Coraggio — Linchpin of the 1980s New York Street Art Scene

by Anthony Haden-Guest

“Makers” is what the creators of images tended to be called in past times, not artists, and that’s a good word for Linus Coraggio, who is as compulsive a maker as I have ever watched. Or failed to watch, such as when I found that the laptop Mac, I had left on his worktable had been graffitied to within an inch of its useful life. The result of Coraggio’s thingmaking has been a huge and varied output of paintings, woodcuts, and design objects — such as chairs and neon lighting — but his central project has always been sculptures, some abstract, some incorporating figurative elements, and a very few wholly figurative but almost all made by welding used metals he found on the streets, in abandoned lots, or simply appropriated.

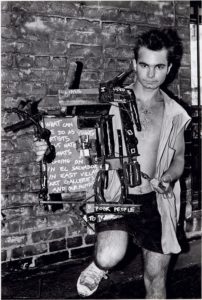

The work has made Coraggio both a fixture on New York Street art scene for forty years and part of the history of the form, being the inventor of 3D graffiti, a linchpin in the Rivington School (the artist collective on the Lower East Side), and ringmaster of the Gas Station, the gallery/clubhouse/performance arena on Second Street and Avenue B. In February 2022, a show of work by New York and Los Angeles street artists at Phillips on East 56th Street — “1970s Graffiti Today” — was curated by Arnold Lehman, long-time capo of the Brooklyn Museum, gave prominent space to Coraggio’s work. “Originally we were going to scatter them by date within the context of the exhibition,” Lehman says. “But we thought they would look better together. Like a streetscape.”

The powerful presentation raises a question. Basquiat and Haring, both in this show, have well-defined positions in the art world story. As do others here — such as Lee Quinones, Al Diaz, and Fab 5 Freddy — but Coraggio, who has been showing strong work for many years in galleries, museums, and public situations, nonetheless remains an elusive presence in the art culture. Just why? Disclosure: I rent studio space from Linus Coraggio. Which, I think, puts me in a good place to focus on this.

In Coraggio’s telling, the story jumps, strip cartoon-like, from scene to scene, beginning when he was six. His father, Henry Brant, an avant-garde composer, had taken the family from their home in up-state New York to Los Angeles while he was working on a movie soundtrack. One day, they walked to Watts Towers, the Art Brut knock-out put together between 1921 and 1954 by an immigrant Italian construction worker, Simon Rodia. “It was a sunny day,” Coraggio says. “People were moving in front of my line of sight. But as we got closer it became more amazing as the detail and the structure came into focus.” That juvenile experience was formative. So was the summer he spent five years later gluing toothpicks into a hollow triangle [he later refers to its “volume” so was it a pyramid?]. “I invented it as I went along,” he says. “I didn’t know how tall it would be, what the volume would be. I just went with the flow.” The first attempt didn’t work because he’d left the toothpicks the same length and the structure was askew. So, he pared down the toothpicks while building a second. “I nailed it perfectly,” he says. “It was totally geometric. About two foot four inches.”

He asked his mother, Patricia, what he had just made.

“Sculpture,” she said.

Okay, he was a sculptor. He wrote a sign: TOOTHPICK SCULPTURE. OVER THREE THOUSAND TOOTHPICKS USED.

Coraggio went to the High School of Music and Art and from there to college at SUNY Purchase. Self-described as an “odd kid,” he was unhappy with the offered digs. “1980 was a banner year for attendance so they had 3 or 4 people in rooms that were meant to be only for one. It was like Riker’s.” So, he set up an independant sculpture program for himself, with the building of a yurt to inhabit in the woods as a core part of it. As an add to his program he hauled his toothpick sculpture there and was filmed setting it aflame during a video class conducted by Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth.

Yes, a performance. Coraggio had been increasingly paying attention to artists who made work IR [?], like the Swiss Dadaist, Jean Tinguely, whose 1960 piece, Homage to New York, was an assemblage, which tore itself apart, flames flickering and wheels turning, in front of a MoMA audience. “Art wasn’t just making paintings that could be hung in a gallery,” Coraggio says. “There were actions. And things that could be done publicly. On the spur of the moment or planned, and that was something I wanted to try.”

There was another thing he wanted to try: Welding. Patricia, his mother, was a photographer, member of a group that documented industrial archaeology, and she would take him on drives to abandoned factories. He would focus on chunks of used metal. “I would pick them up and take them home,” he says. He also watched his mother arc-welding at Cooper Union. “I saw the power of doing that… the two pieces of metal smoking and cooling down from red hot to orange hot to colorless. It stayed in my mind, and I always wanted to try it.”

