Documentary Film

A team of Finnish filmmakers, Janna Kyllastinen and Kati Aho, are working on a full-length documentary film. You are invited to view their poignant 6-minute trailer here.

Editorial Note

Since Iria’s death in 2022, her estate collection has been overseen by the Iria Leino Trust set up by Sir Robert Alan Saasto, an attorney well known in the Finnish American community. Saasto began by generating a groundswell of interest from Finns, including Jarmo Sareva, the Consul General of Finland and Kati Laakso, Executor Director of the Finnish Cultural Institute, also in New York. Saasto hired art historian and independent curator Peter Hastings Falk to manage this rediscovery project. Having sorted and archived her numerous journals, letters, photographs, and studio notes, he offers this introductory essay to begin an understanding of Iria. Plus, Iria’s large collection of paintings, stored away like a time capsule, have been expertly photographed by Terence Falk. We continue our immersion in a large body of archival materials — and translating from Finnish, Swedish, and French — a long process kindly begun by Jaana Sareva. Varpu Sihvonen, a reporter from Finland, who personally knew Iria for many years, is writing a book about Iria’s personal life and struggles. The present essay focuses largely upon Iria’s career in Paris and rebirth as an artist in New York, but her childhood is a sad and complicated story briefly explained in the last footnote of this essay (footnote #22).

Exhibition: September 2024

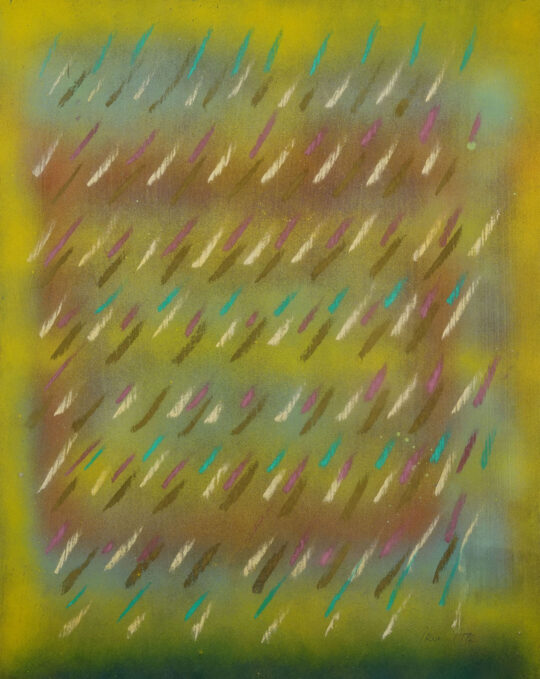

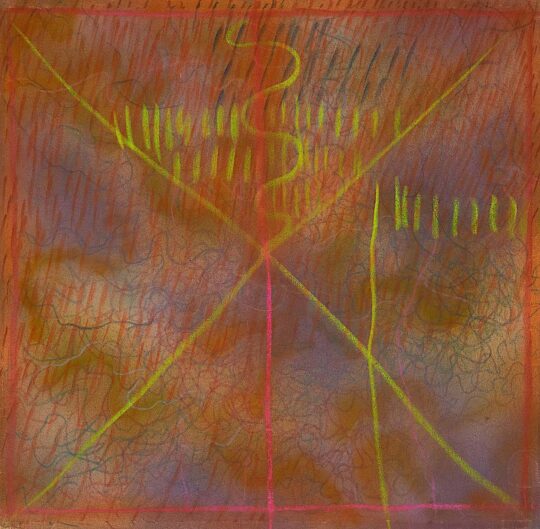

On September 5, 2024, Harper’s Gallery in Chelsea is opening a rediscovery exhibition at their gallery located at 512 West 22 Street in New York City. This exhibition focuses on Iria’s innovative Color Field Series and her Buddhist Rain Series from the 1960s.

Introduction

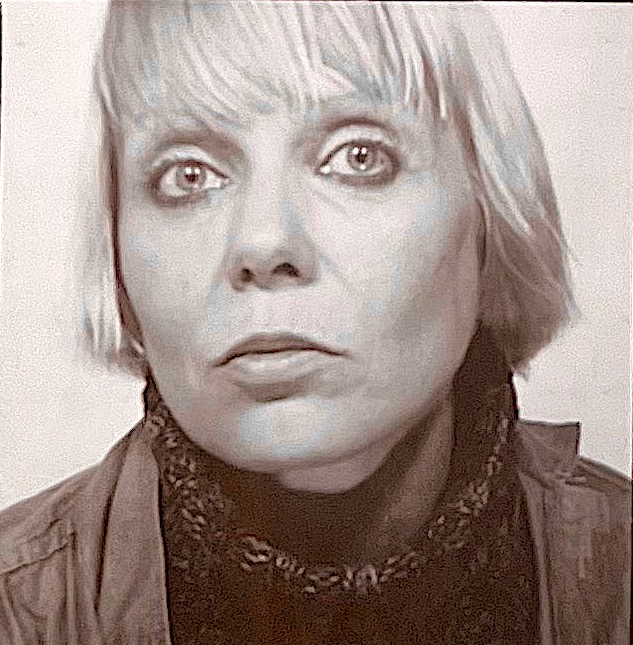

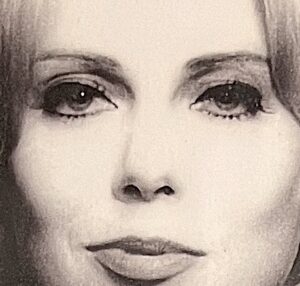

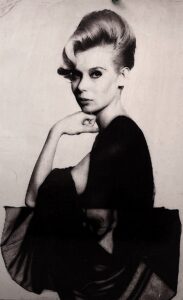

It’s Paris, 1955. Shortly following the end of World War II, Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists had won worldwide publicity that had turned New York into the new capital of the art world. For the flourishing fashion world, this was of little consequence because Paris remained its capital. In the art world, the city still cast a powerful spell upon numerous students from around the globe who felt compelled to make the pilgrimage to Paris to study at its art academies. One of those students, a beautiful young Finnish woman, was studying at the École des Beaux-Arts when she was discovered by the leading haute couture fashion houses. She was lured away and soon became the supermodel known as “IRIA” — walking the fashion runways of Europe for the leading couturiers. However, after eight years of the high life, she paid a price for her role in defining a new era of Parisian glamour. She felt the weight of being objectified as an expression of female sexuality and was losing the sense of her true self. She also suffered from anorexia and bulimia. In 1964, just as she reached her peak in modeling, she bravely broke away from the career that had made her famous. Her escape to New York meant returning to her original mission to focus on a life of painting, eventually settling into a 4,000-square-foot loft in SoHo. She never shook her eating disorders, but her embrace of a new spiritual life in Buddhism calmed her. She also became increasing reclusive and ascetic. After some early frustrations with art dealers, she shunned them altogether. Her studio became her world, and she became a prolific innovator of abstraction. Upon her passing in 2022, her studio had become a virtual time capsule preserving five decades of painting.

It’s Paris, 1955. Shortly following the end of World War II, Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists had won worldwide publicity that had turned New York into the new capital of the art world. For the flourishing fashion world, this was of little consequence because Paris remained its capital. In the art world, the city still cast a powerful spell upon numerous students from around the globe who felt compelled to make the pilgrimage to Paris to study at its art academies. One of those students, a beautiful young Finnish woman, was studying at the École des Beaux-Arts when she was discovered by the leading haute couture fashion houses. She was lured away and soon became the supermodel known as “IRIA” — walking the fashion runways of Europe for the leading couturiers. However, after eight years of the high life, she paid a price for her role in defining a new era of Parisian glamour. She felt the weight of being objectified as an expression of female sexuality and was losing the sense of her true self. She also suffered from anorexia and bulimia. In 1964, just as she reached her peak in modeling, she bravely broke away from the career that had made her famous. Her escape to New York meant returning to her original mission to focus on a life of painting, eventually settling into a 4,000-square-foot loft in SoHo. She never shook her eating disorders, but her embrace of a new spiritual life in Buddhism calmed her. She also became increasing reclusive and ascetic. After some early frustrations with art dealers, she shunned them altogether. Her studio became her world, and she became a prolific innovator of abstraction. Upon her passing in 2022, her studio had become a virtual time capsule preserving five decades of painting.

