Abandon in Place

My paintings comment on the melancholy beauty found in relics of our industrial past.

— Anna Held Audette

Connecticut artist Anna Held Audette [1938–2013] discerned loveliness in decline, creating paintings of the disused factories, machines, and scrapyards that are our modern ruins. Her works attest to America’s ascendance and decline as a manufacturing titan. The often-considerable scale of Audette’s paintings, and their depiction of rusting machines in the places where they were made or used, position her compositions somewhere between landscape, still life, and abstraction.

Audette’s art reveals the landscapes Americans have created and consumed over the history of the industrial era with our appetite for making new things, then casting them off. On the architectural “casualties” of the shift away from manufacturing, Audette wrote that “they come from a world of giant industry unaware that it could be slain by David in the form of a computer chip.” Her evocative images find radiant color and mesmerizing forms in unfamiliar, and at times disconcerting, locales where the artist serves as our avatar in approaching behemoth pieces of metal or concrete. Audette defied expectations for women artists that lingered through the end of the 20th century, embracing inhospitable, even hazardous, subjects that included decommissioned ships, airplanes, condemned factories, and even space launch sites—all marvels of modern engineering and the ambition to explore, conquer, and control.

Mourning waste and the decline of industrial might, Audette nevertheless perceived both the transcendent humanity and ingenuity vested in the crafted objects and spaces that caught her eye. Artistically, her careful, incisive observations on canvas reflect the intentionality and deliberation with which she examined the relationship of nature to the manmade. Her attention to the making and unmaking of the industrialized landscape could not be timelier, as is her contemplation of humankind’s detritus in an era when the environment has reached a state as precarious as Audette’s masses of scrap metal and partially demolished factories.

Egypt

Audette was interested in ruins from a young age. Already attentive to history and themes of time’s passage, Audette took a sabbatical from her job teaching drawing and printmaking at Southern Connecticut State University in 1976-77 and traveled to Egypt to study its architecture and sculpture.

She spent the year in Alexandria with her two young daughters and husband Louis. Audette juggled her roles as artist, professor, wife, and mother, often frustrated at the challenge of making art in an environment where meeting the necessities of daily life took all day. Whenever possible the family explored architectural sites that reflected Egypt’s long, layered past of dynastic rule and colonial influences. They encountered contrasts between ancient and modern, with each trip as fascinating as its destination. “The incongruities are marvelous,” Audette wrote to a fellow artist back in New Haven. The perspective gained on both Egypt and America by living abroad proved formative.

Despite security prohibitions, bureaucracy, and cultural barriers that affected where foreigners could travel, the family journeyed to Karnak, Abu Simbel, and other ancient complexes, where Audette took hundreds of photos as inspiration for her drawings and prints. She depicted towering temple columns whose limestone surfaces have been softened by the elements. Her compositions evoke time’s passage and the transformation of Egypt by modernization projects that dammed the Nile in the 1960s for hydro power and flood control. By overlaying transparent forms, dissolving columns into their wavy reflections in the water, or constructing on paper pyramids of wreckage from the World War II battlefield of El Alamein, Audette alludes to the simultaneous awesomeness and instability of human monuments and the tension between history and progress. Musing on these profound encounters, Audette wrote to a former student and friend, “There is much that is mortal in these “immortal” forms.”

Transportation

Drawings of junked cars were Audette’s first foray into studying modes of transportation. She could find them in the woods or at scrapyards, where a chat with the owner opened access. The artist took dozens of photos of cars at various stages of decline and demolition, from full stacked auto bodies to compacted cubes of scrap. She remarked, “There is a certain kind of beauty frequently found in forms which have been created and worked over by great numbers of people . . . Cars and planes have interested me as extremely refined three-dimensional shapes formulated and reformulated by successive generations of designers and technicians. Reworked by the capriciousness of time, they become extraordinarily complex and compelling masses of sculpture.” Reflecting on the centrality of automobiles in American life and their largely unacknowledged toll on the environment, Audette observed: “abandoned cars are the most abundant contribution made by our times to the landscape.”

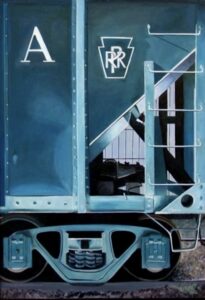

Audette often worked in series, exploring ideas on a particular subject across multiple paintings. While she developed her series on Space Sites consecutively, she returned to others sporadically. Audette put her truck series in this category. She gathered source material from service areas on major highways in Connecticut and elsewhere, photographing as she walked around truck stops that she said could be “almost anywhere in the country.” At other times, she took photos from the front seat of a car as she and her husband Louis drove to survey industrial complexes or navigated speeding semis on roadtrips to visit their daughter in college. Audette’s transportation themes extend as well to sidelined railroad cars at outdoor museums like Steamtown National Historic Park in Scranton, Pennsylvania, places where engines of mobility have come to rest. While no longer capable of movement themselves, the vehicles intrigued her for what she called the “corridor views,” the complex and layered way that one could look across and through these stilled machines to recapture a sense of their former speed and dynamism. Musing on the lost potential of obsolete technologies, she commented, “we haven’t put our money where our mouths are. Romance aside, the fact is that real neglect has caused the terrible decline of a once great transportation system.” At the same time, as her attention to the curved shapes and colors of trains suggests, the artist felt that “machines, especially the ones that are corroded by time and weather, are sculptures.” Audette’s fascination with cars, trucks, and trains—subjects traditionally associated with masculinity—illustrates her unwillingness to align herself with female stereotypes.