Students at Purchase couldn’t take welding until their second year, but an upperclassman showed him the process while he was a freshman. “Seeing the two pieces meld in front of your eyes is just captivating,” he said. “Chemistry in action.” He learned the character of metals. “Regular steel is primitive, coarse,” he says. “Stainless steel has a kind of easiness. Aluminum is soft, like cottage cheese.” Soon he was welding junked metal into conglomerate forms.

Coraggio was making moves in New York while still at Purchase, for instance, putting together a show at the activist art center, ABC No Rio. But the artworld of the Neo-Expressionists, with avid collectors and Art Star profiles in glossy magazines, although itself a recent growth, was not seen on the Lower East Side as opening doors but closing them. “The perception of SoHo to a young artist in the early 80s was one of exclusivity and commercial co-opting. It seemed that as a young artist you were frozen out from participating in the commercial art scene from the get-go,” Coraggio says. “As a young artist in the 80s there seemed no way for me to show artwork. And that felt claustrophobic.”

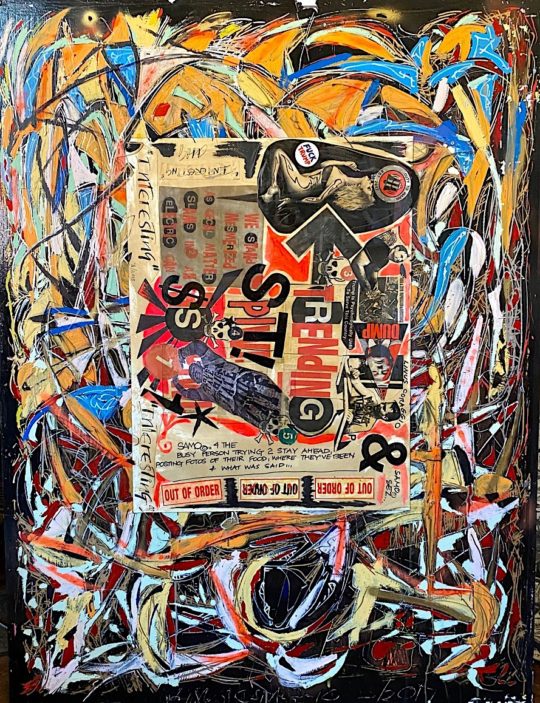

This led Coraggio to join the Street art movement during his second year at Purchase and he brought to it something new, his own practice of assemblage, by welding used metal throwaways to such convenient supports as “No Parking” signs. Like his predecessors in graffiti, he would often make words an integral part of a piece but where texts by, say, Basquiat and Al Diaz of SAMO, might involve cryptic references and/or touches of twisted poetry — A PIN DROPS LIKE A PUNGENT ODOR [why all caps? Should simply be in quotes] — Coraggio’s texts — I’M NO GALLERY WHORE — would be blunt. He called the new genre 3-D Graffiti.

Coraggio came up with a name for a collective of artists who shared his loathing for the on-going gentrification [and its galleries?], “The Rivington School,” and was instrumental in setting up their Sculpture Garden in a lot at Rivington and Forsyth. “I thought of Watts Towers when I first saw it” he says. It shortly became a junk wonderland. It was Ken Hiratsuka, a fellow street [Street does not need a cap, dos it?] artist, who told him of another potential site, an abandoned gas station on the corner of 2nd Street and Avenue B. Hiratsuka cuts his work into stone. Like sidewalks. Indeed, the two first met when Coraggio, skateboarding along a stretch of Spring Street he thought he knew intimately, jarred to a halt with a wheel caught in a new Hiratsuka cut. They were soon sharing a show at the club, Kamikaze. A Village Voice writer observed in 1987 that “Club 57, Danceteria, Kamikaze, and 8BC all specialized in art shows in the discotheque setting, but the concept was such a poor draw that they all closed.” The Gas Station, as Coraggio called the 2nd Street and Avenue B space when he opened it in 1986, would be more durable.

The Gas Station had several functions. As an art gallery, it was called Space 2B and had a DIY vibe. “People brought in their own art,” Coraggio says. “They put up room divisions and lighting and hung their own work.” As a night club it was the bailiwick of Paul Miller a.k.a. DJ Spooky. “There were different areas for different types of music,” Coraggio says. “The Rave scene and the Alternative Party scene-slash-Art Parties were probably the biggest. It was an ever-changing scene of different promoters, from Hardcore to Gay Disco. They would play until 4 or 5 in the morning.”