From Helsinki to Paris

Th woman who would become known by a single name — IRIA — was born Taiteilija Irja Leino in Helsinki on December 22, 1932. Sadly, her mother died when she was only six. She was raised by “Aunt Venny” — a woman she sometimes referred to as her foster mother. From ages ten through eighteen Iria studied at the Swedish Girls’ School in Helsinki before entering Helsinki’s Academy of Fine Arts in 1951. On her path to becoming a cosmopolitan artist, she spent the summer of 1952 working and painting in Stockholm, followed by the summer of 1953 in Copenhagen. She earned her degree is fashion design in 1955 and was named Best in Class, yet she was attracted by the possibilities of careers in both fashion and art. One of her instructors, Tapio Wirkkala [1915–1985], a leading post war Finnish designer and sculptor, wrote her a recommendation letter to study painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. She spent two years studying there under Raymond Legeult [1898–1971], a colorist of the first-generation School of Paris painters who was inspired by the figurativism of Bonnard and Vuillard. She also studied privately under the modernist André Lhote [1885–1962], who founded his eponymous school in Montparnasse in 1922. During her two years of studio practice, she also became a fashion correspondent for Finnish newspapers and magazines, reporting on the latest fashion trends emerging from Paris. This role naturally brought her into contact with the major fashion houses.

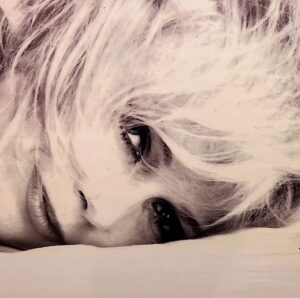

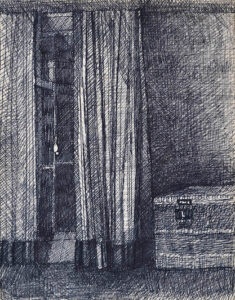

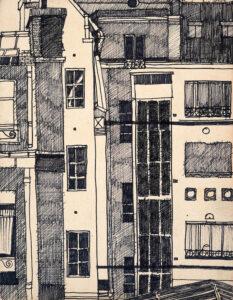

In 1958, an interviewer for a Finnish magazine learned that the French admired her not only as a model but also as a fashion designer because her drawings had clean lines and omitted excessive decorative details. Iria then announced that Vogue was featuring a hat she had drawn for its next issue. She proudly added, “I never asked for help from anyone and did not get any help. I always had to start from the beginning, alone and with my own strength. It has only been good for me. I have been the loneliest person in the world. Earlier that felt very harsh, but now my life has started to open up.”3 It proved to be a luxurious explosion. In 1959, her distinctive hairdo known as nouvelle vague (“new wave”) became the rage for the women of Paris. The next year, she could afford to purchase an apartment at 10 rue de Quatre Vents in the Latin Quarter. She enjoyed a roof-top view apartment on the 5th floor whose only furniture was a big bed and a travel trunk. An easel sat in the center of the living room waiting for her return from Europe’s major cities. She later purchased a farmhouse in Taormina, Sicily — a favorite getaway for summers she called “Paradie Rouge.” But in the summer of 1961, the death of the woman she considered her mother, “Aunt Venny,” left her depressed. Iria quickly left a photoshoot in Switzerland to arrange the funeral in Helsinki. She later walked alone deep into the verdant forest, experiencing its colors and smells while deeply questioning if the stress of her career was worth it. “I feel emptiness around me. Right now, nature is still colorful and beautiful,” she remarked during an interview. “I am like a wounded animal, seeking comfort from nature. I listen to the whispers and sighs of the trees. I want to remove the mask of modeling and let the rain drops fall on my face. I want to settle accounts with myself, with life and death. They called me an orphan when I lost both of my parents. I assume I didn’t quite know what they meant. Now, I really feel like an orphan.”4

In 1958, an interviewer for a Finnish magazine learned that the French admired her not only as a model but also as a fashion designer because her drawings had clean lines and omitted excessive decorative details. Iria then announced that Vogue was featuring a hat she had drawn for its next issue. She proudly added, “I never asked for help from anyone and did not get any help. I always had to start from the beginning, alone and with my own strength. It has only been good for me. I have been the loneliest person in the world. Earlier that felt very harsh, but now my life has started to open up.”3 It proved to be a luxurious explosion. In 1959, her distinctive hairdo known as nouvelle vague (“new wave”) became the rage for the women of Paris. The next year, she could afford to purchase an apartment at 10 rue de Quatre Vents in the Latin Quarter. She enjoyed a roof-top view apartment on the 5th floor whose only furniture was a big bed and a travel trunk. An easel sat in the center of the living room waiting for her return from Europe’s major cities. She later purchased a farmhouse in Taormina, Sicily — a favorite getaway for summers she called “Paradie Rouge.” But in the summer of 1961, the death of the woman she considered her mother, “Aunt Venny,” left her depressed. Iria quickly left a photoshoot in Switzerland to arrange the funeral in Helsinki. She later walked alone deep into the verdant forest, experiencing its colors and smells while deeply questioning if the stress of her career was worth it. “I feel emptiness around me. Right now, nature is still colorful and beautiful,” she remarked during an interview. “I am like a wounded animal, seeking comfort from nature. I listen to the whispers and sighs of the trees. I want to remove the mask of modeling and let the rain drops fall on my face. I want to settle accounts with myself, with life and death. They called me an orphan when I lost both of my parents. I assume I didn’t quite know what they meant. Now, I really feel like an orphan.”4

Escape to New York

Iria would hold on to her two European properties for the rest of her life, but in Spring of 1964 she found a timely escape plan when she secured a student visa and represented Finland at the 1st World Congress of Handicraft held at Columbia University. Iria had probably heard that the city’s approximately 20,000 Finns had been centered in the Sunset Park neighborhood in Brooklyn since the early 1900s. But by the time she arrived in 1964, even though Finnish could still be heard on the streets of the Brooklyn neighborhood, the youth were making a steady exodus.5 In early June, she sublet an apartment on the Upper East Side. She struggled to make ends meet because her total financial worth was tied up in two properties that she refused sell, with her only source of revenue being the money yielded by her Paris apartment lease. Fortunately, her personality was ingrained with a very Finnish type of stoicism for facing adversity — sisu — or grit. Working out of her apartment, she began her first venture, designing fabrics for the Finnish design house, Marimekko.6

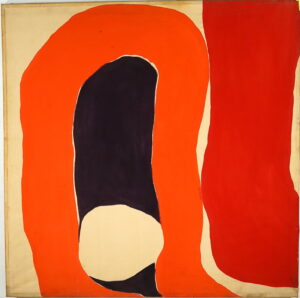

In 1965, Iria’s repossession of her life in art began in earnest when she entered the Art Students League. During her first three years she produced an extensive body of abstract canvases that boldly present her own response to the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. Many express the adventurous shapes and bold colors one might even suspect could be employed in Marimekko’s fabric design. Luckily, during this period her tuition and art supplies were covered by scholarships from Art Students League, two Ford Foundation grants, and one from Anco Wood Foundation. Her first influential teacher in 1965 was Sydney Gross, followed by Larry Poons from 1966 to 1970. In 1966 she discovered the ideal (and cheapest) studio space in a long-abandoned raw loft space on Greene Street in SoHo, having been made available owing to the gradual withdrawal of its factories and sweatshops. Only a print shop and two seamstresses kept their businesses in her building.

