A self-taught sign painter in Harlem during the Great Depression, late in life this Outsider artist created a large series of collage portraits that celebrated historically significant black Americans from all professions. His portraits-as-signs engage in social commentary as they captivate viewers with colorful hand-painted text, shiny vinyl letters, and stickers.

Ed Welch: Black Portraits as Signs of our Times

I was struck by Ed Welch’s signs-as-collages after they were exhibited at the Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore in 2003–04. Beginning in 2006, I visited and interviewed Ed four times until his passing in 2011 at 93. Throughout this period, he mailed me dozens of letters and photocopies of his project designs. Late in life this self-taught sign painter — a true Outsider — had created hundreds of collage portraits that celebrated historically significant black Americans from all professions. His portraits-as-signs captivate viewers with colorful hand-painted text, shiny vinyl letters, and stickers — often leading them to his social commentary about race relations.

Ed Welch was born in 1918 in Winfall, a small town at the top of an inlet off of the Albermarle Sound in North Carolina. He attended a local a one-room schoolhouse where the kids ranged widely in age. He had to walk to school because only white kids were allowed to take the school bus. Eventually, someone donated a flatbed truck and mounted a wooden seating structure on it. “We were excited because it was even enclosed with glass windows. That was our new bus!” he exclaimed. His childhood was not a happy one. “I was neglected as a child,” he said. “My mother was one of eight children, and she had been neglected. She destroyed daddy and me.” Beginning at age 7, he picked cotton after school. “I was paid 1 cent per pound” he said, “So, I could make 30 cents in one day.” It was also at age seven when Ed experienced an epiphany. On a break from picking cotton, as he sat in the shade beneath a big tree, he noticed a cicada on its trunk. The cicada was in its nymph stage about to molt, and as he watched its shell began to crack. Then the mature cicada gradually emerged. “I believed I was witnessing a miracle — as if I alone had been chosen by God to see it. It was a sign of the promise of rebirth.” That experience would manifest itself late in his life.

Ed got his first sign painting job when he was twelve. He had been doing chores for the local grocery store and noticed that they pasted paper signs about their goods in their windows. One day, when the local sign painter failed to show up, Ed confidently proclaimed that he could fill his shoes. The store owner loved Ed’s signs and paid him $2 a week. From that point on, Ed knew he would become a sign painter. In 1931, just as the Great Depression was taking its relentless toll throughout America, his mother moved with her thirteen-year-old son to New York and they settled in Harlem at 138th Street. However, Ed’s poor reading abilities placed him back in the 1st grade. Determined to self-educate, he recalled spending so many hours reading the encyclopedia bent over his desk that he regularly developed sores on his chest from rubbing the desk’s edge. To his delight, in junior high school he was greatly influenced by a teacher of sign painting at P.S. 139 in Brooklyn. He then attended two high schools in New York: Brooklyn Technical High School and The High School of Art and Design.

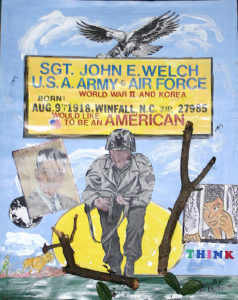

Upon graduating in 1937, he got a job working for the WPA’s Federal Art Project. The next year he joined the U.S. Army’s 9th Cavalry and trained in Fort Riley, Kansas, famous for its cavalry regiments of “Buffalo Soldiers.” He married at the outset of World War II just before shipping out to the European theatres. He was part of the North African Campaign and when in Casablanca witnessed widespread slavery as well as pervasive anti-Semitism. A Sergeant in the tank corps, he then moved on to the Italian Campaign where, because he quickly became fluent in Italian, also served as an interpreter. In 1946 Ed returned to New York, living in Tribeca and serving in the Army Reserve as “Critical MOS” (military occupational specialty) training recruits and teaching graphics and sign painting. At the same time, he became certified at New York University as an instructor in the industrial arts. He also studied drafting at Virginia State College (now University) on the G.I. Bill. Returning to Harlem, he started his first sign-painting business, “Star Sign Co” with the motto “A business without a sign is a sign of no business.” He soon had two employees, and success for the business was because “I took a bucket of stickers and stuck them on the doors and windows of every store in Harlem. One guy called me very angry, telling me to ‘take those goddamn stickers off my door!’ I came right away, apologized, and said I had just returned from the U.S. Army. My being in the service changed everything and I wound up making the guy a sign.”

In 1950 Welch enlisted the Korean War as an Airman First Class in the newly-formed U.S. Air Force and wound up at the 38th Parallel — the border between North and South Korea. After his discharge in 1955 he settled in Newport News, Virginia, and started his “Quick Sign Co.” Despite four marriages he never had any children. “Because of cunningness on my mother’s side of the family I did not want to reproduce. I was afraid of a genetic problem from my mother. I’m not like my mother’s people at all….I even bought a house for her but she burned it down.”