Aircraft

Coming off a series of drawings about junked cars, Audette aimed toward a new artistic horizon in her contemplation of idled airplanes. After twenty years of teaching printmaking and drawing at Southern Connecticut State University, the artist was promoted to full Professor in 1980. Perhaps honoring her achievement of a major milestone then attained by few women in the academy, Audette made the leap into painting in the early 1980s as a means of tackling subjects—beginning with aircraft—with a range of colors and on a bigger scale. As a student of printmaking in the 1960s at Yale School of Art and as a woman in the contemporary artworld of those years, Audette seemingly resisted the pressure to produce large works like the paintings of her male classmates Chuck Close, Rackstraw Downes, and Brice Marden. When she arrived at the decision to work big and in paint, it was the result of her own evolving process and inquiry. In works like Fighter Plane, Audette continued to utilize her printmaking expertise by emphasizing the contrast between the dark and light in the sky, and sensitively handling tone in the misty atmosphere over the plane and grass. Reflecting on this transition in her career from printmaker to painter, the artist wrote in 1985 that it was a “change so slow as to be nearly imperceptible, and yet absolutely remarkable. . . [I] find it gratifying to realize that I may eventually be capable of things I cannot even guess at now. . . the sense of my own capabilities has never been stronger.”

The March 1982 Geo magazine article “The Ghost Fleet” attracted the artist to aviation as an artistic subject with its photographs and descriptions of the thousands of aircraft mothballed in the Arizona desert at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. While some of the 3,500 planes are stored until re-entering military, civic, or commercial use, others are retired models that are dismantled so the parts and materials can be recycled or melted down. Audette wrote a series of letters to the Air Force to request access to the yards to make drawings and photographs as studies for future artworks. To reassure them, she explained, “my final work will consist of fantastic combinations of those aircraft, [so] I doubt my efforts will create any security concerns.”

Once at Davis-Monthan in April 1983, she walked past rows of neatly positioned, stored aircraft to the breaking yards. That section of the base appealed to her as a place where workers in an industrial-scale operation deconstructed aircraft that had represented American manufacturing and military prowess from World War II onward. Audette also visited nearby aviation surplus yards, where she saw the Vought F8U-1 that she idealized in Fighter Plane. The artist described finding the greatest visual interest in “the oldest and/or most dilapidated planes,” “that are in the worst shape.” Previously expensive hi-tech marvels, the fragmented aircraft now project vulnerability with their ragged edges, faded paint, and missing parts.

In Nacelle, Audette echoes the round shape and large size of the airplane component in her canvas, as if we are looking directly at the discarded object she encountered at Davis-Monthan’s breaking yards. A nacelle (from the French word for small boat), is a metal enclosure attached to the wing of an aircraft that surrounds parts such as fuel supplies, equipment, and especially engines to streamline the flow of air. Most civilians would never have the opportunity to see a fragment like this up close, but the artist boldly brings us to one. Peering into the nacelle’s circular form sends us down the rabbit hole to a place that feels dystopian with its jumble of wires and a ghostly aircraft on the other side.

Audette acknowledged how seldom planes appear in art, despite how inconceivable travel seems without them. She wrote, “The decay of military planes as opposed to conventional dog fight pictures is virtually nonexistent as a subject. It is a difficult theme because people are troubled both by the need for these planes as well as the thought that they are not invincible.”

Scrap Metal

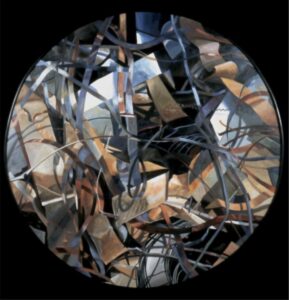

Around 1980, Audette found herself fascinated with the shapes and colors of cars in a rural automobile junkyard. After introducing herself and her artwork to the owner she was welcomed to the property, where she began studying a theme that runs throughout her paintings. The longest series Audette did on one subject was about scrap metal, eventually numbering over twenty canvases. Of her interest in scrap she wrote, “The piles of all different kinds of metal have held a special fascination for me because they contain items in an endless variety of shapes and colors and result in some of the most satisfying combinations of simultaneously representational and abstract energy.”

To Audette, scrapheaps were quintessential products of the modern American technological age, where obsolescence arrived at accelerating speeds. In her files, the artist kept photocopies from designer George Nelson’s 1977 book How to See, which echo her outlook. Nelson noted that in less industrialized parts of the world, things are reused rather than tossed on the scrapheap. He wrote “Junk is the most pervasive product of technological society . . . junk is our ultimate landscape.”

In her scrap compositions, junk fills the frame, becoming a landscape. While Audette’s paintings do not situate the scrapheaps in a wider perspective, her preparatory photos of the Schiavone Metals scrapyard she visited in North Haven, Connecticut, to find subject matter show rusty piles slumping on the bare earth amid dirty puddles. The artist appreciated the environmental dimensions of industrialization’s discards: ruins in their own right, the scrapheaps are also ruining the land they occupy.