Word had spread among artists that SoHo’s 19th century buildings sported spacious factory floors with tall ceilings. Despite being a rough-and-tumble neighborhood, many artists — ignoring the city zoning ordinance against residential use — considered it a haven. Iria was part of a movement of women from the second generation of abstract painters who emerged during the late 1950s to mid–1960s. Most were not socially connected but instead spiritually unified by an undefined zeitgeist reflected as bold expressions in their art. Iria’s approach to abstraction, like that of her peers, was not to slavishly regurgitate the past non-objective explosions of male angst of the New York School. Instead, they were invitations to discover lyrical themes with subtle vocabularies alluding to landscape, figure, and objects. Helen Frankenthaler [1928–2011], a peer who emerged during the 1960s to earn a prominent place in the pantheon of Color Field painters, often used titles as homage to the landscapes that inspired her, such as Head of the Meadow, Yellow Canyon, and Lake Placid. Spacious studios meant larger paintings. By 1966, Iria was deeply probing the Color Field movement. She saturated large raw canvases with poured or sprayed color but her staining technique was varied and complicated. She sometimes positioned paint cans and other objects on the unprimed canvas as it lay flat on the studio floor, thereby blocking the pigments and allowing the ghost shapes to remain. Subtle lines sometimes betray the use of a brush, and she might continue with sprays and splatters. Many of these paintings are optical forays into dreamlike worlds, often looking like aerial views, biomorphic forms, or explorations of the cosmos. However, Iria’s transition to SoHo was accompanied by a high anxiety over her failure to generate any income, and she was often late on her rent. She tried to cure her inner turmoil by turning to dexamyl, ostensibly a medication for weight loss and depression. Known as “purple hearts” and widely used as a recreational drug in the youth subculture, one of its side effects was anorexia.

The first bit of good news came at the end of 1966 when the Panoras Gallery at 62 West 56th Street mounted the first solo exhibition of Iria’s colorfully expressive abstractions. This was the same gallery that had given Donald Judd his first solo, in 1957. A journalist interviewing her expressed his curiosity about why she had chosen a life of asceticism as a painter in SoHo considering it was such an abrupt change from having been a famous fashion model of the Parisian haute monde. Her response was candid: “I am happy to have known the ‘high’ life, the best parties and all that, but now I just want to work at expressing myself. The modelling world was glamorous, yes, and — well, being beautiful is a problem. But it was the kind of problem that turned life inside-out and left me feeling ugly because it had almost nothing to do with me. I was tired of surfaces.” When asked about her working process, she replied, “Painting is liberation for me. I think about the composition but then my emotions pour out into the actual painting without further thought.” Her dedication was so weighted that she added, “I may never even marry, for I feel I’m wed to my art.” Her future plans were simply “To get away from people, yet near people. I need tranquility; otherwise, there is nothing. I want to own as little as possible. My paintings are getting so large there’s hardly room for anything else!” 7 The concept of a glamourous supermodel model who turned in her haute couture dresses for paint-stained blue jeans and t-shirts caught media attention, and a few months later she appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson along with the Swedish actress Ingrid Thulin.

