— by Paul Forte

Art Frees, and in doing so, it changes us.

Art is essentially formative; it develops inwardness and independence.1

— E.E. Sleinis

After a couple of hours at an exhibition we often step out into a visual world quite different

from the one we left. We see what we did not see before and see in a new way. We have learned.2

— Nelson Goodman

The freeing potential of art and how it nurtures our independence in relation to the consciousness of others is made clear by Sleinis and implied by Goodman. Sleinis further relates his critical point about the formative nature of art to the expansion of self-consciousness and intersubjectivity, i.e., the mutual recognition of an inner life. He articulates the context within which art frees us from the habitual and routine:

Awareness of oneself as a self depends on awareness of other things and other selves.

Our subjective self only fully emerges in relation to the subjectivity of others.

Art discloses the subjectivity of others and thereby promotes expanded self-consciousness 3

Goodman’s observation about experiencing a moving exhibition illustrates how our perceptions can change, and seems in sync with Sleinis’ point about the formative nature of art and how it develops inwardness and independence. The experience of art has essentially freed us from the mundane, habitual, and routine, at least, for a time. But such freedom in and of itself is not enough. Thus, Sleinis tempers his views on artistic freedom and in doing so also suggests a link to Goodman’s insights about shared cognitive development:

Art is about freedom, but it is not merely freedom from; it is also freedom to garner rewards not otherwise attainable.

Artworks that free without furnishing rewards beyond the freeing itself must surely be judged as artistic failures. 4

For Goodman, the rewards garnered through the experience of art do not merely involve learning something new, but learning in a new way. Any concern with how art might open or free our minds is thus connected to the expansion of self-consciousness, a process that is, in turn, intimately related to cognitive growth. Furthermore, Goodman and Sleinis most likely share the belief that cognitive growth of any kind involves discovery. Discovery in the arts is not only a matter of recognizing new uses of the formal and/or conceptual means of art, discovery also seems central to learning in a new way and how this has bearing on the intersubjective power of aesthetic experience. Goodman comments on the cognitive value of aesthetic understanding and I would add, its relationship to shared aesthetic experience:

For me, cognition is not limited to language or verbal thought but employs imagination, sensation,

perception, emotion, in the complex process of aesthetic understanding.5

Goodman’s insights about the extent of human cognition in the complex process of aesthetic understanding do not explicitly take up the contentious issue of intersubjectivity. While the aesthetic understanding of individuals often differs widely, the cognitive processes underlying that understanding are something that human beings share at a fundamental level. I believe that experiencing the arts can offer the most compelling evidence for the breadth of our cognitive abilities and perhaps best reveal their universal or intersubjective dimensions. I believe that Goodman is suggesting that all human beings share basic cognitive faculties, however varied in their development given an individual’s age, mental acuity, social standing, and so forth. Inferring if not recognizing these faculties and everything else that constitutes the inner life of individuals seems essential to understanding, relating to, or even empathizing with others:

Intersubjectivity is the mutual recognition of an inner life by conscious subjects. The precondition is the conscious recognition

of one’s own inner life by a subject, as well as the assumption that other subjects share the main features of the inner constitution

which the subject identifies in itself. These include language, sensation of pain, memory capability, the drive for self-preservation,

and certain interests. Intersubjectivity is used by some authors as a substitute for an objectivity, which is regarded as unachievable.6

While it is an open question as to whether or not a shared sense of objectivity (or even relatable subjectivity), is achievable, there is broad agreement on one fact of life: We all have inner lives. Intersubjectivity is a given in so far as everyone has an inner life. However, fully relating or communicating our thoughts and/or feelings to others through art or any other means is not a given, although the inferences we make about another’s expressions, however limited or even mistaken, point to another’s inner life and can initiate a process of mutual recognition or even understanding. Awareness of oneself not only depends upon an awareness of the subjectivity of others, as one’s subjective self emerges in relation to the subjectivity of others its development can be influenced by these others and vice-versa. People who are interested in the arts might be more imaginative or perceptive, at least with respect to experiencing art, than those who are not, and if they have also sharpened their critical and/or analytical abilities, they are likely to be more fully engaged cognitively. It is possible that interest in the arts might be kindled in others through art that better reveals or encourages their imaginative or perceptive capacities, and in time, perhaps their critical abilities. The point is that we all have some capacity along these lines, whether we follow the arts or not. This capacity, however developed in the individual is the basis for our intersubjectivity. To put it the other way around, it seems safe to assume that however complex aesthetic understanding is for the individual, that individual builds this understanding on the fundamentals of cognition shared by all.

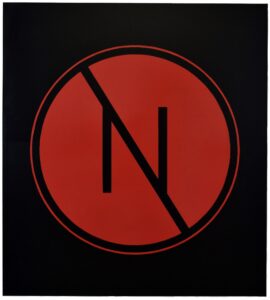

There is little doubt that the prerequisite of discovery in the arts or in any field of endeavor or even in daily life, is the freedom of an open mind. For the artist and/or thinker unconditional creative exploration and the discoveries that such exploration might lead to depend upon the cultivation of inner vision. A major problem facing the arts today is how to connect the inner vision of artists outside the purview of audiences often hungry for creative discovery. This problem is largely a socio-political and/or economic matter and the short-sightedness that accompanies the decisions of curators and others is contributing to the cultural malaise. But I do not wish to belabor this point. I will simply say that it seems imperative that freedom also be extended to the audience for art: Unconditional access to potentially rewarding art, specifically in terms of exhibition opportunities for independent artists exploring the intersubjective potential of art. It seems that the art that is often overlooked or out of favor today is work that clearly reveals the development of inwardness and independence and how this might resonate with others. How is the formative nature of art and its development of inwardness and independence related to a deeper understanding of cognition and its role in intersubjective experience and understanding? Any deeper understanding of cognition must also be accompanied by a broader understanding of this fundamentally human ability. Our individual cognitive abilities are colored by our unique experiences and yet we share core cognitive abilities with others. Our differences in terms of gender, race, and so forth, contribute to the inwardness and independence we are able to achieve as individuals, and yet however unique we might be in this regard, our achievements are always based on shared cognitive faculties seemingly unique to our species.

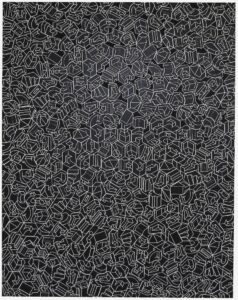

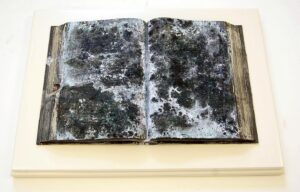

Today’s art market seems largely uninterested in the potential of art to enhance cognition and expand consciousness. It has no emphasis on the need to fully realize the intersubjective power of art. Formal and/or conceptual innovations in the arts may no longer be possible, leaving artistic discovery in terms of new idioms to contribute to the enhancement of our cognitive abilities, thereby expanding consciousness. Innovative works in distinctive individual styles that are provocative and cognitively engaging, are central to the freeing potential of art. This realization is at the core of a new avantgarde that has the potential to unsettle the complacency of art world insiders and their conformity to the status quo, which might explain much of the resistance to art that is both cognitively engaging and out of step with the prevailing consensus. The supporters of this revitalized art practice are often united in their belief that such art often doesn’t conform to current socio-political and/or aesthetic expectations held primarily by artists and others with vested interests in the status quo. Moreover, cognitively engaging art realized through fresh idioms is often revolutionary in its potential to deliver more than momentary diversions for a great many people, creating deeper subjective connections and mutual understanding. This is essentially the promise of creative art. The crux of the matter involves embodying creative thought and feeling in the art making process, which necessarily requires the artist and the audience paying attention to the formal dimensions and material of the artwork, with the understanding that such things are necessary but not sufficient when making or viewing a work of art. The artist thinks and feels imaginatively with images, objects, and materials, a subjective interaction that when successful elicits similar interactions in the audience. When properly recognized and understood, revolutionary or radical aesthetic practice can initiate a reevaluation in terms of art making, criticism, collecting, and curating — thus leading to a significant shift in our understanding of the place of art in our lives. Philosopher Nelson Goodman was one of the first to call for a reevaluation of the arts in relation to cognition. Goodman, writing almost forty years ago again put the issue succinctly:

The myths of the innocent eye, the insular intellect, the mindless emotion, are obsolete.

Sensation and perception and feeling and reason are all facets of cognition, and they affect and are affected by each other.

Works work when they inform vision; inform not by supplying information but by forming or re-forming or transforming vision;

vision not as confined to ocular perception but as understanding in general. 7

I believe that a new approach to art making based on this understanding and practice is well underway. Goodman’s view on how artworks work, particularly stressing that they inform not by supplying information but by reforming or transforming vision can be seen as a needed corrective addressed to conceptual art practices in the early 1970s, around the time that Goodman was writing this. Goodman was, however, primarily concerned with how we understand the various works of science and the collections in museums of, for example, cultural and natural history. He argued that the differences between the arts and sciences were misunderstood and exaggerated, that there are points of convergence in our experience and understanding of science and art. Many conceptual artists probably shared Goodman’s viewpoint, which lent credence to their work. As important as Goodman’s viewpoint about art and science is, my purpose here is to recognize the groundbreaking nature of conceptual art, that it initiated new attitudes toward art making, and to suggest a critical reason that it eventually evolved, particularly with regard to Sleinis’ view about art’s freedom to garner rewards. And yet, many in the art world have either forgotten or are unaware of Sleinis’ and Goodman’s critical insights. The insight that art offers ways of understanding the world as important as science, is founded on its intersubjective power. And it is this power that promises to free us from our isolation, connecting us with others made newly independent through shared inwardness.

In light of all this one must ask: Where are the champions of artists who realize through their art and/or writing the deep insights of thinkers like Nelson Goodman and E.E. Sleinis? In 2006 I raised a number of provocative questions that bear on the freedom of art and artists that remain relevant:

Where are the advocates of the arts who might stand behind those artists who, with no support from the art market,

continue year after year to produce art that is elegant, thoughtful, and compelling? Where are the true guardians of culture?

Where are the people who are willing and able and more than happy to lift the curtain on such art? Just where are they?

I am convinced that there is a great deal at stake here. Careers of individual artists, no matter how accomplished, are

not really the issue. Of course, and this is an opinion shared by many who really care about art, the vitality of the art world

depends upon new blood (and not just new faces), but even this pales in terms of a deeper, systemic problem.

What is ultimately at stake is nothing less than the freedom of our culture, our society. Artists who are truly independent,

artists who value art first and foremost as an expression of their uniqueness, may be the truest and boldest defenders

of something essential to our democracy. All artists who cherish freedom in America are behind the lines today.

We need the support of those on the inside who are our creative counterparts. We need people of courage and vision

who will act on their convictions.8

Many of us are still waiting for answers to these questions.

Footnotes

- E.E. Sleinis, Art and Freedom, University of Illinois Press, 2003. 6.

- Nelson Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, Harvard University Press, 1984. 85.

- E.E. Sleinis, Art and Freedom, 13.

- E.E. Sleinis, Art and Freedom, 195.

- Nelson Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, 9.

- Online Dictionary of Arguments, Philosophy Lexicon,

- Nelson Goodman, Of Mind and Other Matters, 180.

- Paul Forte, unpublished essay, 2006.