The Immaculate Perception of Igor Gorsky

Igor Gorsky’s path to becoming an abstract expressionist painter is extraordinary and unique. For the first 52 years of his life, he was not an artist. He was instead a brilliant engineer and an economics theorist. He had also been a pioneering member of the think tank that created the Nasdaq securities exchange in 1971. Moreover, he wasn’t Russian as his name would suggest but Greek — born George Vassilopoulos in Athens in 1936.

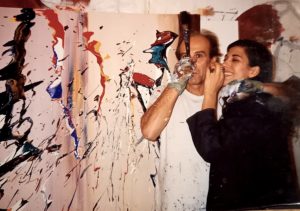

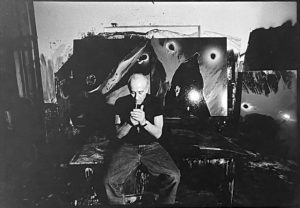

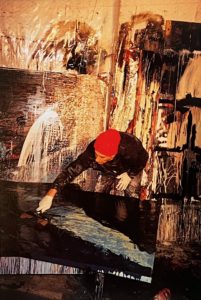

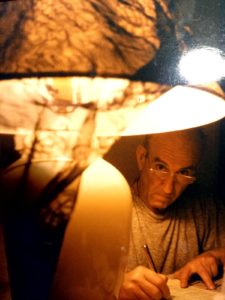

However, in 1988, at age 52, Vassilopoulos experienced an epiphany that completely transformed him into a painter. And it was no mid-life crisis. He had fallen in love with a deeply spiritual Greek artist, Evita Myriam, who was 29 years younger. She told him that she saw in him a huge fire of creativity and proclaimed that he had the potential to become a great artist. She gave him his first art supplies and was thereafter his muse and critic. Vassilopoulos was soon so obsessed with painting that he adopted the practice of working all night into the early morning hours, boldly splashing and pouring his chosen medium — car enamel — onto the canvas until he achieved the visual effects for which he was striving. “He moved like a ballet dancer, like Nureyev,” recalled Evita, “whom he had met when he was very young.”

Eventually, friends commented on the boldly expressive paintings that were hanging in his apartment and asked who created them. Still somewhat insecure because he was a guileless new artist with no training, he contrived the story that the paintings were not his but those of a Russian painter he had met by the name of Igor Gorsky. Also, being new to the game, he felt an assumed name would assure he received honest feedback instead of honeyed words. The source of this Russian brush name was Evita, who had described to him a dream she had about a man in a monastery who lived with a viscous wolf he had tamed. Later, she realized that her dream had summoned the Wolf of Gubbio that St. Francis of Assisi had tamed. But when she woke up from the dream and tried to recall the name of a wolf from a Dostoyevsky novel — likely because both she and Vassilopoulos were very familiar with his writings. However, she mistakenly said it was “Igor” only because the name of the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky had quickly come to mind. When Evita described her dream’s tragic ending for the wolf, George wept. In that moment of dramatic empathy he declared that the name, Igor, must be his own. He then chose the surname of Gorsky simply because he felt its alliteration with Igor was fitting. From that point on, George Vassilopoulos was completely transformed in his rebirth as Igor Gorsky. He even took the step of legally changing his birth name to his adopted brush name. The origin of the name change is important to the end of this story because Evita’s creative path, which would lead her to become an Arhatic yogi, was always based on the prayer of St Francis of Assisi.

From Athens to Austin

Gorsky was born in Athens in 1936 and grew up in a seaside suburb during the Great Depression. His father was an attorney, who during World War II forged passports for Jews and helped them escape from occupied Greece. His mother’s nickname was “the General” because of a strong character that would not tolerate vulgarity or frivolity, and her ethics were impeccable. Blonde and blue-eyed, she exuded a regal presence — an important asset when her son was a youth.

As a teenager, he known as irreverent and controversial. He once found a discarded World War II revolver in the fields and brought it to school. The gun had no bullets, but that did not dissuade him from demanding that a girl to kiss him at gunpoint. Soon, a line of girls appeared wanting to be so “threatened.” When the headmaster found out, he locked George in the school’s coal storage house. The students soon gathered, trying to get in and share in his punishment. His favorite way to attract a crowd was to arrive on horseback at a chic cafe, earning a nickname from the girls — “George-on-the-horse.” He could provoke shock at a formal dinner when, after eating crabs and lobster, he would clean his fingers in the provided bowl of water — and then drink it to everyone’s disgust.

Despite his rebellious stage as teenager, he was a brilliant student during the five-year program at the highly selective National Technical University of Athens, known as the Athens Polytechnic. After graduating, he traveled to Austin where, in 1963, he entered the four-year Masters program in Chemical Engineering at the University of Texas. He graduated in 1966 but not before marrying Tralene Bailey, a fine art major in her junior year at the university. It was also around this time when he was recruited by two of the university’s professors — Franco Modigliani and Andrew C. Stedry — to join a think tank whose research into economic theory and consumer behavior in the stock market played a significant role in the creation of the Nasdaq securities exchange in 1971.1 Vassilopoulos’ expertise in chemical engineering quickly landed him a job with an oil refinery in Houston, and by the early 1970s he left to form a partnership that manufactured air conditioning systems for huge refineries in Saudi Arabia. After six years of focused work, he succeeded in making enough money that would last his lifetime.

Although the unexpected rebirth of the engineer George Vassilopoulos into the painter Igor Gorsky would be decades away, he was also interested in the surrealist approach in his wife’s paintings. She had always thought of him as a genius in mathematics, so she was surprised by his effusive encouragement when she had once suddenly decided to give up painting. “George, in his very demonstrative way, raised both of his hands in the air, fingers outspread as if to catch the light and throw it toward me,” she recalled, “He then gestured as he yelled, ‘Paint! Paint!’ On one occasion I yelled back at him, ‘Oh, if you want me to paint so bad, why don’t you paint?!’” When that marriage ended in divorce in 1983, Gorsky returned to Greece where he became even more passionate about the world stock exchanges.

The Catalyst for a Rebirth

Most art historians and critics are inclined to make sense of an artist’s career by placing their works in a timeline tracking quality. “Quality” is not an amorphous term. It is the assessment of innovation sharply tempered by its historical significance. Artistic achievements are compared to those of predecessors as well as peers. To be truly innovative is the opposite of being derivative. While bringing to light peaks of maturity in style and innovation, historians often approach the task assuming a linear methodology. Some career graphs show a bell curve where youthful innovation gradually built to a crescendo of achievement in midcareer and then stagnated in later years, trailing off languidly. Other artists showed signs of genius at an early age that aroused serious critical recognition but thereafter quickly disappointed, sliding down a steadily declining slope. Still others experienced an inauspicious start but took a lifetime to climb an upward slope toward success, ending brilliantly with a flash of vision in late career. Gorsky’s life’s work introduces the rarest of tracks, one where the odds were stacked against him. First, he had no academic training in art and did not commit to a life as a painter until midlife. Second, his eccentricities and inner turmoil made him an irascible character, irreverent and even antagonistic to those who could bring him recognition: curators, dealers, and collectors. Therefore, he accepted his journey of discovering a new technique that would lead him to canvases of sublime expression as a private one. He did not care if he risked being marginalized, overlooked, and forgotten.