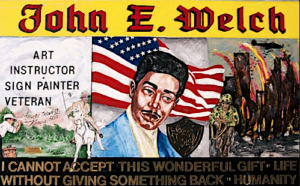

After retiring in the late 1980s, this self-taught artist transformed his sign-making style to begin creating a series of portraits that celebrated historically significant black Americans from all professions. Each work is a poster-size collage, typically painted on heavy cardboard or wood. He would then add explanatory hand-painted text, shiny vinyl letters, and stickers. Glitter was often applied, and he even attached objects he felt best completed his biographic portrayal of the celebrity. Among the many notables in his portrait collection were George Washington Carver, Rosa Parks, Joe Louis, Ray Charles, Jesse Owens, Muhammad Ali, Malcom X, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Al Green, and Janet Jackson. He also created signs that promoted social concepts.

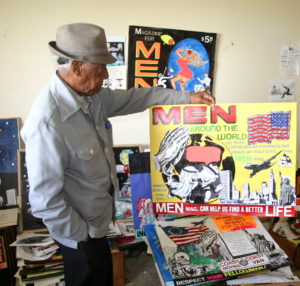

For example, he dreamed of publishing a magazine called MEN. To promote the concept he showed me a sign that seemed as if it was promoting a strip club. But he quickly explained, “I created this Big Apple sign with a sexy dancer as a lure for my MEN magazine. Once you get them hooked and they are inside the magazine, we ask them questions like, ‘Are you taking care of your kids?’ This is how we get their attention for the real serious issues.” He often signed his works with a modest mailing label whereas he typically signed his letters “Sergeant J. Edward Welch” in pride of his military service. In 2010, Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York held a solo exhibition describing his works as “Exuberant, colorful and multi-textured, each of Welch’s mixed-media paintings is a mini-spectacle conveying snippets of social commentary and plain-spoken philosophy that reflect the artist’s voice of experience and his engaged — but never weary — view of the world.”

In 2006, at age 88, Welch developed several inventions — all of which focused on death and rebirth. They also required substantial venture capital that he was never able to raise. “The anti-mine machine is a gold mine,” he declared. “It operates on batteries with a pendulum mechanism and is powerful enough that you don’t know where it’s going to roll. But it is magnetically attracted to the mines and blows them up. It can also be used as a toy — You’ve just got to remove the spikes. Kids and dogs would love to chase it.” Another invention was an eco-sensitive crematorium. It held four chambers to process the body, but instead of sending emitting polluting smoke into the air the ash particles would be mixed with water vapor and returned to the earth as fertilizer. Still inspired by his childhood epiphany from the cicada, his most poignant project was “You Don’t Have to Die.” In 2008 he explained, “Some people are born blind, or insane, or have a dormant brain but have healthy bodies. We don’t need to establish clones. We can use these people to transfer your brain into their body. I saw a show on television where a grandfather who was an engineer invented a way to cure his grandson of a malady. So, I know it can be done. I have patented a procedure for transferring memory from one brain to another by a kind of reverse x-ray machine.”  When I asked him how this invention related to his art, he lectured me, “Let’s get one thing straight. I don’t consider myself an artist. I consider myself a sign painter. I’m not interested in me. I’m interested in what we can do to help somebody else. I know this is a helluva conversation, but I’ve been working at it since I was a kid…since I saw that cicada. I feel like I’ve been programmed by God to be the only one to see the miracle of the cicada. It’s been on my mind since I was seven. The only intent I have in living is passing something on to the next generation. I want the world to know you don’t have to die. That’s more important to me even than my paintings.” Ed was not done, however. He had an important qualifier about his project to add. “I just want my brain to be transferred into the body of a 17-year-old before I turn 89. But it has to be the body of a white man because I don’t want to go through another lifetime of all that discrimination again as a black man. I want to come back as white but with my own black brain.”

When I asked him how this invention related to his art, he lectured me, “Let’s get one thing straight. I don’t consider myself an artist. I consider myself a sign painter. I’m not interested in me. I’m interested in what we can do to help somebody else. I know this is a helluva conversation, but I’ve been working at it since I was a kid…since I saw that cicada. I feel like I’ve been programmed by God to be the only one to see the miracle of the cicada. It’s been on my mind since I was seven. The only intent I have in living is passing something on to the next generation. I want the world to know you don’t have to die. That’s more important to me even than my paintings.” Ed was not done, however. He had an important qualifier about his project to add. “I just want my brain to be transferred into the body of a 17-year-old before I turn 89. But it has to be the body of a white man because I don’t want to go through another lifetime of all that discrimination again as a black man. I want to come back as white but with my own black brain.”

— Peter Hastings Falk