The Wizard of Brooklyn

“I had a dream of a turbulent ocean

with shark fins coming through my floor,cutting me up.”

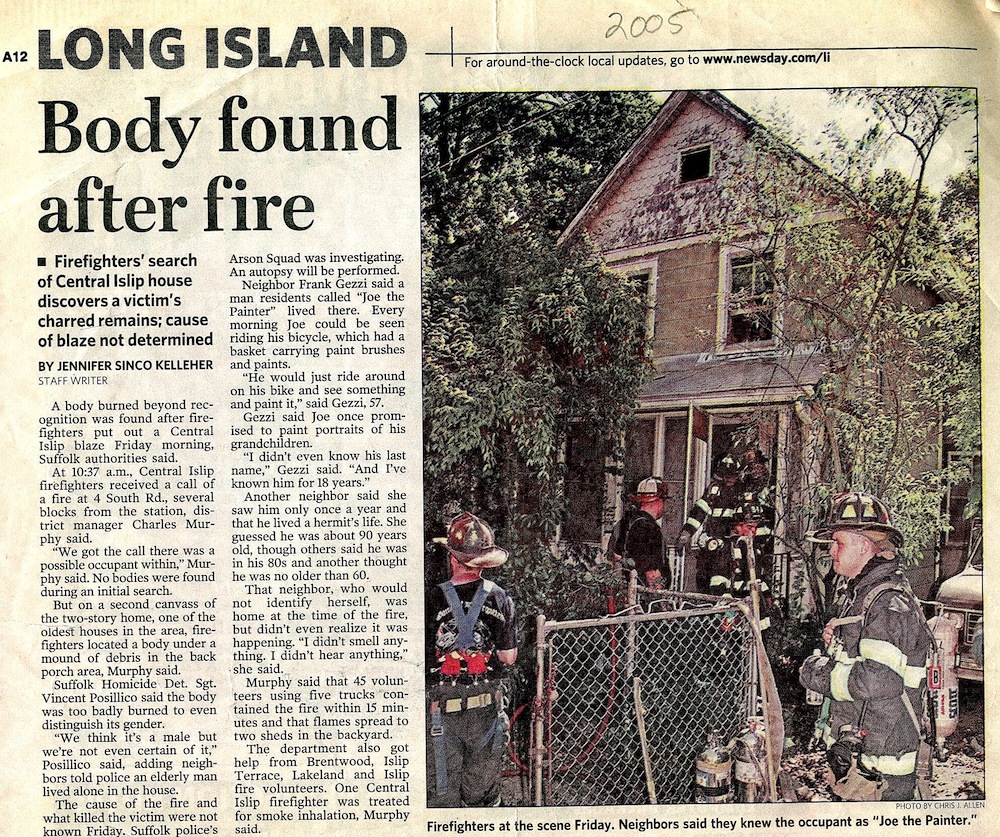

On the morning of September 30th, 2005, the fire that had quickly devoured the back porch at 4 South Road in Central Islip had just begun to push its way into the ground floor. Fortunately, the firehouse was just a few blocks away and the quick response of forty-five volunteer firemen prevented the conflagration from consuming the entire house. Climbing over the collapsed porch they pushed through the back door, and began to douse the home. The interior could best be described as a path. That is, upon entering the house, the firemen were immediately channeled to a narrow path — created by stacks of books, magazines, and papers — that wound its way from room to room. Together these stacks, which had just begun to catch fire, formed walls towering up to the ceilings on both sides of the path. To their surprise the firemen discovered the bedrooms upstairs held stacks of paintings — thousands of them — but these works had escaped largely unscathed. Apparently, no one was at home.

But back outside, as the team searched through the mound of rubble and embers they eventually discovered a body that had become charred beyond recognition. It took three days before the forensic pathologist could determine that the remains were those of Joseph Bartnikowski. The arson squad traced the fire’s origin to an electric space heater. The artist was was just a few days short of his seventy-ninth birthday. A heart attack seemed unlikely because, ironically, the artist who stood out with a flowing white mane and beard was an incredibly fit apostle of health and wellness. Had he tripped, fallen to the floor, and become knocked out as he hit his head? Did he suffer a cerebral aneurism as had his father? Or was he murdered? The homicide detective could only conclude that the cause of death was unknown. The tragedy would remain an unsolved mystery.

Parked in the driveway beside the house was the artist’s old Ford van. Its white coat had surrendered gradually over the years to a stained and mottled yellow patina imparted by rusting. This van and the porch are the two places where the artist slept — not in his four-bedroom house — because he felt the outdoors was a healthier alternative. Besides, his house had become too jammed with stacks of papers and paintings.

Joe Bartnikowski was something of a mystery in the neighborhood. No one knew his last name. They simply referred to him as “Joe the Painter,” that lone eccentric who left early in the morning on his old green bicycle. The wire basket mounted in front of the handlebars was packed with art supplies. Strapped to the rack above the rear fender was a flat stack of artist boards and canvas wrapped in plastic garbage bags and secured with bungee cords. No one knew that for more than thirty years his destination was just a mile away at the Central Islip Psychiatric Center where he worked as an attendant. Devoted to improving the mental and physical wellness of the patients, he kept exhaustive notes about the effectiveness of his own experiences with art therapies as well as his teaching various musical instruments to patients.

When Bartnikowski was not working at the psychiatric hospital or painting on its grounds he was still doggedly on his artistic mission, driving his van on painting sojourns. He frequently returned to paint street scenes and portraits at favorite Brooklyn locations, especially his native Greenpoint and the Williamsburg neighborhood just to its south. Or he would drive east out to the Hamptons to paint beach scenes. And in the winters it had become his migratory pattern to drive south to Fredericksburg, Virginia, with his green bicycle strapped inside the van. From there he often ventured hundreds of miles farther into the Deep South. He finally found Morven, North Carolina, a tiny and largely African-American village near the border of South Carolina. In the summer of 1985, just a few miles up the road from Morven, Steven Spielberg filmed the movie, “The Color Purple.” Bartnikowski bought twenty-six acres in Morven but he never built upon them. He just liked to visit in his van.

Emergence of the Artist

Late in life Joseph Bartnikowski would reflect that his birth in Brooklyn in 1926 was an event where he came “spinning out of nothingness, scattering stars like dust. This is the mechanics of creation.” When his mother was pregnant his father died suddenly, possibly of a cerebral aneurism. The young widow raised four children on Diamond Street in the Greenpoint section, close to Manhattan Avenue in the neighborhood known as Little Poland. Joseph’s older brother, Adam, who was mentally instable, compounded her hardship.

Among Joseph’s earliest memories were drawing in color chalks on the streets. The children attended the St. Stanislaus Kostka School near Oakland Street. “As a boy the greatest delight was being alone in empty rooms on Oakland Street. The silence — hollow sounds of my own footsteps and the observation of distant rooms and windows with all its colors of over-painted closets.”

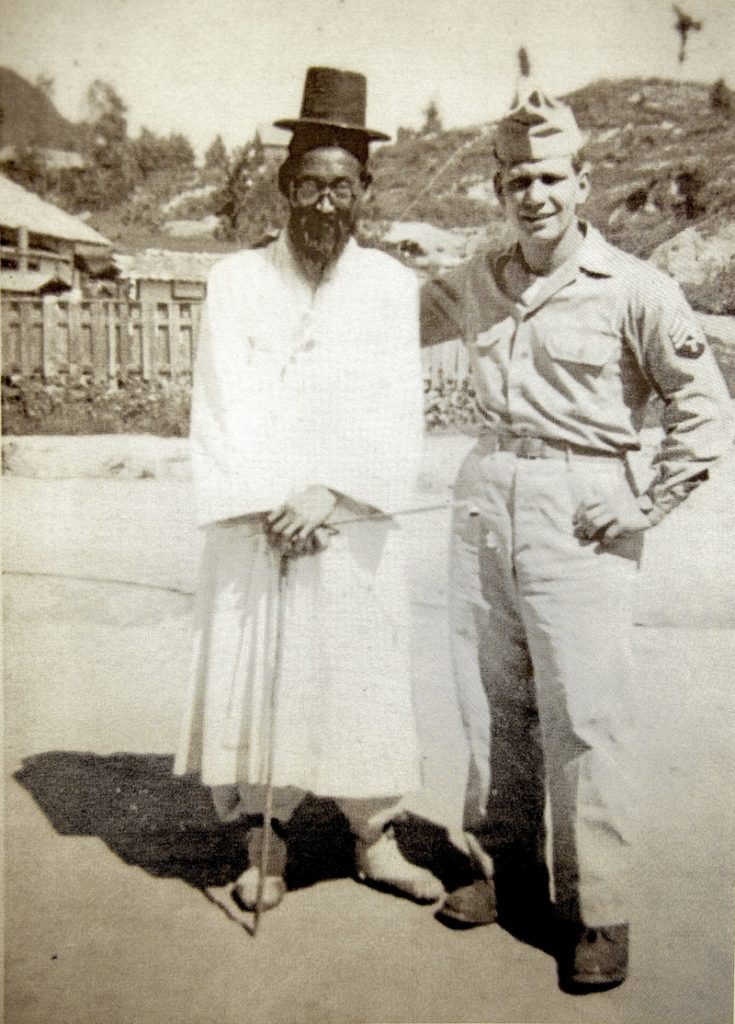

The boy was fascinated by musical instruments, too, learning first how to play the piano, then the violin, and finally the trumpet. He was the only person in his family to graduate from high school. His graduation in 1945 coincided with the end of Word War II but the nineteen-year-old was nevertheless drafted into the Army. He joined the more than 350,000 soldiers stationed throughout Occupied Japan under General Douglas MacArthur’s Eight Army. He played the trumpet in the military band and served as a “Tec 4,” doing maintenance and repairs on vehicles and aircraft. After about a year large numbers of replacement troops began to arrive in the country and Bartnikowski could return to Brooklyn where he lived with his mother, sister, and an increasingly troubled brother.

Soon a young trumpet player called “Bart” emerged leading his own sixteen-piece jazz band performing around the city. He never wrote about how or why he transitioned to becoming an artist but after a few years he quit the band and by the early 1950s was on his way to becoming a self-taught master in painting. At the same time his brother Adam’s plight was growing. While relatives remained unclear about his diagnosis it was suggested that such deep depression — perhaps even paranoid schizophrenia — would best be treated by committing him to the Pilgrim State Hospital in Brentwood, Long Island. Pilgrim was the world’s largest mental hospital. In 1938 a haunting photo-essay on Pilgrim’s patients in straightjackets appeared in Life magazine, shot by the great photojournalist Alfred Eisenstaedt. There were no anti-psychotic drugs during the period, and soon after World War II Pilgrim became a leader in more aggressive treatments, such as electro-convulsive therapy and lobotomy. Often referred to as the “ice pick” technique, a hand drill was used to penetrate both sides of the skull. The surgeon then probed with metal rods to shock the frontal lobe. The rate of irreversable damage was high. Allen Ginsberg, one of the “Beat Generation” writers, visited his mother in mental hospitals for fifteen years. She underwent a lobotomy at Pilgrim and died there in 1956. Traumatized by her death, Ginsberg wrote poetry about her psychiatric problems for the rest of his life. In 1992 ABC’s prime time news program, 20/20, reported on the history of lobotomies performed at Pilgrim.

In 1959 officials at Pilgrim notified the Bartnikowskis that Adam had suddenly died. The reason for his death was unclear but was likely owing to the same treatment. After all, most of the patients at Pilgrim suffered from paranoid schizophrenia. Lamenting the loss of a brother who was only about thirty-eight, Joseph became deeply introspective and left his mother’s home in Brooklyn. Only such grief could have been the catalyst for his taking up the position of an attendant in residence at the Central Islip Psychiatric Center just a few miles away from Pilgrim. Living at the hospital for more than thirty years he developed an enduring commitment to the patients. Was Joseph trying to save others from the conditions under which Adam was committed and died? Over the years Joseph did witness the introduction of new anti-psychotic drugs and the changes in laws governing the commitment of patients but his personal beliefs for treatment remained firmly rooted in spiritualism and holistic medicine.

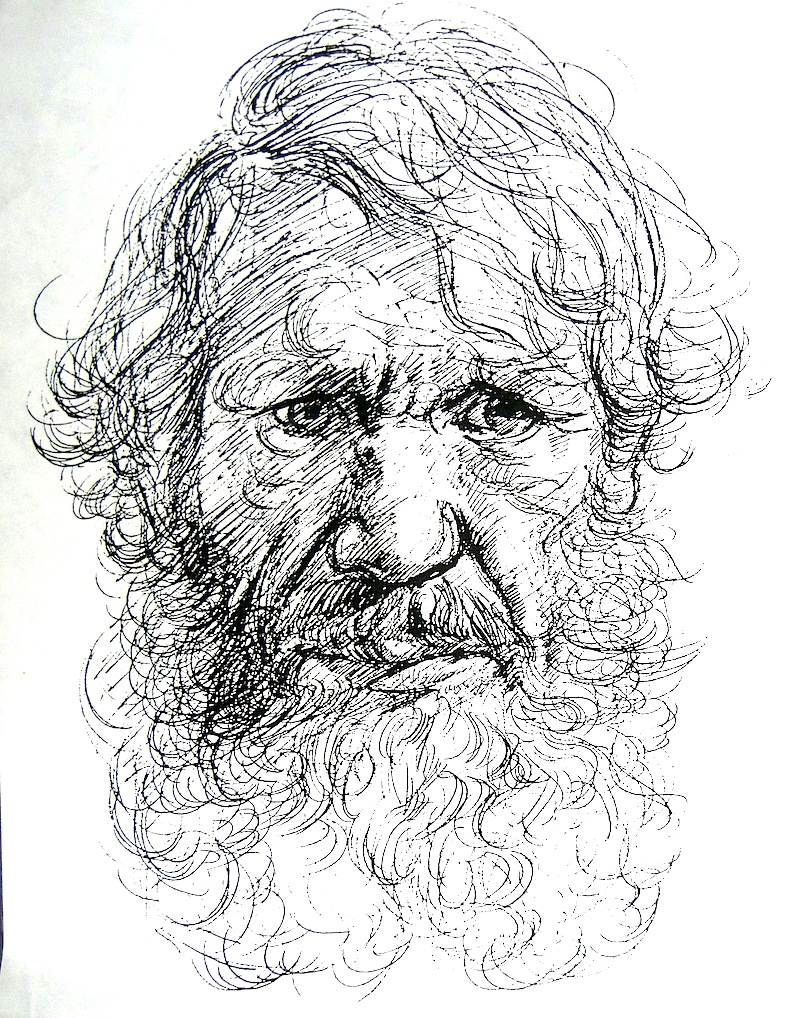

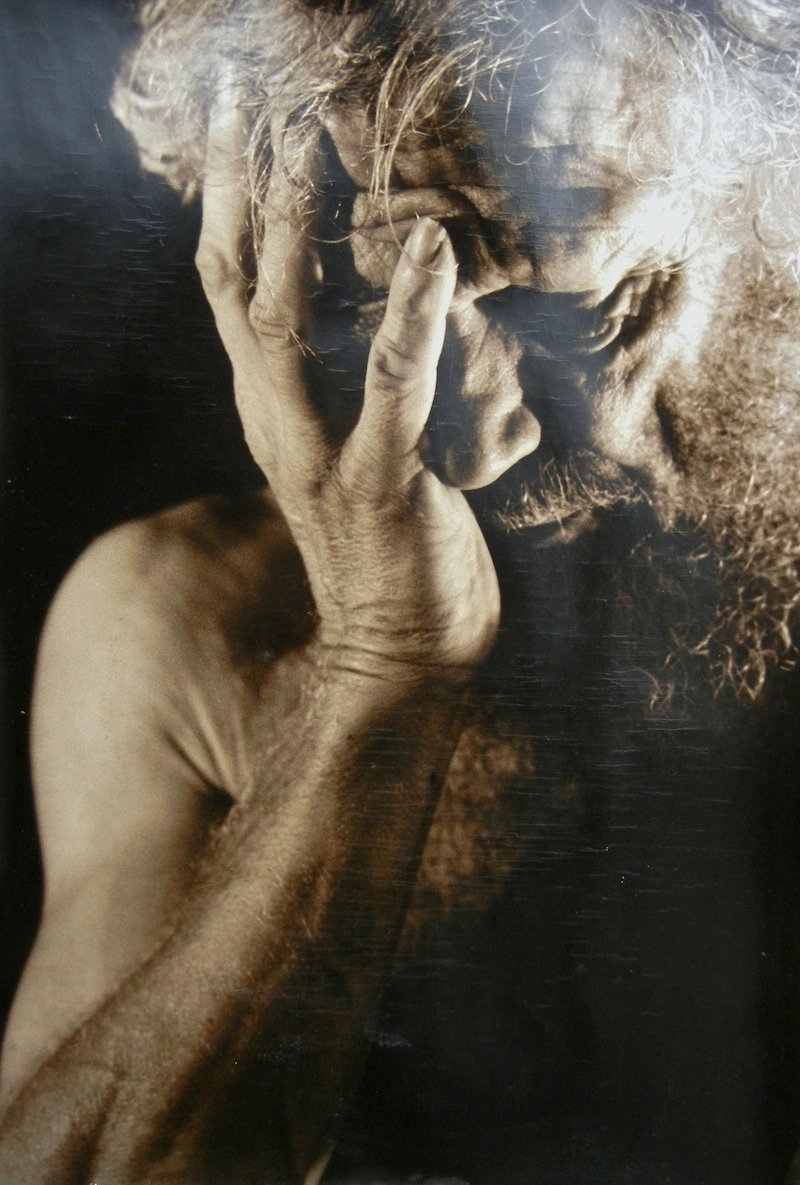

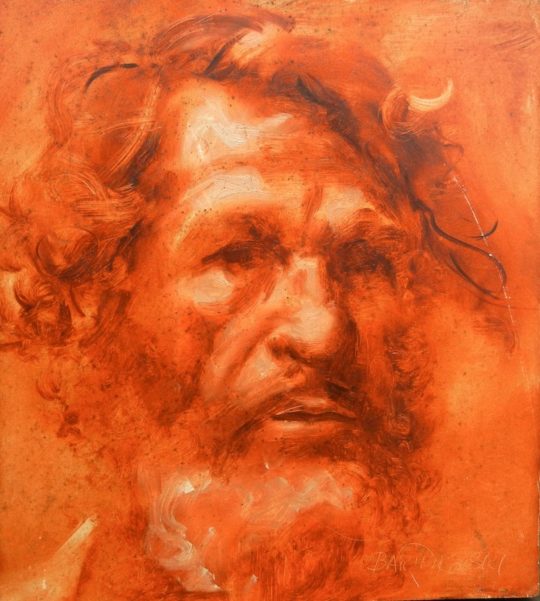

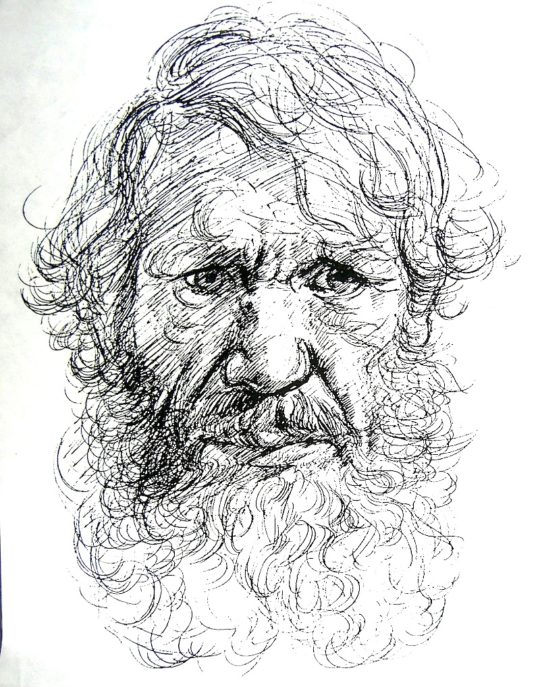

Despite having his own room at the hospital, living amidst the inmates often proved stressful. Numerous paintings show that he spent a great amount of time painting outdoors scenes around the campus. And during warm weather he always preferred to sleep outside on the grass, avoiding the frequently disruptive cacophonies of the inmates indoors. Nevertheless, his immersion in the challenge of his job at the hospital was wholehearted and seemed to reinforce his intense focus on transforming himself into a master of painting. Despite the rescue of numerous boxes overflowing with papers, letters, and manuscripts the answers to many questions surrounding his change remain elusive. Since the early 1950s his primary classrooms had been the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Art Museum. So obsessed was he in achieving his goal of mastery that he claimed to have deprived himself of women and alcohol for the full decade of the 1960s. When he was not at the psychiatric hospital he was haunting the museums. At first he focused upon the Old Masters and always brought a magnifying glass to study their brushstrokes and techniques. Back at his room he focused upon himself as his primary model, painting hundreds of self-portraits. Anyone who has attempted self-portraiture knows that hours of being face-to-face with one’s reflection demand the inherently difficult task of introspection. He became proficient in Rembrandt’s technique and signature dramatic lighting. Soon his portraits appeared to have come from the easel of one who was academically trained in the academies of nineteenth century Paris or Munich, or today’s ateliers of classical realism in Florence. His portraits certainly provide no clues that he was completely self-taught — but he fits the art market’s definition of an outsider artist.