Past and present are linked in Audette’s paintings of scrap. Her choice of a round canvas (reminiscent of Italian Renaissance paintings) for Scrap Metal X reflects her determination to contrast naturalistic renderings of the metal scraps with abstract gestures. As she explained, “Apart from what scrap metal says about our culture, painting it also rewarded me on quite another, more formal, level. I have always been interested in subjects that are, on the one hand quite real and recognizable and at the same time have a strong abstract component. Scrap metal imagery provides a particularly successful avenue toward this goal.” In lectures about her work, she highlighted her desire to address both representation and abstraction by comparing the dynamic tension and detail of Scrap Metal X to the balanced visual bustle of Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie (1943–43, Museum of Modern Art).

While abstract in its emphasis on formal structure and immersive cropping, Scrap Metal XVII also depicts objects with a past, evidenced by the damage to their once-intact forms. While these are discards from American industry, Audette discerned resonances between the modern wreckage and the destruction that her parents—originally from Germany and Sweden—had fled when leaving Europe in the 1930s. Growing up amid the European art collection assembled by her father, an art historian, and mother, a paintings conservator, instilled in Audette both an awareness of art history and an appreciation for the effects of time’s passage. The piled cylinders and sun-bleached color palette in Scrap Metal XVII evoke Renaissance artists’ depictions of classical ruins as well as the way that painters John Singer Sargent and Edward Hopper—two of Audette’s favorites—used a range of intense blues to suggest shadows. Scrap Metal XVII was owned by Audette’s father Julius Held, who kept examples of her art in sight of the desk where he worked on art historical scholarship about Netherlandish painters.

How Did the Artist Access Unconventional Places?

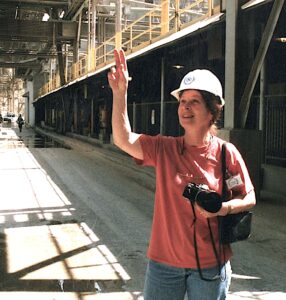

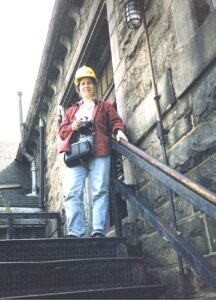

Writing about her paintings of ruined industrial landscapes, Audette characterized them as outcomes of “architectural experiences.” Sometimes she orchestrated those experiences by soliciting an invitation in advance from the owner or caretaker by sending a letter and photos of her work as testaments to her interest and intentions, correspondence typically met with enthusiasm by the recipients. Writing to the town attorney in Seymour, Connecticut, in 1999 for permission to visit a soon-to-be demolished factory, Audette explained she would “need about an hour to take some photographs as the basis for future work,” adding “I have a hard hat and would respect any restricted areas.” On one such factory visit, her host gave Audette a helmet, which she continued to wear on expeditions.

At other times (or as a prelude to sending letters), her husband Louis scouted locales that they visited together, looking for busted fences and factories they could sneak into. Like the “Urbex” or “urban experience” photographers of today in search of similar abandoned industrial subject matter, she roamed inside and out, careful of the often-hazardous condition, and used her camera to record what caught her eye. Audette would bring along photos of her paintings on these expeditions in case the couple was caught and needed to explain their presence. Although they might be escorted off the property, often Anna would leave with the name and phone number of someone who could authorize access. Back in the studio, Audette studied her photographs, tapped her memories of the experience, and selected elements of both to compose her imaginative paintings.

Landscape

“A good part of my fascination with these subjects comes from the altered architectural spaces and peculiar beauty created by massive neglect.”—Anna Held Audette

Nineteenth century artists such as Thomas Cole who made up the first generation of landscape painters in the United States turned their attention to the subject amid concerns about the toll of settlement and industrialization on the country’s wild, undeveloped vistas. Nearly two centuries later, Audette’s paintings reflect the legacy of those profound changes, sharing DNA with depictions by Cole and other members of the Hudson River School whose canvases both celebrated and lamented the loss of idyllic American landscape.

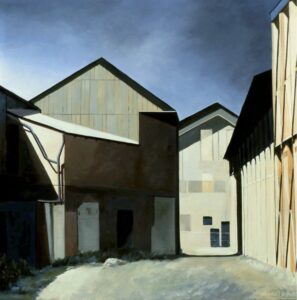

Where nature appears in Audette’s work, it is resurgent through ruptures in the built landscape— the weeds that grow from cracks and the rainwater that pools on concrete. Her places are steeped in human history. We see the story of American geographic and industrial expansion over the 19-20th centuries via the bridges, railroads, and factories on her canvases. Her landscapes are composed of the buildings and objects people have constructed, used, and discarded. Because her landscapes are full of disused “things” humanity has left behind, with no explanation of their origin or purpose, the places can feel enigmatic and inaccessible as if we were encountering them as archaeologists years in the future. Audette embraced this quality of her landscapes, writing “this mystery adds significantly to their impact.” As viewers, we are in these places, but with little clue about how to navigate. A lack of doors or windows, as in Sheds, Bethlehem Steel, stops us in our path, as if we, like the American industrial landscape itself, are at a dead end. But like the artists Charles Sheeler and Edward Hopper (whose work she considered inspirations) Audette deployed blue skies, crisp pervasive lighting, and even a few stray blades of grass in her minimalist landscapes to fill us with nature’s beauty and remind us of the capacity of art to instill a reverence for place.

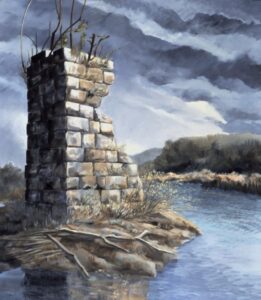

According to her husband Louis, Audette was always on the prowl for intriguing sights and her eye gravitated toward landscapes others overlooked. Her broad knowledge of European and American landscape painting, including her appreciation for Romanticism, are the lenses through which she processed her observations in formulating Harper’s Ferry Abutment, which depicts a ruined bridge pier at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Bridges in Harpers Ferry were destroyed multiple times, both during the Civil War and by floods. The partial stone pier reflected in the river makes visible both human and ecological history in the land, encouraging us to consider two different scales of time. In contrast to Audette’s other landscapes in which built structures predominate, here she has given more emphasis to natural features such as the water, sky, vegetation, and driftwood, which helps cast the bridge fragment in a ruminative mood. Describing her approach to landscape painting, Audette acknowledged the role that the elements play in transforming manmade objects. She wrote, “Time and weather impose new colors and reshape machines and buildings, releasing them from their intended function to acquire a new interest.”

The marine landscape’s salt and humidity accelerate nature’s mellowing effects on the manmade. In the late 1990s, the artist and her husband visited Iceland. Trawler depicts one of the many boats that comprise that country’s large fishing industry. In photos that Audette took to remember the scene, two massive trawlers await maintenance in dry dock, edited down to one in her final painting. The artist’s decision to depict the vessel propped up on shore by itself spouting water from its hold—rather than a more expected view of it afloat—underscores Audette’s ability to make us look at the landscape with fresh eyes unfiltered by notions of what is picturesque.

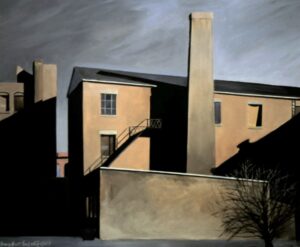

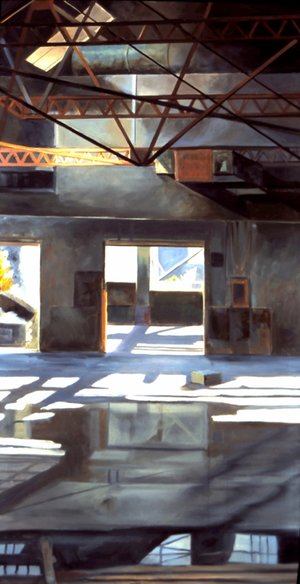

While Audette alludes to specific locations such as Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in her painting titles, she treated her compositions as examples of how the American landscape has been broadly transformed by the expansion and decline of industrial infrastructure. In her factory views, Audette drew attention to the blend of neglect and beauty that haunts these once thriving landscapes. Artist Charles Sheeler photographed and painted renowned pictures of Ford automobile plants, railroads, and industrial machinery between the 1920s and 1940s. Audette found inspiration in his images of active factories without visible workers, where the hushed atmosphere he imparted created a tone of reverence for sprawling marvels of the industrial age.

But observing comparable factories from the 1970s onward made Audette acutely aware of American manufacturing’s decline. Bethlehem Steel, whose sheds she depicted, ceased operation at its Pennsylvania site in the 1990s and declared bankruptcy the year she completed her canvas. The artist recalled of Bethlehem Steel that it no longer operated in its namesake town and that, “Many of the buildings have been torn down.”

Audette’s landscape of the remaining structures shows them abandoned, the once mighty complex now bereft. Audette wrote in relation to this and similar factoryscapes, “They are relics of America’s industrial glory at mid century: great structures erected to support the technologies that shaped the country we now live in. As a painter, I have been inspired by the endless examples in which the triumphs of industry turn out to be just a moment away from obsolescence, casualties of our rapid technological evolution.”

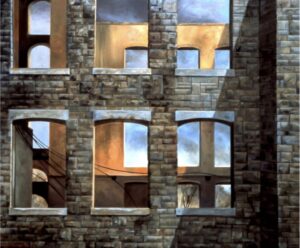

Once closed to the elements, factory buildings like the former home of manufacturer Seymour Specialty Wire in Seymour, Connecticut, take a step closer to the landscape through their broken windows and caving roofs that admit rain. Shown on Audette’s canvas not long before its demolition, the plant produced copper and brass wire. In the 1960s it also processed uranium for defense use, leaving behind contamination (and a legacy of environmental injustice) that lingers in so many defunct industrial properties and continues to affect nearby inhabitants. The tall vertical composition of Seymour Specialty Wire entices us to admire the lofty space, which served in 1991 as the setting for Other People’s Money, a movie about the owner of an obsolete New England manufacturer trying to fend off a Wall Street takeover. In her paintings, Audette, not unlike the artist Edward Hopper, acknowledges the cinematic character of such abandoned places with their hinted stories.

Audette’s landscape paintings catalogue America’s once-thriving industrial infrastructure. Baltic Mills depicts the remnants of what was once the largest textile mill in the country, located in Sprague, Connecticut. Opened in 1857, the complex experienced booms and busts from 1873 until textile production ended in the 1960s. The town sought to re-develop the complex, which Audette and her husband had visited. In 1999, Baltic Mills burned in an arson fire, leaving only the stalwart masonry shell of Building Number 10. Always fascinated by the complexity of views through structures, Audette delineates not only the terracottas and blues of the exterior granite but also the glowing, wrecked interior apparent through the evenly-spaced window openings. Commenting on “closed northeastern factories” like Baltic Mills, Audette remarked, “These are the remains of collapsed power. They have a strength, grace, and sadness that is both eloquent and impenetrable.”