Why would a chemical engineer turned stock market player commit the rest of his life to painting? Others late to the game include Jean Dubuffet [1901–1985], whose early career had been that of a vintner and wine négociant, only dedicating himself to painting in his early 40s. And, unlike one successful Parisian stockbroker — Paul Gauguin [1848–1903] — the catalyst for Gorsky was not a stock market crash that that drove him to art. It was an élan vital — Evita Myriam. Moreover, owing to his accumulation of wealth his new life in art began with a foundation of security. Indeed, his keen ability to accurately analyze the futures of companies kept him active in the stock exchange throughout his life even though every day he was far more consumed by the challenge presented by painting. From the beginning, he even embraced Evita’s preferred canvas size of 60 x 60 inches, chosen by her because the square connoted the infinite and was the wingspan of her open arms spread to that length. “When he began to paint, he entered a new life,” Evita explained. “Although he was always thinking outside the box before becoming an artist, when he began to paint he became liberated and changed profoundly. He used to say he has lived a few incarnations within this one.” The couple returned to Athens in 1990 and rented the house of the important collector George Costakis [1913–1990], whose collection was acquired by MOMus (Metropolitan Organization of Museums of the Visual Arts of Thessaloniki) in 1997. Thereafter, they divided their time between Athens and New York. “By the early 1990s Igor was producing large, beautiful works,” Evita recalled, “and he often painted through the night until 3:00 or even 5:00am.”

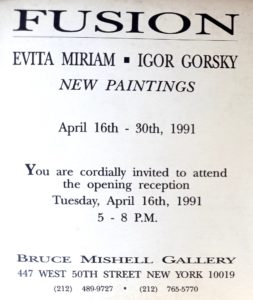

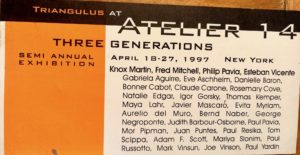

In New York, the couple had begun exhibiting together at small galleries beginning in 1991 and called themselves “Fusion” — and by 1994 they enjoyed a solo show at the Gerald Quinn Library Gallery at Fordham University. They were later represented by Rosenberg + Kauffman on Wooster Street in SoHo. In 1997, they moved to a townhouse on 4th and 12th Streets in Greenwich Village. They soon met Juan Puntes, a painter who in 1998 founded WhiteBox, a non-profit exhibition space in SoHo. Puntes specialized in giving visibility to artists who were under the radar and not shown in major galleries. He saw in Gorsky an edgy artist who was surprisingly pouring thick glossy automotive paint in the spirit of Paul Jenkins, but in a unique technique. “There was a veritas in both his life and his approach to painting,” said Puntes. “His ideas would change because his changing mood was imperative. He means what he does.” Puntes was aware that Gorsky’s mood swings, abetted by alcohol as a cover, followed the same pattern as the AbEx painters with chips on their shoulders, such as Pollock, Kline, and deKooning. Puentes introduced Gorsky and Evita to Philp Pavia [1911–2005], the sculptor and founder of famous AbEx group’s “The Club” on 8th Street. Pavia lived in a spacious loft at 810 Broadway below Union Square and urged Gorsky and Evita to rent the loft just below his. For the next three years they joined a group of twenty artists whose studios were at 14th and 6th Avenue, and under Puente’s curation they exhibited as “Triangulus” at Studio 14. “I was with him day and night for a long time,” recalled Puentes, who thought Gorsky might have been bipolar. “We had many dinners with the Pavias. For Igor, seeking self-respect was a necessity, and he would openly discuss his fantasies and confrontations. Once, he asked a serious collector why he was interested in buying a particular painting. When he considered the collector’s response to be unsatisfactory, he kicked him out.”

In New York, the couple had begun exhibiting together at small galleries beginning in 1991 and called themselves “Fusion” — and by 1994 they enjoyed a solo show at the Gerald Quinn Library Gallery at Fordham University. They were later represented by Rosenberg + Kauffman on Wooster Street in SoHo. In 1997, they moved to a townhouse on 4th and 12th Streets in Greenwich Village. They soon met Juan Puntes, a painter who in 1998 founded WhiteBox, a non-profit exhibition space in SoHo. Puntes specialized in giving visibility to artists who were under the radar and not shown in major galleries. He saw in Gorsky an edgy artist who was surprisingly pouring thick glossy automotive paint in the spirit of Paul Jenkins, but in a unique technique. “There was a veritas in both his life and his approach to painting,” said Puntes. “His ideas would change because his changing mood was imperative. He means what he does.” Puntes was aware that Gorsky’s mood swings, abetted by alcohol as a cover, followed the same pattern as the AbEx painters with chips on their shoulders, such as Pollock, Kline, and deKooning. Puentes introduced Gorsky and Evita to Philp Pavia [1911–2005], the sculptor and founder of famous AbEx group’s “The Club” on 8th Street. Pavia lived in a spacious loft at 810 Broadway below Union Square and urged Gorsky and Evita to rent the loft just below his. For the next three years they joined a group of twenty artists whose studios were at 14th and 6th Avenue, and under Puente’s curation they exhibited as “Triangulus” at Studio 14. “I was with him day and night for a long time,” recalled Puentes, who thought Gorsky might have been bipolar. “We had many dinners with the Pavias. For Igor, seeking self-respect was a necessity, and he would openly discuss his fantasies and confrontations. Once, he asked a serious collector why he was interested in buying a particular painting. When he considered the collector’s response to be unsatisfactory, he kicked him out.”

Ultimately, Gorsky was reticent to pursue gallery representation partly because his wealth and his philosophy allowed him to remain free of that need — while his unpredictable demeanor assured he would be following his own path. One of his gallerists, Stephen Rosenberg, recalled him as an intriguing but irascible character. “After finishing painting around 3:00am, Gorsky enjoyed hanging out in bars and getting into heated arguments,” he recalled. Evita confirmed that “He scorned money, he saw through flattery, and insulted mostly everyone. And as time passed, he became more and more disinterested in good manners.” She recalled one time when they attended the opening of an artist’s exhibition at MoMA. Gorsky approached the artist, who was wearing torn jeans splashed with paint, and said, “Man, why are you dressed in these torn jeans in your opening? Why do you have to dress as an artist? Don’t you have any decent pair of pants?” As Gorsky left the party he tossed his plastic cup of vodka over the staircase, showering people on the lower floor. He and Evita calmly descended the staircase as security guards rushed upstairs to find the troublemaker. Even at their own exhibitions, Gorsky’s impossibly caustic behavior created a multitude of awkward moments, driving away exasperated collectors.

