After serving in the Air Force during World War II, James Thomas studied at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1949. That summer he certainly read the August issue of LIFE magazine, which featured a 2-page spread showing the irascible Jackson Pollock in front of one of his big drip-action paintings. The headline read: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” That tongue-in-cheek headline elicited more letters than any other article LIFE received that year — and most of those letters were derisive. The public simply could not comprehend why Pollock was getting a thousand or two dollars for paintings that, as the old saw goes, “even my kid could paint.” But that article also intrigued a new generation of artists and collectors.

Here’s the back-drop. Before the war, the cultured elite would spend their money on the French Impressionists like Monet and Renoir while the intelligentsia of the avant-garde collected the early modernists such as Braque and Picasso. Now, the allied forces had just won World War II. Munich, Berlin, and Dusseldorf had been reduced to rubble. Paris was free to resume its position as the capital of the art world. But the LIFE magazine article announced a role change. It announced Pollock as the great disruptor. No sooner had Paris been freed of the Nazis than the Abstract Expressionists had won another war: New York displaced Paris as the epicenter of the art world. Rothko, DeKooning, Still, Kline and others joined Pollock in a movement whose repercussions would continue to exert their influence on generations of artists.

Thomas left for New York in 1951, inexorably drawn by the unstoppable waves of a powerful new movement that were emanating throughout the art world. He found his footing at the Art Students League studying under Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Julian Levi and their influence can be seen in his oil paintings of this period. He then returned to the Corcoran for a year before going on to compete his undergraduate work at George Washington University. Finally, he earned his MFA at Cornell University in 1955. For the next eleven years his career path appeared to be teaching art as he took positions at several colleges. At the same time he continued to exhibit with his colleagues of the Abingdon Square Painters group in Greenwich Village. But in 1966 he suddenly withdrew from teaching altogether and became increasingly reclusive, suffering bouts with deep depression and alcohol — a combination that has sent many brilliant artists into the caves of the forgotten.