Bartnikowski’s mission became so all-consuming that he would only visit his mother and sister every five years or so. Such surprise visits would last about an hour just to make sure they were well. He would then leave just as quickly, never having spoken about his work at the hospital or his art. Having spent the 1960s in museums, by the early 1970s he felt confident about painting outside. Instead of gazing into a mirror he now had urban vistas before him, the city’s clamor, and an endless array of fascinating characters. Immediately his Old Master palette of burnt umbers and ochres would give way to a newfound joy in light and color. And palette knives were added to the bundle of brushes in his satchel. After his mother died in 1972 his brief visits to his sister occurred at intervals even greater than five years. It was as if his mission required that he break all ties with his past. No phone calls to any members of his family. No letters. Not even holiday cards. Even his neighbors who labeled him a recluse would never know that willful isolation and retraction from society were never his intent. They would never understand that he was transforming into the Wizard.

Emergence of the Wizard

Wizards see themselves as citizens of the cosmos…The Wizard has a peculiar relationship with his body. He sees it as a wisp of consciousness taking shape in the world — much as rocks, trees, mountains, words, wishes, and dreams flow and take shape. The fact that a word or a dream is insubstantial while one’s body is solid does not disturb the Wizard. Wizards lack our ordinary prejudices that equate solid with real. A Wizard does not see himself dreaming of a larger world. A Wizard is a world dreaming of local events.

— July 3, 1996, from “The Way of the Wizard,” a chapter among

Bartnikowski’s manuscripts for an unpublished book.

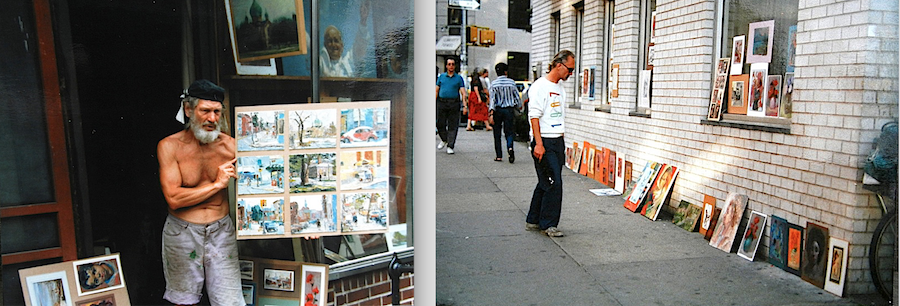

Over the course thirty-five years Bartnikowski could frequently be found at his easel painting on street corners. He stood lean and weathered. His blue eyes were even more piercing because he had the tanned and deeply creased skin of a mariner, his face framed by wild shocks of long white hair. Leaning nearby would be his bicycle, loaded with art supplies. The street environment became so significant to him that throughout the 1980s he rented a ground floor studio in Williamsburg at 122 Bedford Avenue. When he wandered about Brooklyn on frigid days he would find comfort — and subjects to paint — in laundromats where he could stay warm and loosen his palette of cold oils on the radiator. To his thousands of casual observers over the years, “Bart” indeed seemed to be an entertaining performer, deftly capturing the likenesses of those who would sit for him. Enhancing the mystery was the fact that this street artist was no peddler. Rarely would he sell to his sitters their own portrait or accommodate a collector who admired a street scene. At least 3,000 of his portraits were of children but none of them were commissioned. He simply loved to capture their spontaneous and refreshingly honest facial gestures. He typically priced the great majority of his paintings beyond the reach of the public. Instead, he simply cared most about the gathering together of a large body of work and hoping that some day it would be appreciated. In 1985 he bought an old house in Central Islip in a neighborhood near the mental hospital and it became the ideal repository of his paintings, papers, and other accumulations.

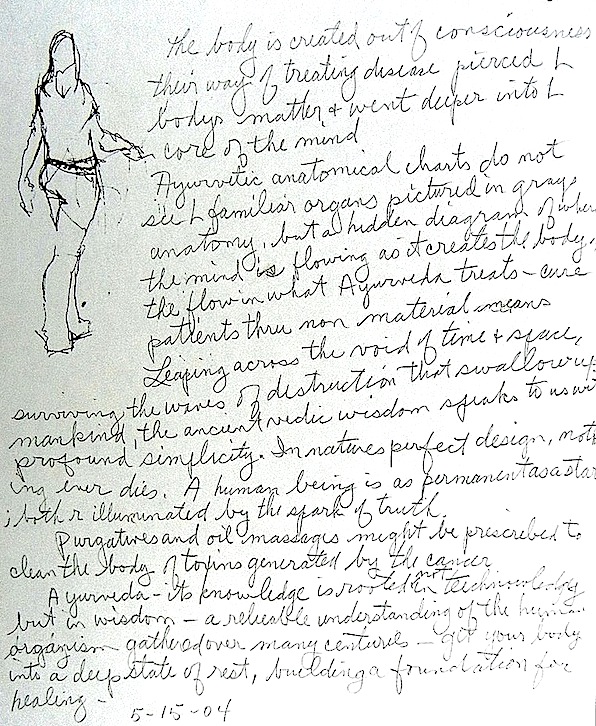

When a street artist’s paintings are viewed on the sidewalks instead of under the spotlights of the white cube environment of an established art gallery they may be easily dismissed as whimsical. But Bartnikowski never pursued the financial reward or the social bootstrapping that the Manhattan galleries could have provided. Instead, the Wizard of Brooklyn consistently lived as “a world dreaming of local events” — one of many quotes found in the stacks of hand-written papers that clearly describe a life immersed in art. He even developed a unique form of writing — his own variation of shorthand — creating symbols that are variants of letters standing for certain words. Reading the manuscripts is therefore difficult without first deciphering the full range of his symbols. For example, a V with the right leg flaring to the right meant “that”; and, a backwards L (looking like a reverse check-mark) meant “the.”

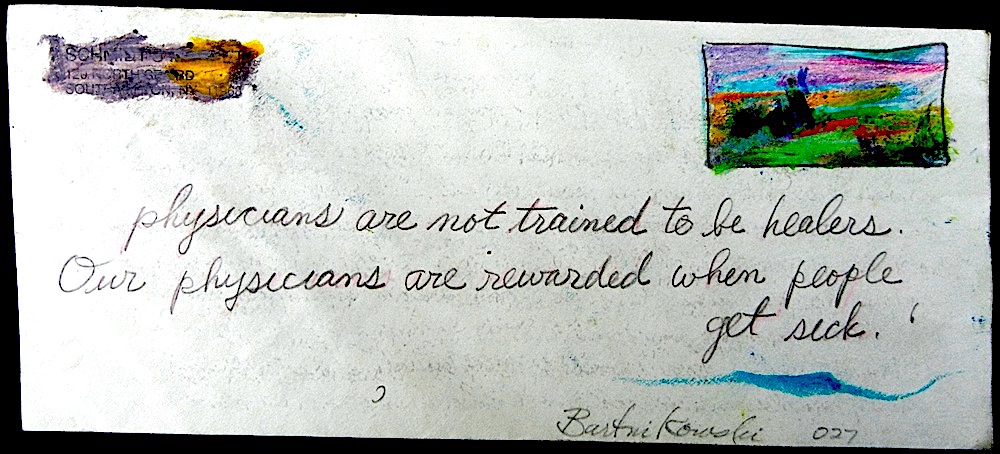

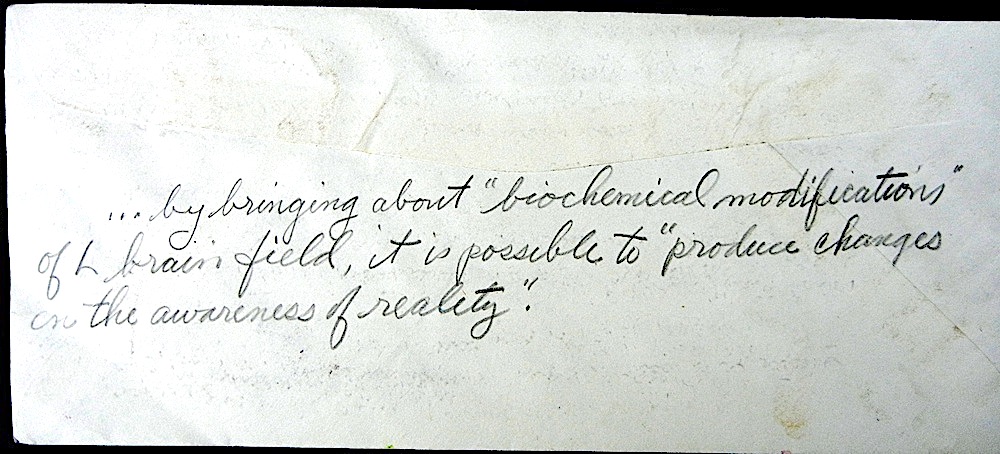

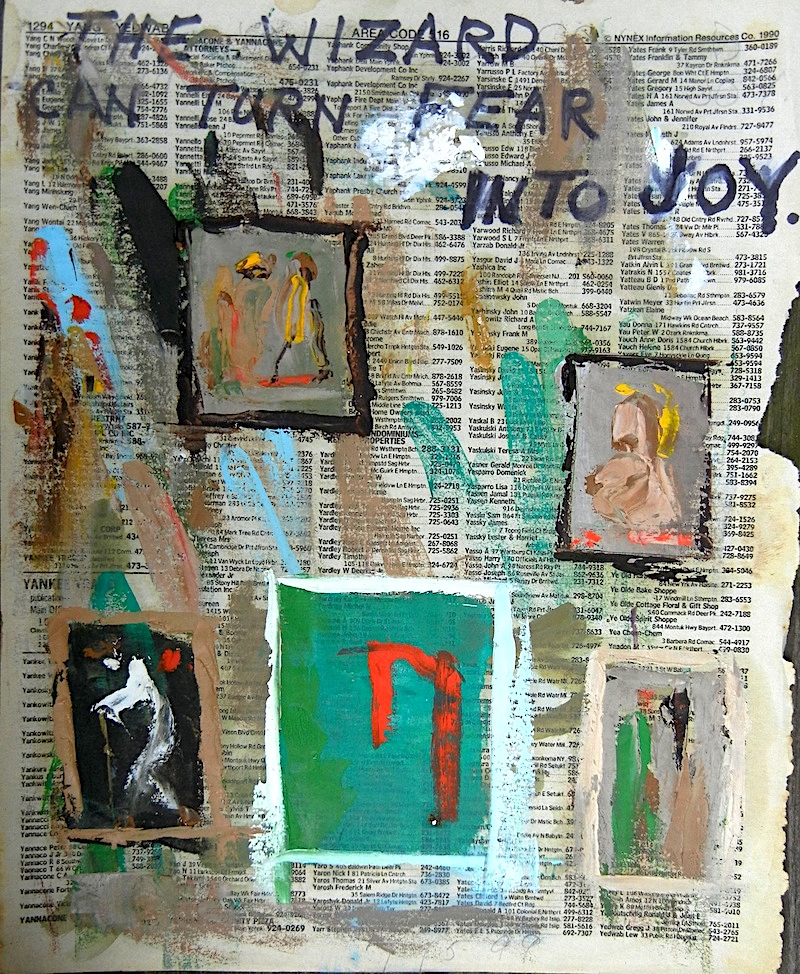

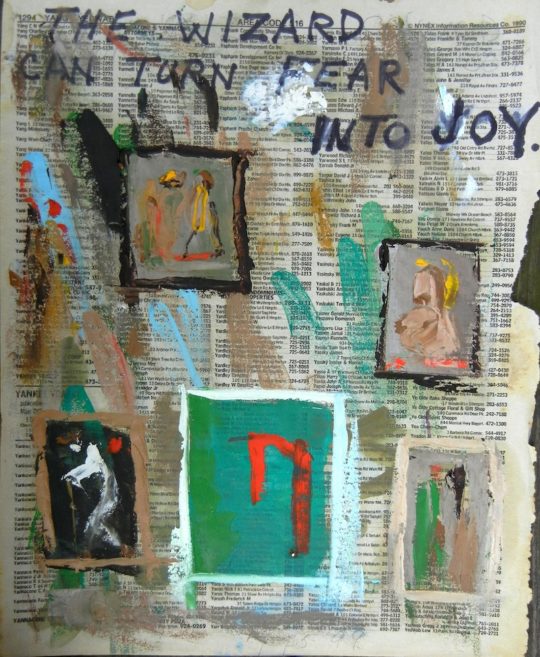

His writings were voluminous, revealing a deep conviction that we should strive to reinforce what he saw as the vibrant integration of our mental, physical, and spiritual lives. Notebooks were filled with repetitive and unrelenting directives for holistic treatments, philosophy, mysticism, and art. These notes were frequently interwoven in the white spaces of drawings — and even spilled into a series painted on telephone book pages. As the years passed he wrote hundreds of numbered pages building towards a book. The chapter called “The Wizard” was joined by other thematic chapters such as “Waking Dreamer,” “Your Body as it Really Is,” and “Metabolism and Self-Referral.” He always wrote on found paper. Favorites included a supply of discarded order sheets from Kathleen’s Bake Shop in Southampton (renamed Tate’s Bake Shop), photocopies from the Brentwood Public Library, and flyers from businesses such as SoHo Art Materials and Farmville Mini-Storage. Letter envelopes, often bearing a figure or design, were favorites for short philosophical statements, often accompanied by sketches.

The majority of Bartnikowski’s writings focused on how a “new mind awareness” could influence a “new body awareness,” thereby promoting healing and allowing the patient to tolerate higher levels of stress. When he wrote that “All diseases are the result of the destruction of the flow of intelligence” he was not referring to intellectual capacity but “to the cellular and even sub-cellular levels where enzymes, genes, receptors, antibodies, hormones, and neurons are expressions of intelligence.” Even his writings on art are tied to this cross-disciplinary approach, and are found interspersed among pages dedicated to wellness through psychology, philosophy, and alternative medicine. He felt a deep compassion for the patients at the psychiatric hospital where he worked, noting that their mental problems were almost always accompanied by degenerative diseases. Because he recognized these two problems as reinforcing each other in a downward spiral he became a fierce advocate of alternatives to drugs and surgery.

He also introduced the patients to Tai Chi. “Our health is our only real material wealth. Often, however, the value of health is only realized when it is too late. For mental patients Tai Chi provides the scattered or erratic mental energies of the patient with his own body as a focusing point. This concentrated exercise helps the patient’s mind — a new body awareness to re-learn a basic trust in our bodies. That trust is reflected in an incredible ability to tolerate higher levels of stress without having to activate emotional and physical armoring systems.”

Convinced that human creative powers could induce the body’s self-healing mechanisms, or “biological cognition,” he also studied the origins of color therapy and the psycho-neuro effects it promised. His extensive notes show that he studied Dr. Edwin D. Babbitt’s Principles of Light and Color (1878), which was the first to espouse chromatotherapy (healing with colored lights) as a treatment for many ailments. Dr. Walter J. Kilner’s The Human Atmosphere (1911) described his screening technique for viewing the aura emitted by the human body and he applied this to medical diagnoses. In 1920 Dr. Dinshah P. Ghadiali introduced a series of healing lamps using colored filters. In 1947 Dr. Max Lüscher introduced a form of color therapy to determine a patient’s psychological state. Many of these pioneering efforts have been debunked by the medical profession as pseudoscience; nevertheless, Bartnikowski continued to research more contemporary work in color therapy such as Theo Gimble’s Hygeia College for Color/Light Therapy in England, which during the 1990s was turning out “Holistic Color Consultants.” He also became a subscribing member of the mail-order library of Rudolph Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society in America and its School for Spiritual Science because among its many offerings were treatises on the significance of color in artistic expression.

But it was Faber Birren [1900-1988] — by the 1950s widely recognized as the leading authority in the field — who exerted the greatest influence upon him. Birren’s books, such as Color and Human Response, sparked Bartnikowski to apply his color therapies to the mental patients. He found confirmation that reds encouraged vitality and fought depression. Oranges aided digestion while inducing intelligent action. Yellows calmed the nervous system while sparking creativity. Greens eased emotional disorders and made one more empathic. Blues helped prevent irritability and brought serenity. Indigo aided the eyes, ears, and nose while making one more intuitive and spiritual. Bartnikowski then developed his own art therapy, especially drawing upon his careful studies of the palettes and styles of Velasquez and Van Gogh. He noted not only how their mixed colors but their brushwork created certain effects that, in turn, could elicit psychic and physical wellness. He wrote, “You cannot help the body without helping the eyes and visual senses.”

The doctors gave him free reign to pursue “treating” their patients with both color therapy and music — likely because they saw it as innocuous or even amusing. Going deeper, when he wrote that he was convinced that the human body is “an infinite intelligence operation” he was referring not to a capacity for smartness but to the intricate coordination of the firing of every cell of every organ. This is why he saw painting as not only the creation of tangible images and colors but as a product inseparable from the expression of emotion. He saw this pairing as “two major ways to change our minds and bodies to communicate with each other” in order to bring about greater health and well-being. He felt that one’s brain chemistry could be altered to induce creative acts and spiritual enlightenment. In a sequence of thought-action steps, sub-atomic particles are triggered, affecting atoms, affecting molecules, affecting cells, and affecting organs. Eventually, a pattern encouraging a new “cellular awareness” would cause the body to adopt a healthy metabolism and psychological wellness that would become perpetuated as self-referential.

Ultimately, Bartnikowski’s manuscripts on philosophy and spiritualism affirmed the validity for his hoarding of thousands of paintings as testament to his belief that they would some day play important roles in people’s lives because they emitted a spiritual energy.

The Wizard’s Spiritual Quest

“The world is my cosmic body and the space between my skin is my personal body — and the two are essentially part of the same continuum. The cosmic mind is just a simple way of saying a non-local field of information with self-referral feedback loops of a cybernetic nature.”

