Rediscovering Aage Hogfeldt, Founder of an Avant Arts Colony

Aage Victor Hogfeldt was born on July 30, 1925 in Skjern, a town on the west coast of Denmark. In 1928, when he was three years old, his parents emigrated to the United States, settling in West Haven, Connecticut. In 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression, the family lost their home but luckily found work at Knudsen’s, a large Danish dairy farm in North Haven. Here, the young Hogfeldt fed the chickens before going to school. At the 1938 World’s Fair in New York, the thirteen-year-old with a strong artistic bent was profoundly affected when he saw the exhibitions of propaganda posters exhibited by the Fascist, Nazi, and Communist regimes. He found the inherent propaganda of this new form of “socialist realist” art repulsive.

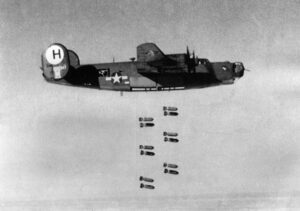

Hogfeldt was doubly repulsed in 1940 when the German army invaded Denmark. Seven months later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and World War II erupted in both the Pacific and European Theatres. As a first-generation American with many relatives in Denmark subject to Nazi control, he was so compelled to fight that in 1942, at the end of his junior year in high school, he put his education on hiatus and enlisted with the US Army Air Force. At training camp in Colorado, he learned to fire a machine-gun mounted atop a truck as it weaved across rough terrain. He thought he would be assigned to a B-17 Flying Fortress — immortalized in the 2024 docudrama television series, Masters of the Air. But by 1943 a new bomber heavier and faster than the B-17 was just being released: the B-24 Liberator. Carrying a crew of ten, it could deliver twice the payload and could fly much farther. Production quickly ramped up at five U.S. factories and at their peak the new bomber recognized for its massive 110-foot wingspan was coming off the assembly lines at the rate of one per hour. In November 1943, eighteen-year-old Hogfeldt first met his crewmates at the new airfield in Bungay, Suffolk, on England’s east coast. They were part of the 706th Bomb Squadron of B-24 Liberators, part of the 446th Bombardment Group of the 8th Army Air Force. The 446th — known as “The Bungay Bukaroos” — was assigned to the 20th Combat Bombardment Wing. The vertical tail stabilizers of these B-24s tail bore the distinctive code of a big “H” within a white circle.

Hogfeldt held a most dangerous position on his B-24 Liberator bomber. He was the nose-gunner wielding twin .50-caliber Browning M2 machine guns. His job was to shoot down the German Luftwaffe fighters attacking “Hot Shot Charlie,” his B-24. (The misspelling of “Charlie” as “Charle” was never corrected). The B-24 had quickly become known interchangeably as “the pregnant duck” for its heavy weight and “the flying coffin” because of its lack of maneuverability made it vulnerable. The odds of returning alive were 50-50. Hogfeldt and his crew made many strategic bombing sorties directly across the North Sea, hitting German positions in Denmark and Holland. On his 16th mission, after heavy flak destroyed one of its engines the B-24 flipped upside-down and spiraled straight down under tremendous G-force that pinned the crew to the floor. The severe dive also caused the other three engines to quit. Miraculously, the pilot managed to restart two engines and pulled out of the dive at the last possible moment. They barely made it back to a base in Scotland, and “Hot Shot Charlie” had to be scrapped. This harrowing event was featured on Oliver North’s documentary television series, “War Stories” (2006). An episode called “Liberators: The B-24 Bomber Boys” featured Hogfeldt and his crew.

They were lauded for destroying U-boat installations, the port of in Bremen, and major factory centers for that supplied chemicals, ball-bearings, and airplane engines for the Reich’s war machine. They even supported the D-Day invasion of Normandy in June 1944 by attacking German bridges, airfields, and transportation hubs in France. They also dropped supplies to the ground forces in France. Six months later, Hogfeldt’s bomber was shot down and crash-landed behind enemy lines in Belgium just as German Field Marshal von Rundsedt was mounting his troops’ offensive during the Battle of the Bulge. Hogfeldt was listed as missing in action, but for several weeks he was evading German capture until the underground helped him finally escape.

Defying all odds, Hogfeldt lived to tell of flying an extraordinary twenty-seven combat missions in “the flying coffin” from December 1943 until his last combat mission at the end of April 1945, attacking a bridge near Salzburg. Less than two weeks later, the German Third Reich unconditionally surrendered in Reims, France. Hogfeldt returned home in June and completed his high school education. In the Fall of 1946, he continued to pursue fine art at Yale University under Josef Albers [1888-1976] and art history under Vincent Scully — both of whom influenced generations of students. In a final salute to his experiences with the Air Force, he painted a still life of meaningful objects: It tells us his nickname was “Hypo” Högfeldt and his rank was that of Staff Sergeant. At top center he hung his leather flight cap and oxygen mask. Beneath them is a leather packet of maps that was certainly used after he crashed-landed in Belgium. At top center, he painted a photograph of himself positioned as the nose gunner. Finally, he laid his five ribbon bars in the foreground.

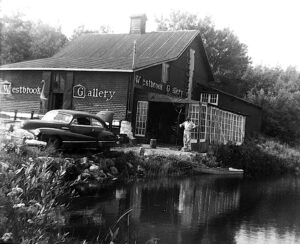

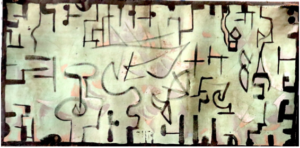

Shortly after earning an MFA in 1951, Hogfeldt left both the war and the university behind, travelling for several years up the New England coast to Maine, painting watercolor shorescapes. Somewhere along the way he conceived of creating an artists’ colony as a reaction to the New York art establishment that he and his Yale friends regarded as flooded with high-brow pseudo-intellectuals. In 1956, his new mission became centered in an old icehouse by a pond on Route 1 in Westbrook, Connecticut, which he converted into an art gallery. In addition to being the gallery’s impresario, Hogfeldt produced oil paintings as well as large welded metal sculpture in a lyric abstract style. He had access to metal scrap for welding his sculptures because for twenty-five years he worked for the Armstrong Tire company (later Pirelli) in New Haven.

The artist’s son, Victor, recalls, “My father found form and substance for artistic flights of fancy in serendipitous visual situations of all types. For example, as a ten-year-old, I once scraped some empty mud wasp nests off a wall in a backroom of the Westbrook Gallery, thinking that I had done something useful and praiseworthy. Instead, my father upbraided me for destroying something visually complex and beautiful. On occasion, if I attempted to straighten out a crooked or misshapen painting frame, he would remark that I should have left the frame alone because the painting ‘deserved’ to have an amusing frame. On the many occasions when I asked him about the ‘meaning’ of a particular work, he would say that it was simply meant to ‘amuse and delight the eye.’ That philosophy seemed to embody his entire raison d’etre for all visual art.”

With Hogfeldt’s creative energy, the Westbrook Gallery thrived during until the mid 1960s, attracting many graduates of Yale’s School of Art. In addition, graduates of the Yale School of Music and the Hartt School of Music (in Hartford) frequently performed chamber music and modern dance. The names of the painters and sculptors, although accomplished, are not well-known today, largely because they eschewed the commercial task of promoting their art. William Kent [1919-2012] had studied at the Yale School of Music during the 1940s but became a master carver in wood and inventor of the slate print. William Skardon [1923-1983] was an expressive figurativist painter. Leo Jensen [1926–1919] created fantastical sculptures in metal. W. Christian Sidenius, who founded the Lumia Theatre in Newtown, wrote “Lumia Kinetic Art with Music: My Theatre of Light” (Leonardo, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1982). David T.S. Jones [1925-1996] was a painter, sculptor, and composer who became director of the Gertrude Herbert Art Institute in Augusta, Georgia. In 1954, he collaborated with Kent to create the first “Slideoperas,” which were presented within the main gallery. Their performances, such as “The Philistine Traveler” and “Oedipus Rex” integrated music, poetry, and Jones’s paintings.

