Born in Baghdad in 1953, Qasim Sabti became crippled as a seven-month-old baby. Because he grew up in a neighborhood with many athletes who were local heroes, he instead earned attention by distinguishing himself with his artistic abilities. As a teenager, students would pay him a falafel sandwich for a drawing or for one of his poems or love letters in beautiful Arabic calligraphy.

Upon graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad he established a workshop for Arabic calligraphy and painting. Beginning in 1985, he taught at the Baghdad University of Technology, and in 1986 participated in the first Baghdad International Biennial. In 1987, he returned to the Academy of Fine Arts to teach painting.

In 1992, Sabti founded the Hewar Art Gallery in Baghdad, which has since become an important and active oasis for Iraqi artists (“Hewar” means dialogue). He faced many obstacles in starting a gallery in the midst of the embargo because the government stopped subsidizing any art-related projects except portraits of Saddam Hussein. And, because Sabti was not allowed to travel to sell his art abroad, he had to reply upon the diplomats, journalists, and employees of the United Nations and the Red Cross who visited his gallery.]

Steve Mumford, a New York-based artist who was embedded with the coalition troops during several extended tours, described Sabti in 2003 as “a charismatic, handsome man in his 50s, who holds court most mornings in the gallery and the garden in the back, where there is a charming café, surrounded by lush plants and sheltered from the sun by a corrugated tin roof supported by antique columns. It’s the greenest place I’ve seen in Iraq, and on this particular October morning it’s buzzing with energy, with groups of men and a few women talking animatedly.” Mumford, who has received critical recognition for his watercolors documenting scenes in Baghdad, says that “Artists of Qasim’s generation were the students of the ‘Pioneers,’ the first generation of Iraqi artists to bring modernism to Iraq, often inspired by their studies not in Europe but in Turkey. Indeed, modernist abstraction influenced by European and American schools is the reigning painting style in Baghdad.”

Currently, Sabti serves as Vice-President of Iraqi Plastic Artists Society, which has 1,780 members. He is also Secretary of the Iraqi Cultural Council. His paintings are in private collections throughout Europe, the Middle East, the United States, Japan, and Korea.