Bartnikowski never specified the turning point in the 1950s when his desire was sparked to become an artist. But after years in metamorphosis he emerged as both an artist and “The Wizard.” As he sought sources to explain the extraordinary acuity that came with his transformation he came to understand that his art-making was a divine science. In the 1960s adherents to the New Age lifestyle often blended mysticism, philosophy, theosophy, and even quantum physics as doctrines essential to understanding the seamless flow between the macrocosm and the microcosm. Bartnikowski saw no disparity, no divide, between painting, mental health, astrophysics, and physical well-being. Thus, in his writing he adopted the personification of The Wizard, frequently identifying with Merlin, and armed with the ability to break from the time-bound world. “Our concept of a linear path from birth to death is the spell of mortality,” he wrote.

Bartnikowski was a voracious reader, citing a wide range of philosophers and scientists, from Zukov’s The Dancing Wu Li Masters to Stovertka’s The World of Atoms and Quarks and Capra’s The Tao of Physics. In his quest to master mind-body awareness he concluded that subatomic particles defy rational understanding and that they instantly react to decisions made elsewhere in the body — even elsewhere in the universe. “To me, this simply is the scientific world beginning to catch up with all that the spiritual masters have been relating for centuries,” he wrote. He especially lauded Einstein for his “Theory of Relativity,” for having overcome the mental barrier of linear time, citing the genius’s feelings of “rapturous amazement of the harmony of natural laws.”

Bartnikowski frequently attended guest lectures by academics at the nearby community centers, particularly tuning in to the New Age speakers. The movement’s historical roots dated to the late nineteenth century when the spiritualist Helena Petrovna Blavatsky became the founder of The Theosophical Society. She published The Secret Doctrine in 1888, and her book’s subtitle — “the synthesis of science, religion, and philosophy” — succinctly captures Bartnikowski’s beliefs. In the mid twentieth century the most widely read proponent of Blavatsky’s theosophy was Walter Russell [1871–1963], author of The Message of the Divine Iliad. An artist most of his life, at age fifty Russell had an epiphany that lasted thirty-nine days, turning him into a mystic. After his death in 1963 his teachings were continued and the term “New Age” was coined and entered American counterculture, assisted largely by the hippie movement. Many subscribed to Russell’s A Home Study Course in Cosmic Consciousness wherein he described his epiphany as “that rarest of all spiritual phenomena known as the Illumination into the Light of Cosmic Consciousness.” Inseparable from that cosmic consciousness was a moral imperative:

“This New Age is marking the dawn of a new world-thought. That new thought is a new cosmic concept of the value of man to man. The whole world is discovering that all mankind is one and that the unity of man is real – not just an abstract idea. Mankind is beginning to discover that the hurt of any man hurts every man, and, conversely, the uplift of any man uplifts every man” [Theosophy, Vol. 48, No. 10, Aug. 1960].

Bartnikowski found this tenet compelling because every day at the psychiatric hospital he felt “the hurt of every man” — and painful reminders of his own brother. “God calls you to the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet,” he wrote. “If you don’t go, you don’t see.” Theosophists also regarded an intimate knowledge of the effects of the body’s magnetism and electricity as a necessary component of understanding man. Indeed, Bartnikowski was well aware of an extreme where shock treatments at the hospital could sometimes render a mind virtually inert.

It is interesting to note Blavatsky’s profound impact on several generations of artists, as described in The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890-1985, published in 1986 by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A seminal and comprehensive reference work, its eponymous ground-breaking exhibition featured ninety-five artists. Mondrian [1872-1944], was among the many artists immersed in Blavatsky’s theosophy. After 1908, his life and art was inspired by a search for spiritual knowledge. Edvard Munch [1863-1944], who was interested in spiritualism and had strong leanings to the occult, was committed to a psychiatric clinic for eight months. His contemporary, Kandinsky [1866-1944] espoused Blavatsky’s theosophy, and believed that the artist could create “cosmic transformations.” In turn, Marsden Hartley [1877-1943] was influenced directly by Kandinsky’s beliefs and became immersed in mystical symbolism, the occult, and the study of ancient Mayan art.

The Wizard as Artist

“The Wizard watches the world come and go, but his soul dwells in the realm of light…Intelligence is the glue of the universe. To the Wizard, this isn’t just a theoretical notion because he can see with his own inner eye that he is that intelligence. Mortals are baffled by such understanding since it isn’t of the mind. They are used to knowing things but not to knowingness itself…To see means to be awake to the universe’s intelligence. When the witness is fully present, everything is understood…The witness sees light. Light is a metaphor for higher states of being.”

“The Wizard watches the world come and go, but his soul dwells in the realm of light…Intelligence is the glue of the universe. To the Wizard, this isn’t just a theoretical notion because he can see with his own inner eye that he is that intelligence. Mortals are baffled by such understanding since it isn’t of the mind. They are used to knowing things but not to knowingness itself…To see means to be awake to the universe’s intelligence. When the witness is fully present, everything is understood…The witness sees light. Light is a metaphor for higher states of being.”

Bartnikowski thus found his life purpose as belonging to the historical continuum of artists who claimed that their paintings expressed spiritual powers beyond that which is visible. Through his immersion in Theosophy, he found confirmation that his art as alchemy was “true magic.” Through painting his visions of the microcosm and macrocosm came to make perfect sense. Moreover, painting proved to be the divine cathexis through which he could help mental patients. It was as if he had freed himself of Sartre’s existentialist quagmire and discovered the ultimate truth and purpose of his existence.

Man is a little world — a microcosm inside the great universe. Like a foetus he is suspended by all his three spirits in the matrix of the macrocosmos; and while his terrestrial body is in constant sympathy with its parent earth, his astral soul lives in unison with the sidereal anima mundi. He is in it, as it is in him, for the world-pervading element fills all space, and is space itself, only shoreless and infinite. As to his third spirit, the divine, what is it but an infinitesimal ray, one of the countless radiations proceeding directly from the Highest Cause — the Spiritual Light of the World.

Bartnikowski’s expression of “the Spiritual Light of the World” was reflected in thousands portraits of children and passersby, self-portraits, cityscapes, and landscapes. While his portraits certainly captured likenesses and his cityscapes resonated with urban energy, he felt their true importance was in “opening the mind to new innovative possibilities or growth in art — plus philosophical grasps of new paradigms of new beginnings to exploring the subconscious and dwellings of the minds.” At seventy-four he ruminated on why it was so difficult to part with his paintings and why, instead of marketing them, he simply had to immerse himself in the act of seeing and painting:

The meaning of time is rapidly changing inside of me. It’s whizzing by like a fly escaping the slap of death. The joy I get from the knowledge I got from my insistence on painting every day for a few decades forces me to dig deeper into my subconscious. Been working on new techniques in many different areas and the excitement of it energizes my nervous system — especially in portraiture….I’ve painted approximately 180 self-portraits over a span of 44 years [since 1956]. Many were done on a Holiday; that is, New Years, Christmas, Thanksgiving. I’ve learned it’s best for me to be alone working during the Holidays. There are times I deviate from this paradigm, regrettably so. It’s peaceful to omit the frenzy of the holidays. Besides, I’ve been in a creative mode the past 3?–4 months and feel I’ve been somewhere between earth and the edge of the universe. I still toy with the idea of having a big solo show here in New York and it haunts me on occasions — and then it passes like a drifting cloud in blueness. So, if at all possible, would like to keep track of all of my painting — especially the palette knife ones — they’re very meaningful to me — and my psyche. Actually, when I meditate and reminisce my original intention was to learn color as I felt inadequate in it since the fifties, before that to back in the twenties — for there my struggle tied in to line more than value and form — and color was a giant step ahead of me — and I knew unless I forgot myself it would be almost impossible to accomplish what I felt I wanted way deep in my bones. To comprehend this further, cyberspace has once again engulfed me like quicksand. [11/19/2000]

As a humanist, Bartnikowski’s approach to studying art history was rooted in empathy. His notes describe the “rapturous state of ecstasy” expressed in Raphael’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria and the serenity in Perugino’s portrait of Saint Mary Magdalene. And, as he strove for “self-forgetfulness” he was greatly impressed by Monet’s automatic response of analyzing color even when painting Camille Monet on her deathbed of 1879. “Monet is to some extent escaping the pain of a beloved’s death by externalizing it but it is, nonetheless, a remarkable act of egoless activity. In itself, this self-forgetfulness is the essence of true commitment.”

From the Old Masters to the French Post-Impressionists the painting styles he admired most were fresh and spontaneous. He held particularly high regard for Adolphe Monticelli [1824-1886], whose rich colors, style, and sparkling surfaces prefigured and influenced that of his much younger friend, Vincent van Gogh [1853-1890]. Both artists’ were “painters’ painters,” consumed by their art, and died impoverished.

In turning to the Far East, he discovered that the inspirational qualities of his favorite Western paintings were confirmed in tankas — the large colorful works painted by Tibetan monks referring to Buddha. Owing to these paintings’ ability to induce meditative states and evoke psychosomatic forces, they served a higher role as tools for enlightenment rather than self-expression. But in order to achieve such powerfully positive effects Bartnikowski had to sublimate and ultimately bury his ego, which he referred to as a “false self.”

Whether painting on street corners or in backyards, or inside bars and laundromats, Bartnikowski stressed the importance of observational drawing. Even when immediately applying the palette knife alla prima to his favorite support — side panels cut from milk and orange juice cartons — he deeply contemplated the scene beforehand. Although some of these small panels — pochades — may appear as abstractions, his skillful use of the palette knife conceals the intense observation of their maker, who wrote that “The disassociation of the abstracted elements of a visual language from direct visual perception of reality has obscured the value these elements possess in the education of the eye to observe and understand tangible, physical bodies in space.”

He was also aware that his writing would not be as effective as the visual language of his paintings unless he exerted the same careful concentration in selecting his words. “Intentions compressed into words enfold magical power,” he wrote. “Once a word’s intention is absorbed, a spell has been cast in the form of a mental imprint. Our whole lifetimes are packaged inside us as imprints triggered by words. Mortals are wrapped in words the way a spider wraps flies in gossamer — Only in this case you are both spider and fly because you imprison yourself in your own web.”

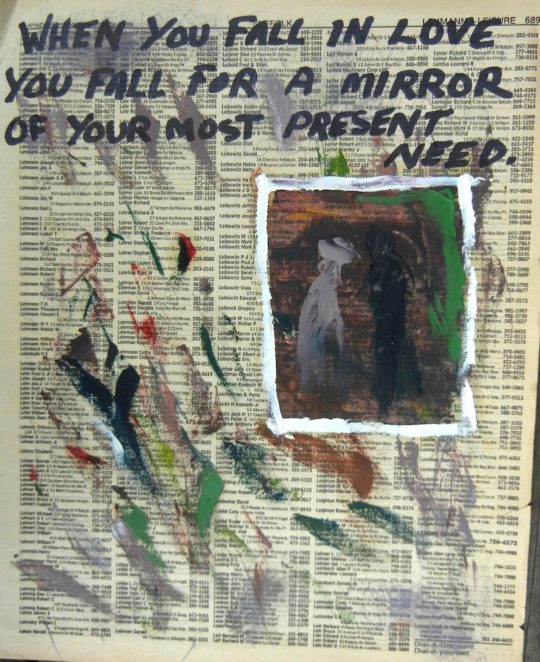

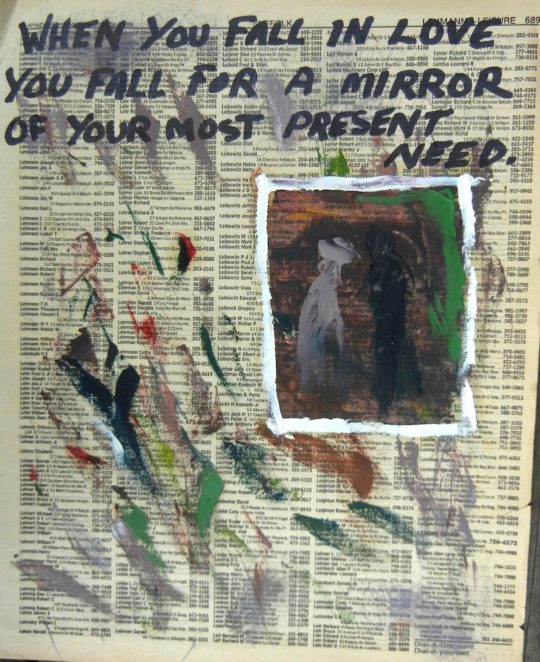

The analogy of the spider and fly was not lost upon Bartnikowski when it came to love. Although many of the models that posed for him were also his lovers he never married. One of his favorites was Clair, who he referred to as “a glutton for love” but noted that “Passionate romantic love is like a flower while marriage is like a hard gem that endures…the gem of mutual peace emerging from the wild chaos of love.” Continuing, he lamented Clair’s “spiritual emptiness” as he experienced how “The magnificence of a sacred relationship crashes on the rocks of trivial ego conflicts.” Ultimately, the artist’s noble quest could not be impeded or jeopardized by the struggle between love and ego. The Wizard’s mission, like that of a monk, would not accommodate marriage. “When you fall in love,” he wrote, “you fall for a mirror of your most present need.”

The Final Dream of the Waking Dreamer

As you think so shall you be. By becoming a waking dreamer you will enter the higher level of consciousness beyond waking consciousness. Keep reminding yourself that you are a multi-dimensional being…The Wizard uses words to say yes to things we have been taught to say no to…In the case of mortals, the messages are garbled and confused. In the case of Wizards they are crystal clear…The Wizard watches the world come and go, but his soul dwells in the realm of light…Intelligence is the glue of the universe. To the Wizard, this isn’t just a theoretical notion because he can see with his own inner eye that he is that intelligence. Mortals are baffled by such understanding since it isn’t of the mind. They are used to knowing things but not to knowingness itself…To see means to be awake to the universe’s intelligence. When the witness is fully present, everything is understood…The witness sees light. Light is a metaphor for higher states of being.

Bartnikowski would likely have been amused that the cause of his death remained a mystery. Just as he saw his birth as “scattering stars like dust” so upon death his physical body returned to dust — even a stardust. “Death is not a punishment but a transition,” he wrote. “The only thing that dies is form, while thought is eternal energy. You are that thought, and it can never die. Surrender completely and stop fighting anything and everything. When you have this trust you will wonder why you did not surrender long ago because of the peace and serenity you will feel…In unity of consciousness we slip through the barrier of time into the playground of eternity.”

Psychoanalysts would likely determine that Bartnikowski found it difficult to part with his thousands of paintings because he fit the profile of a classic reclusive hoarder. But his reality was that they collectively formed the ultimate cathexis, and he referred to them as his “exquisitely orchestrated onesong.” On the back of an envelope the man who was the master artist wrote, “In my mind all my palette knife paintings are like jewels; they are somehow mysteriously and miraculously beaded together to form a web of my life.” On still another envelope, the man who was the Wizard wrote:

“There is a falling star in my room — my lights are all off.”

— Peter Hastings Falk

Addendum

A Codex to Bartnikowski’s Writings

A Codex to Bartnikowski’s Writings

This codex is necessary in order to translate Bartnikowski’s voluminous writings.

a with the right leg flaring to the right means “at”

b = be

B = body

bcz = because

c = see

cld = could

condi = condition

cons = consciousness

dis = distance

gro = grow

hier = higher

hu = human

hv = have

emo-s = emotions

ex- = example

exper = experience

exp-ces = experiences

L backwards (looking like a reverse check-mark) means “the”

L backwards (looking like a reverse check-mark) but with an “m” added = them

L backwards (looking like a reverse check-mark) but with an “y” added = they

L backwards (looking like a reverse check-mark) but with an “tre” added = there

L backwards (looking like a reverse check-mark) but with an “refr” added = therefore

lite = light

lo = love

levg = leaving

M = Merlin

mo = money or more

nat-l = natural

not-g = nothing

psychol-l = psychological

phyzl = physical

peo = people

prob-s = problems

r = are

rela-p = relationship

sex-l = sexual

spi = spirit

spir-l = spiritual

surr = surrender

tk = take

V with the right leg flaring to the right means “that”

V with the right leg flaring to add “ru” means “through”

V with the right leg flaring as a “Y” means “they”

W with the right leg flaring to the right means “what”

w-in = within

whl = while

wi = with

wil = will

Wiz = Wizard

wo = woman

Xs = times

y = you

yor = you are

Visionary: The Wizard of Brooklyn

-

DETAILS

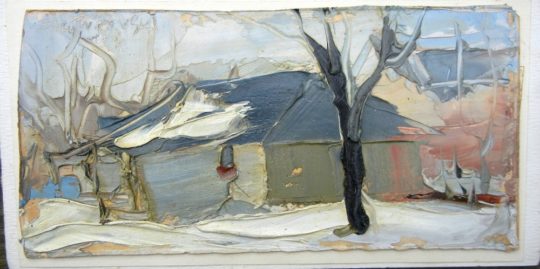

DETAILSA Garage under Snow, 1982

7.5 x 3.5 inches (19.05 x 8.89 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSA Lane at the Hospital in Summer, 1975

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAlex, 1982

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlack Pickup, 1979

9.5 x 8.5 inches (24.13 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

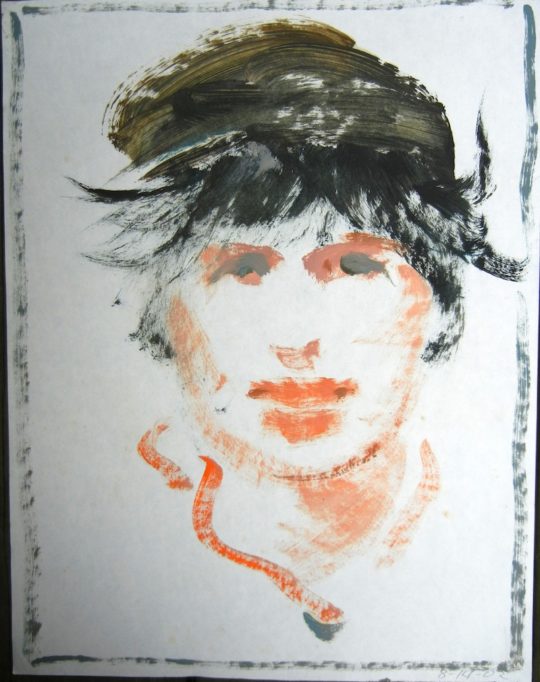

DETAILSBlonde-haired Woman, 1978

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

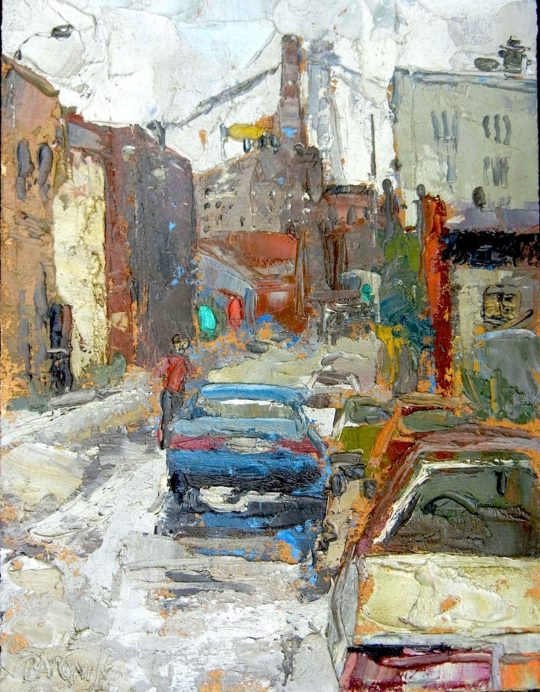

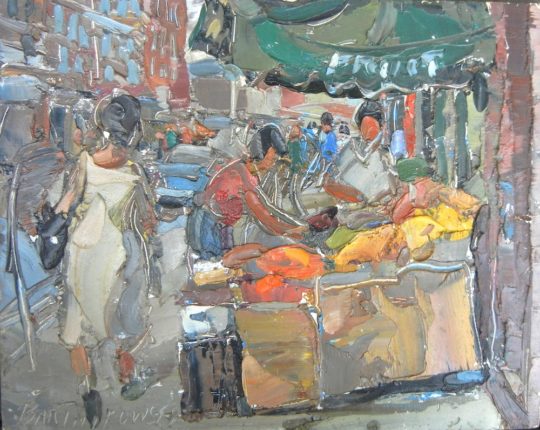

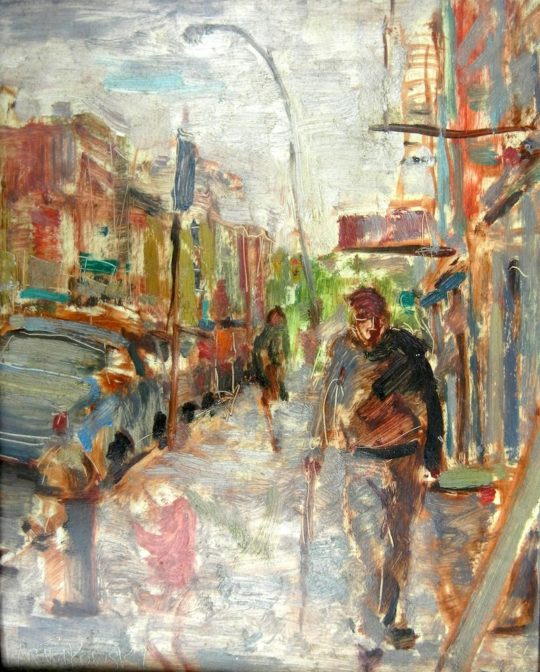

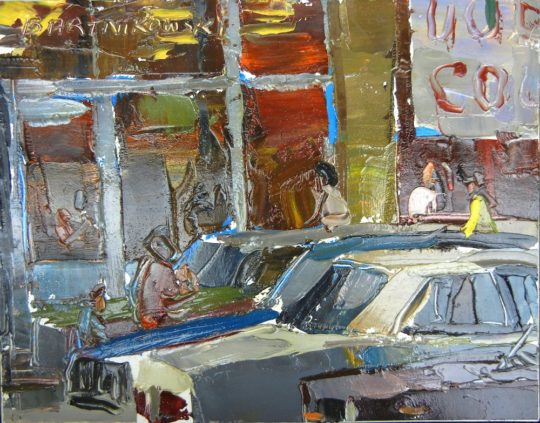

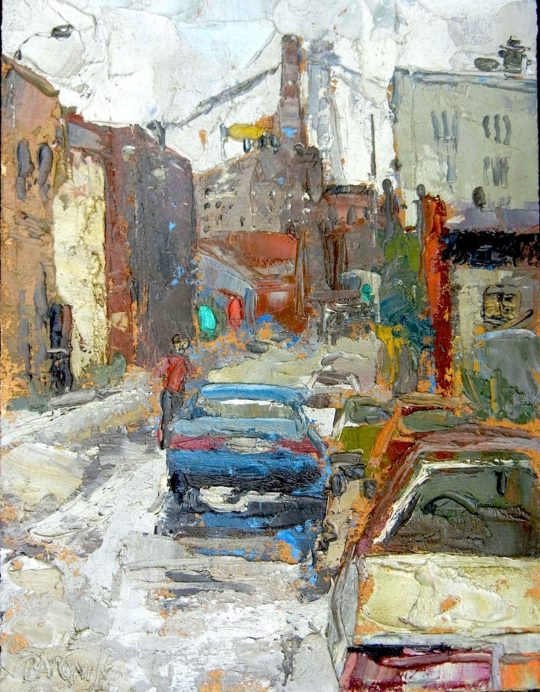

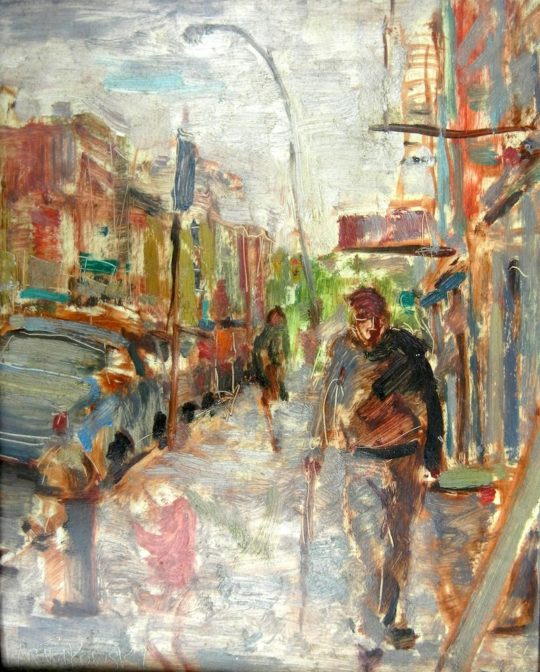

DETAILSBrooklyn Street Scene, 1984

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.32 cm) -

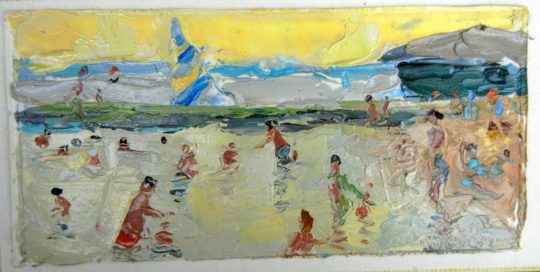

DETAILS

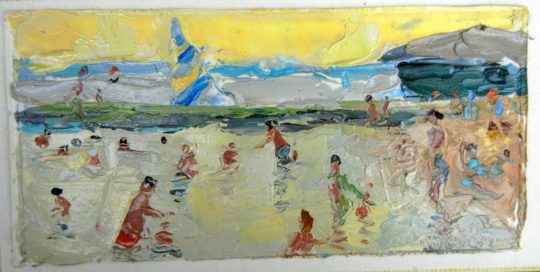

DETAILSEast Islip Beach, 1990

9.5 x 7.5 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEast Islip Beach, 1999

7.5 x 3.5 inches (19.05 x 8.89 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGreenpoint Avenue, Brooklyn, 1978

10 x 8.5 inches (25.4 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

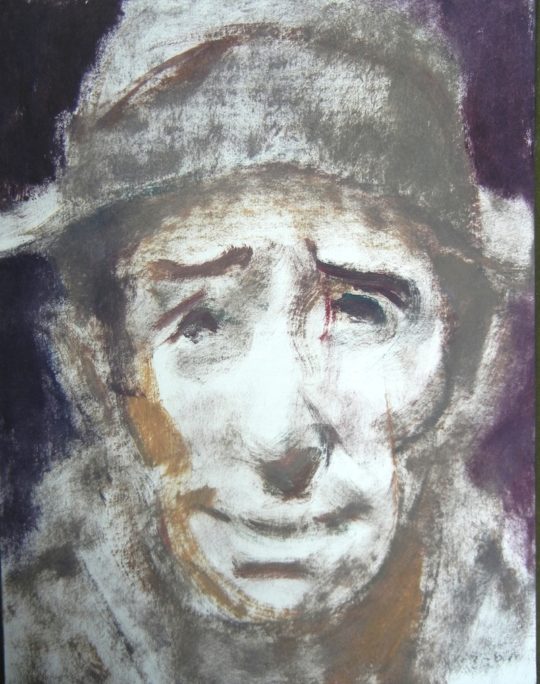

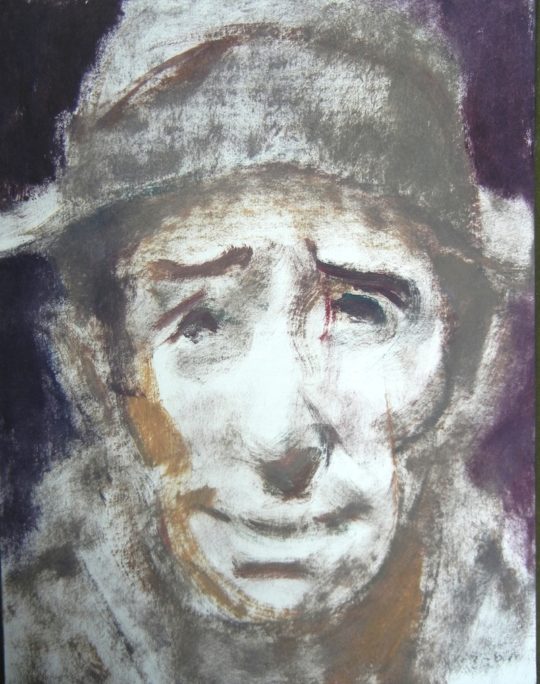

DETAILSMan with Hat, 2001

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

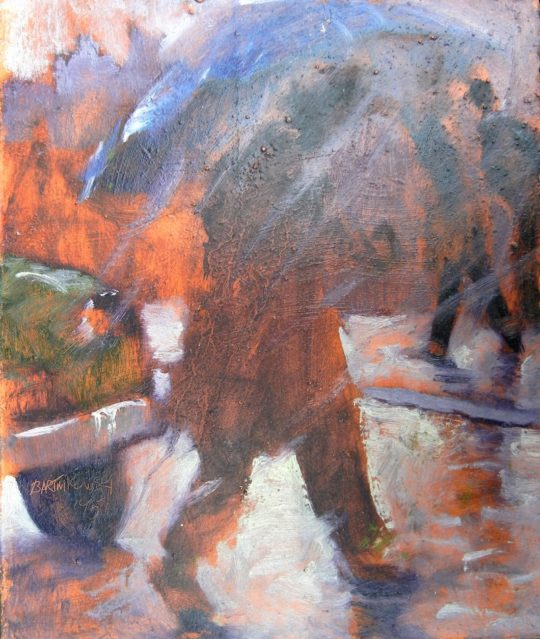

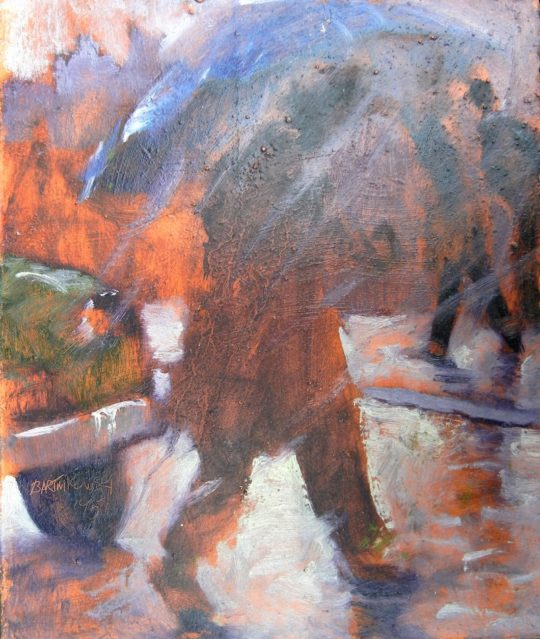

DETAILSMan with Umbrella, 1994

9.5 x 11.5 inches (24.13 x 29.21 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSManhattan Avenue, Brooklyn, 1979

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

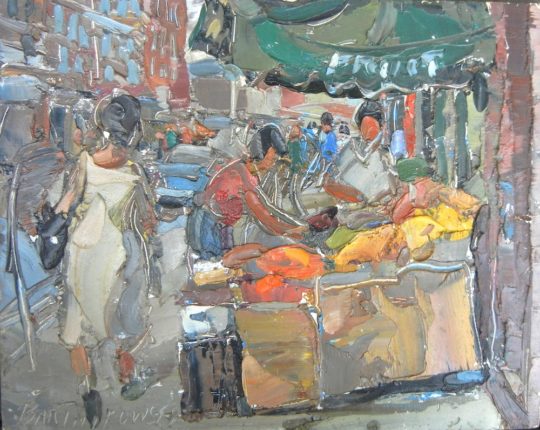

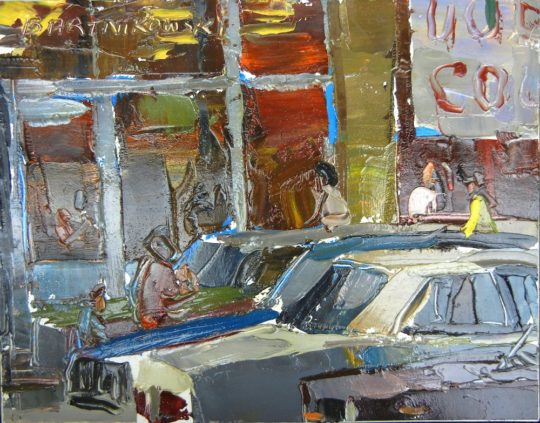

DETAILSMarketplace, Brooklyn, 1980

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMezzarole Avenue, Brooklyn, 1979