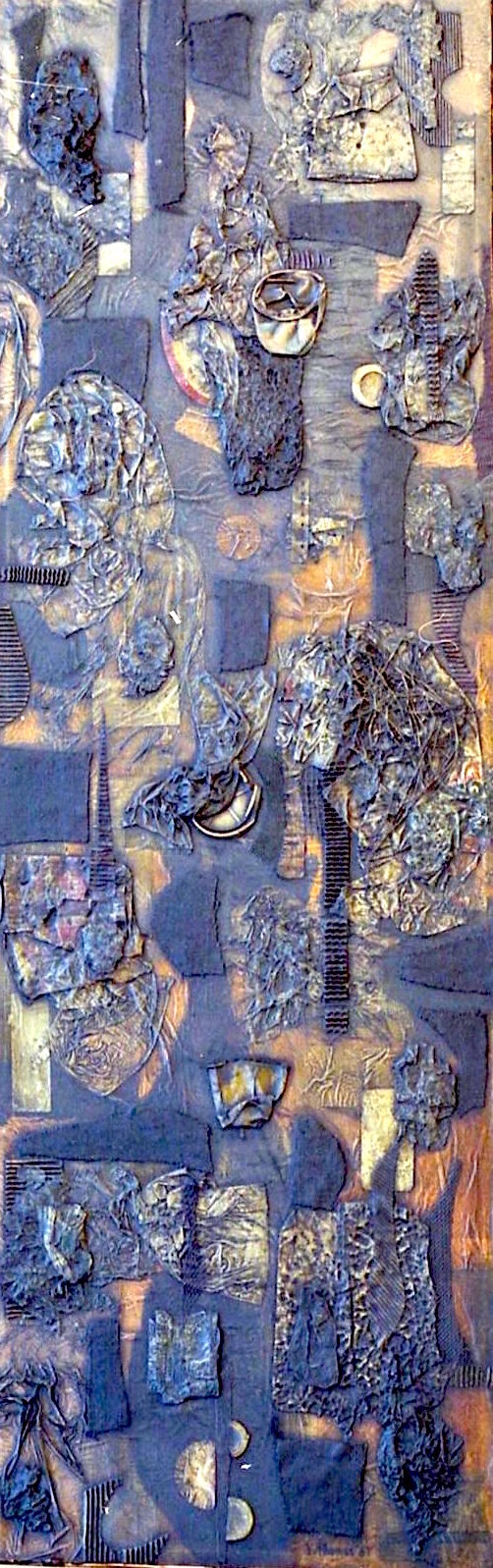

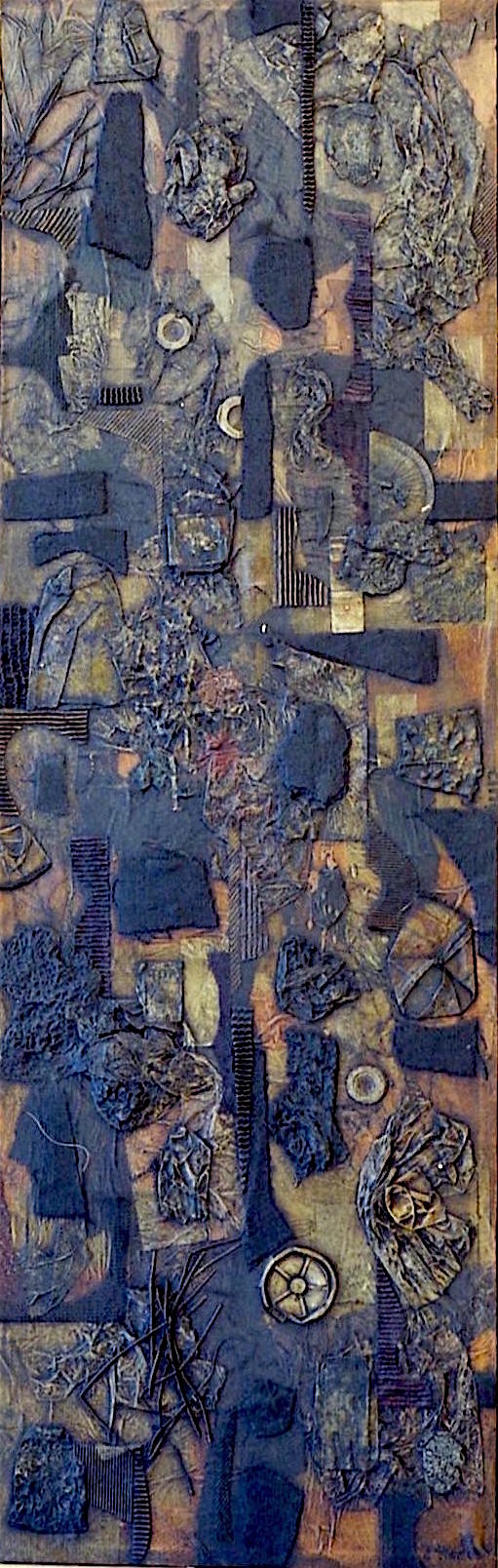

Fortunately, Thomas had discovered his artistic purpose by focusing upon collage beginning in 1963. Collage is at once medium, technique, and style — and during the 1950s it became part of an innovative and international vocabulary. It was in collage that Thomas reached his maturation despite his dark personal problems. His niece Carole Boster noted that “By the mid 1960s Thomas was working almost entirely in this medium, gluing bits of things to canvas or wallboard and then coating the entire work with a sepia wash with a tar-like appearance. He harvested the detritus of modern life, favoring bits of debris found along the roadside: nuts and bolts, shards of scrap metal, cast-off paper bags and plastic coffee cup lids.”

Willem de Kooning [1903–1997] had briefly worked in collage during the late 1940s, but this medium was most fully developed by his Italian-American colleague Conrad Marca-Relli [1913–2000]. From the 1950s and throughout his long career Marca-Relli produced large-scale collages often layered with fabric, leather, metal, or vinyl in contrasting shapes of black and dark earth tones against lighter shapes of whites, creams, and beiges. Thomas adopted a similar color scheme. Another leading first generation Abstract Expressionist who pushed the collage tradition was the Italian Alberto Burri [1915–1995] who incorporated a range of fabrics, burlap, and plastics with tar and pigments. By the mid 1950s he was pioneering the movement of collage toward assemblage as his works revealed an increasingly deeper third dimension by using plastics, charred wood, and scrap iron sheets. Joining Burri in his international impact was the Spaniard Antoni Tapies [1923–2012] who in the early 1950s began mixing non-traditional materials in a style he referred to as pintura matèrica. In New York, the collision of collage and assemblage was brought to another level from the mid 1950s to 1961 when Robert Rauschenberg [1925–2008] began to position objects emerging dramatically from the surface of his painted canvases. Pushing collage deeper into three dimensions, he called this series of assemblages “combine paintings.”

