Inside An Interstellar Artist’s Mind World

The pantheon of American Art has gradually been granting admission, long overdue, to artists largely overlooked. One focus in this field of rediscoveries is upon the Abstract Expressionist painters, many of whom were based in New York, with others scattered around the country. The names of these artists are finally entering the critical discourse and their works are being compared to those of their well-known peers, a circle that included Pollock, de Kooning, Gottlieb, Kline, Motherwell, Newman, Reinhardt, Rothko, Still, and Tobey. Art historians are like archeologists who have just discovered a prospective excavation site. We are intrigued when we dig up artifacts revealing true innovation. We are challenged to uncover why such an artist would have disappeared from the competitive art circles and become buried for generations. Discovering Fuller Potter is like arriving fresh to the scene of one of those newly roped-off excavation sites. How did he slip into obscurity? Why was the artist not afforded the critical recognition he deserved? In answering these questions, and displaying his work and his writings, we gain the satisfaction of correcting an oversight while expanding our understanding of the scope and depth of contemporary American painting.

Born in New York in 1910, Fuller Potter was a little-known member of the city’s first-generation of Abstract Expressionists. That peak period for this group ran from the late 1940s to the mid 1950s before ultimately giving way to a series of new movements, including Pop Art, Hard Edge, Op Art, and Minimalism. Several decades later, we art historians began to dig deeper into the Abstract Expressionist movement, delighting in the discovery of artists of original vision who had become marginalized for often fascinating reasons. Fuller Potter was one of them. A drunken binge with Jackson Pollock in 1948 was the catalyst that drove a fearful Fuller Potter to join Alcoholics Anonymous. Less than two years later he quit Manhattan altogether and moved to an old farm in Ledyard, Connecticut. There he bloomed as a prolific lyrical expressionist — however eccentric and reclusive.

Upon Potter’s death in 1990 his studio and barn were packed with paintings. In July of 1994 these paintings and his life story appeared destined to be buried forever. His son Dan, also an artist, arranged a tag sale and took out classified advertisements in the local newspapers bearing the ominous title, “Buy or Burn.” Dan scattered hundreds of works about the farm in Ledyard, hanging them up and leaning them against the outside walls of the artist’s studio, barn, and thickets while many were spread about the lawn. The advertisement drew many curious neighbors and several disconcerted artists but no art historians. At the end of the day many works had been sold and some were given away. The remaining works were amassed in a big mound and, incredibly, set ablaze. While psychoanalysts may interpret this conflagration — likely a first in American art history — as the dramatically overt satiation of an Oedipus complex, the artist’s son was not completely crazy. Fortunately, he was wise enough to have sacrificed only those works on paper or canvas that he felt were in poor condition or of lesser quality. However, five years later, he held a second “Buy or Burn” event, for which the newspaper reported, “Fuller Potter’s Art Will Sell or Burn on Saturday.” The newspaper followed up article “From Art to Ashes” after he created another pyre of victims. In the end, most of the works had been sold, given away, or turned to ashes.

1

Decades later, it took many years to locate the owners of the paintings and reassemble the pieces of the Potter puzzle. It was as if the ghost of this extraordinary artist had to run through a post-mortem gauntlet in order to stand any chance at achieving critical recognition. Throughout his life Potter frequently used his diaries to express his disdain for another type of gauntlet that he and all other artists were obliged to pass as they tried to promote their careers — the visibility afforded by exhibiting at clubs, competitions, museums, and especially the commercial galleries. Even though he had found representation in galleries in New York since 1932 he quickly became focused upon the act of making art and any urgency for self-promotion was often dismissed.

When art historians stumble across sites that were supposed to have remained buried, they are obligated to become cultural detectives. After pouring through diaries and examining hundreds of paintings and drawings that can be favorably compared with those of Potter’s better-known peers, an explanation is sought to explain why his works were nearly forgotten. Historically, one of the biggest reasons for this unfortunate fate has been studio fires in which an entire life’s work went up in smoke. Another is the Great Depression, which ended many promising careers. Others were simply reclusive by nature, irascible characters, at odds with the world. Add to this list a host of psychological problems, including addiction to drugs and alcohol. Some suffered from agoraphobia and others were tormented by psychotic breaks. Finally, a select few were possessed of such wealth that they could afford to avoid the gauntlets of competition but remain steadfast in pursuing their artistic visions. Necessity did not press upon them the need to have their work promoted before the public. For Potter, several of these problems — alcohol, wealth, and eccentricities — conspired to shape his fate.

On April 26, 1910, shortly after Halley’s Comet soared near Earth, Joseph Wiltsie Fuller Potter, Jr. was born in New York. He grew up in the posh Murray Hill neighborhood on East 36th Street. When Fuller was a boy his father headed the New York Police Department’s special bomb squad during World War I. Working closely with the War Department’s Intelligence bureaus, he was responsible for foiling bombing plots by German spies and agents. He went on to head Potter & Co., a Wall Street investment firm and member of the New York Stock Exchange. His mother, Mary Barton Atterbury, was of old New England lineage and her father was the law partner of a former governor of New York. Her father, Harold Otis, was partner in a major law firm with Nathan L. Miller, the former governor of New York.

Fuller Potter’s life soon revolved around on the Upper East Side, living first on East 55th Street and later on East 64th Street. As a little boy he suffered from osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone that brought him acute pain, but managed to get through St. Bernard’s School. In 1925 he left to attend the Groton School in Massachusetts. There he was a member of the choir, the orchestra, and the school’s fife & drum corps. He studied art under Kleber Hall, a painter-etcher and musician who was the first major catalyst for stimulating in the boy a love of both art and music.2 According to his brother, Jeffrey Potter, “Fuller got through Groton without studying. He had one of those minds.”

After graduating from Groton in 1929, the Potters moved to 333 East 57th Street. Fuller spent the summer painting and experimenting with abstract sketches at Shinnecock Hills, where he built a shingled shack in the dunes by the bay. That Fall, just before the stock market plunge, he convinced his father to fund a year in Paris to study art. He took rooms in Montparnasse, first on rue Stanislaus and later on rue Mathurin Regnier, both close to the legendary brasseries — la Coupole, le Dôme, and la Rotonde — where Picasso, Hemingway, and Sartre often lingered. He studied nearby at the Académie André Lhôte, formed just a few years earlier by this modernist master; and, at the triumvirate of famous academies: the Académie Julian, the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and the École des Beaux-Arts. He also studied privately with Maurice de Vlaminck. Certainly, the Fauvist’s earlier bold use of color had made an impression on Potter, as did his evolution to an earthy palette possessed of boldly expressive brushwork. He also found his teacher to be an amenable drinking partner. As testament to their friendship Vlaminck gave him a painting and it hung in Potter’s home for many years.

Potter’s year in Paris was a romantic one, too. This passage from his hand-written Book III paints a cinematographic atmosphere:

“Lost from people: I left, first trip away….Montparnasse.

In the train station, Mae ran. The window framed her running as the train moved toward daylight out of the station.

As I looked out, the aisles between tracks receded from the window.

Her running along beside the train gave an effect of her being suspended, wiggling like a thin doll shaken. Her boldness and frailty, her flowing clothes while she ran through the cold Paris air of that metallic station platform faded gradually into gloom as the distance increased between her and my face at the window. Finally, daylight beyond the station roof blotted the vision out. I remember being very aware of me as a traveling person, separated from a bond; breathing independently. Little did I know the real meaning of the running.

When I returned three days later she was not at the station to meet together as planned. She was not at our studio. There were two empty wine glasses and a pack of cards on the little table. Mae had gone back to cocaine and alcohol. Later, I was told, and she told me, that she was wandering the streets dazed. Her pallor and vagueness gave the impression of her being very far away beyond reach.”

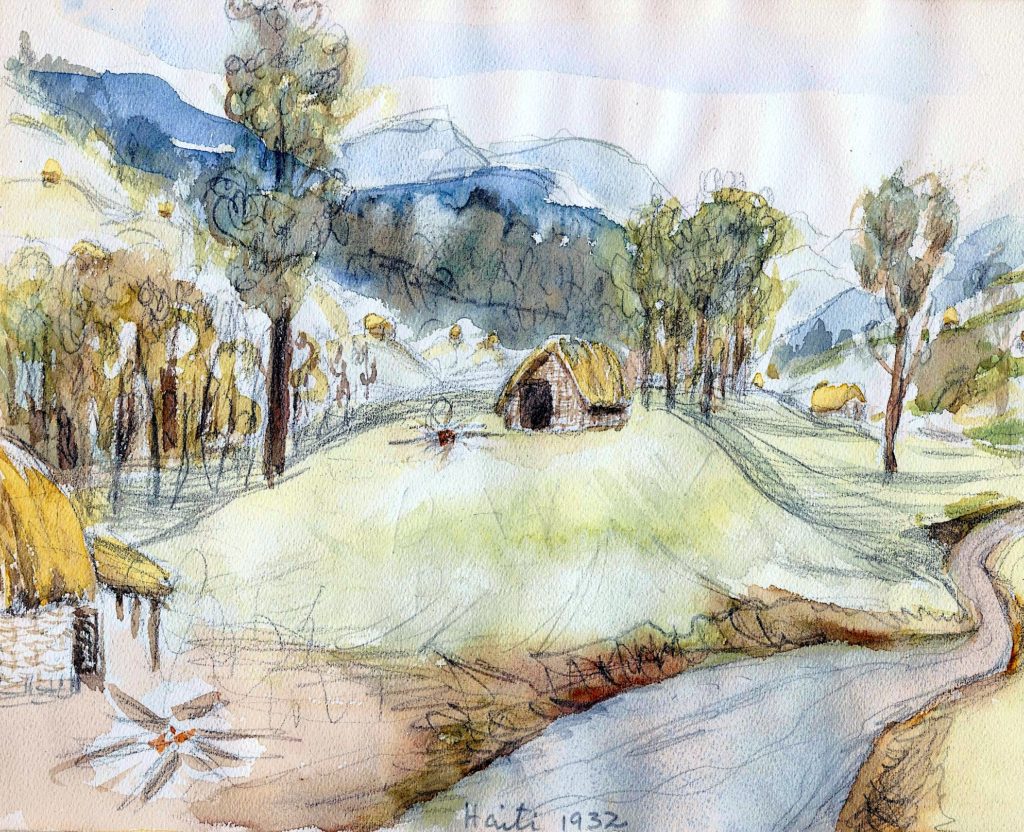

Potter returned to New York in the Fall of 1930, took a studio on a top floor on 36th Street, and began two years of study at the Art Students League under Walt Kuhn. In 1931, wanderlust brought him to Haiti and he settled along the far western coast near the isolated town of Jérémie. There he built a wattle and daub thatched hut of African design as his studio. It was here that he began exploring the metaphysical in painting. For example, he described one of his minimalist abstract paintings — composed of three bold strokes — as a “pictorial memory” whereby the brown stroke represented the earth; the blue stroke “the deep azure blue of night;” and the pink stroke “the floating high-up wisp of cloud.” Although that painting was never located, one would have been tempted to compare its structure with that of Rothko’s mature stacking of three rectangular color fields produced twenty years later. As Potter’s description continues, it shows that he at least shared with Rothko a deep spiritual immersion in his approach to painting.