Collage: The Iraqi Phoenix

-

DETAILS

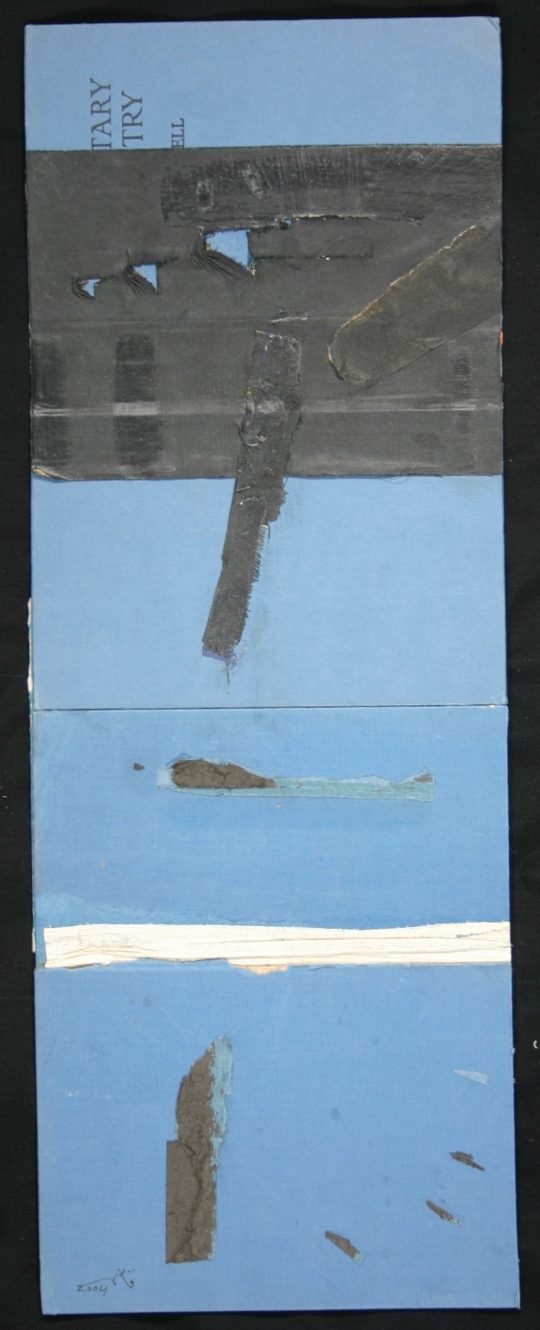

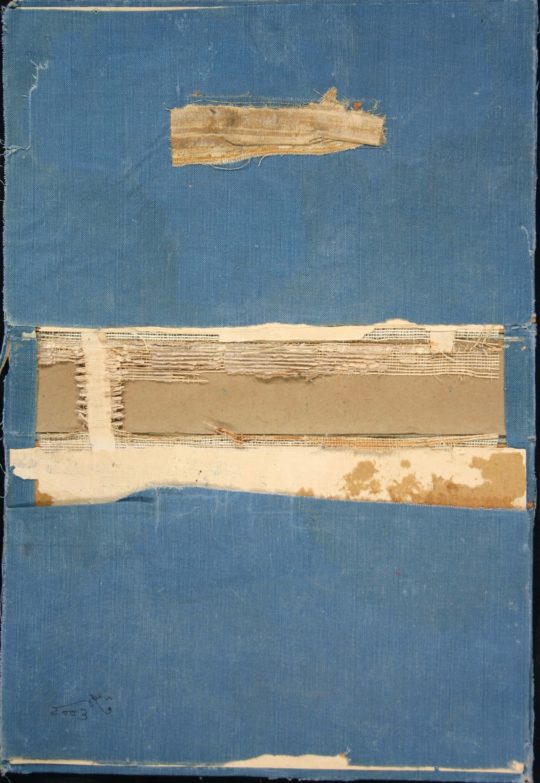

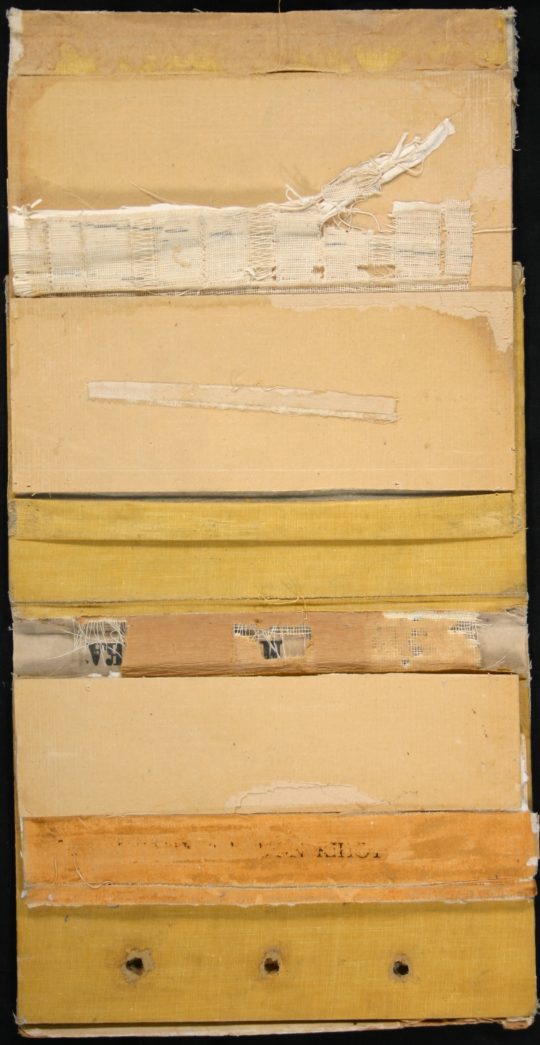

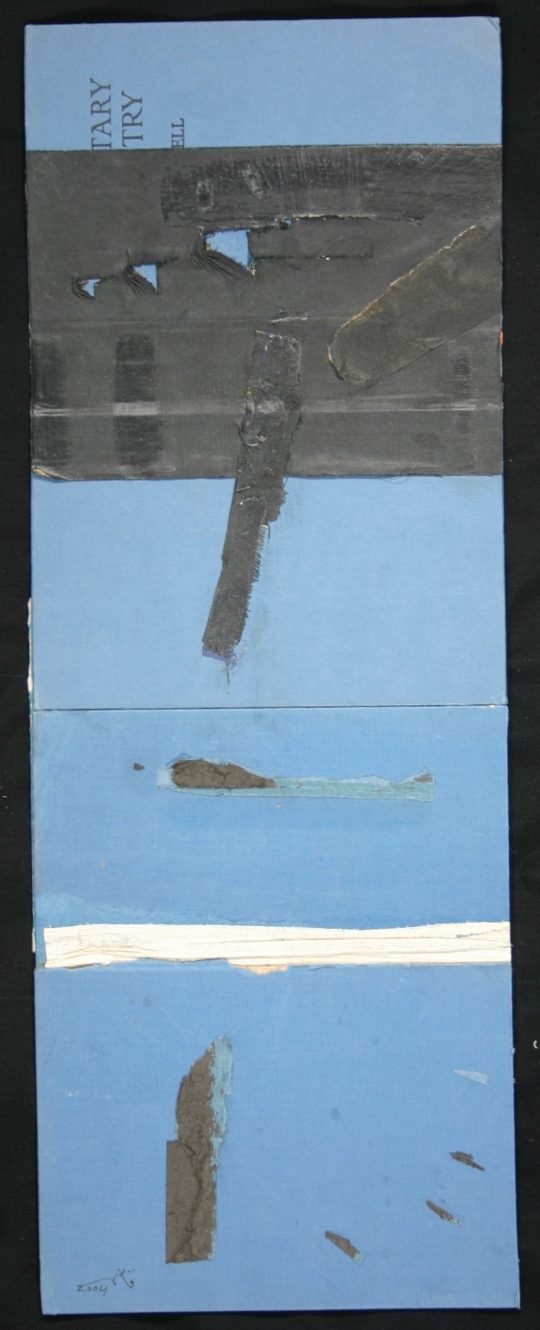

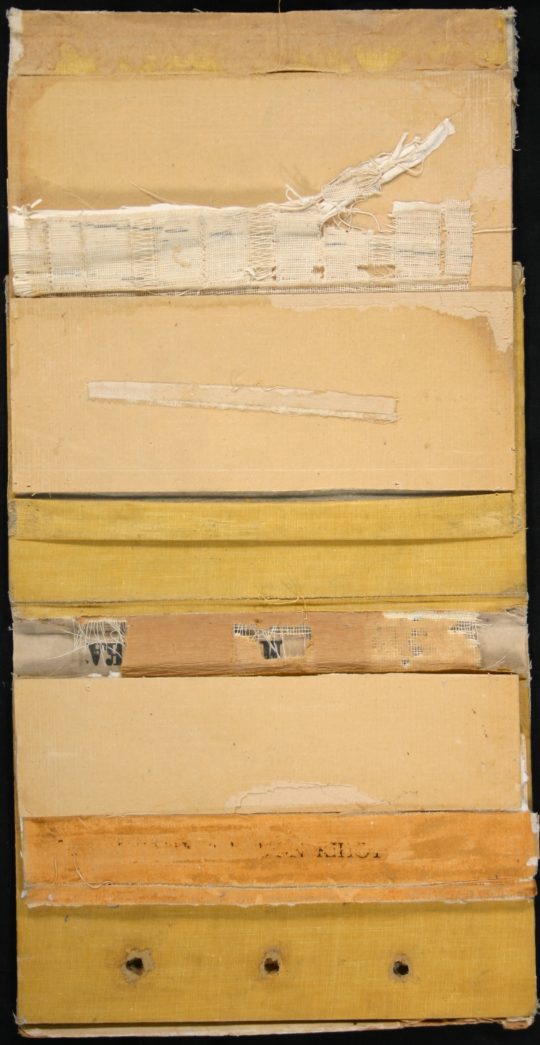

DETAILSUntitled No.1, 2004

7.75 x 20.5 inches (19.69 x 52.07 cm) -

DETAILS

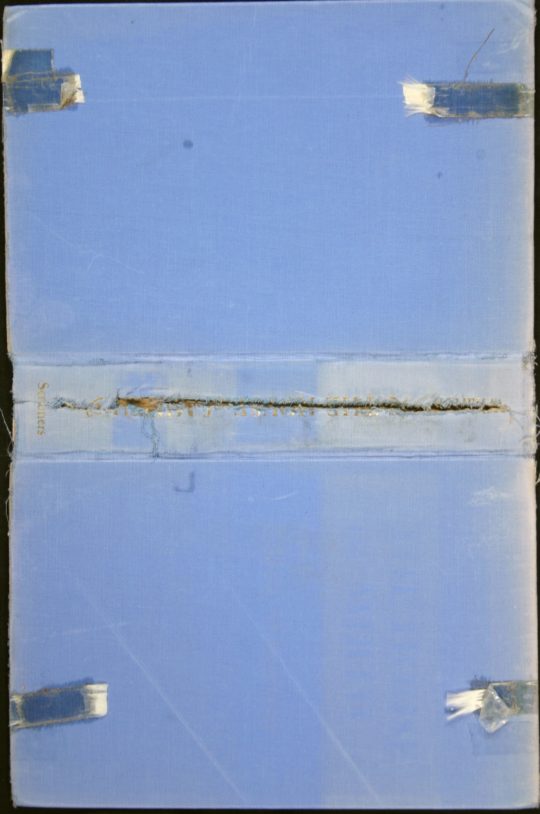

DETAILSUntitled No.16, 2005

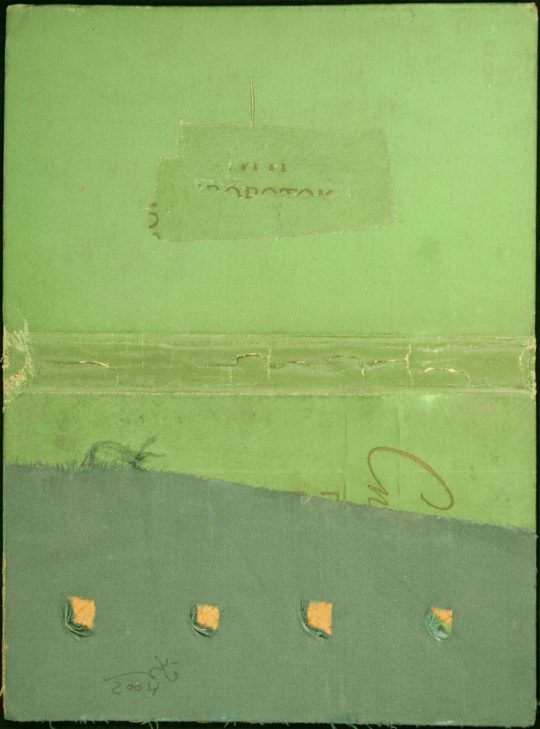

9 x 14.5 inches (22.86 x 36.83 cm) -

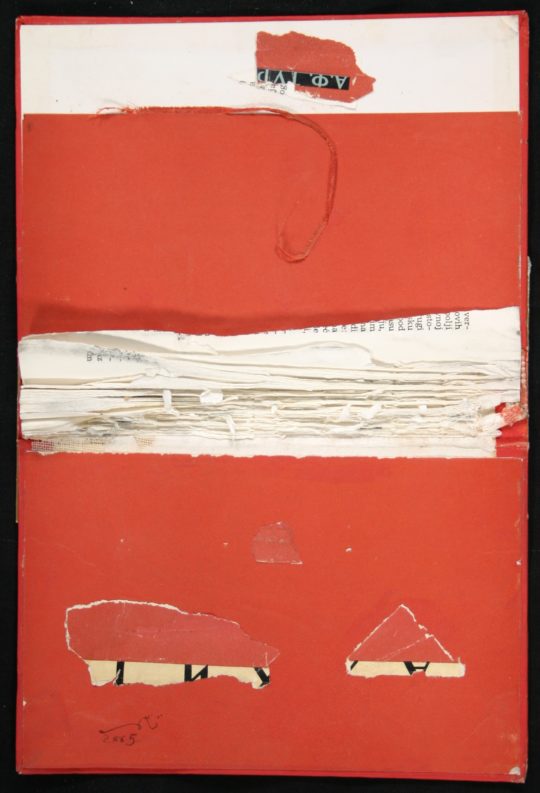

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.18, 2004

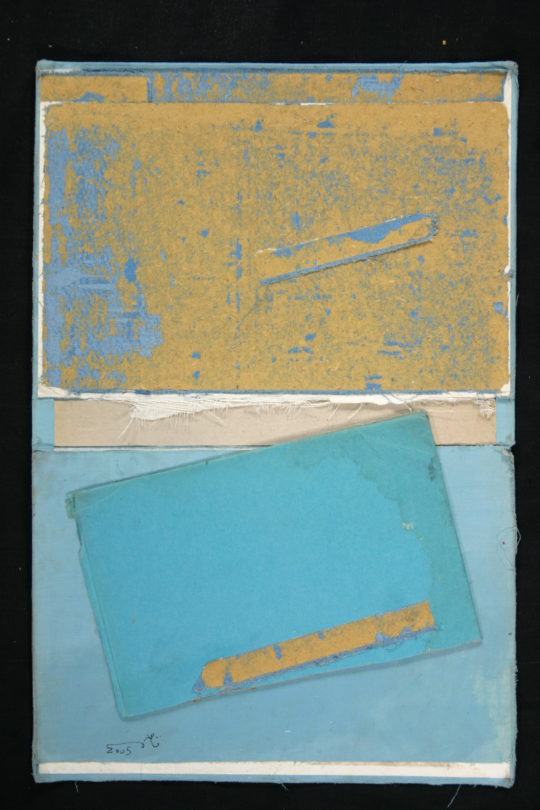

9 x 15.25 inches (22.86 x 38.74 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.2, 2005

8 x 18.5 inches (20.32 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.3, 2005