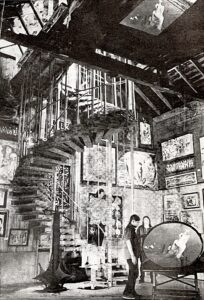

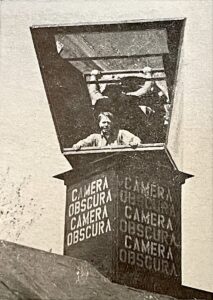

In 1962, Hogfeldt built what he described as “the world’s only 3-position camera obscura.” For position #1, he invited people to ascend a magnificent spiral staircase he made from industrial wooden pallets, bolted together and suspended by aircraft cable. At the top, one entered into the loft camera box, which turned on a revolving mirrored turret. The surrounding aerial view was reflected as a motion picture on an eight-foot circular tabletop on the gallery floor below. For position #2, the same pictures could be seen on a fine screen stretched high above the circular table. For position #3, a large mirror on the floor picked up the motion picture again, this time from the overhead screen.

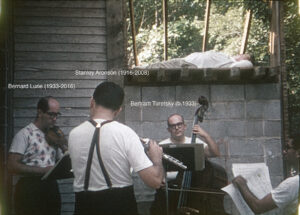

The vibrant Westbrook Gallery enjoyed favorable reviews during its first ten years, attracting the attention of critics writing for The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune. It even captured the interest of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, who in 1962 met with Hogfeldt to explore working together. From the Juilliard School of Music in New York came Teo Macero, a saxophonist who would become one of the most influential jazz record producers. From the University of Hartford came Bert Turetzky, a contrabassist virtuoso who became a prominent composer, joined by his wife, Nancy Turetsky, the flutist.

Other musical members of the group included Bernard Lurie, a professor of violin at the Hartt School of Music and later Concertmaster of the Hartford Symphony and Connecticut Opera Orchestras; plus, the pianist Samual Yaffe [1907–1980] who later taught Music Theory. Also joining them were the Gruppe brothers, master cellist Paolo and Camille, a violinist — both brothers of the famed Rockport painter, Emile. Rheta Naylor (later Smith) played the oboe and later taught in Philadelphia. The Dutch composer and clarinetist, Walter Hekster, performed in the Netherlands Wind Ensemble as well as the Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, and became widely published. He was joined by his wife, the bassoonist, Alice Hekster-van Leuvan.

Few of the painters and sculptors pursued gallery representation or museums. True to their original intentions, it appears that none of them joined arts organizations or clubs outside this spirited community of friends. However, by the late 1960s, Hogfeldt’s Yale colleagues had largely dispersed in pursuit of their careers, leaving their founder on his own. Both an abstract expressionist and surrealist painter at heart, by the mid 1970s he had transitioned to becoming a contemporary folk artist whose style was intentionally humorous and quintessentially kitsch. The gallery became a surreal fantasy environment inhabited by hundreds of figurative sculptures of cats, dogs, and clown busts molded in concrete. Most of the creatures in his menagerie had glass marbles for eyes and many were painted.

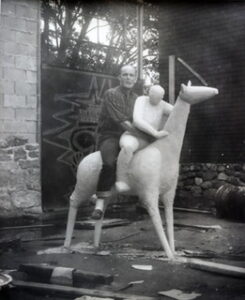

In the process of transforming the old icehouse in Westbrook, Hogfeldt also freed himself of the burden of academia as well as the competitive gallery system. He was essentially an “inside-out artist.” That is, he was neither an “insider” nor an “outsider” in the art world. He instead became an independent performer, an impresario whose vast body of works in painting and sculpture prove that he achieved his goal to “amuse and delight the eye.” In 2014, Hogfeldt passed away from Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. The structure that was the Westbrook Gallery continued to fall apart until it was razed in 2021. The new owner of the property saved and restored David Jones’ concrete sculpture of a horse and rider, which now proudly stands in front of the new building. Hogfeldt’s chapter in American art history was nearly lost forever. For the month of March 2024, an exhibition titled “Avant Colony: Unearthing the Westbrook Gallery” at the Ely Center for Contemporary Art in New Haven provided the first opportunity to view works by the artists who formed this uniquely vibrant community of artists on the Connecticut shore. This exhibition, including numerous ephemera, photographs, and news clippings, serves as enduring testament to a colony and its founder. Hogfeldt was budding artist who put his life on hold to risk it all in World War II, miraculously survived to complete his master’s degree, and then broke from the norm again to lead an intriguing group of avant painters, sculptors, performers, and musicians.

— Peter Hastings Falk

“Avant Colony: Unearthing the Westbrook Gallery”

This rediscovery exhibition runs at the Ely Center for Contemporary Art in New Haven, Connecticut during March 2024, curated by Peter Falk and Eric Litke. Included are surviving original paintings, works on paper, three-dimensional works and artist books by six artists who constituted the core active group in the gallery’s early years of 1956-64: Aage Hogfeldt [1925–2014], William Kent [1919-2012], Leo V. Jensen [1926- 2019], David T.S. Jones [1926-1996], William Skardon [1923-1983] and Robert Alan DeVoe [1928-1992].

Hogfeldt Paintings

-

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Artist’s WWII Still Life

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

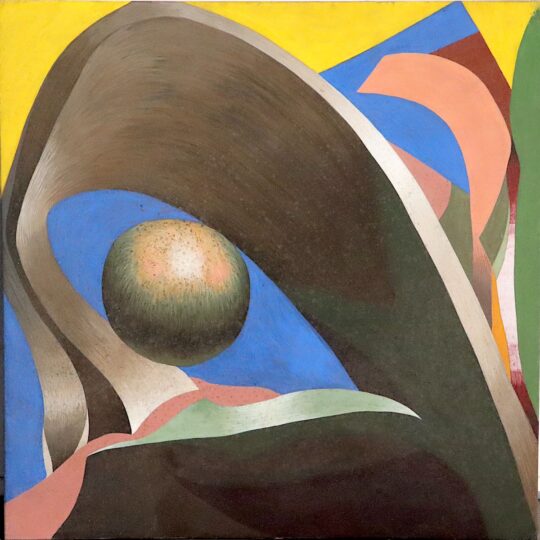

DETAILSSphere Within Curvilinear Space

24 x 24 inches (60.96 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMemories of Ocean Voyages

48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEmanating Energy

48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSChamber Orchestra

32.5 x 48.25 inches (82.55 x 122.56 cm) -

DETAILS

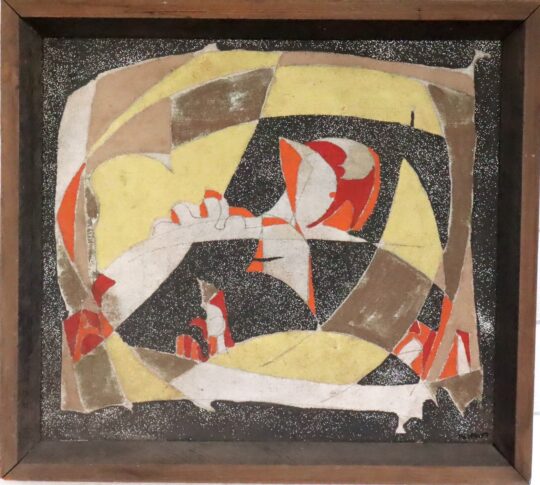

DETAILSUntitled abstraction in reds, yellows, browns, and glitter

24 x 26.5 inches (60.96 x 67.31 cm) -

DETAILS

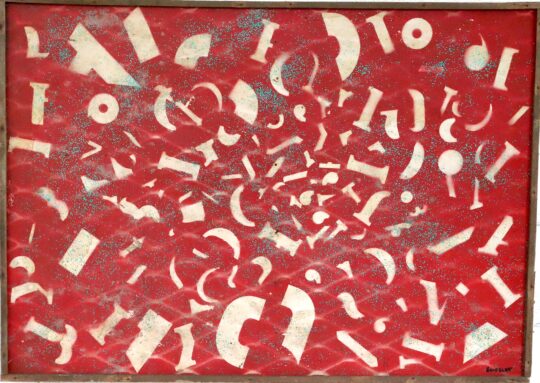

DETAILSUntitled abstraction in red spraypaint and glitter

24 x 30 inches (60.96 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

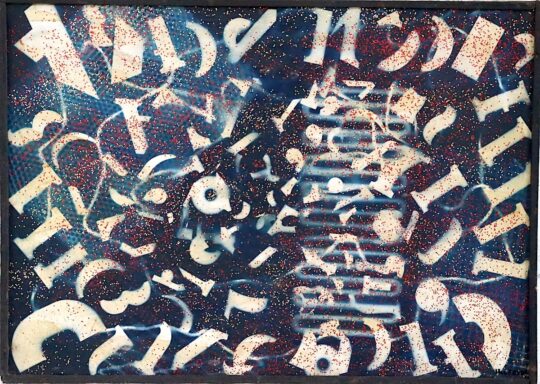

DETAILSUntitled abstraction in black and light blue spraypaint and glitter

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

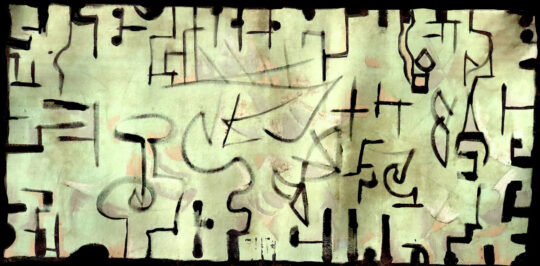

DETAILSSymphony in Spring

48 x 96 inches (121.92 x 243.84 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTabletop still life with fish

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

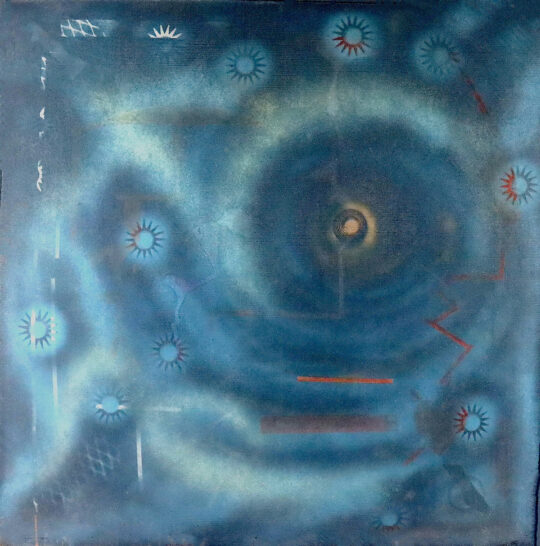

DETAILSBlue Cosmos, 1960s

48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm) -

DETAILS

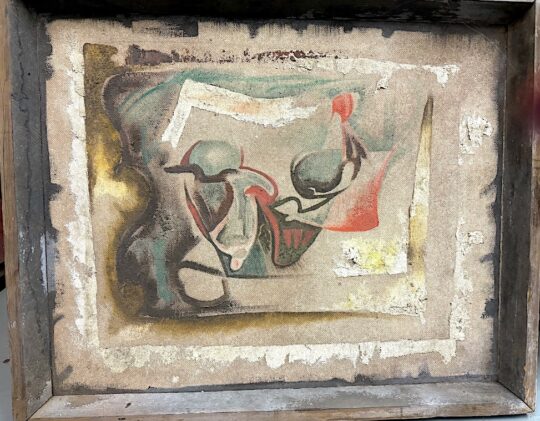

DETAILSUntitled Abstract Still Life

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm)