Discovering an Inside-Out Artistic Polymath

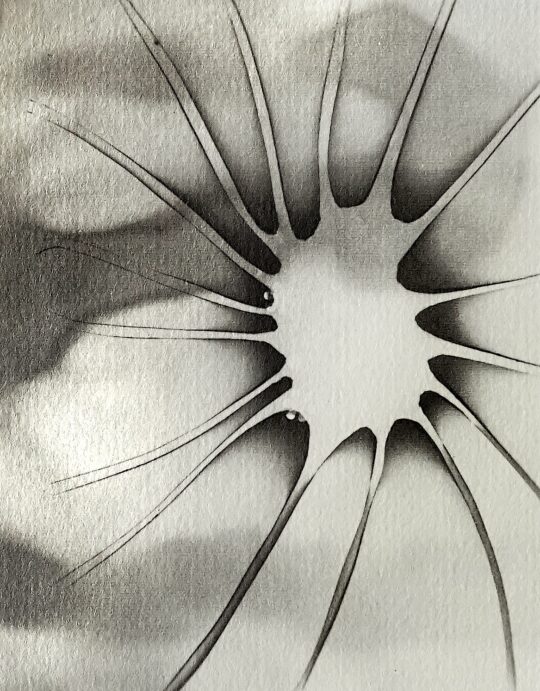

The recent rediscovery of a collection of 103 extraordinary photograms created by Fredric Karoly has produced some surprises for art historians.

Research reveals an artistic polymath whose incessant experimentation creating innovative photograms during the mid-1940s formed an important but hidden collection that stands unique in the history of photography. Also revealed is Karoly’s heretofore hidden influence upon his friend Pablo Picasso — completely missed by the master’s many biographers. Unfortunately, many details of Karoly’s life are missing, but notes left by his son help to put together the puzzle of one of America’s most innovative artists who was nearly relegated to oblivion.

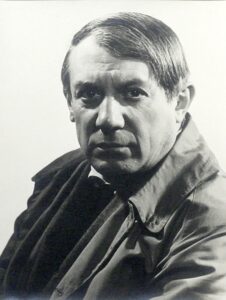

![]()

Karoly was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1893. He was painting by 12, during an explosive period where the avant garde was led by the Fauves in France and the Futurists in Italy and Russia. In 1914, at 21, he was inspired to make the pilgrimage to Paris to study at one of its art academies. But in early August, his dream was cut short when World War I suddenly broke out. Just days later, Karoly was arrested and placed in one of the first internment camps set up to detain civilian prisoners — particularly Austro-Hungarians and Germans. France had quickly complied with Britain’s “Aliens Restriction Act,” which deemed such foreigners “enemy aliens.” Fortunately, during the next four years of internment Karoly received regular art instruction from Ernst Kropp [1880–c.1930], a painter from Munich who, as a Francophile, made extended stays in Paris throughout his life.

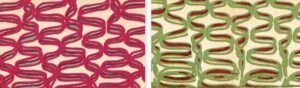

Karoly was released after the war ended in 1918 and resumed his art studies in Paris. However, by 1920, he was attracted to Berlin, a booming cultural center entering what became known as its “Golden Years.” Although he was there to study architectural engineering, he was also exposed to the Dada movement and Russian Constructivism. There he met many painters, photographers, and writers also drawn from Eastern and Central Europe. He also met a beautiful seventeen-year-old Austrian woman in 1925 and they had a son that year. Karoly put painting on a hiatus and became focused on becoming established in the fashion design industry. His strategy was to work a short stint in London and then move on to New York. He left his wife and child behind, apparently until he became established. In 1926 he arrived in New York City and quickly found success as a fabric designer. His creativity in fabric design, marked by intensive research and heuristic experiments in styles, continued to propel his success. For example, a design method he devised based on standard typewriter characters inspired his patterns for weaving or printing modern textile designs. He also used sculptural wire maquettes for the same inspirational purpose. In 1930 he became an American citizen, and his wife and son joined him in 1932. 1

By the end of the 1930s, a major shift was under way in the art world. The artists of Europe’s cultural avant-garde in Berlin, Vienna, and Paris were dispersing. Virtually all the major artists who played significant roles in establishing the Surrealist movement in Paris in the mid-1920s were now seeking refuge in New York. The first escaped just before the Nazi blitzkrieg of Europe in 1940. More shock came in 1942 when the Nazis began purging France of thousands of modern artworks, either burning them in bonfires or dumping them at auctions. This was the year when New York became the new home harboring many Surrealists, including the stars of the movement, such as André Breton (who wrote the first Surrealist manifesto in 1924), Marcel Duchamp (the father of Dada), Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, and many others. Peggy Guggenheim, also newly returned from Europe in 1942, quickly opened her gallery, Art of This Century, further fostering the Surrealist renewal.2

As a young artist in his native Hungary, and later in France and Germany, Karoly was keenly aware of the movements of Surrealism and Dada. But for most Americans, their first awareness of these movements came in 1931 when the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut, mounted “New Super-Realism.” It was the very first Surrealist exhibition in the U.S. Just a few months later, virtually the same exhibition opened at the Julian Levy Gallery in New York. Levy had befriended avant-garde artists such as Duchamp, Man Ray, and others during a three-year period in Paris, and when he returned to New York late in 1931 he established his eponymous gallery. Early in 1932 he staged the landmark multi-media exhibition, “Surrealism: Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs.” He was the first in New York to display the works of the Paris Surrealists. Just a month later, he mounted “Modern European Photographers,” which included László Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray (who arrived in the U.S. in 1937 and 1940 respectively). Later, in 1936, the Curator of the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred Barr, followed up with “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism.” In 1938, André Breton and Paul Éluard organized the movement’s first group show in Paris, showing works by sixty artists at the “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme” — which became a wildly popular and provocative spectacle at the Wildenstein gallery. Further promoting the fantasies of Surrealism was Dalí’s theatrical and erotic Dream of Venus pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Reimagining the Photogram

By 1942, Karoly had divorced but his success allowed him to take an apartment in the Barclay, a high-society residential hotel at 111 East 48th Street (right) that boasted a roster of celebrity residents that included Bette Davis, Marlon Brando, Ernest Hemingway. (When the Barclay became the InterContinental Barclay Hotel in 1978, Karoly remained there for the rest his life as the last hold-out with a lease.) 1942 was also when the Surrealist energy in Paris had been fully exported to New York — and Karoly set out to become immersed in the threshold of a newly established and vibrant milieu of artists, poets, and writers. As an artist who had continued to paint in parallel with innovative commercial design, he likely felt he was already part of the avant-garde. His decades of success in the design world allowed him to abruptly quit his job and refocus his creative energy. His prominence was such that when he quit the high-end ready-to-wear label Davidow in 1942, Women’s Wear Daily broke the news.3

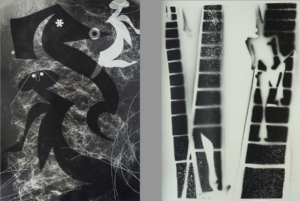

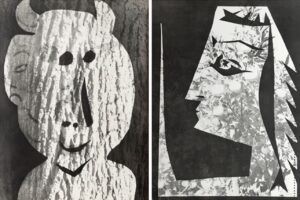

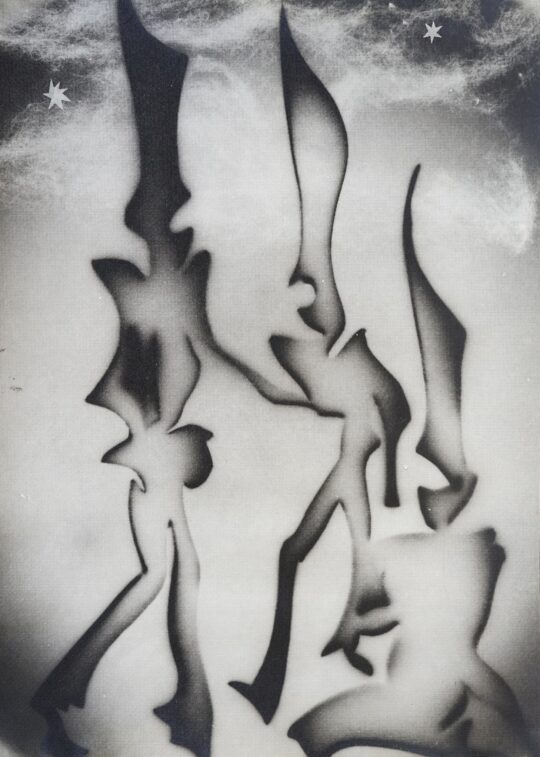

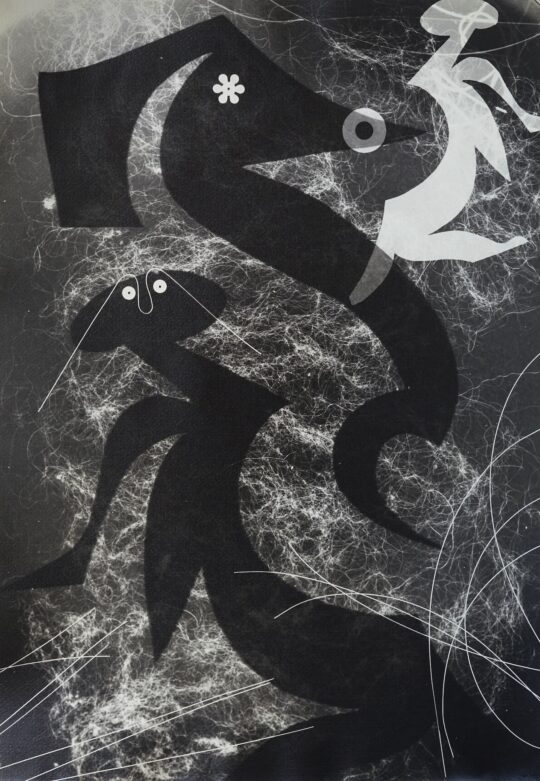

Karoly was inspired to make his mark within the vortex of the Surrealist movement by reimagining the photogram. He was aware of the brief history of the first abstract photograms, created by Christian Schad in 1919.4 These were followed in 1922 by the photograms of Karoly’s fellow Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy — who had been teaching this medium from 1937-onward as the head of “The New Bauhaus” in Chicago. Coincidentally, May Ray also created his first photograms in 1922.5 Karoly’s photograms — likely begun by 1943 and extending into 1947 — were quintessentially avant-garde in their imagery, at once abstract and surreal. They stood apart from the photograms of his peers owing to their complex technique, previously unheard of in the history of photography. Photogram expert Terence Falk, whose full report on the artist’s innovative technique is also published here on DiAA, stated:

“Karoly successfully hybridized the processes of the traditional photogram, together with traditional black and white darkroom printing

techniques, to achieve his vision. These prints utilize the act of creating states of variations as he progressed with his ideas and

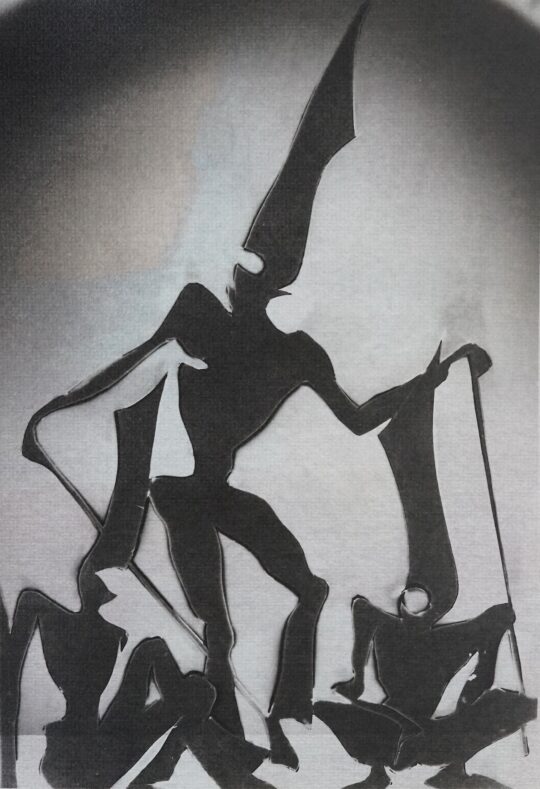

experimentation. The photograms he proposed to e.e.cummings for the Anthropos series are steeped in surrealism. They invoke a

theatrical narrative with the feel of Indonesian shadow puppetry. Other purely abstract compositions utilize carefully cut paper shapes, string,

wire mesh, and various objects. Still others appear to be of mysteriously organic origin drawn from a surreal world.” 6

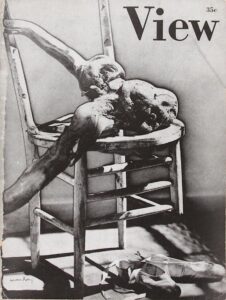

One catalyst for Karoly’s creative venture — besides his nature for being a persistent experimenter in various mediums — was his friendship with Charles Henri Ford [1908–2002] and Parker Tyler [1904–1974]. Ford and Tyler had established their presence within the avant-garde in 1933 with their collaborative novel, The Young and Evil, in Paris. Centered on their gay experiences in Greenwich Village, their book was so scandalous that export to the U.S. was denied and the shipment to England was burned. When they launched a new magazine in 1940 called View it quickly represented New York’s vanguard in the arts.7

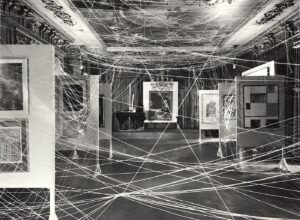

The magazine’s primary model was Minotaure, edited by André Breton. When it ran in Paris from 1933 to 1939, Minotaure illustrated Surrealist works and featured poetry, critical essays, and philosophy. But during the war years, it was View that took over as the period’s most influential proponent for the Surrealist movement. It was not lost upon Karoly that Ford and Parker’s list of acquaintances read like a Who’s Who of the avant-garde. All the leading figures of the movement contributed to View — including André Breton, Marcel Duchamp (the advisory editor), e.e. cummings, Man Ray, and Pablo Picasso. When View was first published in New York in 1940 it quickly put the city at the center of the avant-garde. View also became influential in shaping the ideas of the artists of the budding New York School, so there is little wonder that a significant endorsement came in 1942 from the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors in 1942 — led by Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Milton Avery, and Meyer Schapiro. Also, late in 1942, fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli promoted the Surrealists’ naturalization toward citizenship by spearheading a benefit exhibition “First Papers of Surrealism,” curated by André Breton and Marcel Duchamp, and held at the Whitelaw Reid Mansion at 451 Madison Avenue.

e.e. cummings

It was likely by 1943 when Ford and Tyler introduced Karoly to e.e. cummings [1916–1962], America’s edgy and provocative bohemian poet. Cummings was working on reviving in book form one of his short theatrical plays from 1930 that was never performed — Anthropos: The Future of Art. Anthropos simply means human in Greek, but it also refers to the first human being. Knowing that Cummings was drawn to Dada and Surrealism during his early visits to Paris, Karoly proposed that his photograms, showing theatrically charged abstract figures, be used as illustrations. The book was published in 1944 by Cummings’ close friend and Greenwich Village neighbor Samuel A. Jacobs in an edition limited to only 222 copies. However, Cummings elected to have Jacobs’ modernist typography stand alone, with no illustrations. Ever since Jacobs published Cummings’ first book of poems in 1923 (Tulips and Chimneys), Cummings relied on his guidance in book design. In short, “Jacobs’s use of sans serif type, an asymmetric page, and white space complemented Cummings’ visual poetic radicalism. The Jacobs-Cummings collaboration significantly defined typographic as well as literary modernism.” 8

Hugo Gallery

Undaunted, Karoly continued to pursue his new approach to the photogram. In 1945 he was introduced to the director of Hugo Gallery at its inaugural exhibition — organized by Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, and entitled “The Fantastic in Modern Art.” The director, Alexander Iolas, had retired from a successful career as a ballet dancer to pursue his passion for art, and was drawn to the Surrealist movement. The gallery soon became prominent in New York and held a major solo exhibition for Joseph Cornell in 1946. In 1947, Iolas mounted a major exhibition of paintings by René Magritte as well as the Surrealists’ last group exhibition before their dissipation, called “Bloodflames 1947,” designed by Frederick Kiesler. Also in 1947, Iolas included Karoly’s work in a four-person exhibition and followed up in 1948 with Karoly’s first solo exhibition, which included oils on canvas, wire montages, pen drawings — and photograms.9

One of the View’s art critics was Belgian poet and intellectual Leon Kochnitzky [1892–1965] who, in a special 1945 issue dedicated to Duchamp, wrote the essay, “The Limit of the Probable in Modern Painting.” 10 Kochnitzky reviewed Karoly’s photograms in the 1948 solo exhibition at Hugo Gallery, declaring:

“We do not know what kind of media Karoly will adopt in his next works, but we may predict that while his mysterious ecstatic gifts reside within him, he will continue to translate and express through these different processes, his strange and dramatic visions, so representative in the strange and dramatic world in which we dwell.”

Parker Tyler also wrote about the Hugo exhibition:

“In the absolute painting which Fredric Karoly has lately undertaken, the modern artist ceases to observe even the old laws of the picture, the primordial law of the image, the basic symbol. We are therefore surprised at the extreme expression of liberty-making in paint which Karoly, outstandingly and resolutely, has taken to fresh ground. These canvases are the ‘photographs’ of an absolutely invented reality — Their reality is framed in the conventional four sides in the way the world is framed by an ordinary photograph, except that the elements of absolute painting have no pre-existence.”

The Dénouement of Surrealism in New York

“When the war stopped and everybody could go back, I said,

‘We’ve had it here. This is my war work. I’m going back to Europe.’ ”

— Charles Henri Ford, from Bruce Wolmer’s interview in Sept 1986 (Bomb, 1 Jan 1987)

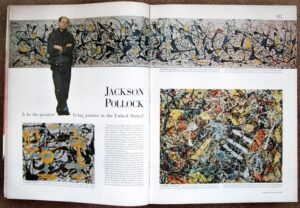

Historically, the war years were an extraordinarily vital period for the Surrealist avant-garde in New York. But the bubble popped on May 7, 1945, when the German Third Reich unconditionally surrendered — and Japan followed in September. Breton and most of the other artists in exile returned to France or moved elsewhere. What had been a provocative movement was fading. In 1947, the eight-year reign of —View — the last of the Surrealist magazines, ended. The several other art publications that had jumped on the bandwagon between 1946–1948 suddenly realized they had miscalculated their timing and soon closed. By 1949, and through the 1950s, the art of the Surrealists increasingly seemed old-fashioned in the face of Abstract Expressionism. Two powerhouses closed: Peggy Guggenheim closed her gallery in 1947 and soon resettled in Venice; Julien Levy closed his gallery in 1949. Then on August 8th, an article appearing in LIFE magazine generated unintended consequences. The headline of a two-page spread showing the irascible Jackson Pollock posing in front of one of his big paintings asked: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

While that headline could be interpreted as mocking Pollock’s drip-action paintings, it was also a harbinger declaring that the so-called New York School and its Abstract Expressionist painters had also won a war. They had captured international outrage in wresting the title “Capitol of the Art World” away from the School of Paris. As New York’s position became solidified, its cultural elite had a new intrigue: art as investment — aptly illustrated by Norman Rockwell’s satirical 1961 cover for The Saturday Evening Post showing a Wall Street type contemplating a Pollock.

The Magical Power of The Painting-Object

Karoly made his own course change in 1948. First, he carefully boxed his photograms and put them in storage. Next, he agreed to become the Fashion Director for the Simplicity Patterns Company with the charge of developing a new department for “Designers’ Patterns.” At the same time, he joined in partnership with a wealthy patroness, Mimi Bailiff, to launch an even more ambitious venture — Perspectives, Inc. Their objective was to teach established abstract artists how a fresh approach to textile design could be utilized for women’s apparel and home furnishings. Located at 54 East 51st Street, this business included a recruiting arm — the “Industrial Design Workshop” — and a promotional arm — Perspectives Gallery. Their inaugural exhibition in 1948 featured the designs of eleven American abstract painters and sculptors.