“Which is more real,” he wrote, “the living experience – the three painted brushstrokes – or the words describing them? Three sorts of consciousness. All the same? Verbal and paint reminders. The original sight was a more living experience. Paint and words reminders. But the poetry of the original sight rang an interior bell, chord. The ‘Yes, I know’ déja vu was waiting there already.”

Potter returned to Haiti in 1932, this time taking a small house in Pétionville in the hills just south of Port-au-Prince. Peripatetic by nature, it was also in 1931–32 when he roamed about the Northeast painting in the prevalent style of regionalism. One of his summer studios was in a cow barn in Bedford Hills, New York. He spent another summer in the village of Heath, Massachusetts, on the Vermont border. In 1932 he established a studio in East Harlem and secured his first gallery representation, at the Marie Harriman Gallery on 57th Street — a success he credited to Walt Kuhn, the gallery’s only American artist.

In 1933, at twenty-three, Potter felt the weight of the Great Depression as it rolled on its ominous path through America. His reaction was to embark on an adventure that would last five years. He bought an old Rolls Royce convertible for its scrap value of $75 and drove south to the poorest region of the country: Appalachia. By the time he got to Hartford, Tennessee, its natural beauty compelled him to stop. The small village is nestled within the Great Smoky Mountains and the Cherokee National Forest, near the state’s easternmost border with North Carolina. Today, it is best known for its white water rafting expeditions, but during the Depression the primary source of jobs — logging and the paper mills — had dried up. During the winter months Potter occupied the town’s “Woodsman’s Hall,” turning it into his studio. Mingling with the townsfolk, he sought and befriended many locals who would sit for their portraits, specifically seeking “character types.” Aiming to capture the spirit of both the individual and the times, his approach was to pose them just as he met them, without any props or special dress, gazing directly at him. The roots of his empathy are found in “The Eight,” also known as “The Ashcan School” — that greatly influential group of painters who dominated the American art scene of Potter’s youth in New York and who urged artists to capture the authenticity of everyday life. The most expressive and sensitive of Potter’s portraits show their greatest stylistic affinity with the portraits of Robert Henri and George Luks.

One fateful sitter he had met in town was eighteen-year-old Scott Williamson, who suggested that come springtime the artist should hike west from Hartford, cross the Pigeon River, climb over the mountain, and discover picturesque Cane Holler (Hollow). Potter had already made many hikes up the surrounding mountains to paint landscapes, and he spent those months in his tent. When he made the trek to Cane Holler he set camp there, captivated by the natural beauty of this secluded valley high in the mountains. One day he came upon his young friend and was invited to the Williamson cabin, a rustic board and batten shack. There he met Scott’s mother, a widow who had given birth to fifteen children, eleven of whom survived. All had moved on except for Scott and his two younger sisters. During the next winter Potter felt comfortable enough in his friendship with Scott to suggest that he would abandon his tent that spring if he could move into the family’s three-room cabin. Potter was welcomed, and soon found he belonged to a new family whose members were attracted by his charm, quick humor, and spontaneity.

The youngest sister, Cindy, felt that attraction particularly strongly. Blonde-haired and blue-eyed, shy and pretty, Cindy did not go to high school because it was too far away. A carefree mountain maid, she could have been cast in a movie about the hillbillies of Appalachia. To the delight of the Williamsons, that summer of 1936 saw Cindy — at age fifteen — become Mrs. Fuller Potter. The couple soon moved to New York, where Cindy was warmly welcomed into the family. She became a voracious reader of comic books because this is the medium with which she taught herself to read. Potter took a studio on East 84th Street, and in 1937 at East 83rd Street overlooking the East River.

During their five years together the couple had two children and split their time between Manhattan and a cottage near Hartford, Tennessee, at Trail Holler, not far from Cane Holler. Potter also introduced his young wife to Bedford Hills, where he created a studio in the loft of a barn and added a skylight. He also returned to the village of Heath, Massachusetts, for another summer. In 1938 he painted snow scenes in a studio in Littleton, New Hampshire near the White Mountain National Forest. Unfortunately, he had over the years become even more deeply addicted to Tennessee’s potent “White Mule” whisky. In 1941, after Potter’s “five years farming, painting, and being a school-teaching parent” Cindy divorced him and returned to Tennessee with their children.

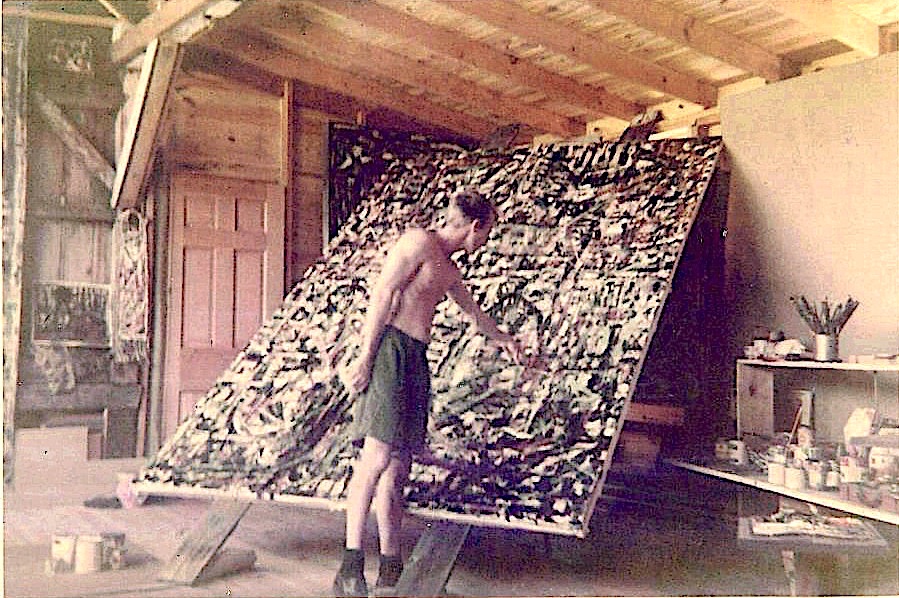

In 1944, while living at his ground floor studio at 232 East 84th Street, Fuller met Alice Otis, also a painter, who was a young curator at the Museum of Modern Art. Alice was also from blue-blood stock, with roots in Virginia, and grew up on East 66th Street. After attending the Brearley School in Manhattan she studied painting at Bennington College in Vermont. She soon proved to be the catalyst for an artistic turning point for Potter. Her first conversation with him was about “The interconnectedness of art, the psychological meanings of different shapes, lines, and designs.”3 Although he had experimented with expressive forms of abstraction since the late 1920s, he was still concentrating on Regionalist landscapes, portraits, and still lives similar to those he had painted in Tennessee. These works had been exhibited in 1942 at Weyhe Gallery, and in 1943 at Schacht Gallery. Newly inspired by his new muse, Alice, the forms and colors of trees, ground, and sky in his landscapes soon began to morph into swirls as if they were dissolving into a landscape by Edvard Munch. At the same time, Potter wrote a treatise, The Meaning of Art, steeped in the metaphysics that would permeate his work for the rest of his life. By 1944 he had completely committed himself to abstract expressionism and by 1945 he had expanded his reach to very large oils.

Alice and Fuller married in 1945 and divided their time between the East 84th Street studio and a barn in Salem, Connecticut. Within four years they had three children. Yet the painter’s alcoholism raged unabated. One account by his brother, the writer, Jeffrey Potter, illustrates the extent of the problem, which peaked in the summer of 1948:

“By the mid 1940s Fuller was producing larger paintings, and felt the need for a much larger studio space. So, he rented a storefront on East 84th Street between Second and Third Avenues. Parked out front was his large U.S. Army Communications truck that he had purchased at a surplus bargain. By this time his family had grown to include three young children, so he outfitted the truck with bunks for family excursions. Driving with Fuller was hair-raising even without his being drunk. But late one summer evening, Fuller jumped in his truck, completely drunk. As he accelerated down Second Avenue, he suddenly decided to turn up 81st Street. As he did so, he took the corner so widely that he crashed into the front steps of a brownstone. The truck’s stair railings were impaled across the grill and fenders. Fuller simply crept to the back of his truck, got into one of the bunks, pulled a blanket over himself, and pretended to be asleep. Minutes later, a policeman pushed the blanket off of Fuller with his nightstick. Still in a drunken stupor, Fuller strongly resisted the cops and was thrown in jail. The next day he stood before the judge. I had never seen him so sad and embarrassed.”

Potter later described the event as owing to “The voice that schizoid personality hears say, ‘throw your shoes out the window of the police car, and your coat, and all your clothes!’ This was God talking to an alcoholic in delirium.”

Remarkably, it was not this truck crash that compelled Potter join Alcoholics Anonymous. Another, more frightening encounter, provided that spark about a month later in 1948. Potter’s brother, who summered in Amagansett, Long Island, and had increasingly been impressed by the way in which his brother’s paintings had been evolving for several years. So, he suggested that his brother come to Amagansett to meet a neighbor and friend named Jackson Pollock. In 1985, Jeffery wrote the first biography on Jackson Pollock, and it was used as the basis for the movie. He described the event:

“One evening, Fuller came over to our place for a drink with Jackson. Considering Jackson’s difficult personality, I was surprised that they hit it off so well, and Jackson even invited Fuller to see his paintings in his barn. Pollock rarely made such invitations. Well, Fuller returned to our home at 4:00 the next morning, drunk and exhausted. Later, he said that while he was exhilarated by Jackson’s paintings, he was terrified because he had also confronted his demons. That was the incident that made Fuller join A.A.”

Potter knew other alcoholic artists, but the result of this encounter was quite different. This time, he could not sleep off the profound distress of his convergence with Pollock. Emotionally and physically, he was exhausted. He had felt a persistent negative aura about Pollock — the way he could drain energy from those around him. It was as if Potter was looking in a mirror, had a premonition of Pollock’s fate, and became terrified. He chose to never visit Pollock again. Instead, this emotional collision compelled him to join A.A. The incident may have equally frightened Pollock, because this was the Fall when he, too, would quit drinking. Whereas Pollock was able to stay sober for about a year, Potter remained committed. Both men had come face-to-face with the same demons that night. But the difference between them was that Potter was not only able to recognize those demons of addiction but fully divert their energies into his art lest they killed him. In 1948 he wrote, “Art, then, might be, in its highest forms a signpost, an emotional road map of the states of mind.”

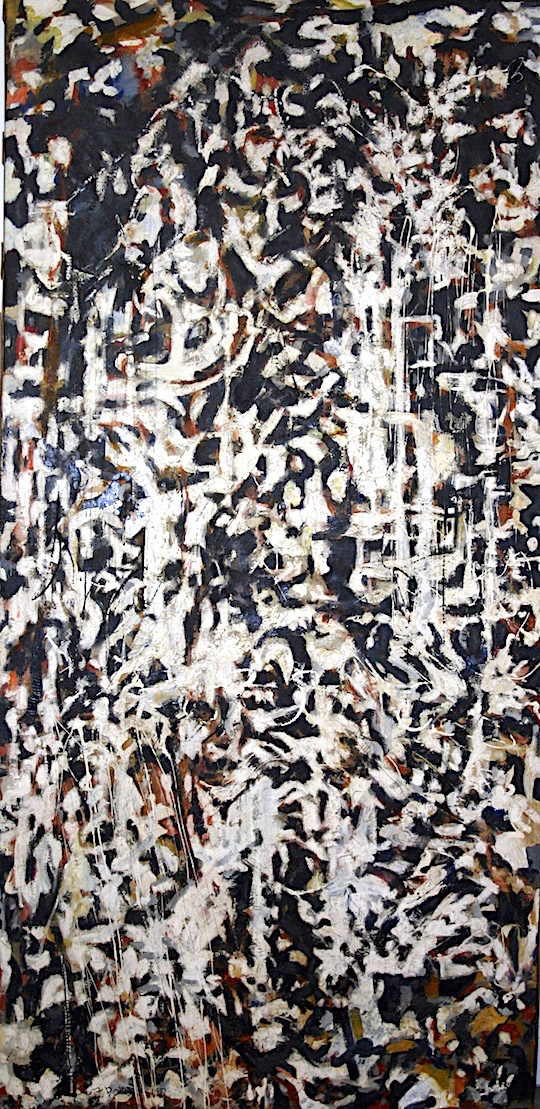

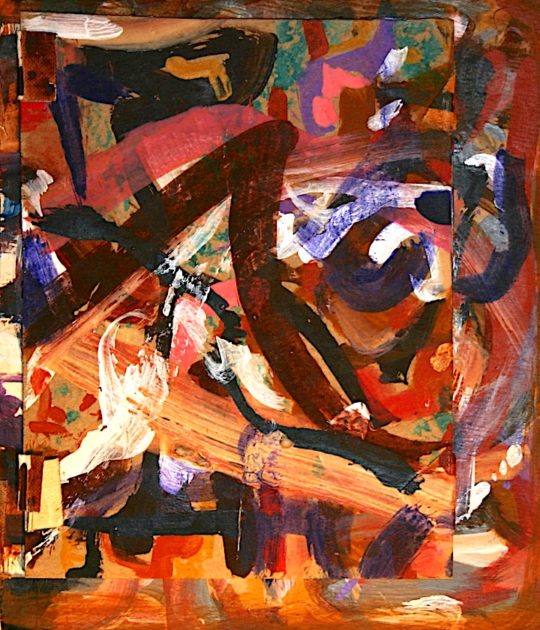

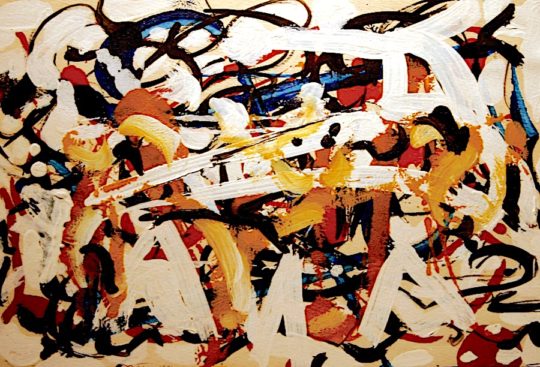

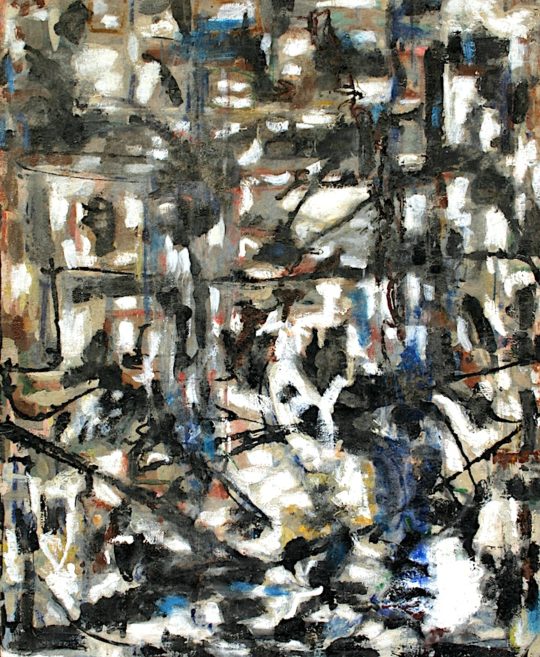

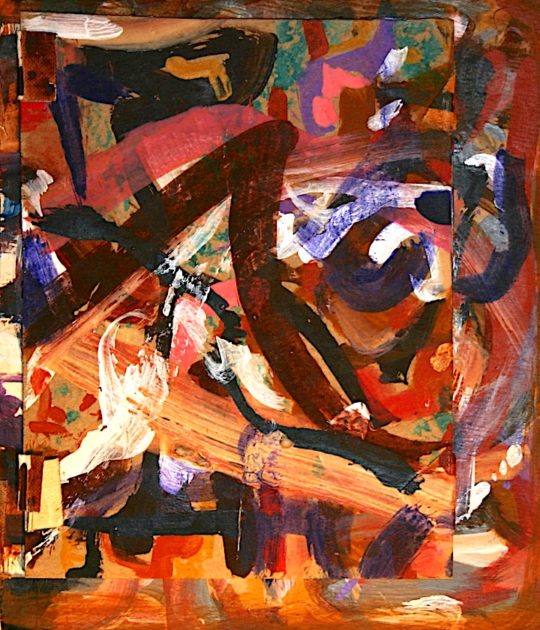

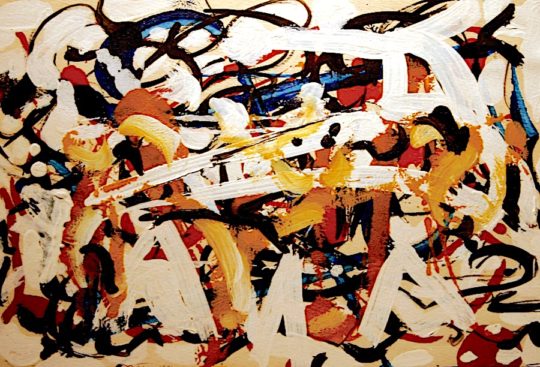

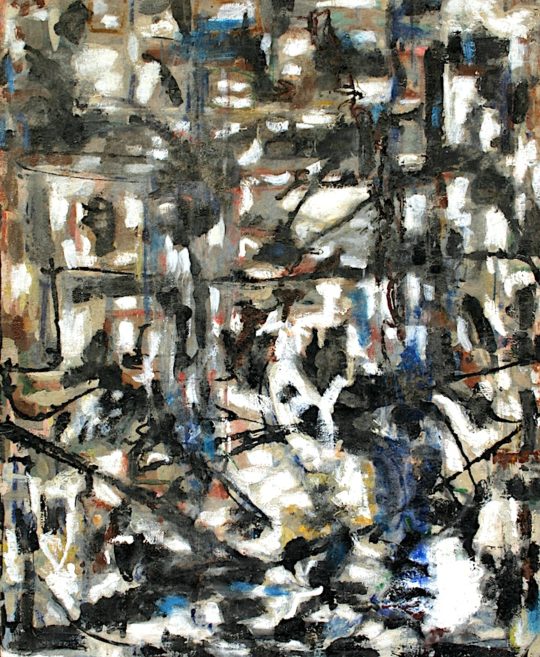

Potter’s new paintings had attracted Ferargil Gallery on 57th Street in 1945 and they represented him for the next five years. In 1949 a critic for ArtNews, Stuart Preston, noted “the weight of his expressive technique and the range of his rich, rusty colors.”4 The rusty colors to which Preston referred were burnt umber, red oxide, raw sienna, burnt orange. His palette — which also prominently included black, white, and yellow ochre — would remain consistent throughout his life even though he later added brighter primary colors as accents. Evidence for Potter’s inspiration could be found in his home where he hung a magnificent carved and painted wooden shield from New Guinea’s Upper Sepik River region. In both color and form his brush marks he continued to pay homage to this tribal culture. In addition, his brushstrokes for each painting were often of similar width and seem to pulsate, as if he were a playing with the same musical instrument throughout the opus. In some paintings the blacks serve as borders to accentuate color, creating an effect similar to that of stained glass.

From this point onward, Potter was bursting with creative energy. He also needed a change. In 1950 he and Alice bought a forty-acre farm in Ledyard, Connecticut, with a home built in 1751. The chicken coop was enlarged to become a studio. He called himself a “New Husband” and immediately embarked with his family on extended artistic adventures abroad. In 1952 he returned to Paris, taking a studio in the Val-de-Grâce area of Montparnasse. Beginning in 1953 he was represented by Stuttman Gallery on the Upper East Side. That year the artist made an extended stay to paint in Cuernevacca, Mexico. And in 1955, he rented a garage studio in Rome. He exhibited at the Circolo Artistico Internazionale on via Margutta and mingled with emerging musicians and artists. This small street in the center of Rome had also become home to Federico Fellini.

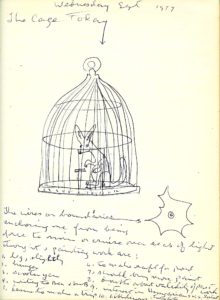

Potter’s long bouts with alcoholism had brought nearly a decade hiatus to his writing but he resumed in 1957, beginning a second thesis entitled, Nettles in Fifty-Seven and Fifty-Eight. That summer, he made lists of “nettles” that needed to be eliminated from his life so that he would be clear to focus upon his art. One nettle, which was the necessity of securing a gallery exhibition, caused him to illustrate himself as a mouse in a cage. He wrote, “Act like a mouse when pursued. Try here, give up. Try there, give up.

Try another place, quit. Try again half-heartedly. Next thing you know, you have escaped to the sea of true labor.” Certainly, the collective family wealth inherited by both Potter and his wife allowed him to paint in peace on his farm, entirely eliminating the need of landing a gallery. But in 1957-58 he summarized the persistent “nettle” that he and all artists face: “Fear of inadequacy in art. Fear of neglect as a painter. Fear of being deserted. Terror of being found penniless.” In addition, Pollock’s death by car crash just a year earlier likely weighed upon him as he reflected upon their fateful encounter.

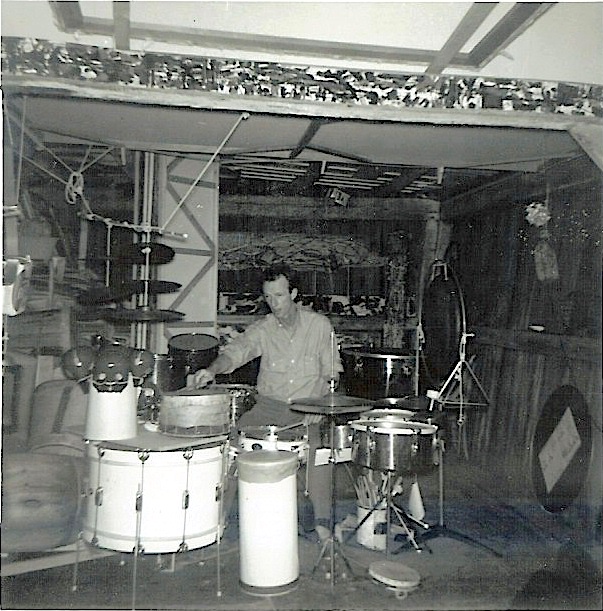

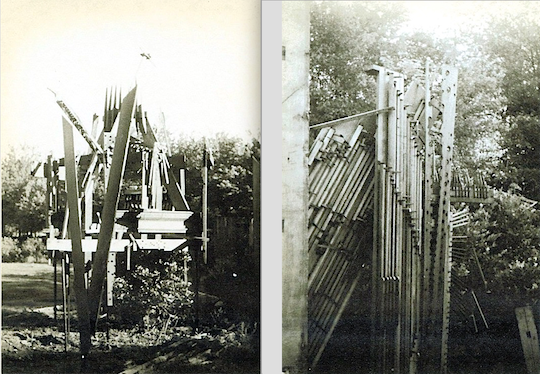

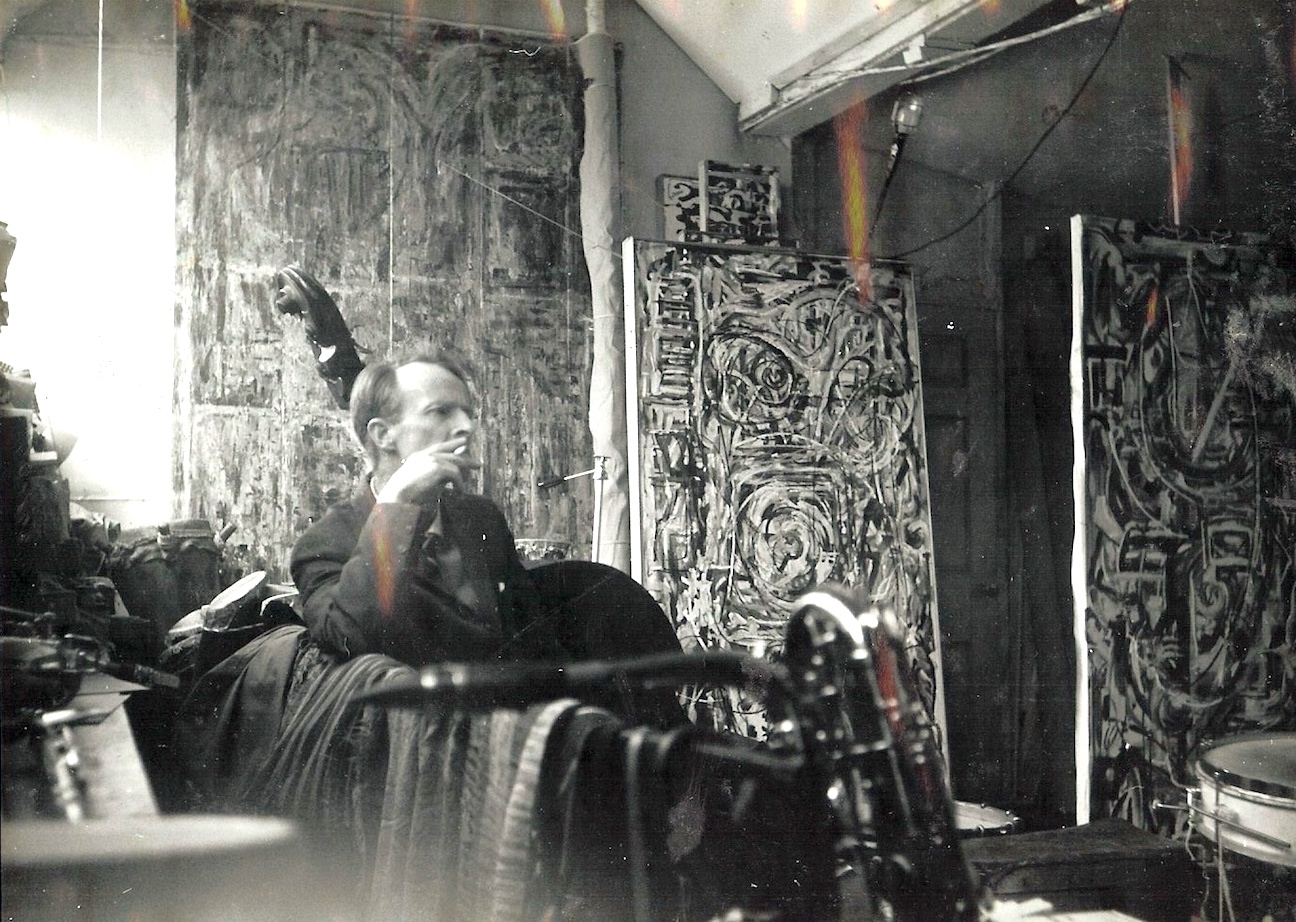

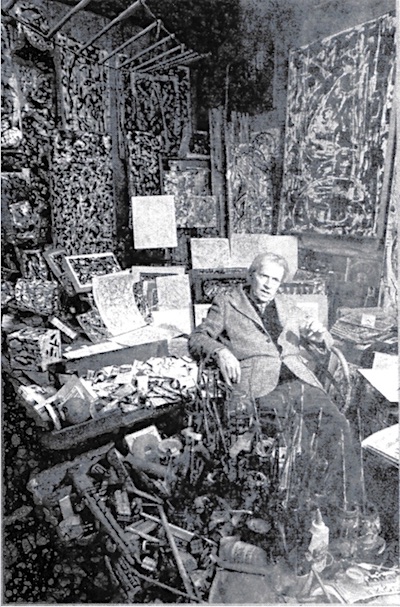

While music had always been an important part of Potter’s life, it now became fully integrated with his making of art. He played many traditional musical instruments — drums, bass violin, and French horn, to name a few — and now invented large and elaborate new music-making machines made from cans, bottles, wires, tubing, and other found objects. These were set up outside his studio, and looked like improbable Rube Goldberg inventions, operated by hammers, hand-cranks, or even by the wind. His monumental sculptures were erected on the farm’s fields while smaller pieces could be discovered hidden in the surrounding woods and hanging in the trees. In describing the “Panic of Nettles,” he wrote, “What should be an interest, such as drumming, becomes an enthusiasm, even an obsession with me. Skipping lunch, short on sleep, tenser & tenser. Making drums, buying drums, playing drums. Mad practice — no time for breathing, wife, eating, sleeping, relaxing, and on and on.” Potter’s art “happenings” of 1957 were coincidental with Allan Kaprow’s coining of the term that year.

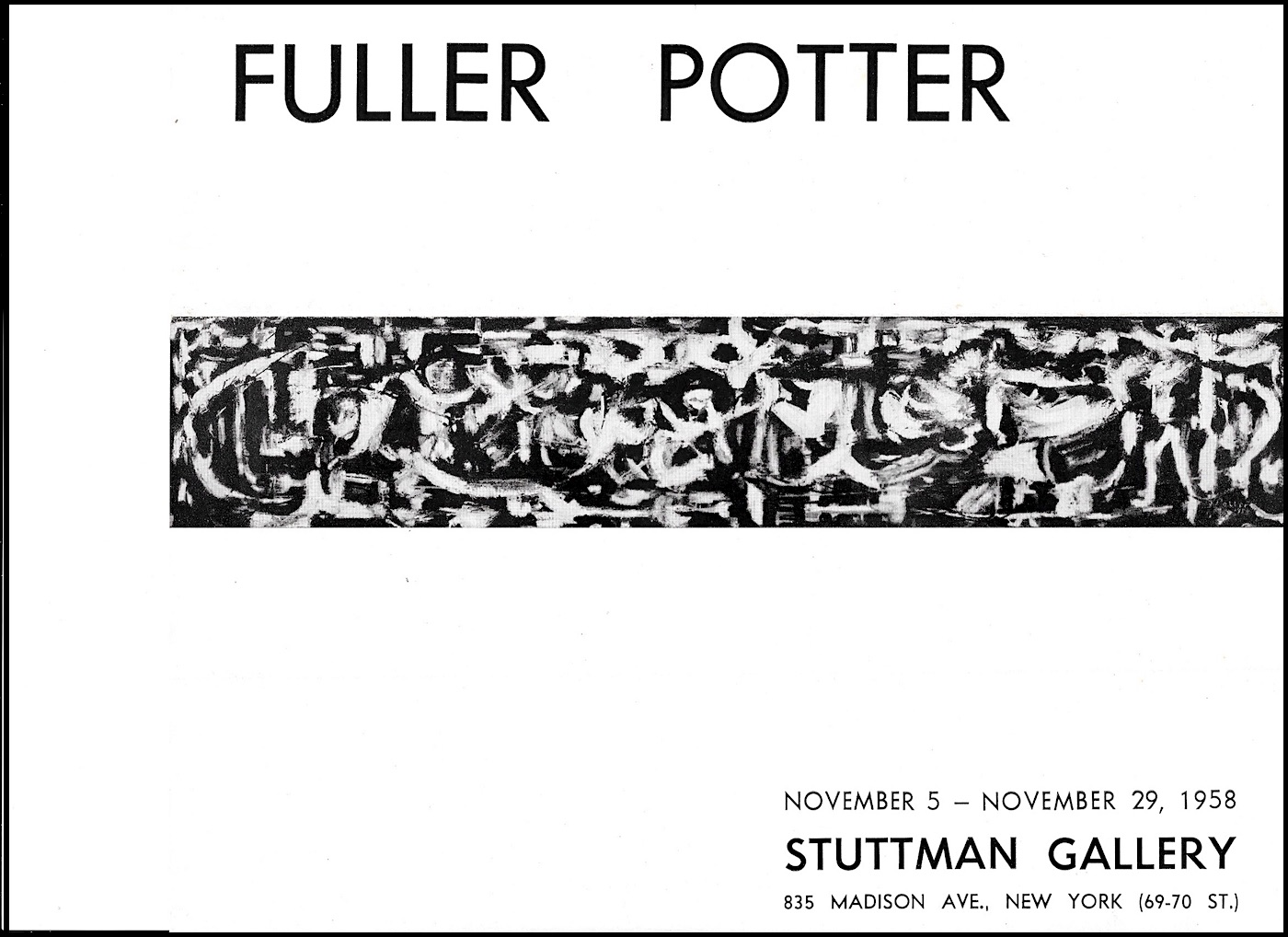

In 1958, Potter ended “seven years rest from gallery exhibiting” with a solo exhibition at Stuttman Gallery at 835 Madison Avenue. An art critic for the New York Times, wrote, “Fuller Potter’s oils at the Stuttman Gallery register more sensitively the pulse and regularity of the artist’s brush gestures. Animated, sober in color… appeal to the visual, can be admired for the deftness with which it is applied.” However, once having secured this exhibition Potter may well have come to realize that all of the “nettles” leading up to it were ultimately self-imposed. He acknowledged that the Abstract Expressionists were the avant-garde who had won the war over Paris in making New York the new art capital of the world, but he lamented the fact that the School of Paris was still winning in actual sales. Potter had stuck in his notebook an article from the New York Times that stated that while the 1953 annual exhibition of the École de Paris held at the Galerie Charpentier drew 25,000 people to pay an admission fee, by 1957 that number had risen to 86,000 people — and the entrance fee was equivalent to the cost of theatre tickets!

Whether Potter thought he had achieved a Pyrrhic victory with his solo exhibition at the Stuttman Gallery, or whether he had simply eliminated an annoying “nettle,” any concept of dependency upon a gallery was now gone forever. This would be his last this exhibition. He now felt he could resume putting his full energies into the pure act of making art and ignore the burden of New York’s promotional necessities. His journals show his “to do” lists, which were tasks that held for him the highest priorities. A list for a typical day would be to start new paintings or sculpture; feed and walk his pet pig, Pearl; weed the garden; repair the boats; repair the dams; go swimming; fix his motorcycle; visit the Museum of Natural History; and, have libidinous thoughts. His writing also became more philosophical, exploring not only the critical importance of creating art but of existential matters. In 1958, he wrote: “Were I to have more faith in and familiarity with the Eternal Muses, might I not find that there is an intergalactic aesthetic reality to be espoused? Not the latest artist arrival on the current of popularity & esteem, but the spaceman of all time. Great comfort would be in belonging to the vast company of an interstellar artists’ mind world.”

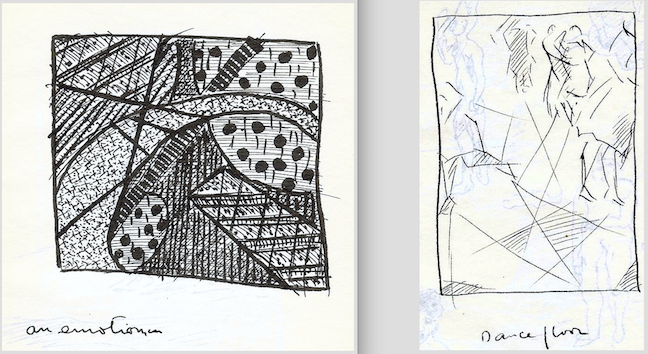

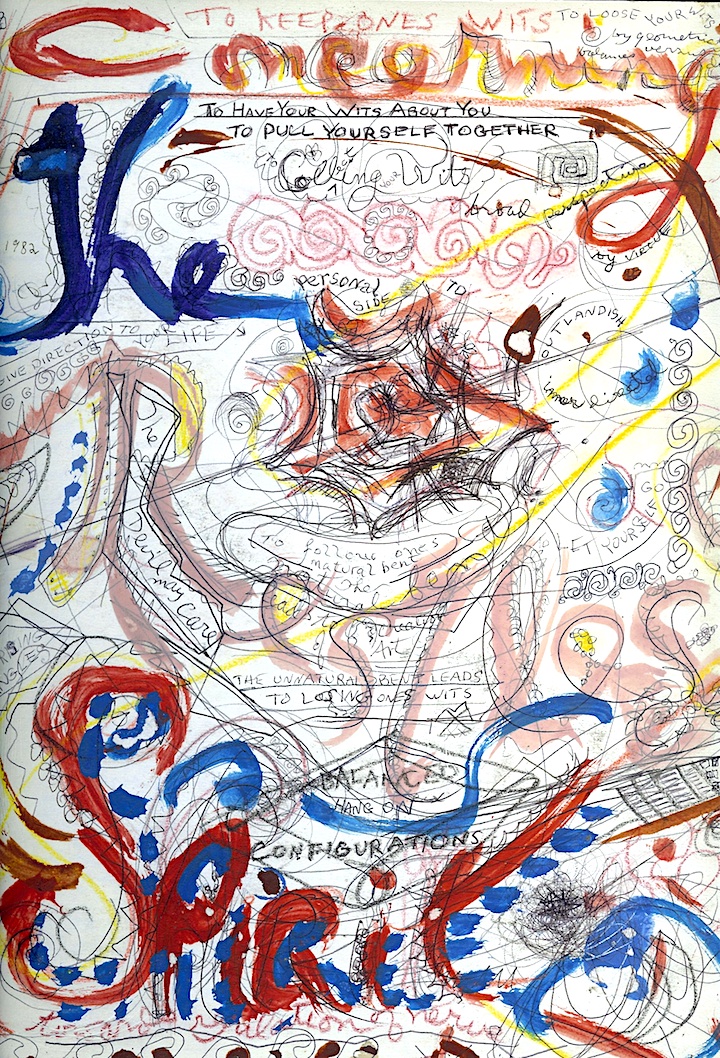

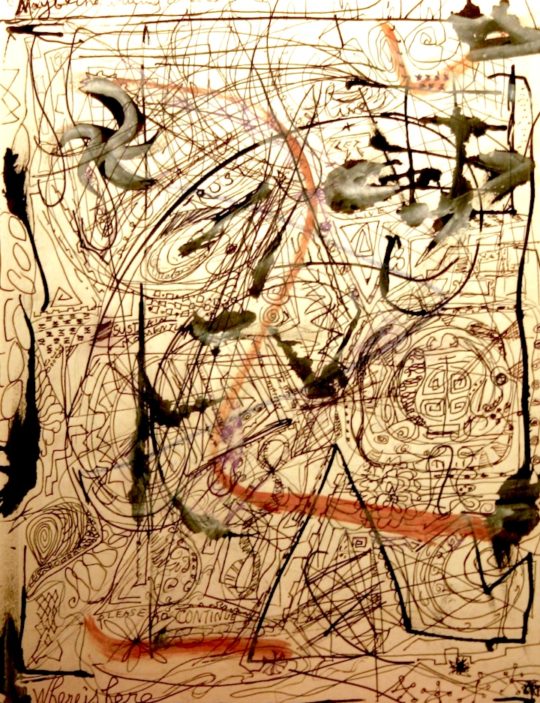

Potter continued his sojourns in Paris, where he helped found a branch of Alcoholics Anonymous. In 1968 he returned to Rome, taking a studio on the via Panama at the southern edge of one of the city’s largest parks, the Villa Ada. It was also in 1968 when he resumed regularly writing his notebooks. He called this third series, from 1968–1978, Concerning the Restless Spirit… a two-part book that included The Art Side. He introduced them by saying that “Notebooks are for sorting out thoughts and to record them for future use in finding one’s way.” Indeed, he returned to his notebooks frequently, often correcting, clarifying, or adding notes from previous years. Almost always, he sketched images between and over his handwriting, the words becoming fused as essential parts of the final image.

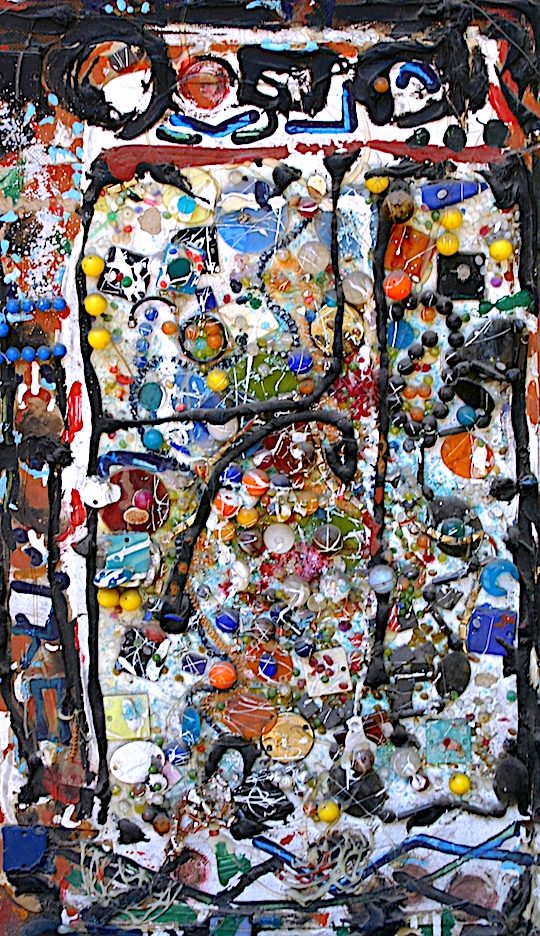

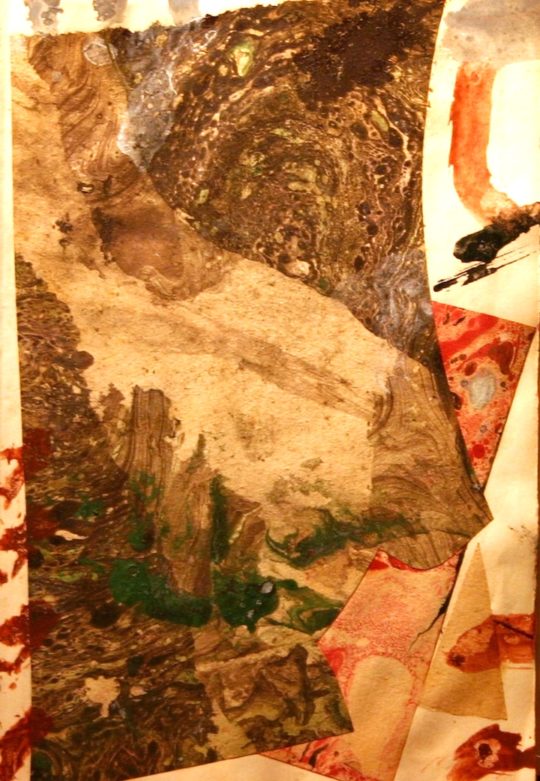

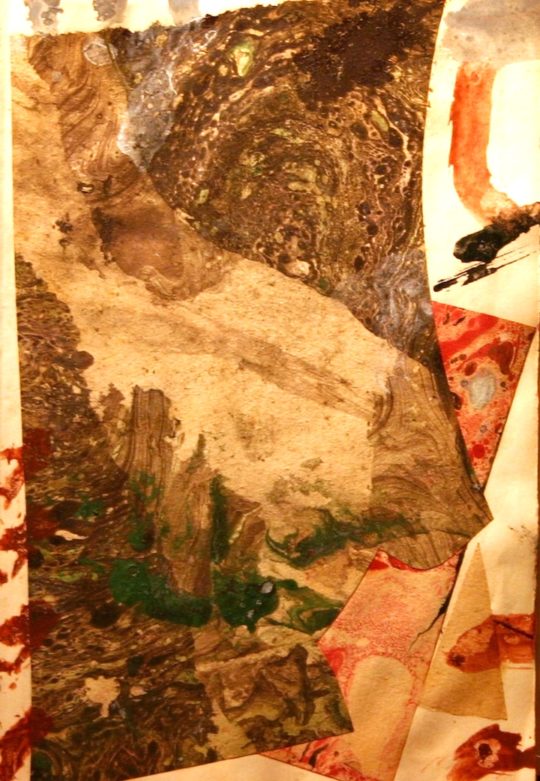

During the 1960s, Potter continued his practice of painting with various music genres blaring. His brushstrokes are typically calligraphic, centrifugal rhythms of spirals and helixes. Sometimes he even used the paint tube as an instrument, squeezing the pigments directly onto the canvas in big swirls. His arabesque shapes and French curves prefigure Frank Stella’s work from the late 1970s–early 1980s. In both drawing and painting, Potter’s spontaneous and highly personal “scrabble of marks” were always intended to form symbols for emotions, objects, and relationships — keeping him strongly rooted in the Surrealist doctrine of automatic drawing. Indeed, it is in his drawings where one finds the surfaces completely covered in laceworks of pen lines, allowing him to more clearly express his personal symbols. By 1970 he had expanded his repertoire of mediums to include marbles, plastic beads, twigs, sand, and other found objects — all rhythmically placed as forms, with colors acting as emotional agents. Some paintings are heavily worked, composed of layers of oils on cardboard, layered upon each other, as collage.

In 1972 Potter bought the Old Mystic Baptist Church. “It seemed like a shame to see a beautiful spacious old building standing idle waiting to be torn down….so I decided to buy it for myself and others to enjoy.”5 He conducted classes in life drawing, block printing, ceramics, mosaics, and textile design. He scheduled Guru Maharaj Ji as a speaker, the fourteen-year-old Indian phenomenon, avatar, and leader of the Divine Light Mission. Potter also made plans for encounter groups, primal scream therapy, and workshops in psychodrama. Local critics fiercely opposed his programs implying that his group was nothing but empty-headed guru-worshippers. “There were rumors of nudity, and neighbors were suspicious of the artist, with the odd name and scraggly blond hair who bought the Baptist church.”6 The caricature of Potter created by the press was so caustic as to incite one of his defenders to accuse the newspaper of yellow journalism. Despite a battery of friends who rallied to help Potter’s cause, the town won the battle on a technicality: Its inspector condemned the building as unsafe. Asked by a reporter if he would conform with the building code, Potter turned the conversation to gurus and meditation. Ultimately, he had no choice but to sell the church.

By 1977, Potter had rented a huge two-story ballroom in Mystic as a studio for creating pioneering videos that featured his sculptures and large paintings as stage props. “The videos,” he wrote, “were attempts to talk with intelligible words, while painting, about design meanings through varied demonstrations. The tail wagged the dog, as people acting out design were stronger as personalities than the interest of the ideas.”

Potter was essentially an epistemologist drawing from his toolbox that included painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry, dancing, singing, and writing to both probe and express his art consciousness. He called the creative process “Paint-Thinking,” which was for him as natural a necessity as eating or breathing. “Living through my day could follow the same intuitive-trusting technique. Feel one’s way, judge later, it’s worth later….Let’s try to say that art is as part of our being as is breathing. That art is a synthesis of thinking and expression of feeling.” Like Picasso, he examined and was influenced by man’s earliest marks, from cave drawings to the artifacts of non-literate tribes. He also closely observed a dancer’s physical movement in space and a musician’s tempo in order to get a better grasp on abstract painting. He described “the solid earth upon which stage we do our acting in the air medium” and “exposing ourselves by marks we posit action-shapes and gesture-shapes on the ground and in the space.” He called the process of looking at a painting “Look-Knowing,” and listening to music as “Hear-Music-Being” and described both as valid forms of consciousness, independent of words. Conversations between people, he contended, brought about “a different sort of knowing.”

It was because Potter possessed a solid confidence and trust in his artistic expressions that he could become fully satisfied living in relative isolation on a farm remote from Manhattan. As soon as he realized that his being pivoted about an immersion in art, those past concerns about pursuing galleries and museums lost their grip. “Where one becomes aware that a particular action is real — really real — is what one is. This happens day after day when I find that HERE I AM PAINTING, where I discover working in paint to be the most real Being….The point I endeavor to rise to in these writings is that AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE IS THE MIRROR where we see our own inner living structure with eyesight interpretation by seem-alike (matching) symbols.”

It is equally important to note that Potter recorded many humorous exchanges with his wife, Alice, who always brought him down to earth. By his sixties, he would often contemplate his mortality and regret not having expended the energy to have sought more attention for his paintings. When he told Alice that he took pride in playing the role of the “Dying Swan,” which was intended to draw sympathy and attention, she quickly corrected his act as being that of the “Ugly Duckling.” When he told her he wanted his epitaph to read, “Here Lies an Enemy of Self-Righteousness,” she immediately replied, “I think it sounds self-righteous.” As one who was notorious for his attraction to women, he explained to Alice, “The more I love others, the more thee I love;” and, he concluded, “You can put that on my tombstone.” Alice replied, “Fuller, I’m not giving you a tombstone…You’re going to be the only person at your funeral.”

The fourth of Potter’s journals covers the period 1978–1982, increasingly filled with layers of hand-written script, sketches, and more complete designs for paintings. He often retuned to earlier pages and, reconsidering his past thoughts, made corrections so that his deeper art consciousness could better “operate in paint.” He often referred to himself in the third person, as if this distancing technique would allow him to become even more objective and analytic about his writings. In what he referred to as “an eruption of obsessive thinking” he delved deeper into metaphysics and Freudian psychology. While Pollock was interested in the theories of the unconscious put forth by Freud and Jung, Potter was more interested in those unseen energies that powered the universe behind our field of vision. He regarded the eye as a vehicle where the inner and outer worlds could converge. He wanted to explore, for example, how the spontaneous injection of arabesque shapes into a painting could generate the sympathetic centrifugal rhythms he found in music, dance, and poetry. And in the process of this daily pursuit, he felt he would discover the roles of colors and symbols as emotional agents. In his “Blank Wall Assumption” he postulated that our sensory memory (tactile, visual, auditory, smell, and taste) is drawn on a blank wall, beyond which lies “the true material of our basic thinking process.” He emphasized that in our pre-natal state of existence, there is a “vague realm of pre-memory” where instinct automatically operates, being:

“1) growing; 2) moving; 3) nursing; 4) sleeping; 5) waking; 6) breathing; 7) crying; 8) peeing; 9) bowel movements; 10) and eye opening and shutting… The meaning of these inner ten within earthly reality is where we come to grips with art forms, and still experience in living even though they are not now what they were when first experienced because they have receded behind the WALL. The frictions between us and the world outside as experienced, felt, and remembered is what art means. Art is not what we talk about, but is our way of talking.”

Therefore, abstract expressionism was for Potter a language spoken only by learning how to access the other side of the wall “where the basic building blocks of consciousness lie obscured in code familiar to instinctual sensibility.” It was only his absolute trust in intuition, which he referred to as “a set of secret gears” in his head, that assured the integrity of his works. Every brushstroke and every shape had a purpose. Even as an avid reader of Scientific American, he was interested in forces in space that one can’t see. In 1978, as he continued to plunge into visual explorations he continued to ask: “Why a square? Why the circle? Why the straight line? Why repeated identicals? Why are light and dark contrasts, black and white, such a thrill? And stripes or parallels? These are BURNING questions. They are HAMMERING at my MIND. Stinging my consciousness. Pulling at the fabric of my intellect. Yanking and banging on my intelligence. Nagging at my thoughts and bearing at my understanding since 1945, for 33 years. Like baby’s frown at birth – puzzled, furious, shouting, crying hard.”

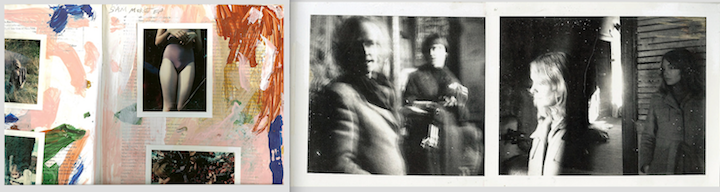

By 1980, Potter viewed his journals as travelogues through an artist’s mind and called his paintings “graphic patterns of enlightenment.” His large paintings continued to be accompanied by extensive explorations of musical sounds, Polaroid photographs of superimposed images, videos, 8-millimeter films, and performances of poetry. He also began to create a new kind of art book, being a sequence of abstract paintings on cardboard, bound between covers that were themselves abstract paintings. He referred to this series of books as “interior explorations” where the abstract drawings “show distilled experiences between covers…The collected life of inquiries memorized. Laid out before your eyes.”

When Jeffrey Potter was writing his biography on Pollock in the early 1980s he interviewed his brother, Fuller, about his fateful encounter with Pollock in 1948. Jeffrey recalled his brother’s quote: “I thought the guy was crazy. And when he took me out to the barn I thought the work was crazy — but out of it came poetry. In Pollock’s work the paint is talking… When you’re painting with the rational mind and your work pretends to scream, it is nothing. But the great Pollocks are screaming; they are rich and wonderful. So he upped and died.” Later, in an interview with National Public Radio about his book, Jeffrey said that it was his brother, Fuller, who best expressed the essence of Pollock’s drive to paint. He understood his brother’s need to talk about the emotions that come through paintings. And he said that Fuller recounted that it was through abstraction expressionism that Pollock “was unconsciously offering us some of his own agony, some of his own excitement, and perhaps some of his own fantasies…I think you can say of a painting that it is a language, particularly of abstract painting.”

By 1989, Potter was possessed of a heightened awareness of his mortality. In July, he wrote:

Lost all morning

Mentally

Until just now looking

At strange abstracts done ten years ago

BANG

Restored to sanity

Field of paints is life saver

Bright organized state of mind

Before it was mosquito bite irritation

Horror at seeing left leg’s blue areas of veins

Deaths face staring

Angels now cheering me on

Not worry about personal form

Prestige

Applause

The sparking effervescence Fuller sees

In a late small abstract completed last month

Why go on trying to worry

Unfair to oneself

On April 4th, he wrote about the various ways he could leave this life:

Potter plans exit from this world:

1. Jump out of speeding car

2. Off cliff somewhere

3. overboard Block Island ferry

4. many pills to sleep

5. drown choked

6. decapitated at railroad track [by] train

7. starve in bed

8. germs in head

9. run over by tractor-trailer truck

10. out of airplane

11. hang-glider crash

On May 17th, 1990, Fuller Potter quietly left the hospital in Westerly, Rhode Island, and joined “the vast company of an interstellar artists’ mind world” where he would continue to revel in “an intergalactic aesthetic reality.” He had painted every day up to three days before he died.

Postscript

A video taken during the “Buy or Burn” event shows a pile of Fuller’s art being consumed by flames. Fortunately, about two-thirds of the works were sold or given away. His son Dan used some of the proceeds to build what he called “the temple” to preserve the rest of the oils, watercolors, drawings — including the art books, Polaroids, and numerous diary-sketchbooks. Fuller Potter anticipated this future reader of his dairies, introducing his books in one of the volumes:

The Artist’s studio contains recorded

Traveling by Art Books through the mind.

Trips through the mind. Interior explorations.

Abstract after abstract drawings that show

distilled experiences between covers.

Books, books.

The collected life of inquiries memorized.

Laid out before your eyes.

Today, Fuller’s sculptures remain in the fields around his studio and hang from the trees, as do his numerous homemade musical instruments, now rusted victims of the harsh New England elements. They are testaments to his enduring creative spirit. His canvases and works on paper made clear that the lines, shapes, and marks he made sprang from spiritual roots as unconscious symbols of emotions, objects, and relationships. One of his notebook entries stated, “Intellectualizing is a pain. I am looking for graphic patterns of enlightenment.” This authenticity — and a prodigious body of work consistently marked by innovation — conclusively attest to the validity of Potter’s place within the pantheon of significant Abstract Expressionists.

— Peter Hastings Falk, 2017

Acknowledgements

The author is most grateful to Fuller Potter for being one of those rare artists who was also such a dedicated writer, leaving volumes of writings and notebooks. Nothing could be more valid testimony than the artist’s own words about his about his life and art. Artists who have passed on without expressing and recording their philosophy and describing their pursuit of art always risk being misinterpreted by later historians.

I greatly appreciated the many interviews given by Potter’s family and friends from 2004–2015. In particular, his son Dan Potter — a sculptor, ceramicist, painter, and brilliant puppet “magician” of Mystic Paper Beasts — kindly granted many meetings.

Fuller Potter’s brother, and Pollock’s first biographer, Jeffery Potter [1918–2012], generously gave his time in several interviews. His 1986 interview with National Public Radio on “All Things Considered” expressed the essence of both Pollock’s and Potter’s paintings.

Fuller Potter’s daughter Mary Barton Goodman was also a source of illuminating stories about her artist father.

Elaine Mills is an illustrator who was very close to the artist. From 1975–1990 she catalogued his collection, arranged sales for him, and made a series of videos of him in the process of making art, in some cases describing his intentions and feelings. Her most moving video was shot just three months before his death.

Footnotes

1 McGinley, Lisa. “Ledyard Artist’s Son Redefines ‘Fire Sale’” The New London Day, 2 July 1999, p.D6; and, Pearson, Dan. “From Art to Ashes,” The New London Day, 4 July 1999, p.C1

2 Kleber Hall [1882–ca.1946] was born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and lived in West Somerville, Massachusetts. In addition to being a painter, sculptor, and etcher he was also a musician who in his youth played on coastal steamers traveling about Long Island Sound. He taught art at two private schools for boys in Massachusetts: St. Mark’s School and Groton School. In addition to Fuller Potter counting among his students (at Groton), at St. Mark’s he taught George A. Weymouth [1936–2016] who painted realist landscapes and portraits in the Brandywine valley. Kleber Hall illustrated A Quaker Girl From Nantucket (1925). In 1928, the etcher Henry Emerson Tuttle [1890–1946] wrote “The Etchings of Kleber Hall” for The Print Connoisseur.

3 obituary in The New London Day; 24 September 1996, p.B4

4 Preston, Stuart. “Portraits, Still Lifes, Landscapes” ArtNews, February 1949, p.48

5 The Groton News, 10 March 1973, p.17

6 Artist, Town Clash on Building” New London Day, 24 March 1973, p.17

Inside An Interstellar Artist’s Mind World

-

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf Portrait, 1954

45 x 57.5 inches (114.3 x 146.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

8.5 x 5 inches (21.59 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

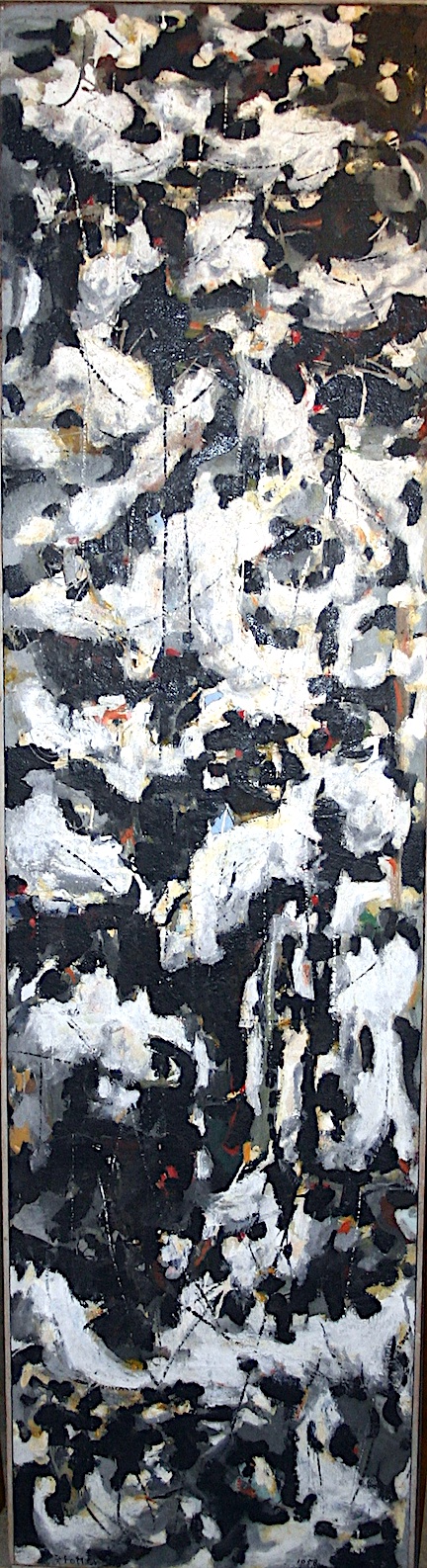

DETAILSUntitled, 1970

42 x 20 inches (106.68 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

14 x 9 inches (35.56 x 22.86 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

11 x 8 inches (27.94 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

9.5 x 12 inches (24.13 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

9.5 x 8.5 inches (24.13 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

9.5 x 8.5 inches (24.13 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

10 x 11 inches (25.4 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

15.5 x 11 inches (39.37 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

8.5 x 5 inches (21.59 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

8.5 x 5 inches (21.59 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

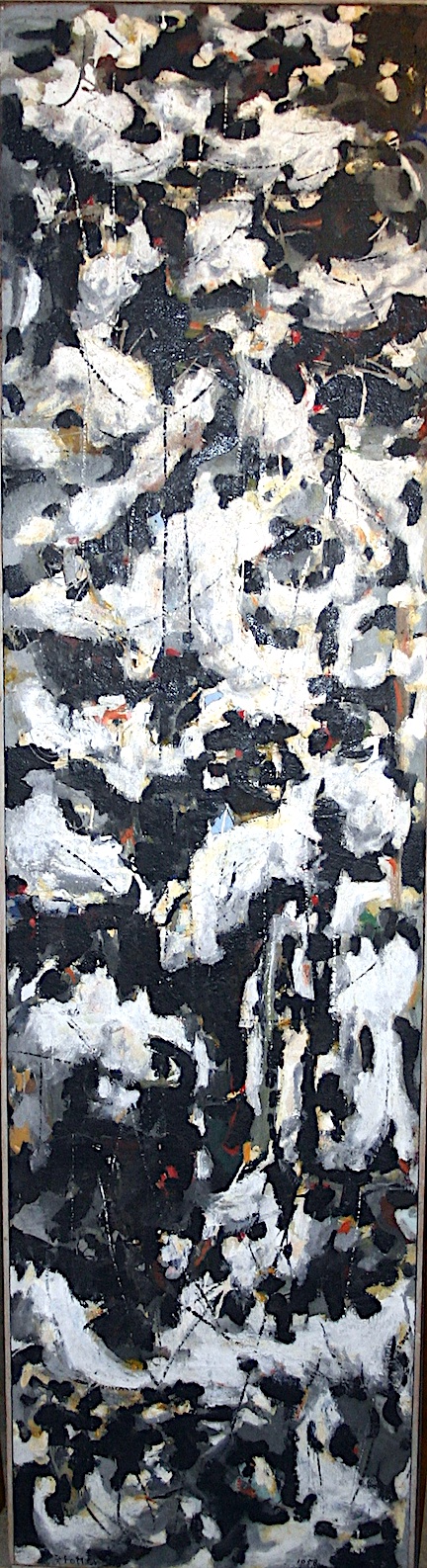

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

6 x 45 inches (15.24 x 114.3 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

9 x 54 inches (22.86 x 137.16 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

5 x 65 inches (12.7 x 165.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

34 x 37 inches (86.36 x 93.98 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

54 x 37 inches (137.16 x 93.98 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

40.5 x 32 inches (102.87 x 81.28 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1958

76 x 20 inches (193.04 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

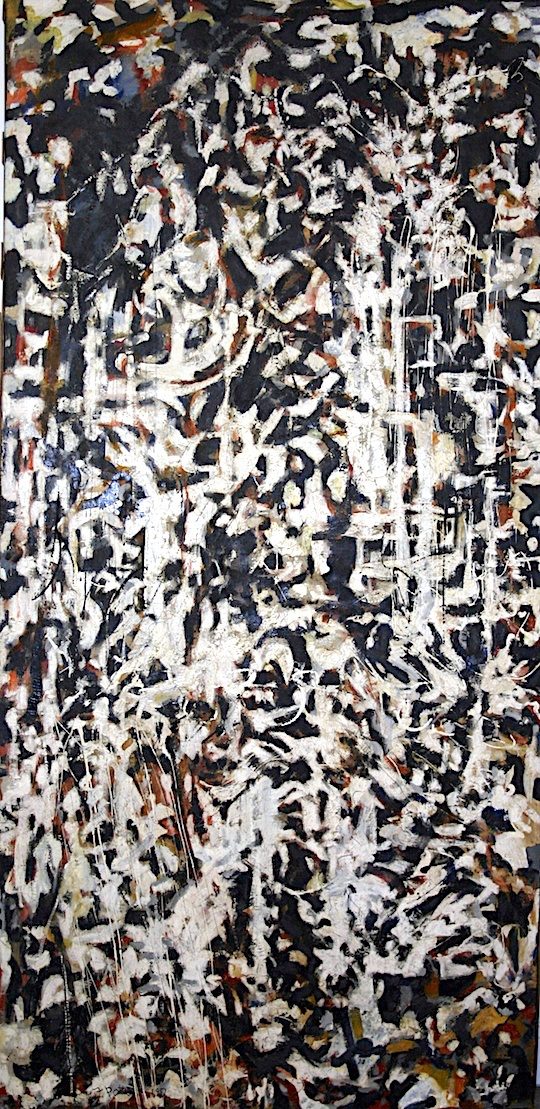

DETAILSUntitled, 1956

96 x 48 inches (243.84 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

43.5 x 88 inches (110.49 x 223.52 cm) -

DETAILS

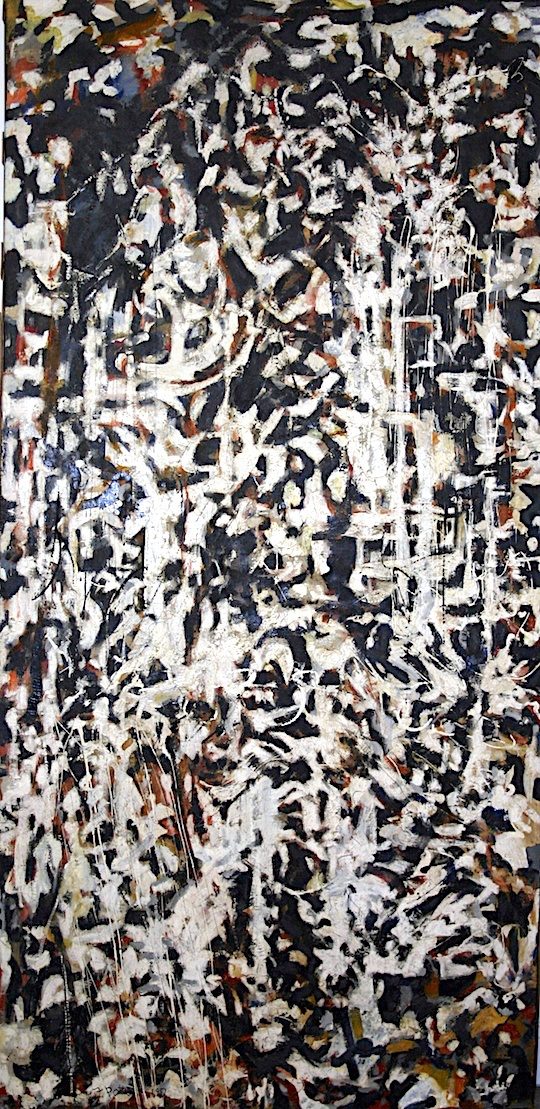

DETAILSUntitled, 1951

97 x 46.5 inches (246.38 x 118.11 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf Portrait, 1954

45 x 57.5 inches (114.3 x 146.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

8.5 x 5 inches (21.59 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

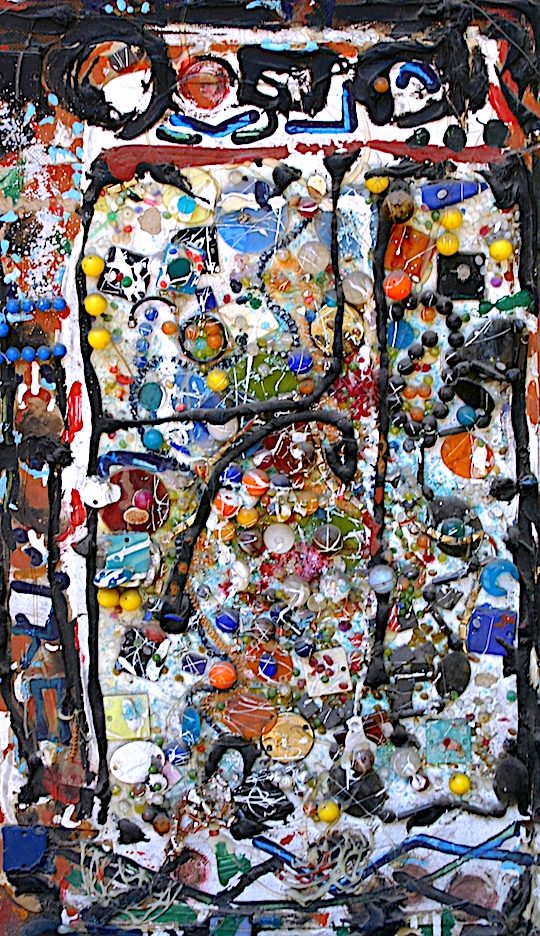

DETAILSUntitled, 1970

42 x 20 inches (106.68 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

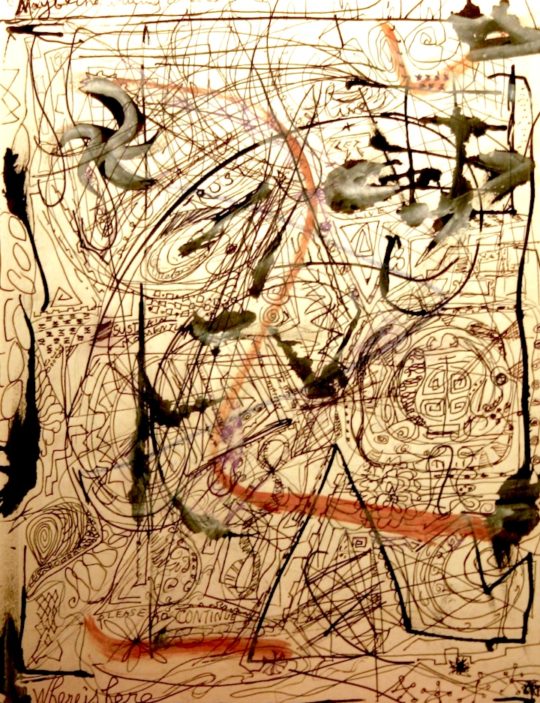

14 x 9 inches (35.56 x 22.86 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

11 x 8 inches (27.94 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

9.5 x 12 inches (24.13 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

9.5 x 8.5 inches (24.13 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1965

9.5 x 8.5 inches (24.13 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

10 x 11 inches (25.4 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

15.5 x 11 inches (39.37 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

8.5 x 5 inches (21.59 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

8.5 x 5 inches (21.59 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

6 x 45 inches (15.24 x 114.3 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

9 x 54 inches (22.86 x 137.16 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

5 x 65 inches (12.7 x 165.1 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

34 x 37 inches (86.36 x 93.98 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1954

54 x 37 inches (137.16 x 93.98 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

40.5 x 32 inches (102.87 x 81.28 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1958

76 x 20 inches (193.04 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1955

48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1956

96 x 48 inches (243.84 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1950

43.5 x 88 inches (110.49 x 223.52 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled, 1951

97 x 46.5 inches (246.38 x 118.11 cm)

No News found.

No Events Found.