It was also a living space for Coraggio. DJ Spooky lived there for a while, and Richard Hambleton occupied a metal shed. It was also an arena for performances, not always with Coraggio’s blessing, as when GG Allin, a confrontational figure known for taking an occasional dump on-stage, showed up with his group, The Murder Junkies, in 1993. “There was looting, there was theft,” Coraggio says. Allin became bloodied as usual during what was his final performance, which is on You-Tube, and later that night he OD’d.

The gentrification of the nabe was unstoppable though. The Gas Station rent, $1,100 when Coraggio took it, was raised to $5,000 in early 1995. He didn’t pay for some months, while suing to prevent eviction. He lost. LA authorities had been narrowly prevented from pulling down Watts Towers, but the Gas Station was bulldozered in 1996. The space is now a condo. Of course.

Coraggio switched to making art full time, concentrating on sculpture. Some pieces are pure abstractions, and these can be hard-edged and Minimalist or more fluid, built from arcs and circles, and he would move from pure abstractions to pieces which reference figurative shapes or use found elements with figurative effect, as when a hammer head stands in for a human head. These include the many works which incorporate knives and choppers [do you mean meat cleavers?], usually [or “often with”] street-damaged Barbie dolls with threatening hi-tech instrumentation.

The Barbies are a series. Coraggio was increasingly working in series, as when he turned his attention to design objects in 1985 and began a series of usable chairs, using a Bus Stop No Standing sign to furnish one with its back, the rubber roll from a venerable typewriter on another, while the back of a third was made by welding a hammer to a sickle. This would the first of six distinct hammer and sickle chairs — one using two hammers. In 1986 Coraggio, himself a long-time biker, he made the first of a series of pieces that suggest a motorbike, frequently by cannibalizing bike parts. “That’s a windshield wiper motor,” he said of one, adding of another: “That’s the actual brake rotor from a Harley.”

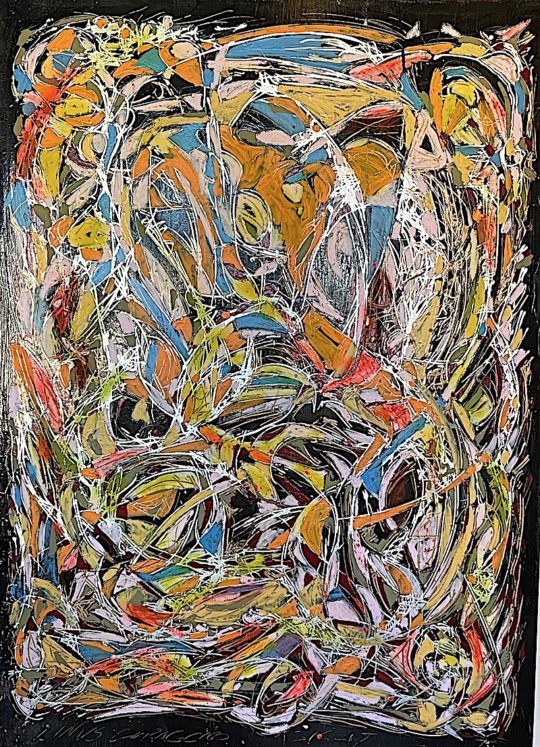

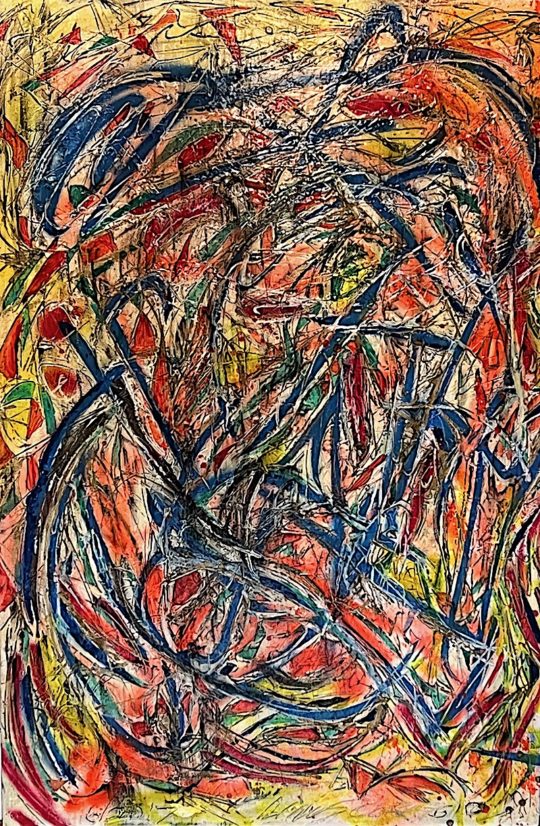

Coraggio has also continued to paint, mostly abstracted landscapes. He makes strong black and white woodcuts, which are figurative and involve text, and, of course, makes and installs 3D graffiti. Everything is clearly the work of Coraggio’s hand but his rejection of any notion of a signature style is unusual, to say the very least. The careers of artists, however unalike, have usually progressed in a similar fashion, which is that the artist beavers away until achieving a distinctive style which is successful, which he or she will develop longtime. An artist who drops such a successful MO for a radically different way of art-making is likely to run into headwinds — as with the reaction to Philip Guston’s 1970 show at the Marlborough Gallery, New York. Guston had had a long career as a well-regarded Abstract Expressionist but was now showing figurative canvases, with rawly cartoonish imagery, such as KKK hoods. Hilton Kramer headlined his New York Times review “A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum.” A Boston critic referenced Tom Wolfe to attack it as “radical chic.” Guston’s new work, for which he was congratulated by de Kooning, would soon be seen as crucial.

Coraggio didn’t just move on from one manner or artmaking to another though. He moved on from 3D graffiti into a plethora of directions. Nor was this an accident. “My father would work in different styles,” he says. “I thought that it was outrageous that anything was expected of an artist. Even in High School. Sitting in class and seeing one Kenneth Noland Target after another made my blood boil. It made an artist’s work boring and predictable.” I’ll move in a heavy gun here, Arthur Danto, the late philosopher, art critic of The Nation, who observed that there have been two art narratives since painting had developed from being an element in worship into being accepted as a distinct practice. The first had been Representation, Danto declared, and this, he specified, was born in 1400 and died with Monet. The second art narrative had been Modernism, which died for him in the early 60s. What that meant to Danto was that the forwards-moving momentum of the Isms was dead and done with. The current art world, he argued, had become an area where “nothing is ruled out,” where there are “no narratives” and “anything goes.” Linus Coraggio would, I think, go along with that.

Ackowledgements

Special thanks to Anthony Haden-Guest — a member of our Curatorial Board — for his insights into the life and works of Linus Coraggio, his friend and a leader of New York’s street art scene in the 1980s; and, to Noah Becker for kindly allowing this reprint of Guest’s text from the Feb. 2022 issue of Whitehot Magazine. The 1980s photographs from Coraggio’s collection are by Daniel Falgerho.

AbEx Graffiti

-

DETAILS

DETAILSAhgtastrophe, 2022

28 x 22 inches (71.12 x 55.88 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAnt Face, 2021

20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBad Subway (diptych), 2017

24 x 48 inches (60.96 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBK from NYC, 2009

30.5 x 37 inches (77.47 x 93.98 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlackdrop II, 2017

44.38 x 32.62 inches (112.73 x 82.85 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlackdrop III (a collaboration with Al Diaz and Anthony Haden-Guest), 2018

45.75 x 34.75 inches (116.21 x 88.27 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBrain Working, 2020

13 x 7 inches (33.02 x 17.78 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSColorfoghut Andes, 1999

21.12 x 15.25 inches (53.64 x 38.74 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSColorstacks, 2017

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSConey, 2019

46 x 56 inches (116.84 x 142.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCool Roseria, 2017

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFly Zone, 2017

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSJimipurplerain, 2016

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMag Match (diptych), 2016

30 x 60 inches (76.2 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMissing Half, 2016

24 x 20 inches (60.96 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNerve Fog, 2021

16 x 12 inches (40.64 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

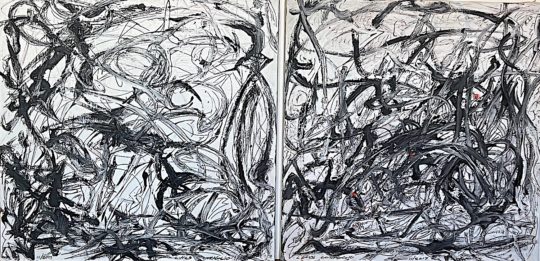

DETAILSNo B&W Show (diptych), 2017

18 x 36 inches (45.72 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOff-Center Year Knife, 2015

13 x 4.75 inches (33.02 x 12.07 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPark Pattern, 2016

36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPink Spring, 2011

19.25 x 27 inches (48.9 x 68.58 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPinstripe Intersections, 2017

54.25 x 69.75 inches (137.8 x 177.17 cm) -

DETAILS

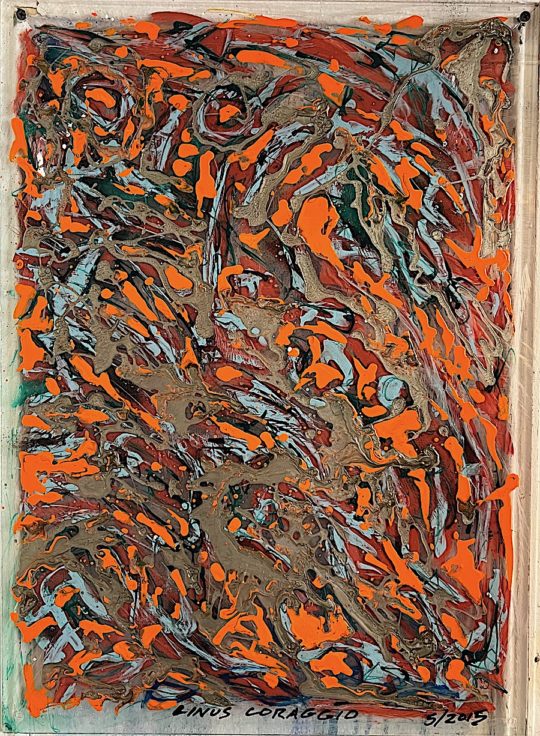

DETAILSPlexi Camouflage, 2015

23.5 x 17 inches (59.69 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPrecrasher, 2017

50.25 x 50.25 inches (127.64 x 127.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPuzzle Passion (diptych), 2017

30 x 48 inches (76.2 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSpandex Flags, 2017

63.5 x 67 inches (161.29 x 170.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSpatial Mosaic, 2022

40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

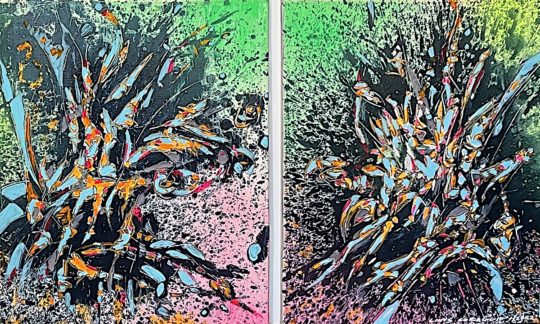

DETAILSStarry Cockfight (diptych), 2022

20 x 32 inches (50.8 x 81.28 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStreetsmart Slip, 2020

48 x 36 inches (121.92 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTall Curves (diptych), 2020

16 x 40 inches (40.64 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe 1-in-10, 2009

28.25 x 22.25 inches (71.76 x 56.52 cm) -

DETAILS

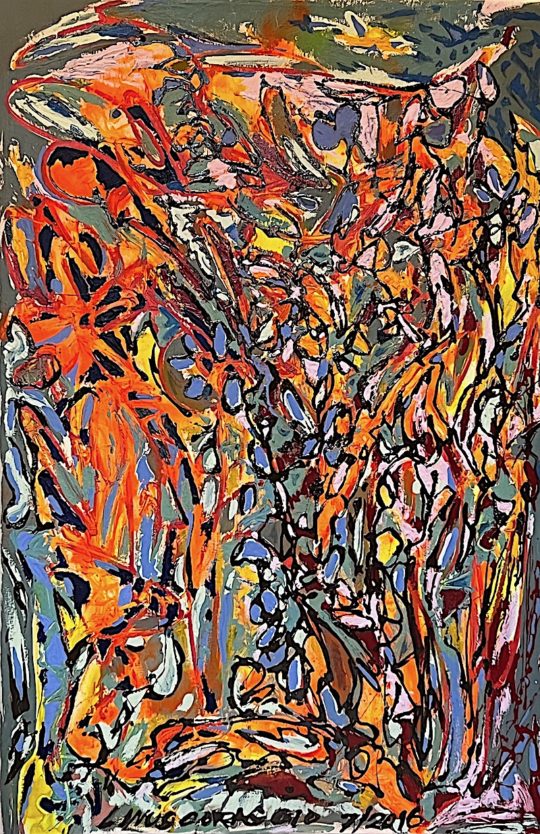

DETAILSThree Firenados, 2018

66.5 x 36 inches (168.91 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThree the Easy Way (diptych), 2017

20 x 32 inches (50.8 x 81.28 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTondo 1, from The New Planet Series, 2018

54 x 54 inches (137.16 x 137.16 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTondo 3, from The New Planet Series, 2018

38.25 x 38.25 inches (97.16 x 97.16 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTondo 5, from The New Planet Series, 2018

22.5 x 22.5 inches (57.15 x 57.15 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWhite Tower, 2014

14.75 x 6 inches (37.47 x 15.24 cm)