Ultimately, Gorsky was reticent to pursue gallery representation partly because his wealth and his philosophy allowed him to remain free of that need — while his unpredictable demeanor assured he would be following his own path. One of his gallerists, Stephen Rosenberg, recalled him as an intriguing but irascible character. “After finishing painting around 3:00am, Gorsky enjoyed hanging out in bars and getting into heated arguments,” he recalled. Evita confirmed that “He scorned money, he saw through flattery, and insulted mostly everyone. And as time passed, he became more and more disinterested in good manners.” She recalled one time when they attended the opening of an artist’s exhibition at MoMA. Gorsky approached the artist, who was wearing torn jeans splashed with paint, and said, “Man, why are you dressed in these torn jeans in your opening? Why do you have to dress as an artist? Don’t you have any decent pair of pants?” As Gorsky left the party he tossed his plastic cup of vodka over the staircase, showering people on the lower floor. He and Evita calmly descended the staircase as security guards rushed upstairs to find the troublemaker. Even at their own exhibitions, Gorsky’s impossibly caustic behavior created a multitude of awkward moments, driving away exasperated collectors.

On the other hand, Gorsky was generous and loved unpretentious people. “Every time Igor got into a taxi he would ask the driver questions about his life,” recalled Evita. “He always gave money to the homeless, sometimes emptying his pockets. I remember when he gave $300 to a homeless person. Stunned and in tears, they would always ask him who he was. One even asked why he saw a halo around his head.” In one incident, Gorsky was attacked near his studio late at night by a man who put a knife to his throat. Igor said to him “Do you really want to kill an artist?” He then handed him $60 and invited him to have dinner with him. He took the thief to a Greenwich Village café at 3:00am and asked him to tell him his story.

How a New Visionary Arose from Cathartic Anger

Despite Gorsky’s typically casual appearance, another side of him enjoyed dressing in Armani suits and taking Evita to the finest gourmet restaurants in Geneva, Rome, and other European cities every year. Yet, constantly introspective, he confided to her that he had various “sides” to him that emerged as seven distinct personalities with their own names and histories. They included George, Igor, Dorovin, Archie, and Liliput, for example. Each New Year, a certain personality would emerge to give Evita a present and she would reciprocate with a gift appropriate for each personality. However, she recalled one disturbing incident early in their marriage. “Once in Prague, one of his personalities — the stern one that never appeared — broke the glass table of our hotel room with his fist when I said that I loved him. That was in our first year together. He was a sceptic and very insecure in matters of love.”

During his first few years of painting — 1988–1991 — Gorsky struggled to find his own artistic voice. He was self-taught, experimenting with styles and techniques. Despite some intriguing works, the process was difficult and frustrating. His first paintings during this period were inspired by Abstract Expressionism, and a series of cross paintings would soon appear. “Igor had what he mocked as Christ complex,” explained Evita. “All the crosses were his feeling of being betrayed and crucified or were his increasingly deeper level of compassion for Christ’s suffering. He was experiencing the suffering of Christ as if it were he. I can safely call Igor heroic in character because he was honest, had integrity, was generous and fearless. If he only did not have such a dark side, and did not drink so much, I would call him a Giant.”

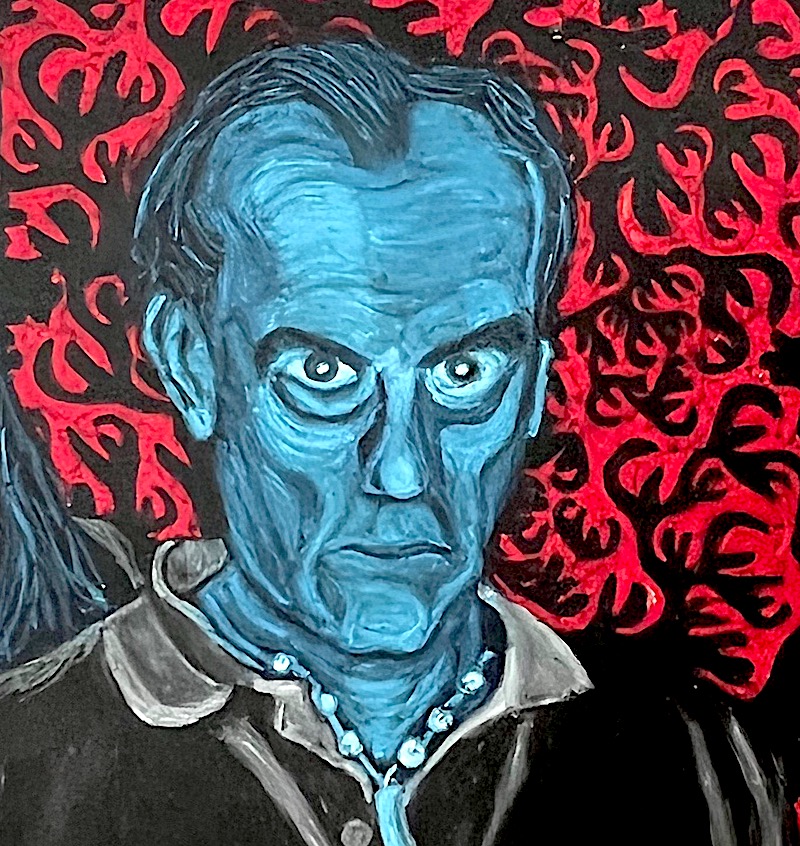

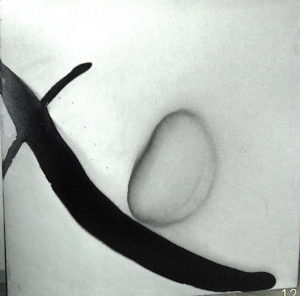

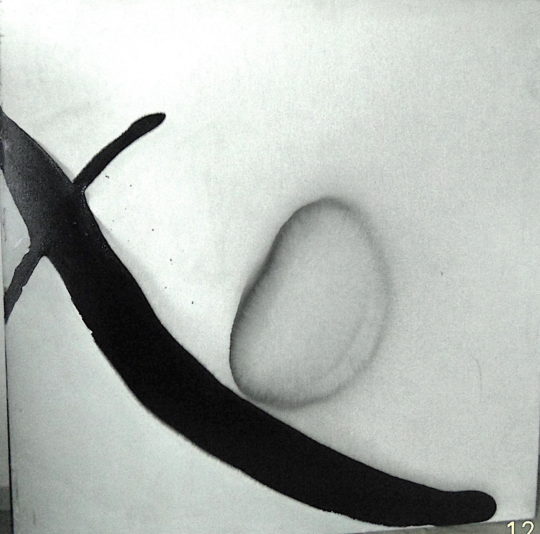

Another significant theme that emerged in this early period was a series of 60-inch square self-portraits on black backgrounds. These canvases — painted with slashing brushwork and sometimes splattered and scraped — are simplistic yet nightmarish. Each typically features two menacing eyes and a gaping mouth bearing sharp teeth, the whole reflecting a face more alien than human. A more brutal manifestation of Gorsky’s anxiety — one that no one ever saw — was the series of these dark faces he slashed with a knife (left). He stabbed the eyes and the mouth, leaving gashes that seem to be testaments to the loathing of one of his personalities. These periodic slashings are violent, unlike the rhythmic vertical cuts of canvases found in the Concetto spaziale series of Lucio Fontana [1899–1968] created the 1950s–60s. Gorsky’s attacks would have some psychoanalysts considering that he may have had a dissociative identity disorder, especially in consideration of the various personalities he described.

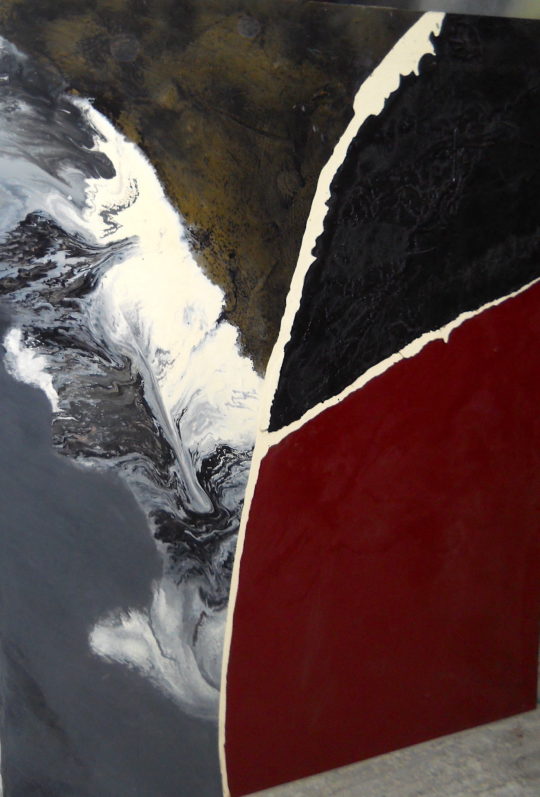

Gorsky released his anger by slashing angry faces into the 60 x 60 inch black canvases. This progression of images shows how he eventually discovered new abstract compositions by filling the cuts by backing them with black or red canvas.

Evita illuminated his periodic slashings as self-destruction. “The slashed faces were self-portraits. His anger was towards himself. He hated himself and slashed the paintings when he felt his work would never be understood or appreciated. His slashes also showed his irreverence towards creativity and art, and these paintings became exhibits of his pain.” However, the anger that caused destruction evolved into a creative discovery when Gorsky became intrigued by the negative space caused by the slash-marks. He noticed that when a slashed canvas was stacked in front of a canvas of bright red, the wounds caused by the knife created a pattern of red slits that danced across the canvas. The two works at right are examples of how, from that point on, he moved beyond the grimaces and into non-objective abstraction by inserting swaths of painted canvas behind the slashes.

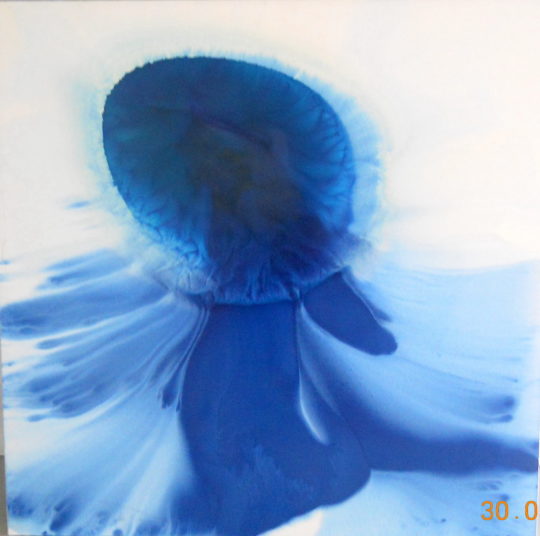

Evita described Gorsky’s painful visages as reflecting the inner turmoil in his mind, and how they may have served as cathartic exercises. However, as Gorsky perfected his technical skills with pouring, new themes came to life that are in sharp contrast to the slashed works. These self-portraits — pure pourings — are an entirely different matter. As he mastered the controlled pour, he created new worlds, cosmic atmospheres, and even creatures of fantasy. The sophistication and patience in the creation of these inner landscapes caught the attention of James Cavello, Director of the Westwood Gallery in SoHo, who mounted a successful solo exhibition in 2000. Gorsky never expressed to anyone that these gesturally explosive abstractions were self-portraits releasing his demons, but historian Donald Kuspit intuitively recognized the emotional richness of their angst when he titled his exhibition essay, “Abstract Terribilitá: Igor Gorsky’s Paintings.” He defines terribilitá as “the sense of divine fury or cosmic energy, evoking a sense of dreadful awe and ecstasy” as he describes a face emerging from the darkness of the canvas (below). “This face is grotesque, certainly monstrous, even devilish — the face of an underworld animal. Gorsky has made a painting that is at once abstract, expressionistic, and surreal — a painting that shows the vivid, fresh hallucinatory and visionary effects that are still possible with the paranoid-critical method, as the surrealists called it, and that is full of expressionistic intensity, yet maintains the awesome dignity and detachment of the abstract sublime.” Although Kuspit did not know Gorsky’s ferocious creatures were expressing the artist’s own deep-seated fears, he aptly concluded, “Gorsky has aggressively restored the sense of the alien, making modernism once again uncanny and urgent. Recasting modernism in his own dynamic terms, he recovers its innovative spirit and power. He has used modernist methods to make new visionary jewels — his sublimely abstract paintings, with their fresh tensions, drive, and hallucinatory vitality.”

Kuspit highlights the drama unfolding in the untitled No. 120 from 1998: “The lower half of the painting is a steep, black, inverted curve, from which a kind of smoky magma streams — or it steams? — to form the upper half of the work. The tension is palpable along their border, and there is further tension within the turbulent, even violent gestural half, for again what looks like an eye — black, with no glint of luminosity appears, evoking an animal head, perhaps that of a hawk. [Gorsky saw it as a horse.] Indeed, Gorsky’s hallucinatory creatures seem predatory, although that may be my interpretation of their power. Indeed, the evocative power — the unconscious resonance — of Gorsky’s paint is great, a result of its relentless physical power.”

Kuspit describes another monstrous face that appears in No. 65 from 1999, as suggested by the two round white holes in the black ground. “Again the work is divided against itself: a smooth, opaque blackness dominates, from which a tangled mesh of wild branch-like gestures grow. But it is the interplay of black and white surfaces — painterly black flatness finessing smooth white flatness — that generates the most drama and tension. Void seems piled upon void, creating a powerful sublime, underworld effect — a sense of infinite depth as well as cosmic space.”