9.5 x 7.5 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

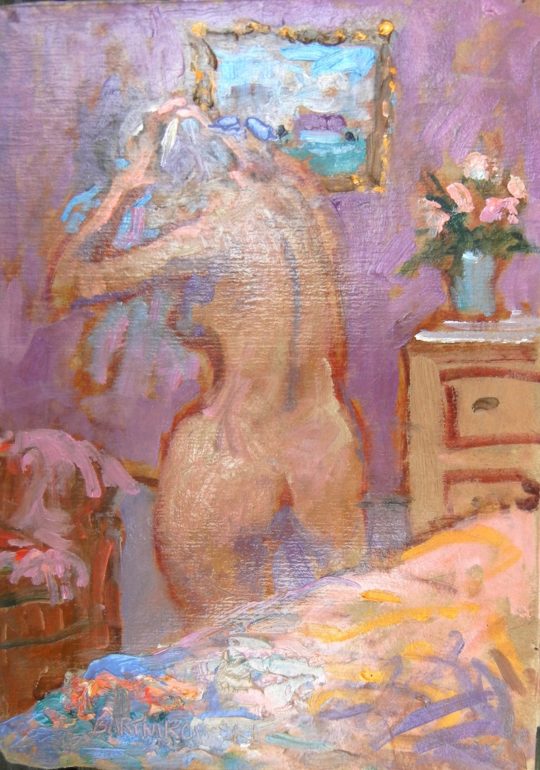

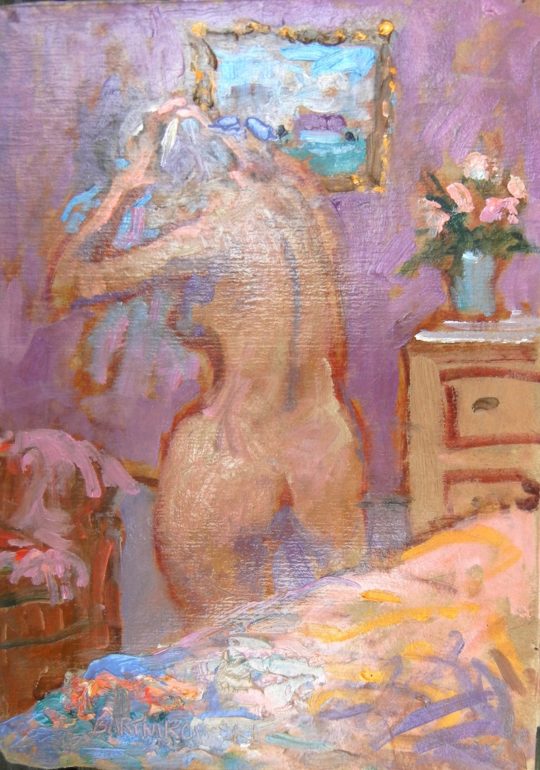

DETAILSNude (in bedroom), 1996

7.5 x 10 inches (19.05 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

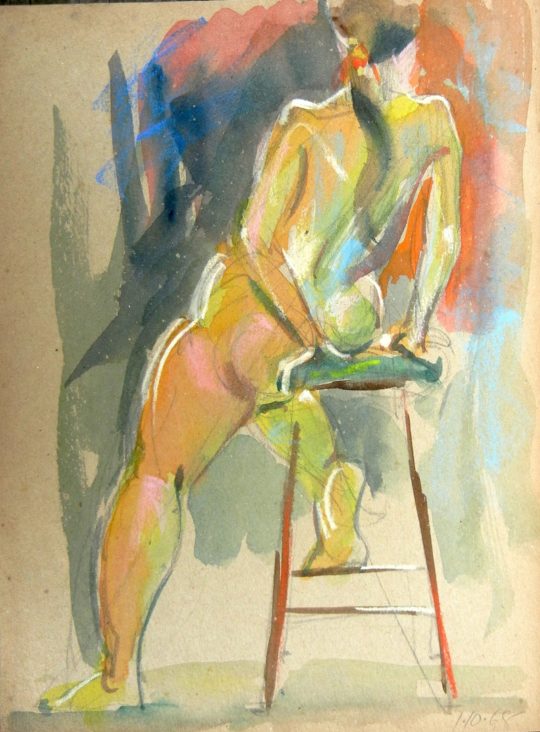

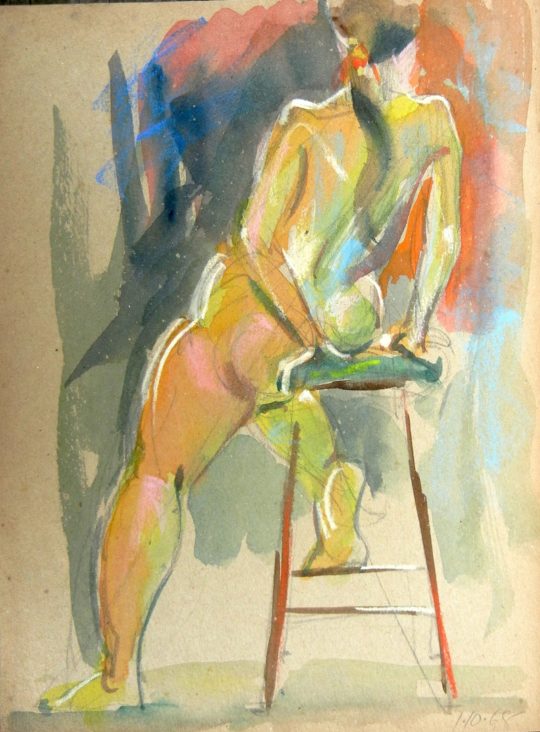

DETAILSNude (on stool), 1968

9 x 12 inches (22.86 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

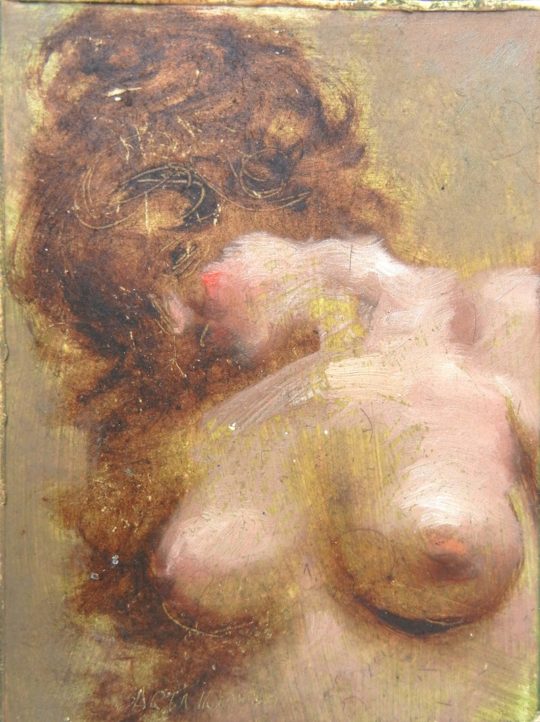

DETAILSNude (profile torso), 2004

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

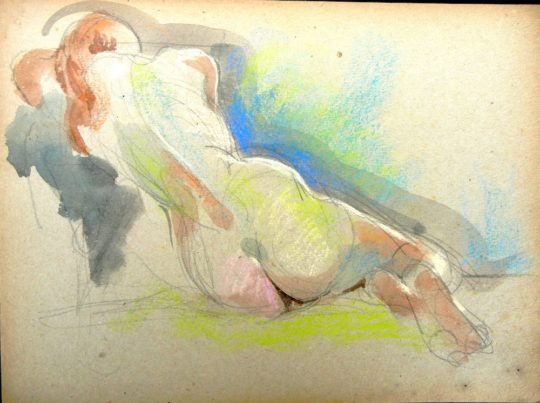

DETAILSNude (profile torso), 1968

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

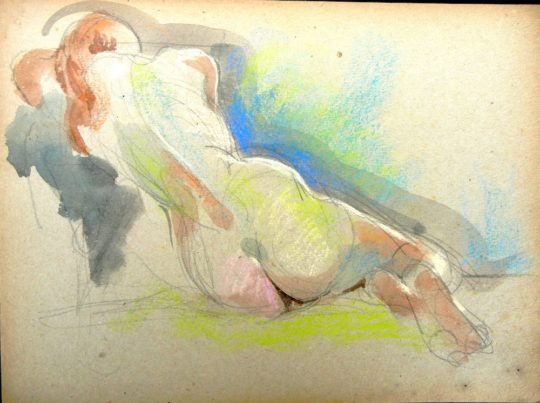

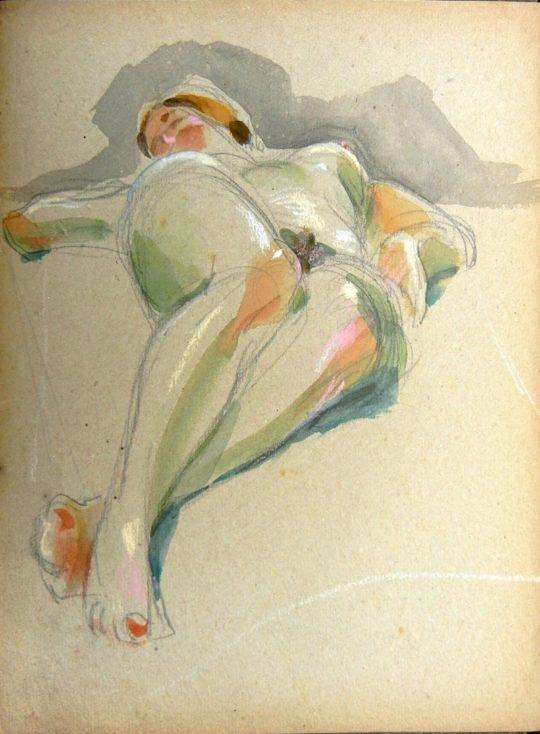

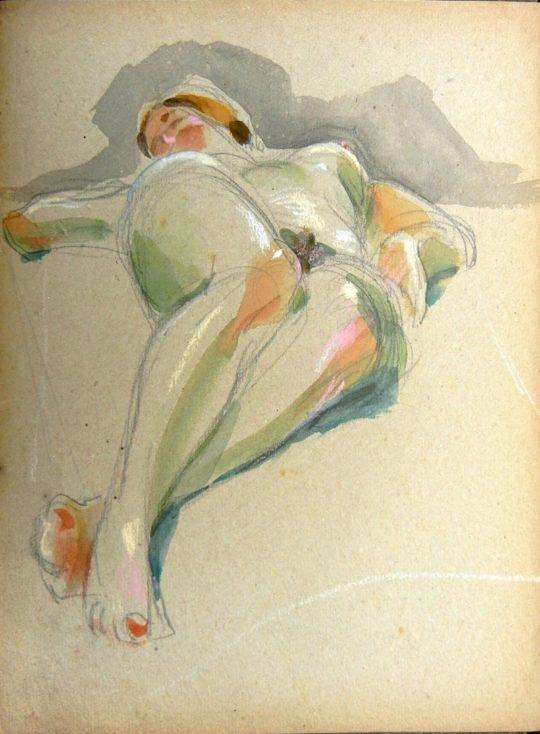

DETAILSNude (reclining), 1968

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

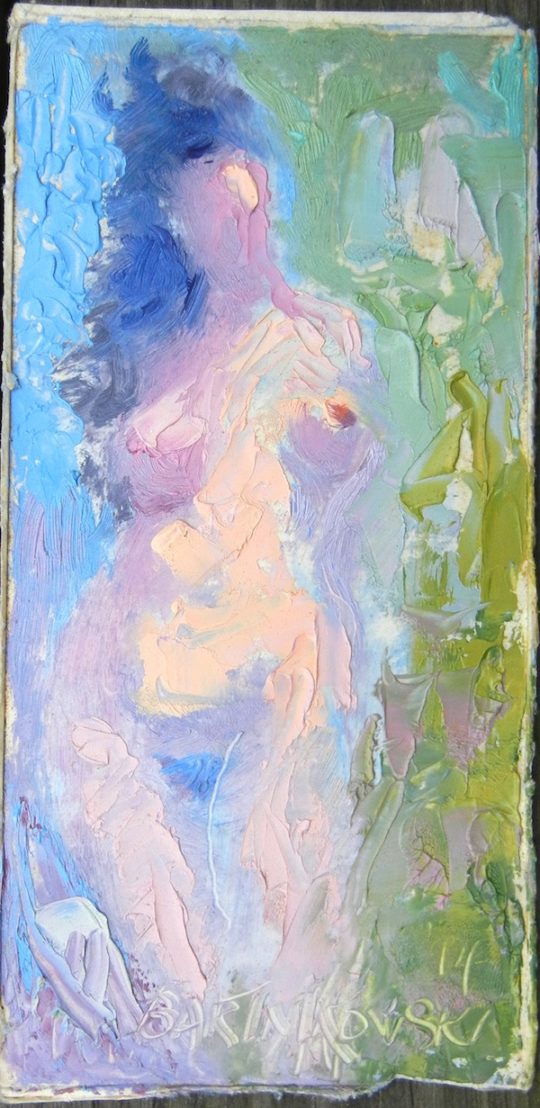

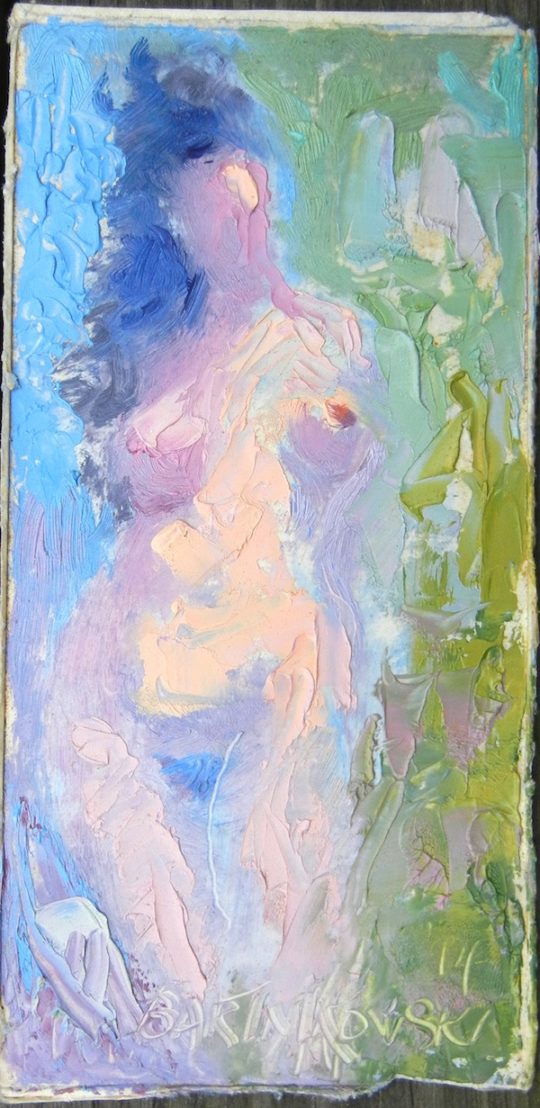

DETAILSNude (standing frontal), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

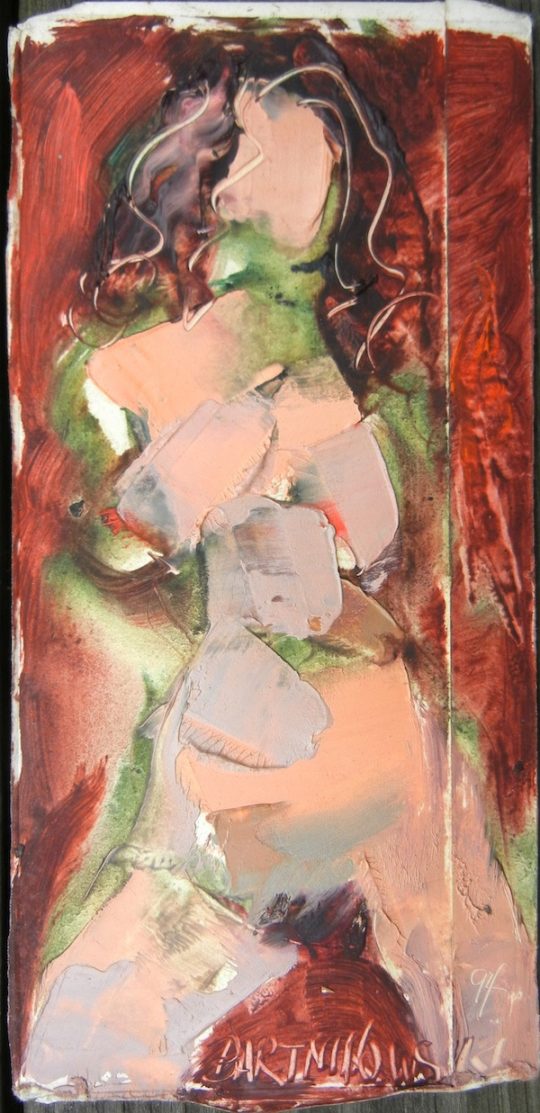

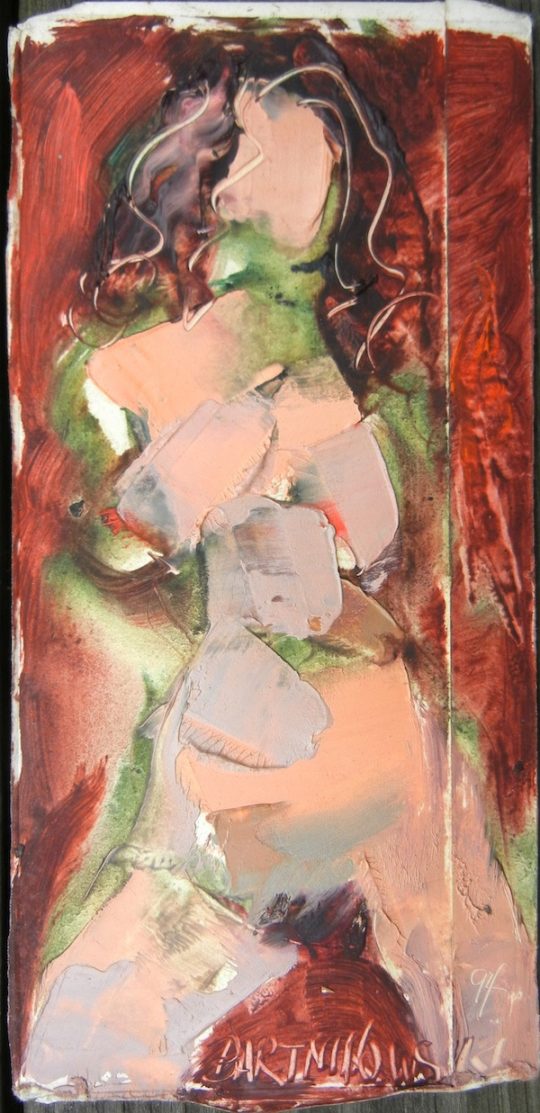

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (standing frontal), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (standing frontal), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

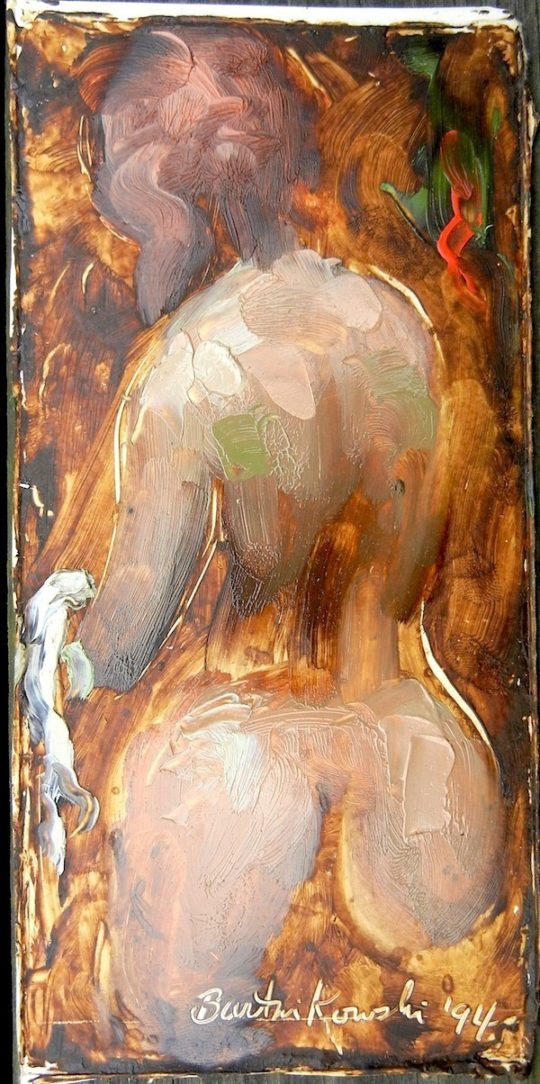

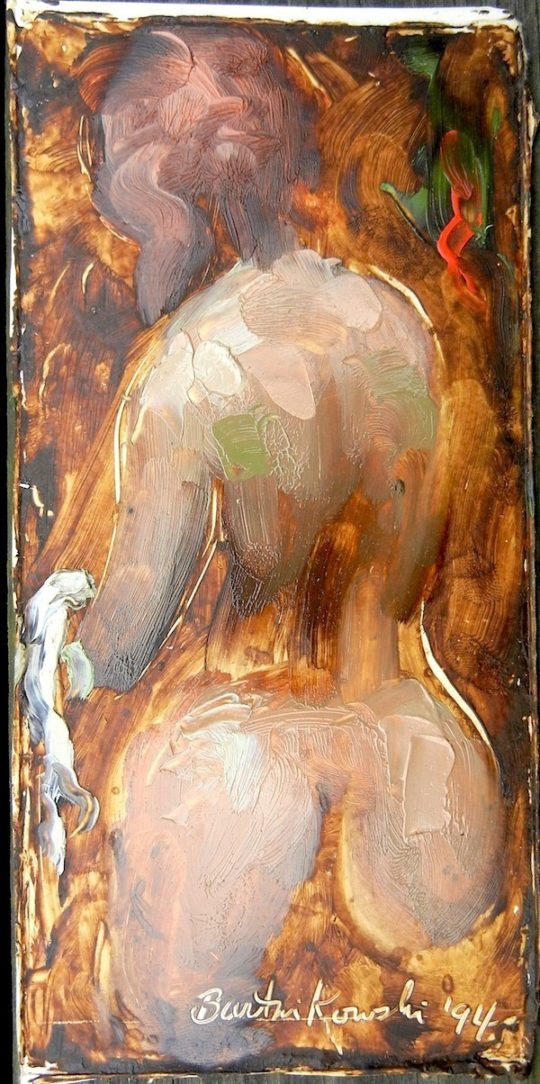

DETAILSNude (standing posterior), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

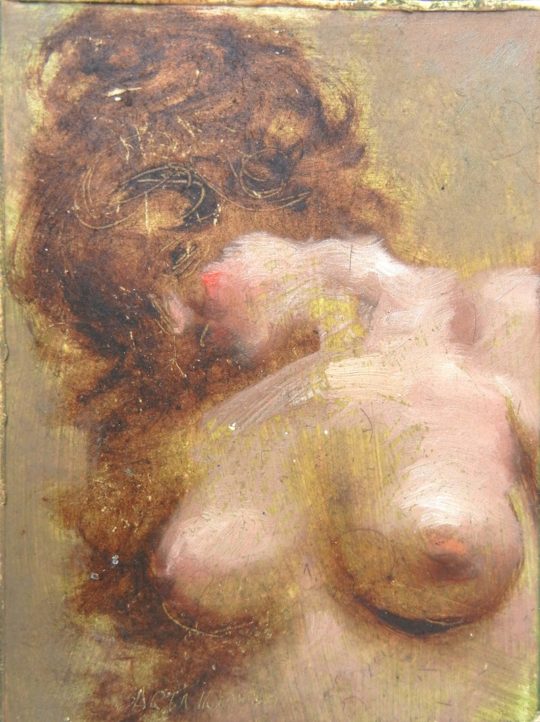

DETAILSNude (torso), 1983

3.5 x 5 inches (8.89 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

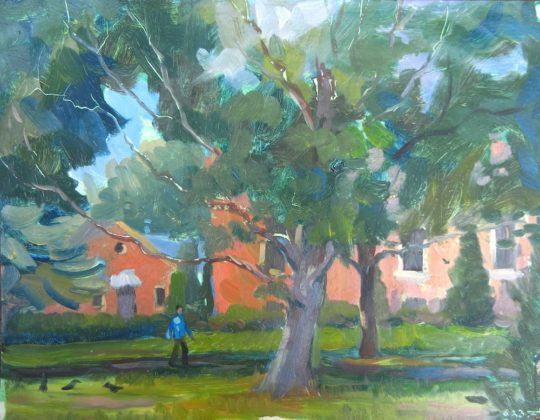

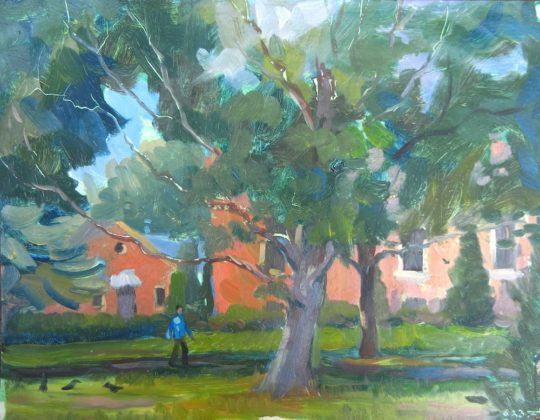

DETAILSOn the Hospital Grounds in Summer, 1975

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

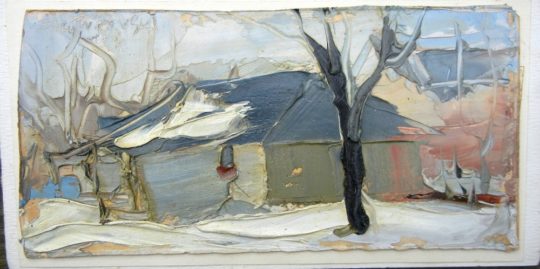

DETAILSOutbuildings in Snow, February, 1978

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPark Entrance, Brooklyn, 1988