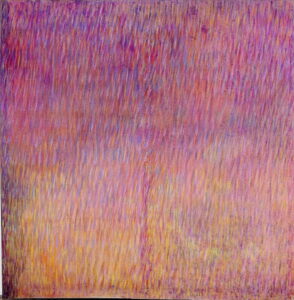

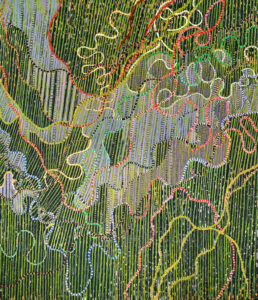

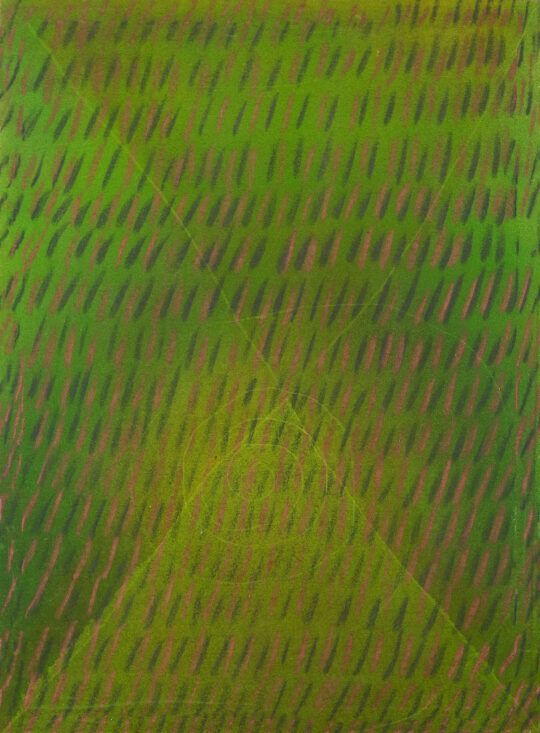

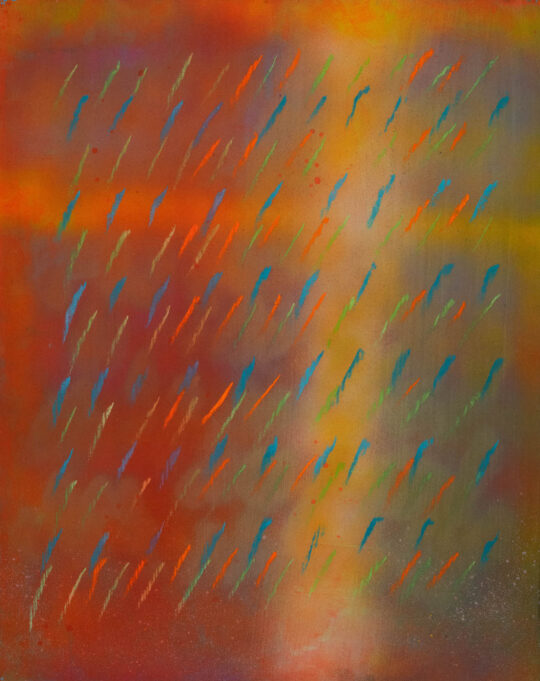

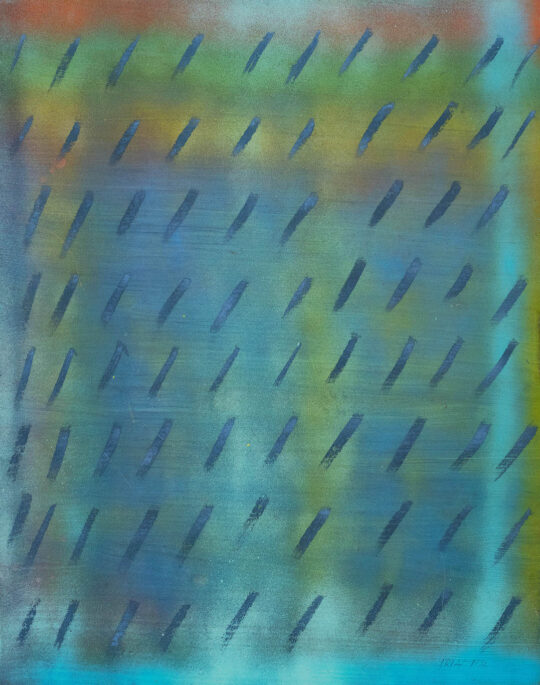

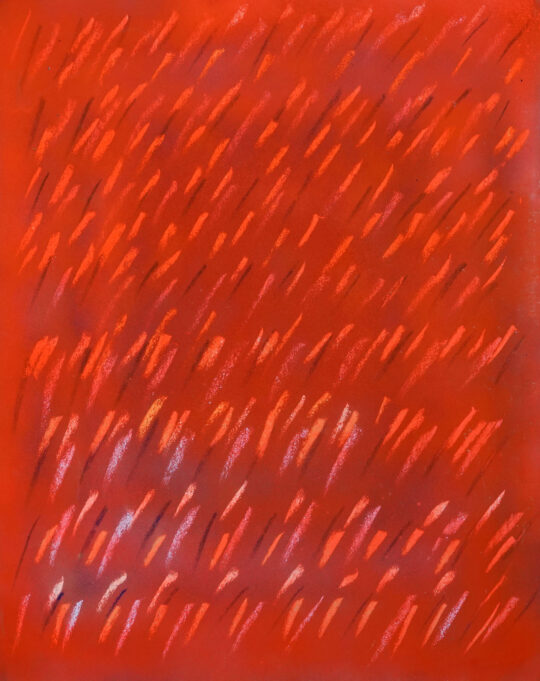

What seemed a propitious start turned into a setback in 1968 when Iria’s skull was fractured by a bottle thrown off a roof. She was rushed to a hospital. The injury was so severe that surgeons inserted a steel metal plate to close the skull. During the two-week recovery in the hospital, she had a dream that gave her the answer she had been seeking. “I saw the vision of a painting in green colors with three shining halos, and I heard a voice declaiming: ‘You shall be a painter!’”8 Her physical recovery was soon after followed by a spiritual recovery when she converted to Buddhism. She came to manage her anxiety without drugs and found a new impetus for her painting. Her Elephant Series of 1968 is a sequence exploring a sacred animal associated with Buddhism. The elephant represents the enlightenment and reincarnations of Buddha. The legs and trunks of the elephant are elegantly implied by their undulating shapes, and their solid fields of curving color with crisp edges appear to have been applied with a squeegee. Some of these homages to the elephant occasionally interject subtle use of the brush. For one full year, Iria focused on developing a karmic relationship with the elephant, a soulmate imparting wisdom and physical and mental strength. This ushered in her ongoing practice of painting as meditation, performed with classical music. The meditative approach continued with her next major series — the Buddhist Rain Series (1968–1972). After creating the color field base, she overlaid it with thousands of diagonal strokes in horizontal rows, suggesting a driving rain. For the first time, she also painted this new series on paper, including in pastels. Richly innovative and delicate, this was a progression that continued over four decades.

“When I had my Buddhist time, I had a Buddhist hymn ringing in my ears constantly, which I then painted onto the canvas. I had a Hindu mantra that had been given to me, but you were not supposed to stay it aloud. So, I repeated that in my paintings. Then came the visual side and now I only see the art.”8

Iria remained resolutely immersed in her artistic quest but many of the journals, diaries, and letters — in which she frequently switched between Finnish, French, English, and Swedish — show that she also remained afflicted by her eating disorders. She was compelled to keep detailed records of the exact time she consumed each food type and every calorie throughout the day. In 1971 she found a harmonious key with Buddhism when she began following the spiritual therapies of a prominent yogi — Sri Swami Satchidananda — who she affectionately called “Gurudev.” She was aware that artist Peter Max had been profoundly affected by the Yoga master when he met him in Paris in 1966. Max urged him to come to New York and helped him to establish the Integral Yoga Institute. “The Swami and yoga taught me a whole new way to draw,” said Max. “It empowered me to feel the cosmic consciousness within, and to allow that to flow out of me into my art.” 9 When the Woodstock Festival opened in the summer of 1969, Gurudev was lowered onto the stage by a helicopter, and in flowing orange robes delivered the opening address to the huge crowd.

Gurudev’s dynamic spiritual presence also had a profound and lasting effect on Iria. She credited him with healing her bulimia. Moreover, he fulfilled his assurance that her uncompromising focus on the act of painting was also an active form of meditation. She would, like Peter Max, tap a cosmic consciousness that would result in truly innovative imagery. However, during her devout following of Gurudev’s dharma she also became increasingly reclusive. Painting became such a private world that she no longer felt the pressing need to divert her energies into pursuing the often-demeaning process of supplicating art dealers to exhibit her work. Indeed, throughout her life very few people were invited into her loft. She admitted, “I have had the need to concentrate and be alone. I have had difficulties getting along with people and perhaps I have isolated myself even too much.”10 Among her few visitors were Matti Sallinen, Finland’s greatest operatic bass, and Martti Ahtisaarie, who would become President of Finland in 1994. “Martti Ahtisaarie, our representative at the UN, and I went to the studio of the famous artist Iria Leino in SoHo. Iria lives on the sixth floor of an old factory without an elevator. Endless stairs painted blue start from the front door, surrealistically leading directly into the sky. God bless you. But isn’t it true that there is always something to suffer for the sake of art?”11

Iria did become part of crowds when she was a political activist. Deeper research into her journals will reveal the extent of her participation in public demonstrations supporting the Women’s Liberation movement led by the National Organization for Women (NOW), formed in 1966. In 1968, nationwide news covered the protest of The Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey, when women filled a “Freedom Trash Can” (later mythologized as “bra-burners”). In New York, Iria protested discrimination in the art world over the chronically pathetic lack of representation of women in museums and galleries. One souvenir that she kept in her loft was a large American flag mounted upside-down on a pole that she waved at these protests. In 1972, a journalist for a Finnish magazine interviewing Iria wrote, “She belongs to a Women’s Liberation art group that includes painters, sculptors, writers, and movie makers, which meets weekly and sometimes protests before the Metropolitan Museum and the Whitney to promote the exhibition of female artists.”12 It is not known whether Iria was one of the anonymous members of the later feminist collective called the Guerilla Girls (founded in 1985) whose members wore gorilla masks to hide their identities.

When it came to the opposite sex, Iria the supermodel was a feminist with no shortage of boyfriends. Yet every one of them who proposed marriage to her — from Paris to Sicily to San Juan to Rio — had to accept a firm rejection. As one who had been exhibited on runways and in magazines as a sexual object, her relationships with men were marked by a role reversal. It was she who carried a reductive view of sexuality and persisted in claiming a right to her own body and sexuality. Despite characterization of the Woodstock Festival of 1969 as the harbinger of a generation promoting a “free love” counterculture, many women still found it hard to conceive of economic survival outside of marriage. Yet, Iria, despite her chronic lack of money, always saw marriage as an anchor that would only impede her creative quest. This instinctive philosophy prevailed throughout her life, even though it was her habit to record her lovers in her journals and save their love letters. One example was an affair that began with the abstract painter Stanley Boxer, which began in the early 1970s and lasted for years. When Boxer’s irate wife discovered the affair, she vowed to destroy Iria’s future for exhibiting in New York. Boxer was one in a long succession of men in Iria’s life who failed to realize that she would never commit to marriage. She had no desire to pour emotional labor into supporting a husband when that energy was reserved exclusively for her making art. She called her paintings her children — and Gurudev’s teachings of spiritual consciousness kept reconfirming her mission.