Regardless of any attempt to psychoanalyze Gorsky’s underlying emotional commitment to a life in art, his behavior certainly reflected its parallel with the shapeshifting Nagual described in the writing of Carlos Castaneda. Another analogy is Shiva — that primary deity in Hinduism whose great powers could generate both destruction and creativity. A later canvas from 2013 (right) explodes with outwardly streaming orange flames bursting from a calm sky-blue background while a black figure with a cyclopean eye may have just been birthed — or is desperately fleeing — a volcanic eruption.

Regardless of any attempt to psychoanalyze Gorsky’s underlying emotional commitment to a life in art, his behavior certainly reflected its parallel with the shapeshifting Nagual described in the writing of Carlos Castaneda. Another analogy is Shiva — that primary deity in Hinduism whose great powers could generate both destruction and creativity. A later canvas from 2013 (right) explodes with outwardly streaming orange flames bursting from a calm sky-blue background while a black figure with a cyclopean eye may have just been birthed — or is desperately fleeing — a volcanic eruption.

“Igor felt like a child obliged to walk through a dark tunnel having the light of his innocent heart as a guide,” recalled Evita. “He felt he had to brave the darkness; he sometimes felt the darkness would not allow him to be the light. He drank alcohol, smoked like a chimney, putting out the cigarettes after three or four puffs, he used a language that could make an 80-year-old blush, but his real self was like a child.” The only benefit of Gorsky being a chain smoker is that he carefully filed his empty cigarette packs in a drawer after using a marker pen to note the dates when he painted each work.

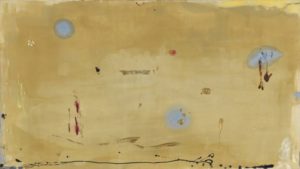

Kuspit further points out that not all of Gorsky’s creatures were fierce. Some appear to be cosmic landscapes. Others suggest the dream worlds children conjure while interpreting the changing formations of cumulus clouds on a warm summer day. Kuspit observed, “Void seems piled upon void, creating a powerful sublime, underworld effect — a sense of infinite depth as well as cosmic space…I am trying to suggest the uncanny evocative power of Gorsky’s paintings — their emotional richness. But what seems especially important about them is that they are a kind of cosmic space — a landscape of the infinite, as it were.” As Gorsky became increasingly driven to perfect his pouring technique he became immersed in a state of calm concentration. With his newly found sense of boundless freedom his self-confidence became firmly instilled. In several canvases he even boldly assaulted the drip-action paintings of Jackson Pollock, canonized as the ultimate defiant painter who changed the course of art history. These attacks were launched not simply to be blatantly irreverent but to share with us how gestural abstraction can retain its power yet reveal to us new cosmology. And that required getting beyond Pollock. His bold offensive is marked in the following three exemplative canvases from 2004, beginning with No.47. Pollock reveled in the paradox of flatness while inviting the viewer to contemplate the sublime depths of the microcosm and the macrocosm. Gorsky began to approach No.47 in this way. The background of this painting could well be seen as a light blue sky, over which Gorsky dripped layers of dazzling lace-like webs in black and orange-brown. However, he abruptly halts the Pollock dance by detonating a bomb on its surface. Using spray paint, he spewed clouds of noxious blood-red smoke seen billowing upward, drifting ominously to the northwest.

Close inspection of the damage at ground zero is seen in No.3. The signature bold black gestural strokes of its abstract expressionist surface are still visible under a diaphanous white scar tissue but the whole surface is now overlaid by a pattern that appears to be that of cracked glass — reinforcing the fragility of the New York School’s sacred flatness. Traces of the red still surround the point of impact, a black hole at dead center. This focal point is not just evidence of the attack but a portal, beyond which lies Gorsky’s world. Passing through that portal we discover another world behind Pollock’s surface. This is a world where the power of color and shape create such exotic spaces — both inviting and terrifying — that we feel compelled to ground ourselves in recognizable landscape terms lest we get swept away. This is a realm where Gorsky has taken control of his dreams. This is seen in a third untitled canvas (below), which also shares an energized center. Black tentacles reach outward from a black core, perhaps feeding off the area of red spray paint at the left and bottom.

Gorsky’s response to abstract expressionism thus evolved from a fury that came under control after the medium and pouring technique were mastered, allowing a deeper surrealist contemplation of space, form, and color. For those who grew up in the 1960s his dreamscapes are visual reminders of the presaging introduction the popular weekly sci-fi television show, The Outer Limits:

There is nothing wrong with your television set… We are controlling the transmission. We will control the horizontal. We will control the vertical. For the next hour, sit quietly and we will control all that you see and hear. You are about to participate in a great adventure. You are about to experience the awe and mystery which reaches from the inner mind to — The Outer Limits.

Gorsky’s manipulation of heavy enamel pigments to achieve extraordinary effects began as delightful “accidents” that revealed new potentials in painting. Most important, those effects came to be carefully controlled to create new worlds, drawing in viewers by the paintings’ sheer size, being sixty inches square. Yet these paintings are more than controlled hallucinations of the cosmos. Do they document that moment of convergence where the most primal forces of energy, both creative and cosmic, burst into color to form matter itself? Or, are we witnessing a cataclysm? Unquestionably, they are a compelling invitation to a way of seeing that is forceful, provocative, and magically beautiful. But make no mistake. Gorsky was in complete control.

The Drive Toward the Sublime

Some artists changed their names just as they were beginning to develop what they felt were their own unique styles. Robert Henri was Robert Cozad. Arshile Gorky was Vostanik Manuk Adoian. Man Ray was Emmanuel Radinski. Mark Rothko was Marcus Rothkowitz. Morris Bernstein was Morris Louis. The happy consequence of name changing was the reinforcement of their personas. Gorsky’s epiphany, and his sudden immersion in painting, generated within him a responsibility to discover his own unique form of expression.

Beginning in the early 1990s, a succession of three series emerged — the Pours — the great majority of which are 60 x 60 inches. The Pours (illustrated this page) began in 1992. The Veils began in 1995, and the Wedges began in 1997. Each series were controlled expressions confirming his ability to attain the sublime. Gorsky never corrected an unwanted pour; instead, he always added. “After contemplating a painting, he would stand up decisively, return to it, and would by all appearances ruin it by pouring over the best part of it with a stripe of color,” Evita recalled. “It never failed to amaze me that the painting ended up a hundred times more beautiful and powerful than before. He could guide the course of every drop of paint, and he knew exactly how each twist and turn of the canvas could even create lacey patterns or concentric circles.”

Being an Outsider, Gorsky never paid attention to the revolution in styles that had begun at the end of World War II when the Abstract Expressionists of the New York School wrested from Paris the title of capital of the art world. He never paid attention to the contemporary art market as it steadily heated up during the 1950s — or the seminal article in LIFE magazine in August 1949 that featured a two-page spread showing the irascible Jackson Pollock in front of one of his big paintings. The headline read: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” He never paid attention when, in the early 1960s, David Rockefeller exhibited the country’s first major corporate art collection throughout every office at his new 60-story headquarters on Wall Street for Chase Manhattan Bank. And he never paid attention when, throughout the following decades, a succession of disparate movements — Color Field, Pop Art, Minimalism, Op Art, Hard Edge, and Minimalism — presented overlapping assaults reacting against, or morphing from, Abstract Expressionism.

Gorsky’s life-changing epiphany in 1988 had affirmed he would become a painter — but he was unclear about how he would create a style and technique that reflected his noble quest to make transcendence visible — and perhaps even serve as his salvation. Upon occasional museum visits, Evita exposed him to the wave of isms since mid-century. Gorsky recognized the flow toward a mythic approach to bold mark-making by the Abstract Expressionists — led by Jackson Pollock, Willem deKooning, and Franz Kline. He saw a balancing force in the first Color Field painters — Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still — with their canvases of a transcendental calm. That mantle was assumed by Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Paul Jenkins — the leading Color Field painters of the 1950s–60s. Yet, before they were pure pourers they had started off as AbEx mark-makers, as did Gorsky. Frankenthaler increasingly adopted pure pouring by the late 1960s. Paul Jenkins started titling his pours Phenomena in 1960 — bearing some affinity to Gorsky’s pours that imply cosmic landscapes. By the 1970s Jenkins’ pouring presented petals or fingers of bright primary colors, and he later circled back to the bravura brushstrokes of AbEx compositions. Morris Louis began a series of poured paintings he called Veils in 1954, and in a few years these assumed what seem to be the shape of a grand monolithic altar in earthy brown tones or as curtains broadly stretched across a stage. In his later Unfurled series one finds colorful diagonal stripes leaning against the sides of the picture plane, each forming a triangular corner; and, his Stripes series bunches those stripes of primary colors together vertically.

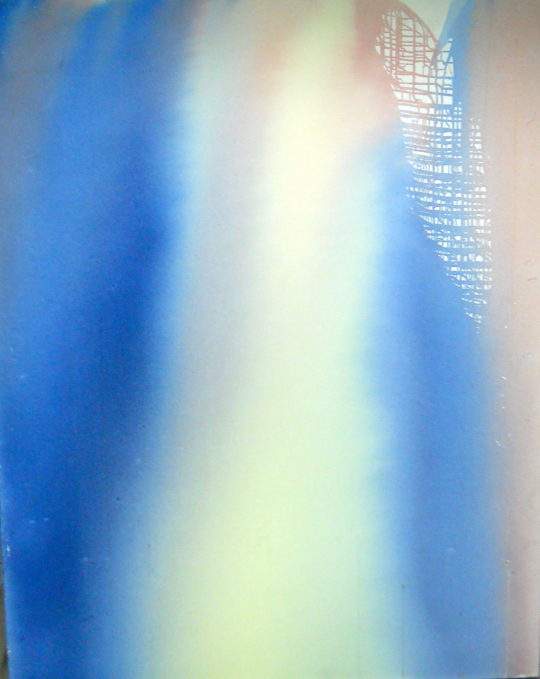

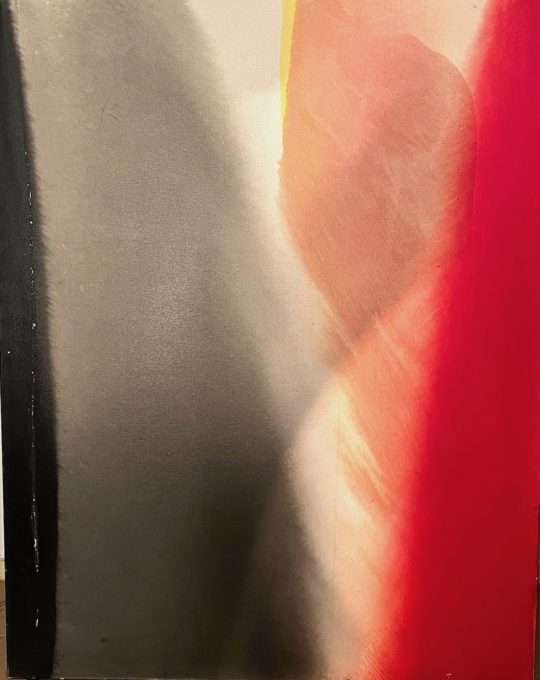

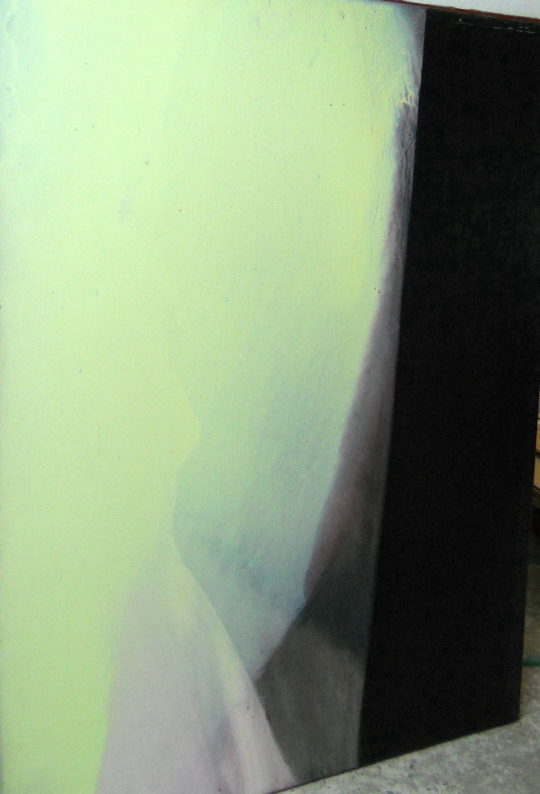

Gorsky started his breakthrough Veils series — all vertical six-foot canvases — in a spirit held in common with the earlier Color Field pourers: a passion for controlling broad swaths of color to induce a boundless immersion into the transcendental. However, instead of focusing on placing colors and shapes in structural roles, as did Louis with his Unfurled and Stripes series, Gorsky’s whole invites us on a cosmic voyage while encouraging the eye to move beyond the canvas edges in all directions.

One of the ways in which Gorsky parted significantly from the Color Field painters was his choice of medium. His predecessors let their diluted their water-based acrylic pigments soak into and stain the canvas. Gorsky’s medium was a glossy oil-based auto enamel with which he conducted many different experiments in an open spirit of discovery. It took several years before he had truly mastered the pouring of this unusual medium. He learned how viscosity affected the pouring and then controlled it with different dilutions with white mineral spirits. His canvases were layered with pours, one atop another. Ultimately, the Veils most consistently reflect Gorsky’s attainment of the higher spiritual state he was seeking. After all, when he started his breakthrough Veils series, he had no intention of slavishly following the painters easily identified as his predecessors. His discovery of the sublime in the Veils was welcome redemption for the ferocity and anger spewed by his less attractive personalities. “The veils were to him, the light,” declared Evita. “They were made of light and elation. His colors were so authentic in their combination, and they evoked such pure emotion and unaffected integrity.” Gorsky never thought of his works as progressing and being completed chronologically in several series. Instead, he was inspired to return to these themes with an innocent eye throughout his three decades of painting. Evita likened him to The Little Prince of St Exupéry — the child prince who traveled to six planets, each time observing how adults lacked the perception and enlightenment of children. He consistently retained an innocent perception as he contemplated beginning each canvas.