30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

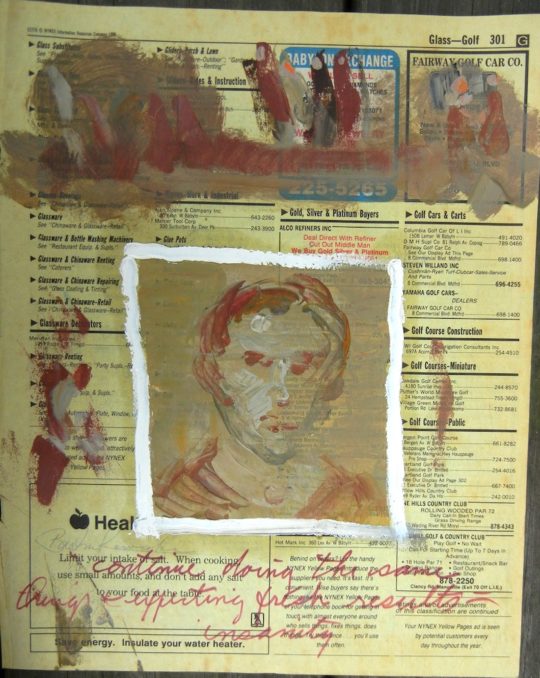

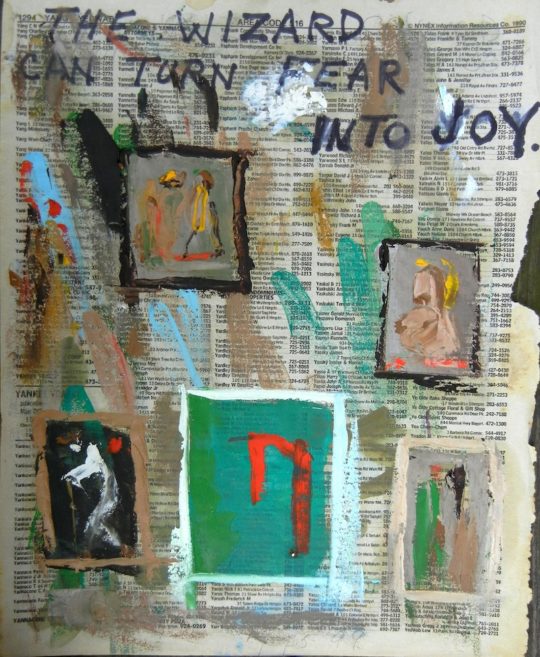

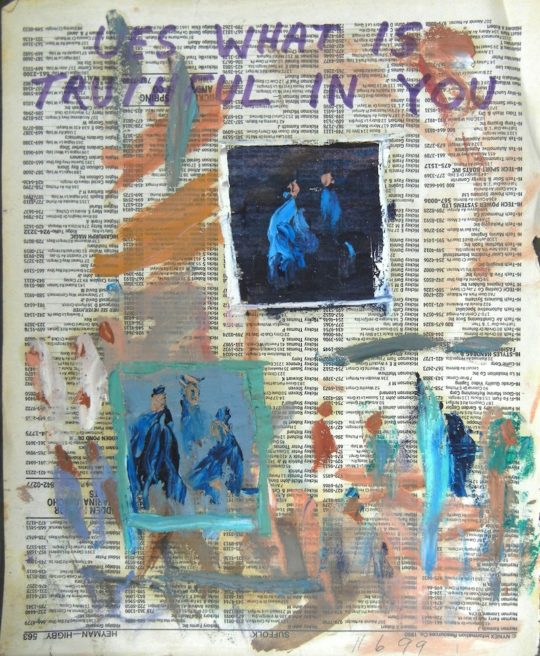

DETAILSPhonebook Page 1294, 1999

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

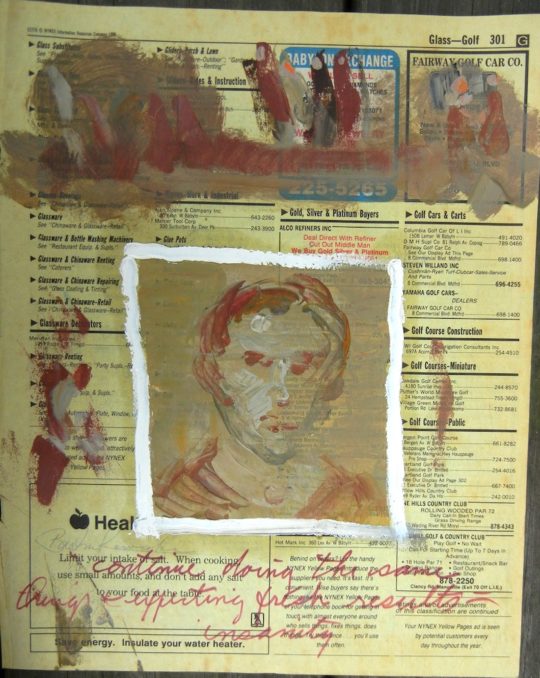

DETAILSPhonebook Page 301, 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

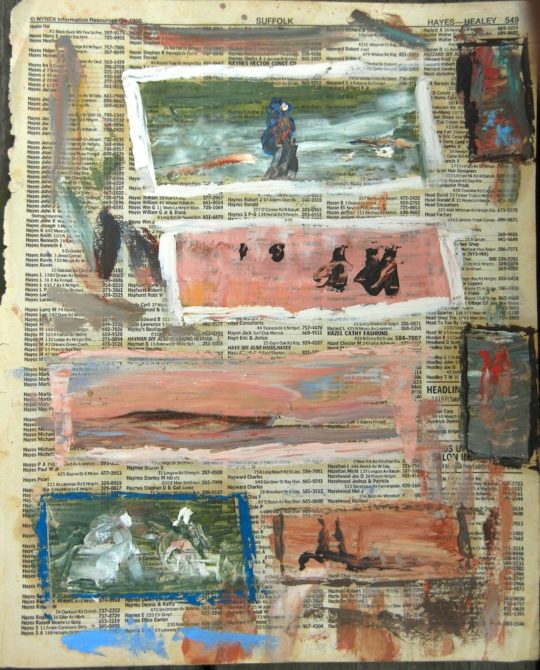

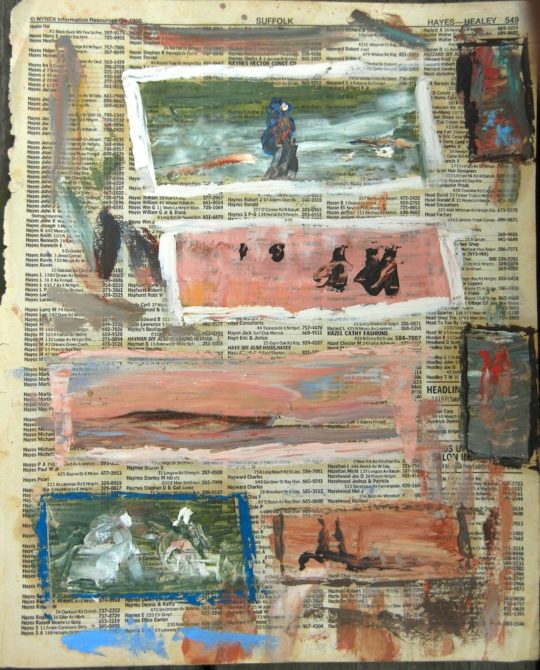

DETAILSPhonebook Page 549, 1990

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

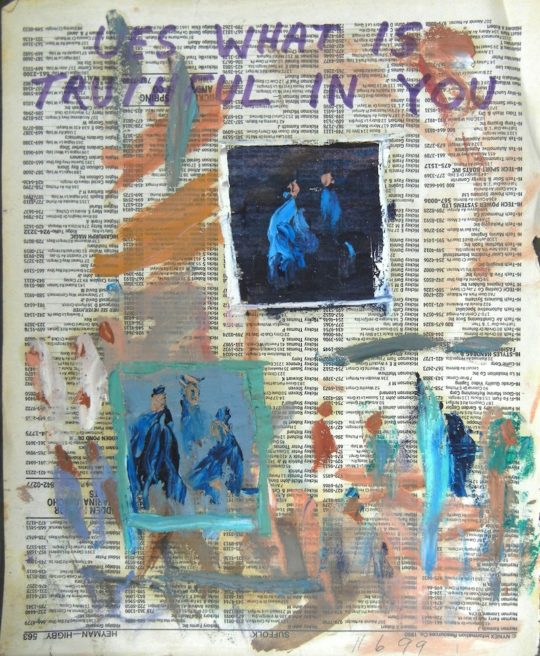

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 563, 1999

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

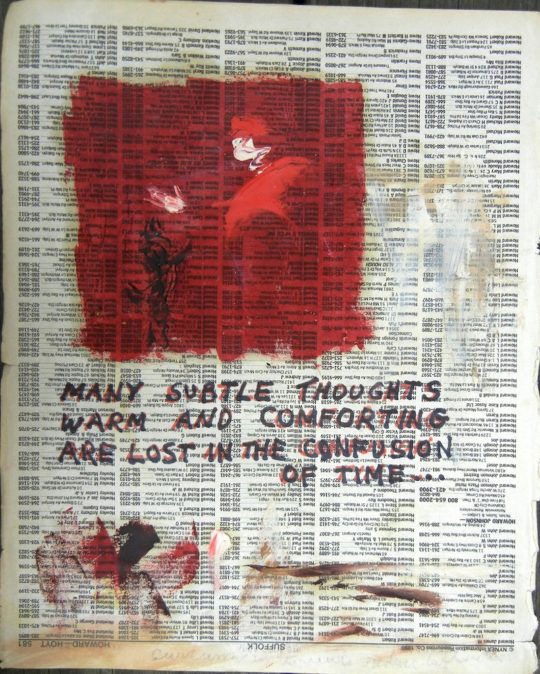

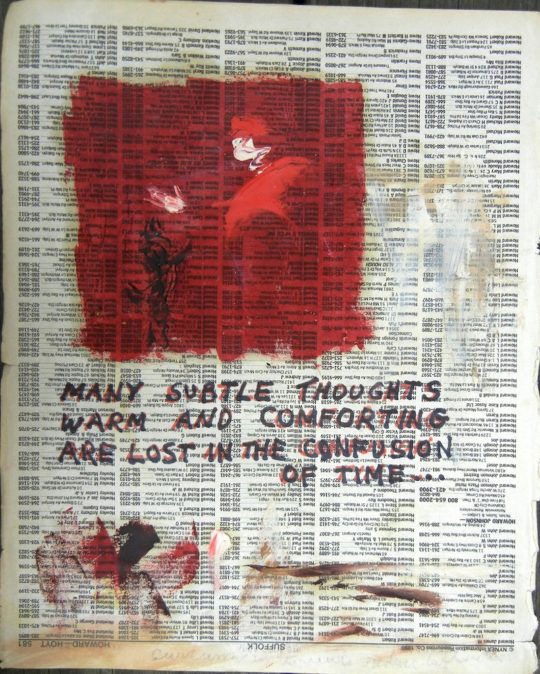

DETAILSPhonebook Page 581, 1985

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 689, 2001

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 717, 1999

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

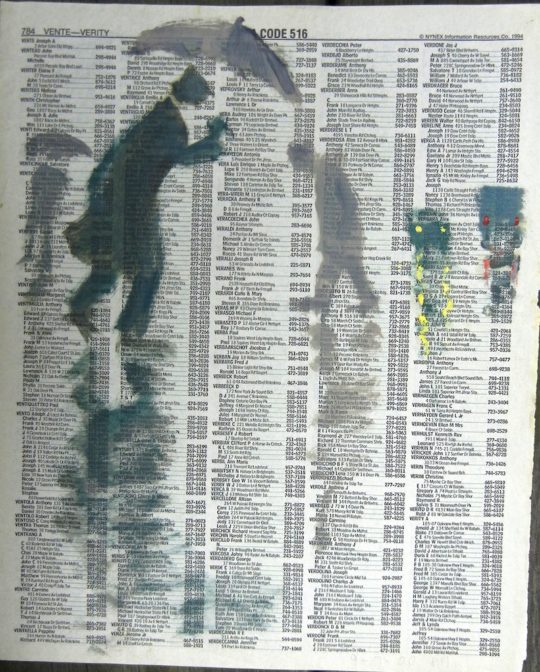

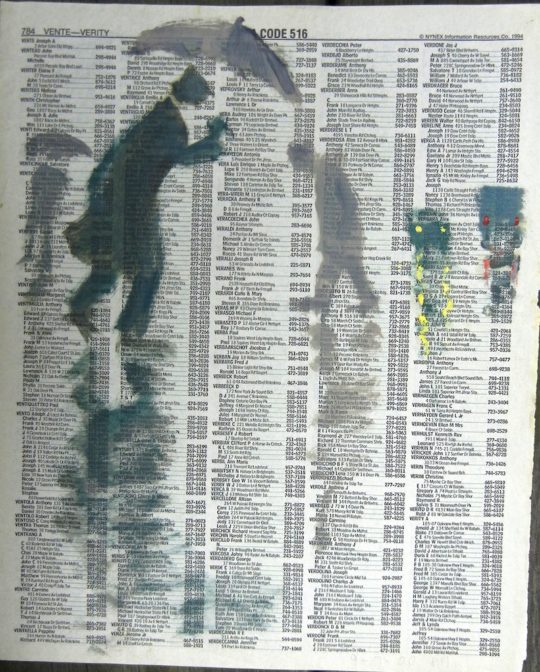

DETAILSPhonebook Page 784, 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

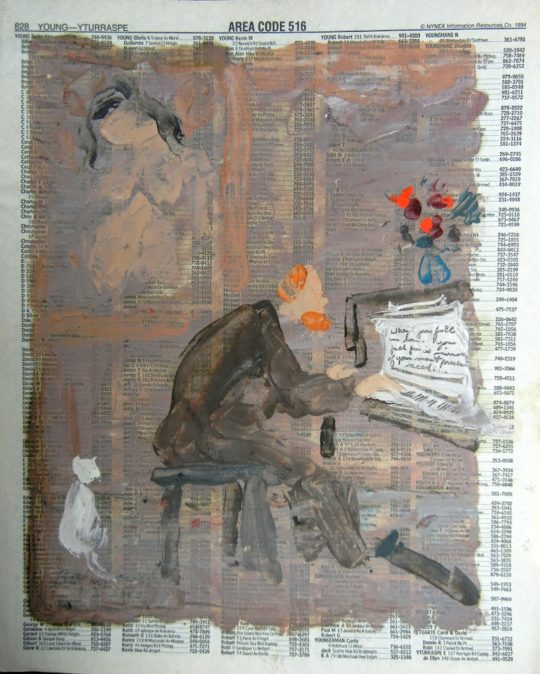

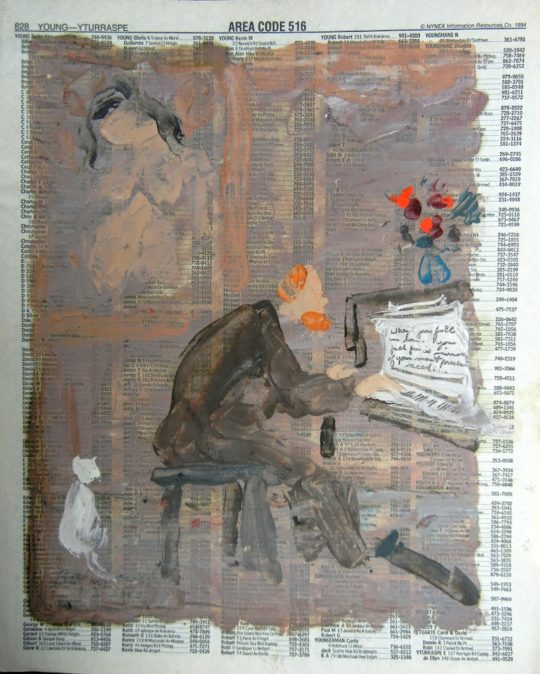

DETAILSPhonebook Page 828 (Pianist), 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