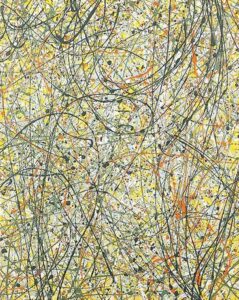

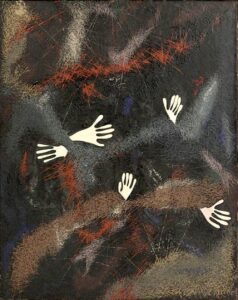

Meanwhile, Karoly continued his course change in painting. While he was among the first to experiment with Pollock’s all-over drip-action technique, he also responded with his own innovation. From 1948 to 1951, he created a series of paintings whose dominant technique did not involve dipping his brush into pigments (or flinging them). Instead, he cut thin pieces of either matboard or wood into different lengths, dipped their hard straight edges into his paint, and then stamped them onto the canvas. The resulting organic shapes appear to be composed of the needles of a pine tree. He created many paintings with this technique from about 1948 to 1951. First exhibited at the Hugo Gallery in New York in 1948, they were also shown at The Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris from 1949–1952 and at Galerie Mai in 1949 (which Aimé Maeght opened in Paris in 1946). In the catalogue essay for the Galerie Mai exhibition, Jean-Luc de Rudder wrote: “Karoly’s painting is situated at the supreme point of the concerns of formal poetics of this time.” Those poetics, he noted, were “the magical power of painting-object.” He further observed, “I imagine Karoly, working in a kind of hypnosis — object-subject — arousing in the things that surround him an irrational and unusual use.”

The Photogram…and Visiting Picasso

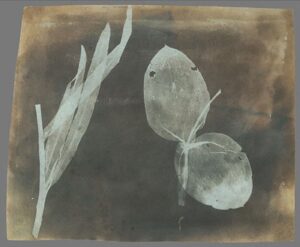

The first experiments in placing objects on photosensitive paper to create their silhouettes were conducted in the 1830s by Henry Fox Talbot in England. But it was not until the first quarter of the 20th century when the medium that came to be called photograms was revived by avant-garde artists. Picasso first became intrigued in 1922 when Man Ray showed him his photograms (which he named “Rayographs”). That year, Man Ray published a now very rare portfolio of 12 prints of Rayographs — Les Champs Délicieux — in an edition of 40. However, because photograms are by nature unique, producing a limited edition meant that he used his large format view camera to make copy negatives of each of the 12 unique photograms (7 x 9.5 inch/18 x 24 cm negatives). As Terence Falk points out in his “Technical Assessment of Fredric Karoly’s Photograms,” Man Ray needed to simply make copy prints of the Rayographs to produce his limited edition. But for Karoly, that was just a first basic step to which he would add many more.

None of Picasso’s many biographers were aware that Karoly met with Picasso in Vallauris Golfe-Juan during August 1948. It is unknown whether their meeting came about owing to introductions from Ford and Tyler, the editors of View, or to other mutual connections with Parisian Surrealists who had earlier made New York their temporary home. Picasso’s long association with the French Surrealists of the 1920s was well known, as were his contributions to the Surrealist publication Minotaure — and later to View. Immediately following the end of the war, Picasso settled on the Côte d’Azur for good. He had come to know the region well, having visited since 1920. After the war, he moved four times to different villages, each no more than two-and-a-half miles apart. At their center was Vallauris Golfe-Juan where he lived in the Villa La Galloise from 1948 to 1955. Well aware of the 400-year reputation Vallauris had established for pottery, Picasso burst into creative playfulness at the Madoura workshop while passionately pushing the possibilities of ceramics and another medium new to him: linocuts.

Man Ray briefly described in his autobiography the accidental manner by which he discovered the photogram process in 1922, and how he subsequently shared these works with Picasso. Most of Man Ray’s stories are instead largely focused on his many gatherings on the Côte d’Azur with Picasso and other artists and poets. The last time Man Ray was with Picasso was in 1937 before the Nazis invaded France. In 1940, Man Ray returned to America and would not see Picasso again until 1955. Yet Picasso made his first photograms in 1953 in collaboration with André Villers [1930–2016], fifty years younger. This shines a special light on Karoly’s visit with Picasso five years earlier, in 1948. Karoly had just enjoyed his solo exhibition at Hugo Gallery, which included his photograms. It is therefore a reasonable assumption that one of their many topics of discussion was Karoly’s innovations with the photogram… thereby rekindling Picasso’s interest in the medium.

Picasso had also just completed a series of ceramic plates when he met with Karoly that summer — and Karoly brought two of those plates home with him. He also brought home a pen & ink drawing — Tête de Faune — dedicated “À Fredric Karoly” and signed and dated “Picasso, Golfe Juan, 10 Août 48.” A snapshot taken that August shows the two artists engaged in conversation at the Golfe Juan shore. Picasso was visited by many friends during this fertile period of creativity but none of his biographers mention Karoly.11

It had long been thought that Picasso’s creative connection to photography had restarted with Gijon Mili [1904–1984]. A photographer for LIFE magazine, it was Mili who in 1949 famously used long exposures to capture Picasso as he waved a flashlight in the air, “drawing figures with light.” However, Picasso must have known that the first “light painting” was created in 1935 by his friend Man Ray, called Space Writing (Self-Portrait). After Mili, the final photographer with whom Picasso would collaborate was the aforementioned André Villers. Beginning in 1953, Picasso made cut-outs of faces and animals, and together with Villers arranged them on photosensitive paper, which Villers then exposed to light. The results were the simplest of photograms showing white silhouette shapes against a black background, while some of the shapes overlap or merge with Villers’ straight landscape photographs. In 1962, thirty of these photograms were reproduced as a book, The Diurnes, with text by French poet Jacques Prévert.

New Approaches to Painting for an Irascible Character

Karoly’s early award-winning fabric designs were exhibited at MoMA from the mid 1940s through the 1950s. Yet, the mid 1940s was also when he created his Surrealist photograms. Here was a perpetual experimenter who clearly welcomed the challenges of devising innovative responses to newly emerging styles and techniques. Certainly, he could not resist diving into Abstract Expressionism. His untitled oil on canvas from 1949 (shown above) shows that he quickly grasped how to create the rhythmic drips and splatters of Pollock’s drip-action technique, weaving layers of webs to create a sense of depth. Karoly’s canvas is dated 7/24/1949 — painted just two weeks before Pollock’s decisive breakthrough publicity in LIFE magazine. However, it may be surprising to note that during this period Karoly was also painting geometric abstractions. One example is his Space Computation from 1949 (unlocated) which he exhibited at the Yomiuri Indépendent Exhibition held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in 1951. While lasting only from 1949–1963, this annual exhibition firmly positioned postwar Tokyo as a center for radical and avant-garde contemporary art.

By the mid-1950s, Karoly had also tackled Color Field painting. His broadly washed fields of diluted oil pigments saturated his canvases. These would soon find variations, some with drips and splatters and others joined by multi-layered grids.

In 1957, Karoly closed Perspectives and its Textile Design Workshop and focused on painting. In 1959, the Miami Museum of Modern Art (later renamed the Lowe Art Museum) mounted a 10-year survey of his work (1949–1959). A reviewer noted that the exhibition “includes some pictures which this artist believes were created by ‘automatism’ — that is, by his subconscious mind.”12 The next year, the museum showed his Color Field canvases saturated with oil-based pigments. As he approached his seventies, Karoly must have been anticipating the kind of late-career recognition that would firmly position him in the pantheon of American artists. According to Karoly’s son, Robert E. Karoly, some major gallery owners did step forward to express their interest, only to discover an irascible character. Leo Castelli considered him very talented but realized he would be one with whom it would prove too difficult to work. Tibor de Nagy was planning an exhibition when Karoly wound up abruptly canceling it because of a disagreement about how his paintings should be presented. Undeterred, Karoly entered the 1960s continuing to experiment with different mediums. His paintings began including elements inspired by Japanese and Zen calligraphy, and his surfaces were sometimes marbleized from mixing oil and water. He also created multi-media assemblages on linen, often utilizing a variety of objects such as Plexiglas or paper cups. Eventually these painting-sculptures transitioned fully to three dimensions.

Two New York galleries — Judson Gallery and Green Gallery — were the pioneers promoting Pop Art in 1960. Two years later, Sidney Janis made the greatest impact for Pop Art with his groundbreaking International Exhibition of the New Realists. By 1964, Karoly had taken up the challenge of Pop Art and was working in a studio at 3 Crosby Street in SoHo. That year, he created a screen-printed oil on canvas portrait titled Picasso, 1949. Although it was created in 1964 it is based on a photograph taken in 1949. Since it does not appear in any Google image search, it was likely shot by Karoly. This would also mean that Karoly would have visited Picasso again, in 1949. According to Karoly’s son, his father created similar screenprint portraits on canvas of de Kooning and other significant artists of his generation. Like Rauschenberg and Lichtenstein, Karoly emphasized the effects of exaggerated Ben-Day half-tone dots.

In 1965, Karoly created a screen-printed canvas, The First Spacewalk, Ed White (oil and acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 inches). This image was a composite of two photographs. One shows White holding his tether as he floats above the second image, which is ambiguously either Earth or the destination of the future — the moon. This image summons Warhol’s Moonwalk, which is also a composite of two photographs. One shows Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon’s surface above the second image, which is a deep view of the moon’s surface. However, Warhol’s Moonwalk — the last screenprint published just before death in 1987 — was created 22 years after Karoly’s Spacewalk. These works were represented by Richard Castellane, one of several new art dealers riding the Pop Art wave. His Castellane Gallery on Madison Avenue was the first to show Yayoi Kusama.

Karoly’s Spacewalk of 1965 is just one example of how a succession of new and disparate movements was peaking — with seismic consequences. Prominent galleries were also promoting Minimalism, Op Art, and Hard Edge (the last having emanated from Los Angeles in 1959). Each was an overlapping assault reacting against, or morphing from, the Abstract Expressionist movement. Clement Greenberg, the period’s most influential critic, named the new era one of “Post-Painterly Abstraction.”

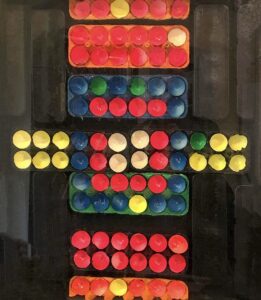

Always changing creative gears, during the 1960s Karoly created a series of sculptures composed of objects arranged in geometric patterns or grids to be viewed under ultra-violet lights. The earliest signed and dated piece — Piccolo — is from 1964 (right) and was possibly inspired by Dan Flavin’s first fluorescent light installation just a year earlier. It is composed of small Dixie cups painted in DayGlow and flanked by mirrors within a beveled channel. In another example, Karoly painted seven dozen eggshells in DayGlow (left). Some of his constructions were on joined panels of stretched linen cut with slits, and the whole was back-lit with colored light and fiber-optic elements. These were exhibited at Hofstra University’s Emily Lowe Gallery in 1967.

Karoly’s delightfully torrid pace gave way in 1968. Without giving any reason, this artistic polymath made the uncharacteristic decision of refusing to exhibit or sell any of his works. He continued to paint at his apartment at the InterContinental Hotel but became increasingly reclusive. His daughter-in-law observed, “Fredric withdrew into his own little world in the hotel.” His was the last apartment that was protected by rent control.

A Radical Left Behind

When Karoly turned 85, he disposed of his valuable objets d’art and paintings by Old Masters at two Christie’s auctions in London.13 By this time he had also placed his life’s work in a storage facility in Spanish Harlem. His reclusiveness may have been owing to his frustration, increasingly weighted, over the failure to have secured lasting appreciation for his work. His was the same resentment that Man Ray expressed about New York collectors after his 1945 exhibition — “Objects of My Affection” at the Julien Levy Gallery — was a flop. Man Ray’s irritation may well serve as an appropriate epitaph for Karoly:

“New York had forgotten that I was one of the pioneer Surrealist painters…

The artworld was not yet ready for them. It is really unfortunate to be a pioneer;

it pays off to be the last, not the first.” 14

After Karoly passed away in 1987 at age 94 it was soon discovered that he had left no will, resulting in years of legal expenses and wrangling. Without a resolution, and after years had passed, the facility where all his art was stored had the right to liquidate the contents. Like an episode from the reality TV show, “Storage Wars,” his works were widely dispersed. Fortunately, Karoly had earlier sold his extraordinary collection of more than one-hundred photograms to a private collector who preserved them. Now, seventy-six years after they were created, this important body of work by a master — a radical left behind — has been rediscovered.

— Peter Hastings Falk

Footnotes:

1 While biographical details about Karoly’s life are scant, notes typed by his son, Robert E. Karoly [1925–2017] provided many facts. Interviews with Robert’s wife, Kathy, in June and July 2024 provided additional helpful details. In addition, the MoMA Library keeps an artist’s file that includes photographs of many paintings as well as exhibition announcements. The Frick Library also keeps an artist’s file.

2 Beginning in 1937, the Nazis destroyed tens of thousands of paintings labeled as “degenerate.” But it was not until 1940, when the blitzkrieg overwhelmed Western Europe, that the most desperate flight began. Below are some of the European Surrealists, many of whom were Jewish, who found refuge in New York City between 1938–1942. Most returned to Europe after the war ended: André Breton [1896–1966] lived in NYC 1941–1946; Marc Chagall [1887–1985] lived in NYC 1941–1948; Salvador Dalí [1904–1989] lived in NYC 1940–1948; Marcel Duchamp [1887–1968] lived in NYC 1942 became a citizen in 1955 but had a home in Paris where he died; Max Ernst [1891–1976] lived in NYC 1941, married Peggy Guggenheim, then Dorothea Tanning in 1946 and moved to Sedona, Arizona, became citizen in 1948, lived in Paris from the 1950s–1976; Leon Kochnitzky [1892–1965] lived in NYC 1940–ca.1945; Fernand Leger [1891–1955] lived in NYC and Connecticut 1938–1945; Jacques Lipchitz [1891–1973] lived in NYC 1941–1963; André Masson [1896–1987] lived in NYC 1940 and then Connecticut until 1946; Roberto Matta [1911–2002] first joined the Surrealists in 1937, lived in NYC 1940–1948; Piet Mondrian [1872–1944] lived in NYC 1940–1944; Man Ray [1890–1976] lived in Los Angeles 1940, later NYC until 1951; Kurt Seligmann [1900–1962] Lived in NYC 1939–1962; Philippe Soupault [1897–1990] lived in NYC 1940–1945; Yves Tanguy [1900–1955] lived in NYC 1938–became citizen in 1948; Pavel Tchelitchew [1898–1957] lived in NYC 1934–1949 (he moved NYC from Paris with his partner, writer Charles Henri Ford); Ossip Zadkine [1888–1967] lived in NYC 1942–1945.

3 “Fredric Karoly Leaves Davidow Sportswear” Women’s Wear Daily, 3 Feb 1942, vol. 64, no. 23, p.18

4 Housefield, James. “Marcel Duchamp’s Guernica? His Twine, the “First Papers of Surrealism” (1942) and Aerial Warfare in Europe.” (The Space Between Literature and Culture: 1914–1945, an annual journal of the University of California, Davis). Proceeds from the exhibition went to the Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies (CCFRS), and organization that assisted French refugees who wished to become naturalized as U.S. citizens.

5 Christian Schad [1894–1982] was one of the few artists associated with Dada who remained in Germany and joined the Nazi party. In 1922, shortly after Man Ray [1890–1976] created his first photograms (he called “Rayographs”), he published a portfolio of 12 copy prints — Les Champs Délicieux — in an edition of 40 (Paris: Société Générale d’Imprimerie et d’Édition). The highest price of the five portfolios that have sold at auction is the $293,177 fetched in 2007. Seven individual copy prints from this portfolio have sold at auction, with the most recent being $25,000 paid in 2023 and $47,500 paid in 2016. The record price for a unique photogram by Man Ray is $1,203,750 paid in 2013 for a work dated 1922. The next two highest prices were for photograms dated 1924, selling for $485,000 in 2014 and $250,000 in 2016. László Moholy-Nagy [1895 Hungary–1946] created his first photograms in 1922. He came to Chicago in 1937 to run “The New Bauhaus: American School of Design,” which reopened in 1939 as “The School of Design in Chicago,” and was renamed in 1944 “The Institute of Design.” Three years after his passing, the school became a department of the Illinois Institute of Technology. One of his original photograms sold for a record $773,000 in 2014; followed by $568,248 in 2018; and, $447,000 in 2018.

6 Terence Falk’s “Technical Assessment of Karoly’s Photograms” follows this essay.

7 Charles Henri Ford was a poet, novelist, filmmaker, photographer, and collage artist. Ford’s circle of friends he met in Paris included Man Ray as well as his favorite poet, e. e. cummings, who made extended stays in there from 1917 to 1933. Parker Tyler was also a poet as well as film critic. In the art world, he is best known for his biography on modernist painter Florine Stettheimer.

8 “Reclaiming S.A. Jacobs: Polytype, Golden Eagle, and Typographic Modernism” (American Printing History Association, website 20 March 20, 2014). During the mid-1930s, Jacobs moved from Greenwich Village and established Golden Eagle Press in Mount Vernon. His special printing of special short-run limited editions was peaking around 1944 when he printed Anthropos. See also: Cummings, E.E. Anthropos: The Future of Art (Mount Vernon, New York: The Golden Eagle Press, 1944)

9 Alexander Iolas [1908–1987] opened Hugo Gallery in 1945 on East 55th Street at Madison Avenue, in honor of François Hugo, the last spouse of one of his financial backers, Donna Maria Ruspoli. The other backers were Elizabeth Arden and Robert Rothschild. Iolas’ early exhibitions showed works of European surrealist artists, and in 1952 he was the first to show works by Andy Warhol. He later opened satellite galleries in Geneva, Paris, Milan, Zurich, and Rome — making him a precursor of today’s mega-galleries

10 Leon Kochnitzky [1892–1965] was a Belgian poet, intellectual, and later art critic. Politically, he was a radical socialist who formed League of Fiume in 1919 with the purpose of establishing the coastal city of Fiume (now in Croatia) as an independent free state. That status was achieved in 1920 but lasted only until 1924 owing to persistent political revolts. Karoly’s native Hungary had recognized Fiume as an enclave serving as a valuable port. Kochnitzky was close to the Parisian Surrealists, and owned an important painting by Giorgio de Chirico, Testa di Manichino, which he sold in 1937 to his friend Philippe Soupault [1897–1990]. Like Kochnitzky, Soupault was also a poet, art critic, and political activist. Soupault and André Breton are considered the founders of the Surrealist movement. In 1940 Kochnitzky moved to the United States, dedicating himself to the activity of musicologist and journalist. It was Kochnitzky who alerted Max Ernst when he learned the Nazis had seized artworks from his Paris residence. As an art critic, Kochnitzky is best known for his groundbreaking book, Negro Art in Belgian Congo, which traces the influence of Congolese artists on European artists, including Picasso. As a contributor to View he met Karoly. He also wrote for Aimé Maeght’s magazine, Derrière le Mirroir in 1953 (No.52, Wilfredo Lam cover).

11 The snapshot of Karoly with Picasso is courtesy Dalton Delan, who as a boy met Karoly in Annecy, France, in 1967 while living with a French family. Delan, who became a documentary filmmaker, recalled he was impressed by the photograph because it proved Karoly’s connection to Picasso. “One evening, my mother’s friend Mimi [Bailiff] came to dinner with a date, painter Fredric Karoly. Hungarian by birth, he had palled around with Pablo Picasso after the war. As we got to know him subsequently, he gave my mother a photograph of the two artists together. I suppose he wanted to impress her, and I suppose he did. My mother had taken me many times to see Picasso’s intense Guernica at the Museum of Modern Art. Knowing his pal Karoly, I felt the heat. The vitality of proximity to greatness stuck with me and colored my career. Twenty feet from stardom, as the movie called it, my job was often to oversee others’ work. A footnote to fame.” Source: Delan, Dalton. “Sometimes We Steal from Others, as Time Steals from Us All” (The Berkshire Eagle, 13 May 2022). The ceramic plates by Picasso that Karoly brought back to New York appear in Ceramiques de Picasso, a rare folder from the exhibition of the same name held in 1948 at the Galerie d’Art in Stockholm, Sweden, published by Skira and illustrated with 18 color plates.

12 Reno, Doris. “Karoly Paints With His Subconscious” (Miami Herald, 13 March 1960)

13 In 1973, two auction catalogues for Christie’s London featured on their frontispieces as a consignor in: “Fine Pictures by Old Masters” on 13 April; and “Objects of Art and Clocks” on 31 May.

14 Ray, Man. Self Portrait. (London: Penguin, 2012, p.361)

Bibliographic Sources:

Bardi, Lina Bo. Exhibition review, Habitat magazine, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Buffalo AKG Art Museum — Picasso: The Artist and His Models — Man Ray (December 19, 2016

Daffner, Lee Ann and Pierce, Jane. “Man Ray’s Les Champs Délicieux Turns 100” (New York: MoMA magazine, 3 Feb 2022)

Falk, Peter Hastings. Who Was Who in American Art, 1564–1975 (Madison, Conn: Sound View Press, 1999)

Falk, Peter Hastings. The Annual & Biennial Exhibition Record of the Whitney Museum of American Art, (Madison, Conn: Sound View Press, 191)

Frick Art Reference Library — catalogue for Karoly solo exhibition at New Gallery (Eugene Thaw, Dir., Algonquin Hotel at 59 West 44th St, New York)

Neusüss et al. Experimental Vision: The Evolution of the Photogram since 1919 (Denver Art Museum, 1994)

Penrose, Roland. Portrait of Picasso (New York: MoMA

Picasso, Pablo, and Villers, André. Diurnes (Paris: Berggruen, 1962, edition of 1,000)

Ray, Man. Self Portrait. (London: Penguin, 2012)

Whitney Museum of American Art — The Frances Mulhall Achilles Library

Museum of Modern Art Library, Special Collections, New York City — Unpublished report by J.W. Phillips: “Fredric Karoly: A Preliminary Report on the Life and Work of an Unsung and Prescient Voyager in the Annals of American Abstraction”; also, an Artist file with miscellaneous uncatalogued materials.

Zervos, Christian. Dessins de Picasso, 1892–1948 (Paris: Les Editions Cahiers d’Art, 1949)

Exhibitions:

1947 Museum of Modern Art, New York — “Printed Textiles for the Home” [“The four prize-winning designs were selected from 2,433 entries from 44 states and the District of Columbia.”]

1947 Hugo Gallery, New York

1948 Hugo Gallery, New York (solo)

1949 Galerie Mai, 12 rue Bonaparte, Paris

1949-53 Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, Paris

1951 Biennale of Sao Paulo, Brazil

1951 Third Yomiuri Indépendant Exhibition, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum

1951 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York — Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting (No. 76: Diptych, June, 1951)

1952 Museum of Modern Art, New York — “Good Design”

1953 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York — Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting (No. 67: Ebb Tide)

1956 Museum of Modern Art, New York — “Textiles USA: A selection of Contemporary American Textiles”

1959 Martha Jackson Gallery, New York

1959–60 Miami Museum of Modern Art (a 10-year survey, 1949–1959. MMMA was the precursor to the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami)

1960 Stuttman Gallery, New York

1960 The Butler Institute of Art, Youngstown, Ohio

1960 The Art Institute of Chicago (Annual Exhibition)

1960 Miami Museum of Modern Art (“Color Field Paintings.”)

1960 Miami Museum of Modern Art (“Color Field Paintings.”)

1961 Brooklyn Museum, International Watercolor Exhibition

1961 Allan Stone Gallery “Fredric Karoly — Brushless Painting” (October 1961)

1963 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York — Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting (No. 66: Score of Silence)

1963 Westchester Art Society, White Plains, New York

1963 Cleveland Art Festival, Park Synagogue, Cleveland

1964 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York — Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture (No. 48: MultiMedia No.8)

1967 Emily Lowe Art Gallery, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York

Collections:

Kemper Art Museum, Washington University, St. Louis

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Museo de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Florida

Museum of Modern Art, New York

New York University Art Collection

Princeton University Art Museum (photogram)

São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil

Solomon Guggenheim Museum, New York

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Karoly Photograms

-

DETAILS

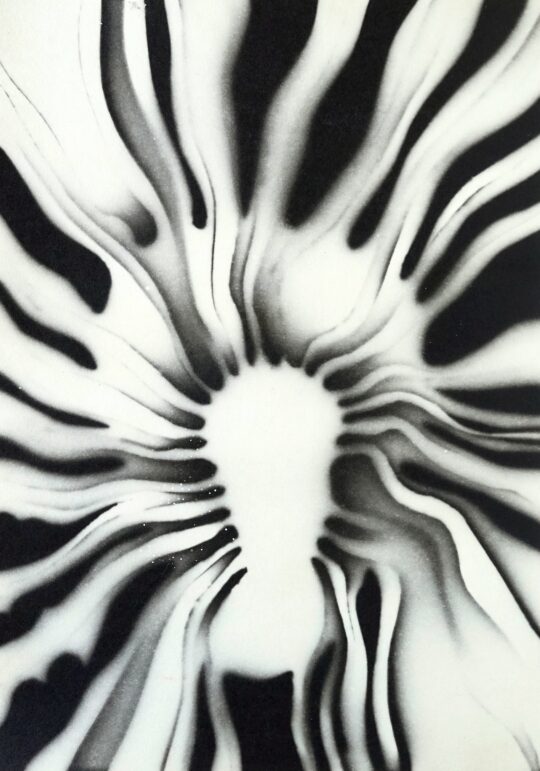

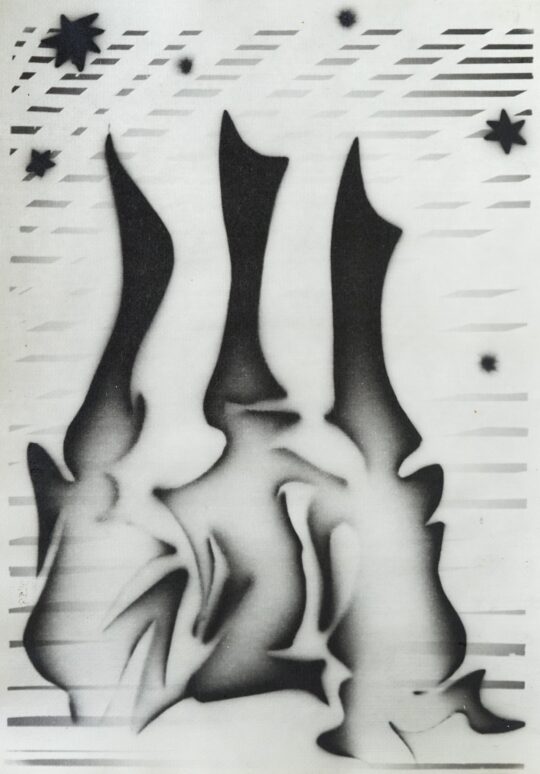

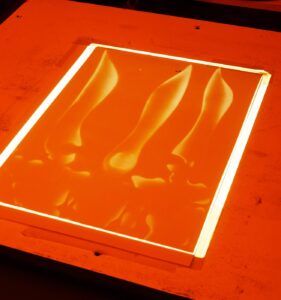

DETAILSUntitled No.98, Organics Series, 1944

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.92, Organics Series, 1944

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

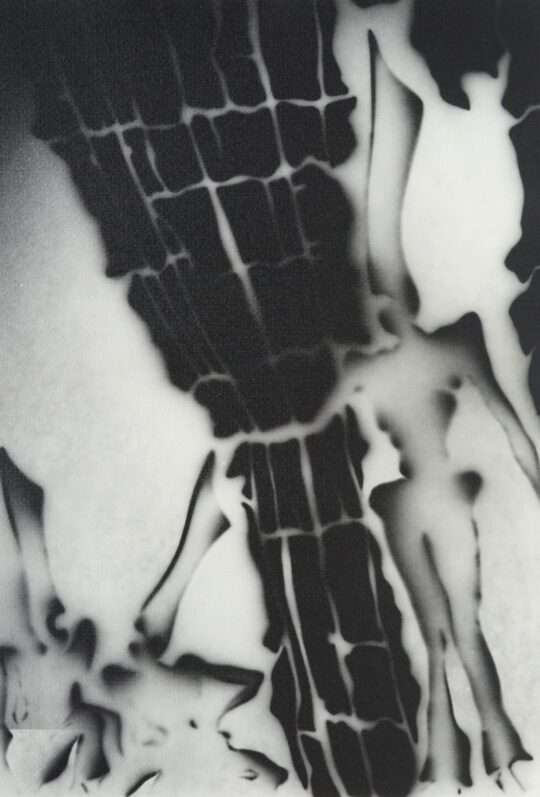

DETAILSUntitled No.95, Organics Series, 1944

12.5 x 8.5 inches (31.75 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

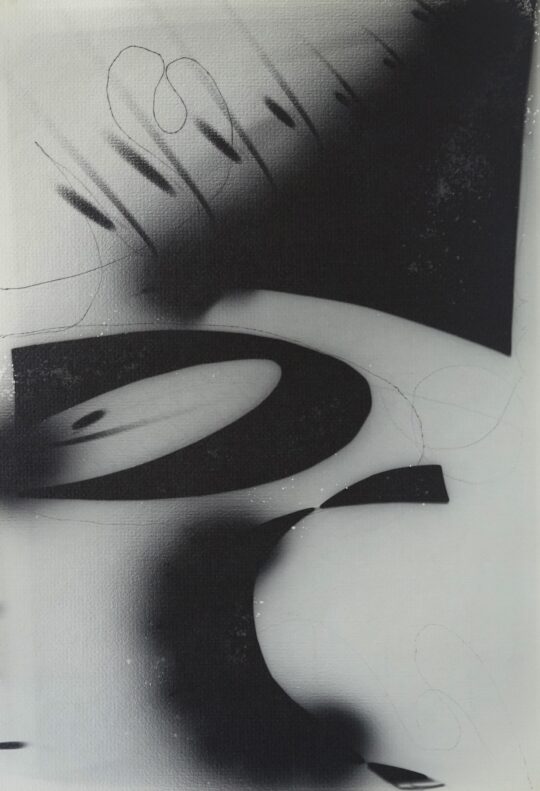

DETAILSUntitled No.74, Abstract Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.88, Organics Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.91, Organics Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