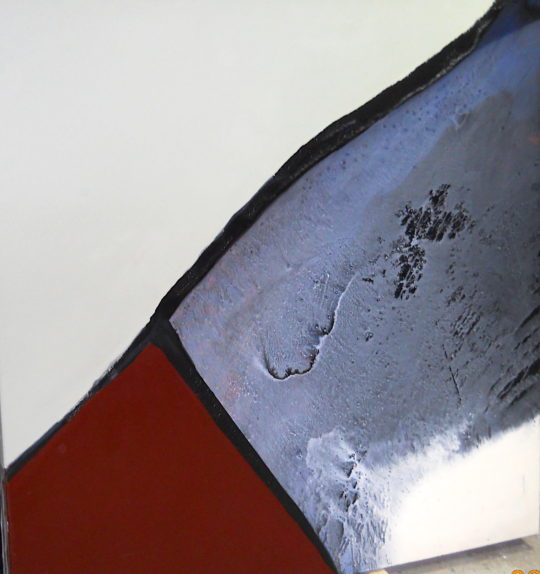

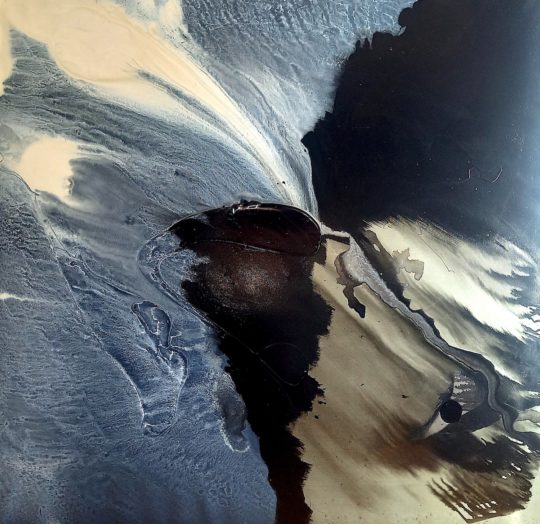

Gorsky’s spirit of approach to creating art was one of immaculate perception. Evita noted, “Each work was a mystery to him before it acquired its personality.” This observation also applied to his last series, the Wedges. Now, he carved out the picture plane so that it was clearly partitioned by white, black, or red borders that defined either triadic or quadratic wedge-like spaces. Some of those wedges frame a solid color. Others frame a pouring — a glimpse into one of Gorsky’s cosmic worlds replete with inferences to spiral nebulae or providing an astronaut’s view of a massive estuary. As wedges, these glimpses from space and of space make it seem as if we are looking through a camera’s open shutter blades.

Gorsky’s spirit of approach to creating art was one of immaculate perception. Evita noted, “Each work was a mystery to him before it acquired its personality.” This observation also applied to his last series, the Wedges. Now, he carved out the picture plane so that it was clearly partitioned by white, black, or red borders that defined either triadic or quadratic wedge-like spaces. Some of those wedges frame a solid color. Others frame a pouring — a glimpse into one of Gorsky’s cosmic worlds replete with inferences to spiral nebulae or providing an astronaut’s view of a massive estuary. As wedges, these glimpses from space and of space make it seem as if we are looking through a camera’s open shutter blades.

With each of his three mature series — Pours, Veils, and Wedges — Gorsky pushed himself beyond the works of the Color Field painters who preceded him. Specifically, in his uniquely visionary approach to the 60-square-inch Pours he could swing between completely non-objective abstraction to the suggestion of anguished faces, hallucinatory creatures, and cosmic topographies. In the Veils he switched to a 72 x 48-inch vertical format and painstakingly poured what seem like forces of graceful transition applied to Hard Edge and Minimalist paintings, converting them to sacred shafts of light.

Return to Athens

In 2000, after eleven years of marriage, the couple that was Fusion broke up. That year, Evita exhibited without Gorsky at Postmasters and he continued with his planned solo exhibition at Westwood Gallery. However, it was emotional upheaval that made Gorsky return to Greece for good in 2001. While he never sought another gallery, Westwood did mount a second solo exhibition in 2006 composed of different paintings that had been selected earlier.

Gorsky settled into a large apartment in central Athens in the chic and upscale Kolonaki neighborhood bordered by the southwestern slopes of Lycabettus Hill. He also found a spacious studio nearby. Soon, a “court” of artists, filmmakers, students, poets, musicians, and eccentrics formed around him, with Evita remaining his confidant and critic. Among his most devoted friends were Hal Ludacer, a model and artist who ran in Andy Warhol’s circle, was a regular at the Mudd Club with his friend David Bowie, and later played a fashion show model in the Basquiat film “Downtown 81.” Other creatives included the screenwriter and director Ioanna Tsinividi and the famous illustrator and animation artist Roberto Prual-Reavis. Evita introduced Gorsky to Nicholas Bartsokas, who she had hired for her restaurant, Moita, on the island of Hydra. Earlier, Bartsokas had earned international renown as chef of several Michelin-star restaurants. In an open house atmosphere, Gorsky generously shared his own culinary skills, which his guests called “Mother Food.” A common sight in the morning was guests scattered about in bedrooms and on sofas, just waking up. For the next twenty years he was prolific in pursuing his poured canvases, but despite the encouragement of the cultured friends who surrounded him he had no interest in pursuing any galleries. Plus, added Evita, “I suppose his personality would not make it easy on any dealer.” Not surprisingly, while new friendships helped him to bloom further, his liberation found new extremes, releasing his dark personalities as well as those thriving in the light of creativity.

Gorsky settled into a large apartment in central Athens in the chic and upscale Kolonaki neighborhood bordered by the southwestern slopes of Lycabettus Hill. He also found a spacious studio nearby. Soon, a “court” of artists, filmmakers, students, poets, musicians, and eccentrics formed around him, with Evita remaining his confidant and critic. Among his most devoted friends were Hal Ludacer, a model and artist who ran in Andy Warhol’s circle, was a regular at the Mudd Club with his friend David Bowie, and later played a fashion show model in the Basquiat film “Downtown 81.” Other creatives included the screenwriter and director Ioanna Tsinividi and the famous illustrator and animation artist Roberto Prual-Reavis. Evita introduced Gorsky to Nicholas Bartsokas, who she had hired for her restaurant, Moita, on the island of Hydra. Earlier, Bartsokas had earned international renown as chef of several Michelin-star restaurants. In an open house atmosphere, Gorsky generously shared his own culinary skills, which his guests called “Mother Food.” A common sight in the morning was guests scattered about in bedrooms and on sofas, just waking up. For the next twenty years he was prolific in pursuing his poured canvases, but despite the encouragement of the cultured friends who surrounded him he had no interest in pursuing any galleries. Plus, added Evita, “I suppose his personality would not make it easy on any dealer.” Not surprisingly, while new friendships helped him to bloom further, his liberation found new extremes, releasing his dark personalities as well as those thriving in the light of creativity.