An Outpouring of Lyrical Expressionism

After 1969, and for the next fifteen years, there would be no signs of Iria returning to a brush. This partly explains why, after her death, no brushes could be found in her studio — only an assortment of trowels, scrapers, and squeegees. One of her large canvases from this period was purchased by Larry Aldrich and in 1973 exhibited in “Contemporary Reflections” at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art. Also in 1973, one of her large paintings was chosen for the exhibition, “Women Choose Women’s Painting and Sculpture,” at the New York Cultural Center. In the introduction of the catalogue, art critic Lucy Lippard offered the cultural reminder that “New York Museums have been particularly discriminatory, usually under the guise of being discriminating.” James Mellow’s review in the New York Times selected only three women whose abstractions were outstanding: “Alice Baber’s delicate veils of color, Carmen Herrera’s incisive geometry in Cobalto Blanco, and Iria’s handsomely tapestried Wish Answered.”13

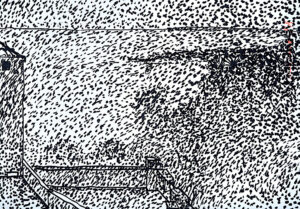

In 1974, Iria made her most decisive move away from the controlled soaking and staining of diluted acrylics into the canvas fibers — the hallmark technique of the leading Color Field painters of the late 1950s–60s: Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Paul Jenkins. Iria instead purchased raw powder pigments and mixed them with an acrylic emulsion (originally branded as Rhoplex). Then, by adding water, she created a viscosity with which she could control the velocity of her pouring of thin layers on top the canvas fabric, not absorbing into it. The paint was now heavier and held greater opacity as it flowed in narrow irregular stripes down the canvas surface. These were distinguished by decidedly vertical streaks energized by the color scheme, the whole typically finished by carefully controlled splattering. She called these paintings simply The Flat Series — representing her enduring quest to express the merging of the natural world with the spiritual world. A primary source of her inspiration was the beauty of Finland’s forests and rugged coastline. Iria made occasional trips back to Finland and many times wrote that she longed to buy an old schoolhouse deep in the country and spend the summers there painting. Finnish culture had imbued in her a deep appreciation of nature, largely aroused by its unusual topography. The great majority of the country is forested, laced by hundreds of rivers, with the whole carpeted by thousands of lakes. Even the Finnish name for the country, Suomi, is derived from the word for bog. Her titles sometimes specifically reflect her nostalgia for the Finnish landscape, such as Finnish Spring Forest (below). Certainly, Iria was aware of the Finnish master of the lyrical expressionist landscape, Akseli Gallen-Kallela [1865–1931], and the hidden spiritual meanings of his canvases did not escape her. 14

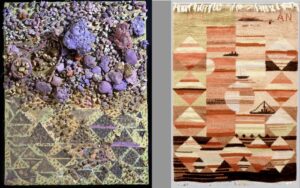

Further evidence that Iria’s unique approach to abstraction was grounded in her Finnish artistic roots is seen in an exceptional wall hanging she created in the late 1970s — called a ryijy. Literally translated as rug, the ryijy [pronounced ree-eh] is made of a long-tufted thick pile woven with plant-based yarns and dyed in natural colors. This rug-as-art form was unique to Finland and it continues to be popular to hang them as tapestries in Finnish homes. By the early 20th century, the country’s artists and textile designers were creating modernist ryijys. Iria’s chose the Buddhist Rain Series to represent her ryijy (below). Produced in a limited edition, its upper band of blue merges at the center with red, thereby becoming a central band of purple, and the color scheme flows to the bottom half as a band of red. The whole is marked by four rows of red slashes of driving rain — the stylistic theme of her series of paintings. One of her aspirations was to return to Finland with an exhibition of her ryijys in earthy colors. Coincidentally, it was during the 1970s when American rug manufacturers discovered the popularity of the Finn’s long thick-piled ryijy rugs and copied the concept. However, they instead produced what became the trendy shag carpet of the period.15

Breaking Out: Painting–Sculpture

“Color is my language. My paintings are all very different but there is a unifying thread. I have changed a lot, both in method, as well as in material and colors. Right now, colors are subdued and bright (as me). I like the light in my atelier — on the other hand, when I am there, I don’t remember where I am. I change over the seasons, and I have learned to simplify my life and my relationships — I have become cleaner. I no longer waste time; I eliminate everything that’s unnecessary.” 16

Toward the end of 1976 Iria made a significant transformative step in the evolution of her Flat Series. She always thought of these as rugs (ryijys) rugs, and she now mixed her pigments in thicker heavier layers that she carefully manipulated to suggest topographic forms. These works were facilitated by her adoption of three old German metal hand-cranked stucco machines. House painters used these to apply their mixture of drywall stucco made of sand and water. Iria’s bas-relief works look like aerial views of canyons and rivers of rich colors, or vibrant lava flows on a planet pocked with craters from asteroid hits. In 1977, the Director of the Amos Rex Museum in Helsinki — who called Iria “the calmest artist I have ever met,”12 was so impressed by the authenticity inherent in her natural abstractions that she was given a solo exhibition featuring thirty-nine paintings selected from The Flat Series as well as her latest large bas reliefs. Three large works were also later exhibited at the spacious Liljevals Museum of Art in Stockholm (Liljevalchs Konsthall). Immediately after these exhibitions, Iria flew to India to meet Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh [1931–1990], a charismatic yet controversial spiritual leader at his ashram in Pune, just east of Mumbai. His form of dynamic meditation — which combined music, dance, and even shrieking before culminating in silent meditation — was attracting many Western followers.17

Not long after to returning to New York, Iria realized that the risk of eviction from her loft had greatly increased. By the late 1970s, the gradual influx of galleries to SoHo that had begun earlier in the decade had greatly expanded. The path to gentrification was unstoppable and the old factory buildings were quickly being converted to co-ops with posh apartments. Artists were at risk despite being protected by the “Artist-in-Residence Law” that had been passed in 1973. In 1978, Iria’s building on Greene Street went co-op, and she was forced to fight a series of legal battles to retain the status of her rent-stabilized loft. In part to strengthen her case, she became a U.S. citizen. Nevertheless, her legal battles carried on for decades, and the constant fear of eviction and loss of her art is why she never considered returning to Finland for longer periods. She ultimately won and held the unrestored loft for the rest of her life.

By 1981, Iria’s experiments that had begun as bas-relief had been driven toward far greater topographic height. She developed a haute-relief that is a form of wall sculpture. The largest of these is The King’s Krone (Crown) at eight feet tall (above) — an extraordinary conglomeration of thousands of rocks and pebbles. Half are painted white, and the rest reveal a variety of colors. Each was then embedded by hand in a thick polymer base. The whole image is laced by nine subtle and roughly equidistant horizontal bands of light blue. In many of the topographic works, Iria continued to control the heavy sandy polymer mud with her hands, creating ridges of sand snaking their way vertically, often to heights up to eight feet. She often later embedded aquarium gravel and even dried peas in the pigment. She created furrows by gouging and pulling the mud with her fingers, exposing layers of color in streaking patterns. Her highest peaks were achieved in Homecoming (After) of 1982 (96 x 33.5 inches) with its vertical path of two pairs of red women’s shoes rising amongst three scattered whisky bottles.

Beginning in 1983, Iria created what became an extensive body of smaller painting-sculptures she simply called The Squares Series (above). Ranging in size from 5 x 5 to 12 x 12 inches, the thick polymer mud mixed with marble dust was embedded with a variety of objects, including found plastic and metal parts, electrical wires, metal tubing, screws, chunks of gravel, shells, colorful pebbles, and brick fragments. A large number are composed entirely of acrylic “skins.” These elements were created by first laying layers of acrylic paint on a smooth sheet of glass or metal surface, continuing the process until the layers had become very thick. When the sheet was dry, she scraped it off and broke it up into many small, rugged fragments. These acrylic “skins” became a distinctive element protruding from the canvas.18

While Iria continued her pursuit of three-dimensionality through 1989, she had also returned to using the brush in 1985. For the next seven years she developed the Growing Series, which is almost entirely focused on a single common houseplant called the Lucky Bamboo. Now in her fifties, Iria’s spiritual life had led her to discover and adopt more Far Eastern practices. Through Feng Shui cures she learned that the Lucky Bamboo would enhance the flow of positive energy as well as bring good luck and prosperity. She meditated before this plant every day and paid homage to it in an extensive series that also inspired her to create related biomorphic abstractions alluding to growth. It was as if she had become a transcendental botanist.

The name of Iria’s final series of large canvases was left untitled but this author could not help but name it The Dreamings Series. These were created from 1988–1989 and represent the culmination of her painting through meditation. In these canvases she employed curving colorful lines forming shapes within which are enclosed thousands of short strokes, dabs, and dots. Sometimes those animated strokes exist as clusters forming shapes without linear borders. All evoke the spiritual authenticity of the “dreamings” paintings of the Australian Aborigines. Even Iria’s titles seem fitting, such as Ant Path and Predation. Another title, Zanden, means one who is a self-reliant explorer and innovator — describing Iria herself.