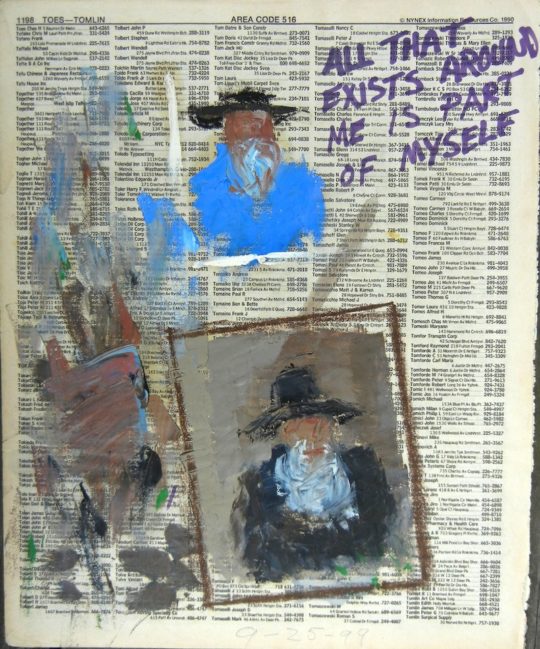

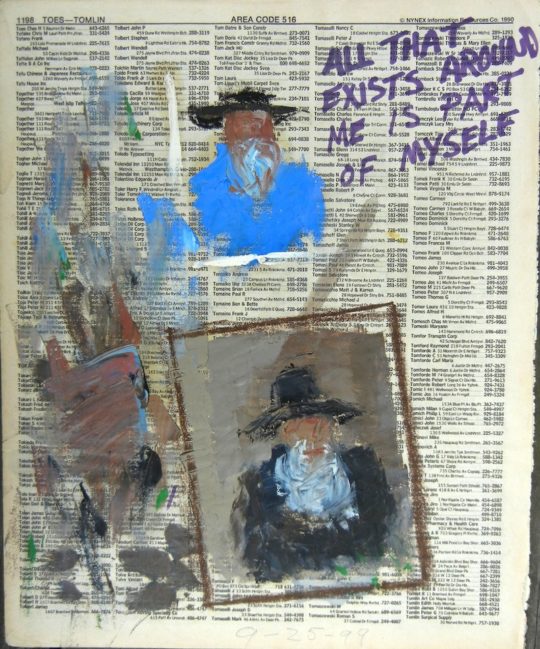

DETAILSPhonebook Page: 1198, 1999

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

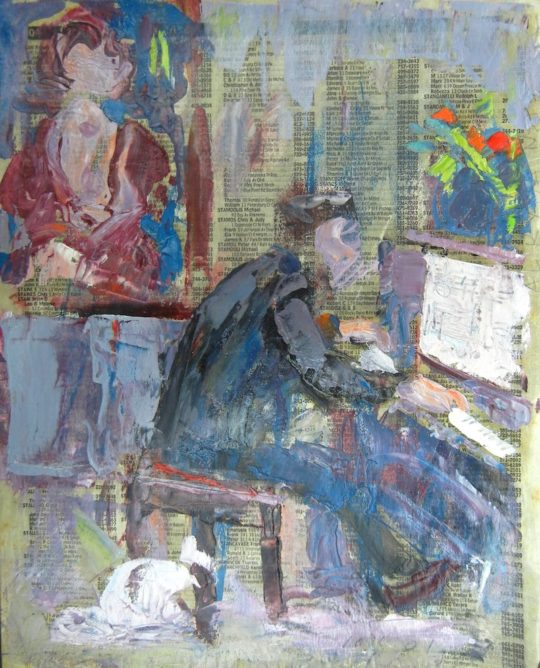

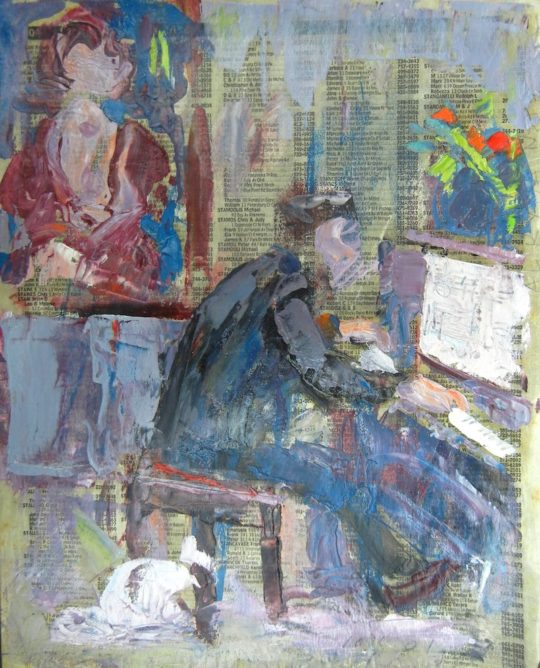

DETAILSPhonebook Page: Pianist, 2001

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

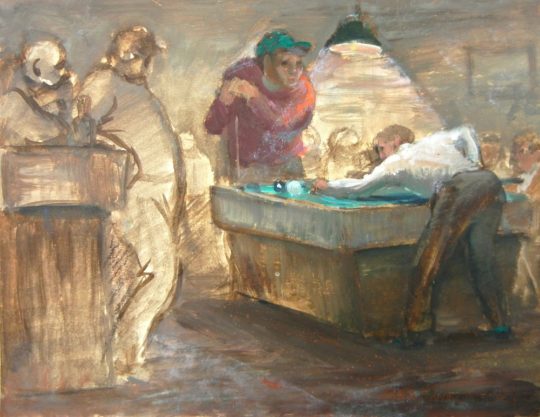

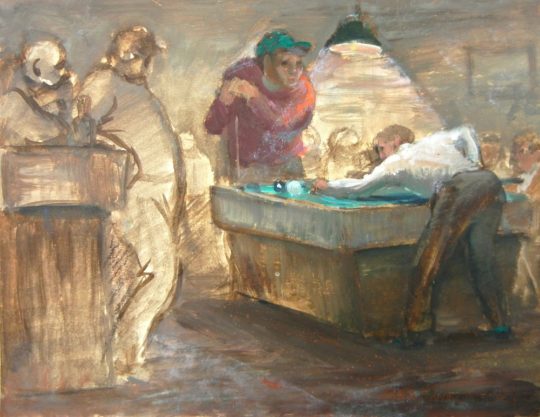

DETAILSPool Players in a Brooklyn Bar, 1980

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait of a Young Man Screaming, 1985

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

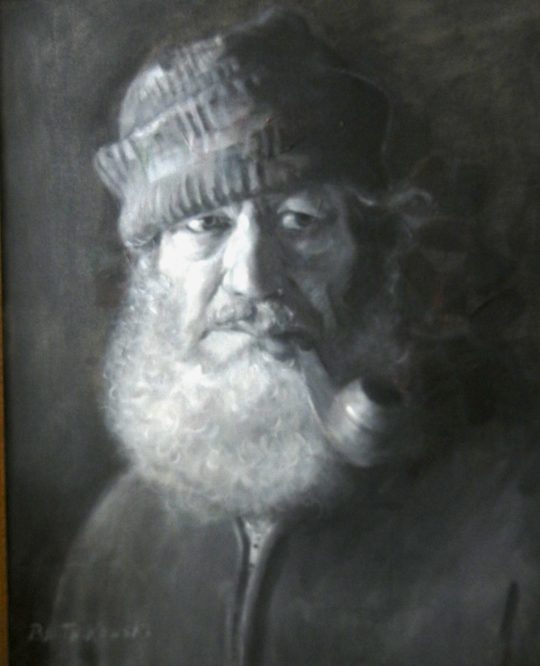

DETAILSRabbi, 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

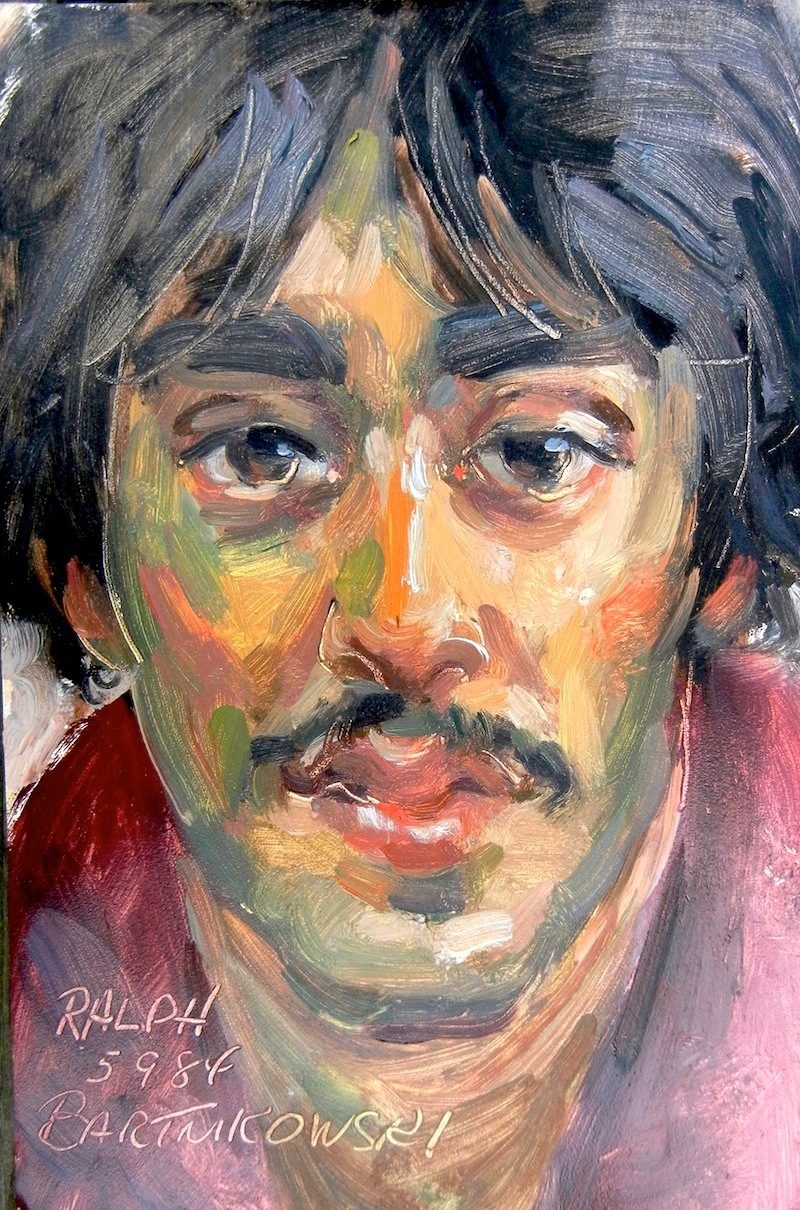

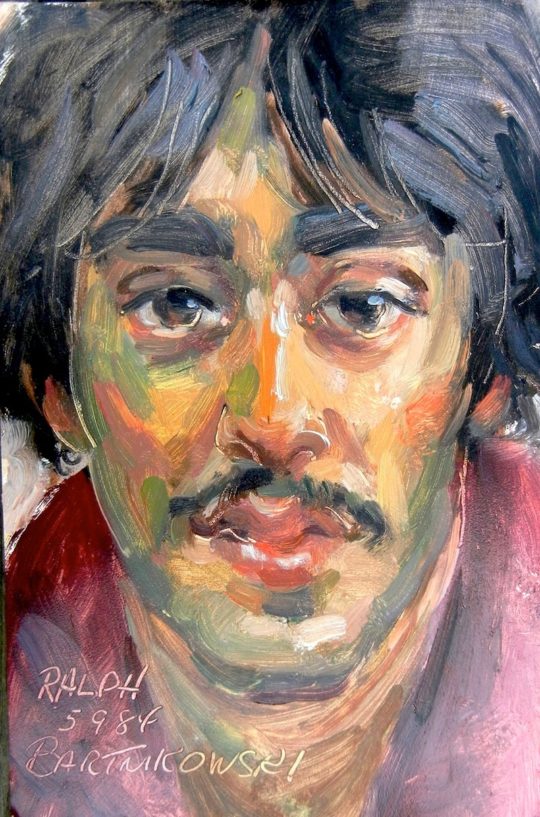

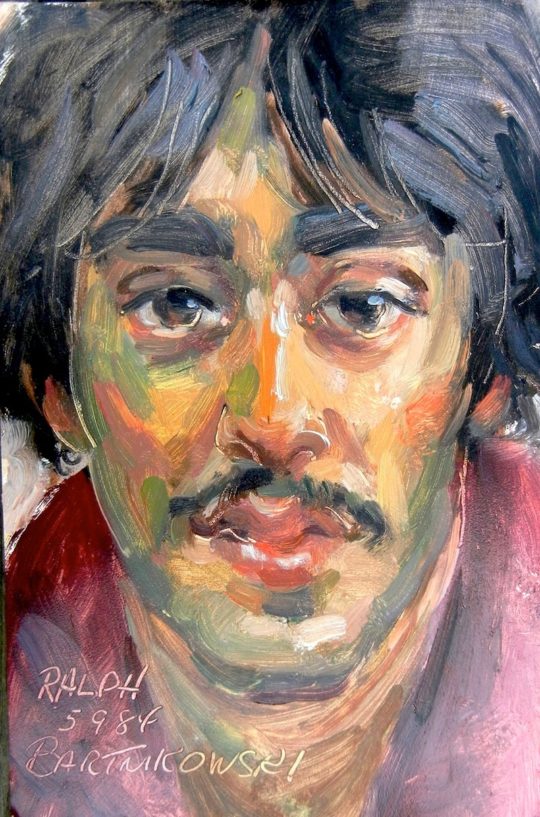

DETAILSRalph, 1984

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

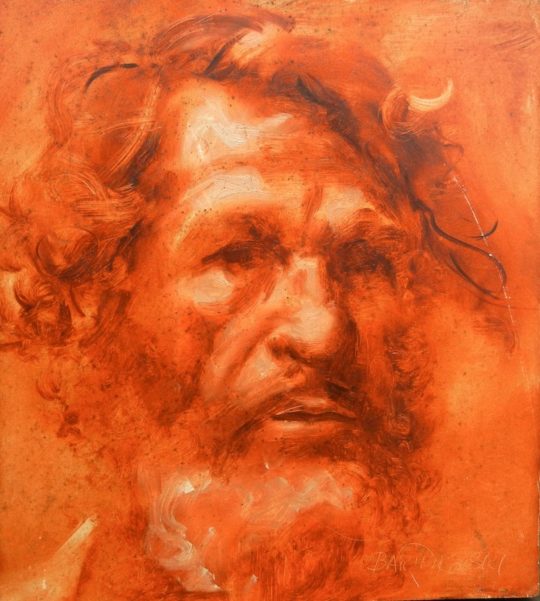

DETAILSSelf-portrait, 1987

10 x 11.5 inches (25.4 x 29.21 cm) -

DETAILS

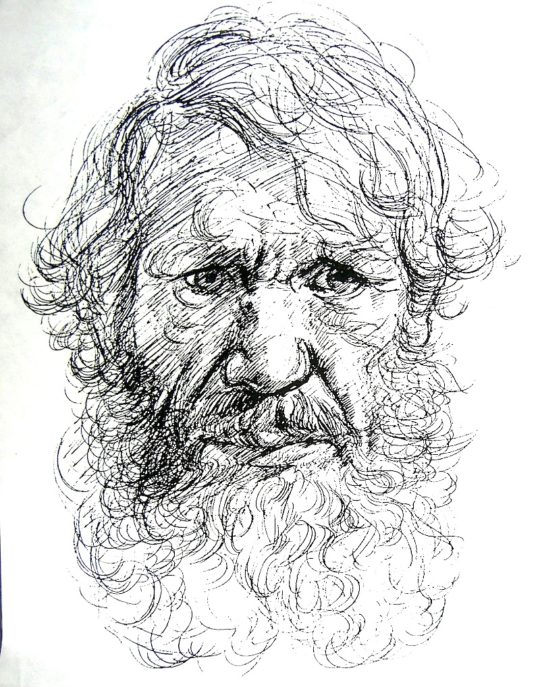

DETAILSSelf-portrait (as Leonardo da Vinci), 1990

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

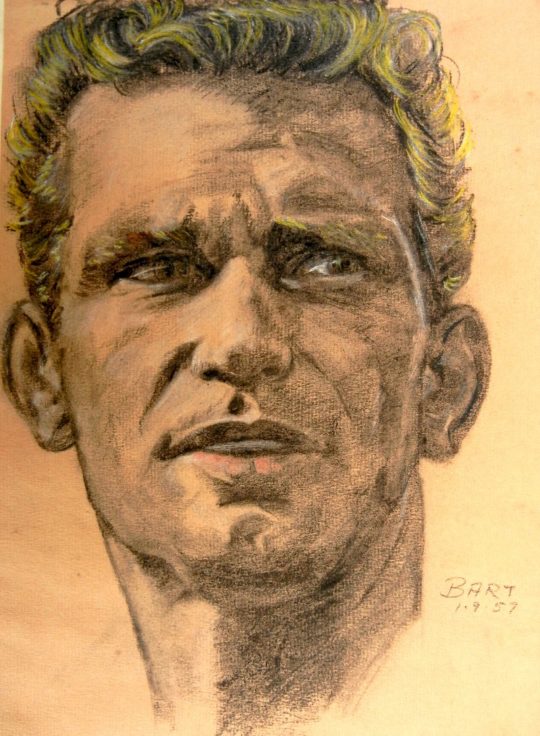

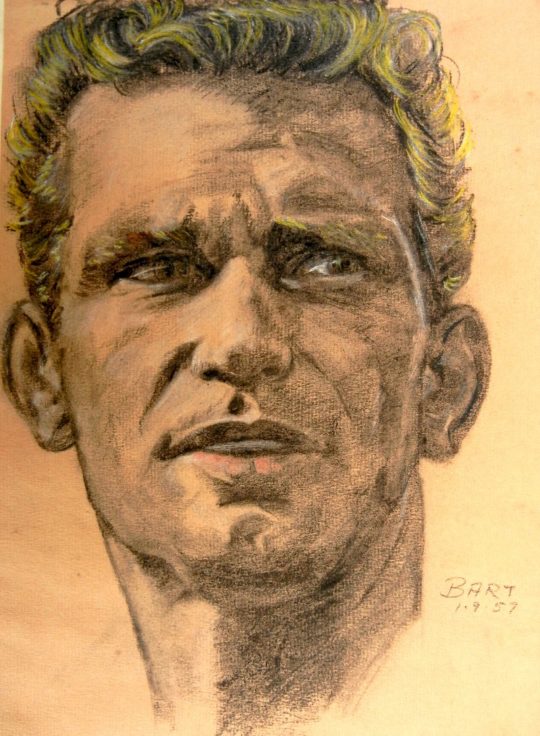

DETAILSSelf-portrait at 31, 1957

9.5 x 12.5 inches (24.13 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

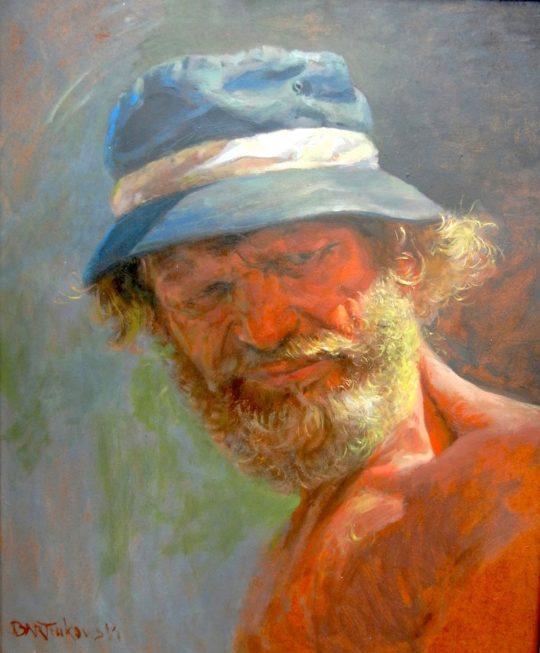

DETAILSSelf-portrait in Blue Hat, 1980

20 x 24 inches (50.8 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait in Hat, 1978