9 x 18.5 inches (22.86 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

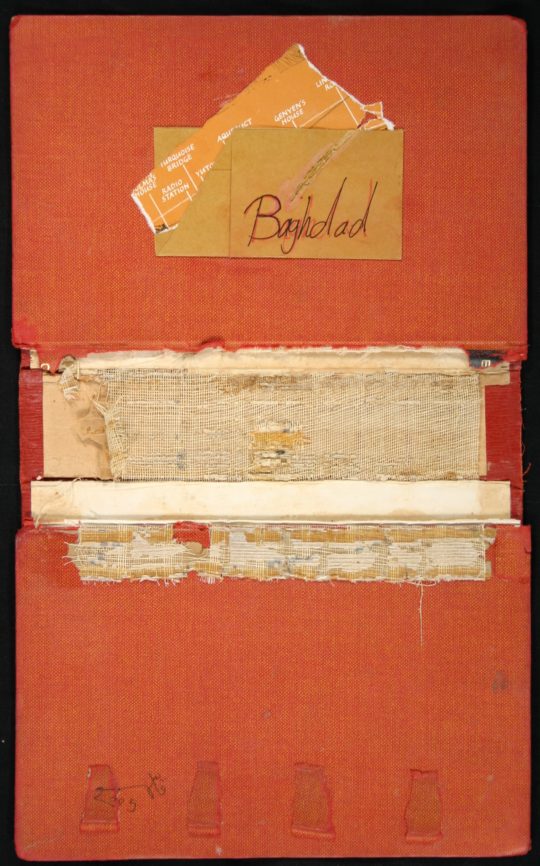

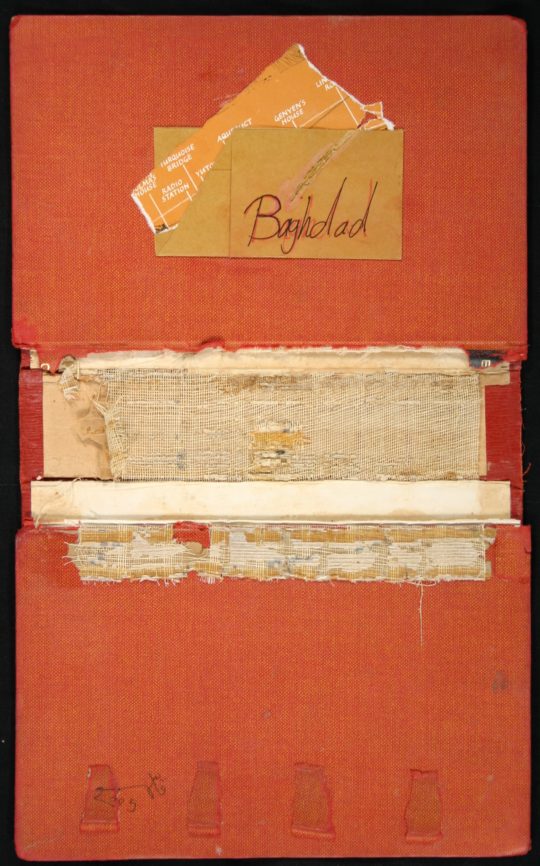

DETAILSUntitled No.30, 2003

9 x 12.5 inches (22.86 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

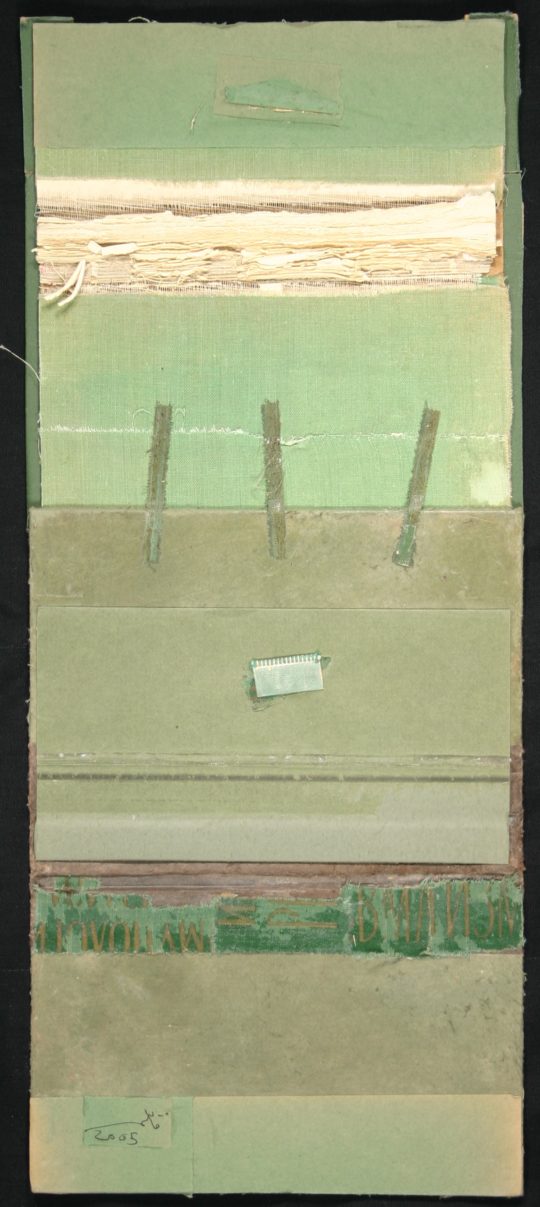

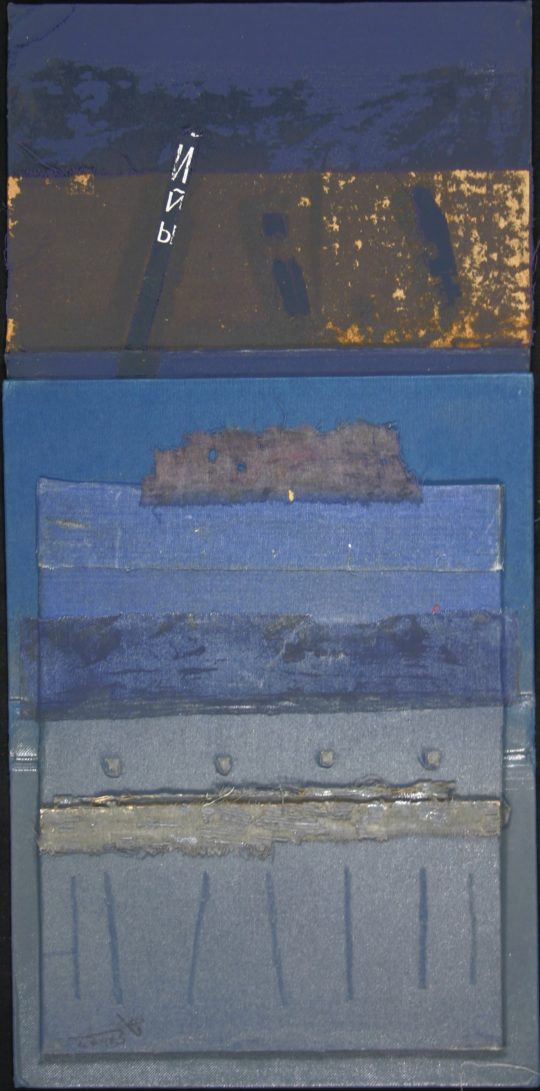

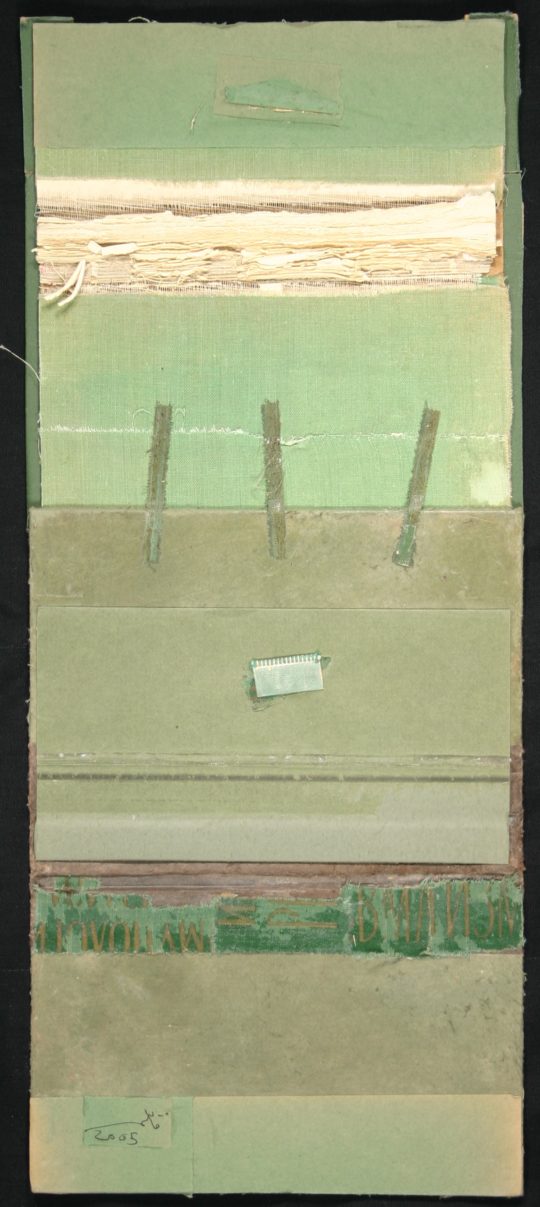

DETAILSUntitled No.32, 2005

9 x 21.5 inches (22.86 x 54.61 cm) -

DETAILS

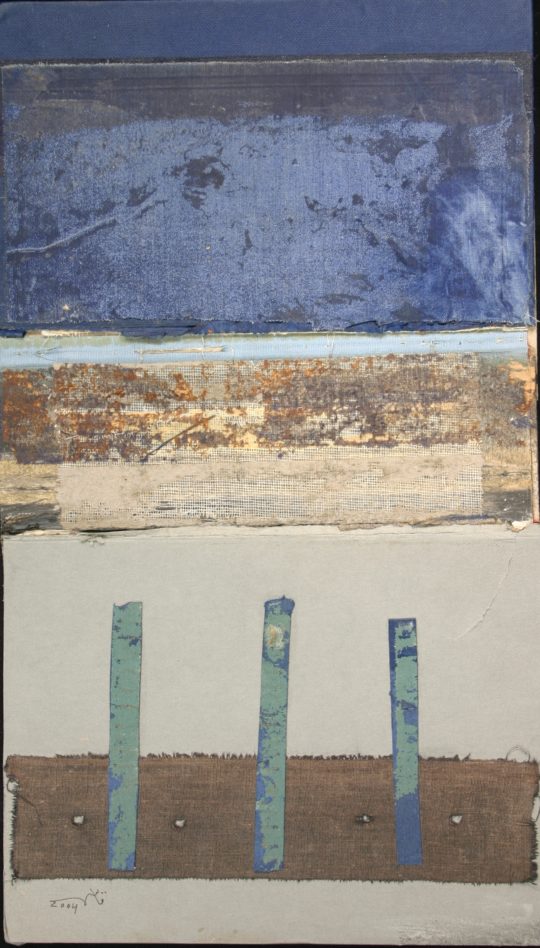

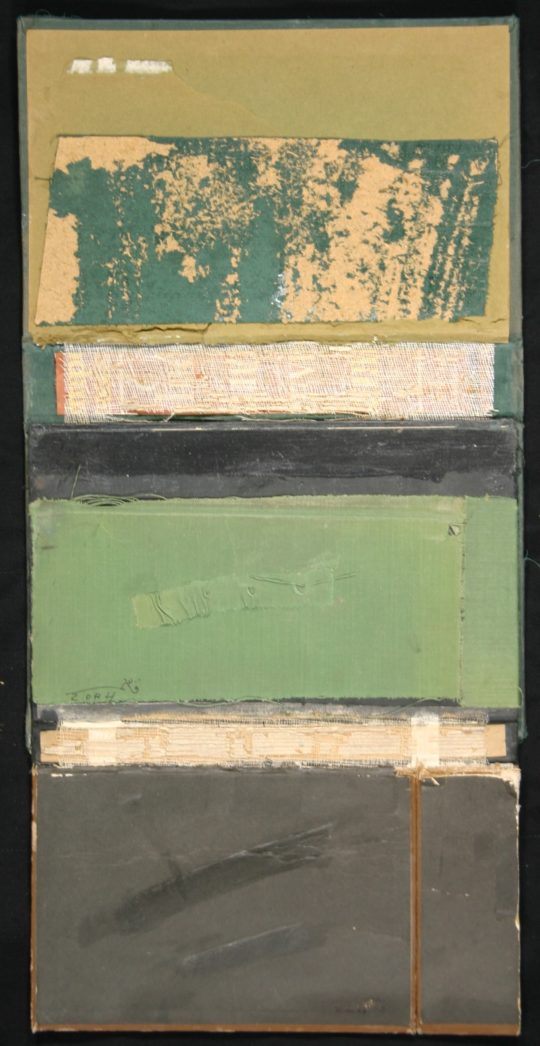

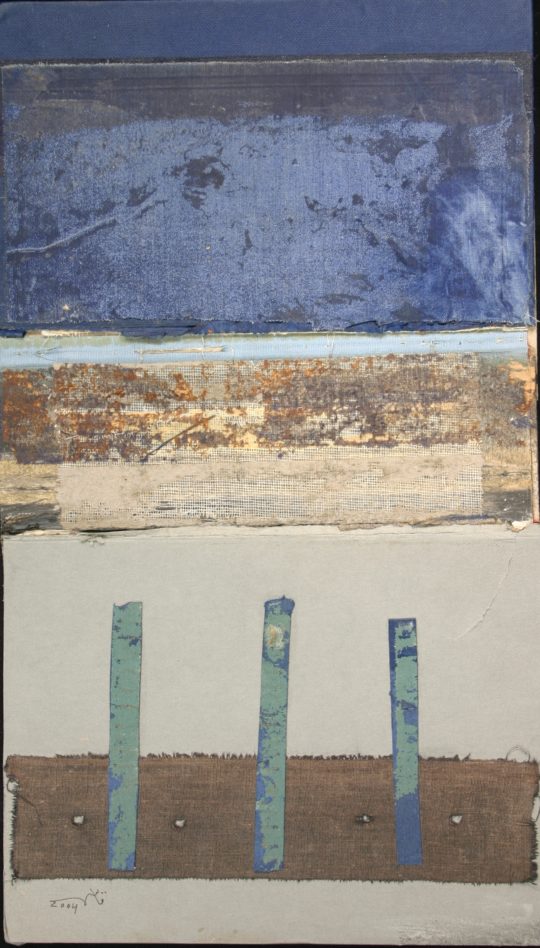

DETAILSUntitled No.33, 2004

9 x 18.5 inches (22.86 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.35, 2003

9 x 19 inches (22.86 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.39, 2004

8 x 11 inches (20.32 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.4, 2004

9 x 18.5 inches (22.86 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.43, 2003

8 x 16.5 inches (20.32 x 41.91 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.48, 2003

8 x 12.5 inches (20.32 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.6, 2005

8 x 12 inches (20.32 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.60, 2005

9.5 x 14.5 inches (24.13 x 36.83 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.65, 2003

10.25 x 16.75 inches (26.04 x 42.55 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.1, 2004

7.75 x 20.5 inches (19.69 x 52.07 cm) -

DETAILS

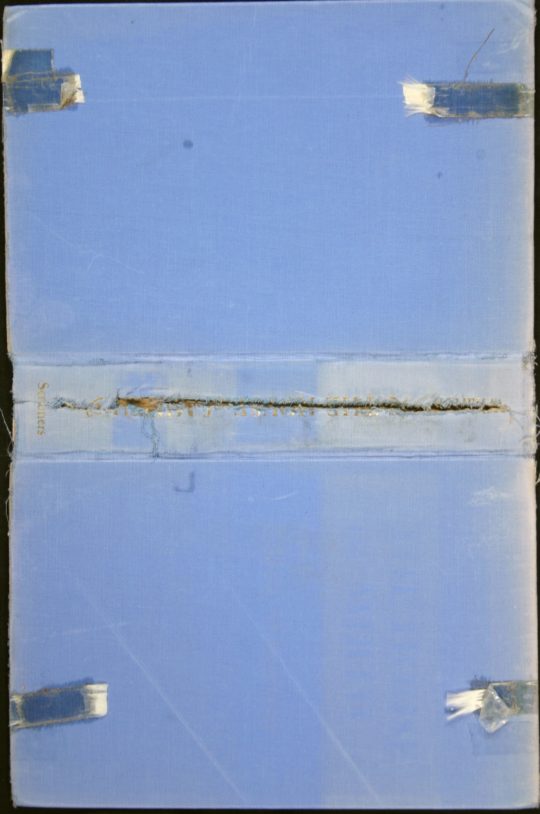

DETAILSUntitled No.16, 2005

9 x 14.5 inches (22.86 x 36.83 cm) -

DETAILS

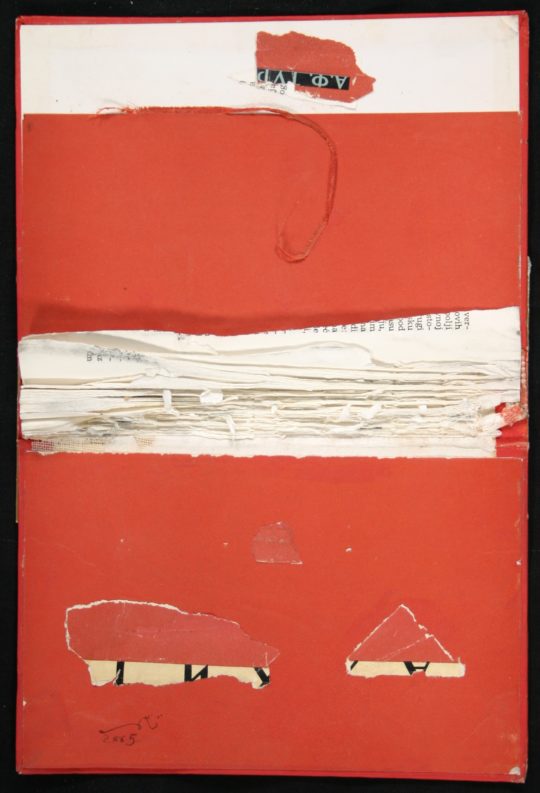

DETAILSUntitled No.18, 2004

9 x 15.25 inches (22.86 x 38.74 cm) -

DETAILS

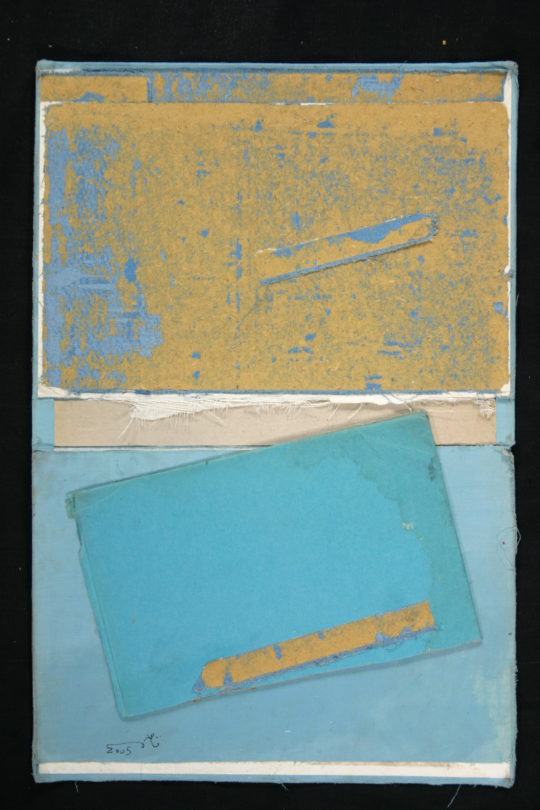

DETAILSUntitled No.2, 2005

8 x 18.5 inches (20.32 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.3, 2005

9 x 18.5 inches (22.86 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.30, 2003

9 x 12.5 inches (22.86 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.32, 2005

9 x 21.5 inches (22.86 x 54.61 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.33, 2004

9 x 18.5 inches (22.86 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.35, 2003

9 x 19 inches (22.86 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.39, 2004

8 x 11 inches (20.32 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.4, 2004

9 x 18.5 inches (22.86 x 46.99 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.43, 2003

8 x 16.5 inches (20.32 x 41.91 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.48, 2003

8 x 12.5 inches (20.32 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.6, 2005

8 x 12 inches (20.32 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.60, 2005

9.5 x 14.5 inches (24.13 x 36.83 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.65, 2003

10.25 x 16.75 inches (26.04 x 42.55 cm)

A Tale of the Phoenix

This is the story behind the collages, as told by the artist:

“In April, 2003, the bombings took a heavy toll on Baghdad. Many parts of the city were reduced to rubble. Worse, chaos broke out in the streets, driving the city into utter hell.

The morning after that first sleepless night I went to check on a place most dear to me, the Academy of Fine Arts. It was here that I had studied and enhanced my artistic skills. And it was here that I have taught painting to many students. To my dismay, the Academy’s street was littered with books, and pages torn from them blew in the dry wind. As I entered the Academy’s library, my senses were abruptly confronted by an acrid smoke that silently drifted above irregular mounds of charred books. In that instant of discovery, combined with pain, I saw that my beloved Academy had become another victim of a mob out of control. They had emptied the library shelves and set the books afire. The destruction was total. As I walked about, the pressure of my feet on damp and partially burned pages seemed to gently squeeze more pungent odors into the silence around me. I realized that a new bitterness in the air was the source of my tears. I just couldn’t be certain how much of those tears were caused by the smoke and how much were from being emotionally distraught.