This international dialogue of collage and assemblage continued into the tumultuous 1960s, a decade when even the Abstract Expressionists — those great disruptors — were in turn upset. It was a decade of seismic consequences. All bets were off. The art world exploded with a succession of new and disparate movements ranging from Pop Art to Hard Edge and from Minimalism to Op Art. Each was an overlapping assault reacting against, or morphing from, Abstract Expressionism. Collage and assemblage were part of that assault. Thomas must have been aware of the 1961 exhibition, “The Art of Assemblage,” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which featured a range of masters from Braque and Picasso through the contemporaries Robert Rauschenberg and Bruce Connor [1933–2008]. By the late 1950s Connor had begun to push his paintings and collages into assemblages with a wide range of disparate objects never intended as art materials. Sari Dienes [1898–1992] was an important but nearly forgotten pioneer in collage and assemblage in late 1940s. During the mid 1950s she exhibited at Betty Parsons Gallery a series of collages made with found objects as well as rubbings from the city’s sidewalks on large sheets of paper. Among her studio assistants were the young Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Her works were also included in the American Federation of Arts touring exhibition Art and the Found Object in 1958-59 as well as the MoMA assemblage exhibition of 1961.

In 1963 the collage/assemblage movement caught Thomas’s imagination and he began to integrate into his compositions those flattened and crushed objects that are the refuse of our consumer culture. At this time the Arte Povera movement coming out of Italy reinforced his efforts. These artists revived the use of found objects such as fabrics, paper, rope, clothing, scraps of wood, metals, and even rocks. Arte Povera was the opposite of Minimalism and all of the other art movements concurrently vying for attention in America. Its spiritual genesis must be credited fifty years earlier to Marcel Duchamp, that pioneer of the Dada movement whose “readymade” works set the tone for generations of conceptualist artists of the 1960s–70s and beyond.

Inspired by the assemblage movement, from 1963 until his death in 1994, Thomas’s approach to collage was to utilize nature’s castaways and society’s detritus in their crushed forms, subtly projecting in bas relief from the flat picture plane. Sadly, his considerable accomplishment went unrecognized — a victim of his personal demons. Late in life he even remodeled part of his home as a gallery, as if that transformative act would in itself invite viewers. But, ultimately, Thomas must have seen himself as a castaway for no one ever saw the private gallery in his Rockville, Maryland, home that ultimately fell to the wrecking ball.

— Peter Hastings Falk, May 2016

Collage: Found Objects

-

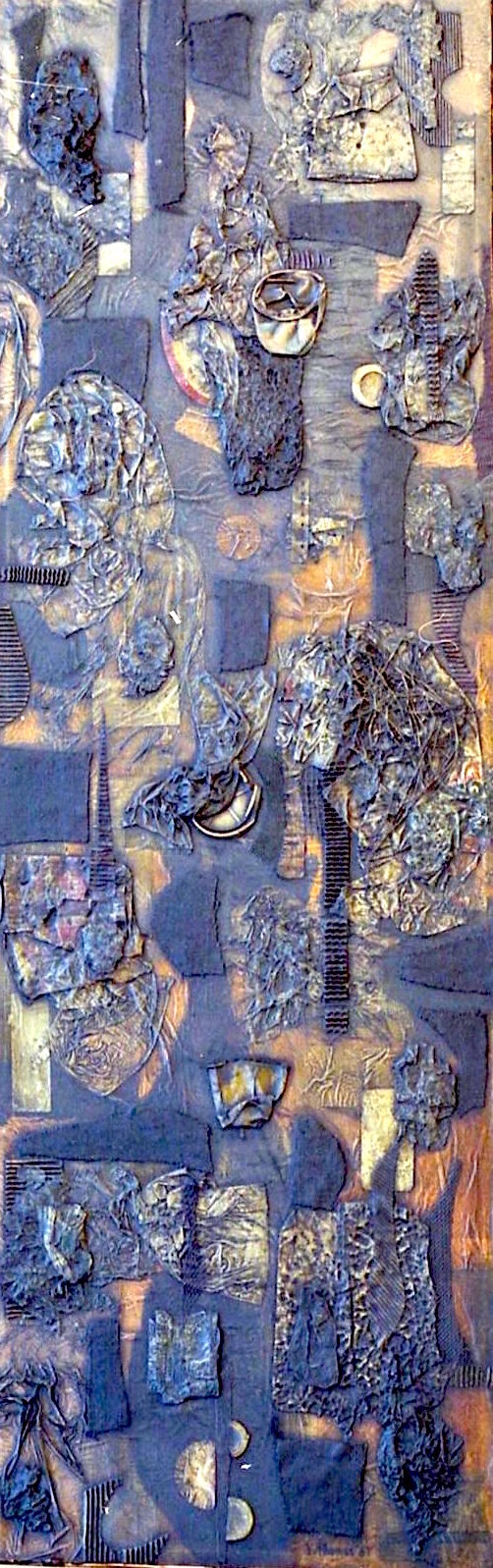

Dutch Variant, 1985

47 x 30 inches (119.38 x 76.2 cm) -

Dutchlike, 1987

17.5 x 9.5 inches (44.45 x 24.13 cm) -

Early Gem, 1965

33 x 26.5 inches (83.82 x 67.31 cm) -

Early Variant No.2, 1973

30 x 50 inches (76.2 x 127 cm) -

Early Variant No.3, 1973

35 x 50 inches (88.9 x 127 cm) -

Eighteen No.1, 1987

31.5 x 15.5 inches (80.01 x 39.37 cm) -

Eighteen No.2, 1988

48 x 21 inches (121.92 x 53.34 cm) -

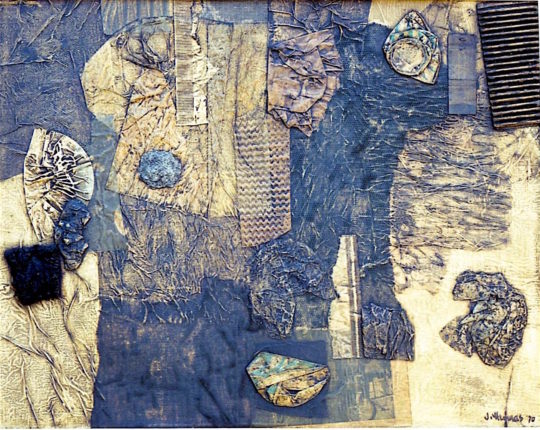

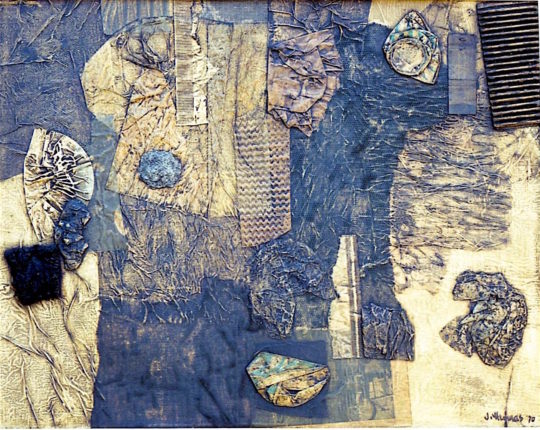

First Success, 1970

30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 60.96 cm) -

Geometric No.1, 1981

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

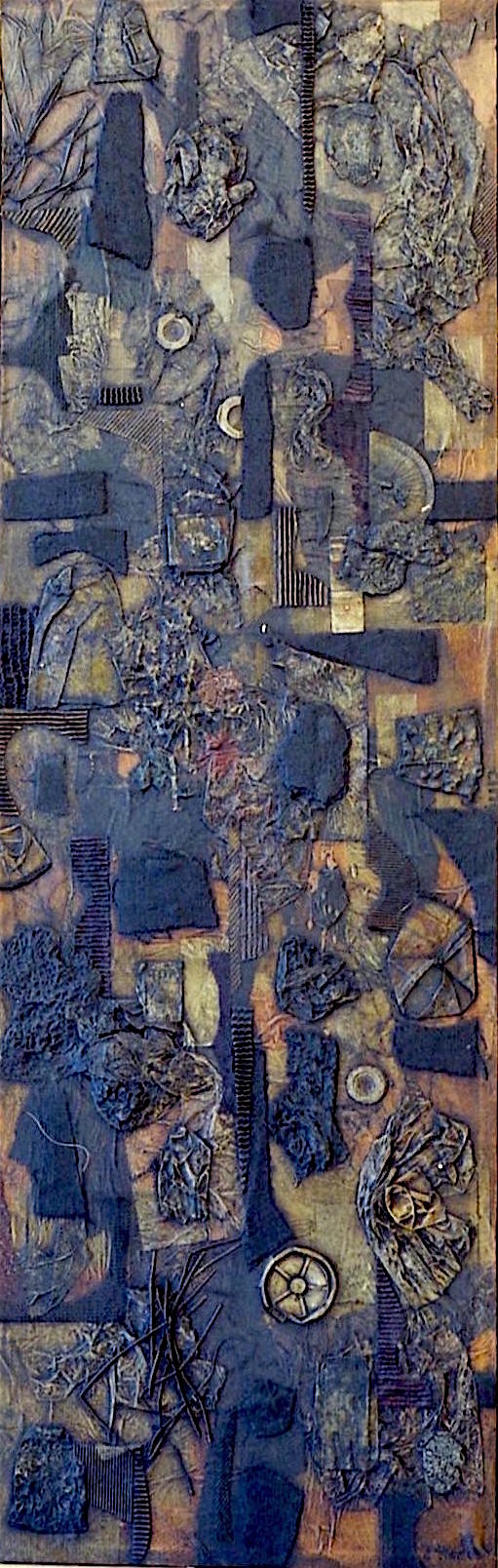

Geometric No.2, 1982

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

Geometric No.4, 1980

48 x 19.5 inches (121.92 x 49.53 cm) -

Shower of Gold, 1975

35 x 27 inches (88.9 x 68.58 cm) -

Untitled, 1980

22.5 x 8.5 inches (57.15 x 21.59 cm) -

Untitled, Diptych No.1, 1991

24 x 73.5 inches (60.96 x 186.69 cm) -

Untitled, Diptych No.2, 1991

24 x 73.5 inches (60.96 x 186.69 cm)

-

Dutch Variant, 1985

47 x 30 inches (119.38 x 76.2 cm) -

Dutchlike, 1987

17.5 x 9.5 inches (44.45 x 24.13 cm) -

Early Gem, 1965

33 x 26.5 inches (83.82 x 67.31 cm) -

Early Variant No.2, 1973

30 x 50 inches (76.2 x 127 cm) -

Early Variant No.3, 1973

35 x 50 inches (88.9 x 127 cm) -

Eighteen No.1, 1987

31.5 x 15.5 inches (80.01 x 39.37 cm) -

Eighteen No.2, 1988

48 x 21 inches (121.92 x 53.34 cm) -

First Success, 1970

30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 60.96 cm) -

Geometric No.1, 1981

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

Geometric No.2, 1982

50 x 40 inches (127 x 101.6 cm) -

Geometric No.4, 1980

48 x 19.5 inches (121.92 x 49.53 cm) -

Shower of Gold, 1975

35 x 27 inches (88.9 x 68.58 cm) -

Untitled, 1980

22.5 x 8.5 inches (57.15 x 21.59 cm) -

Untitled, Diptych No.1, 1991

24 x 73.5 inches (60.96 x 186.69 cm) -

Untitled, Diptych No.2, 1991

24 x 73.5 inches (60.96 x 186.69 cm)

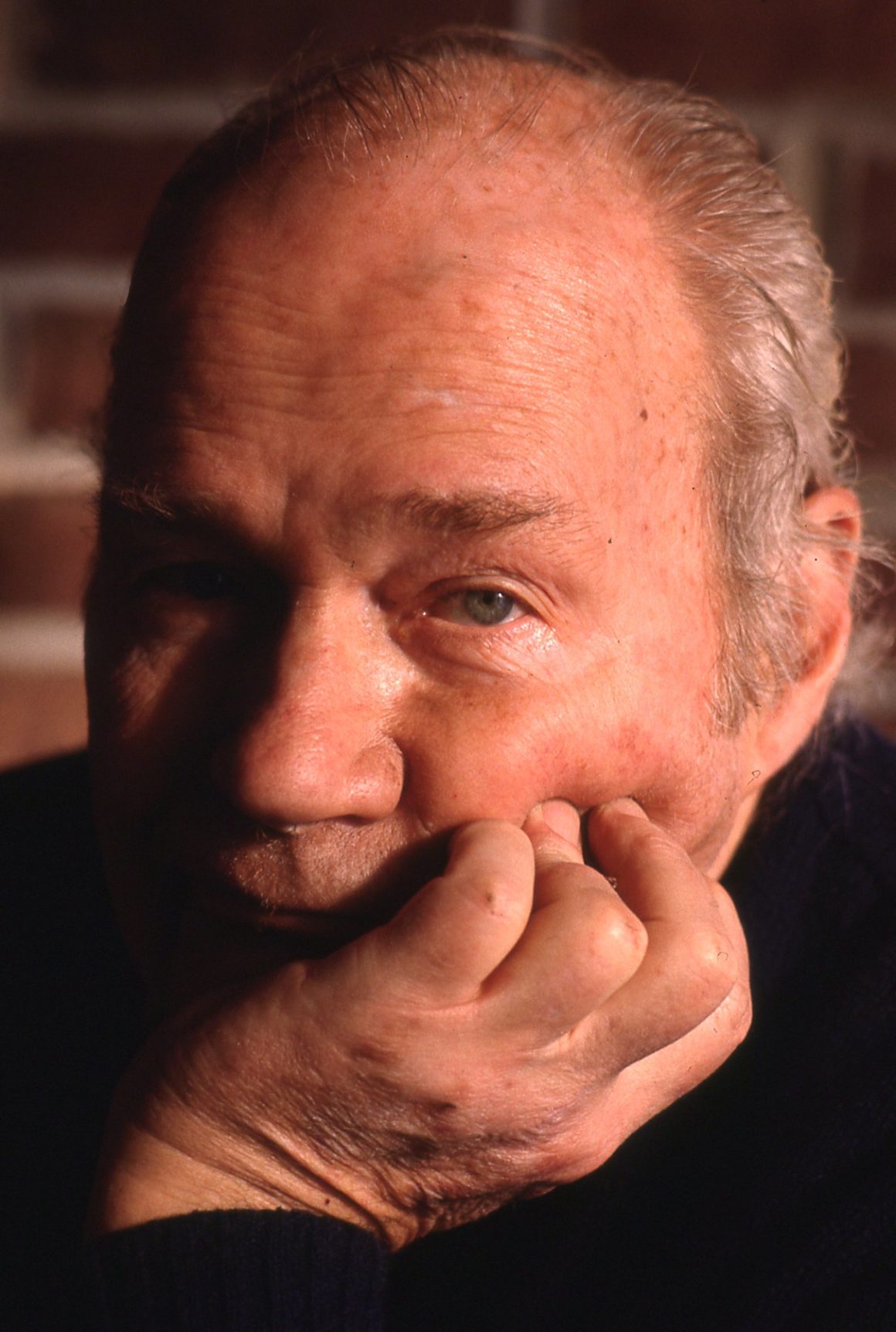

James L. Thomas, Jr. [1925–1994] was an artist both ahead of and behind the times in which he lived. He studied and painted in the avant-garde New York art world in the 1950s and 60s and was at the cutting edge of constructing abstract collages from found objects. Yet he never fully moved past the personal demons of his own childhood and adolescence. His life, like much of his art, was a study in contrasts: the intellectual stimulation of city life versus the solitude of country living, and a mid-century modernist perspective tempered by his preoccupation with the past.

Jim Thomas was born August 9, 1925 in Austin, Texas, the second child and only son of Louise Megee Thomas and James L. Thomas — both of them highly educated, but of very modest means. His mother Louise attended the University of Texas along with each of her five sisters (quite noteworthy at the time), where she graduated in 1917 with a B.A., an M.A., and teaching certification. There she met and, in 1918, married James L. Thomas, who was working toward a Ph.D. in physics. The family moved from Austin to the Washington, D.C. area in 1927, where James Sr. had accepted a job at the National Bureau of Standards. James Jr., or Jimmy, spent his early childhood years in a rented home in Bethesda, Maryland, until the family purchased a home in the nearby town of Garrett Park in 1935. Garrett Park was then more small town than suburb, a planned community developed at the turn of the 20th century as a “whistle stop” town where fathers could commute to jobs in downtown Washington by train and raise their families in bucolic surroundings. Jim was a precocious kid, and graduated from Bethesda Chevy Chase High School a year ahead of his peers in 1942, having distinguished himself in drawing, creative writing, journalism, debate team, and, according to his yearbook, “psychic bridge.”

He started his college career at the George Washington University in the fall of 1942, but then World War II intervened and the nineteen-year-old enlisted in the Air Force (followed by reserve duty until 1952). Resuming his studies at GWU on the G.I. Bill, he enrolled in a pre-law program but in 1949 was drawn back to the world of fine arts, and began studying at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. In 1951 the New York art world beckoned in the form of a National Scholarship award for study at the Art Students League during 1951–52. Jim studied with Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Julian Levi that year, then returned as a scholarship student to the Corcoran, to study under Richard Lahey and Heinz Warneke — and the school’s jury awarded him First Prize in the Carrington Class. He finally earned his B.A. in Fine Arts from GWU in 1953. From 1953–55 he attended Cornell University, teaching drawing and painting as a graduate assistant and earning his M.F.A. in Painting.

Like most gay men in the era before the Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village in 1969, Jim kept his sexuality to himself for most of his life. He never appeared in public with a partner, male or female, and only outed himself in vague terms to select family members in his later years. A brooding youth, he grew into a solitary, deeply private adult. His six-foot-four frame may have obscured, to those around him, an acutely sensitive and tortured soul. He was prone to dramatic mood swings, most likely suffering from what was then known as manic-depression. He self-medicated this condition with alcohol, especially in his later years, and at various periods during his life he was under the care of a psychiatrist. He remained an enigma to his family even as he ultimately sought refuge with them from the overstimulation of his forays into the outside world.

After leaving Cornell, Jim taught art at the high school level for a year, then worked as an art instructor at Juniata College in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, from 1957–1960. In 1960 he resigned his position, returned to New York to work professionally, and joined the Abingdon Square Painters, an artist cooperative in Greenwich Village. It was during this period that his painting style matured, and although he painted fairly prolifically during the late 1950s and early 1960s he could apparently only survive as a “starving artist” in New York for two years, whereupon he accepted a one-year teaching appointment at Arlington State College in Texas from 1962–63. He then taught for three more years (1963–66) at Madison College, now James Madison University, in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Between 1963 and 1966 he displayed his paintings at one-man shows in New York (probably through the Abingdon Square group), in Arlington, Texas, and at Madison College; there are still price tags on many of his paintings from that era, but it's not clear whether he ever sold anything.

It was only toward the end of this period of interaction with others in the art world that Jim began to experiment with collage. His first collage, Numero Uno, was created in 1963, when he had just begun teaching at Madison. However, it appears that the first collage with which he was really happy was First Success from 1970. It's ironic that the years during which he achieved his greatest artistic success (1970–1990) are also those in which he isolated himself most completely from colleagues in his field. Teaching hadn’t suited him, even at the college level, as he “did not suffer fools gladly,” in his words, and had little tolerance for mediocrity.

Whether he left his college teaching post at Madison voluntarily after three years or was denied tenure and asked to leave is not clear; but leave he did, retreating to the guest quarters in his parents’ new and very large, modern, architect-designed home in (what was then) a rural corner of upper Montgomery County, Maryland, between Rockville and Gaithersburg. His father had by then retired from government service as Chief of the Electrical Resistance division of the Bureau of Standards (where he had spent his entire career), but his parents were still only in their sixties and probably did not need Jim’s care as much as Jim needed a safe haven — or at least, an inexpensive place to live and work. Jim Jr.’s design sense may be felt in the Scandinavian modern décor throughout the Rockville house, though it was also true that James Sr. maintained professional ties with colleagues at the University of Göteborg, and both parents travelled extensively in Sweden and Denmark.

Jim set up a studio in the basement of the Rockville house and spent most of his time there, immersed in his collages, unless he was out working in his beloved gardens or shut in his room, “in a blue funk,” as he described his dark moods. On his upswings, he loved to cook and entertain a handful of close friends and family members. Mexican cuisine was a specialty and reflected his love for all things Mexican, which he had acquired on several visits across the border.

In his younger years, Jim enjoyed travel — or at least the idea of travel. In addition to his trips to Mexico, he made an annual pilgrimage to the summer colony in Vinalhaven, Maine, where some of friends lived. As he grew older, though, he became increasingly reluctant to leave home. A year or two before his death at age 69, he planned a road trip to Maine, but only made it as far as Baltimore before turning back. He never explained what had spooked him, but he remained essentially housebound thereafter, and more or less alone.

A careful look at Jim’s later, more abstract paintings and perhaps even his collages reveals a nostalgia for the past — particularly for the unspoiled landscape that surrounded his childhood home — and a sense of claustrophobic encroachment as the built world closed in around it.

Orange Landscape (1959) conjures up an image of bright sun reflecting off the undulation of what were then farm fields in back of the Rockville house; the grey patch on the left could be an office building in the distance but the small grey spot on the right seems lost, isolated, and nearly smothered or swallowed up by the bright square cubes all around it. Jim’s premonitions of what would become of those farm fields, plows and bulldozers turning them into new roads with boxlike homes on little square lots came true all too soon in the ensuing years.

Construction (1959) is more abstract, reminiscent of a child’s building-block construction, or perhaps a view of skyscrapers in New York, but at the same time it is map-like, cold and severe. A thin but boldly bright yellow rectangle (which he once said represented the increasingly busy main street through Garrett Park where he grew up) cuts through and overlaps other sharply delineated geometric shapes, almost like an architect’s plot plan.

The charcoal sketch for 14th Street, NY (1961) is constructed simply of lines, cubes, and softened shapes, but in that cityscape one gets a precarious sense of foreboding from stacks bearing down upon stacks, almost but not quite to the point of collapse, and seemingly out of balance. One could easily get lost in there. Or be crushed.

In the early 1960s, Jim began creating abstract collages from found objects. By the mid-1960s he was working almost entirely in this medium, gluing bits of things to canvas or wallboard and then coating the entire work with a sepia wash with a tar-like appearance. He harvested the detritus of modern life, favoring bits of debris found along the roadside: nuts and bolts, shards of scrap metal, cast-off paper bags and plastic coffee cup lids from fast-food restaurants, perhaps bounced from the backs of pickup trucks as they jostled along Glen Mill Road en route to their next construction job.

It is hard to know what motivated Jim to continue working in the medium of collage, as he rarely talked about his work. Certain elements recur, such as those ubiquitous white plastic coffee lids featured in collage after collage, leading one to wonder whether particular objects had special meaning to him. The plastic lids, for example, often seem hemmed in, submersed or squeezed between looming dark objects. Regardless of how much “message” was intended, the more successful collages benefit from the collision of forms, textures, and colors, which seem to change constantly, depending on the ambient light, the distance, and even the mood of the viewer.

In the 1980s Jim assumed a more active role in the care of his mother Louise (“The Aged P” he called her), as would any devotee of Dickens — and Jim had read his collected works three times through. She lived to the age of 94, and died at home after a brief illness, in 1989. In 1991 Jim finally began to turn his attention, albeit reluctantly, to documenting his oeuvre of collages and possibly getting them shown. He was from time to time in communication with Strathmore Arts Center in North Bethesda, donated a piece to them for their annual fundraiser in 1993, and had hopes of arranging a show there.

Shortly after his mother's passing, Jim also began construction of an art gallery in one of the back bedrooms of the family home. By the spring of 1994 he had started an expansion project, turning other rooms into gallery space where he planned to hang even more of his work. In a letter to a family friend in July of 1993 he wrote:

"So here I am, with an enormous white elephant of a house on my hands, which I hang onto because it gives such excellent working conditions; and because I can’t get as much for it as I want. As my sister says, the only people who could afford it wouldn’t want it. I have improved the shining hours, however, by turning what used to be my father’s bedroom into a gallery, just for me, and did a pretty good job of it, I must say, though complications have arisen and I’ll soon have to do some more work. And I am formulating other grandiose plans, which I try to ignore. If only I were twenty years younger!"

Unfortunately, no one other than the occasional visiting relative ever got to see either phase of the gallery, and on December 16, 1994, Jim was discovered dead, alone in his home, probably from a massive stroke.

One wonders, was he shying away from exposing his works to potential critics because he was afraid of failure? Or was he afraid of success?

Epilogue: The Rockville house, in an increasing state of disrepair due to “deferred maintenance” and inadequate heating in the years after the death of James Sr. in 1974, developed many structural problems twenty years later, including buckling floorboards, burst pipes, and water damage in ceilings and walls. It couldn’t be sold “as is.” Jim’s sister, Anne, had been correct that “anyone who could afford it couldn't want it.” Indeed, years earlier, James Sr. had always maintained that the real value in the property was the land, not the house. In 1999, the house and its 2.5 acres were sold to a real estate developer, who promptly razed the house and replaced it with 5 mini-mansions on a cul-de-sac, complete with an entrance gate along Glen Mill Road. Fortunately, the paintings had been removed and put in storage elsewhere and did not go under the wrecking ball along with the house.

— Carole Boster, March 2016

No News found.

No Events Found.