Master of the Midway

“I grew up in the circus and the rodeo during the Great Depression. You have to understand that this was a totally different world with totally different people.”

– Leo Jensen

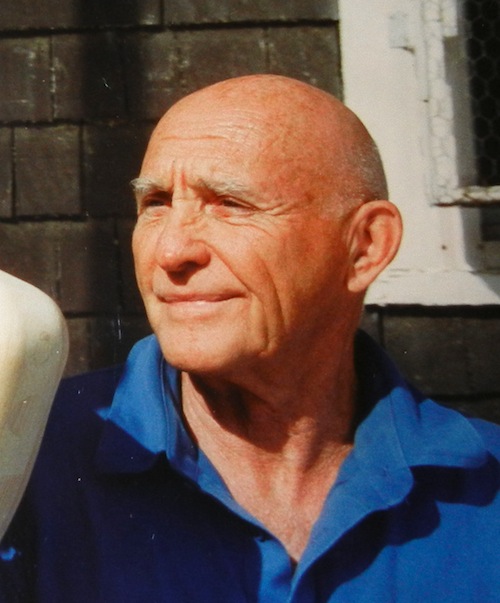

We are saddened by Leo’s passing on August 8, 2019. His sharp wit — ranging from playful to acerbic — emanated from every sculpture he created. The following essay shows that he was a pioneer in New York’s Pop Art movement and must be credited with inventing Kinetic Pop Art sculpture.

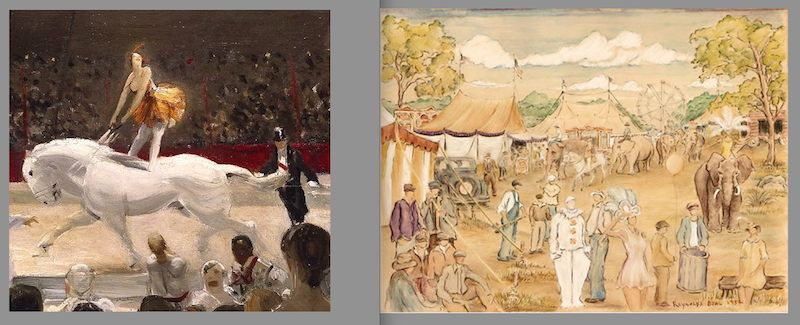

Since the late nineteenth century the list of American artists who have been attracted to the circus as subject matter is a long one. But a focus on the decade of the 1930s — the Great Depression — reveals a heightened interest. After all, during these surreal times most artists were still trying to figure out how to reconcile the prevailing more traditional Regionalist style with the maturation of modernism while the Surrealist movement was on a collision course with both. The circus provided a fantasy world into which both artists and the public could slip, fully immersed in exotic performances highlighted by brilliant colors, bizarre sights, and captivating music. Perhaps the most prolific were the brothers Reynolds and Gifford Beal who painted colorful plein air scenes of the circus ring and the Midway as well as scenes outside of the limelight. By tracing the titles of their paintings one could generate the itinerary of the circus over the decade as it crisscrossed throughout the Northeast. Walt Kuhn captured the characters of numerous circus clowns — most of whom appeared as if they could have been auditioning for a film noir. Alexander Calder spent six inspired years playfully crafting his famous toy Circus (now at the Whitney Museum) from a host of materials, including wire, wood, string, pipe cleaners, and bottle caps. Among the other American masters born before the end of the nineteenth century and drawn to the circus as subject matter during the 1930s were George Bellows, Yasui Kuniyoshi, Charles Demuth, and John Steuart Curry.

But this is not a story about yet another artist on that long list of mature modernists who during the 1930s delighted in observing and capturing the imagery of the circus. Rather, this is a story about a rara avis — an American artist who actually grew up in the circus — and it proved to be the catalyst of his creative vision. In order to fully appreciate how Leo Jensen developed his singular approach to Pop Art one must understand his life as a young circus performer as well as how at the same time he received his artistic training in this fantasy environment. The result is a fascinating and truly unique chapter in the history of American Art.

During the Great Depression the government provided many artists with jobs under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The result was thousands of murals in post offices and schools, sculpture in public places, and countless posters, paintings, prints, and photographs. For much of the decade, breadlines were fixtures on New York’s sidewalks while the extended period of drought turned the Great Plains so arid that it became known as the Dust Bowl. Farmers fled the plains seeking employment elsewhere. Most were drawn to California but often wound up in large camps of migrant workers. Photographers working for the Farm Security Administration captured some of the most poignant images. Iconic among them are Arthur Rothstein’s Dust Storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma and Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother.

Owing to this bleak environment, the public found several forms of diversion. Families typically gathered about the radio to hear shows together. Movies offered another form of escapism, especially in madcap comedies and gangster flicks. In 1935 the first comic books appeared, quickly winning enormous readership. But it’s the circus that stands out as America’s greatest entertainment industry. With its roots in Europe, the American circus took hold in the mid nineteenth century, presenting equestrian feats, dog and monkey shows, and elephants — all accompanied, of course, by the ubiquitous clowns, gymnasts, acrobats, and the flying trapeze.

By the early twentieth century the circus had evolved into an elaborately orchestrated series of events. Before arriving at the three-ring circus one would pass through the Midway, that vibrant central lane along which sideshows present a dazzling panoply of amusements, ranging from bearded ladies to sword swallowers, snake charmers, mermaids, and tattooed ladies. Each sideshow displays a great colorful banner to entice the public. Just the day before opening the Midway and the great circus tents are erected in an astonishing flurry.

The present story is firmly rooted in one circus that toured the Upper Midwest during the Great Depression. It was part of the extensive circus organization created by John Ringling, who in 1929 formed a virtual circus monopoly by acquiring all of the major shows, such as Sells-Floto, Al G. Barnes, and Hagenbeck-Wallace. In this Minnesota circus the character in charge of painting the colorful banners and fixing the wagons was “Ol’ Rip.” Despite his claim of lineage to an important Boston family, his circus family simply accepted him for what he was: a black sheep who was an artistically gifted “rummy.” Having worked in a shop creating carousels he brought great experience to the circus. But by early afternoon he was usually so drunk that he passed out at the spot of his last task. Unfortunately, that usually meant he collapsed in the Midway during the busiest — and most dangerous — times of setting up and taking down the circus. Countless workers rushed through the Midway kicking up dust as they guided horses hauling large wagons, steered elephants, hoisted tents, and erected sideshows.

After several incidents of waking up safely tucked under a parked wagon instead of under an elephant, “Ol’ Rip” began to inquire who had been so kind to drag him out of harm’s way. When he discovered it was nine-year old Leo Jensen — the boy who performed as a trick rider — he asked the circus promoter if Leo could be assigned to him as an artist apprentice.

That circus promoter was Albert Jensen, the boy’s father. Albert had grown up in Newell, Iowa to Danish immigrants but his education never passed the fourth grade. However, on his father’s horse farm he learned how to train “broomtails,” those wild horses captured by the cowboys. He also trained as a cabinet-maker and woodcarver. Both were skills he would later pass on to his three boys. During he early 1920s Albert married Lillian von Lunenberg and they settled in her small prairie farm town of Montevideo, Minnesota, 200 miles due north of Newell, Iowa. Lillian’s father, trained as a carpenter in Prussia, had sought his fortune in the Wild West and upon arrival joined the U.S. Army. In the summer of 1876 he was part of the 7th Cavalry that arrived too late to save Custer from the massacre at the Little Bighorn River in Montana.

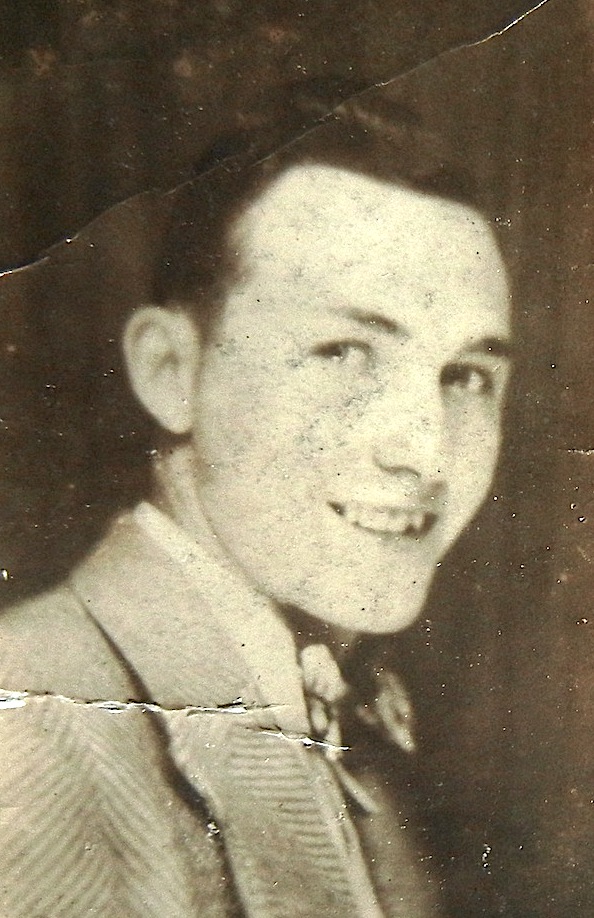

Leo Vernon Jensen, the middle of the three Jensen brothers, was born in 1926 in Montevideo. The town is located at the convergence of the Minnesota and Chippewa rivers. It boasted two or three telephones. The big city — Minneapolis — was approximately 140 miles east. When the Great Depression began to grind its long and relentless path through America it became painfully clear to Leo’s father that the demand for cabinet-making had disappeared. Albert quickly adapted and became a circus promoter. With horses deep in the family background it was natural that rodeo trick riding would be featured as an essential attraction under his circus management.