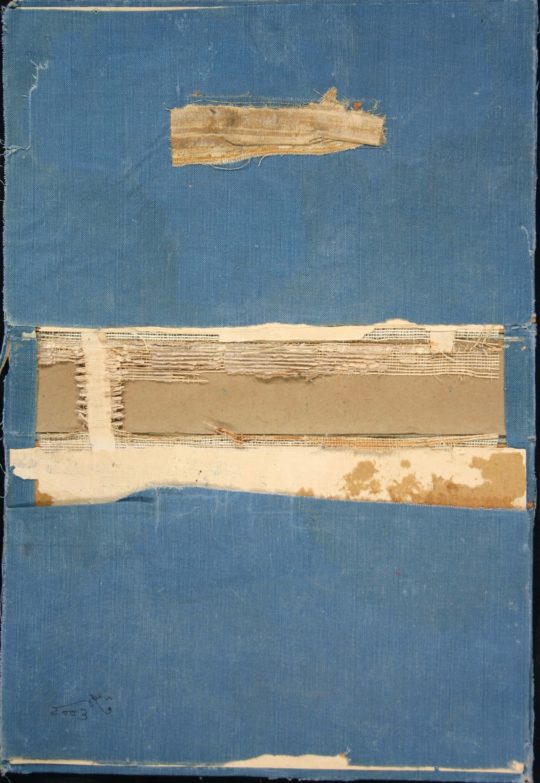

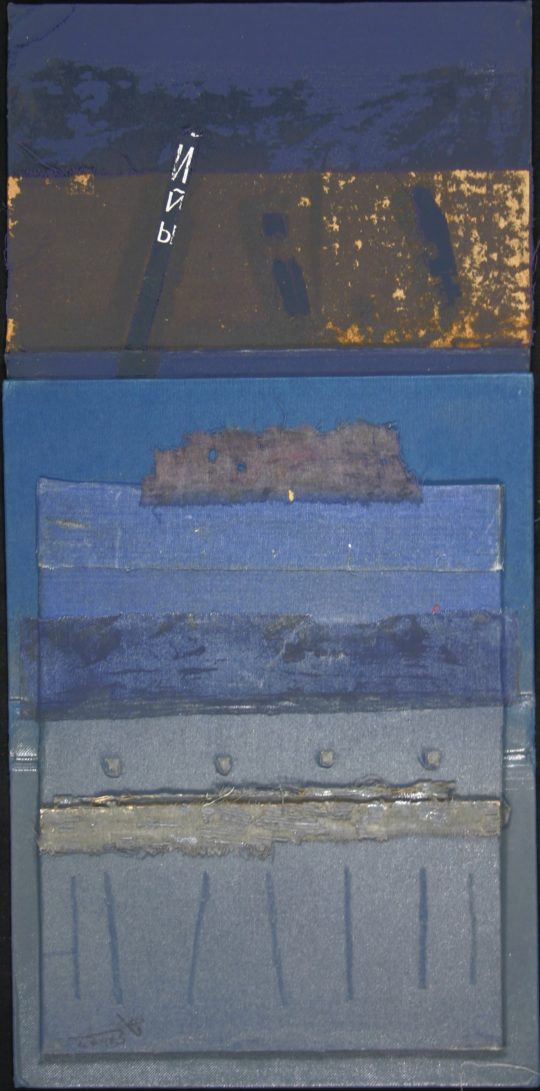

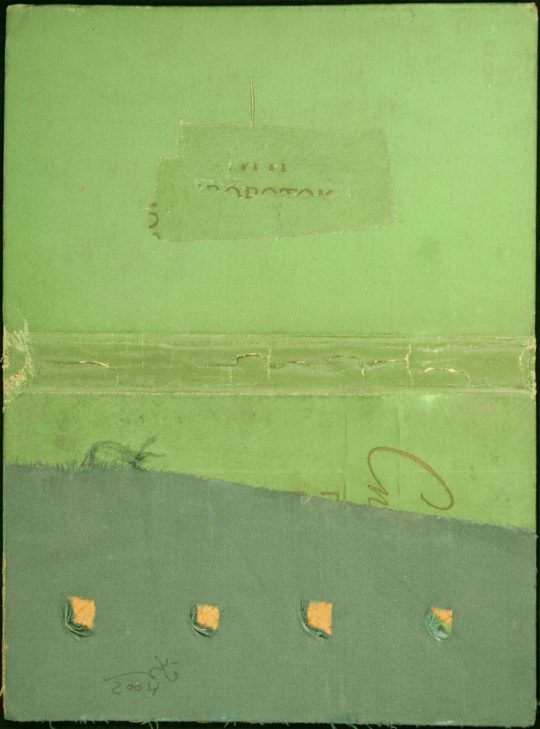

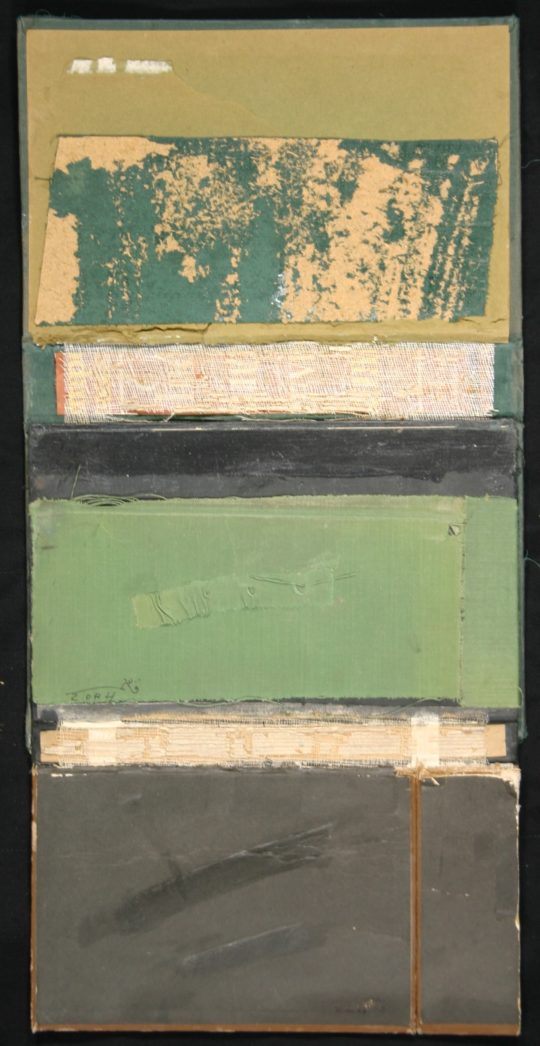

I felt like a fireman desperately in need of finding survivors. As I pushed through the piles, I noticed a few books that, although covered with soot, appeared to have survived. That’s when I spotted a book with a pale yellow cover. As I picked it up, I felt my fingers shaking. I brushed off the soot. Here was a survey of beautiful Russian landscape paintings. Suddenly, just as I started to turn the pages, the book collapsed. The whole block of pages, first weakened by the fire and later by the water, dropped from its spine. The pages scattered around me on the damp dirty floor.

Now I held only the cloth cover. Looking closer, I was haunted by the little details of life that filled the inside cover: strips of cotton, some Arabic verses scribbled in pencil, notes written by the librarian. My imagination was reborn. Here I found the essence of life deeply inscribed as signs of one book’s extensive journey. I was filled with a new sense of life and hope. I also found it visually inspiring. Like the fireman realizing that some victims were still breathing, I began to gather together more covers that called to me. The appearance of the cover was most important. Collectively, these books challenged me to bring them back to life from their graveyard floor.

I brought a pile of the damaged covers back to my studio and immediately started to work. With passionate fingers, I started to transform them. First, I rubbed their surfaces to remove much of their previous literary appearance. Next, I cut swatches from the covers, punched holes, re-applied loose delicate strings and lacey webbings, and even painted on them. In the process, I was ever-mindful that these books once documented so many great achievements in world history. Once, they had been valuable resources for the people of Iraq. Now, in their transformed state, these collages were bringing back life to books whose texts had been completely destroyed. These works of art are newly-derived from sacred bones. As such, they should stand as symbolic documents of the resilience of cultural life. They are also my attempt to gain victory over the destruction surrounding us in Baghdad.”

No News found.

No Events Found.