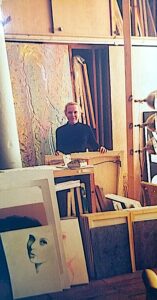

In 1988, Iria hired her first and only assistant, Corbin Frame, a young artist to help her prepare for a successful solo exhibition of more than forty paintings that would appear the next year in a new gallery that was opening in Helsinki called Artfaber. “Iria was strictly an ascetic, tied to her studio. The only hints that it was also her residence were her Alvar Alto chairs,” he recalled. “I never saw her when she was working. No person was ever allowed to watch her. And she became irate over interruptions. Except for her Yoga practice at the Institute, she was rarely around people. In her lifestyle she adhered to a philosophy of simplicity. Even when she spoke, she was simple, direct, and formal in manner, with very few words. And through meditation she coped with her eating disorders. Yet, her modeling years stayed with her. For example, whenever she ventured out, she dressed chic.” The only other exhibition in which Iria agreed to participate was the 4th Annual Loft Pioneer Show in 1999 (at age sixty-seven) because as one of SoHo’s founding loft artists it held a personal significance for her.

“Iria is like a stream, unreachable, unstable, unstoppable — changing and evaporating, looking for herself, looking for truth, following the path that is the salvation of her life — and its only purpose.”19

Iria preserved memories of the fame she achieved in Paris. Her archive includes large portfolios with numerous black & white photographs by leading photographers. Boxes containing the fashion magazines in which she appeared in full-page advertisements attest to her stardom. Just as she was discovered in Paris in 1957 for her beauty, her journals reveal her feeling that by the same good fortune she should have been discovered in New York for her art. With decades of large ambitious paintings having formed her legacy, the woman who resolutely refused to be an active self-promoter had another reason for revisiting those striking photographs of her youth. From 2000 to 2004, they inspired her to create a series of self-portraits called the Meerson Girl Series, based on a photograph of her by Harry Meerson [1910–1991], one of the important fashion photographers in mid 20th century Paris.20 His work appeared in many of the top fashion magazines as well as the magazine Photographie. Meerson edited Dora Maar’s fashion photographs, and Brassai was a regular visitor to his studio. Fashion photographers exert control over their models, not only as they orchestrate poses during the shooting itself but in the effect that the final alluring image perpetuates once widely publicized. Forty-three years later, Iria was flipping the table on Meerson, finally asserting control over one of his famous portraits of her. Now, she was the one transforming his image into her reality. In the process, she produced numerous self-portraits in this series, often revealing psychological insights. For example, Double Vision (above) shows her pointillist image looking both right and left, subtly superimposed over a portrait of Gurudev to whom she was devoted. Meerson Girl with Fourth Eye (below, left) brings to the portrait brushstrokes of yellow, blue, white, and green slashing diagonally across her face, her eye assuring the viewer that even the most influential photograph never succeeded in taking control over her life.

Higa (Sweat) (above, right) portrays Iria the Meerson Girl superimposed over a pointillist image of the New York underground avant-garde fashion designer Claude Sabbah. In 2000, Sabbah surprised Iria when he asked her if, at age 68, she would return to the catwalk wearing unique dresses of his design. Iria thrived on emerging from the studio to pursue the opportunity to be in the limelight again. “It was quite shocking to be back on the stage after all these years,” she remarked. “But my love to be the center of attention on the stage has not disappeared.”21 This was another example of how contradictions would inevitably reappear in her life, and she remained enigmatic to the end. Iria’s resolute desire to be isolated in the studio, supported by meditation and a spiritual guru, generated the environment she required to push each of her series of paintings to their maturity. Moreover, she was the first Finnish woman pioneer of abstract painting in America. In the process, she infused Finnish nature and design into every painting — making her body of work a uniquely vibrant cultural fusion of Finland and America, a legacy to be shared by both countries.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Footnotes

1 Madame Grès [1903–1993] was best known for her couture gowns, but in the 1950s also experimented with minimalist designs, such as those found in Japanese and Indian dress. Despite tragically losing she lost her fortune late in life, she found support from her friends and colleagues, including Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin, and Yves Saint Laurent. Like Iria, Pierre Balmain [1914–1982] also studied at the École des Beaux-Arts. During the post-war years in Paris he became known at the “king of French fashion,” winning celebrity clients such as Katharine Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich, Ava Gardner, and Brigitte Bardot. Balmain’s apprentice, Karl Lagerfeld [1933–2019], who spotted Iria in 1957, later moved on as a designer for Jean Patou, Fendi, and Chloé. Christian Dior [1905–1957] died the year Iria’s modeling career was launched but his successors perpetuated his creation of the voluptuous “New Look” in fashion. In the in the mid 1950s, Iria took note of the first big hit for Pierre Cardin [1922–2020] — his “bubble dress.” Like his colleagues, he also toned-down haute couture with his prêt-à-porter line (ready-to-wear”). He set another trend in the 1970s with his “Mod Chic” line.

2 Simone Micheline Bodin [1925–2015] is often cited as the first “supermodel” in the late 1940s–1950s, and became known by a single moniker, “Bettina.”

3 “Two Faces of a Model” (Helsinki: Mirror, Aug. 1961) [Liikepankkien Asiakaslehti (Helsinki: Kuvastin, Aug. 1961)]

4 “From Finnish Art Student to a Top Model in Paris” (Helsinki: New Pictorial, 17 Oct 1958) [“Suomalaisesta taideopiskelijasta pariisilaiseksi tähtimannekiiniksi” (Helsinki: Uusi Kuvalehti, 17 Oct 1958)]

5 Finnish immigrants had conceived of and built in Brooklyn the first non-profit co-op apartment buildings in the United States — registered in 2019 in the National Register of Historic Places. (Source: a talk on Finns in America given by Robert Saasto on November 4, 2019 at a luncheon for the Consul General, Ambassador Mika Koskinen, at his official residence in Manhattan.

6 While Iria was providing designs for shirts, skirts, and pillowcases to Marimekko in 1964, it appears that her first fabric design was not published until 1977 (Source: Form/Function magazine, Finland, Apr. 1988). Marimekko opened its first shop in New York in 1963, and the brand would soon become internationally famous. Two of its loyal adopters included Georgia O’Keeffe and Jackie Kennedy. The emerging youth counterculture also adopted Marimekko as a bohemian brand, attracted by its bold simple patterns of colorful stripes, ovals, and chevrons — as well as its asymmetrical expressive abstractions of flowers, melons, and strawberries. (Source: Lutyens, Dominic. “Marimekko: The Nordic Look that Defined Freedom and Joy,” BBC.com Culture, 11 Aug 2021)

7 Stokes, Clively. “An Artist’s Model World” (Manhattan East, 1966)

8 “From New York to Helsinki for a Solo Show” (Suomen Silta – Bridge of Finland, June 1989, p.26)

9 Quote is from the biography on PeterMax.com. Max produced many drawings and paintings of the guru, including two limited edition prints of him in the 1970s. Sri Swami Satchidananda [1914–2002] was one of the first Yoga masters to bring the classical Yoga to the West. He founded the Integral Yoga Institute in 1966 on the Upper West Side near Max. His popularity led to the opening of an ashram and teaching center in Greenwich Village in 1970. In 1986, he opened Yogaville in Buckingham, Virginia, known for its enormous and extraordinary lotus-shaped Light of Truth Universal Shrine. He received honors for his interfaith spiritual teachings by the United Nations and many organizations dedicated to world peace.