While declining factories are a common sight in New England cities and towns, Audette infuses a sense of place into Old New Haven not through architecture but through lighting. She wrote, “As a coastal city, New Haven often has dramatic light effects.” Audette gave that characteristic local illumination geometric form, contrasting the bright terracotta-colored walls with stark shadows cast by nearby buildings. Combined with the bare branches in the foreground, the steeply angled lighting suggests both the late season and time of day, setting an elegiac mood for the former cigar factory.

Old New Haven exemplifies Audette’s appreciation for both the urban streetscapes of Edward Hopper and the modernist Charles Sheeler’s photos and paintings of factories from the 1920s to the 1940s. In a 1990 artist statement written in the third person she quoted Sheeler in relation to her approach: “While her works are representational, she is equally concerned with their abstract qualities. She shares this outlook with Charles Sheeler, an artist she admires, who also felt ‘that a picture could have incorporated in it the structural design implied in abstraction and be presented in a wholly realistic manner.’”

Ruins

Speaking to the Society for Industrial Archaeology in 2000, Audette described her concerns as a painter to be “the ruins of our time—remains of the twentieth century at its close.” While based on her observations of America’s waning industrial infrastructure, her depictions of ruins were very much informed by her knowledge of art history. She took inspiration from 18th-century European artists like printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi and painter Hubert Robert, who glorified re-discovered Greek and Roman ruins. For her Demolition series based on the destruction of the Winchester Firearms factory in New Haven, Audette even invoked Robert’s name in the subtitle of the first paintings on that theme (now in the collection of the New Britain Museum of American Art). In Demolition II, metal rebar that once strengthened the building’s concrete pillars now hangs exposed, like vines overtaking the abandoned structure. Remnants of painted surfaces, windowpanes, and chain-link fence are ghosts of the factory’s former life, for which the arist serves as witness in its final moments. Audette also looked to 19th-century gothic revival artists and architects, who incorporated ruined buildings into their compositions or even constructed new “ruins” as objects for romantic contemplation. Then, as now, ruins remind us that life is fleeting. The incompleteness of ruins offers viewers the power and pleasure of using their imaginations to fantasize about what once was, what is missing and why—compelling considerations that have helped give rise in the past decade to trends such as ruin tourism and urban exploration photography (“Urbex”) depicting abandoned properties.

“In earlier civilizations,” Audette wrote, “People pondered what could still be seen of ancient palaces, great public buildings and places of worship. The architecture of the everyday working world disappeared totally without any record to commemorate its importance. How different the fate of such edifices today.” For her, paintings of derelict factories and heaps of obsolete parts “record the passing of our industrial landscape—casualties of our accelerating technological evolution.” A process that once took centuries now concludes in a generation or less, surrounding people who still remember the vital role of these buildings in their communities with what she echoed Dead Tech author Rolf Steinberg in labeling “the antique cities of tomorrow.” By calling attention to “unnoticed, mute reminders of where we were not so long ago,” Audette honors the dignity and even grandeur of abandoned places and objects that once embodied America’s aspirations and accomplishments. At the same time, her paintings leave us with the ominous and ever more urgent question: If these structures and the culture that produced them are ruined and no longer meet our economic or social needs, what can?

Audette’s paintings of scrapyards bring together many aspects of her interest in ruins. Like archaeological fragments, the bits and pieces in Scrap Metal V are puzzling and suggest countless stories to be told—what were they, who made them, how old are they, and how did they arrive here?

While conscious of scrapheaps’ ecological impact, depicting them also allowed Audette to address the romance of time’s passage, as have other artists fascinated with ruins. She identified the “peculiar beauty created by massive neglect,” and observed that “The effects of weather frequently give these ruins more color than they originally possessed, and decay may make two formerly identical forms eventually appear quite different from another.” Audette’s color palette includes luminous pigments such as yellow ochre, cadmium orange, and cobalt turquoise, imparting a glow and hint of preciousness to these aged remnants.

Still Life

“I often contemplate and admire large, aging engineering structures that have endured beyond their time such as the Hoover Dam, retired ships, or obsolete bridges. Occasionally similar qualities of grace and strength are manifest in much smaller objects: a railroad coupling, a carburetor, or plows,” Audette wrote. “Even when our technology is reduced to mere scrap, the pieces remain eloquent.”

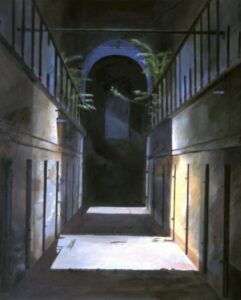

Whether depicting tools, car parts, moored ships, or buildings, Audette looked closely at the physical world with attention to qualities of line, form, volume, and shadow. By insisting on the material presence of objects, she imparts a monumentality to ordinary items that suggests the consideration, craft, and human effort that went into them. Audette’s intense focus imparts stillness, but not emptiness. Spaces like the crumbling hallway of Eastern State Penitentiary give rise to new life in the form of sprouting weeds. The quiet atmosphere of her works recalls the hushed mood of paintings by Charles Sheeler, whose unpopulated factory scenes and views of domestic interiors Audette admired. She also felt a kinship with artist Walter Tandy Murch (1907–1967), whose still lifes of everyday objects and machines hover between Magic Realism, Realism, and Surrealism.

Audette described her decision to paint ’49 Cadillac Fuel Pump as the result of epiphany while watching her husband Louis restore the family’s inherited convertible: “Just as I find meaning in large ordinary architecture, I am attracted to relatively small machine parts. This is a fuel pump for a ’49 Cadillac. It was sitting on the ground while my husband was working on the car. I immediately saw the wonderful possibilities of this little piece of glass and metal sculpture. So the car repair had to wait until I had the fuel pump on canvas.”

Audette positions the pump on a tabletop, imparting monumentality to an object considerably less than a foot high. Centering it in the composition and bathing it in strong light allows her to remind us that even factory-made objects embody histories of care and dedicated work that still seem to emanate from them. The sense of reverence is heightened by her carefully dramatic lighting of the piece, which she indicated “came out of my memory of some early nineteenth century pictures of German interiors.”

Discarded farm machinery provided intriguing subject matter for still lifes such as Corn Combine. Observed in this instance on an Indiana farm, the corn combine offered the appeal of rusting painted surfaces as well as intricate parts. The artist focuses so closely upon wheels, belts, and wires that the machine’s function as a harvester is hard to recognize. In an act reminiscent of the Surrealists who incorporated machine imagery into their works, Audette balances forms along with light and dark in an all-over composition in which viewer orientation is no longer relevant. To distance herself from representing only what she observed, the artist worked not only from her color photograph of the green machine but also from a color negative in which the hues seen with the naked eye are reversed into the red shades predominant here. What began as a still life of a corn combine morphs through Audette’s vision into full-fledged abstraction.

Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia opened in 1829 as the architectural embodiment of Quaker ideals of rehabilitation, constructed on an industrial scale. To encourage reflection prisoners were housed alone, in solitary confinement cells. Although since designated a National Historic Landmark, the complex was abandoned in 1971 and remains a ruin.

Audette had long admired 18th-century printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s series Imaginary Prisons for its depictions of haunting, ambiguous, and mostly depopulated architecture. Sensing the potential of Eastern State, she wrote to the director to arrange an “off-season visit,” and to her satisfaction was handed keys for a self-guided tour. Remarking to her host that she had found the complex “fantastic and overwhelming” Audette composed a series of paintings, including Eastern State II, from which she explained that she “removed virtually all signs indicating the exact nature of the interiors because I wanted the images to communicate a more general sense of melancholy, decay, and abandonment.” The result—especially appropriate for a former prison—hovers between landscape and still life.

Space Sites

Audette’s interest in NASA launch sites was stimulated by photographs of Cape Canaveral complexes 19 and 34 that she saw in the 1982 Sierra Club book Dead Tech: A Guide to the Archaeology of Tomorrow. She and her husband made a road trip to Florida in the 1980s during which she took photographs of NASA’s abandoned architecture. Those studies became the basis of a series of paintings.

Audette gathered ideas from decommissioned facilities around Kennedy Space Center. She described her objective as “to learn the visual vocabulary of a place and then create my own vision from the experience.” She toured the infrastructure NASA built on scrubby coastal land beginning in the 1950s. Erected to further Americans’ quest to reach, explore, and dominate outer space during the Cold War, the concrete walls and metal armatures that once supported fire-spewing rockets on groundbreaking journeys beyond Earth’s atmosphere were crumbling and rusted by the 1980s. With NASA’s preference for progress over preservation, and because of their massive size, the US government marked many of the structures “Abandon in Place,” erecting new ones for subsequent missions rather than repurposing old complexes. In what she called “fantasy,” Audette depicted the austere geometries of the obsolete space sites weathering under the harsh Florida sun. According to the artist, their strangeness prompts us to ask, “Are we contemplating ancient ruins or the otherworldly architecture of newly discovered planets?”

In 1989 Audette requested special access to Cape Canaveral from the NASA Art Program’s administrator and in April 1991, she was accepted into the NASA Art Program. Along with several commercial artists, she was invited to view the launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis (STS-37) at Cape Canaveral (the first launch attempt was scrubbed). As part of the program, she undertook a commission for a painting of an abandoned rocket transporter that became part of NASA’s permanent collection.

Machinery

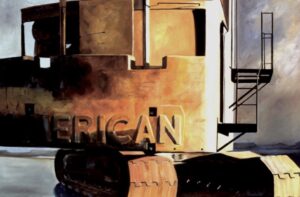

In Audette’s work, machines take many forms, from cranes to factory ventilating systems to metal shredders. As a draftsman and painter always thinking about and tinkering with the parts of a composition and how they fit together to create a whole, she had an eye for the complex relationships and interconnections that are as inherent to machinery as they are to art. She admired the machine aesthetics of French artist Fernand Léger, and the smooth brushwork and industrial imagery favored by the American Precisionist Charles Sheeler, which she echoed in her own depictions of mechanical objects. Like those artists, Audette concentrated on machines at rest, when their shapes and colors are most apparent and their movement quieted.