Traveling throughout the Upper Midwest, Albert produced three-ring circuses over shorter two- to three-night stands. The whole Jensen family became fully immersed in the circus. Lillian Jensen trained the performing dogs. Of her three boys, Pat was too young to help but her two older boys, Leo and Duke, had grown up with horses and they began trick riding. They were nimble, confidently hopping on and off and balancing precariously as the horses ran about the ring. These performances were the result of arduous training. For safety during training the boys wore a wide leather belt with loop in the back. Attached to that loop was a rope, which extended to a long boom. The boom would then swivel about a big pole at the center of the ring as the horse circled around and around the diameter. Of course, this safety mechanism was never used during the live performances and Leo incurred a number of injuries over the years.

Leo’s parents had also long recognized that their son was a precocious artist. “Empty cartons and containers and the abundant colorful debris of the circus and carnival life served the demands of my infant artistry,” he recalled. Encouraging his talents, Leo’s parents agreed that he could to take on a second job, that of artist apprentice to “Ol’ Rip.” For the next five years Leo became rooted in the art of the Midway. The circus wagons featured elaborate and deeply carved polychrome figures that were inset but would chip, crack, or become broken. He was taught how to repair them with wood filler and even carved replacements for missing pieces. He then repainted them in their bright colors. He also learned how to paint the big banners along the Midway that lured people to the “flat joints” — those attractions such as shooting galleries with their spinning target wheels, and ball swings to knock-down milk bottles.

“The glamour of the Midway and the fierce thrills of showtime were wonderful to me but more wonderful still was the fun of paints, brushes, and tools to carve a lion or a word. For I had grown a bit older and discovered Ol’ Rip, the alcoholic artist-handyman who traveled with us to mend and paint and gild the parade wagons, the Midway banners, and the carousel. All circus children must work or perform. Except for matinée days I went to resin-back class every morning with Ol’ Rip. In my free time I followed Ol’ Rip everywhere and he taught me the artist’s trade.”

Here was an artistic boy painting circus wagons and banners amidst clowns, acrobats, and elephants. He became absorbed by a daily palette of glittering colors, lively movement, arousing music, and distinctive smells. Indeed, the circus became the perfect environment for cultivating an artist who as he matured would draw deeply from a vein of popular culture where the mandate was to “amaze and delight” the audience — while being immersed in its own layers of surrealism.

“Ol’ Rip was found dead one day and though I mourned him sincerely I happily became his successor in the art of the circus wagon and banner. My precocious talents and joy in the trade were obvious and welcomed by all. Before the Great Depression my father was a cabinetmaker. Now he took over my instruction in carving and woodwork. How wonderful to discover in my own father skills far more developed than those I had so admired in Ol’ Rip!”

When Leo turned fourteen in 1940 he and his older brother Duke “retired” from the circus to join the rodeo. At the same time their parents realized their itinerant bronco riders needed an education and settled in Deep Haven near Minneapolis so that the boys could attend high school. The move not only gave them a greater sense of permanence and stability but also brought Leo within the sphere of the Walker Art Center (first public art gallery in the Upper Midwest established just thirteen years earlier) and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Ever energetic, Leo played football and was a state track champion. But as soon as the school year ended the boys set off to perform with the rodeo for the summer. They found their next great adventure in “Wild Bill Blomberg’s Wild West Show.” They traveled with the rodeo throughout the West, including stops in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Edmonton and Calgary, Canada; Portland and Pendelton, Oregon; and, Amarillo, Texas. When Jensen wasn’t performing he was haunting the art museums everywhere he went. While in the Pacific Northwest he was particularly drawn to the monumental totem poles and other painted wood carvings of the Haida and Tlingit tribes. “I did trick riding and rode a bronc from time to time,” says Jensen, “but being an artist was all I ever wanted to be. I spent my free time drawing and painting signs and banners.” Indeed, as the brothers worked the rodeo circuit Duke discovered a thriving business selling Leo’s animal drawings.

Jensen recalls with fondness the Clint Eastwood movie Bronco Billy (1980) as accurately depicting the life of the circus and rodeo. Eastwood’s portrayal of a run-down traveling circus star in “Bronco Billy’s Wild West Show” bears striking similarities with Jensen’s experiences in “Wild Bill Blomberg’s Wild West Show.”

Focusing on Art… Off to New York

“I don’t distinguish between fine art and circus art.

The only question is whether it’s good or bad.”

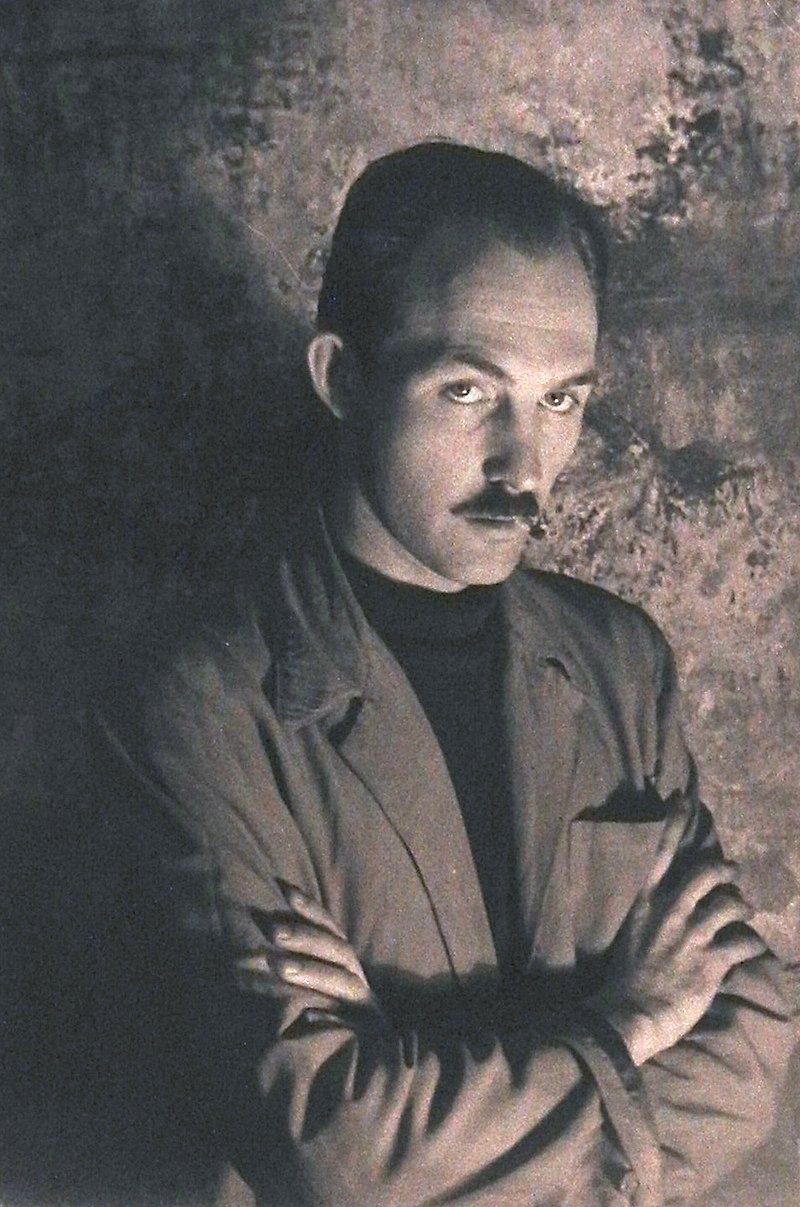

Word War II was still raging when Jensen graduated from high school. He tried to enlist in the U.S. Navy but was rejected owing to the string of injuries he had incurred from riding broncos, including a broken eardrum and a hernia. But he had won a scholarship to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (the first public art gallery in the Upper Midwest) where he studied under Mac LeSueur [1908-1992] the art school’s director. It was here that the young artist, steeped in circus vernacular and folk art, was first introduced to art history and the modern art movements — particularly through the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. “Having grown up constantly on the move with the circus and the rodeo, I just wanted to be stationary and produce art.”

In 1948, at twenty-two, Jensen submitted two of his paintings to the Minneapolis Art Institute of Art’s Twin City Annual. The judges were Max Weber and Alexander Calder. Not only were both works accepted, but the event proved his catalyst to shoot higher. His brother Duke had remained with the rodeo and he developed a life-long career producing his own shows. But Leo felt compelled to move to New York. He lived in a studio formerly occupied by Wilfredo Lam [1902-1982] and found work as a store window decorator for Lerner’s, the women’s apparel specialist. In 1949 the company sent him to work in New Haven, Connecticut, where he shared a spartan studio with students from the Yale School of Drama. His friends included future film director Elliot Silverstein (Cat Ballou, 1965), Sorel Booke (Boss Hogg in The Dukes of Hazzard; and, Paul Newman (dozens of major movies). He also met many of the community’s artists, including the idiosyncratic master woodcarver of totemic figures, William Kent [1919-2012], who in the 1960s invented a new medium, the slate print.

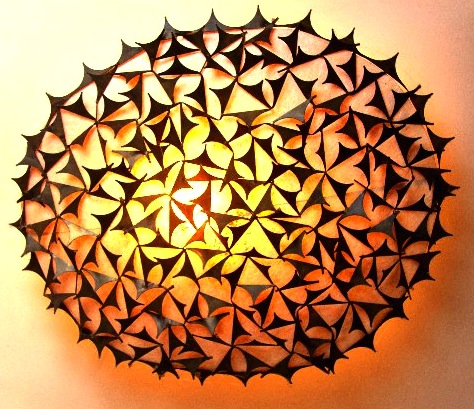

In 1952 Jensen’s sculpture made its first New York appearance, in a group show at the Creative Gallery on 57th Street. The next year the gallery gave him his first solo exhibition, featuring a dazzling panoply of sculptures in wire, copper sheets, plastic, and wood putty — the latter medium recalling his repair of carved circus wagon figures. A critic for ArtNews noted a mobile, Babylonia Garden, “which hangs from the ceiling like spraying fireworks and has a string that one can pull to make it jiggle.” And then there was Fountain Birds, “mounted on extremely long slender wire legs that cause the birds to weave tenuously with the slightest touch.” A critic for the New York Times wrote that “Sculpture as a category is too narrow to include all of Jensen’s inventive artifacts” but snubbed the artist’s “desire to be clever at all costs.” But that was exactly the artist’s intention. Like a carnival barker on the Midway, he was calling for attention. Metropolis was an irresistible amplification of the Midway in an urban setting. But this was an era when art was not supposed to be playful. The giants of the day — Pollock, DeKooning, Kline, and Rothko — were intensely introspective and dead serious. These de facto generals of the “New York School” had been engaged during and after the war in their own war with the “School of Paris.” Now they had effectively seized for New York the title of epicenter of the art world. But Jensen saw it all as rather precious and “high brow.” It would be ten years before Pop Art would burst on the scene in 1962, completely ignoring the meditative paintings of the Abstract Expressionists.

Unique in his approach to art, Jensen was never concerned about fitting in with either the “New York School” or the “Beat Generation.” Throughout his life he would remain the artist as prestidigitator, a conjurer whose purpose was amaze and delight the crowd. True to his roots, he drew inspiration from the Midway, the rodeo, and the visual vocabulary of American primitive. After all, he concluded, “to move the heart and lift the spirit is magical.” Even in his dress he was an anomaly in New York where dark charcoal gray attire prevailed. He often wore a turquoise vest, against which a Native American red-and-white glass-beaded bolo tie stood out. His socks were navy blue with white polka dots. To many, he played less the role of a New York artist and more that of an actor, like Jon Voight in the 1960s hit movie, “Midnight Cowboy.”

Encouraged by the commercial success of his first show, Jensen moved into “what seemed like the governor’s mansion” on Congress Avenue in New Haven, leasing an entire building and then sub-leasing studios to other artists. His tenants grew to include Peter Milton [1930– ], the great surrealist etcher, with whom Jensen alternated as the cooperative’s cook. He was also joined by William Skardon [1923–1983], a close friend and expressive figurativist painter who Jensen described as “one of the most spontaneous painters of our generation.” Another aspiring artist also moved in — Leo’s younger brother, Pat Jensen.

By 1954 Jensen and his friends had joined an unusual and vibrant colony — composed largely of recent graduates of Yale’s School of Art, its School of Music, and its School of Drama — based in an old icehouse on Route 1 in Westbrook on the shoreline east of New Haven. Aage Hogfeldt [1925-2014] had purchased the building, and like all of the Yale artists had earned his M.F.A. under Josef Albers [1888-1976]. The group’s concept of an artists’ colony included painters, sculptors, musicians, poets, and writers who bonded under an “art for art’s sake” credo and eschewed the New York art establishment, which they regarded as flooded with highbrow pseudo-intellectuals. Banding together, they converted the icehouse into an art gallery, painting the floors orange and covering the walls with burlap. Today, the names of these painters and sculptors, many of whom were quite accomplished, are not well known — for the very reason that they eschewed the limelight and the commercial task of promoting their art. But their unwritten credo appealed to Jensen, who having taught himself welding had turned to creating fantastical sculptures in metal — including giant surreal insects such as dragonflies and more than one-hundred figures in hand-wrought bronze — all of which found a receptive market. He also produced for the gallery a huge welded steel sculpture, Orpheus, which was placed in the middle of the adjacent pond and caught motorists gawking on Route 1. Among them was the critic Emily Genauer, who was delighted to report in the New York Herald Tribune that the Westbrook Gallery was filling a “gaping cultural lacuna” on the Connecticut shoreline. Another of those gawkers was this art historian, who as a boy was amazed by Jensen’s Orpheus, an abstract head emerging high above the water. Nearby on the edge of the pond was the monumental abstract figure, King David, by David T.S. Jones [1925-1996]. Jones had collaborated with William Kent to invent the “Slideopera,” which was presented within the main gallery. Their performances, such as The Philistine Traveler, was a huge moving slide show that integrated music, poetry, and paintings. Yale’s musical and drama performers contributed greatly to the colony, frequently performing chamber music and modern dance.1 Another artist in the group was Jensen’s wife, the surrealist painter Dalia Ramanauskas. She was born in Lithuania and came to New Haven in 1949 after a term at Displaced Persons camps in Germany. She married Jensen in 1958 and exhibited in New York at Allan Stone Gallery and OK Harris. She taught Jensen ceramics and he produced a series of fanciful birds in that medium. The Westbrook Gallery continued its success through the 1960s, attracting more viewers when Hogfeldt announced his extraordinary invention, “the world’s only 3-position camera obscura” installed in a new cupola at the peak of the gallery’s roof. 2

The 1960s: The Emergence of an Idiosyncratic Pop Artist

During the 1950s and into the early 1960s Jensen’s sculptural figures were typically described as fantastical. His seven-foot tall Apparition (1960) is even better described as surreal. A two-headed bird in hand-wrought vermiculated sheet brass pedals a steel unicycle while a headless horse tugs at the reins of his steed with one hand while waving his facemask with the other. “This is fantasy,” wrote William Kent, “not in the gruesome ‘beyond realism’ of an Ernst, but in the sense of Brancusi’s le joie pure. Here is no ‘geometry of fear.’ Je vous donne le joie pure. And it is no Victorian rider, either.” 3

When Jensen’s father died in 1955 the only item he bequeathed to his son was a pair of 2-inch high cowboy boots that he had carved. But by this time Jensen was also producing modern lighting fixtures and was represented by the interior design maven, Virginia Frankel in New York. His signature abstract welded sculpture included open work bronze table lamps, ceiling fixtures, chandeliers, pendant lights, and large room screens. These were bought by major architects and interior designers and were illustrated in House Beautiful and other home décor magazines through the 1960s. Early on, while exhibiting at one of the designer show houses he met Andy Warhol who had also arrived in New York a few years earlier, in 1949. By the mid 1950s Warhol had achieved success as a commercial artist but with only a few minor gallery shows under his belt he was anxious to find a top gallery. He would not enjoy his breakout show in New York until 1962. Now he was showing his playful rubber stamp paintings at the designer show house and asking Jensen, “How do I get into the fine art world?” Jensen advised him to meet Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg — who were working together on department store window displays at the same time Warhol was creating ads for I. Miller shoes.

“My roots are deep in the art of the circus wagon,

the Midway banner, and the carousel.”

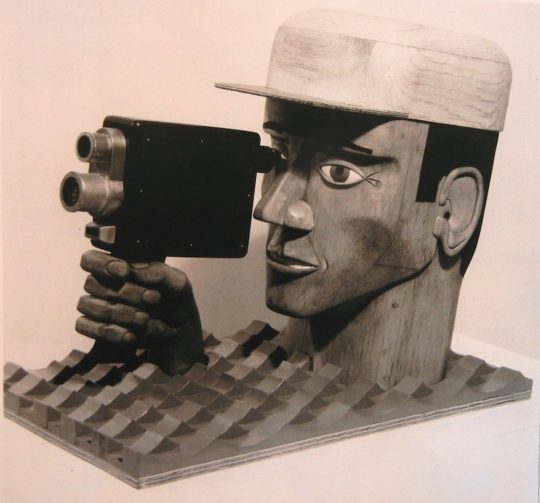

Jensen’s success in the interior design market won him some measure of financial comfort, allowing the next major stage of his sculpture to evolve during the early 1960s. As much as he had endorsed the spirit of the Westbrook colony he was the among the few who avoided the dictum of leaving New York behind. This bustling Midway retained its allure and each week he drove to the city in his Volkswagen van with sculpture in search of a gallery. On one occasion in 1962 he parked on Madison Avenue, unpacked his seven-and-a-half-foot kinetic Baseball Machine, and set it up on the sidewalk. It caught the attention of Allen Stone, who asked him to set it up in his gallery. Willem De Kooning, who was in the gallery that day, exclaimed, “That makes my painting look like mashed potatoes!” and the two went in to become good friends. Jensen was also friendly with a number of New York painters, including John Wesley [1928–], Roy Lichtenstein [1923–1997], James Rosenquist [1933–], and Tom Wesselman [1931–2004].

Jensen’s breakout solo exhibition came in 1964 at the Amel Gallery on Madison Avenue. John Canaday, the leading art critic for New York Times known for his conservatism and barbed wit, wrote that “For pure entertainment in the moment’s most avant-garde manner, the Amel Gallery on Madison Avenue has turned up with an engaging installation of pop inventions by Leo Jensen.” Continuing, Canaday called Jensen “a woodcarver crossed with a gadgeteer.” Further, without knowing Jensen’s background, he noted with surprising intuition, “They remind me of merry-go-round horses…and they are as brightly enameled.” The British art critic Gordon Brown observed that “For Europeans, the very rawness of Leo Jensen’s Baseball Machine is attractive. The lack of learned artfulness only contributes to the freshness of the work.” 4 The subject matter also attracted a rare art review from a Sports Illustrated writer who delighted in the large kinetic constructions. “Many Jensen sculptures don’t just stand there. They do something. With this one, called The Lure of the Turf, it is possible to bet win or place by spinning the dial in the center.” 5

Yes, the first kinetic sculpture was Duchamp’s readymade Bicycle Wheel of 1913. And there was Naum Gabo’s Kinetic Construction of 1920 — and Alexander Calder’s mobiles beginning the 1940s. But Jensen must be credited with inventing Kinetic Pop Art sculpture.