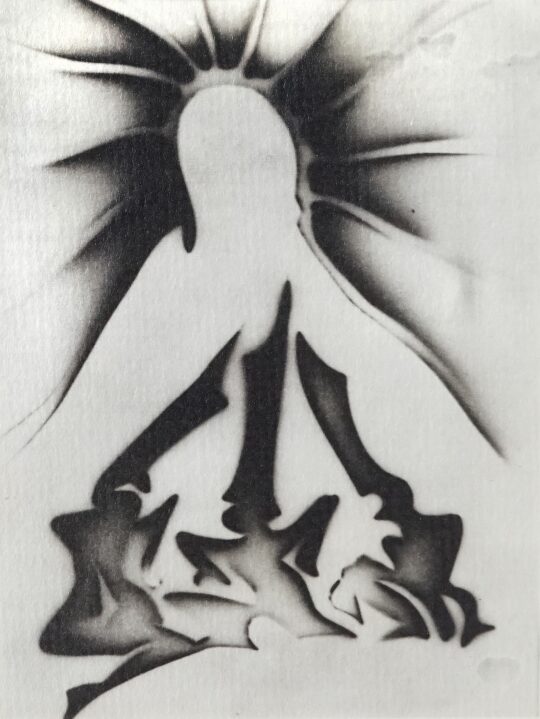

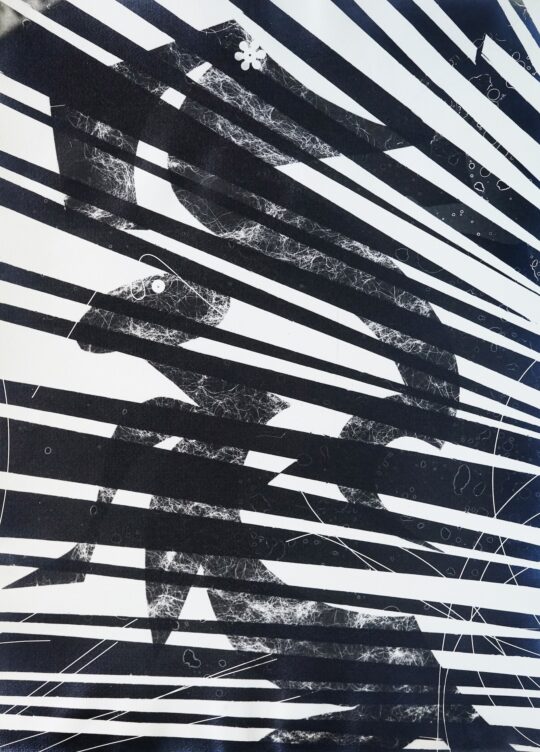

DETAILSUntitled No.19, Anthropos Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.29, Anthropos Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.25, Anthropos Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.77, Abstract Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.83, Organics Series, 1944

4 x 3 inches (10.16 x 7.62 cm) -

DETAILS

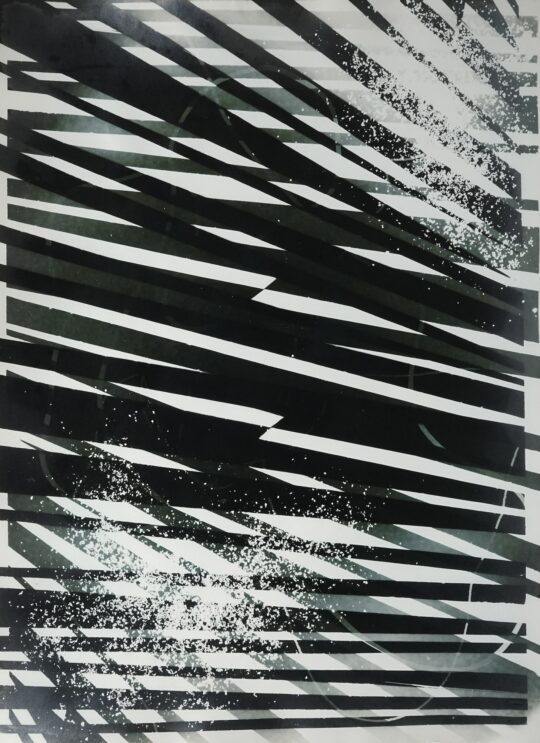

DETAILSUntitled No.81, Abstract Series, 1944

4 x 3 inches (10.16 x 7.62 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.37, Anthropos Series, 1944

12.5 x 8.5 inches (31.75 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.43, Anthropos Series, 1944

12.5 x 8.5 inches (31.75 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.46, Anthropos Series, 1944

12.5 x 8.5 inches (31.75 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.8, Anthropos Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.10, Anthropos Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.14, Anthropos Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.63, Anthropos Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

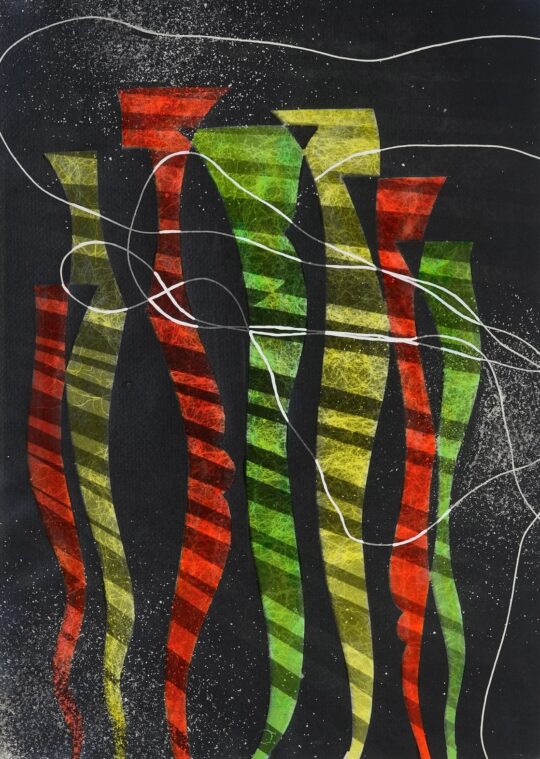

DETAILSUntitled No.100, Abstract Series, 1944

14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.76, Abstract Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.56, Anthropos Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.58, Anthropos Series, 1944

4.25 x 3.25 inches (10.8 x 8.26 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUntitled No.59, Anthropos Series, 1944

13.25 x 9.25 inches (33.66 x 23.5 cm)

Technical Assessment of Fredric Karoly’s Photograms

— by Terence Falk

Perspective on a Discovery

During extensive examination to uncover the secret of Fredric Karoly’s technical process in the creation of his photograms, I was struck not only by the unique quality of the images, but his visionary ability to see new possibilities in the art of photograms that up to this point (and since) had not been realized. In my practice of 50 years as fine art photographer, educator and photo historian, I have never seen photograms such as these. My ultimate discovery was that they represent a completely unique and never before seen approach to photographic image making.

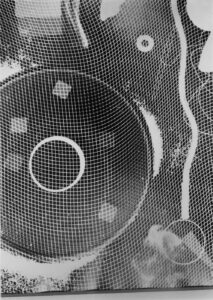

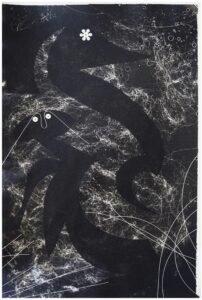

Karoly successfully hybridized the processes of the traditional photogram, together with traditional black and white darkroom printing techniques, to achieve his vision. These prints utilize the act of creating states of variations as he progressed with his ideas and experimentation. The photograms he proposed to e.e. cummings for the Anthropos Series are steeped in surrealism. They invoke a theatrical narrative with the feel of Indonesian shadow puppetry. Other purely abstract compositions utilize carefully cut paper shapes, string, wire mesh, and various objects. Still others appear to be of mysteriously organic origin drawn from a surreal world.

The following technical report describes the extensive experimentation behind Karoly’s production of photograms and negatives created between ca.1943 to 1948. His creative approach was so complicated that his process and its variations need to be explained with a greater degree of clarity than has heretofore been understood about photograms — even by those who have some familiarity with the darkroom. The reader will realize the variations are virtually endless.

Introduction

This report has been created to ascertain the following:

- How the photograms were created

- The role the negatives in the collection played in the creation of the photograms

- If any of the prints from the collection are copy images and not original photograms

A Brief History/Timeline for the Photogram

The Traditional Photogram Process Versus that of Karoly

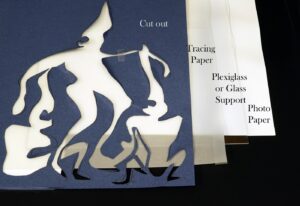

Photograms are created without a lens or camera. One simply places sensitive photographic paper down in the darkroom, adds objects on top of it, and then exposes the paper with an enlarger that is emitting only white light. (One could do the same with a bare light bulb or flashlight.) Upon development, any parts of the paper exposed to light will turn black, and those areas held back by the object remain white. This is paramount in understanding Karoly’s unique process, marked by two main factors that vary from traditional photograms: 1) his modification of light source at the enlarger; and, 2) his layering procedure.

Normally, a darkroom enlarger is used, and simply exposing the paper to its white light is sufficient (as seen below). However, Karoly’s procedure deviates from tradition in order to create incredibly complicated photograms.

The Karoly Process is quite different from the above

1) Cut out the main shapes on thin but opaque paper, possibly carbon or stencil paper —

keeping the cut-out pieces for a variation described later.

2) Above: Curl the edges of the cut shapes up and down to give them dimension.

This is very important since the farther away an object is to the paper,

an illusion of depth is created since the object is not absolutely flat on the photo paper.

Light can now bend around curved objects — and the result is a grey tone,

creating the illusion of depth and three dimensionality.

3) Place the unexposed photographic paper down first under the enlarger or other light source.

4) Add glass or plexiglass on top of the photographic paper. This serves to act as

a support for the cutout, which can be difficult to maneuver without such support.

Above Left: My recreation of a Karoly-like photogram from the Anthropos Series using flat cutouts.

Above Right: The same cutout but with its edges curved and then covered with tracing paper.

6) Add the cut figures on top of the tracing paper.

7) Expose the paper, most likely with an enlarger, but possibly other light source.

NOTE: The exposure time will greatly affect the level of gradation of the tonalities.

8) Process the paper normally. You now have a photogram of the cut-out figures.

Extremely Important!