10 Moisio, Mikki. “The Strange World of Finnish Iria” (unidentified publication, c.1970)

11 Simola, Liisa. “A Simple Life Makes You Happy” (Monalisa No.8, 1972) [“Yksinkertainen elämä tekee onnelliseksi”]

12 von Hellens, Ilse. “Iria, A Lonely World Traveler” (Jaana, No.39, 23 Sept. 1975) [“Irja, yksinäinen maailmanmatkaaja”]

13 Mellow, James R. “Art: Focusing on Works by Women” (The New York Times, 14 Jan 1973, p.57)

14 Iria was among the adventurers who were drawn to Finland’s northernmost region of the Sámi people known as hunter-gatherers and herders of the reindeer, that long-standing icon in the country’s cultural identity. For more than half the year this region covered in many feet of snow, a stage illuminated by brilliant displays of the Northern Lights. The last glaciation further enhanced Finland’s rugged topography with approximately 95,000 islands, most of which are part of archipelagos and stretch across the Baltic Sea towards Sweden. The length of the coastline is astounding — nearly 200,000 miles. Compare this to the American state to which Finland is closest in size — New Mexico — whose total boundary length is 1,434 miles.

15 The Finnish ryijy are thick wool rugs that were originally worn widely by the Scandinavian Vikings for warmth on ocean voyages. By the 18th century The Finns were creating these rugs as true textile art with more colors and patterns and they became popular hanging as tapestries in Finnish homes. During the “Golden Age of Finnish Art” [1870–1920] the Finnish master painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela [1865–1931] produced modernist ryijys at the turn of the 19th century. Entering the 20th century, the leading women textile designers creating ryijys as works of modern art included Laila Karttunen [1895–1981] and Greta Skogster-Lehtinen [1900–1994], followed by Kirsti Ilvessalso [1920–2019]. Several of the leading Finnish companies specializing in weaving rugs and tapestries as fine art in limited editions included Suomen Käsityön Ystävät (Friends of Finnish Crafts), Aaltosen Mattokutomo Kiikka, and the Kiikan Kutomo Workshop.

16 Ibid., von Hellens

17 Katso Lehti, No.20, May 1977

18 In consideration of the widespread adoption of acrylic pigments by the mid 1960s, it seems predictable that artists would eventually experiment with its pliable qualities. Today this technique is known as “painting with skins” but during the early 1980s its earliest adopters, like Iria, were completely unknown to each other. Among these painters was Michael Gallagher [b.1945] who recently recalled to this author that his discovery of the technique happened in his Soho studio in 1979. “One day I was surprised to find that when cleaning up my studio floor some large splatters and blobs of dried paint released from the plastic film used as a drop cloth to protect my floor. I don’t know of anyone who was using the technique before me” (Author’s interview). Perhaps the best-known artists also using the technique at this time were Frank Owen [b.1939] who exhibited them at the Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York in 1979; and, a few years later Jack Whitten [b.1939] was working with skins. It appears that none of Iria’s pioneering peers were aware of each other, yet each also invented special tools for creating their skins. One is hard-pressed to find others from that era, but the technique of skins is well-known today and encouraged by the big manufacturers of acrylic pigments.

19 Lehti, P.S. “A Dream Job as a Sideline” (Suomen Kuvalehti, May 1977) [“Sivutoimena unelma-ammatti”]

20 Another noted photographer of Iria was Jean Clemmer [1926–2001]. Parallel with his role as a fashion photographer, Clemmer led the way in erotic photography in the 1960s. The first of his close collaborations with Salvador Dalí began in 1962, including fashion spreads for magazines. Clemmer’s book, Nus (1969) caused a scandal.

21 Sihvonen, Varpu. “A Vedette’s Comeback” (Pinta – Aamulehden Muotilehti, 5 Sept 2000)

22 Varpu Sihvonen’s research reveals that Iria’s mother, Signe, was married to Bernhard Leino but they were already living separately when she became pregnant. Iria’s biological father was Mauritz Michelsson. But Signe was never remarried. Instead, Michelsson and the Leinos thought it best to just let everyone think the baby was Bernhard’s — which is why Iria was born Leino. When Signe died of breast cancer, Michelsson asked his friend Vendla (“Venny”) Nordling to raise six-year-old Iria. Michelsson then married Tyyne but they had no children. He also provided for Iria for as long as she lived in Finland. When Tyyne died, Michelsson decided he wanted to legally adopt Iria. She agreed, but insisted on keeping her last name, Leino. She also had to agree to keep Leino as her last name.

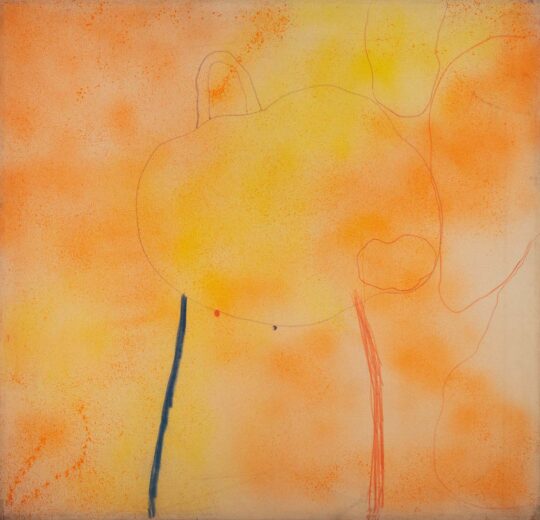

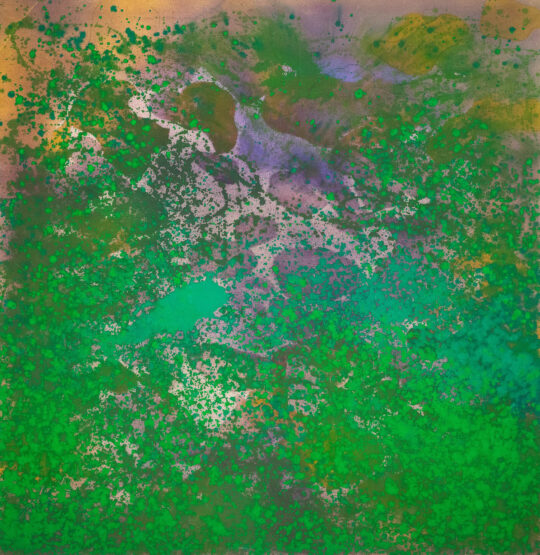

The Color Field Series (1967–69)

-

All Over, 1968

69 x 68.5 inches (175.26 x 173.99 cm) -

The Child, 1968

77 x 79 inches (195.58 x 200.66 cm) -

The Accident, 1969

79 x 77 inches (200.66 x 195.58 cm) -

Balloons #2, 1969

77 x 81 inches (195.58 x 205.74 cm) -

Started, 1969

66.25 x 68.3 inches (168.28 x 173.48 cm) -

More and More, 1969

78.5 x 76.5 inches (199.39 x 194.31 cm) -

No Beginning No End (#1), 1969

77 x 79.5 inches (195.58 x 201.93 cm) -

No Beginning No End (Sunset), 1969

75.5 x 79 inches (191.77 x 200.66 cm) -

This Very Moment, 1968

67 x 77 inches (170.18 x 195.58 cm) -

Eve’s Apple (Green), 1968

74 x 76.5 inches (187.96 x 194.31 cm) -

Eve’s Apple (Yellow), 1968

77.5 x 77.5 inches (196.85 x 196.85 cm) -

Arial Landscape, 1969

50 x 50 inches (127 x 127 cm) -

The World, 1967

77.5 x 77.5 inches (196.85 x 196.85 cm) -

No Beginning No End (Half Moon 2), 1969

76 x 79.5 inches (193.04 x 201.93 cm) -

Luscious Fruit, 1969

67 x 69 inches (170.18 x 175.26 cm) -

What You Want, 1969

79 x 76.3 inches (200.66 x 193.8 cm) -

Forms, 1968

77 x 81 inches (195.58 x 205.74 cm) -

The Back No.2, 1968

79 x 77 inches (200.66 x 195.58 cm)

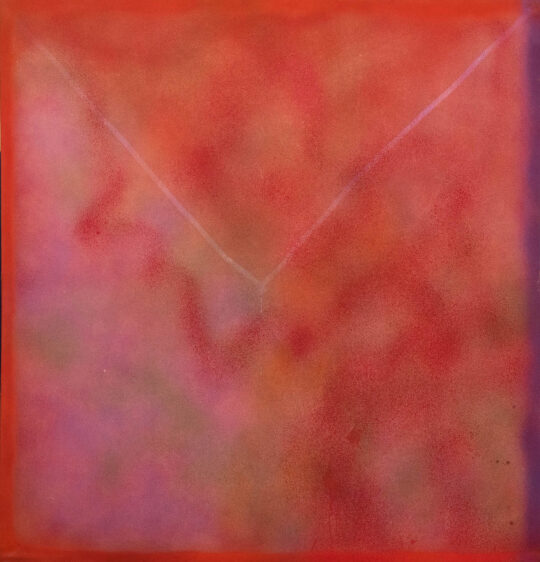

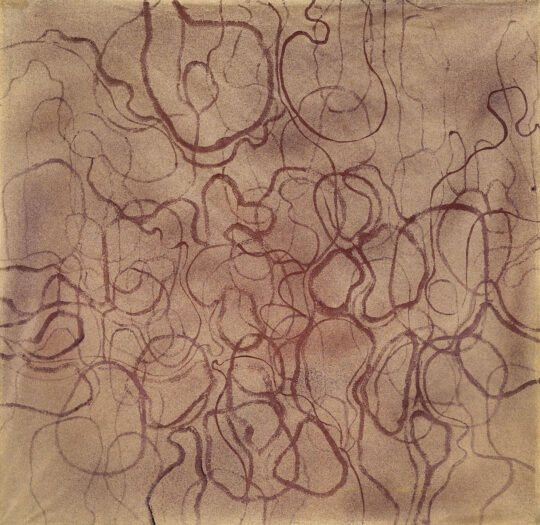

The Buddhist Rain Series (1968–72)

-

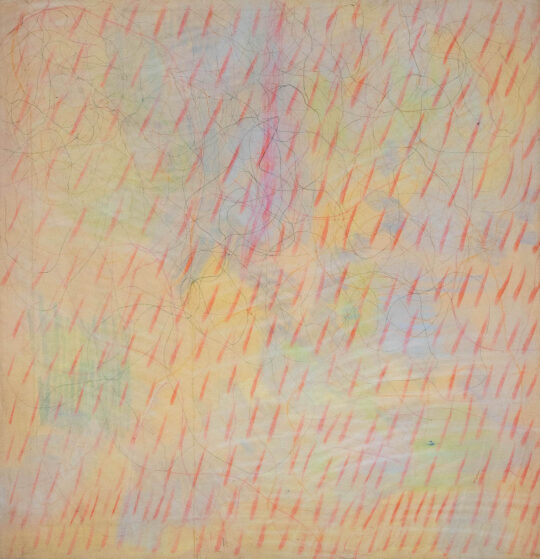

Always Changing, 1970

52 x 50 inches (132.08 x 127 cm) -

Explosive Thunder, 1970

53 x 50 inches (134.62 x 127 cm) -

Bud-Only Way, 1970

54 x 50 inches (137.16 x 127 cm) -

Les Roses Sont Les Roses, 1970

61 x 48 inches (154.94 x 121.92 cm) -

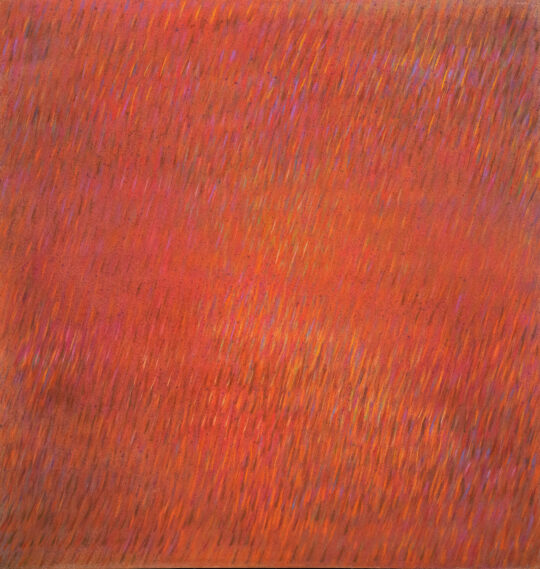

Life Saver, 1970

76.5 x 79 inches (194.31 x 200.66 cm) -

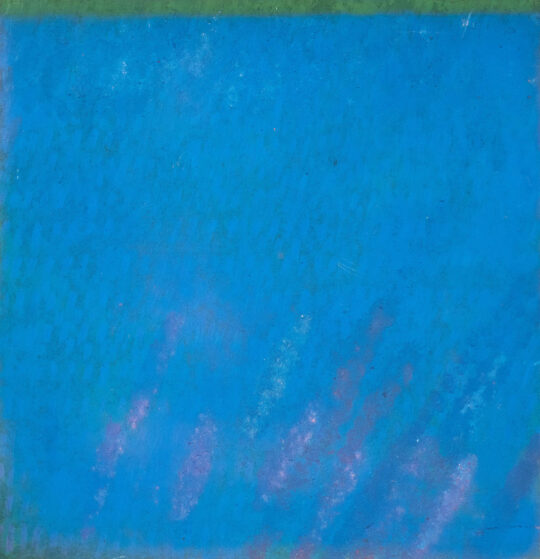

Mantra Blue, 1979

46 x 44 inches (116.84 x 111.76 cm) -

Heart, 1970

44 x 32 inches (111.76 x 81.28 cm) -

Future, 1970

85 x 31 inches (215.9 x 78.74 cm) -

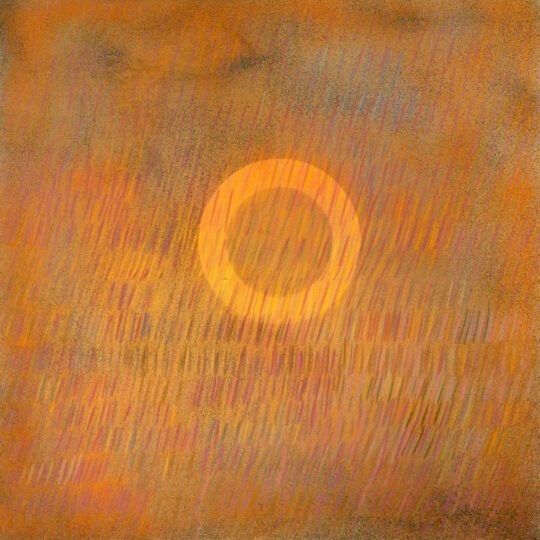

Sun Rain, 1968

49.5 x 50 inches (125.73 x 127 cm) -

The Tiny Seed, 1969

59 x 66 inches (149.86 x 167.64 cm) -

Mantra, 1971

72.5 x 48.5 inches (184.15 x 123.19 cm) -

Bud – At Least a Few Days, 1972

82.25 x 80.3 inches (208.92 x 203.96 cm) -

Falling Like Rain No.3, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Hudson Bay, 1975

70.75 x 76 inches (179.71 x 193.04 cm) -

Falling Like Rain, Nobody Around, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Falling Like Rain, the Fourth Stage, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Falling Like Rain, Here, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Falling Like Rain, Light, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Falling Like Rain, Centered, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Purple Rain, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

Falling Like Rain, Now, 1972

29 x 23 inches (73.66 x 58.42 cm) -

The Open Season, 1969

44.5 x 45 inches (113.03 x 114.3 cm) -

Guiding Angel, 1970

78 x 75 inches (198.12 x 190.5 cm) -

Off My Track, 1970

44.25 x 44.5 inches (112.4 x 113.03 cm)