth — the very man who had broken Moitessier’s solo record. Sanders now happily obliged by sailing out of Perth and picking up Soanya at sea. In this love story it turned out that she was not seasick but pregnant. Moreover, she had just logged 306 days at sea, setting the longest non-stop record at sea for any woman and the longest sea voyage in history for a couple. Despite her insistence that Stowe continue his quest, the media painted Stowe as a narcissistic kook and major pot smuggler who abandoned his pregnant lover. Weekend yacht club sailors used the blogosphere to try to scuttle his credibility, doubting the voyage was even happening. Fortunately, NASA’s satellites had been signed on with a tracking company that monitored the next three years of sailing. “I suddenly became the Hated Man,’ he says. “The National Geographic told me, ‘We can’t cover your story because we’ll have a public backlash.’”

During the voyage Stowe wrote several hundred essays, and his more esoteric thoughts appear in the unpublished manuscripts — Yoga Adventure at Sea and Illuminations from the Longest Sea Voyage in History. In one near-death experience, a crushing rogue wave capsized his schooner in the infamous “Roaring Forties” near Cap Horn. That experience contrasted with being serenaded by a pod of whales. Stowe lived in a dichotomy where he remained acutely aware that any mistake on the ocean could mean death yet he fully embraced each day’s experiences as transcendental. When the seas calmed he painted and sculpted, never feeling like a prisoner in solitary confinement, but appreciating and making the most of what he saw as eternal moments. Both psychologists and physicians have long asserted that long periods of isolation deprived of meaningful human contact often leads to anxiety, high blood pressure, lack of sleep, paranoia, a break-down of the immune system, and even dementia. Stowe was having none of it. He never exhibited signs of profound irrationality — nor did he underestimate the power that was driving his spirit to both survive and be creative. With practical calm he asserted, “I was always captain on my own magical boats that I built with my shamanistic powers. I was a not a passenger or crew being taken care of by someone else.”

In Stowe’s paintings aboard ship and later in his studio his natural approach was to dissect the many “isms” in painting history, a practice he had engaged since his teenage years when he admired the planar shapes of Stuart Davis, Charles Sheeler, and the early work of Ad Reinhardt. Some of Stowe’s paintings possess the vocabulary of a surrealism. He creates stage-like settings with foregrounds upon which pointed obelisk-like spires rise up, casting shadows deep into the painting. The spires are appear as actors on stage, playing the role of optical devices that shift the viewer’s consciousness to explore a complex maze of shapes, lines, and colors. Sometimes we are invited by a beach in the foreground (with real sand) and a blue horizon in the distance — think Dalí — but passing between them can prove convoluted with linear geometric structures lurking among the layers. Shadows in spraypaint often appear, adding illusory depth to long brushstrokes. While André Mason reinforced Stowe’s use of sand it was Antoni Tàpies and Anselm Kieffer who gave him the freedom to make larger earth-filled areas in his works. The spirit of Arte Povera gave him the freedom to paint or construct on any ground support and leave it rough. Throughout, he was influenced by Tantric and Buddhist art, and sometimes mandalas are incorporated as graphic elements. Equally important to Stowe the shaman, his lifetime of yoga practice enhanced a sense of clairvoyance and gave him the confidence that his art was helping him to accomplish his dream-like mission on the oceans.

Far Beyond Performance Art

Stowe’s ocean odyssey provided more than just a wellspring of inspiration. He saw the art he created while at sea — paintings, carved wooden sculpture, and performance art — as necessary for his survival. As a ritual in pleading for protection to whatever spirits commanded the tides and the winds, he hoisted carved wooden anthropomorphised totems up his masts. On calmer seas he wore masks that he created, painted his body, and performed shamanistic dances naked on the deck. He also painted on torn sails that could no longer bear another round of his repeated sewing and mending.

This brings up his Performance Art. During the last quarter of the 20th century its practitioners were often perceived as free-wheeling cousins in the fine arts who were alternately eccentric, entertaining, or even amusing. Art critics lauded these performances as explorations of human identity — and those that pushed the limits of physical and mental stamina were soon called Endurance Art. For days or even months, and often before large audiences, these artists endured various forms self-imposed pain, solitude, hunger, or tedious rituals. Stowe was well-aware of the danger associated with Performance art on the ocean. In 1975, Bas Jan Ader, a well-regarded conceptual artist and sailor, launched his 13-foot sailboat from Cape Cod, bound for Europe. This was his most ambitious Performance piece, and he called it “In Search of the Miraculous.” His body was never recovered.

Stowe’s considers his ritual of “Dragon Dancing” crucial to his survival at sea. “When I wear a dragon mask and dance, I go into a trance and then receive illuminations like no captain or man before me,” he said. “When sailing to Antarctica or alone on the 1000 Day Voyage I am always in a life-or-death high-performance situation. I must do what I can to empower myself, receive illumination, and become one with my environment. It’s not about having a great idea about acting or performing. I still trance dance in my studio while I paint.”

A Lifetime of Dragon Dancing

“Willed introversion, in fact, is one of the classical implements of creative genius and can be employed as a deliberate device. It drives the psychic energies into depth and activates the lost continents of infantile and archetypal images. The result may be disintegration of consciousness…but on the other hand, if the personality is able to absorb and integrate the new forces, there will be experienced an almost super-human degree of self-consciousness and masterful control. This is a basic principle of Indian Yoga. It has been the way, also, of many creative spirits in the West.”

— Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p.53

Stowe on Dragon Dancing:

“If I said I’d been dragon dancing for most of my life, I wouldn’t be exaggerating. Nor would I be unique among the people of the world. Have a look at the history of man. From the very beginning people have been dancing even before we became what is now called human. Perhaps our deep archaic memories surface as we remember the elaborate mating dances we did when our ancient spirit resided in the reptiles, birds, insects, and sea creatures before we crawled out of the eternal abyss. These are the feelings that come to me as I dance. Even as children we danced like animals, roared and made noises. I dance like all these creatures and in my imagination colors flicker phosphorescent in kaleidoscope patterns as my cosmic opposite and I trade moves. I think anybody who has danced into a heat can relate to what I’m saying. Mysterious things happen to our psyche even on a sawdust cowboy dance floor. But imagine what it is like to wear a dragon mask and dance naked on the wide-open eternal seas far from all of civilization after not having seen another person for years. This is real dragon dancing in a shamanistic, ritualistic, ecstatic sense very similar to dance that still goes on today. I think people the world over dancing in a night club for hours to loud amplified music are experiencing a form of transcendence that all people long for deep in their psyches.

The Whale

Halfway across the South Pacific, Stowe realized that he would find himself amidst the infamous “Roaring Forties” around the perilous Cape Horn in winter. In order to avoid freezing he changed course and stalled for forty days, drifting and meandering northward as he neared the Galápagos Islands. “Jesus fasted for forty days in the desert and there are 40-day mystical experiences in other religions,” says Stowe. “So, I decided to do a 40-day drift in whatever direction the wind sent me.” Then an old smuggling buddy who was following Stowe’s automatic GPS tracking system told him that his unplanned path appeared to partly delineate the shape of a whale. “I changed course immediately to draw the flipper and make the whale more accurate,” he said. At first, it appeared that any GPS drawing would be impossible because the accident with the freighter had left the schooner out of balance. He was forced to crank hard on the wheel just to hold a course. This not only caused drag but he lost of the ability come to windward. However, after nearly two years he had become proficient in adapting to this disabled condition. The finished GPS Whale took forty days. “That was the high point magical moment of the voyage. I was empowered by the experience of The Whale to do whatever I wanted. Then I knew nature and the Gods were looking after me and I would succeed.” Nevertheless, after Stowe rounded Cape Horn his schooner was hit by a giant rogue wave and turned upside-down. Fortunately, the bottle shaped hull of the Schooner Anne caused her to right herself. Stowe was hurt, and the schooner was damaged, but he managed to make repairs and continue on.

Halfway across the South Pacific, Stowe realized that he would find himself amidst the infamous “Roaring Forties” around the perilous Cape Horn in winter. In order to avoid freezing he changed course and stalled for forty days, drifting and meandering northward as he neared the Galápagos Islands. “Jesus fasted for forty days in the desert and there are 40-day mystical experiences in other religions,” says Stowe. “So, I decided to do a 40-day drift in whatever direction the wind sent me.” Then an old smuggling buddy who was following Stowe’s automatic GPS tracking system told him that his unplanned path appeared to partly delineate the shape of a whale. “I changed course immediately to draw the flipper and make the whale more accurate,” he said. At first, it appeared that any GPS drawing would be impossible because the accident with the freighter had left the schooner out of balance. He was forced to crank hard on the wheel just to hold a course. This not only caused drag but he lost of the ability come to windward. However, after nearly two years he had become proficient in adapting to this disabled condition. The finished GPS Whale took forty days. “That was the high point magical moment of the voyage. I was empowered by the experience of The Whale to do whatever I wanted. Then I knew nature and the Gods were looking after me and I would succeed.” Nevertheless, after Stowe rounded Cape Horn his schooner was hit by a giant rogue wave and turned upside-down. Fortunately, the bottle shaped hull of the Schooner Anne caused her to right herself. Stowe was hurt, and the schooner was damaged, but he managed to make repairs and continue on.

Stowe’s time for painting was conditioned by the weather. For long stretches through severe weather and high seas his time was consumed by maintenance and survival. Even fair days would begin with the never-ending tasks of cleaning, fixing equipment, adjusting rigging, and patching shredded sails. “One leak left unattended or too many torn sails,” he said, “and you could suddenly be in serious trouble.” Art time was reserved for after a lunch of nuts he roasted or sprouts he grew. “The absolute key to my diet, the real secret to what has kept me going all these years, is sprouts. They give you way more fresh food and grow much faster than regular gardening.” After many hours painting or sculpting, he would practice yoga and meditation for a few hours. This was followed by a dinner, often of the big fish he had caught. He purposely kept very well-hydrated before bunk time so that he would have a natural alarm clock to remind him to run his safety checks on all systems throughout the night. He adhered exactly to this routine every day.

The Heart

Months before their departure, Stowe unrolled his navigation chart of the Atlantic and painted a big heart in the middle of the ocean between Africa and South America. As he showed it to Soanya he vowed that he would proclaim his love for her by drawing an enormous GPS heart in the Atlantic and he placed the subtitle of “The Love Voyage” on their adventure. After rounding Cape Horn and returning to the Southern Atlantic he observed from his GPS tracking that it was time to revisit his GPS Heart of the Ocean. On day 751 (May 12, 2009) the heart was complete. He never made an announcement about the creation of the heart because he knew that the vagaries of weather could easily have ruined his ability to control his disabled schooner. “Then I did it,” he says, “and I was in deep ecstasy.” The satellite tracking system confirmed that he had drawn a perfect heart in the middle of the Southern Atlantic along the 20th parallel between Namibia and Brazil. The heart measured about 2,600 linear miles in circumference 1,200 miles across.

Months before their departure, Stowe unrolled his navigation chart of the Atlantic and painted a big heart in the middle of the ocean between Africa and South America. As he showed it to Soanya he vowed that he would proclaim his love for her by drawing an enormous GPS heart in the Atlantic and he placed the subtitle of “The Love Voyage” on their adventure. After rounding Cape Horn and returning to the Southern Atlantic he observed from his GPS tracking that it was time to revisit his GPS Heart of the Ocean. On day 751 (May 12, 2009) the heart was complete. He never made an announcement about the creation of the heart because he knew that the vagaries of weather could easily have ruined his ability to control his disabled schooner. “Then I did it,” he says, “and I was in deep ecstasy.” The satellite tracking system confirmed that he had drawn a perfect heart in the middle of the Southern Atlantic along the 20th parallel between Namibia and Brazil. The heart measured about 2,600 linear miles in circumference 1,200 miles across.

Today, the best-known practitioner of Performance Art is Marina Abramovic, who in 2010 compiled a total of 736 hours of silence while sitting still, opposite individual spectators, in the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art. After enduring eight hours a day between March 14th and May 31st critics hailed what was the biggest exhibition of performance art in the museum’s history. By comparison, at the same time Stowe was completing his Heart of the Ocean while racking up 27,648 hours on a voyage that was one massive performance piece.

The Masterpiece of Man on the Sea

A few weeks later Stowe began to draw the world’s largest GPS art. It would take nine months:

A few weeks later Stowe began to draw the world’s largest GPS art. It would take nine months:

“As I sailed up the southeast Trade Winds I was rocked by 31,000 waves a day. I knew I had already been rocked and set in violent motion far longer than any human body and I needed a break. With my unique knowledge of the ways of the seas, I needed to find a place of respite. That is how I found the exact place in the sea where I could abandon all sense of direction and surrender my will to control the sea and myself and let nature do with me what she would. I was swept here and there, but I refused to look at the compass or direction. This may be my greatest accomplishment, what no man has conceived or been able to do. In my mind’s eye while I viewed from high, I saw my track create a spontaneous abstract squiggle that I called, The Masterpiece of Man on the Sea. The reason this drawing is greater than my Turtle, Whale or Heart is because I had to abandon myself to the sea to make it. The sea actually made it. For the other drawings I had to impress my will upon the sea. That is what man had to do since the first men ventured onto the sea. Over the years as I prepared for the voyage and while I was at sea, I was in an expanded state of consciousness and I knew I was overcoming the fears of Man through the ages. Abandoning myself to the sea took it to another level, because the foundation of the drawing was the physical triumph of my seamanship skills of the success of the “1,000 Day Voyage.” Then I was able to surrender and abandon myself to the sea and let the sea create The Masterpiece of Man on the Sea.”At this point one may summarize Stowe’s spiritual evolution in the following passage:

The individual, through prolonged psychological disciplines, gives up completely all attachment to his personal limitations, idiosyncrasies, hopes and fears, no longer resists the self-annihilation that is prerequisite to rebirth in the realization of truth, and so becomes ripe, at last, for the great at-one-moment. His personal ambitions being totally dissolved, he no longer tries to live but willingly relaxes to whatever may come to pass in him; he becomes, that is to say, an anonymity. The Law lives in him with his unreserved consent.

— Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p.204

Return of the Hero

The two worlds, the divine and the human, can be pictured as distinct from each other — different as life and death, as day and night. The hero adventures out of the land we know into darkness; there accomplishes his adventure, or again is simply lost to us, imprisoned or in danger; and his return is described as a coming back out of that yonder zone.

— Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p.188

The 1,000-day mark arrived in January 2010, but Stowe decided to remain at sea longer. It was winter in the Northern Hemisphere, a season when he was well-aware that storms in the North Atlantic would make his approach home very difficult. On June 17th, after 152 more days at sea he finally guided Schooner Anne past the Statue of Liberty underneath arches of water sprayed from the FDNY’s fireboats. Just two weeks earlier Abramovic had completed her endurance event at MoMA. He continued up the Hudson River and finally docked before a large awaiting crowd. Upon reuniting with Soanya and for the first time held his two-year-old son, Darshen, he announced to the press that he re-named his voyage “The Love Voyage” in honor of Soanya and his supportive family. From CNN to The New York Times, the media lauded the longest ocean journey, and he was featured in Ripley’s Believe it Or Not. Curiously, but perhaps fittingly, the Ripley’s illustrator featured a meteor next to Stowe’s portrait, not a schooner on high seas. After all, Stowe also broke the record for the longest solo voyage in space — doubling the 437 days set by the Russian cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov aboard the Mir space station. “I did what no man had ever done,” he declared. “I’m certain that nobody could do what I did. When they are capable of going 200 or 300 days non-stop without resupply, then I’ll say they might have a chance to aspire to my 1,152 days.”

The Schooner Anne’s last major ocean voyage was a repair trip to Guiana in 2011 with Soanya and Darshen aboard. The ocean will inevitably call again. In the meantime, we can appreciate in Stowe’s body of work an extraordinary approach that pushes our concepts about the genesis of creativity. His paintings are testament to how art may be generated from the unconscious dimensions of the psyche while at the same time their creator’s three-year passage required immersion and the fullest alertness in an environment both unforgiving and sublime.

— Peter Hastings Falk, 2018

Footnotes

References

The Sacred and the Oceanic

-

DETAILS

DETAILSBlown Out, Hand-Stitched Rum Smuggler Sail on Green, 2018

53 x 41 inches (134.62 x 104.14 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlue Sails, 2017

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPrimitive Bird Optical Altar, 2018

87 x 53 inches (220.98 x 134.62 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSBlown Out, Hand-Stitched Rum Smuggler Sail on Green, 2018

53 x 41 inches (134.62 x 104.14 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlue Sails, 2017

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPrimitive Bird Optical Altar, 2018

87 x 53 inches (220.98 x 134.62 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

No Events Found.