14 x 18 inches (35.56 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

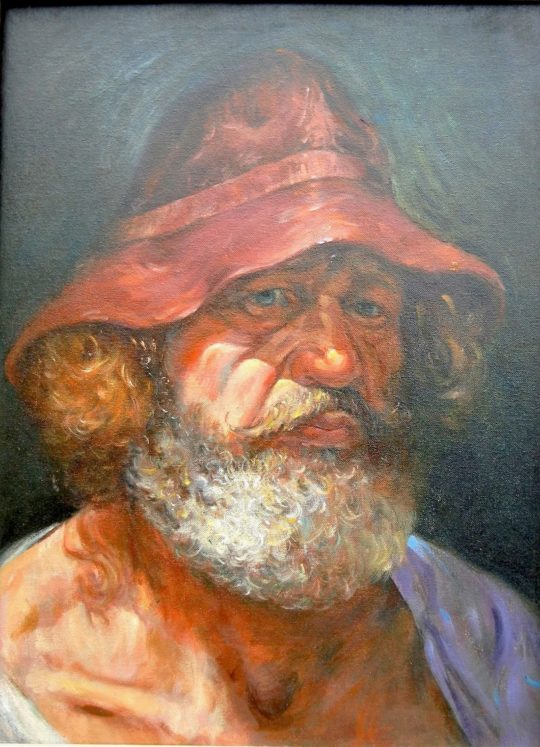

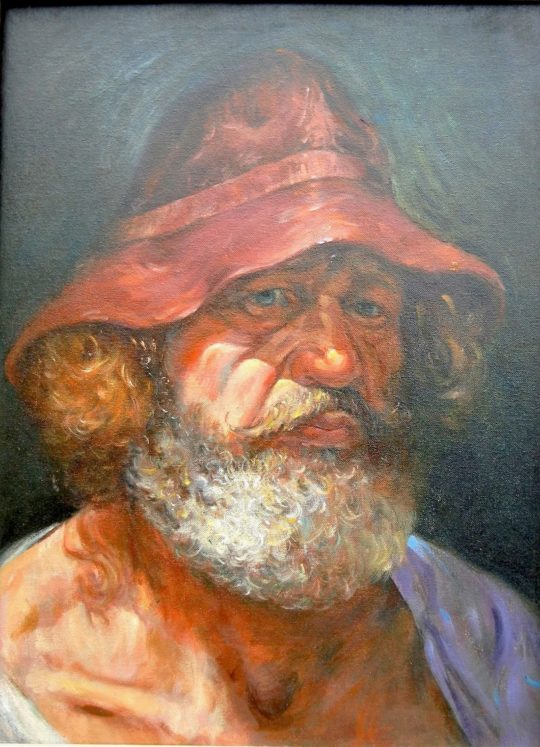

DETAILSSelf-portrait in Red Hat, 1990

18 x 23 inches (45.72 x 58.42 cm) -

DETAILS

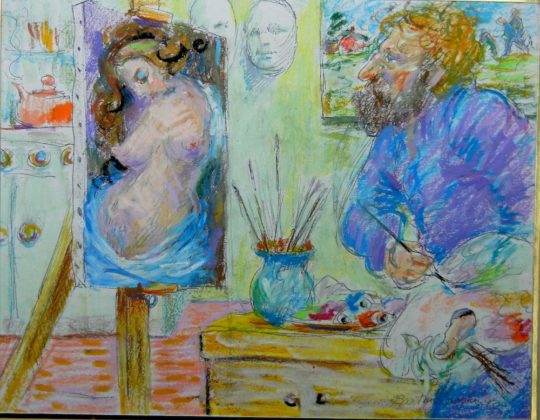

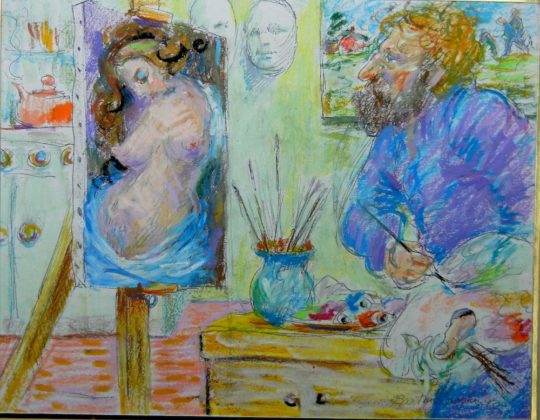

DETAILSSelf-portrait painting a Nude, 1992

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

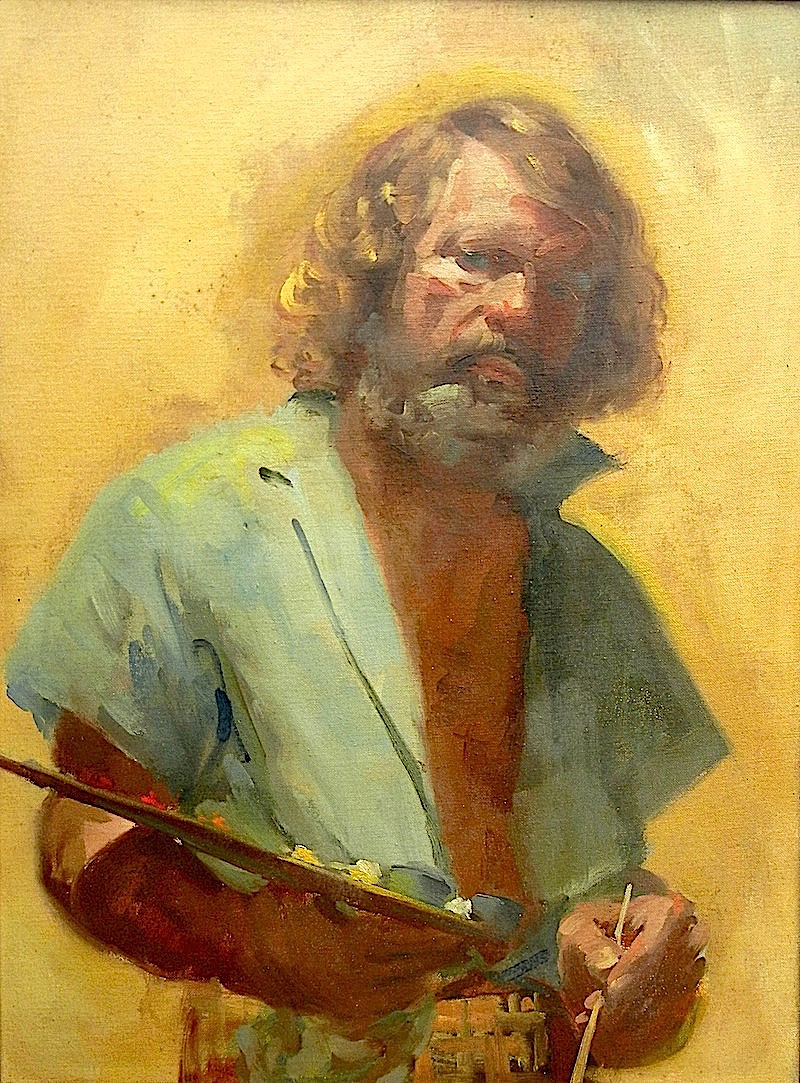

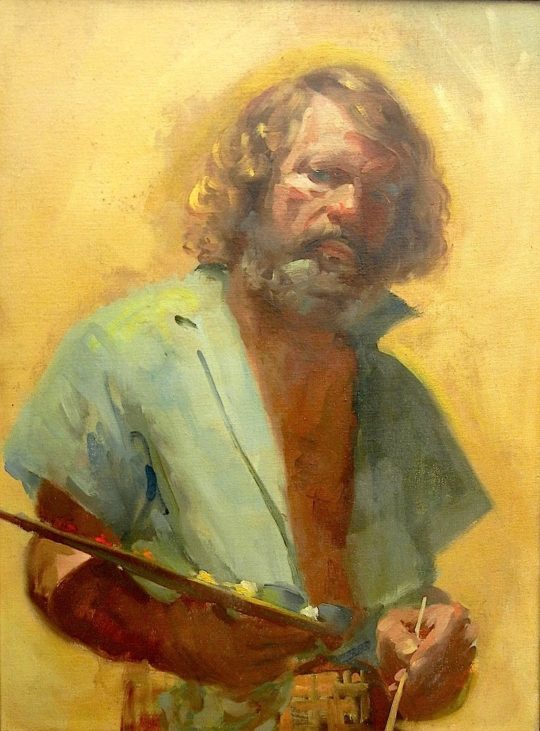

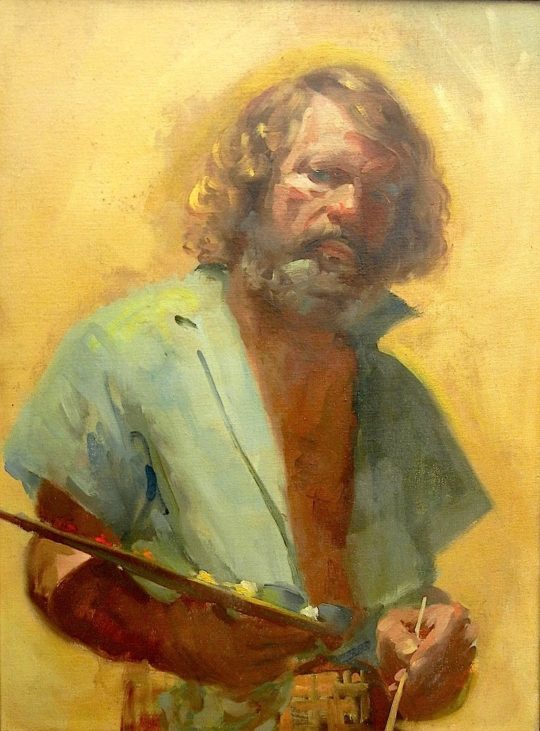

DETAILSSelf-portrait with Palette, 1987

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

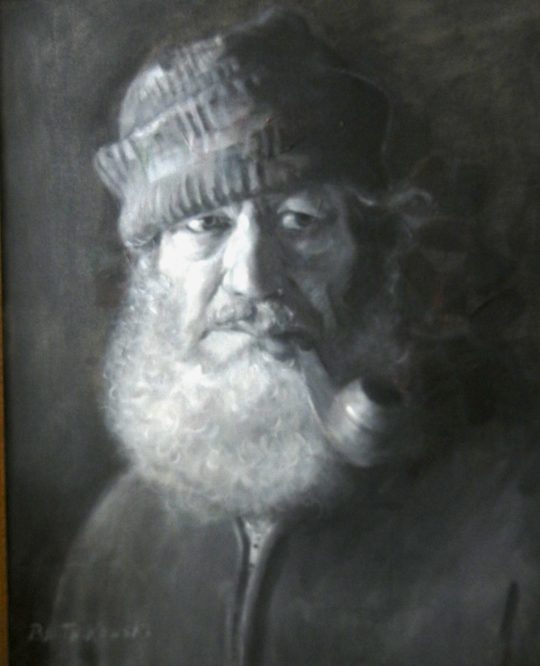

DETAILSSelf-portrait with Pipe, 1990

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSidewalk Market, Brooklyn, 1980

10 x 12 inches (25.4 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSidewalk market, Manhattan Avenue, Greenpoint, 1981

10 x 9 inches (25.4 x 22.86 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSidewalk Scene, Brooklyn, 1987

8 x 10 inches (20.32 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStreet Corner, Brooklyn, 1990

24 x 30 inches (60.96 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Conductor, Brooklyn, 1970

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

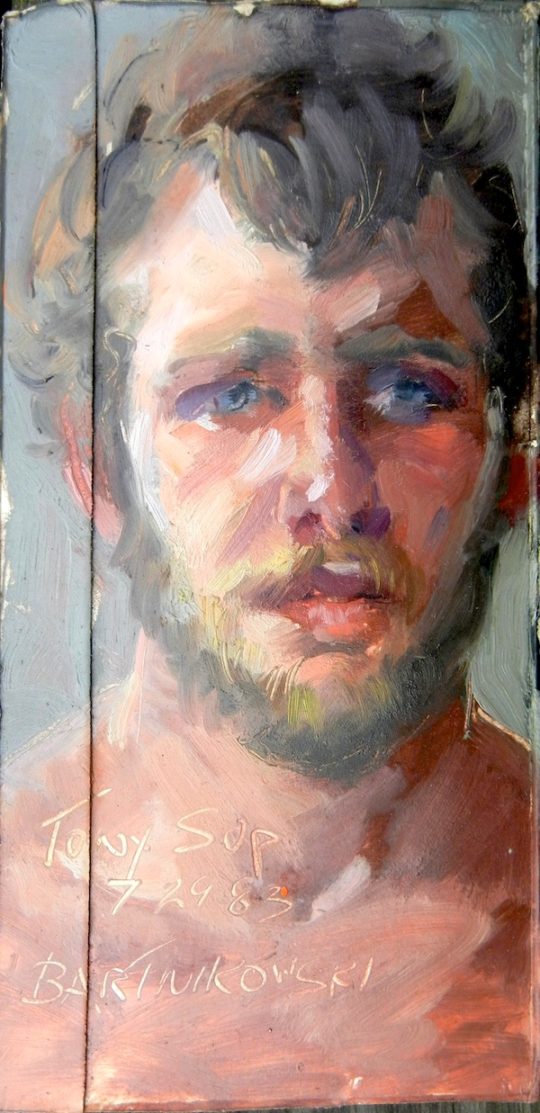

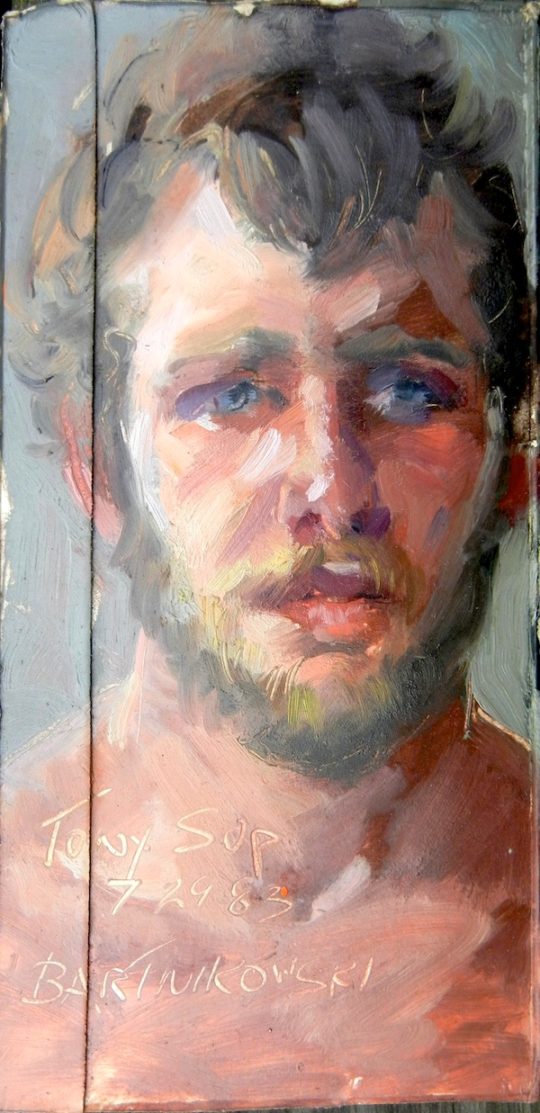

DETAILSTony Sup, 1983

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTraffic, Brooklyn, 1979

9 x 7 inches (22.86 x 17.78 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTrumpet and Sax, 2000

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTrumpet Player in Café, 2000

8 x 10 inches (20.32 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTrumpet, Sax, and Piano, 2000

9.5 x 12.5 inches (24.13 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnder the Umbrellas in the Hamptons, 1995

12 x 10 inches (30.48 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWashington Square, Manhattan, 1987

10 x 7.5 inches (25.4 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWoman with Blue Eyes, 2002

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

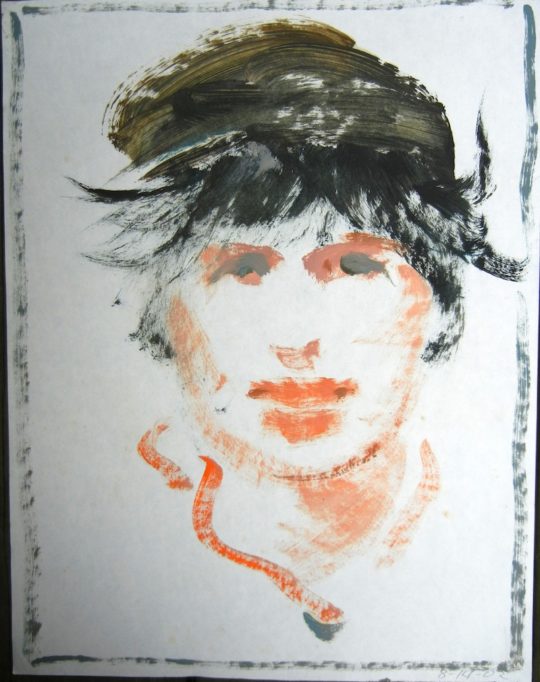

DETAILSWoman with Wispy Black Hair, 2002

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm)

-

DETAILS

DETAILSA Garage under Snow, 1982

7.5 x 3.5 inches (19.05 x 8.89 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSA Lane at the Hospital in Summer, 1975

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSAlex, 1982

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlack Pickup, 1979

9.5 x 8.5 inches (24.13 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBlonde-haired Woman, 1978

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSBrooklyn Street Scene, 1984

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEast Islip Beach, 1990

9.5 x 7.5 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSEast Islip Beach, 1999

7.5 x 3.5 inches (19.05 x 8.89 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSGreenpoint Avenue, Brooklyn, 1978

10 x 8.5 inches (25.4 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMan with Hat, 2001

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMan with Umbrella, 1994

9.5 x 11.5 inches (24.13 x 29.21 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSManhattan Avenue, Brooklyn, 1979

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMarketplace, Brooklyn, 1980

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSMezzarole Avenue, Brooklyn, 1979

9.5 x 7.5 inches (24.13 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (in bedroom), 1996

7.5 x 10 inches (19.05 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (on stool), 1968

9 x 12 inches (22.86 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (profile torso), 2004

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (profile torso), 1968

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (reclining), 1968

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (standing frontal), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (standing frontal), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (standing frontal), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (standing posterior), 1994

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSNude (torso), 1983

3.5 x 5 inches (8.89 x 12.7 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOn the Hospital Grounds in Summer, 1975

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSOutbuildings in Snow, February, 1978

10 x 8 inches (25.4 x 20.32 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPark Entrance, Brooklyn, 1988

30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 1294, 1999

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 301, 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 549, 1990

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 563, 1999

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 581, 1985

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 689, 2001

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 717, 1999

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 784, 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page 828 (Pianist), 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page: 1198, 1999

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPhonebook Page: Pianist, 2001

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPool Players in a Brooklyn Bar, 1980

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSPortrait of a Young Man Screaming, 1985

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSRabbi, 2000

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSRalph, 1984

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait, 1987

10 x 11.5 inches (25.4 x 29.21 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait (as Leonardo da Vinci), 1990

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait at 31, 1957

9.5 x 12.5 inches (24.13 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

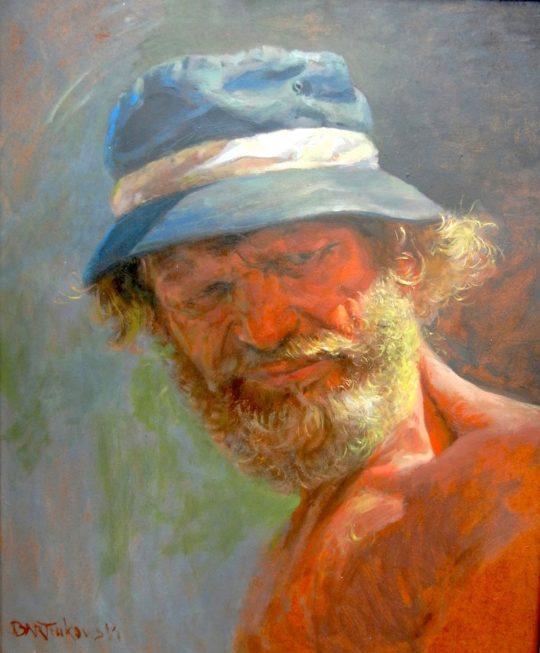

DETAILSSelf-portrait in Blue Hat, 1980

20 x 24 inches (50.8 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait in Hat, 1978

14 x 18 inches (35.56 x 45.72 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait in Red Hat, 1990

18 x 23 inches (45.72 x 58.42 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait painting a Nude, 1992

11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait with Palette, 1987

18 x 24 inches (45.72 x 60.96 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSelf-portrait with Pipe, 1990

16 x 20 inches (40.64 x 50.8 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSidewalk Market, Brooklyn, 1980

10 x 12 inches (25.4 x 30.48 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSidewalk market, Manhattan Avenue, Greenpoint, 1981

10 x 9 inches (25.4 x 22.86 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSSidewalk Scene, Brooklyn, 1987

8 x 10 inches (20.32 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSStreet Corner, Brooklyn, 1990

24 x 30 inches (60.96 x 76.2 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSThe Conductor, Brooklyn, 1970

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTony Sup, 1983

3.5 x 7.5 inches (8.89 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTraffic, Brooklyn, 1979

9 x 7 inches (22.86 x 17.78 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTrumpet and Sax, 2000

9 x 11 inches (22.86 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTrumpet Player in Café, 2000

8 x 10 inches (20.32 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSTrumpet, Sax, and Piano, 2000

9.5 x 12.5 inches (24.13 x 31.75 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSUnder the Umbrellas in the Hamptons, 1995

12 x 10 inches (30.48 x 25.4 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWashington Square, Manhattan, 1987

10 x 7.5 inches (25.4 x 19.05 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWoman with Blue Eyes, 2002

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm) -

DETAILS

DETAILSWoman with Wispy Black Hair, 2002

8.5 x 11 inches (21.59 x 27.94 cm)

No Press releases found.

No News found.

No Events Found.