It must be emphasized that at this point, there are two ways for Karoly to create the finished photograms.

The following outlines both options:

Option A:

9) Process and dry the resulting photogram. You now have a traditional photogram print consisting of dark tones on a white background.

10) Take this photogram print and photograph it with a view camera and traditional sheet film.

11) Process this film. You now have what I refer to as a “template negative.”

12) Take this negative (technically a copy negative of the original photogram), and place it in the enlarger

12) Take this negative (technically a copy negative of the original photogram), and place it in the enlarger

as you would if printing any traditional image-based negative, but now use its projected image to

expose the second generation photogram. This varies greatly from the traditional approach of

using nothing but white light, either from an enlarger or flashlight, to expose the paper.

Above: An image of one of Karoly’s negatives projected onto photographic paper in the darkroom.

13) By adding a safety darkroom filter under the enlarger lens (left), one can have unexposed paper under the enlarger,

turn it on, and see the projected image without affecting the paper. Now, the placement of additional items onto the paper

can be done precisely, since you can see the projected image on the paper. Once one is satisfied with the placement of

objects, the enlarger is turned off, the filter swung out of the way, and the paper exposed. Since the original “template”

photogram is now in film form, it can used repeatedly, adding, moving, replacing any objects on the photographic

paper under the enlarger. Endless variations are now possible.

14) With the template negative in the enlarger, Karoly could simply add items to the piece, such as thread, salt, sand,

14) With the template negative in the enlarger, Karoly could simply add items to the piece, such as thread, salt, sand,

cutouts, fabric, cotton, etc. He could easily see exactly where to place these items since the safety filter is being used

and the photo paper is not affected until he is satisfied with the arrangement. The use of the glass or plexiglass

support allowed Karoly to arrange the items and then carefully lift the whole assembly off the paper, expose and

process. If he didn’t like the result, he could replace the whole assemblage on the plexiglass over new paper,

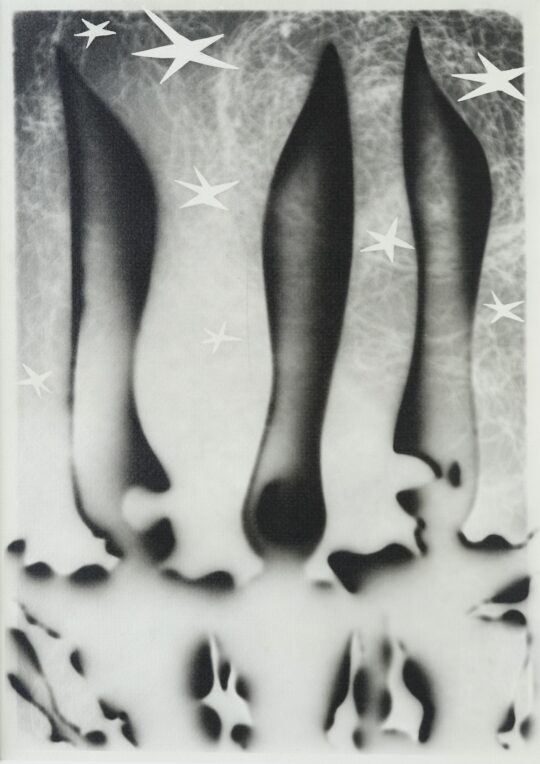

make subtle shifts in the objects and make a new exposure. (Above: My addition of cotton for clouds and cut out stars

were added in safelight.)

Test Results of Option A:

Keep in mind that after the template negative has been exposed, each part of the image is created with different exposure times.

They are not all done the same time. This reinforces the concept of the copy negatives in Karoly’s collection.

He may have simply wanted to make additional copies of something very difficult to replicate.

Additionally, note I am showing the edges of my re-creations that show variations in the border tones,

which is also seen in Karoly’s work. This proves the process of multiple exposures because the photographic

paper may shift, the cutouts may be placed in slightly different positions, etc.

Option B:

After cutting and bending the original figurative cut-outs as described earlier, Karoly could have simply placed

everything onto the glass or plexiglass, put that on top of photographic paper, and exposed all of it at once including the original

cutouts of the figures.

The problem with this option is that it does not address the simple question:

why does his collection include negatives of the figures alone? After all, if one is going to do

everything by layering all the elements on the paper, there would be no need for a negative.

The simplest explanation is that Karoly realized the flexibility and endless possibilities he would have at his disposal

if negatives of the “template” photograms were created. It gave him much more control to alter the original central part of the

photogram and add other elements as he experimented.

Above: My recreation of one of Karoly’s Anthropos themes with my cut-out, but now I

Above: My recreation of one of Karoly’s Anthropos themes with my cut-out, but now I

have replaced the cut-out parts, leaving spaces in between for the light to penetrate.

Above: Here is the same set-up as above, but now I have added clouds and stars.

Above: Here is the same set-up as above, but now I have added clouds and stars.

The black stars were cut out from a separate sheet of paper and placed on top with a separate,

longer exposure than the other items to make them darker in order for them to stand out.

Additionally, I added additional exposure gradually to the top half of the image and feathered it by hand

to create a gradation. This is referred to as “edge burning” in traditional darkroom printing.

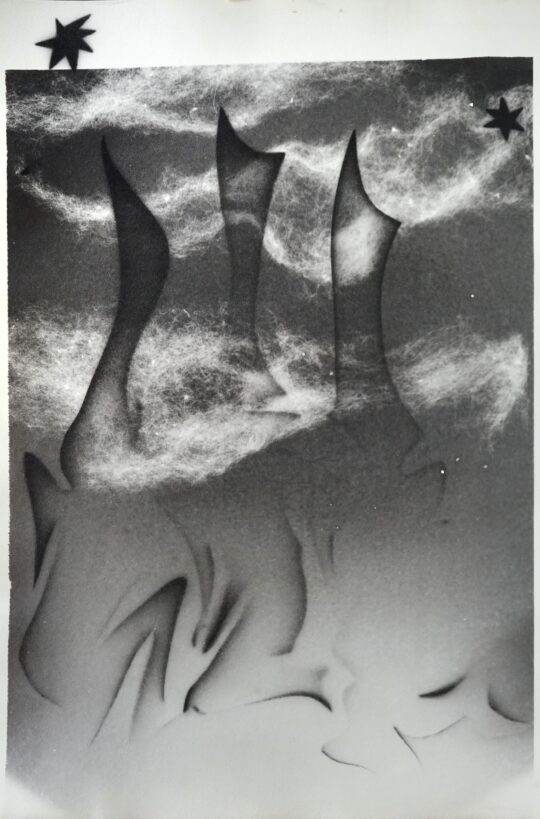

Above: In this version, I removed the cut-out parts of the figures and exposed this print as above.

Above: In this version, I removed the cut-out parts of the figures and exposed this print as above.

This time the white stars were felt necessary, so they were added. You can see the clouds are different, as is

the case in many of Karoly’s prints. I added more edge burning to the top half of the image for added effect.

Above: This variation shows how I can flip the black stars (that were cut out of one large sheet

of black paper), to show up on opposite sides. The stars can change easily; I can put them anywhere I want.

The Karoly Negatives

Karoly used a view camera with “Ansco Supreme Pan” pack film, which was approximately 3.5 x 4.5 inches. The 24 negatives in the collection have been organized into two main groups:

“Template” Negatives: These negatives were produced using Option A as described earlier. Put simply, they are negatives of prints made of the main character or subject in the final photogram. These negatives were put into an enlarger and when projected, they became the light source for the final photogram, instead of simply using white light. I call them template negatives since they serve to create the main parts of the photogram over and over with variations added by the artist.

Copy Negatives: These are copies of final photograms, probably done so Karoly could make variations on the prints in the darkroom process as if they were traditional lens-based images created by a camera.

Printing the Karoly Negatives:

Left: With this original negative, I used its projected image to expose the paper below and added cotton for clouds.

Right: In this version, I added the black stars and replaced the stars made with wax paper with those made with an opaquer paper, allowing them to stand out more.

Thematic Categories of the Karoly Photograms

The photograms are organized by subject matter/concept into the following categories:

- Three Anthropos Characters, with Variations

2. Two Abstracted Figures Opposing Each Other

3. Central Shape with Tendrils

4. Seven Figures

5. Assorted Abstractions

6. Animals and Other Organics

Observations of the Construction of Selected Photograms

The following examples of Karoly’s photograms have been selected to further illustrate his technique:

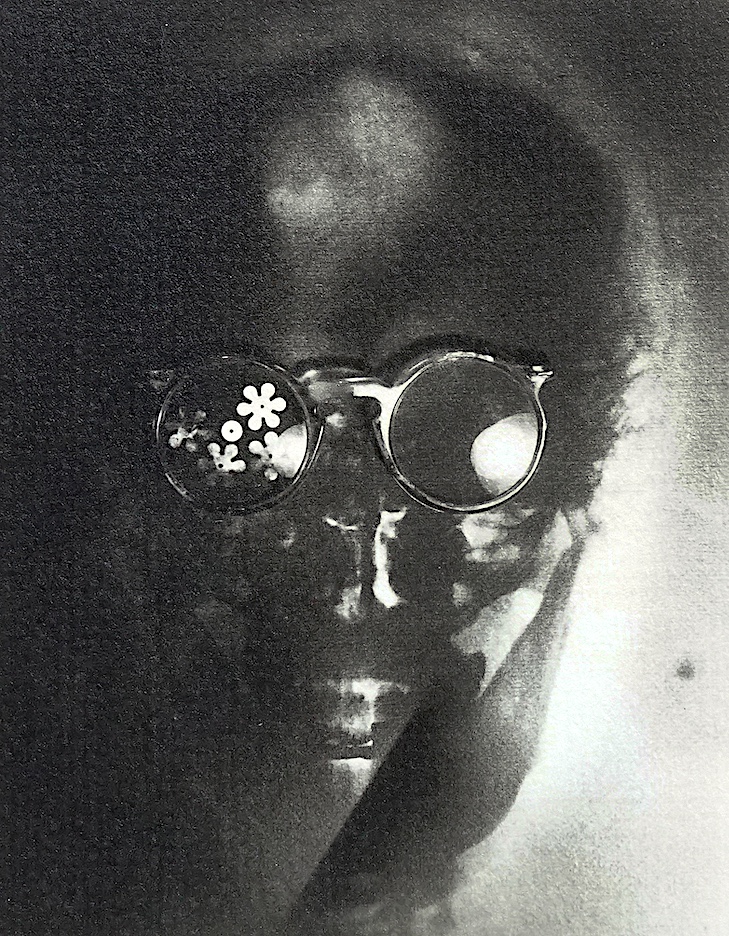

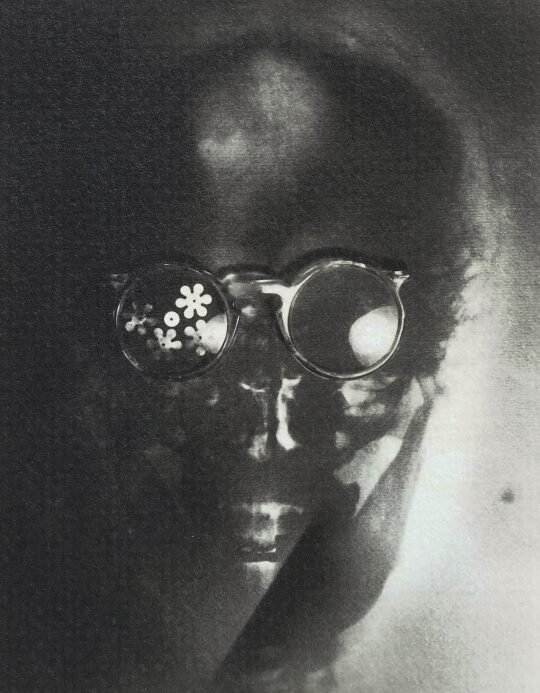

1) No.83 (from the Organics Series, Skull Face with Glasses) 4 x 3 inches

Karoly created this image by starting with an actual X-ray of his own head. In order for the final image to look like an

X-ray (note the dark bones), he would first make a photogram directly from that X-ray. Next, since that image

would be reversed, the print would need to be photographed, the film processed, and the resulting negative printed.

The printed negative is at right. This results in an image with a white background and black bones.

Next, the arms (or temples) of a pair of eyeglasses are removed and laid down on the print. Decorative shapes are added behind

and perhaps on top of the left lens. The resulting hybrid still life/photogram is photographed, the film processed, and the print at left

is the result. Note the reflections of the light source on the right edge of both lenses. The light was placed at the lower right.

Also note his addition of hands in the image. These are most likely real hands held in place during the first phase of creating the

original photogram but could be cut-outs or gloves. Karoly created the glow around the skull through additional exposure of the paper.

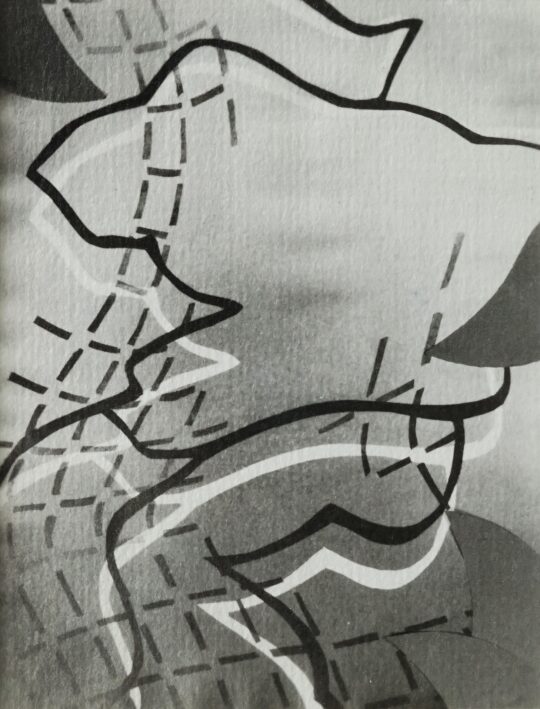

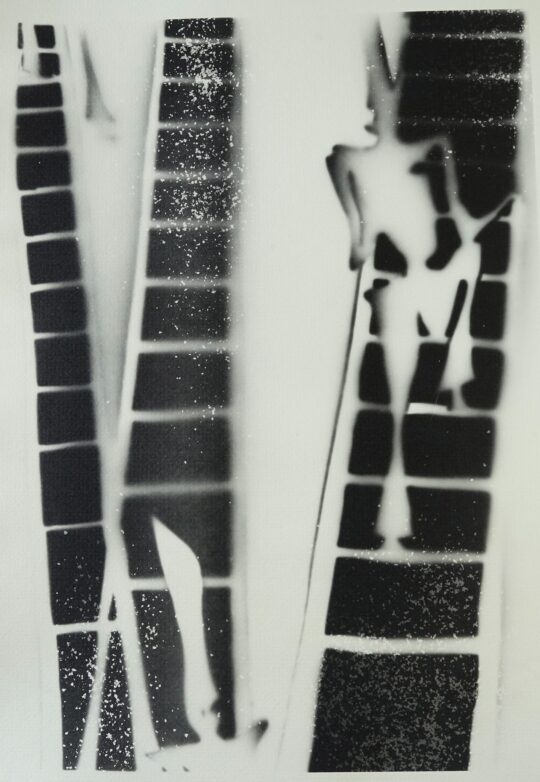

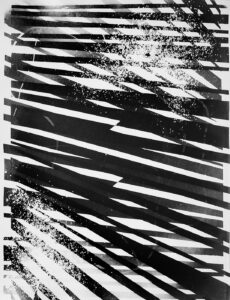

2) Untitled No.64 and Untitled No.63 (from the Anthropos Series) 25 x 9.25 inches

In the two photograms above, one can clearly see that the dramatic horizontal strips going through the image are the same in both.

If this was attempted by simply laying strips down on paper, they would have shifted when removed for developing. Therefore, the background,

as well as the figures themselves, are both from template negatives, one used, and then the other. The variations occur in the thread and/or

fibrous material added as well as adjusting exposure times. Notice the slight variation in the placement of the white wire at the eyes of the

lower figure and the missing left “eye” in the lower figure — another indication of the movement of key parts.

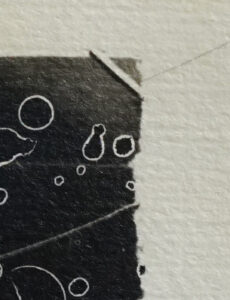

3) No.81 (from the Abstraction Series) 4 x 3 inches

In the close-up below, note the emulsion curling at the bottom edge of this print.

4) No.66 (from the Anthropos Series) 13.25 x 9.25 inches

In this version, the strips have not been used, yet the white wire or string lines remain the same. The fibrous material is more prominent, as are the bubbles or other defects on the glass support.

The tell-tale staple!

Note also the presence of a staple captured at the upper right corner of the print of the photogram at left. At some point in the process, a print was stapled down before being rephotographed.

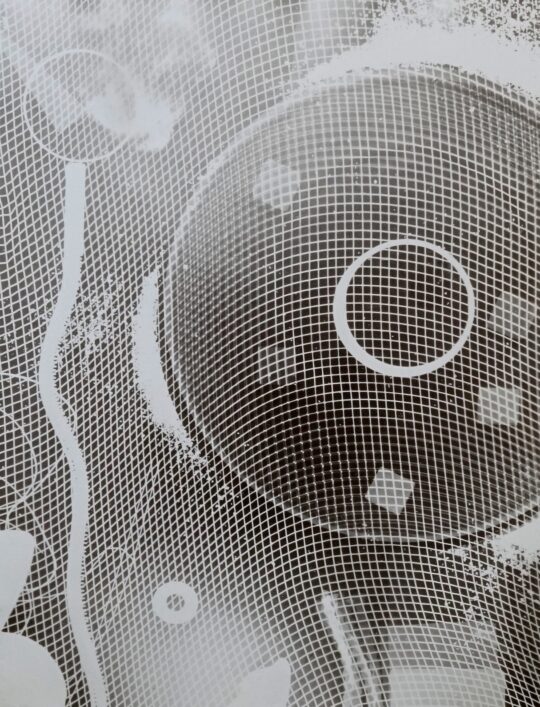

5. No.76 (from the Abstraction Series) 13.25 x 9.25 inches

In this photogram, there is really only one “set” of black

and white stripes running through the image.

First, Karoly added the powder at top and bottom. He then introduced a

projected image of the strips going in one direction, then flipped

the template negative over in the enlarger, and re-exposed the paper. Notice the

overlapping ends of the black strips on the left and right. Also note the powder

is NOT identical, showing that it was an added element that shifted on the

plexiglass or glass during the process.

Concluding Thoughts

Karoly created most of the photograms using the complex techniques described above, often with variations. These processes allowed him more flexibility to create different versions stemming from his original images.

Contemporary photographers such as Michael Flomen and Mary Zompetti use some of these techniques. Flomen uses sheet film to create his initial photogram, then process that film. Zompetti uses a chemigram. The results are photograms on film instead of paper. Now, prints of that photogram negative can be made. In a sense, those prints are copies of the original photogram as well.

About the Author

With over fifty years of experience as a fine art photographer and educator, Terence Falk has exhibited throughout New England and New York. His teaching credentials include institutions such as The International Center of Photography in New York, The Maine Media Workshops, in Rockport, Maine, and The Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. His teaching focuses on his extensive expertise in traditional silver gelatin darkroom printing, historic processes, and contemporary concepts in photography.

With over fifty years of experience as a fine art photographer and educator, Terence Falk has exhibited throughout New England and New York. His teaching credentials include institutions such as The International Center of Photography in New York, The Maine Media Workshops, in Rockport, Maine, and The Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. His teaching focuses on his extensive expertise in traditional silver gelatin darkroom printing, historic processes, and contemporary concepts in photography.

Terence is also regarded as one of the finest printers of exhibition quality black and white photographs. The masters among his clientele have included Richard Avedon, Bruce Davidson, Philippe Halsman, Horst, Mary Ellen Mark, Duane Michals, Inge Morath, and Eva Rubinstein. Awards include an Artist Residency at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts in Sweet Briar, Virginia and The Weir Farm Visiting Artist Fellowship, in Wilton, Connecticut. Institutional group shows include The Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, The Portland Museum of Art in Maine, The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and The Fitchburg Museum of Art in Massachusetts. Institutional solos include The Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockport, Maine.