Since her machines are still, the artist is able to show them to us up close. The proximity is exciting, but also a bit mysterious—who let us near these behemoths, and will they come to life? Through research, letters, and calls (or sometimes by just stepping through a broken fence), Audette arranged with the owners of industrial properties to get access. As a woman interested in machines since childhood, she put herself in places normally limited to men in hardhats so she could make sketches and take photos from which to work. Audette’s insistence on depicting mechanical subject matter that has traditionally been gendered as male speaks to her fearless pursuit of her artistic interests, regardless of conventional expectations for women painters. The understated mood of her finished canvases masks the boldness and initiative she demonstrated to make them.

Audette’s machines often came from scrapyards or construction material suppliers like Suzio Traprock (now Suzio York Hill Company), in Waterbury, where she found the idled railroad maintenance equipment depicted in Crane. She viewed the rusting machine in metaphorical terms, saying “It became for me a symbol of the demise of American heavy industry—almost a memorial of sorts. People have asked me about the importance of inscriptions in my paintings. In some I make them illegible because they either add nothing or detract from the main idea. Here ‘American’ is bold and clear because the subject is about our country.”

Audette saw the machine on which she based Shredder Deck at an automobile shredding plant in Troy, New York. Given the artist’s fascination with the breakdown of buildings and manufactured objects, the shredder is an especially apt subject. Unlike the machines and factories in her other works, which produced goods over many decades, the shredder does not make, it destroys. For Audette, the heaps of scrap represented the dismantling of an order tied to the function of these manmade things, and the introduction of a different system of organization, by metal type. The shredder deconstructs recognizable objects, turning them into raw materials for recycling.

Audette sets up a subtle dissonance in this painting, choosing a limited color palette that imparts a sense of harmony to this otherwise destructive machine.

Audette’s interest in machinery defied lingering gender stereotypes. At the same time it was also a fascination she shared with her husband Louis, whom she met while a student at Yale School of Art. In 1989, as a joint anniversary and birthday celebration, Anna gave Louis a trip through the Erie Canal Locks in western New York.

Bascule Bridge originated in that experience, drawing upon photos the artist took of the bascule- type drawbridge for railroad traffic across the canal at Tonawanda. She observed the bridge from a canal boat as they passed underneath. Rather than compose a view of the entire span Audette focuses on the mechanism of the masonry pier, metal girders, and massive concrete weight that enables the roadway to pivot up for boats when needed. Although the bridge is closed in the painting, her placement of it against the blue sky reminds us of its amazing capacity to tilt into the air.

Suisun Bay

Suisun Bay at the northern end of the greater San Francisco Bay estuary offered the artist inspiration for numerous paintings devoted to the old ships moored there. Audette’s Suisun Bay series came about through recommendations from colleagues who knew of her interest in what she deemed “large and sometimes passing technology.” Following her successful track record of obtaining access to intriguing subject matter at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Cape Canaveral, she contacted the US Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration in 1994 to pursue her interest in depicting the Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet. During the height of the Cold War the waterway was home to 500 military and civilian vessels mothballed in the event of national emergency. Some were cargo carriers made obsolete by the development of container ships, and others had played roles in historical events such as the evacuation of Saigon.

Audette made trips over two years to view the so-called “ghost fleet” of hulking ships moored close together, their hulls disintegrating in a slow-motion environmental disaster. On the first visit, with the help of a pilot in a tender, she photographed the Navy boats and freighters from afar, interested in their repeating patterns and crisp edges despite the misty marine atmosphere. Thanking her hosts for such a “special opportunity,” she wrote that she found the ships “impressive and moving.” In 1995, she returned to study the fleet up close in foreshortened compositions focused on rudders and silent propeller blades projecting at the water line. While her hosts enabled her to go on deck, she preferred the view from the water.

Like the artist Charles Sheeler, whose Precisionist treatments of form and light she embraced, Audette magnifies and crops her compositions with nearly abstract results. She depicts parts of ships rather than whole vessels whose scale exceeds easy comprehension, and treats shadows as bold shapes in their own right. Here as in many of her other series, the artist calls our attention to industrial technology’s limited life span and lack of preservation. The Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet was dismantled by 2017 to eliminate ecological damage from fuel leaking and toxic paint flaking from the ships.

Infrastructure

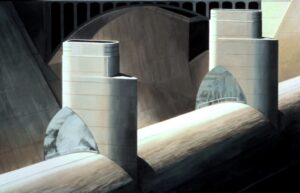

American ambitions in the 19th and 20th centuries spurred major infrastructure-building initiatives such as the railroads, highways, dams, and bridges that modernized millions of lives during that period. New Haven, where Audette settled in the 1960s after attending Yale School of Art, had undergone urban renewal that replaced whole neighborhoods with a network of highways and garages. Audette’s 1976–77 sabbatical in Egypt took place at a moment when efforts culminated to dam the Nile, sacrificing ancient heritage sites.

Witnessing the effect of infrastructure growth first-hand, the artist returned to America with an eye toward similarly big projects here. Updating the work of Charles Sheeler, whose “Power” series for Fortune magazine’s December 1940 issue depicted modern infrastructure triumphs, Audette found appeal in “large, aging engineering structures that have endured beyond their time, such as the Hoover Dam.” As infrastructure, the Hoover Dam enabled industrial, agricultural, and residential development in California, Nevada, and Arizona, but its function is now endangered by climate change that has brought water to its lowest levels ever.

Through her travels, Audette observed the extent of America’s infrastructure as it weaves together the cities and towns it shapes and sustains. The artist wrote the following about Overpass: “The idea for this painting came to me as I was riding the train to New York. Shortly before the city begins, the train goes through several underpasses. The image was made essentially from memory and quick notes so it does not represent any one particular place. The distantly Italian quality of the scene is not entirely accidental.” Audette’s comment nods to the classical Roman innovation of concrete and to precedents in art history for depicting forests of sturdy columns. To maintain that timeless mood in an otherwise modern post-industrial landscape, she opts for the elevated roadway’s quiet underside rather than the bustling traffic lanes above.

By showing us the Hoover Dam’s barren concrete, or the gritty armature of the highway in Overpass as Audette saw it from a passing commuter railcar, the artist suggests the vulnerability of infrastructure originally intended to modernize and improve American life.

Conclusion

Retiring from teaching in 1997, Audette flourished artistically for a decade until she began showing the effects of Fronto-Temporal Degeneration, a form of dementia. With the help of a former student she returned to the studio, using as inspiration the many photographs she had once taken of industrial sites. Her drive to create remained strong and she produced over 100 new artworks during that period. Audette died on June 9, 2013, but her art and role as a cherished mentor to students endure. Beginning nearly fifty years ago, Audette created visual awareness of postindustrial conditions that drew upon both her knowledge of art history and her observations of contemporary American culture. As the 21st century unfolds, the worlds she depicted hold a mirror to our own.

— Amy Kurtz Lansing, Curator, The Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Conn., September 2023

The exhibition catalogue from which this essay was extracted is reprinted here courtesy of the author and Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut. It was originally published for the museum’s solo exhibition — Abandon in Place: The Worlds of Anna Audette — from Sept 30, 2023 – Jan 28, 2024.

The broadest scope of Audette’s paintings may be found on the estate’s website, AnnaHeldAudette

Biography

Audette was the daughter of cultured émigrés who fled Nazism in the 1930s. Her father, Barnard College Professor Julius Held, was a prominent expert on 16th- and 17th- century Dutch and Flemish masters, and her mother, Ingrid-Märta Pettersson, was an art conservator at the New York Historical Society. Audette grew up surrounded by historic European art, both at home and on research trips with her father. Her early artwork reflects her engagement with the European canon through the media of drawing and printmaking, which she studied with artist Leonard Baskin at Smith College, graduating in 1960 as an art history major. She considered following her mother into art conservation, training for a semester at NYU. But recognizing her preference for artmaking, she pursued an MFA (1964) at Yale School of Art with the renowned printmaker Gabor Peterdi and the color expert Josef Albers.

For the next two decades, Audette dedicated herself to printmaking and drawing, which she taught at Southern Connecticut State University as one of only a few women faculty (Yale School of Art had none until two years after her graduation). Summers in Vermont at the home her family had owned since her childhood fostered further artistic development. In the early 1980s, she found new creative avenues in painting, which she pursued for the rest of her career. Audette’s quest for her own artistic expression paired with her long experience as a teacher and mentor to generations of students prepared her to author The Blank Canvas: Inviting the Muse (1993), a widely used book about developing creative inspiration. The artist’s work is represented in private and public collections, including the Rijksmuseum, the National Gallery of Science, NASA, the National Gallery of Art, the Yale University Art Gallery, New Britain Museum of American Art, the Mattatuck Museum, the Florence Griswold Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rust and Sheen

-

DETAILS

DETAILSGold Tractor, 1996

42 x 40 inches (106.68 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFarm Junk, 1999

40 x 38 inches (101.6 x 96.52 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScrap Metal XI, 1994

35 x 46 inches (88.9 x 116.84 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlue Truck, 2000

24 x 40 inches (60.96 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSCorn Combine, 1992

46 x 67 inches (116.84 x 170.18 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFirewall, 2005

18 x 32 inches (45.72 x 81.28 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScrap Metal IX, 1992

60 x 56 inches (152.4 x 142.24 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScrap Metal XX, 1997

40 x 60 inches (101.6 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScrap Metal XVI, 1996

52 x 40 inches (132.08 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSuisun Bay VII, 1995

28 x 31 inches (71.12 x 78.74 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSuisun Bay XI, 1995

40 x 40 inches (101.6 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Ships, 1994

40 x 28 inches (101.6 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMachine Room, 2003

26 x 40 inches (66.04 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScrap Metal XXI, 1998

20 x 50 inches (50.8 x 127 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSFarm Machinery, 2000

38 x 40 inches (96.52 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWater Pump, 1999

22 x 42 inches (55.88 x 106.68 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSScrap Metal I, 1989

28 x 60 inches (71.12 x 152.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWings and Tails, 1984

18 x 12 inches (45.72 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSU574 (Bulldozer), 2004

42 x 28 inches (106.68 x 71.12 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSDishes in Sand, 1998

36 x 26 inches (91.44 x 66.04 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPipes Under Sloss Gas Ovens, 2002

42 x 24 inches (106.68 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSShelton Factory Interior, 2005

50 x 36 inches (127 x 91.44 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTwo Box Cars at Bellows Falls, 2005

44 x 40 inches (111.76 x 101.6 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSeymour Specialty Wire, 2000

50 x 26 inches (127 x 66.04 cm)