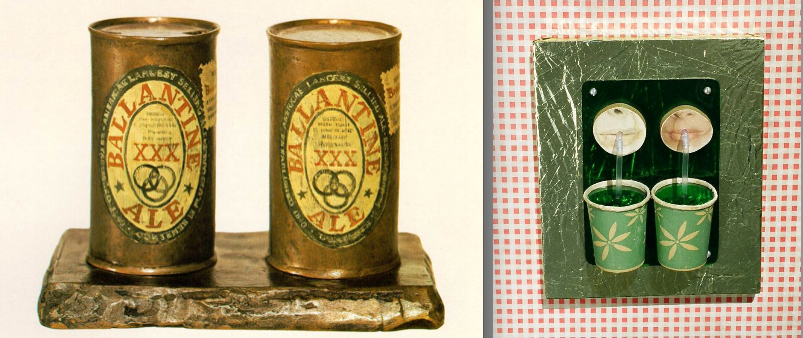

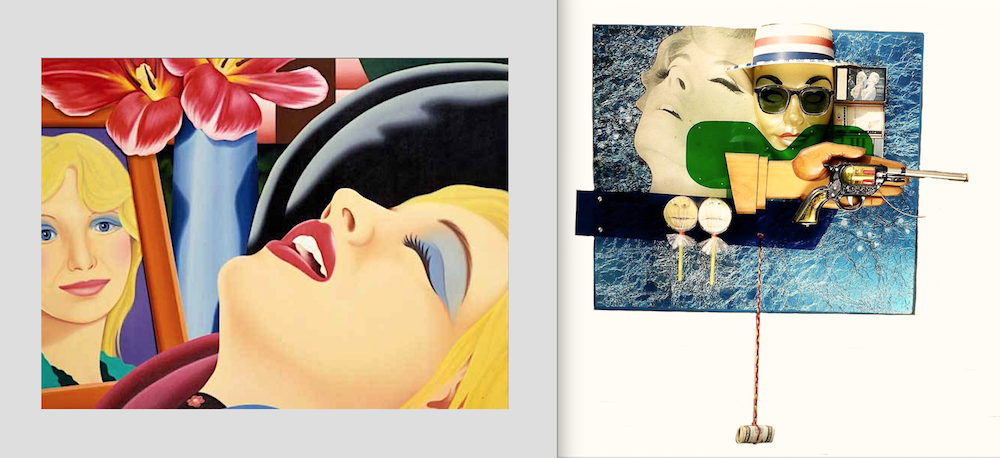

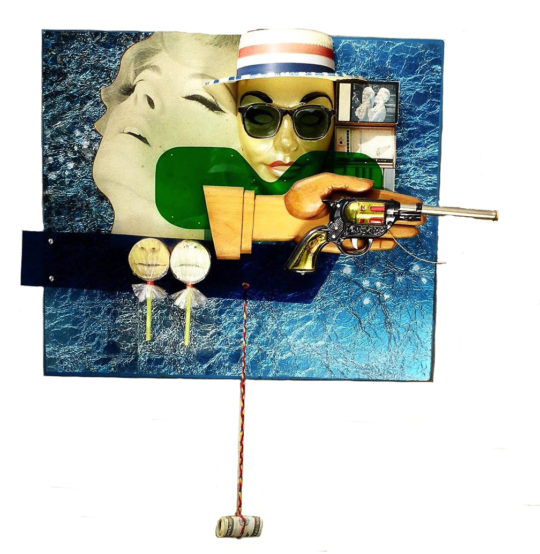

In 1965, during Jensen’s second successful solo at Amel Gallery, Wesselman took numerous photographs, remarking how he admired Jensen’s concentric halos of bright colors painted on the flat panels on which the carved and painted figures were often mounted, along with multimedia such as Plexiglas. For five years Wesselman had been developing his Great American Nude series, which in 1960 had first brought him notoriety. Now he admired the three-dimensionality of Jensen’s hanging pieces and the effective halo device for isolating the image, almost like a target. When these devices appeared in the next show of Wessleman’s work a playfully surprised Jensen teased Wesselman that he was going to conduct retaliation appropriation. The result was Sighs on the Midway. In this wall piece the head of a carnival barker wearing a red, white, and blue boater hat (perhaps a self-portrait) directly confronts the viewer. Just below at center, a carved wooden hand in folk art style holds not the expected heart but a gun, enticing the viewer to a shooting game on the Midway. The winnings, a roll of dollar bills, dangles from a multi-colored cord. The whole is mounted on a background of sparkling light blue tinfoil, featuring a large photo-collage of a blonde, her head tilted back, exuding an explicitly sensual sigh. Wesselman may have had the last laugh, however, because in 1967 he began a new series called Bedroom Paintings — and returned to Jensen’s blonde from Sighs on the Midway. For example, in Bedroom Painting #46, painted in 1977–1981, Wesselman has reversed the image of the blonde but her head is tilted back at the same angle, emitting the same sigh that would reappear in this series.

Art critics from the present era can easily make the error of over-analyzing a Jensen piece. For example, in 1964 he created a series of eight different Sippers that featured variations of a circular wood cutout upon which was placed a collage of a woman’s mouth. The lips sucked upon a plastic straw that was inserted into a paper cup with faux ice cubes. The sippers are mounted on transparent color Plexiglas and then on a wood base covered with vinyl liner paper for kitchen drawers. When this critic first saw one piece from the series — Sippers–Two Cups — it brought to mind the possibility that it may be Jensen’s parody of a famous early Pop sculpture of two beer cans by Jasper Johns, which were cast in bronze and hand-painted trompe l’oeil (Painted Bronze–Ale Cans, 1960). Jensen’s Sippers–Two Cups are the opposite. Their similarity ends with the subject matter: two beverage containers side-by-side and meant to be sipped. One is heavy cast bronze while the other is light, bright, and ephemeral, utilizing kitchen materials. But Jensen insists his creation is not a parody. Instead, he was simply attracted to using flashy materials such as color Plexiglas and a wooden disc upon which he affixed an image of lips. In addition, Jensen explained in deadpan, he always hung his series of Sippers three feet above the gallery floor, “because they should be at urinal level.”

The Heydays of Pop

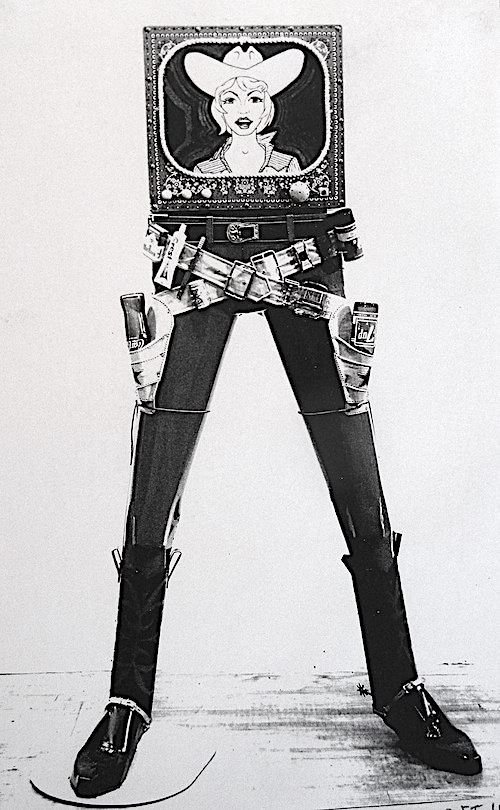

In the Fall of 1965 Arts Magazine published a perceptive article on the successful incursion of Pop Art, and as an example illustrated Jensen’s eight-foot tall electric Complete Cowboy, 1964 (Collection Phillip Morris Incorporated).

“Pop art not only typifies this new era of ‘freedom, but epitomizes its paradoxes. As a cultivated mimesis of banality (for it is not actually banal), Pop art recapitulates both America’s historical dependence upon and submission to cultivated precedent, and its hostility toward it at the same time. By emptying the contents of a lowbrow variety store into art, Pop symbolizes a demand by American art for a kind of racial inimitability and an end to ‘art for art’s sake.’ But in a formal context, it attempts a revitalization of a depleted modernist aesthetic. Thus, in proposing reconstruction by a transformation of ‘populist’ taste, Pop infers the inevitable and probably lasting ambiguities of culture in a democracy….Since Pop emerged here in force in 1962, to climax a reaction against Abstract Expressionism, the monopoly of American art by the action painters for more than a decade has broken up, the avant-garde has been decentralized, and the art scene has become as diverse and as manic as the culture boom itself.”6

The period from 1962 to about 1967 were the most intense years for Pop Art — even though at the same time Hard Edge painting had spread from California and Op Art had further served to break up “the monopoly of American art by the action painters.” In New York the harbingers of Pop were Judson Gallery (showing Wesselman in 1959) and Greene Gallery (1960–1965). But it was not until 1962 when a major gallery, Sidney Janis, became the first to mount a groundbreaking exhibition of Pop Art (the International Exhibition of the New Realists). Other major galleries that upset their stables of famous Abstract Expressionists were Martha Jackson, Stable Gallery, and Leo Castelli. Several smaller short-lived galleries also played key roles in promoting select Pop artists, such as Bianchini Gallery, Castellane Gallery, and Amel Gallery. Amel showed Jensen from 1962 until it closed around 1967. During this period conversations about Pop Art often included Jensen’s name with Lichtenstein, Warhol, and Wesselman. And in 1966 Jensen was featured in Lucy Lippard’s seminal book, Pop Art. Jensen’s friend William Kent exhibited with Castellane from 1962 until it closed in 1966. Castellane discovered and promoted two other highly original and idiosyncratic artists, Yayoi Kusama [b.1929] and Robert Smithson [1938-1973].

On the Connecticut shore members of the once vibrant colony in Westbrook had largely dispersed in pursuit of their careers and Aage Hogfeldt, their founder, remained alone. He instead turned the gallery into a fanciful world inhabited by figurative sculptures of clown busts and animal heads. Molded in concrete and painted, and typically bearing marbles for eyes, they were quintessentially kitsch. Only a few of the artists remained in New Haven. Jensen moved to Ivoryton, Connecticut, in 1966. That same year William Kent had left New York for good after Castellane closed, choosing a reclusive life in the countryside sculpting in a dairy barn. Before leaving for Georgia, David Jones berated Jensen for “selling out” to New York. That falling out must have been exacerbated when in 1967 the New Britain Museum of American Art gave Jensen a solo exhibition. By the 1970s Jensen could claim his work had been exhibited in 64 countries.

An Appropriation

The other new medium he adopted was tin. Since moving to Ivoryton he began collecting coffee cans and Danish cookie cans. He produced a series of telephones he referred to as the Caffeine Connection Pfones, some of which were more than six feet tall. Most of the tin can constructions featured various doors, each revealing surprises inside.

But his carved and painted works from the 1960s held the greatest attraction. In 1981 Jensen’s large sporting pieces were exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery’s “Champions of American Sport.” The show was highly publicized and the Jensens were invited to the White House for a reception with President Ronald Reagan. Jensen’s works were included in nearly thirty museum exhibitions (three of which were solo exhibitions) including the Minneapolis Art Institute, the Butler Institute of American Art (Youngstown, Ohio), the Institute of Contemporary Art (Boston), and Yale University Art Gallery.

In 1996 Jensen created in Eastern Connecticut what would become one of the state’s most beloved tourist attractions. The Jillson Hill Bridge spans the Willimantic River (a tributary to the Thames River). At both sides of the bridge two 22-foot tall bronze frogs with gilded eyes are perched atop bases of giant spools of thread. The huge 3,000-pound frogs, which were installed to great fanfare, constinue to surprise unsuspecting motorists. Imagine their stark contrast to the formality of the four late nineteenth century art nouveau statues of Fames in gilt bronze on both sides of the Alexander III bridge over the river Seine in Paris.

Jensen enjoyed three solo museum exhibitions; at the New Britain Museum of American Art (1967), the Mattatuck Museum (1990), and the Amarillo Museum of Art (2010). He has been included in nearly thirty museum group exhibitions, including the Minneapolis Art Institute, the Butler Institute of American Art (Youngstown, Ohio), the Institute of Contemporary Art (Boston), the Yale University Art Gallery, the National Art Museum of Sport, and the National Portrait Gallery. Yet throughout his career his work has asserted the power of the vernacular. He asks us to imagine the great number of unknown vernacular artists, typically self-taught, now neatly categorized by the art market as “Outsiders.” They produced images not for the upper strata of society but for ordinary folk. While not an Outsider, Jensen grew up in the vibrant environment that is the Midway, drew from the old-time circus vernacular, and delighted in adapting it and intensifying it for modern times. Happily challenged with being an artist who was always “inside-out,” Jensen continues to enter his studio every day with the Midway on his mind. His art is his bandwagon — that harbinger announcing the coming of the circus — and it remains brilliantly carved and painted.

— Peter Hastings Falk

FOOTNOTES

1Yale’s musical performers who were active with the colony at Westbrook included W. Christian Sidenius, later the founder of the Lumia Theatre in Newtown and author of “Lumia Kinetic Art with Music: My Theatre of Light” [Leonardo, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1982]. There was the contrabassist virtuoso, Bertram Turetzky (later professor at the University of California at San Diego) and his wife, Nancy Turetsky, the flutist. Bernard Lurie, the recently retired Concertmaster of the Hartford Symphony and Connecticut Opera Orchestras, was also a professor of violin at the Hartt School of Music. Samual Yaffe later taught Piano and Music Theory. Paolo Gruppe, brother of the famed Rockport painter, Emile, was a master cellist; and, his brother Camille, played the violin. Rheta Naylor (later Smith) played the oboe and later taught in Philadelphia. The Dutch composer and clarinetist, Walter Hekster, performed in the Netherlands Wind Ensemble as well as the Connecticut Symphony Orchestra and became widely published. He was joined by his wife, the bassoonist, Alice Hekster-van Leuvan.

2 Hogfeldt created his huge 3-position camera obscura in 1962. For position #1, he invited people to ascend a magnificent spiral staircase he made from industrial wooden pallets, bolted together and suspended by aircraft cable. At the top, one entered into the loft camera box, which turned on a revolving mirrored turret. The surrounding aerial view of Long Island Sound and environs was reflected as a motion picture on an eight-foot circular table top on the gallery floor below. For position #2, the same pictures could be seen on a fine screen stretched high above the circular table. For position #3, a large mirror on the floor picked up the motion picture again, this time from the overhead screen.

3 “Sculptor Leo Jensen” (by William Kent, writing under his pen name, Guido di Mezzavane, in Sculpture News Letter, Philistine Press, New Haven, Spring, 1961)

4 Gordon Brown, “The Emergence of an American Art” in Art Voices from Around the World, Feb., 1964)

5 “Scorecard: Sport in Art Again,” Sports Illustrated, February 17, 1964

6 Sidney Tillim, “Art au Go-Go, or, The Spirit of ’65,” Arts Magazine, Sept-Oct, 1965, p.38-40

No Events Found.

-

DETAILS

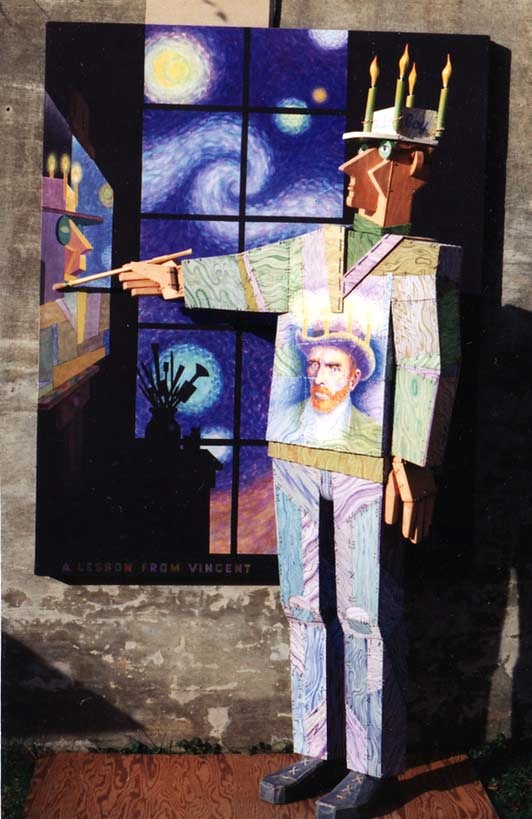

DETAILSA Lesson from Vincent, 1995

60 x 81 inches (152.4 x 205.74 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBaseball Machine, 1963

76 x 90 inches (193.04 x 228.6 cm) -

DETAILS

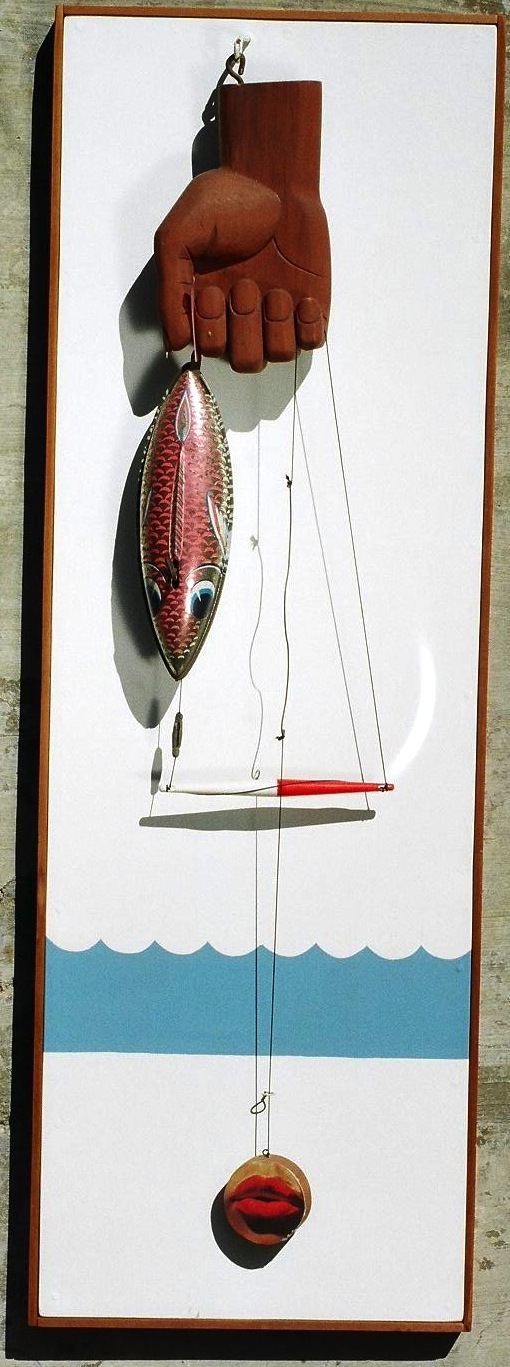

DETAILSBig Fish Eat Little Fish, 1987

99.5 x 57.5 inches (252.73 x 146.05 cm) -

DETAILS

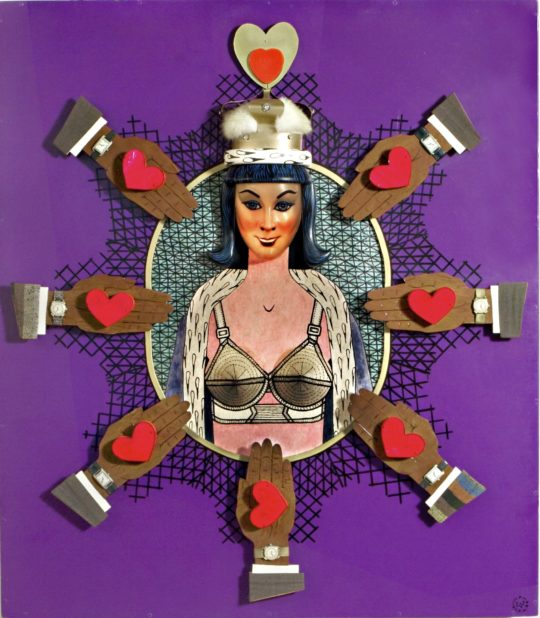

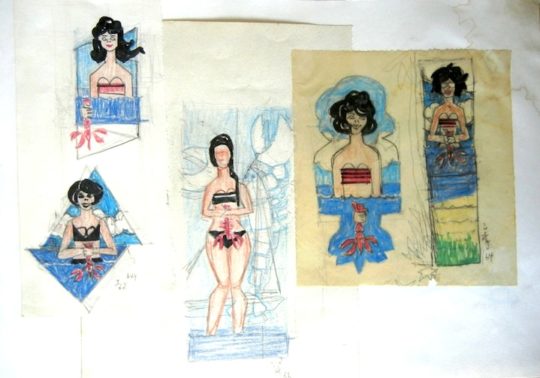

DETAILSBrassiere Dream, 1964

48 x 40 inches (121.92 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

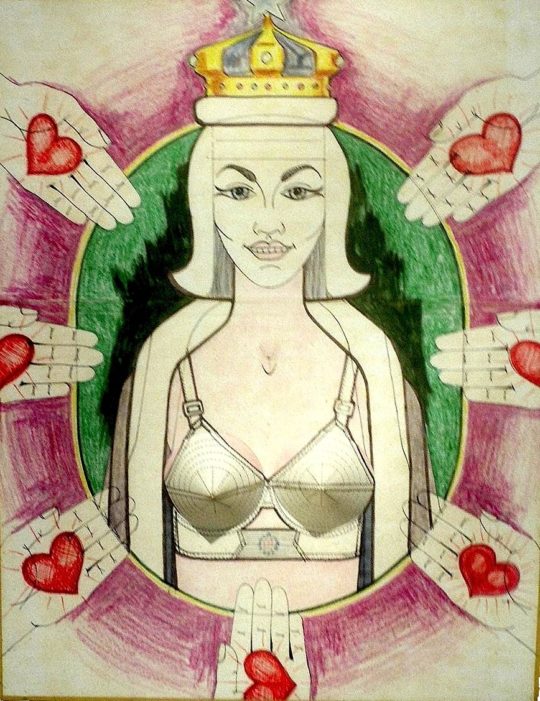

DETAILSBrassiere Dream (maquette), 1964

16 x 16 inches (40.64 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBrassiere Dream (study), 1964

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm) -

DETAILS

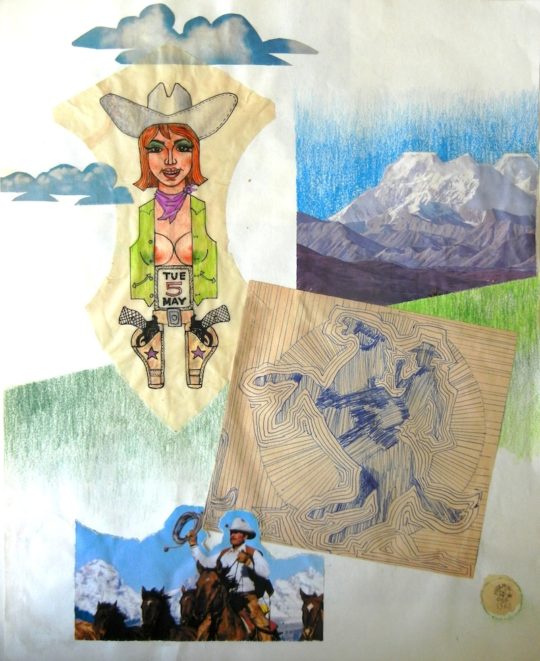

DETAILSCowgirl, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSExecutive Flight, 1964

79 x 65 inches (200.66 x 165.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFish Story, 1965

12 x 36 inches (30.48 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

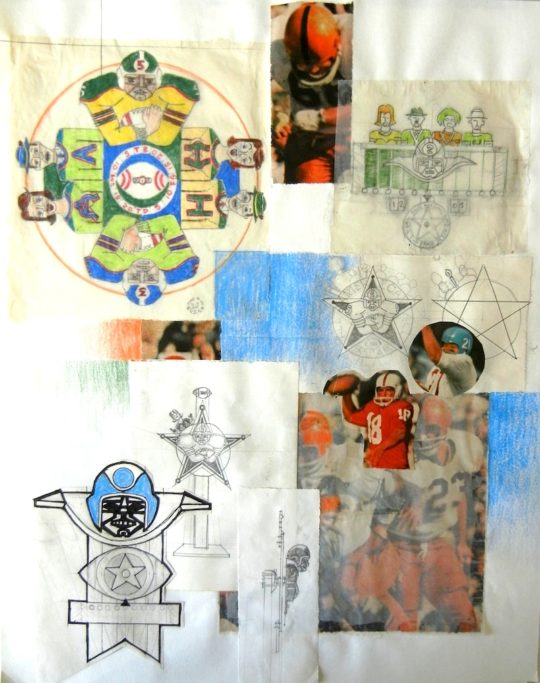

DETAILSFootball machine, 1963

67 x 96 inches (170.18 x 243.84 cm) -

DETAILS

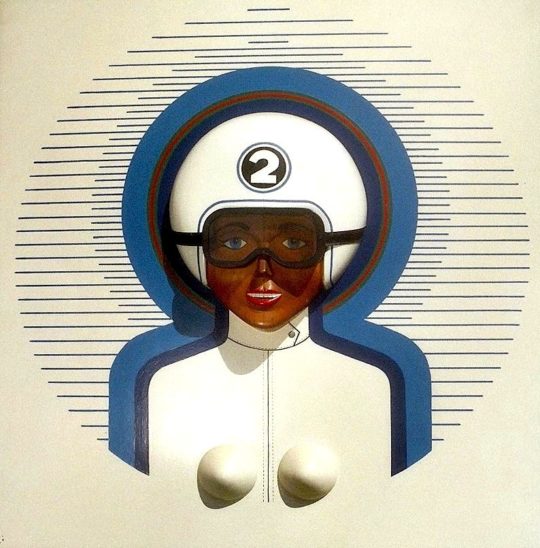

DETAILSGirl in Crash Helmet, 1964

41 x 39 inches (104.14 x 99.06 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGirl in the Sea, 1965

33 x 37 inches (83.82 x 93.98 cm) -

DETAILS

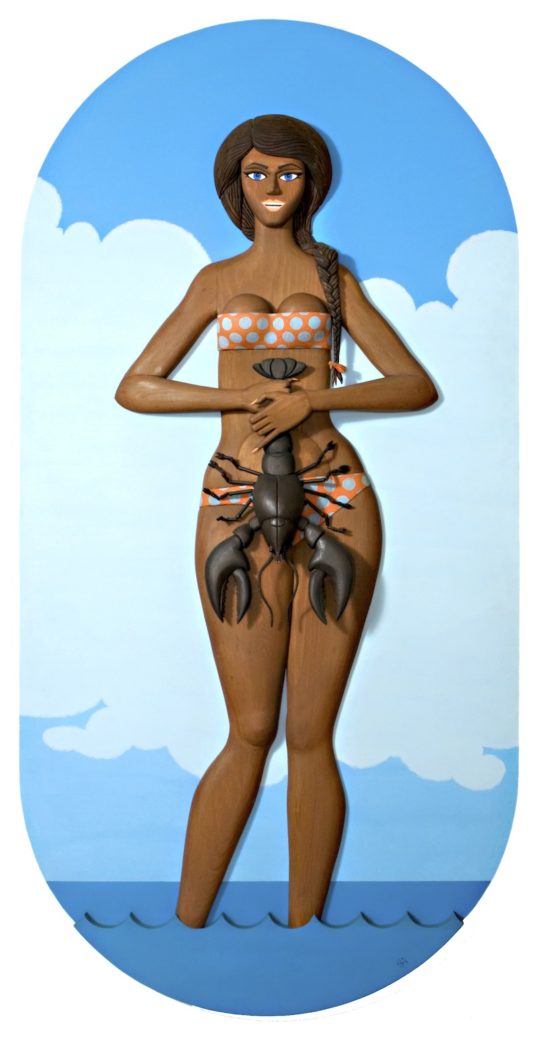

DETAILSGirl with Lobster, 1965

48 x 84 inches (121.92 x 213.36 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSKing of Clubs, 1963

39 x 96 inches (99.06 x 243.84 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSLure of the Turf, 1963

63 x 90 inches (160.02 x 228.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSModel, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

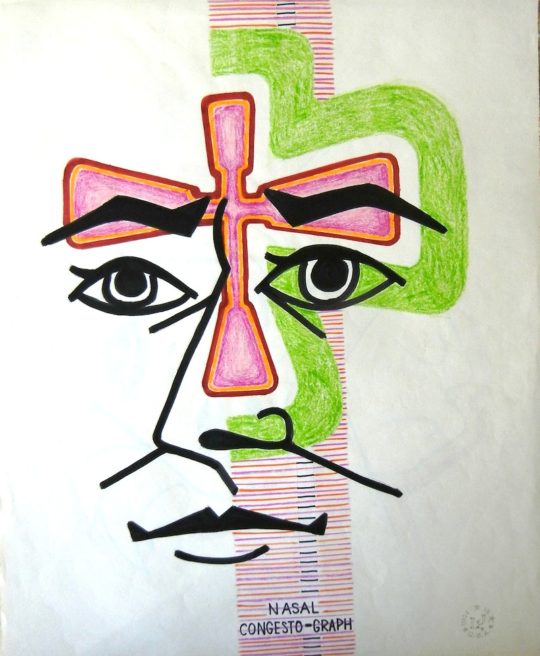

DETAILSNasal Congesto-Graph, 1964

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSRoyal Beauty, 1964

46 x 46 inches (116.84 x 116.84 cm) -

DETAILS

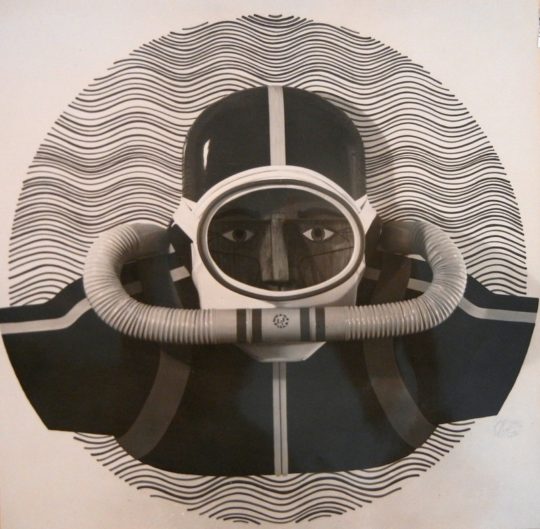

DETAILSScuba Diver, 1964

44 x 44 inches (111.76 x 111.76 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeascape, 1965

14 x 19 inches (35.56 x 48.26 cm) -

DETAILS

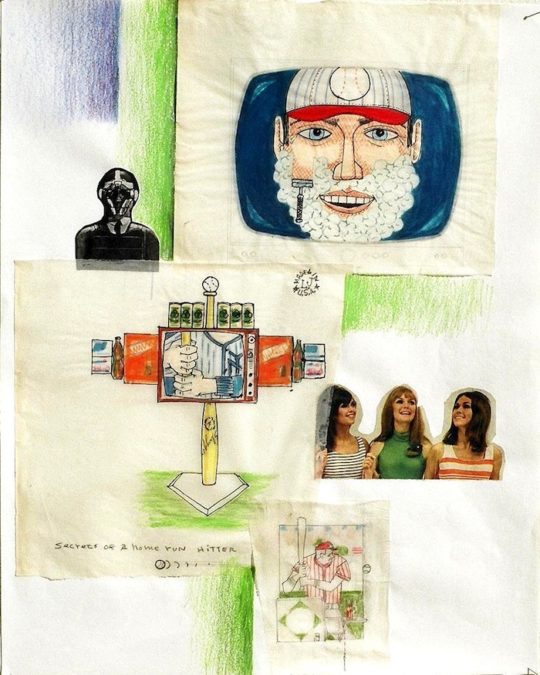

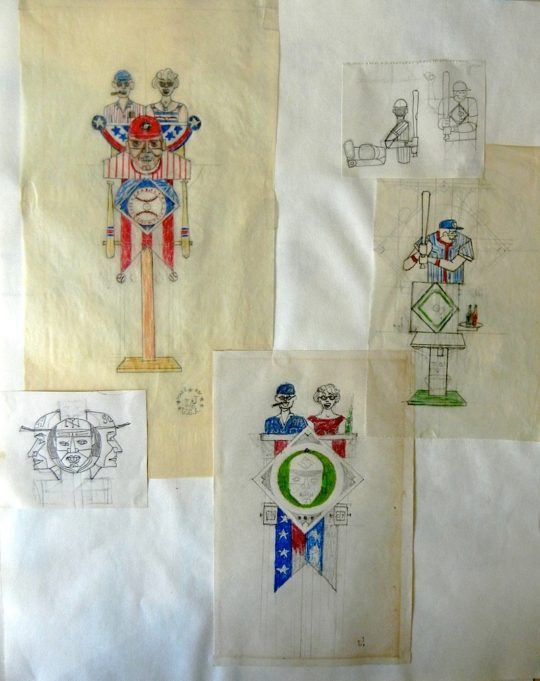

DETAILSSecrets of a Home Run Hitter, 1964

40 x 39 inches (101.6 x 99.06 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSecrets of a Home Run Hitter (study), 1964

13.5 x 16.5 inches (34.29 x 41.91 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSighs on the Midway, 1965

27 x 29 inches (68.58 x 73.66 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSippers – Three Cups, 1964

24 x 11 inches (60.96 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSippers – Two Cups, 1964

10 x 12 inches (25.4 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

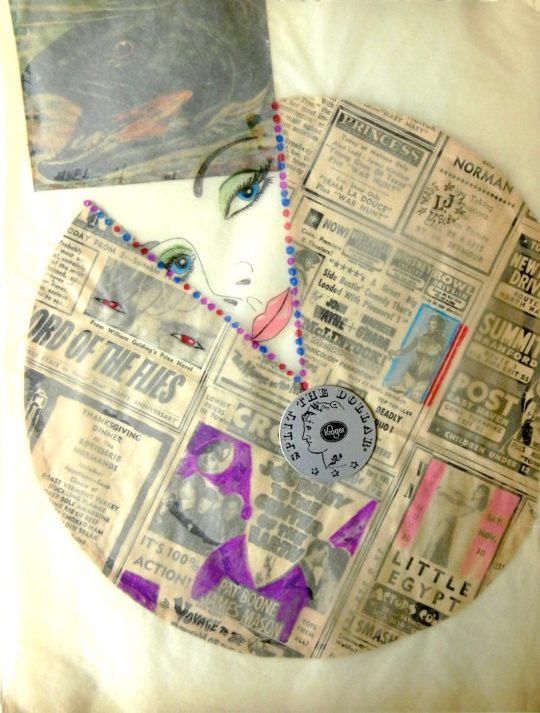

DETAILSSplit the Dollar, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSprite, 1964

39 x 73 inches (99.06 x 185.42 cm) -

DETAILS

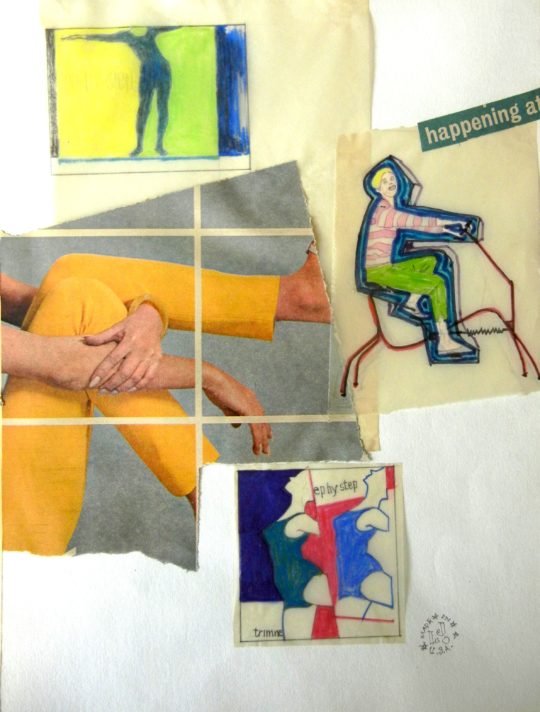

DETAILSStep by Step, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for Football Machine, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy for Lobster, 1965

16 x 12 inches (40.64 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

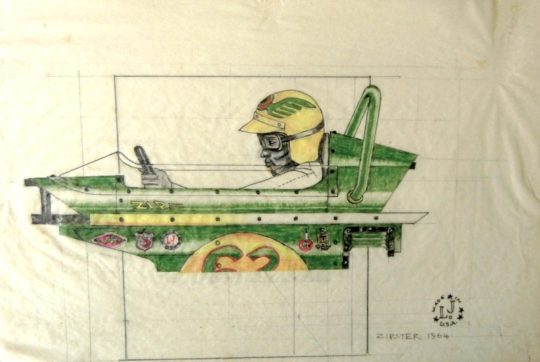

DETAILSStudy for Zipster, 1964

16 x 12 inches (40.64 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

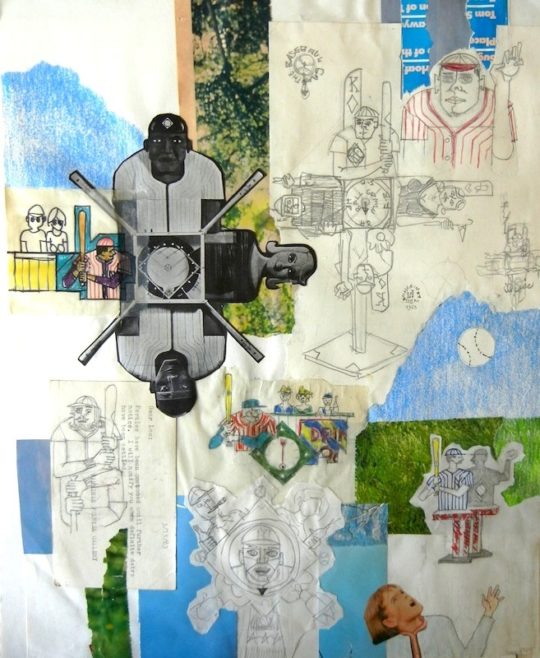

DETAILSStudy No. 1 for Basebal Machine, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStudy No. 2 for Baseball Machine, 1963

12 x 16 inches (30.48 x 40.64 cm) -

DETAILS

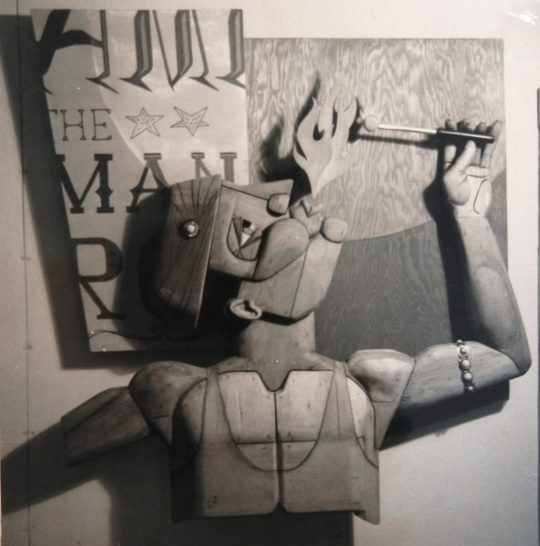

DETAILSSwami, The Human Torch, 1962

42 x 42 inches (106.68 x 106.68 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Complete Cowboy (Philip Morris Corp Collection), 1964

48 x 96 inches (121.92 x 243.84 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Frog Bridge at Windham, Conn., 2000

72 x 120 inches (182.88 x 304.8 cm) -

DETAILS

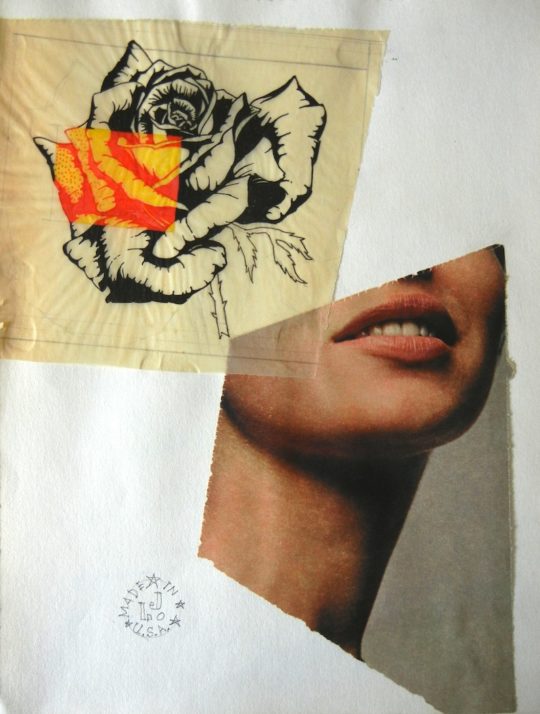

DETAILSThe Rose, 1965

9 x 12 inches (22.86 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Suitor, 1993

34 x 63 inches (86.36 x 160.02 cm) -

DETAILS

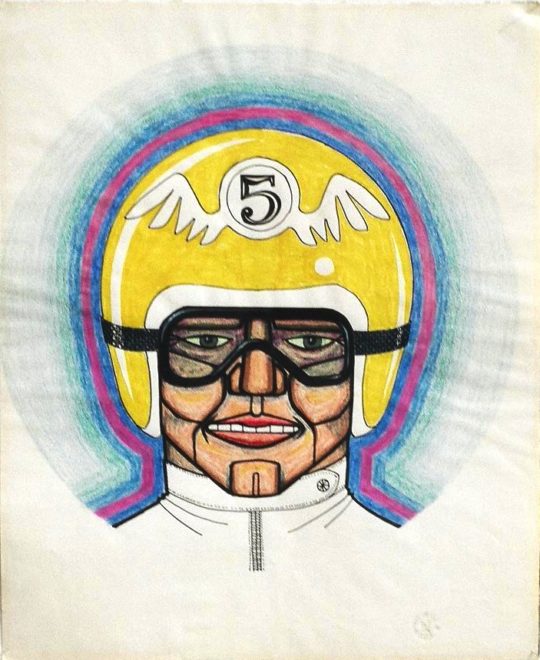

DETAILSWhite Eagle 5, 1964

14 x 17 inches (35.56 x 43.18 cm)

No News found.

[The following essay was written by Estera Milman in 2008 and first appeared in the brochure for the Jensen retrospective exhibition she curated at the Amarillo Museum of Art, October 9, 2010 – January 2, 2011]

Since the early/mid 1960s, when Leo Jensen was first counted as a major player in the burgeoning Pop Art community, his artifacts, constructions, oversized interactive games of chance and two dimensional works have occupied the complex cultural space between Pop Art and the authentically vernacular. One example, a reproduction of Jensen’s kinetic construction, The Lure of the Turf (fig. 2), appears in Lucy Lippard’s pivotal text, Pop Art (1966). Lippard describes the piece as “[vulgarized] total… Pop Art,” here echoing John Gruen’s 1964 description of Jensen’s oeuvre as “gaudy, witty [and] highly sophisticated” (New York Herald Tribune). Numerous other references to, and reproductions of, Jensen’s early Pop pieces regularly appeared in the mainstream art press. To cite but a few examples, John Canaday had singled out Jensen’s one man show at the Amel Gallery on Madison Avenue for special notice in the Sunday, February 2, 1964 issue of The New York Times, describing the exhibition as “pure entertainment in the moment’s most avant-garde manner [and] an engaging installation of pop inventions.” In keeping with Jenson’s democratic agenda, The Lure of the Turf was also reproduced in the February 17, 1964 issue of Sports Illustrated, the Fall 1964 issue of Horizon, and the February 13, 1964 issue of New York’s Daily News. Each of these publications also included reproductions of Jensen’s Baseball Machine (fig. 3).

Baseball Machine also served as the primary illustration for the “Editorial Commentary on Current Exhibitions” in the February 1964 issue of Art Voices From Around the World. Gordon Brown opens his commentary, “The Emergence of an American Art,” with the observation that “American values are in the forefront in recent shows and in the talk of the artists who are creating the art of this decade.” Prior to commenting on the “Environments by Pop artists Oldenburgh, Segal, Dine and Rosenquist” on view at the Janis Gallery, Brown posits:

For Europeans, the very rawness of American Leo Jensen’s “Baseball” is attractive. The lack of learned artfulness only contributes to the freshness of the work. America is the new frontier… American popular art has inspired an entirely new school of sculptors and painters, who constitute the most controversial, but probably the most promising, artists of the new generation. Thirty-eight year old Leo Jensen typifies the United States and its varied background.

Under the heading, “His Sculptures Don’t Just Stand There,” the lengthy “Daily News Special Feature” on Jensen also celebrated his “outsized moving sculptures… as the newest arrivals on the pop scene.” The Daily News was also quick to point out that more than half of the “monumental, kinetic sculptural art objects” included in Jensen’s first one man show in New York had already been sold, “mostly to collectors such as Ivan Karp, John G. Powers, Henry Reichmann, Mrs. Henry Luce III, and Edward Scripps II.”

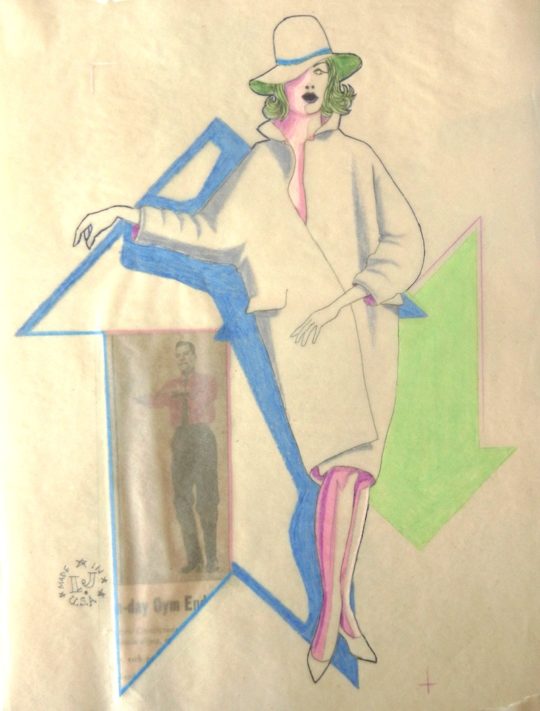

In 1965, Jensen’s Royal Beauty (fig.4) would appear in a Courreges-inspired fashion shoot for the “Women’s” section of the New York World Telegram and Sun (February 16, 1965) and in another, less high-end, fashion spread in the Milwaukee Sentinel (April 7, 1965); Brassiere Dream (fig. 5) would concurrently appear in the October 31 issue of The New York Times’ Book Review (replete with the caption, “Scoring with a dozen women”), as would a number of other of Jensen’s anti-hierarchical, Pop Art constructions.

In March of that year, Jenson was included among the participants in the group show “Pop and Circumstance: New York’s Largest Showing of Pop Art,” alongside Richard Artschwager, Allen D’Arcangelo, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Allen Jones, Alex Katz, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Mel Ramos, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, Robert Watts, and Tom Wesselmann, among others. Jensen’s Sprite (fig. 6) and The Complete Cowboy (Collection Phillip Morris Corporation) were counted among the four representative pieces lent by the Amel Gallery to this collaborative, artworld-supported fundraiser for the City of New York. Other galleries who contributed work to the show included the Richard Feigan, Leo Castelli, Stable, and Green galleries.

In “Hop, Skip and Jump” (The New York Times, February 2, 1964), John Canaday was doing his best to cover his bets. He compared Jensen’s highly visible and cross culturally accessible pop culture exhibition at the Amel Gallery to two contemporaneous exhibitions at the Perls Gallery (one dedicated to works by George Rouault; the other to 14 other members of the, so called, School of Paris) and to a concurrent showing of sculpture by Francesco Somaini (who he described as “one of the best sculptors at work today”) at the New York branch of the Galleria Odyssia. Having identified Jensen’s work as part of “the moment’s most avant-garde manner,” Canaday describes the artist as a “good craftsman who fulfills his chosen range without pretension” and voices his assumption that the Jensen himself probably did “not think that his art was world-shaking.” The conservative critic further argued that the Jensen’s great appeal was that his work made “a first impression, more and more unusual in Pop art, of complete good humor without dubious innuendo.” Interestingly, Canaday did not close his review by referencing either Rouault or Somaini, but instead by somewhat reluctantly conceding that Jensen was representative of a new world order, wherein “variety [was] not only the spice of art but also, in a civilization so many sided that it demands a multitude of expressions, the surest sign of good health.”

Similar reluctant concessions to the new art were voiced by many well-known custodians of high culture as Pop Art was being canonized. That Jensen’s works continued to be active participants in this heated cultural dialogue is evidenced in Sidney Tillim’s far more conceptually complex essay, “Art au Go-Go or, The Spirit of ‘65’” (Arts Magazine, Sept. – Oct. 1965). Subtitled, “Are today’s artists revolutionists, or mere entertainers in an act everyone’s getting into?,” Tillim’s essay addresses both the positive and negative implications of what he calls the expansion of “popular aesthetic literacy.” Toward this end, the respected critic chose only three images which he understood to be representative of post-Abstract Expressionist Art. Jasper Johns’ Flag (1954) was picked as one of the most “imaginative”examples of proto-Pop. Richard Anuszkiewicz was described as the most prominent American Op artist and his Knowledge and Disappearance (1961) chosen to represent what Tillim called an “intellectualized and incestuous… offshoot of geometric abstraction.” Importantly, Leo Jensen served as the anointed primary representative for Pop Art. Jensen’s 1964 construction, The Complete Cowboy (Collection Phillip Morris Corporation), appeared as the paradigmatic example of what the critic called the “cultivated mimesis of banality.” Tillim explains: “In more than a manner of speaking, Pop art [sic] not only typifies the spirit of this new era of ‘freedom,’ but epitomizes its paradoxes. As a cultivated mimesis of banality (for it is not actually banal), Pop art recapitulates both America’s historical dependence upon and submission to cultivated precedent, and its hostility to it at the same time. By emptying the contents of a lowbrow variety store into art, Pop symbolizes a demand by American art for a kind of radical inimitability and an end to “art for art’s sake”… Thus in proposing reconstruction by a transfusion of “populist” taste, Pop infers the inevitable and probably lasting ambiguities of culture in a democracy.

— Essay copyright Estera Milman 2006/2010