Everyone who knew Gorsky soon came to recognize his mood swings. He became progressively distrustful, to the point where his paranoia made him so certain of betrayal that he alienated everyone until one-by-one they abandoned him. Even Evita could not help him because of his pride and stubbornness. He even attempted self-immolation but failed, instead nearly burning down his apartment. A few friends were adamant that he be placed in a psychiatric hospital. “Some may say that Igor had dementia towards the end,” recalled Evita, “but I think that he was just terrified of the negative energies that all this irreverent living had attracted.” On December 5th, 2021, Gorsky was so anxious about anticipating his death — but refusing to die at home — that he packed a suitcase and hopped a taxi to a hotel as the more suitable venue for his demise. Along the way he suffered a heart attack and was instead taken to a hospital. Curiously, the doctors could find no problem and were so impressed by his liveliness and mental acuity that they released him that evening. One of his last remaining friends, Dimosthenis, picked him up and took him back home. Gorsky asked him to take his suitcase inside while he rested on the steps. When Dimosthenis returned, he found that Gorsky had passed away.

Epilogue — the Fate of a Collection

Gorsky’s legacy is an extraordinary chapter in contemporary international art — and is inseparable from his life with Evita as Fusion. In 2000, after Evita exhibited alone at Postmasters, she returned to Athens where she entered another life phase. She was an artistic polymath constantly pursuing several creative paths at the same time. For example, she was a jewelry designer, and hundreds of her innovative works were acquired by the Benaki Museum in Athens. In women’s fashion, the country’s famous designer — Loukia — asked her to come up with a special jewelry component for a major bridal runway event. Evita created glass butterflies that bounced gently upon invisibly thin silver wires over the brides’ heads. The next day, the reviews in the media excitedly reported about the fabulously surreal kaleidoscope of butterflies that floated like white clouds over the models. During this time, she was also attracted to the culinary arts and launched what became a famous gourmet restaurant, Moita, on the island of Hydra. Her passion further extended into design and architecture, resulting in the renovation of several important apartments in Athens. She also pushed her own image experiments in paintings, which matured into three series — Knowledge from the Hyperconscious, Spiritual Visions, and Prophesies. “I did not like to repeat myself.” she declared. “My tendencies were to make beautiful things and then let them go, never repeating the experience.”

However, it was while living as a recluse on the island of Tinos in the Cyclades where she realized her life’s essence and talents as she painted, wrote poetry, and researched Pythagorean arithmosophy. By 2010, she had become a Pranic Healer — the most abstract of all the arts — and an Arhatic yogi and life coach. Evita concludes, “I placed all that I was at the feet of the Master and transmuted it into a path of aspiration.” Accordingly, Evita’s purpose is to sell Gorsky’s paintings (and her own) to finance the creation and maintenance of a non-profit refuge for mothers with children who will also take charge of an orphan. Her vision centers on a non-institutionalized safe haven, which she will call “Heaven on Earth” — and which will provide all needs, including supplementary education for the children for living with inner peace and self-confidence. Also included will be a small animal shelter as well as a free summer camping place for poor families. Those sheltered will be given clothes, food, and toys for the children. She also intends to create a feeding program for the area’s elderly. “My philosophy of compassion breeds fearlessness,” Evita says. “When we place ourselves in the position to give freely, the universe constantly provides.” She continues to live a life of essence, healing people’s lives, and helping them find their Purpose.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Footnotes

1 Franco Modigliani [1918–2003], a professor at M.I.T. from 1962–1988, won the Nobel Prize for his pioneering research in several fields of economic theory and practical applications for the stock market. His autobiography, Adventures of an Economist, was published posthumously in 2001. He was joined by Andrew C. Stedry, who was best known for his research on organizational goals and his 1965 book, Budget Control and Cost Behavior.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks go to James Cavello, Director of the Westwood Gallery, for his story on discovering Gorsky in 1995 and subsequently representing him; to Juan Puntes for his insights on the era and Gorsky the man — his achievements and his personality; to my colleague Donald Kuspit for his perceptive psychological and formal insights into Gorsky’s vision in his essay “Abstract Terribilitá: Igor Gorsky’s Paintings” [Westwood Gallery, NY, 2000]. His observations inspired my essay, “Igor Gorsky — Outer Limits” for the artist’s second solo exhibition and catalogue [Westwood Gallery, NY, 2006]. Because Gorsky returned to Athens in 2001 I never got to meet him. Fortunately, I have Evita Myriam to thank for her crucial insights portraying the artist she loved and understood better than anyone.

Sincere thanks go to James Cavello, Director of the Westwood Gallery, for his story on discovering Gorsky in 1995 and subsequently representing him; to Juan Puntes for his insights on the era and Gorsky the man — his achievements and his personality; to my colleague Donald Kuspit for his perceptive psychological and formal insights into Gorsky’s vision in his essay “Abstract Terribilitá: Igor Gorsky’s Paintings” [Westwood Gallery, NY, 2000]. His observations inspired my essay, “Igor Gorsky — Outer Limits” for the artist’s second solo exhibition and catalogue [Westwood Gallery, NY, 2006]. Because Gorsky returned to Athens in 2001 I never got to meet him. Fortunately, I have Evita Myriam to thank for her crucial insights portraying the artist she loved and understood better than anyone.

Gorsky Pours, Veils, and Wedges

-

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Wedge Series (No.20) 1998, 1998

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Wedge Series (No.23) 1997, 1997

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Wedge Series (No.22) 1997, 1997

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Wedge Series (No.21) 1997, 1997

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.1) 2000, 2000

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.4) 1999, 1999

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.3) 1999, 1999

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.32) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.31) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.30) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.19) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.13) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.12) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.6) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.4) 1998, 1998

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Veil Series (No.13) 1996, 1996

72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.1) 2011, 2011

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.3) 2010, 2010

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.2) 2010, 2010

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.1) 2010, 2010

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.1) 2008, 2008

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.4) 2000, 2000

50 x 50 inches (127 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.2) 2000, 2000

50 x 50 inches (127 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.1) 2000, 2000

50 x 50 inches (127 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.4) 1995, 1995

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.3) 1995, 1994

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.4) 1994, 1994

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.3) 1994, 1994

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.2) 1994, 1994

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled from the Pour Series (No.1) 1992, 1992

60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm)